Discover Crude Conversations

Crude Conversations

Crude Conversations

Author: crudemag

Subscribed: 19Played: 618Subscribe

Share

© Copyright 2018 All rights reserved.

Description

Each week ”Crude Conversations” features a guest who represents a different aspect of Alaska. Follow along as host Cody Liska takes a contemporary look at what it means to be an Alaskan.

Support and subscribe at www.patreon.com/crudemagazine and www.buymeacoffee.com/crudemagazine

Support and subscribe at www.patreon.com/crudemagazine and www.buymeacoffee.com/crudemagazine

294 Episodes

Reverse

Kevin Lane is the executive chef and co-owner of The Cookery and The Lone Chicharron Taqueria in Seward, and he was recently named as a James Beard Award semifinalist. Reflecting on that recognition, he says it wouldn’t have been possible without his team at The Cookery, or the kitchens and crews from his past that shaped the way he cooks today. Those roots stretch back to California’s Sacramento area, where he was raised on crockpot meals, black-eyed peas, and lentil stew, before he found his way into kitchens in San Diego. Around nineteen, he was eating street tacos, shucking oysters, and learning the pace of restaurant life — first on the cold oyster bar, then on the hotline, where teamwork and discipline took root. Those early experiences still show up in his food today — the steady presence of Mexican influence, the belief that cooking is ultimately about making people happy, and he’s still shucking oysters.

He was still early in his career when he moved to Juneau to work as a Sous Chef. There, and later in Sitka, he recognized the realities of Alaska’s food system, how kitchens relied heavily on frozen and canned goods because they were dependable. Orders had to be placed seven to ten days out, and even then, fresh vegetables and herbs might arrive frozen and mushy. It was a lot different from working in California, where you could order produce in the morning and expect it that afternoon. The learning curve was steep, but learning to adapt is what good cooks do. So, given Alaska’s abundance of fresh seafood, he adjusted his cooking and learned to let fish become the focus. And now that there’s more access to farm-fresh produce than ever before, the constraints that once defined cooking in Alaska have eased, expanding what’s possible on a menu.

In this one, Cody talks to cartoonist Peter Dunlap‑Shohl. His career traces a remarkable arc, from daily newsroom deadlines to personal, long-form storytelling. For 27 years, he worked for the Anchorage Daily News, drawing editorial and political cartoons. He produced thousands of comics focused on, more often than not, the worst things he could find in Alaska politics and in the pages of the newspaper — the biggest screwup, the clearest malfeasance, the loudest troublemaker — and then he’d satirize it by cartooning it. This is how a newspaper cartoonist does their job. But he also worked on the comic strip Muskeg Heights. The strip was about a fictional Anchorage neighborhood, and it allowed him to step out of the editorial page — away from politics — to explore the emotional aspects of living in Alaska. He worked on that for about a decade, until Parkinson’s made it too difficult to keep up with the weekly pace of the work.

In more recent years, he’s authored two graphic memoirs: My Degeneration, about his Parkinson’s diagnosis in 2002, and Nuking Alaska, about the nuclear dangers Alaska faced during the Cold War. Both books were something Peter never thought he’d be capable of creating after being diagnosed. But he says that with the help of medication and brain surgery, he’s been able to curb the effects of the disease and accomplish some of the most rewarding and successful work of his life. But he’s careful not to frame the disease as a gift because it’s not. In My Degeneration, he writes that "it’ll take everything from you, everything it has taken you a lifetime to acquire and learn." What is a gift, though, is his reaction to it — the power of medicine, human ingenuity, and perseverance are incredible things. Overall, it’s taught him that he’s not in control, and that on his best days he’s sharing the wheel with Parkinson’s.

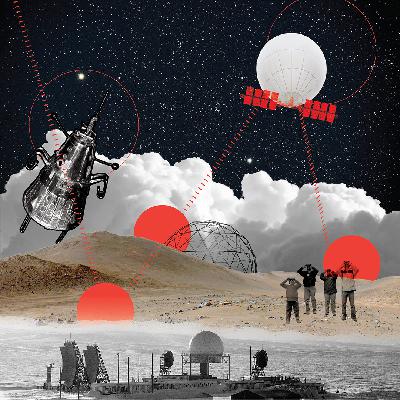

Charles Stankievech is an artist, a writer, and an academic. He teaches at the University of Toronto, and his art takes him into some of the most remote landscapes on earth. Places like CFS Alert, the northernmost permanently inhabited place in the world. He describes the Arctic as occupying two parallel spaces in our cultural imagination: one built on myth and fantasy, and another grounded in harsh, physical reality. He says that most people will never set foot there, which means our understanding of it comes from ideas rooted in medieval tales of magnetic mountains, science-fiction fortresses carved out of ice, or the general sense that it’s a blank, unreachable expanse. But beneath that fantasy is a real landscape shaped by nature and human activity.

One of Charles’ early Arctic projects was about the Distant Early Warning Line, a network of Cold War radar stations built across the Arctic to detect incoming Soviet bombers. He began thinking about how the remnants of that global conflict were already entangled with what he called an emerging “Warm War,” where rising temperatures and melting sea ice would turn buffer zones into contested shipping routes and resource frontiers.

Sound is one of his primary tools for understanding these places. He says that what you hear often tells a different story than what you see, and so his work uses sound to help people experience aspects of a place that visuals alone can’t capture. That instinct connects back to his own life — long days spent alone in the Rockies with his dog, camping, hiking, and snowboarding in the backcountry. Those solitary experiences were a refuge, a place where existential questions emerged naturally. It’s where he learned that when you confront the world on your own terms, you gain a clearer understanding of yourself and the people around you.

Kikkan Randall is a five-time Olympian and an icon of U.S. cross-country skiing. But before all the medals and podiums, she was a high schooler with dyed hair, face paint, and a nickname that captured her energy: “Kikkanimal.” Her teammates gave it to her as a nod to the edge, spirit, and unity she brought to the team. Cross-country skiers understand that it’s a sport that rewards time spent—refining muscle memory, living in a zone of discomfort, and building toward the kind of performance that only shows up after years of hard work. Raised in a family that loved the outdoors, Kikkan found herself drawn to this community of grounded, like-minded people. And as her competitive fire grew, so did her sense of camaraderie—training alongside rivals, and becoming genuine friends with competitors from places like Finland.

When Kikkan crossed the finish line to Olympic gold, it was a breakthrough for American skiing. What once seemed out of reach had become reality. But her team had done more than stand on a podium, they’d changed the culture. They trained together, got to know each other outside of training, and showed up to races in face paint, neon and novelty socks. And in that show of teamwork and connection, they built something so strong that other national teams started to emulate.

That same spirit followed Kikkan beyond sport. After retiring at the top of her game, she faced a breast cancer diagnosis, and her athlete mindset took control. She broke the treatment into pieces, taking it on one small battle at a time. It kept her focused on the day-to-day work rather than the big picture. It’s the same mindset that carried her through five Olympics—one that relies on optimism and patience. Today, she’s back where it all started, leading the Nordic Skiing Association of Anchorage and shaping the future of the sport she helped redefine.

In this one, Cody talks to Alev Kelter. She grew up in Eagle River, Alaska, playing varsity boys' hockey because there wasn’t a girls’ team. That drive to compete at the highest level has carried her through a career that spans multiple sports. She played soccer and hockey at the University of Wisconsin, and was part of U.S. national team programs in both sports—earning spots on the U.S. hockey national teams and joining the national player pool for soccer. After just missing a spot on the U.S. Olympic hockey team in 2014, she pivoted to rugby. She’d never played the game before, but because she was surrounded by a supportive coach and teammates who believed in her and helped her learn, rugby became the next chapter in her story. Now, nearly a decade later, she’s helped lead Team USA to its first-ever Olympic medal in women’s rugby at the 2024 Paris Games.

Alev’s story isn’t just about winning or switching sports, it’s about staying grounded and leading with intention. A lot of that mindset comes from her mom, who taught her the power of discipline and the value of seeing things through. Whether it was encouraging her to try out for boys’ varsity hockey or helping her reframe setbacks as stepping stones, her mom’s belief in her gave Alev the confidence to pursue whatever path she chose. That, combined with a natural gift for athleticism and a relentless work ethic, shaped how she moves through the world. These days, Alev carries a philosophy of being kind to herself, staying mentally tough while also giving herself grace in hard moments, and always pushing the edge of her own potential.

In this one, Cody talks to Ben Weissenbach. He’s an environmental journalist and the author of “North to the Future.” It’s a book about Alaska, but also about uncertainty, responsibility, and the quiet, sometimes uncomfortable process of learning how to see. Ben spent time in the Brooks Range and Fairbanks with Roman Dial, a professor of biology and mathematics; Kenji Yoshikawa, a permafrost scientist; and Matt Nolan, a research professor and founder of Fairbanks Fodar, a remote sensing and mapping company. What Ben came away with was a better understanding of climate change, and a deeper reckoning with what it means to pay attention, to feel out of place, and to try to belong in a world that’s changing faster than we can map.

Ben grew up in Los Angeles, where he rarely questioned the role nature played in his life. It was just background, something peripheral to human activity. But years later, after spending time in the Brooks Range, that perspective shifted. He began to grasp the scale and the power of natural systems, and how his own lifestyle—comfortable, urban, and screen saturated—was directly connected to changes happening in some of the most remote places on Earth. He reflects on how many people today, especially younger generations, are growing up in a world mediated by screens, and how that can make it harder to engage with nature. He says that the tools we rely on are easy to use, and they’re culturally reinforced, which makes stepping away from them feel unfamiliar, even alienating. But it was that discomfort, of feeling out of place in the wild, that ultimately opened the door to seeing it more clearly.

In this one, Cody talks to Luc Mehl. He’s an adventurer, educator, and the author of “The Packraft Handbook.” He’s traveled over 10,000 miles across Alaska using only human power — by foot, ski, paddle, bike, and even ice skate. He’s traversed all of the state’s major mountain ranges, competed in more than a dozen Wilderness Classics, and has become one of the most trusted voices in wilderness risk management. But what makes Luc’s story especially compelling isn’t just the miles he’s covered, it’s how those experiences shaped his philosophy around safety, decision-making, and the responsibility we all carry in wild places. He says that it took the loss of a friend for him to wake up to the dangers of packrafting. So, over the past 10 years, he’s made a point of developing a safety culture within the packrafting community, and within the Alaska recreation community at large.

Luc has shaped his entire life around the wilderness, in the miles he’s traveled and in how he approaches risk, safety, and growth. These days, it’s not about proving himself — it’s about what it means to be a good partner, to make it home safely, and to keep going year after year. He’s hesitant to call himself an explorer, knowing the deep Indigenous history of Alaska’s landscapes, and instead calls himself a visitor — someone who’s still learning. And what he’s learning now isn’t just coming from trips or new tech, but from sociology and self-help books — tools that help him slow down, stay aware, and better care for himself and the people he travels with. Because progress comes from the lessons that follow our mistakes, the moments that remind us of how awareness, humility and patience are what keep us moving forward.

In this one, Cody talks to author and multi-disciplinary artist Tessa Hulls. She recently won the Pulitzer Prize for her graphic memoir, “Feeding Ghosts.” It’s about three generations of women in her family — her grandma, her mom, and herself — and the ways their lives were shaped by political violence, migration, silence and survival. The book moves across continents and decades, weaving together personal history and national trauma. It examines what it means to be stuck in time, and carrying the reverberations of inherited trauma. It also confronts the fallibility of memory — what we remember versus what actually happened — and the tension between being Chinese and being American. Tessa’s grandma would have been the keeper of the family’s history, but she was a locked box — often medicated and unable to speak much English. So, at 30, after spending most of her life running from the weight of her family’s story, Tessa realized that if she didn’t confront it, she risked becoming the next generation of collateral damage.

Tessa’s been coming to Alaska for the past 14 years, and says that there’s nothing that makes her feel more at home than being alone in the backcountry. Drawn by the scale of Alaska’s wild places and the way they offer a kind of perspective she hasn’t found anywhere else. It provides her with moments that dissolve ego — when the vastness of the landscape reminds her of how small she is. The people are in tune with change, and the shifting seasons shape daily life and identity. It’s freeing and grounding at the same time.

The outdoors has shaped nearly every part of Tessa’s creative life, and it played a major role in the writing of “Feeding Ghosts.” It offered her the solitude and clarity she needed to confront her family’s story, and it was during a stint working as a chef in Antarctica that she first began teaching herself to draw comics. She says she didn’t have a choice when it came to writing it — it wasn’t a passion project, but a responsibility. She felt summoned by her family’s ghost to break the silence and carry their story forward. And while she has no plans to write another book, she’s now thinking about how to use the attention the memoir has brought her to uplift other artists in Alaska.

Photo courtesy of Gavin Doremus

Nicholas Galanin is a Tlingit and Unangax̂ artist and activist whose work includes sculpture, installation, music and performance — and it’s always in conversation with history, land and power. He creates art that honors Indigenous traditions and confronts the structures that have sought to erase them; it challenges colonial narratives while inviting reflection on language, identity and the legacy of removal. He says that art can be a driver of change, a way to shift perspectives and push systems toward accountability and transformation. Whether he’s calling out institutional inaction, reclaiming ancestral knowledge or amplifying a suppressed language, his work insists that Indigenous culture is not a relic of the past, it’s a living, evolving force for justice and transformation.

Nicholas is also a musician, a collaborator in projects like Ya Tseen and Indian Agent. He talks about music as something fleeting but emotionally precise, capable of transmitting what words often can’t — that it’s a mindful practice rooted in listening, gratitude and presence. He describes the creative process as a kind of alchemy, where different skills and experiences come together in unexpected ways to produce something that transcends the moment. Be it through art or music, his work challenges artificial boundaries — between genres, between people and between past and future. He unravels divisions that are often rooted in systems of control rather than necessity, and makes room for something more fluid and expansive — something grounded in genuine connection, shaped by feeling and driven by the possibility of imagining a different way forward.

Elizabeth Merritt is the founding director of the Center for the Future of Museums at the American Alliance of Museums. It’s her job to track cultural, technological, environmental, political and public health trends — and figure out what they might mean for museums and the communities they serve. She thinks about things like: what role could blockchain play in the art world? Could it allow artists to permanently bake royalties into their work, so that they get a share on future resales? Could museums help lead that kind of change? For Elizabeth, this is personal work: growing up, museums were her favorite places to learn and explore. She did well in school, but she learned more wandering the halls of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History on her own. It was a space that nurtured her curiosity. And that curiosity, a belief that museums are places where we can choose to learn, shapes how she sees the future.

Elizabeth says that she approaches her work like a classic futurist: she reads widely — from academic research to news articles to social media — absorbing as much as she can across disciplines. She also draws inspiration from science fiction, especially dystopias, usually the ones that highlight problems and pathways forward. But her job isn’t just about anticipatory practices and strategic foresight, it’s about preparing museums for the future. So, she’s careful to distinguish trends from fads — trends have direction and persistence, while fads fade. For example, when it comes to climate change, she sees museums as cultural institutions as well as potential anchors of community resilience, helping people adapt to extreme heat, cold and severe weather. Still, she says the biggest challenge right now is twofold: how museums can remain economically sustainable and intellectually independent — and, more importantly, how they can hold on to public trust. Museums are among the most trusted institutions in American life, and she believes that trust is a powerful tool for reshaping a better world.

In this Chatter Marks series, Cody and co-host Dr. Sandro Debono talk to museum directors and knowledge holders about what museums around the world are doing to adapt and react to climate change. Dr. Debono is a museum thinker from the Mediterranean island of Malta. He works with museums to help them strategize around possible futures.

Julie Decker is the director and CEO of the Anchorage Museum. But before that she practiced as an artist and ran her own art gallery. Since then she’s fostered a belief in the power of museums to spark action — whether that means picking up a paintbrush, reading a new book, or seeing the world differently. Her connection to the Anchorage Museum runs back to childhood, when it was little more than a single room with a borrowed collection. Her dad was a visual artist and an art teacher; he was her earliest and most influential guide into that world. He taught her to be an observer — to notice the small things — and she watched as his own work appeared in solo shows and juried exhibitions at the museum. So, for Julie, the Anchorage Museum isn’t just a workplace; it’s been a constant presence in her life, shaping her sense of art, community and possibility.

In the work she does now, Julie envisions the Anchorage Museum as less a keeper of artifacts and more of a living platform for Alaska’s stories. It acts as a collaborator and a partner — a place that listens to communities, amplifies the voices of Alaskans and connects local narratives to global conversations. In her view, Alaska’s relatively small population allows individual creativity and innovation to ripple widely, making it vital to highlight imaginative thinkers, cultural disruptors and non-Western ways of knowing. That means rethinking what it means to collect — not simply holding objects, but being a responsible host and steward of the stories they carry.

In Alaska, where the natural world shapes identity and guides daily life, the museum’s role is to reflect how environmental change, Indigenous lifeways and community resilience intersect. Some projects take the form of exhibitions, others emerge as films, books, podcasts, newspaper series, or collaborations with musicians. Whether the work is local or part of an international conversation, Julie believes it must be rooted in place — fluid, adaptable and focused on a shared future that feels possible and inhabitable.

In this Chatter Marks series, Cody and co-host Dr. Sandro Debono talk to museum directors and knowledge holders about what museums around the world are doing to adapt and react to climate change. Dr. Debono is a museum thinker from the Mediterranean island of Malta. He works with museums to help them strategize around possible futures.

In this one, Cody talks with Eric Heil. He’s an educator and a legendary Arctic Man competitor. Alongside his longtime snowmachine partner, Len Story, Eric won five times. He started competing in Arctic Man in 1990 at the age of 30, and from the beginning, he immersed himself in the event — not just as an athlete, but as part of the crew. He helped with course safety and setting up markers at First Aid, the critical release point where the skier detaches from the snowmachine at the top of the uphill tow. He was the first skier to break the five-minute barrier, clocking in at exactly four minutes — an Arctic Man record at the time. It would take 30 years before anyone broke four minutes, something he attributes to better snow conditions, evolving course design, improved equipment and a rising level of competition.

He was also one of the first racers to bring a technical mindset to the event, experimenting with waxes, analyzing the terrain, monitoring snow temperatures, tracking weather patterns, adjusting his line based on changing snowpack, and timing his transitions to maximize speed and efficiency throughout the course. After nearly three decades of running the course — his last race was in 2018 — Eric says he’s run it more than anyone else.

Eric's path to becoming a high-speed athlete started early. He learned to ski when he was just four years old, and by six he was skijoring. That early exposure to speed and unpredictability planted the seed for a lifelong pursuit of elite competition. In college, he raced for the University of Alaska Anchorage and set his sights on becoming a world champion downhiller. As a world-class athlete, he was comfortable reaching 90 miles per hour on his skis. That kind of speed requires more than just fearlessness — it demands focus, precision and the ability to see what isn’t always visible. Eric says downhill skiers rely heavily on visualization because when you're racing across long stretches of terrain at speeds so fast they blur your vision, you can’t always react in real time — you have to anticipate. That means memorizing every feature of the course ahead of time and trusting your muscle memory to guide you through. He says that even now, he can close his eyes and mentally replay the details of every downhill course he's ever raced.

Annesofie Norn is the Head of Communications and Lead Curator at the Museum for the United Nations, or UN Live for short. With a background in placemaking and art practice, she specializes in designing experiences that resonate across borders and mediums. Her work often explores how art and storytelling can serve as powerful tools for social transformation on a global scale. Before joining UN Live, she worked on art exhibitions and contemporary theatre productions, which often explored hidden stories by posing unexpected questions and making surprising connections. She brings that same curiosity and creative instinct to her work today, helping reimagine how global stories are told and shared.

At UN Live, Annesofie is helping shape what she calls a “borderless museum” — one without a physical building — designed to meet people where they already are. UN Live operates through the power of popular culture, creating immersive experiences that extend beyond traditional museum walls. It aims to tap into the cultural spaces people already love — like music, film, sports and gaming — and use those genres to spark awe, empathy and meaningful action. Rather than asking people to enter a curated space, UN Live enters theirs, collaborating with local communities and cultural traditions to develop initiatives that feel relevant and transformative. Whether it’s amplifying unheard voices or suggesting new ways of being in the world, the work of UN Live is about using the material of society to imagine better futures.

In this Chatter Marks series, Cody and co-host Dr. Sandro Debono talk to museum directors and knowledge holders about what museums around the world are doing to adapt and react to climate change. Dr. Debono is a museum thinker from the Mediterranean island of Malta. He works with museums to help them strategize around possible futures.

Mike Radke is the co-founder and executive director of The Ubuntu Lab, a global education nonprofit that teaches people how to navigate cultural differences with curiosity, humility and empathy. Mike approaches the world with a learner’s mindset, believing he almost always has more to learn than to contribute. For him, that belief isn’t abstract, it’s personal, shaped by years of travel, work in public health and education, and a formative interaction nearly two decades ago with Archbishop Desmond Tutu in South Africa. The two met after a sermon in Cape Town, where Tutu spent hours speaking with Mike about his research on post-apartheid reconciliation. That conversation planted a seed: that forgiveness and collective healing aren’t just moral ideals, they’re practical tools for building communities that can hold disagreement, endure pain and still move forward together.

The Ubuntu Lab began as an academic project, Mike’s dissertation on nonviolence. It’s since grown into a living, breathing network of workshops, learning spaces and small-scale initiatives in over 40 countries. Its mission is to foster empathy and understanding — especially among young people — by encouraging honest, sometimes uncomfortable conversations about identity, belonging and conflict. At its core is the African philosophy of ubuntu: “I am because we are.” Mike and his collaborators co-create experiences that are less about delivering answers and more about sparking dialogue — sessions built around provocation, open-ended questions and the idea that everyone in the room has something to contribute. Rather than build a single institution, they embed within communities, remaining flexible, responsive and grounded in relationships.

In this Chatter Marks series, Cody and co-host Dr. Sandro Debono talk to museum directors and knowledge holders about what museums around the world are doing to adapt and react to climate change. Dr. Debono is a museum thinker from the Mediterranean island of Malta. He works with museums to help them strategize around possible futures.

In this one, I talk to Katie Ringsmuth. She’s the Alaska State Historian, the Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer and the creator of the NN Cannery History Project, a seven-year effort to preserve and interpret the stories of the people who powered one of Alaska’s most historic salmon canneries. For Katie, this story is personal. She grew up around the NN Cannery in South Naknek, where her dad worked for decades, eventually becoming the last superintendent of the Alaska Packers’ Association. He started in 1964 as a young college graduate in Kodiak, doing whatever odd jobs needed doing — from sorting crab to running the entire operation at the NN Cannery. Under his leadership, the cannery shifted away from the rigid, old-school model of command-and-control superintendents — “Tony Soprano–style,” as Katie puts it — and toward something more humane. He created housing for families, hired women and built a workplace that people returned to year after year.

The NN Cannery History Project is more than just about the processing plant, it’s about preserving its historical importance and honoring its workers. The cannery itself was a cultural crossroads with a workforce that included Alaska Native peoples, Scandinavians, Italians, Japanese, Chinese, and Filipino laborers. Canned food revolutionized how people ate. It made it possible to preserve and transport perishable foods across vast distances, reshaping global diets and economies — and the NN Cannery was a key player in that transformation. Originally built as a saltery in 1897, the NN Cannery went on to produce more canned salmon than any other cannery in the state. Katie’s work on the NN Cannery History Project ultimately led to the site being listed on the National Register of Historic Places, a recognition that underscores its national significance. Throughout the project, Katie explores how Alaska fits into the global history of canned food and how preservation — both of fish and of stories — can change the way we understand place, labor and legacy.

Dr. Stefan Brandt is the Director of Futurium in Berlin, a hybrid museum experience and public platform dedicated to exploring the future. With a background in literature, philosophy, cultural studies — and a lifelong interest in music — Dr. Brandt has worked at the intersection of culture, science and civic life. Before leading Futurium, he held senior roles at major cultural institutions across Germany, where he championed interdisciplinary thinking and public engagement. He says it’s always been his intention to make a change, to improve the institutions he leads and, more broadly, to contribute to a better society. At Futurium, that mission continues: creating a space where people are invited to learn about the future and how they can help shape it.

Futurium isn’t a traditional museum, it doesn’t have a permanent collection or fixed exhibitions. Instead, it operates as a dynamic, evolving space designed to spark curiosity and conversation about the future. Dr. Brandt describes this absence of static artifacts as both a freedom and a challenge: it allows Futurium to be more agile and responsive, but it also requires continual reinvention. At its core is a question posed to every visitor: “How do I want to live?” To help people grapple with that question, Futurium presents ideas and scenarios grounded in science, media trends and public discourse. Each major theme — like the future of housing, health, nutrition, or democracy — is developed over time through in-depth research and collaboration with experts. Rather than offering definitive answers, Futurium encourages people to imagine and help shape a sustainable, participatory future.

In this Chatter Marks series, Cody and co-host Dr. Sandro Debono talk to museum directors and knowledge holders about what museums around the world are doing to adapt and react to climate change. Dr. Debono is a museum thinker from the Mediterranean island of Malta. He works with museums to help them strategize around possible futures.

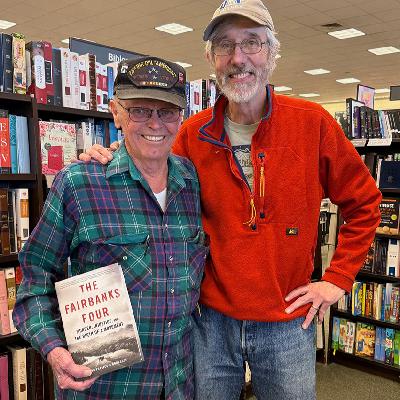

In this one, Cody talks to journalist and retired professor Brian Patrick O’Donoghue, whose decades-long investigation into the wrongful convictions of four young men of Alaska Native and Native American descent — known as the Fairbanks Four — helped reshape one of the most important criminal cases in Alaska history. Brian’s investigative reporting class at the University of Alaska Fairbanks became more than an academic exercise, it turned into a collaborative effort that collected interviews, uncovered new evidence, and helped bring national attention to the case. In his new book, The Fairbanks Four, he traces that journey in painstaking detail, from questionable confessions and buried evidence to the grassroots push for justice that eventually caught the attention of The Innocence Project.

When Brian joined the faculty at UAF, he knew exactly what he wanted to focus on. Even though he hadn’t covered the Fairbanks Four case as a reporter at the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, it had always raised unanswered questions for him, ones he couldn’t ignore. So, when he was asked to identify a research area, he returned to that case and built a class around it. At a glance, it might have looked like a traditional classroom, but in reality it functioned more like a working newsroom, with students knocking on doors, flying to remote communities, and surfacing details that hadn’t been fully explored in court. And then when their findings began to gain traction in legal filings, Brian realized they were no longer just reporting on the case, they were influencing it.

In this episode of Chatter Marks, we explore the lingering impact of the Cold War on Alaska, a state that stood on the frontlines of a global standoff. Through perspectives rooted in art, journalism, history, and geopolitics, we trace how Cold War-era decisions reshaped Alaska’s communities, economy, environment and sense of identity. And how it continues to influence Alaska’s security policies and relationship with the rest of the world.

Ben Kellie is an entrepreneur, a writer and someone who’s spent a lot of time thinking about how to build things that matter. He grew up in Alaska, learning to fly planes with his dad. It was a hands-on education in problem-solving, resilience and staying calm under pressure. That mindset carried him through early work on rocket launches and landings at SpaceX, and later, into founding The Launch Company, a startup that developed modular, scalable launch systems for rockets. He sold it in 2021. These days, he’s working on a new venture called Applied Atomics, building compact nuclear power systems that are designed to provide energy-intensive industries with clean, reliable power. More than anything, though, he’s interested in where Alaska fits into the global future: how we move beyond boom-and-bust cycles, invest in our own talent and create businesses that are both rooted here and relevant everywhere.

Ben says that the investment he’d like to be known for hasn’t happened yet, but his goal is to demonstrate what’s possible in Alaska. That includes moving beyond our dependence on oil, and considering where Alaska’s people and economy might be in 50, 100, or even 1,000 years from now. While the specifics of future technology are hard to predict, some needs remain constant: food, clean air, clean water and reliable energy. These are the issues he focuses on when he thinks about the problem he would like to be known for solving. They’re ones that meet basic human needs. And writing helps him work through these ideas. He says it’s a tool for making sense of complex decisions, checking assumptions and mapping the long view. It’s also how he slows down, reflects and emotionally processes what he’s building. Because, for him, it all comes back to family and community.

Jamar Hill is a coach now, but before that, he was a pro baseball player in the Mets organization. He grew up in Anchorage, where playing baseball wasn’t always easy: limited facilities, long winters and not much opportunity to play year-round. He says that in Alaska, you get about a quarter of the playing time compared to other places. But in a way, that made him love the game even more. As a kid, he followed the Alaska Baseball League, one of the best summer leagues in the country. It brought in top talent every year — future first-round draft picks — and watching those games gave him an early sense of how the baseball world worked. By the time he was 16, most of the teams he played on included at least one future Major League player. And by the end of high school, he was drafted by the Mets. He became one of their top power prospects — a lefty bat who hit right-handed pitching especially well. He went on to hit over 100 professional home runs. But beyond the stats, it was his early exposure to high-level talent, and his ability to adapt, that shaped his perspective. That perspective is still with him today — as a coach, a mentor and someone who’s all about creating opportunities for the next generation.

Today, Jamar is focused on giving back to the community that raised him. As a youth coach and founder of RBI Alaska, he’s spent the last 10 years helping young athletes grow — as players and as people. He’s currently leading the development of the Mountain View Field House, a year-round indoor training facility that will give local kids access to the kind of resources he didn’t have growing up. For him, coaching isn’t just about skill development, it’s about building character, creating opportunity and showing kids that their environment doesn’t have to limit their ambition. He mentors with intention, using his own experiences in professional baseball to help young players navigate the mental, emotional and physical sides of the game. Through that work, he’s helping shape confident, resilient athletes who are prepared for whatever comes next, on the field or off.