Discover The Natural Curiosity Project

The Natural Curiosity Project

The Natural Curiosity Project

Author: Dr. Steven Shepard

Subscribed: 18Played: 475Subscribe

Share

© All rights reserved

Description

I photograph, record, and write about the natural world. I see, I listen, I write. I fundamentally believe that curiosity can save the world—so I publish stories to make people curious. Ultimately, curiosity leads to discovery, discovery leads to knowledge, knowledge leads to insight, and insight leads to understanding. Please enjoy!

333 Episodes

Reverse

Weird, isn't it, that wind is completely silent--silent, that is, until it hits something. Then, it bursts out in myriad voices.

In this episode we travel from central Turkey, the region known as Anatolia, to northern Norway, on the island of Svalbard, to visit two extraordinary subterranean places.

IT's hard to believe that I have created 300 episodes of the Natural Curiosity Project. Thank you so much--SO much--for staying with me on the adventure. In this episode, Pete Mulvihill recalls some of his favorite episodes--and asks me for mine.

The episodes mentioned in the program are 84 (Bud and the tumbleweeds); 77 (How to Read Movie Credits with Bob Verlaque); 181 (Rob Prince and Dark Winter Nights); 206 (Dewitt Jones); 15 (How Trees Work); 16 (Forest Bathing); and 97, 99 and 109 (Letter-writing). Enjoy!

Acronyms are "words" that are abbreviations. But they differ from abbreviations because they can be pronounced like a word. Many of these acronyms, like the 'ZIP' in 'Zip Code,' aren't even known as acronyms anymore. In this episode, my friend Pete Mulvihill helps me decode some of the most common acronyms in modern lexicon.

Author John Stilgoe exhorts us to go outside, take a walk or a bike ride, and tune in to the world before us that we miss when we whiz by in a car. I implore you to do the same thing--but instead of paying attention to what you see, pay attention to what you hear.

I was listening to music the other day while driving to and from the dump, and one of my favorites came on: Mr. Bojangles, by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. Like most of the songs that rise to the top of my favorites list, Mr. Bojangles has the best qualities of storytelling. But as I listened, I started thinking, something that always gets me in trouble. And, it did. I wanted to know: Who was Mr. Bojangles? Was he real? Well, it turns out that yeah, he was, but there’s a lot more to the story than a single person.

Some additional thoughts on the craft of writing.

Episode 295-The Most Complicated Machine Ever Built by Dr. Steven Shepard

I spent a great deal of my life in Monterey, California, most of it under the water while teaching SCUBA diving. I recently discovered a Monterey story that held me spellbound. It begins like this: A marine biologist, a mythologist, and a novelist walk into a bar...

An homage to Jane Goodall and others like her. This is a repost from 2021.

This essay contains an important story for the ages. Given current events, and the absolute truth that history does repeat, the lesson is plain, and chilling. 1492 and the years leading up to it in Medieval Spain, were times that should not be repeated. And yet…

Sometimes, curiosity, awe and wonder are the only tools we have. But when it comes to the majesty and magnitude of the night sky, of all the things about it we can’t possibly comprehend, they’re actually the best tools we can have. In this episode we talk about the magic and wonder that happens late at night, when it’d just you, the sky, and pure awe.

I recently had a conversation about technology’s impact on research today. It’s an argument I could make myself—that technology has resulted in access to more data and information. For example, before the invention of moveable type and the printing press, the only books that were available were chained to reading tables in Europe’s great cathedrals—they were that rare and that valuable.

BUT: Does technology give me access to BETTER data and information? I believe the answer to that is no, for a very specific reason: It leaves out the all-important human element in the knowledge molecule, the element that makes sense of the data and then converts it to information. Have a listen.

It’s human nature for each generation to criticize the generation that preceded it, often using them as a convenient scapegoat for all that’s wrong in the world. The current large target is my own generation, the Baby Boomers. I recently overheard a group of young people—mid-20s—complaining at length about their belief that the Boomers constitute a waste of flesh who never contributed much to society. Respectfully, I beg to differ; this is my response, along with a plea to ALL generations to think twice about that conclusion.

Musings on science, philosophy, and the limits of human knowledge.

Short and Sweet: A challenge to our government and our politicians--all of them--to do their jobs. In good conscience, I can't NOT post this audio essay.

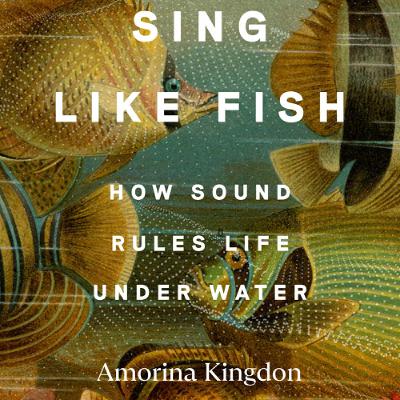

I read something the other day that had a reference in it to a new book that had just come out. The book’s called, “Sing Like Fish,” and it’s written by author and science writer Amorina Kingdon. Needless to say, I immediately ordered the book, and I have to tell you, I burned through it in three days. The subtitle is, “How Sound Rules Life Underwater,” which you can imagine, as a wildlife sound recordist, really caught my attention.

Actually, a few things in the book caught my attention, including this quote:

“For all the wonders and worries of this subject, the truth is that noise does not match the deep threat posed to the oceans by climate change. And yet, neither issue is monolithic or exists in a vacuum. Warming or acidifying waters will conduct sound differently: Sound’s effect on ecosystems like reefs or Arctic food webs will ricochet into animals’ responses to climate change.

Yet I believe that it is never a waste to examine the world though a new lens, through a new sense.”

That’s powerful writing. So, as I tend to do, I went looking for the author, and I found her north of the border in British Columbia. Amorina and I had a nice chat, discovered that we have a lot of common interests, including, of all things, the acoustic work done by Bell Laboratories, and she agreed to be on the program. Our conversation wandered all over the landscape—I recorded more than three hours of tape—but I edited it down to the most important points. Here's Amorina.

On a warm fall day in eastern Nebraska, I met up with wildlife biologist Bethany Ostrom of the Crane Trust. As we talked, we took a long walk along the banks of the Platte River, watching as small grasshoppers by the hundreds boiled out from under our feet like popcorn, listening to meadowlarks and bobolinks calling from the scrubby brush along the river.

The Crane Trust monitors the health and welfare of North America’s population of both migratory sandhill cranes, which number in the hundreds of thousands, as well as the highly endangered whooping cranes, which number less than a thousand in the entire migratory population.

The health of the crane population is a bellwether for other species, and underlines the importance of the work done by Bethany and her colleagues.

Imagine a place right here on Earth—not on Mercury or Venus—where it’s not particularly unusual for the summer temperature to soar to 180 degrees Fahrenheit (82 degrees C). Now imagine a 20-meter or 60-foot-tall building in that hellish place where ice can be safely stored, completely frozen, for the entire summer. Oh—I should also add that the building has no electricity and is made out of mud, goat hair, ash, and egg whites.

These buildings exist, and they’re called Yakhchals. They’re found in the Middle East, mostly in Iran, in places where it gets very cold in the winter, when ice can be made, and very hot in the summer. They’re a type of evaporative cooler—in the dry parts of the American south, a similar technology is called a swamp cooler—and these Yakhchals been in continuous use since at least the fourth-century BCE.

Every once in a while, an idea hits me that causes one of those stop-the-presses moments, usually caused by some triggering event—in this case, the senseless, ongoing attacks on and defunding of scientific research by a group of decision-makers who aren’t sure if there’s an ‘I’ in the word ‘science.’ They make me think of a line from the movie Armageddon, in which the Air Force general says to Billy Bob Thornton, one of the NASA executives, “You’re asking me to put the future of the planet into the hands of a group of people that I wouldn’t trust with a potato gun.”

The world reveres art, especially music and the artists who create it. The same is true of sports figures. Look at the way we hold up rock musicians and professional athletes as if they were celestial deities, sitting beside Zeus and Apollo and the rest of the pantheon. But when’s the last time we saw such reverence for science and the scientists who strive to understand the ways of the universe? In fact, I know you can name musicians and sports figures. But how many scientists can you name, once you get past Einstein, and maybe Bill Nye and Neil DeGrasse Tyson? It’s time to change that, don’t you think?