Discover Subtext: Conversations about Classic Books and Films

Subtext: Conversations about Classic Books and Films

Subtext: Conversations about Classic Books and Films

Author: Wes Alwan and Erin O'Luanaigh

Subscribed: 290Played: 10,435Subscribe

Share

Copyright © 2020-2024 | (sub)Text | All Rights Reserved

Description

Subtext is a book club podcast for readers interested in what the greatest works of the human imagination say about life’s big questions. Each episode, philosopher Wes Alwan and poet Erin O’Luanaigh conduct a close reading of a text or film and co-write an audio essay about it in real time. It’s literary analysis, but in the best sense: we try not overly stuffy and pedantic, but rather focus on unearthing what’s most compelling about great books and movies, and how it is they can touch our lives in such a significant way.

161 Episodes

Reverse

Wes & Erin continue their discussion of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” and its sustained reflection on how political power is constructed, located, and legitimated.

Upcoming Episodes: “Amadeus,” Susan Sontag’s “On Photography.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

Wes & Erin continue their discussion of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” and its sustained reflection on how political power is constructed, located, and legitimated.

Upcoming Episodes: “Amadeus,” Susan Sontag’s “On Photography.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

Wes & Erin continue their discussion of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” and its sustained reflection on how political power is constructed, located, and legitimated.

Upcoming Episodes: “Amadeus,” Susan Sontag’s “On Photography.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

Wes & Erin continue their discussion of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” and its sustained reflection on how political power is constructed, located, and legitimated.

Upcoming Episodes: “Amadeus,” Susan Sontag’s “On Photography.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

Wes & Erin continue their discussion of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” and its sustained reflection on how political power is constructed, located, and legitimated.

Upcoming Episodes: “Amadeus,” Susan Sontag.

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

Brutus is an honorable man, but Caesar is Caesar: at the beginning of Shakespeare’s play, his name is near the point of becoming synonymous with dictatorial power, and his every wish, as Mark Antony points out, has the substance of a command. For the rebels who oppose him, this identification of political authority with personal will is a perversion of republican institutions, and a form of corruption that justifies any means of putting an end to it, even if that means killing a friend. Yet Brutus’s conception of himself as unflaggingly virtuous is one he in fact shares with Caesar, and perhaps reflects the same authoritarian tendency, in grounding the legitimacy of political action in the character of a particular actor. Then again, it is not clear that democratic institutions will always forestall authoritarian tendencies, rather than enable the masses to sanction absolute power in a charismatic leader. Wes & Erin discuss Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” and its sustained reflection on how political power is constructed, located, and legitimated.

Upcoming Episodes: “Amadeus,” Susan Sontag.

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

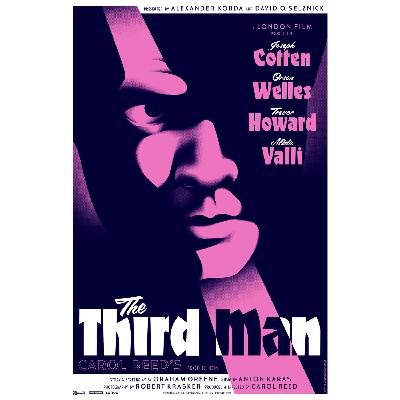

Wes & Erin continue their discussion of the 1949 classic film “The Third Man,” about friendship and betrayal, and about the stories we tell ourselves in order to love, survive, kill, or even die.

Upcoming Episodes: “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

The so-called “third man factor” is a phenomenon in which people in dire circumstances experience the presence of an extra person in their midst who gives comfort and aid when it’s most needed—a guardian angel, perhaps, or some figure of divine intervention. Harry Lime seems to have played just such a role in the lives of Holly Martins and Anna Schmidt. But is Lime from heaven or from hell? Perhaps a less-than-angelic third man might estrange rather than bring together, muddle rather than clarify, adulterate rather than help. And indeed, as a black market middle-man, Lime has the devilish power to intervene in people’s lives for the worse—like a narrator who edits out characters and manipulates the plot. Wes & Erin discuss the 1949 classic film “The Third Man,” about friendship and betrayal, and about the stories we tell ourselves in order to love, survive, kill, or even die.

Upcoming Episodes: “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

Like many of its genre, the film “Elf” connects Christmas spirit to the sorts of bonds that hold together families and communities, despite their inevitable tendencies towards conflict and dissolution. Wes & Erin discuss this 2003 classic, what it means to believe in Christmas, and how this is connected to the possibility of a genuine community.

Upcoming Episodes: “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

Half the plot involves a man reuniting with his father—and his species—after being raised by Christmas elves. The other involves saving Christmas itself from the growing cynicism of humanity. And so like many of its genre, the film “Elf” connects Christmas spirit to the sorts of bonds that hold together families and communities, despite their inevitable tendencies towards conflict and dissolution. Indeed, there’s a sense in which Christmas elves are, in making gifts, hard at work maintaining the social fabric against the forces of individual selfishness. But in this story, the elf in question turns out to be a bumbling man-child—a holy fool of sorts—who helps re-enchant communal life by holding up its social deficits to a naive mirror. Wes & Erin discuss this 2003 classic, what it means to believe in Christmas, and how this is connected to the possibility of a genuine community.

Upcoming Episodes: “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

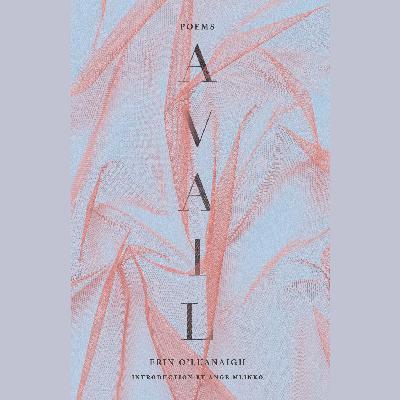

Erin just published her first book, “Avail,” which you can order here: https://www.pauldrybooks.com/products/avail

“Avail” features a long prose-poem which titles the book and winds through sections of lineated, often formal poems. The prose-poem comprises a series of lyric meditations on the image of the veil—from religious and cultural veils, to veils imbedded in idiom and metaphor, to veiled women in art and classic films, to veils drawn and parted by illness and death—which slowly divulge the harrowing details of the poet’s blood disorder.

Throughout, allusions to classic film, literature, and art serve as the “veils” with which the poet attempts to obscure the self-estrangement and vulnerability her illness has induced—insecurities which follow her long after her recovery. In a poem about a break-up set during her career as a jazz singer and against the backdrop of a 1930s screwball comedy, she longs “to shake life by the martini (but stay self- / possessed), to star in the movie of myself / instead of playing second lead.” During a visit to Naples, Mt. Vesuvius becomes “a Crawford eyebrow / arched over the bay.” And in California, after a trip to the Getty Villa, she recalls Sontag’s “missive on allusion, that no part / of any work is new, that all is reproduction.” By the end of the collection, O’Luanaigh has fashioned from the sum of these various allusions her own poetic identity, unveiled in the poems themselves.

Upcoming Episodes: “The Third Man,” “Elf,” “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

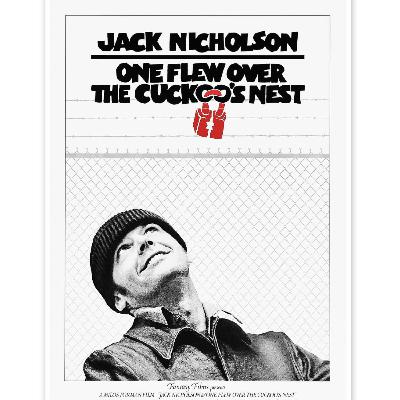

What happens when the Godzilla of superegos takes on a libidinal King Kong? Wes & Erin continue their discussion of the 1975 film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

Upcoming Episodes: Erin’s book “Avail,” “The Third Man,” “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

Nurse Ratched likes a rigged game, according to R.P. McMurphy. And it’s true that the game he is playing—lawless and hedonistic, but also vital and free-spirited—is unwinnable on her sandlot. As their conflict develops, we seem to be asked to compare the therapeutic value of McMurphy’s introduction of the Dionysian, to Ratched’s attempt to enforce an ordered calm within the psychiatric ward over which she is absolute ruler. What happens when the Godzilla of superegos takes on a libidinal King Kong? Wes & Erin discuss the 1975 film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

Upcoming Episodes: Erin’s book “Avail,” “The Third Man,” “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

What’s the difference between collaborating with Nature and mining her secrets? Where is the line between imitation and interpretation? And can love only work its magic through the creative, rather than the critical, faculty? Wes & Erin continue their discussion of two short stories by Nathaniel Hawthorne: “The Birth-Mark” and “Drowne’s Wooden Image.”

Upcoming Episodes: “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

The short stories we cover in this episode pit the magic of art against that of scientific discovery. In one story, a woodcarver transcends his materials and his own humble talents to create a sculpture that bears an otherworldly resemblance to a real woman. In the other, a scientist uses his estimable but flawed powers to improve on Nature’s design by removing a birthmark from his wife’s otherwise-perfect face. The varying results of these efforts seem to correspond to the extent with which love, that most magical of forces, underscores them. “You cannot love what shocks you,” the scientist’s wife remarks when her husband expresses how disturbed he is by her imperfection. What’s the difference between collaborating with Nature and mining her secrets? Where is the line between imitation and interpretation? And can love only work its magic through the creative, rather than the critical, faculty? Wes & Erin discuss two short stories by Nathaniel Hawthorne: “The Birth-Mark” and “Drowne’s Wooden Image.”

Upcoming Episodes: “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

What is a gift without control or discipline, a skill without purpose or meaning? And is there a difference between a gift and luck? Wes & Erin continue their discussion of Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 film “There Will Be Blood.”

Upcoming Episodes: Hawthorne’s “The Birth-Mark” and “Drowne’s Wooden Image,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

The clash between Eli Sunday and Daniel Plainview, between religion and industry, steeple and oil derrick, might come down to something like the difference between a gift and a skill. Eli calls himself a son of the hills of Little Boston, an inheritor of land and legacy, a member of a family, and of a faith imagined as a family. Daniel calls himself an oil man, but only after reciting his resume as proof that he’s earned the title. He tends flocks of derricks, not people, and he leases both land and family to strategic, rather than communal, ends. Yet ultimately, each lacks what the other has. What is a gift without control or discipline, a skill without purpose or meaning? And is there a difference between a gift and luck? Wes & Erin discuss Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 film “There Will Be Blood.”

Upcoming Episodes: Hawthorne’s “The Birth-Mark” and “Drowne’s Wooden Image,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Julius Caesar.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

In Ibsen’s “An Enemy of the People,” two conceptions of communal health do battle. Dr. Stockmann’s is progressive, focused as it is on the vitality of the young, their new ideas, and the possibility of growth into a better future, even if that means encroaching on the powers that be. His brother’s is conservative, focused on the use of authority and ascetic self-restraint to preserve existing achievements and ideas. But once in conflict, these conceptions seem to reveal themselves to be competing forms of elitism, and expressions of contempt respectively for both past and future. Wes & Erin discuss whether there is a more nuanced conception of the common good available to us, and how it might be related to the sudden turn at the end of the play to the the role of education.

Upcoming Episodes: “There Will Be Blood,” “Julius Caesar,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

In Ibsen’s “An Enemy of the People,” two conceptions of communal health do battle. Dr. Stockmann’s is progressive, focused as it is on the vitality of the young, their new ideas, and the possibility of growth into a better future, even if that means encroaching on the powers that be. His brother’s is conservative, focused on the use of authority and ascetic self-restraint to preserve existing achievements and ideas. But once in conflict, these conceptions seem to reveal themselves to be competing forms of elitism, and expressions of contempt respectively for both past and future. Wes & Erin discuss whether there is a more nuanced conception of the common good available to us, and how it might be related to the sudden turn at the end of the play to the the role of education.

Upcoming Episodes: “There Will Be Blood,” “Julius Caesar,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

Pre-order Erin’s forthcoming book “Avail” here: http://subtextpodcast.com/avail

For bonus content, become a paid subscriber at Patreon or directly on the Apple Podcasts app. Patreon subscribers also get early access to ad-free regular episodes.

This podcast is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit AirwaveMedia.com to listen and subscribe to other Airwave shows like Good Job, Brain and Big Picture Science.

Email advertising@airwavemedia.com to enquire about advertising on the podcast.

Follow: Twitter | Facebook | Website

Listen to more episodes of (post)script at Patreon.

Wes & Erin continue their discussion of “The Great Gatsby”; the ongoing development of our approach to the discussions; Arnold Rothstein and the fixing of the 1919 World Series; Fitzgerald’s neighbors on Long Island, including Ring Lardner and Ed Wynn; the contemporary feel of the novel; the NYC movie-making scene in the early 20th century; Marilynne Robinson; and possibilities for the next episode, where because of a weird time warp we talk as if “A Woman Under the Influence” will follow “The Great Gatsby” when it has always already preceded it.

I love this program but was disappointed in parts of this analysis of Chinatown. Two examples. Regarding the old gardner, his accent and expertise indicate he was Japanese, not Chinese. I didn't get that Jake Gittes held contempt for the old man, just that he misunderstood him. Erin's disapproval of Gittes and expectation that he should hold the progressive values of a modern academic is misplaced and a form of presentism. Gittes is a character, accurate for his time, place, and class but not despicable for his blind spots but more interesting to the viewer.

wonderful. They really get to the heart of the art they explore and make a wonderful case for why we should all delve into canonical works.

excellent podcast.

great movie, great discussion.

5+Starts. Excellent podcast especially for people who like to go beyond surface level meaning in movies, poems and novels. Big admirer of Wes from PEL and Erin is great host with insightful details. Highly recommended

5 STARS. They have intelligent things to say about the possible meanings and interpretations of texts. Deeper and more personable than most such podcasts. Most crucial is that both their voices are soothing and resonant.