Discover Seoul Urbanism on TBS eFM's Koreascape

Seoul Urbanism on TBS eFM's Koreascape

Seoul Urbanism on TBS eFM's Koreascape

Author: Colin Marshall

Subscribed: 24Played: 154Subscribe

Share

© All rights reserved

Description

Every month, writer on cities and culture Colin Marshall joins Koreascape host Kurt Achin for an exploration of Seoul's urbanism: its architecture, its infrastructure, its public spaces, and other elements of the Korean metropolis' built environment.

21 Episodes

Reverse

With the end of Koreascape comes the end of Koreascape's Seoul urbanism segment, and so we look back at all we've covered over the past two years. We also ask what the future holds for some of our past destinations, from the 63 Building to Ikseon-dong to Seoullo 7017 to Sewoon Sangga, and what they say about the likely direction of the city itself. Have a listen and you'll surely gather at least a few ideas for your own urbanistic journeys in Seoul to come.

This month we explore Sewoon Sangga, the concrete megastructure that has survived half a century of change in Seoul and is now the subject of a revitalization effort like no other. Originally commissioned by Seoul mayor Kim Hyon-ok (nicknamed "The Bulldozer") and designed by famed architect Kim Swoo-Geun (known for works like the Olympic Stadium, the SPACE Building, and the Freedom Hall), Sewoon Sangga opened in 1968 as Korea's first large development mixing both commercial and residential space. Now, with the eight original buildings reduced to seven and much of the business for its electronics shops lost to other parts of the city — but plenty of activity still going on in its labyrinthine interior and on it wraparound public decks — the Dashi Seun (or "built again") project is rethinking, remodeling, and augmenting Sewoon Sangga for the 21st century in an effort to bring together the expertise of the older generation already there with the enthusiasm of the younger generation of "makers" only just discovering the place.

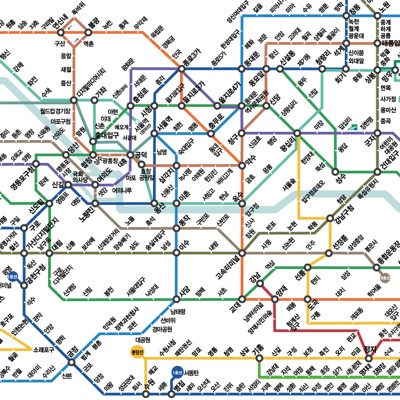

We talk to Nikola Medimorec, co creator-with Andy Tebay of Kojects, an English-language site covering all manner of urban developments in Korea, with a focus on transport and public infrastructure. Nikola has recently got a lot of attention with the aerial photos of Seoul, Busan, and Daegu he has enhanced with the lines of those cities' subway systems. They show all these rail lines not in the abstracted form we've grown used to on standard subway maps, but as they really are, the way they pass through their real geographical environments. Executing the project in Seoul revealed to Nikola a few interesting qualities of the city's urban rail and its prospects for further development.

This month we talk about Seoul's chances of becoming the next great cyberpunk city, following the likes of the future Los Angeles imagined in Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, Chiba City imagined in William Gibson's Neuromancer, and New Port City (or Hong Kong) imagined in Oshii Mamoru's Ghost in the Shell. Expatriate photographers have found much of cyberpunk's "high tech meets low life" sensibility in Seoul's cityscape, especially on rainy nights in the parts of town full of old neon, crumbling alleys, and visible technological infrastructure. We ask what else Seoul needs to achieve proper cyberpunk status, and whether certain other cities in Africa or India might get there first.

This month, as summer begins, we discuss four recommended books about Seoul, three in English and one in Korean: Janghee Lee's “Seoul's Historic Walks in Sketches,” Jieheerah Yun's "Globalizing Seoul: The City's Cultural and Urban Change," SPACE Books' "Beyond Seun-sangga: 16 Ideas To Go Beyond Big Plans," and 오영욱's "그래도 나는 서울이 좋다" (I Like Seoul Anyway). Each of them offers new ways to perceive and consider the city — political, economic, architectural, artistic — and paves the way for other writers to approach Seoul from their own points of view in the future.

This month we walk the Gyeongui Line Forest Park, which cuts across four miles of Seoul on part of the path of the Gyeongui Line train, which back in the colonial period ran all the way to Manchuria. Spared from the high-rise development that now exists immediately alongside it, the area of the Gyeongui Line’s old tracks has become a linear park replete with bike paths, art installations, bookstores, and open spaces for members of the communities through which it passes to complete as they see fit. Beginning just south of Hyochang Park, it ends in the center of the Yeonnam-dong, a neighborhood that has in recent years become hugely popular among young people not least due to the Gyeongui Line Forest Park itself — whose lively Yeonnam-dong section its many young habitués now call “Yeontral Park.”

Having just been to Los Angeles for the first time in the two years since I moved from there to Seoul, I ask what these ever-changing cities can learn from one another. How much does Los Angeles remain a metropolis that "makes nonsense of history and breaks all the rules," in the words of architectural historian Reyner Banham, and to what extent has it moved past what Los Angeles Times architectural critic Christopher Hawthorne calls the "building blocks" of its postwar self, "the private car, the freeway, the single-family house, and the lawn"? Does Seoul's constant construction of more and denser — but blander — forms of housing offer a solution to Los Angeles' worsening cost-of-living (and, increasingly, homelessness) crisis? Can both cities meet their separate challenges of finding a built form and aesthetic commensurate with their formidable status in the 21st century?

With Kurt on vacation, I talk to Na Seung-yeon about six distinctive characteristics of Seoul’s urban space as a whole, including its high-rise apartment complexes; its short-hop “village buses”; its culture of rooms, or bang (방), purpose-built for singing, watching movies, and playing board games; its outdoor eating and drinking spots known as pojang macha (포장 마차); and more. While each of these have potentially positive and negative kinds of impact on urban life, all of them together make the experience of Seoul feel different than that of any other city.

We ride the brand new Ui-Sinseol Light Rapid Transit (or Ui LRT), Korea’s very first driverless light-rail subway. Running from the center of the city out to Bukhansan on its northeastern edge, the line stops at thirteen stations, many of them designed as gallery spaces to display artwork old and new. None of it has to compete with ads for rider attention since, except for announcements of cultural events, the line doesn’t have any ads. Even these early months of operation have also already seen it equipped with machines where riders can check out and return library books, bowls full of poetry (one poem per person, please), and more.

Building on a piece I wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books Korea Blog, we talk about the development of Seoul as you can see it over sixty years of television commercials. These spots advertise things like Lucky household goods, the 63 Building (subject of our first Seoul urbanism segment), the Kia Pride, the 1988 Summer Olympics, the ill-fated Sampoong Department Store, and the Seoul Cityphone (the predecessor of the kind of cellphone service literally everyone in Seoul seems to have today). They also reveal a culture scrambling to change fast enough to keep up with the economy of a rapidly developing country — and an even more rapidly developing capital.

We visit the very first Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, a months-spanning celebration and an exploration of how cities across the world have found innovative ways to use, preserve, and improve their urban and natural “commons.” At one of the Biennale’s main exhibitions at the Dongdaemun Design Plaza, we learn from more than fifty different world cities — Rome with its historical cultural spaces, Bangkok with its street food, Reykjavik with its hot tubs, and even Pyongyang, by a replica of one of its high-rise apartments — what Seoul could incorporate into the next phase of its history.

We go just south of the Han River for a nighttime journey — punctuated by cats, coffee, ukulele riffs, tap dancing, and showers of sparks — through Mullae-dong. There an established generation of industrial operations now coexist with a new generation of cultural venues, putting metalworkers and craftsmen right alongside artists and baristas. We’re joined by Yolanta Siu, whose recent piece “Collective Dust” in Places Journal warns that “the situation in Mullae now calls for artists and factory owners to unite in resistance to speculative capitalism. Otherwise the neighborhood will follow the model of Daehangno, Bukchon, Seochon, Garosu-gil, and Jogno in becoming a generic shopping district,” whose popularity led to rising rents that brought about “not prosperity but hollowness.”

We talk about my recent Guardian article on the branding of Seoul and the city’s efforts to resolve its ongoing identity crisis: hiring place-branding consultants, importing foreign architectural prestige, launching high-profile urban regeneration projects, putting up posters that encourage Seoulites to feel good about their city, introducing slogans like “I.Seoul.U,” and even more besides.

We make the journey to Yongma Land, a long-abandoned neighborhood amusement park in eastern Seoul that has recently drawn such crowds as couples on dates, engagement photographers, Instagrammers, and no small number of music videos and television drama shoots. But though it has become beloved again, the question remains: who abandoned Yongma Land, letting all its attractions — its rideable space ships and squids, its Madonna and Bruce Springsteen portrait-adorned disco ppang ppang, its much-photographed merry-go-round — all go to seed? We dig into the park’s conflicting but always fascinating histories, even sitting down with the facility’s current owner to get his idea of how long Yongma Land has lasted this way, and can last this way, in a development-obsessed city like Seoul.

We pay a visit to the well-known institution of the Noryangjin fish market — or rather, to both of them. After beginning near downtown Seoul in the early 1920s, Noryangjin moved in the early 1970s into a larger concrete complex just south of the Han River, and there became both a thriving commercial center as well as a popular tourist spot. In more recent years, as the old structure has shown its age, a government body built a shiny new building, albeit a more expensive one, for Noryangjin’s many fish merchants to move into, but not all of them have done so — and not all have wanted to. We ask those who’ve moved why they’ve moved, ask those who’ve stayed why they’ve stayed, and make sure to get one of them to slice up a fish right before our eyes (and for our enjoyable consumption).

We get up above Seoul Station and onto quite possibly the city’s most anticipated urban development of the decade: Seoullo 7017. Previously known as the Seoul Skygarden, the project has permanently shut down a freeway overpass and turned it into a walkway park featuring not just a variety of Korea’s plants and trees, but snack shops, foot baths, trampolines, and more besides. Given its repurposing of elevated space for cars as elevated space for people, some have called it Seoul’s own version of New York’s High Line, but the two projects have their differences as well. We talk about them as we walk Seoullo 7017, which opens to the public on May 20th, and also about the challenges of building such a space, the hopes for its future as it settles into a sometimes neglected part of Seoul’s urban landscape, and how it could show freeway-filled Western cities the way forward.

We join urban explorer Jon Dunbar of Daehanmindecline for a walk through an old neighborhood called Bamgol Village — or what’s left of it. Urban redevelopment never stops in Seoul, and when it happens it scrapes whole communities off the map, usually in order to replace clusters of low-rise buildings with another set of the high-rise tower blocks that have increasingly characterized the city since the 1970s. Bamgol Village’s bid to save itself with by filling its walls with colorful murals didn’t pan out, and as in all such condemned neighborhoods, some residents haven’t had an easy time leaving: amid the heaps of rubble stand half-demolished houses still strewn with possessions, and at least one may even remain occupied.

We head down into the Euljiro Underground Shopping Center, a nearly two-mile-long subterranean street running beneath downtown from the City Hall to the Dongdaemun History and Culture Park Line 2 subway stations. Initially opening for business in 1983 at the same time Line 2 itself did, its ever-changing selection of shops supply everything from tailored clothing to computer equipment to medical supplies to punch clocks to electronic cigarettes to freshly baked bread and freshly roasted coffee — not to mention a safe haven from the weather during cold winters like this one. The Euljiro Underground Shopping Center can feel like a part of the city time forgot, but now that it has begun providing space for art installations and hosting exhibits like those of the recent Seoul Architecture Festival, what does its future hold?

We’re joined by German-Korean architect Daniel Tändler of Urban Detail Seoul for a walk through Ikseon-dong Hanok Village, a 1930s-era housing development near downtown that has in recent years seen an influx of restaurants, bars, cafés, shops, and studios putting its traditional Korean residential architecture to whole new uses.

We spend a day riding on Seoul’s buses, which form a transportation network even more impressive, in its way, than the world-class Seoul Metropolitan Subway. We reveal three of the lines that provide the best tours of the cityscape a thousand won or two can buy, point out the kind of attractions you can spot out the windows along the way, break down exactly what the various route colors and numbers mean, take a look at the books written specifically about exploring Seoul by bus, and figure out why buses here don’t carry the American stigma, as Lisa Simpson once put it, of being only “for the poor and very poor alike.”