Discover British Art Talks

British Art Talks

British Art Talks

Author: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art

Subscribed: 51Played: 440Subscribe

Share

© https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode

Description

British Art Talks is the audio series of the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. It features new research and aims to enhance and expand knowledge of British art and architecture.

The PMC is an educational charity that champions new ways of understanding British art history and culture. We publish, teach and carry out research, both at the Centre in London and through our online platforms. Our archives, library and lively events programme are open to researchers, students and the public. The Centre was founded in 1970 by the art collector and philanthropist Paul Mellon. It is part of Yale University and a partner to the Yale Center for British Art.

13 Episodes

Reverse

This series, Experiments in Art Writing, features a set of highly innovative UK-based art writers, asking them to describe the encounters, materials, voices and texts that have shaped the very form of their writing.

Episode image: Bartholomew Dandridge, A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog, c. 1725, oil on canvas, 121.9 x 121.9 cm. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection (B1981.25.205). (Public domain)

This series, Experiments in Art Writing, features a set of highly innovative UK-based art writers, asking them to describe the encounters, materials, voices and texts that have shaped the very form of their writing.

This series, Experiments in Art Writing, features a set of highly innovative UK-based art writers, asking them to describe the encounters, materials, voices and texts that have shaped the very form of their writing.

This programme contains a description of suicide taken from the novel La Fin De Cherí, by Sidonie Gabriel Collette. If you’d prefer to skip over that, it’s between 14:43 - 16:08. If you need support, you can the Samaritans - any time of day or night - on 116 123. Or visit www.samaritans.org.

Episode image: Mattia Preti, Belshazzar’s Feast, 1653-1659, oil on canvas, 202 x 297 cm. Collection National Museum Capodimonte (Q 254). Digital image courtesy of Web Gallery of Art (Public Domain)

This series, Experiments In Art Writing, features a set of highly innovative UK-based art writers, asking them to describe the encounters, materials, voices and texts that have shaped the very form of their writing.

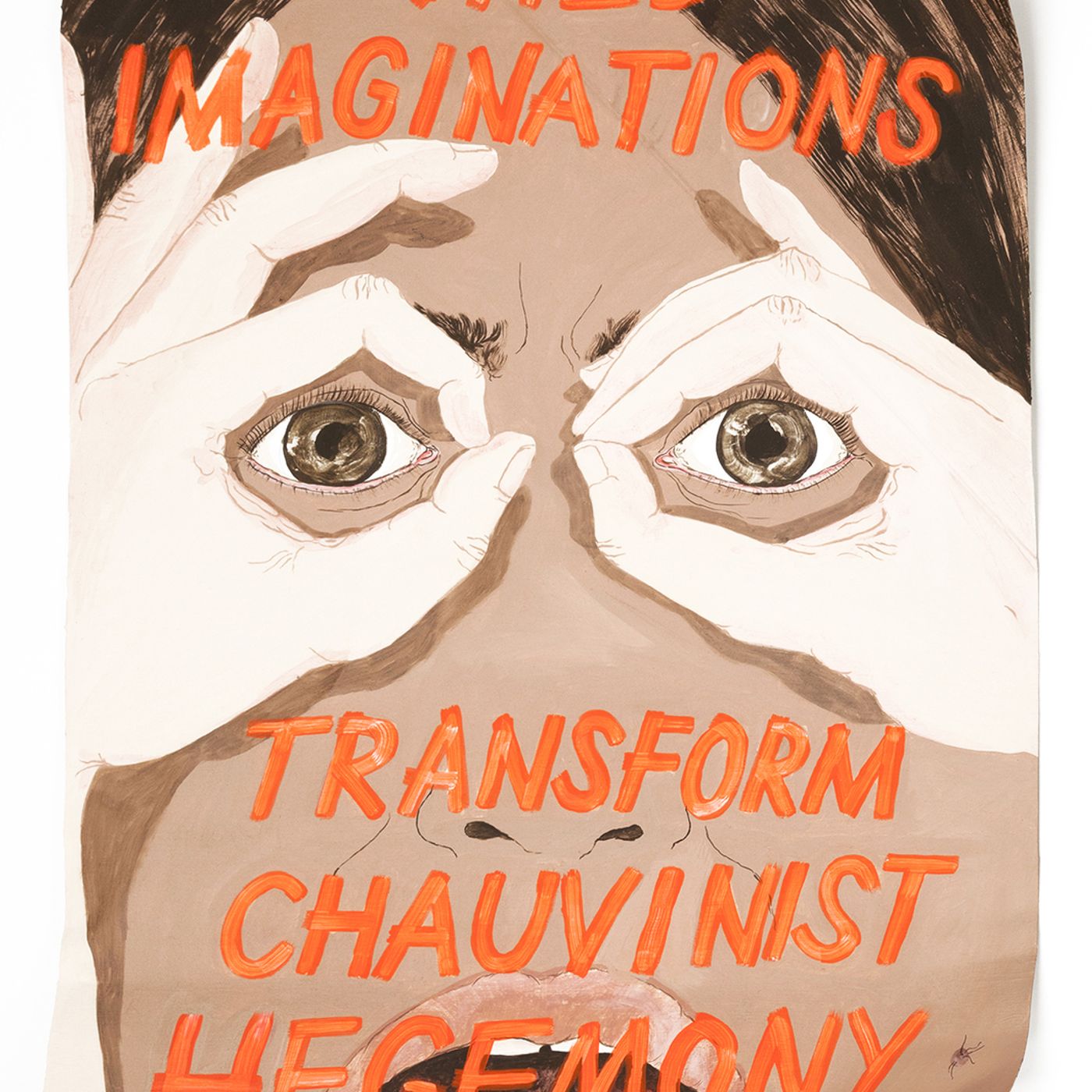

Episode image: Anna Bunting Branch, W.I.T.C.H. ("Wild Imaginations Transform Chauvinist Hegemony"), oil and acrylic paint on folded aluminium sheet, 2016. Courtesy of Anna Bunting Branch.

Ryan Gander’s inventive, shapeshifting and associative works materialise in many forms ranging from sculpture and writing to painting and performance. His engagement with histories is not without mischief, in his 2006 work A Future Lorum Ipsom, Gander invented a palindromic word, ‘Mitim’, designed to be inserted without comment into newspapers, magazines, crosswords or everyday speech, meaning ‘a mythical word newly introduced into history as if it had always been there’. In this episode of British Art Talks, an array of artists is enlisted in a quixotic project: a countdown from fifty in bingo calls. The funny, rhyming calls evoke a history of a game of pure chance, based on random numbers, dating from the early eighteenth century in Britain. They include visual puns and enigmatic idiom. They speak of clandestine activity, village halls and commercial leisure. First, a story, part of a beat poem, narrated by Ryan as author, to his daughter, Penny, in a disarming and semi-autobiographical form: a history of the artist navigating, inventing, transforming, ludic, in time.

Lucy Skaer has exhibited extensively and has had recent solo exhibitions at the Museo Tamayo, Mexico, SMAK, Gent and Kunstwerke, Berlin, and a current solo show at Bloomberg Mithraeum, London. She was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2009 and was awarded the Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award in 2016. She works in collaboration with as Nashashibi / Skaer, and they were included in the last Documenta together. Born in 1975 in Cambridge, she lives and works in Glasgow.

This series foregrounds three contemporary artists, touching on the highly distinctive and unexpected ways in which they both construe and work with histories of their field.

“One could say that I change objects as my work. I recently came to realise that nearly all the forms that I use are pre-existing or borrowed from another artist or object, and my action is to morph the way they act or are understood. In some ways, the house became a transmutation even before my work began: my father had been living there alone for 20 years, during which time he had begun to lose his memory. The house went from a swarming family home to a silent bachelor pad to something altogether more strange as my father’s dementia set in.

The house is deeply familiar to me: filled with books, paintings, prints, ceramics and furniture that formed my first cultural experiences. So, in some ways, the house and the way that my father altered it resemble tactics that I use in my own practice. As my father’s memory detached from the objects that surrounded him, the house became more and more of an abstraction. And this is the way that I re-entered it.”

The garden has long been an important subject matter of the British history of art, but what of the medicinal garden, its visual culture and aesthetics, its significance as a sensory and experimental site, and for artists? This episode brings together a set of scholars whose diverse researches shed new light on the physic, botanical and medicinal garden from the medieval to the eighteenth century. A wide-ranging discussion will consider the relationship between the garden and health, engagements between science and design in the garden, and the visual / literary culture of the medicinal garden.

When John, 13th Duke of Bedford, opened up Woburn Abbey to the paying public in 1955, he took care to maintain the sense that this was his family’s home, even though they occupied only a section of the house, away from the tourist route. As he recorded, his wife, Lydia, ‘succeeded most cleverly in arranging the main state-rooms for show while still making them look as if they were lived in’. To see great treasures such as the Armada portrait of Elizabeth I, the Sèvres dinner service gifted by Louis XV, or the family’s famed Canalettos ‘in their natural surroundings’ was, the Duke averred, much preferable to seeing them ‘displayed along with rows of others in some impersonal museum'.

This paper will sketch out the emergence of this now very familiar trope of the country house as ‘family home’ (whether actual, past or imagined) as an ideal setting for works of art, preferable to ‘some impersonal museum’. It will look at its history from the National Trust country house scheme of the 1930s, through the stately home business of the 1950s, to more recent presentations, as a cornerstone of the case for continued private ownership developed into a fully fledged marketing tool. It will consider the work that this concept has done, both for owners and visitors, and its role in country house presentation today.

Lisa Tickner, a leading historian of British art, has just published a new book on the dynamic art world that emerged in 1960s London. In this podcast, she talks with Mark Hallett about the remarkable array of artists, curators, galleries, art-schools, films, publications and documentaries focused on in the course of her research, and about the highly original way she has written her book

This talk focuses on a key instance of the social realism that played an important role in late Victorian art and culture. Hubert von Herkomer’s Hard Times (1885), has to do with conditions of migrant and insecure labour at the time. Artistically, and in its address to vital social issues, it is an intriguing and complex creation. It continues to strike a chord nowadays, partly because its conception has a certain bearing on present day concerns. Our concerns, though clearly very different from those governing work such as Herkomer’s, have not entirely left behind, or succeeded in radically modernizing, the Victorian conditions this work visualised, and which key figures at the time, most notably Karl Marx, subjected to such powerful critique. At the same time, the ambitions and representational configurations of the late nineteenth-century realist painting of modern life continue to inform much of the art work that examines the fabric of the modern world’s social environments.

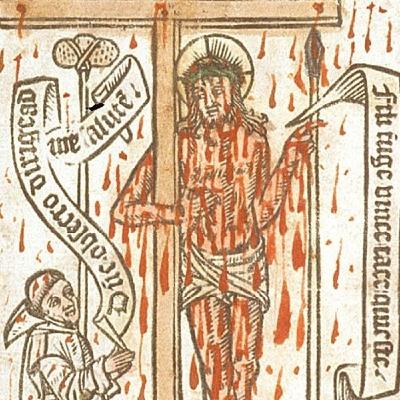

The Carthusian order was founded in the late eleventh century in France. It spread rapidly and widely, and experienced great popularity during the later Middle Ages, when dozens of new charterhouses were founded against a background of sharp decline in monastic foundation in general. The main reason for Carthusian popularity was the order’s consistent adherence to the eremitic precepts and form of living established by its founding fathers. Manifest holiness generated a powerful reputation and patronage to match. The Carthusians also proved adaptable, managing to integrate into urban environments from the thirteenth century onwards without seriously compromising their principles.

This talk covers the art and architectural dimensions of Carthusian life with particular reference to the ten foundations of the order’s English Province. While these monasteries are all largely destroyed, enough survives to give a clear picture of the distinctive layout and elevation of their essential buildings and the sorts of embellishment they received. A fairy large number of Carthusian books and documents has also come down to us, some containing illumination, drawings and seals. Examples of this material that illustrate Carthusian ritual, customs and spirituality will be selected for discussion.

Medieval tombs often depict husband and wife lying hand-in-hand, immortalised in elegantly carved stone: what Philip Larkin would later describe in his celebrated poem, An Arundel Tomb, as their ‘stone fidelity’.

These gestural monuments seem to belong to a broader tendency towards ‘expressivity’ in late-medieval sculpture. Whereas the figures on Romanesque portals stare back at the viewer impassively, their Gothic counterparts beam with radiant smiles, wipe away bitter tears or grimace and gurney with uncontrolled rage. The nature and significance of this shift has been much debated in recent years, in particular the extent to which the heightened representation of emotion was designed to provoke an equivalent emotional response.

This talk explores these ideas through the gesture of joined hands on medieval tomb monuments. I first address the issue of why hand-joining tombs are almost entirely restricted to a fifty-year period in England, before going on to place these amorous effigies in dialogue with wedding rings and dresses, changes to matrimonial ritual, and the new economic opportunities offered to widows. What emerges is the careful artifice beneath their seductive emotional surfaces: the artistic, religious, political and legal agendas underlying the medieval rhetoric of married love.

William Etty was obsessed with the female form. At the height of his career as a history painter, long after his election to Royal Academician in 1828, he sat side-by-side with novices to study naked models, a practice he continued even as his health faded toward the end of his life. Whether posed alone or in groups, these models served as templates for goddesses, graces, muses, nymphs and sirens in his finished paintings. Bypassing the conventions of his day, Etty abandoned the doctrine that the figure ought to be idealised according to the established norm of beauty based on Greco-Roman sculpture. His nudes tend to have breasts, thighs and other bodily features that are larger or more irregular than had long been customary. As the audience for contemporary British art grew steadily throughout his lifetime, his flouting of convention proved exciting and scandalous.

But there is more to Etty’s art than a move to a more naturalistic or realistic aesthetic. In his works, the female body remains mysterious and opaque, layered in flesh and rich paintwork. Many of the women who posed for him were employed simultaneously as sex workers, a fact that created a palpable sense of tension in the critical reception of his achievements, and arguably within the paintings themselves. This programme will take a look at this endlessly fascinating artist, exploring the conspicuous sensuality of his take on the classical body.