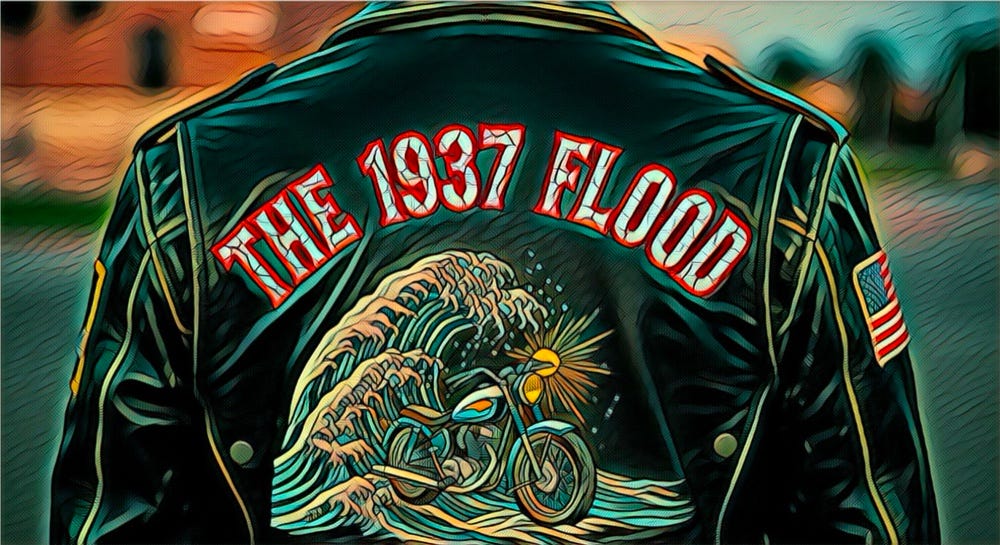

Discover The 1937 Flood Watch Podcast

The 1937 Flood Watch Podcast

The 1937 Flood Watch Podcast

Author: Charles Bowen

Subscribed: 0Played: 1Subscribe

Share

© Charles Bowen

Description

Each week The 1937 Flood, West Virginia's most eclectic string band, offers a free tune from a recent rehearsal, show or jam session. Music styles range from blues and jazz to folk, hokum, ballad and old-time. All the podcasts, dating back to 2008, are archived on our website; you and use the archive for free at:

http://1937flood.com/pages/bb-podcastarchives.html

1937flood.substack.com

http://1937flood.com/pages/bb-podcastarchives.html

1937flood.substack.com

250 Episodes

Reverse

Our Randy Hamilton was born to sing songs like this. He and Danny Cox brought us “Spooky” last summer and we’ve been loving it ever since. Especially when we added Sam St. Clair’s funky harmonica and Jack Nuckols’ tasty percussion.About the SongAs reported here earlier, while The Classics IV made the lyrics famous with a chart-topper in the fall of 1967, the story of “Spooky” began several years earlier in an Atlanta club. Following a show sometimes in 1965, saxophonist Mike Sharpe (Shapiro) and his band mate pianist Harry Middlebrooks Jr. began riffing on the George Gershwin classic, “Summertime.”As they improvised, they realized they had stumbled upon something special. As they continued, the duo developed their own melody, to which Sharpe randomly assigned the name “Spooky.”The original version was recorded as a jazz instrumental featuring strange high voices to enhance the eerie vibe; it eventually peaked at No. 57 on the U.S. charts in January 1966.Sharpe and Middlebrooks initially thought the song’s life cycle ended there, but a year later, The Classics IV added those lyrics about that “spooky little girl like you,” propelling the track to No. 3 on the Billboard 100. Harry’s StoryMeanwhile, as “Spooky” was conquering the airwaves, co-writer Harry Middlebrooks was entering one of the most high-energy phases of his career: touring with Elvis Presley. It was the fall of 1970 when Middlebrooks received a call from Elvis’s producer, Felton Jarvis, inviting him to join The King’s first tour in 10 years.Middlebrooks served a unique dual role on the road: he performed as part of the opening act to warm up the crowd and sang tenor in the backup quartet, providing the vocal harmonies essential to Elvis’s ‘70s sound. In a moment of professional synergy, Elvis, who was fond of “Spooky,” actually performed a cover of the Sharpe-Middlebrooks’ hit during various live shows and rehearsals in 1970.Beyond his most famous composition, Middlebrooks established himself as a prolific figure in the entertainment industry. He composed for television and penned more 300 tunes recorded by such diverse artists as Tom Jones, Liberace and The Oak Ridge Boys.Middlebrooks recorded several albums for Reprise and Capitol Records and established himself on the club scene in Southern California, eventually singing at more 80 clubs. He became an in-demand session and backup singer for Neil Diamond, Anne Murray, Marty Robbins and others. In particular, he relished his seven-year run backing Glen Campbell for his Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe concerts.Another Helping of Randy Tunes?So, has today’s podcast got you hankering for more tunes from Randy Hamilton? Coming right up!Just drop by the free Radio Floodango music streaming service and click into the Randy Channel for a randomized playlist of Hamilton-centric songs from The Flood repertoire. Or just click here to take the express route! This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

The fun of playing some songs is that we just never know what we’re going to hear. This George Gershwin piece has been like that ever since Danny Cox brought us better chords for it a year or so ago. Now the song is like a shiny little red convertible parked in the garage just waiting for the next sunny day. You and your buddies pile in, not knowing where you’re going, just enjoying the company and the sights and the sounds of each other’s laughter. Hop in! We’re going for a joy ride!About the SongAs reported earlier, “Lady Be Good” has been a perennial party favorite for more than a century now.Nineteen-Twenty-Four was a watershed year for Gershwin. After spending more than a decade pounding the pavement in New York’s Tin Pan Alley, he composed his landmark "Rhapsody in Blue." Then, alongside his brother Ira, George scored his first major Broadway hit, the musical comedy Lady Be Good, which ran for more than 300 performances.The enduring significance of the show’s title tune, "Lady Be Good," lies in its rare ability to transcend musical eras. A unique entry in the Great American Songbook, it beautifully bridged two distinct jazz ages, surviving the transition from the loose Dixieland style of the Roaring Twenties to the smooth swing sound of the 1930s.A favorite among jazz legends as diverse as Charlie Parker and Lester Young, the song’s rich history also includes interpretations by vocal icons like Ella Fitzgerald and Mel Tormé.For more on the back story of this song, see this earlier Flood Watch entry.More Floodifaction?And if this has you hungry for a little more of the band’s jazzier selections, drop by the free Radio Floodango music streaming feature and click on the “Swingin’” Channel.Click here to give it a spin. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Some songs just seem to go right to the heart of what connects us all, especially when the subject is hard times.This song from a recent Flood rehearsal is often considered a classic example of the old notion of singing the blues to get rid of the blues. Historically the tune also represented liminal moments for two distinctively different musical artists.About the SongAs noted in an earlier Flood Watch article, Ray Charles wrote and recorded “Hard Times (Who Knows Better Than I?)” in the mid-1950s during a period of heavy creative output at Atlantic Records.But the song languished in the Atlantic vault until the September 1961 release of The Genius Sings The Blues, a highly praised compilation of some of Charles’s earlier singles along with some previously unreleased stuff.While Brother Ray rarely spoke at length about composing these tracks, the origin of “Hard Times” seems deeply rooted in his personal history, especially his relationship with his mother, Aretha Robinson, who died when he was still a teenager.The song also is another marker for those who follow the Ray Charles story. By the early 1960s, Charles had largely stopped writing his own material to focus on interpreting others’ work, making “Hard Times” one of his last significant original compositions.The Eric Clapton ConnectionThree decades later, “Hard Times” marks a period of transition for a great artist of the next generation.Eric Clapton, having recently overcome his battles with drug addiction, viewed his 1989 Journeyman recording sessions as a way to further master his craft, focusing on his love for blues.The lyrics of “Hard Times,” which deal with personal struggle and perseverance, resonated with that personal journey. The song has stayed in the Clapton repertoire. It was later featured on his 1991 live album 24 Nights, recorded at the Royal Albert Hall. More recently in 2025, he revisited it, playing on a cover for Nathan East’s collaborative album with his son Noah, titled Father Son. For more of the back story of ”Hard Times,” check out this earlier Flood Watch article. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Sometimes the chemistry’s right, the stars align — however you want to say it — and the best song of the night is one you didn’t even plan to play.At a recent rehearsal, for instance, the band came in with a number of tunes to focus on. Among them were new songs the guys were just starting to work on. Others were old familiar numbers that they were polishing up to include in the next recording session for the new album.Progress was made in the first hour or so on each of these fronts. Then between songs, on an impulse, Charlie Bowen reached for his resonator guitar. As you’ll hear in this track, while the guys were chatting, he started noodling on the strings with his slide.Suddenly they found themselves playing a tune that hasn’t popped up for a while at the weekly rehearsals, and just like that they were sharing their favorite moment of the entire night.About the SongAs reported earlier, “Driving Wheel” was written by Canadian folksinger David Wiffen for his self-titled debut album on Fantasy Records back in 1970.Alas, the album received spotty promotion so the song was not widely known until it later appeared on Tom Rush’s own self-titled album, his first for Columbia Records.Since then, “Driving Wheel” has become something of a signature song for Rush, still today regularly making the set list for his shows around the country. Other artists also have covered the song over the years, notably David Bromberg (who 50 years ago played dobro on Rush’s classic rendition) as well as Roger McGuinn and The Cowboy Junkies.For more about the song’s back story, see this earlier Flood Watch article. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Redbud trees and mockingbirds, honeysuckle and sassafras. For many a West Virginian, these are emblems of home.And pecan pie. You can’t forget pecan pie. But you gotta be careful how you say it. How you pronounce those words — PEE-con puh-aye, y’un’stan’ — tells us a lot. If you say, puhCAN … well, yeah, we’ll still know what you’re talking about, but we’ll also know you’re not one of us.How the Song Came to BeSuch Appalachian icons and shibboleths were much on Charlie Bowen’s mind as he wrote this song recently, though the real impetus for “Pecan Pie & Sassafras Tea” was a story that his grandma told him a lifetime ago.Grandma Bowen — “Hattie” to everybody on Tyler Mountain — grew up on Eighteen Mile Creek along the edge of West Virginia’s Mason and Putnam counties. Wise in the ways of the woods, she knew her weather signs and what roots to harvest for tonics in the spring and fall, what barks to brew for colds and headaches and other complaints.Hattie also knew her animals. She used to caution, for instance, about telling secrets around mockingbirds, because, well, those darn birds? why, they’d tell them!Tickled at the notion of a secret-telling mockingbird and imagining it making long-distance connections among different sets of lovers, Charlie set to writing this song.Melodic InspirationIts melody has Appalachian roots as well. As part of his current banjo quest, which now has been ongoing about 2 1/2 years, Bowen at one point came across the old tune called “Lazy John,” which comes from the playing of influential Monticello, Ky., fiddler Clyde Davenport.Davenport, who died in 2020 at age 98, once said that he in turn learned the tune from a radio broadcast in the mid-1940s, specifically a recording by Texas musician Johnny Lee Wills (brother of Bob Wills) and his western swing band.Now, Bowen has yet to bring that song into his repertoire (apparently John’s not the only lazy one in this story!), but twists and turns in Davenport’s playing inspired the melody that Charlie ultimately put together for “Pecan Pie & Sassafras Tea.” We hope you enjoy it.More from Charlie?If this little excursion has you thinking that a little more of Charlie’s tunes would further enhance your Flood Friday, remember there’s a randomized Bowen playlist in the band’s free Radio Floodango music streaming service.Click here to reach the Charlie Channel. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Our guitarist Danny Cox paints pictures with his sound. He has a positively uncanny capacity for discovering ways to bring out the colors and textures in all kinds of melodies and to plant stories in the minds of everyone who hears.Just listen to his treatment of this rich old Sonny Burke composition, finding all kinds of new magic and nuance in this poignant melody.About the SongAs reported earlier, “Black Coffee,” written in 1948, spent the first decade of its life as a darling of vocalists. Recording it, for instance, revamped the careers of both Sarah Vaughan and Peggy Lee as their fans grooved on Paul Francis Webster’s sparse, evocative lyrics.But composer Burke knew the potential of his melody as well; he himself performed it on alto sax in 1948. However, about decade passed before the song started getting serious attention as a jazz instrumental. That’s because it was just what a young Ray Charles was looking for.While Brother Ray rarely singled out “Black Coffee” in interviews, he spoke extensively about the artistic philosophy that informed his instrumental treatments during that era. His decision to record “Black Coffee” instrumentally for The Great Ray Charles album was a deliberate effort to be recognized as a serious jazz musician, not just an R&B star on the radio.For that project, his second studio album, Charles avoided his signature vocal style in order to highlight his piano blues with all those Art Tatum-influenced flourishes. For the “Black Coffee” session (April 30, 1956), he deviated from his usual big-band horn arrangements and stripped the performance down to a trio. He was joined on the date by Oscar Pettiford on bass and Joe Harris on drums.Later in his autobiography, Brother Ray, he noted that these sessions allowed him to explore the chord structures of this fundamental jazz standard.Other RenditionsAfter Ray Charles’s performance, other artists took “Black Coffee” on instrumental outings, such as Bobby Scott (1959), Earl Hines (1964) and Earl Grant (1968).Meanwhile, a wide and wildly varied group of singers also have served up “Black Coffee” in the 70 years since its introduction, from Canned Heat (on its 2003 Friends in the Can album) to the Pointer Sisters on 1984’s That’s a Plenty album.k.d. lang’s “darkly twangy” version from her 1988 album Shadowland is considered an essential track in her discography, bringing a new interpretation to the song.Women have been especially attracted to the song, from Petula Clark (1968), Sinead O’Connor (1992) and Rita Cooledge and Gladys Knight (both 1996) to Maria Muldaur (2002) and Marianne Faithful ( 2008).For more about the song’s history, see our earlier Flood Watch article by clicking here.More from DannyMeanwhile, speaking of more renditions, would you like some more Danny Cox tunes for your Flood Friday? We gotcha covered. Visit our free Radio Floodango music streaming service and give the Danny Channel a listen.Click here to set the Danny playlist in motion. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

By the end of his life, Billy Mayhew might well have wished he’d never written that damned song.Oh, it was a hit, all right — the only one the old Baltimore vaudeville piano man ever wrote — introduced to the world by 1930s radio superstar Kate Smith and later jazzed up by the great Fats Waller who got everyone humming the thing.Still, within months of the publication of “It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie,” Billy and his wife and co-author Margaret Konig Mayhew were dragged into court with a demand that they share the song’s mounting royalties.How the Song Came to BeBilly wrote “It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie” in the early 1930s, but after five years of hoofing it around to pitch it in New York’s Tin Pan Alley, he could find no one who wanted to publish it. According to later court documents, Mayhew was about to give up when in June 1935 he met Helen Meehan in the music department of the S.S. Kresge Company store in Baltimore.For nearly two decades by then, Meehan had been employed as a sheet music buyer, meaning she had contacts in the publishing world. Right away, Helen went to bat for Billy, reaching out to representatives of music houses. In early 1936 she landed the song with Broadway publisher Donaldson, Douglas and Gumble, Inc. (If that name rings a bell, it might be because we met the firm’s founder Walter Donaldson back when we talked about his “My Blue Heaven” and again in the back story of his “Makin’ Whoopee.”)When Donaldson published it, “It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie” hit the big time. It was first recorded and released by Freddy Ellis and his orchestra, followed by Kate Smith and then Fats Waller. Dream come true. But before the year was out, Billy’s dream took a nasty turn.The Court CaseIn the Circuit Court of Baltimore City in late July 1936, Helen Meehan sued him, claiming Billy Mayhew himself had done a bit of lying when he promised to give her 50 percent of the royalties if she got the song published. After a two-year court fight, a decree was issued in Meehan’s favor, establishing her as a creditor for $7,163.10 (about $170,000 in today’s dollars). This decision was affirmed on appeal the following spring.However, it appears only the lawyers profited from the case. While Helen Meehan successfully established her claim, she found it hard to collect. Her main obstacle was a representative of the song’s publisher, which placed an attachment on Mayhew’s royalties in New York as early as February 1937.In a desperate attempt to stop that payment, Meehan filed an involuntary bankruptcy petition against the Mayhews, arguing that Billy and Margaret’s failure was a “preferential transfer.” But the U.S. District Court didn’t buy it, dismissing her petition and ruling that the publisher’s claim was based on a lien established years earlier and therefore was not a fresh act of bankruptcy.The Last DecadeAfter that, we lose track of Helen, but Billy and Margaret Mayhew ended their days living and working at a brother-in-law’s boarding house and “truck farm.” Today, incidentally, the farm — located on Bar Neck Road in Cornersville, in Maryland’s Dorchester County — is listed on the state’s Inventory of Historic Properties, all because of its association with the song.No more hit songs came from the couple, though they seem to have kept trying. For instance, the day after Christmas in 1940, Billy and Margaret filed copyright papers for a composition with an intriguing title: “Can’t Do a Thing with My Heart.” Alas, we find no indication that it was ever published or recorded.Billy died Nov. 17, 1951, and Margaret died a month later. Both are buried in Baltimore’s Oak Lawn Cemetery. The Song Lives OnThe Mayhews wrote the song as a waltz, and that’s how Freddy Ellis’s orchestra performed it in its first recording. The early performances — by Kate Smith, Ruth Etting, Vera Lynn, et al — played it straight (very straight).But then also came Flood hero Fats Waller, who never played anything straight. Fats kicked the tune into 4/4 and gave it his signature blend of stride piano and irreverent, satirical humor. For instance, while the ladies Kate, Ruth and Vera all loyally sang the Mayhews’ original lyric “If you break my heart I’ll die,” Fats ad libbed, “If you break my heart, I’ll break your jaw!”From Fats forward, the song that originated as a sappy Tin Pan Alley ballad got its groove on, transforming into a high-energy (often comedic) jazz performance for everyone for the Ink Spots (1942) and Billie Holiday (1949) to Jimmy Rushing (1955) and Tony Bennett (1964) to Steve Goodman (1975) and John Denver (1998).Floodifying ItThis song has rattled around in the Floodisphere for decades but only recently did we decide to give it a spin. Whaddaya think?More Song HistoriesDo you enjoy this back stories on the songs we play? We got a million of ‘em! Well, hundreds, anyway.Drop by the free “Song Stories” archive — just click here to reach it — and you’ll find an alphabetized list of titles. Click on one to reach our take on that particular tune.Or if you’d like to find songs from a specific decade, visit the archive’s “Tunes on a Timeline” department — click here! — to locate songs by their years of origin. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Wrapping up a recent Christmas party at which we had a houseful of friends and neighbors (including our buddy Jim Rumbaugh sitting in as a guest artist), The Flood unwrapped its new anthem to winter. It is this mashup of “Moscow Nights” and “Greensleeves.” Today we make this performance our gift to you. Merry Christmas from the Floodisphere!The SongsLet’s talk about the bits and pieces that make up this jolly seasonal offering.“Moscow Nights”As reported earlier, “Moscow Nights” was composed in 1955 by Russian musician Vasily Solovyov-Sedoy. It was originally entitled “Leningrad Nights,” but, it being the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Ministry of Culture directed it be renamed to celebrate Moscow and directed corresponding changes to poet Mikhail Matusovsky’s lyrics.For the first half dozen years of its life, the song was known primarily in the Soviet Union, The melody didn’t hit the big time in the U.S. until November 1961 when trumpeter Kenny Ball and his Jazzmen recorded it under the title "Midnight in Moscow.” For the recording, Ball was inspired by an arrangement he heard by a Dutch jazz group called “The New Orleans Syncopators” who recorded the melody earlier that year.But there is a lot more to this story. Like when The Chad Mitchell Trio’s controversially battled with the U.S. State Department over performing the song in foreign lands. And like the time that Flood manager Pamela Bowen got kudos for performing the song in its original Russian during her folksinging days as a student at Marshall University. Click here to read these and other “Moscow Night” yarns.“Greensleeves”The song’s musical team mate in this track — “Greensleeves” — probably is the oldest melody we know. It has been associated with Christmas ever since a century and half ago when the tune was set to the verse “What Child Is This?” But the song originally wasn’t religious in nature at all. On the contrary, as reported here, its earlier lyrics told the story of a painful romantic conundrum (with some, uh, subtly salacious references). Popular legend even has sometimes attributed the song’s composition to England’s King Henry VIII, who was said to have written it for the ill-fated Anne Boleyn. That association, though, is wrong, says author Lisa Colton in her book Angel Song: Medieval English Music in History. Colton finds “Greensleeves” originated a generation later, during the reign of Henry’s daughter, Queen Elizabeth I. First published in 1580, the tune was used for a wide variety of 16th and 17th century broadside ballads.And there’s much more to this back story as well. Click here to read it.Reviewing 2025This is our last podcast of the year. We look forward to roaring into 2026 with you all. Meanwhile, if you’d like to get a jump on your auld-lang-syning, you can tune into a randomized playlist of this year’s 52 podcasts via the band’s free Radio Floodango music streaming service. Click here to give it a spin. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

It was 16 years ago tonight at the Christmas Eve-eve-eve party in the Bowen House that the late Dave Peyton gifted us with a classic rendition of his all-time favorite John Prine tune. And fortunately, Pamela Bowen had her camera running to preserve the video above.“Come Back to Us, Barbara Lewis Hare Krishna Beauregard” was introduced on Prine’s 1975 Common Sense album, but the song didn’t really resonate with Br’er Dave until he heard it again about a dozen years later as the opening track on the John Prine Live album.By that time, The Flood had gone in recess, as reported here earlier, but the song was still very much on David’s mind when the band reconvened in the mid-1990s, and “Barbara Lewis” then kept coming back to us in the years to come.About the SongThe late John Prine said in the liner notes for that 1988 “live” album that he wrote “Barbara Lewis” in the summer of 1973 while he was touring Colorado ski towns with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. The lyrics were inspired, he said, by the “leftover hippies” he encountered in the Rocky Mountains, people who had drifted through various counterculture movements and religions without ever making it all the way to California.It was, he said, as if they got to the Rockies and said, “God, I can’t get over that,” and just settled in.Besides that, John added, “I had different friends of mine who went through the ‘60s, from being totally straight or greasers, then turned into hippies, and then into a religious thing. So I created this character who had done all those different things.”About the title, Prine said he got the name Barbara Lewis from the R&B singer (”Hello Stranger,” 1963; “Baby, I’m Yours,”1965). And the rest of the name of the character? “It just falls off the tongue really nicely,” John said, noting he often tried to match a syllable for each note. “I call it the Chuck Berry School of Songwriting. He’s got it so dead-on that you can just read his lyric, and that would be a melody.”More John and More DaveIf this single song doesn’t completely satisfy your Flood needs right now, you can have many more helpings at the band website’s free Radio Floodango music streaming service.For instance, if you’d like more Floodifying of John Prine songs, check out our John Prine Memorial playlist. Click below for the details:Meanwhile, if you’d like to listen again to some of the many beloved tunes featuring our old buddy Dave Peyton, check out the David Channel.Click here to give it a spin! This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Christmas is usually a pretty raucous time in our band room, with old friends coming back around and new friends ... well, new folks just starting to figure us out. Yes, indeed, we do tend to take those tidings of comfort and joy at their word.And our holiday celebration is especially memorable if we can get that jolly ol’ Jim Rumbaugh back into the room, as we did at a recent festive gathering at the Bowen House. To make the season bright, we always try to get Jim doing his bluesy Christmas contribution, a song he calls, “Got My Yule Log Burnin’.”Jim’s path to writing the tune began while he was working at his wife Donna’s greenhouse, which sold Christmas trees every year. As part of the business, Donna made wreaths, which required pieces of greenery. Jim was tasked with taking the reject trees and cutting off their branches so she could use them for the wreaths. This process left him with substantial pieces of pine log, typically five to seven feet long, which he then had to cut into foot-long pieces to be bundled and sold as Yule Logs.While cutting these logs, Jim began pondering the purpose of the items he was creating, wondering if anyone actually burns a Yule Log.“I thought, ‘I wonder if there’s a Yule log-burning song?’ and I started singing, ‘Got my Yule Log burning,’ which sounded a whole lot ‘Got my mojo working!’”Well, after that, all that was needed was a bit of Christmas cheer and space for a couple of well-tempered harmonica breaks. Demonstrating the results, Jim got everyone in the room singing along, as you’ll hear here!To Keep the Holidays Bright…So, Merry Christmas from your friends in The Flood.And for a little more fa-la-la-la-Flood in your festivities in this week’s countdown to Christmas, remember the Radio Floodango free music streaming service has this yuletide playlist.Click here to give La Flood Navidad a spin!More from the Righteous Mister RumbaughMeanwhile, if today’s podcast has you wanting more helpings of Jim Rumbaugh’s bluesy offerings, you’re in luck! Jim is the star of a popular episode in the “Pajama Jams” video series that The Flood released back in 2021. Click below to check it out! This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

The story goes that folkie John Denver was just 22 years old when he played at Arizona’s Lumber Mill Club in Scottsdale and met a girl named Bobbie Wargo.The two had much in common. Both grew up in military families. Both were musicians and aspiring songwriters. Both were looking for love.And love was what they found as they played together at her parents’ piano. It was for her that John wrote one of his first songs. And “For Bobbie” was to be the first original tune that Denver ever recorded. I’ll walk in the rain by your side, I’ll cling to the warmth of your hand…Bobbie Wargo may have contributed to the song’s lyrics; there is evidence that she also might have been the inspiration for his next song, “Leaving on a Jet Plane.”(All of this was half a decade before John Denver met the iconic “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” recorded it and, as reported here earlier, became forever an honorary Mountaineer.)“For Bobbie” was, as Denver later told writer Deborah Evans Price in American Songwriter magazine, “an early attempt to order my romantic thoughts.”The Song’s Recording HistoryThe song was first recorded by the Mitchell Trio under the truncated title of “For Bobbi” in 1965, the same year in which Denver joined the group, replacing founder Chad Mitchell who had moved on to a solo career.The following year the song took a whole new turn when Mary Travers (of Peter, Paul & Mary) rechristened it “For Baby” and recorded it to honor her young daughter Erika. Travers changed the meaning to reflect a mother’s love for her newborn, and this version gained significant popularity. The song appears on the 1975 Peter, Paul & Mommy, Too album as part of a medley entitled “Poem for Erika/For Baby” That wasn’t PP&M’s first outing with it; nine years earlier, in 1966, “For Baby (For Bobbie)” appeared on the group’s sixth studio release called simply Album.Meanwhile, Denver himself re-recorded the song — this time also listing it as “For Baby (For Bobbie)” — on his popular 1972 Rocky Mountain High, his first Top-10 album.In the seven years between Denver’s first and second release of the song, a half dozen other artists covered “For Baby (For Bobbie)” including Bobby Darin (1966), Dion and the Belmonts (1967) and Anne Murray (1968).Our Take on the TuneOne of the first tunes that Charlie Bowen and his cousin Kathy Castner did when they started singing together more than 30 years ago was Denver’s lullaby-like love song. So it’s only natural that “For Baby (For Bobbie)” is in the mix whenever Kathy gets to make one of her rare trips from Cincinnati to Huntington to sit in with the band. Here’s a take on the tune from last weekend.Since Flood harmonicat Sam St. Clair couldn’t make it that evening, we corralled the player whom Sam lovingly calls his “overstudy,” the incomparable Jim Rumbaugh, to sit it and bring some memorable solos.And Now From the Wayback Machine…Oh, and want a little trip down mem’ry lane? Here’s a video of a For Baby Moment that Pamela Bowen caught almost a decade and half ago:From the summer of 2011 in the Bowen House, this performance is complete with sweet solos by Dave Peyton and Jacob Scarr. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

At a good rehearsal — and, heck, that’s just about every rehearsal nowadays — none of us really wants it to end. Oh, sure, we get tired — two hours of hard picking take a toll — but as Gladys Knight used to say, none of us wants to be the first to say goodbye.In fact, as you hear at the conclusion of this week’s podcast, which features the final tune of a recent rehearsal, we often even keep extending the ending, jockeying to be the one to play the last note.The moment is always really fun if that last tune of the night is an especially goofy one, and you can’t get much goofier than “Yas Yas Duck.”About the SongThis late 1920s hokum song came into The Flood’s life more than 40 years ago. In fact, it had its public debut at what turned out to the last of those semiannual music parties that birthed the band, as seen in this excerpt from the “Bowen Bash Legacy Films” series:In those days — the above audio is from September 1981 — chasing down the history of these quirky little tunes was challenging. The World Wide Wide was still more than a decade away, so to suss out songs’ back stories, we had to rely on often sketchy liner notes on rare albums and on even rarer books covering esoteric genres.We learned our version of the song from a 1973 Yazoo Records compilation called Tampa Red, Bottleneck Guitar (1928-1937), the same record we studied so we could cop other Tampa tunes like “What’s That Taste Last Gravy?” “Black Eyed Blues” and “No Matter How She Done It.”Mastered by Nick Peris, the LP featured liner notes by Seattle bluesman John Miller who gave us no hint of the song’s colorful evolution. For years, we just assumed that it was another of Red’s collaboration with Georgia Tom Dorsey.Only recently were we able to use web resources to determine that the song traces back to what Wikipedia characterizes as “a ‘whorehouse tune,’ a popular St. Louis party song,” first recorded in January 1929 by a great St. Louis piano pounder named James “Stump” Johnson. It would be four months later before Tampa Red and Georgia Tom recorded their version in Chicago.For more about “Yas Yas Duck” (and all its various alternate names), check out our earlier Flood Watch article by clicking here.Latest Floodification of The DuckAs you’ll hear on this track, this hokum classic, whether it comes at the beginning of an evening of music or at the end, is always good for a few laughs.As noted above, it was 1981 when The Flood first publicly played the tune. But the song was still very much in Flood Consciousness 20 years later when the band made its first studio album. Click the button below to hear the album track from 2001: This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

This song, while beautiful at any time of the year, is especially resonant at the dawn of a new holiday season. So this morning, as our Thanksgiving gift, here’s The Flood’s latest performance of the late Michael Peter Smith’s evocative “Spoon River.”Thanksgiving, as a season celebrating the bonds of friends and families, is a particularly good time to appreciate a song that reminds us in the very first verse how “all our lives were entwined to begin with.”As we noted an earlier in Flood Watch article, Smith once famously commented, “I like songs that delight in giving you a picture,” and “Spoon River” does that in spades, from images of riverboat gamblers and Union soldiers to the calico dresses in the attic along with Grandfather’s derringer case.Thanksgiving gatherings often involve opening drawers, unlocking old doors and retelling stories to reconnect with ancestors through the objects they pass down.And more. Our favorite lines, at the end of the second verse — There are words whispered down in the parlor, a shadowy face. The morning is heavy with one more beginning ….— evoke the way that memory itself seems to drift through a house during the holidays, the past present with the living. May this song bring you joy and sweet memories as you come and ride through the morning. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Here’s another tune that Danny Cox has brought to us from his decades of lovingly listening to Chet Atkins and Jerry Reed’s famous recordings.One of Jerry’s composition, “Baby’s Coming Home” is a standout tune that was introduced on 1974’s landmark Chet Atkins Picks on Jerry Reed album.As reported here earlier, Atkins and Reed were not only esteemed guitarists but also good friends who shared a profound musical chemistry. A major figure at RCA, Atkins was instrumental in bringing Reed to the label.The album testified to Atkins’ continued endorsement of the younger man’s talent, showcasing interpretation of 10 of Reed’s unique and often humorous compositions. Chet and Jerry were known for their distinct fingerpicking styles, drawing inspiration from pioneers like Merle Travis and incorporating their own original, complex techniques. This is what attracted Danny Cox to their work when he was still just a teenager learning to pick.About the SongJerry Reed wrote “Baby’s Coming Home” around the time Chet was coming up with the plans for his 1974 tribute album. Atkins’ rendering of the song is the first track of the disc’s B side. Incidentally Jerry himself performed on only two of the album’s tracks (”Squirrely” and “Mister Lucky,” and sadly not on “Baby’s Coming Home”). However, a few years later, he and Chet did pick the tune together on TV. That wonderful, light-hearted segment was preserved on this YouTube video:A Muppet MomentBy the way, four years later, “Baby’s Coming Home” made a curious comeback. This time with a tuba-and-banjo-heavy Dixieland-flavored arrangement, the song was the soundtrack for a sketch called “Lunchtime” during Episode 316 of The Muppet Show. Check this out:More Atkins-Reed Collaboration Chet Atkins Picks on Jerry Reed reminded many fans of Chet’s Grammy-winning 1970 Me and Jerry release, an all-acoustic, instrumental album that featured the two buddies teamed up on a range of songs, from country and pop covers to original instrumental workouts.Several decades later, this collaboration was followed by another celebrated joint effort, the 1993 Grammy-winning Sneakin’ Around album. More from Danny?If all this has you in the mood to put a little more Danny Cox into your Flood Friday, drop by the free Radio Floodango music streaming service and give the Danny Channel a spin.Click here to check it out! This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Educated ears in the summer of 1957 were still trying to decide if this new rock ’n’ roll thing was really music’s future or was just a passing fancy.Two summers had passed by then since the new sound burst upon the American scene. The ear-opening “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley & His Comets was quickly followed by Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” and Little Richard’s “”Tutti Frutti.”The following summer the rock kept rolling, when The King arrived. This new kid, Elvis Presley, topped the charts for weeks on end with “Heartbreak Hotel,” with “Hound Dog,” with “Don’t Be Cruel.”But by 1957, the cigar-chomping bigwigs in the record company boardrooms still weren’t sure. Not sure sure, you understand.The Summer DoldrumsAfter all, traditional pop crooners seemed to be staging a comeback. Perry Como (of all people!) hit No. 1 with “Round and Round.” Pat Boone scored with the languid “Love Letters in the Sand.” Debby Reynolds had a hit with “Tammy.” Holy schlock, Batman, even Elvis seemed to be getting goo-goo eyed all of a sudden with “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear.”So, the question in ‘57: where were summertime’s rebels? That year the cool kids had already packed up their beach towel and gone on back to school by the time rock’s Next Big Wave hit:— Sept. 9, 1957, Buddy Holly and The Cricket, “That’ll Be the Day.”— Oct. 11, 1957, Everly Brothers, “Wake Up Little Susie.”— Oct. 21, 1957, Elvis, “Jailhouse Rock.”— Dec. 21, 1957, Danny and the Juniors, “At the Hop.”But even before that fall, diehards could dig a little deeper in the radio playlist for up-and-coming rockers. Jerry Lee Lewis was howling away with “A Whole Lot of Shakin’.” Fats Domino was still down there somewhere with “I’m Walkin’.” Jackie Wilson was right on deck with “Reet Petite.”About This Week’s SongAnd languishing even further down on the summer music charts — oh, somewhere around No. 24 or so — was the subject of this week’s podcast. It’s The Flood’s favorite souvenir from the Summer of ‘57: The Coasters’ wonderful “(When She Wants Good Lovin’) My Baby Comes to Me.”As reported here earlier, this winking and nodding Jerry Leiber-Mike Stoller composition was a minor hit for The Coasters. It did resurrect nine years later when a little known group called The Chicago Loop took it for a spin and got to No. 37 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.But in the Floodisphere, we much prefer a different pressing of the song released one year earlier. Favorite folksinger Tom Rush’s 1965 self-titled debut Elektra album included a version of the tune accompanied by bassist Bill Lee along with John Sebastian (of The Lovin’ Spoonful) and Fritz Richmond (of The Jim Kweskin Jug Band.)This track, captured at last week’s rehearsal, features the arrangement we’re working up to include on the new album when we start recording in the weeks ahead. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Fourteen years ago this week, The Flood had a wonderful evening with a local legend, a gentle soul named Mark Keen. Visiting from his Pittsburgh home, Mark sat in on harmonica for a rollicking evening of blues. Growing up in Huntington, Mark and a long-time Flood buddy, guitarist Randy Brown, went all through school together here back in the ‘70s. Mark didn’t get back to Huntington very often, but when he did, Randy brought him around to jam with The Flood on the evening of Nov. 9, 2011. The video above — shot by Flood manager Pamela Bowen — is a homage to that night.The Keen FamilyIt was one of Mark’s rare visits back to his hometown since his father’s death. Leonard Keen died in 2009 at age 94 after nearly 50 years of running a fixture on Huntington’s 9th Street, Keen Jewelers.Born in Cincinnati in 1914, Leonard served in the U.S. Navy and during the Great Depression worked for the federal Works Progress Administration.In a story in his “Lost Huntington” column in The Herald-Dispathc, local historian James E. Casto quoted Keen as saying, “My wife was a native of Huntington. So during a visit to her parents, we decided that Huntington would be a good place to open a store.”Keen and his wife Betty Ann moved from Louisville to Huntington and in April 1958, Mayor Harold Frankel helped cut the ribbon at their new store, which was located at 322 9th St. Exactly 20 years later, on April 16, 1978, after urban renewal forced the jewelry store to relocate, Frankel again did the honors, helping Keen cut the ribbon at a new location, just down the street at 419 9th St.Leonard and Betty’s son Mark was born in 1952 and grew up in Huntington, a talented drummer and harmonica player who performed with bands here and later in the Pittsburgh area.Mark’s PassingAfter The Flood’s delightful jam that November evening at the Bowen House, we never got to see Mark again. A half dozen years later, he passed away at 65 at home in Oakmont, Pa., of natural causes.Following a celebration of Mark, he was interred at Huntington’s Spring Hill Cemetery. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

From a thousand miles away, Matt Whyte has been a Flood fan for at least a decade and a half, but until recently he was never in the same room with the band.Instead, Matt always had to limit his Floodifying to singing along with the albums he received from his mom, JoAnn McCoy.But he was attentive to his studies. We know that because last week when he and JoAnn finally traveled from their Bradenton, Fla., homes to reach the Bowen House for his first in-person Flood encounter, Matt was so well-versed that he had specific requests for tunes he’d like to hear.Top of the ListHis favorite? Matt has a particular affinity for “Didn’t He Ramble?” a tune that he learned from the band’s 2011 Wade in the Water album. That rollicking century-old song relates the deeds and misadventures of a rambling ne’er-do-well named Buster: Mama raised three fine sons, Buster, Bill and me, Buster was the black sheep of our little family….The opening verse’s second couplet, though, is the one that most resonates with our young Matt: Mama tried to quit him of his rough and rowdy ways. She finally had to have the judge to give him 90 days!That struck a chord because nowadays it is Matt himself who often hands out such sentences. You see, back in Bradenton, JoAnn’s son is Judge Matthew Whyte for Florida’s 12th Judicial Circuit Court for DeSoto, Manatee and Sarasota counties.Matt’s Vocal ContributionMatt even has a favorite part of his favorite Flood tune. The second verse of “Didn’t He Ramble?” begins: He rambled into a swell hotel, his appetite was stout, But when he ‘fused to pay the bill, the landlord throwed him out.On the original Wade in the Water album cut, the late Dave Peyton underscored that moment with an emphatic “Get out!”“I laugh every time I come to that part,” Matt told us at last week’s rehearsal. So it was just natural that when we played his tune for him and we came to that spot, we let His Honor do the honors. You can hear the debut Matt Whyte Solo at 01:39 in this week’s podcast.A Family Tradition of FloodishnessAs noted, Matt Whyte’s Flood interests are a family tradition. Beginning in 2006, Matt’s mom, JoAnn, and her husband, the late Bob McCoy, were often in the room for the weekly Flood gatherings, sharing jokes and stories, smiling at our progress on their own favorite tunes.The pair was on hand for some important Flood events, from the debut of Jacob Scarr, the 14-year-old guitar savant whom we called “Youngblood,” to the beginning of the weekly Flood podcasts in 2008. One of the first podcast listeners was Bob when he and JoAnn returned to Florida that December. Sometimes he and JoAnn even challenged traffic regulations on their drives north, just to reach the room before the music started.No wonder JoAnn was eager to share her Flood love with her son Matt.About the SongWhen the great Charlie Poole and his North Carolina Ramblers recorded “Didn’t He Ramble?” in 1929, the song already was more than a quarter of a century old, with roots in the New Orleans of Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton.But, as we reported in Flood Watch a while back, the seeds of the song are planted even deeper than that. For instance, the song’s key lines (Didn’t he ramble? Didn’t he ramble? / Oh, he rambled till the butcher cut him down!) crop in a Texas work song that was published in 1888.For more on the song and its wild and rambling history, click here to read that old Flood Watch article.Meanwhile, 800 Songs Along Incidentally, this is the 800th episode of The Flood’s weekly podcast since it began 17 years ago next month.That means that the website now has more than 50 hours of free Flood music online, contributed at a rate of four or five minutes a week. Click the link below for details on those developments:Meanwhile, a few years ago, that deep, broad database of all those Flood tunes inspired us to roll out our most ambitious project to date. Radio Floodango, the free music streaming service, lets you listen to a continuous, randomly generated playlist of Flood tunes whenever/wherever you’d like. For more about that, check out this earlier article. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

It’s not easy to make the top dozen in CMT’s “100 Greatest Love Songs,” but that is precisely the placement that the music network awarded to Keith Whitley’s recording of “When You Say Nothing At All.”The song has a beloved place in our hearts. We remember the Christmas Eve in 1988 when that lovely number hit No. 1 in Billboard’s Hot Country Singles.And for many of us, that is the sweet tune that first came to mind just five months later in a much sadder moment: when we heard the shocking news that 34-year-old Whitley had died at his Goodlettsville, TN, home.One of UsThe news hit especially hard in our area. Keith Whitley was a local hero. Born in Ashland, he grew up in the nearby Sandy Hook, Ky.It seemed like every one of that town’s thousand residents knew Keith, but conversation was almost non-existent on the day of his passing. Words lost out to stunned silence.Today his memory is permanently etched into the landscape. A street is named “Keith Whitley Boulevard.” A memorial statue stands near the Elliot County Veterans Memorial and Cemetery. Peaceful, it is hallowed ground.Our Channelling KeithSome songs are like old friends. This old Paul Overstreet-Don Schlitz tune is certainly like that. We hadn’t played it in six months or more, and then one sultry night last August, it strolled back into the band room like it had never left. Danny Cox kicked off those familiar first chords. Randy Hamilton stepped up with the opening lyrics, and this was the result.For more about the history of how this song came into being, see this earlier Flood Watch article. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Often over the years, this tune has conjured up a very specific gig memory for Floodsters.It dates back to a weekend when the band was invited to the top of West Virginia’s Snowshoe Mountain to be part of a rather swank do (“a wine and cheese affair,” as the late Joe Dobbs liked to call such jobs).We were on a stage under a huge event tent on the grounds of Snowshoe ski resort in Pocahontas County. The summer evening breeze was sweet. The glasses were tinkling. Then, toward the end of the night, a jolly gypsy troupe of motorcyclists rolled and crashed the party.We didn’t know what would happen next. For a moment there, it looked to some of us like that edgy turning point in a Tarantino picture.But just as suddenly, the guys in leather and the guys in suits started mingling together, laughing, drinking, swapping stories. Deep in The Flood’s memory banks to this day are images of that eclectic crowd of bankers and bikers singing along as one on this song. “Ohhhhh, MAma! Ain’t you gonna miss you best friend nowww!”About the SongAs reported in an earlier Flood Watch article, Bob Dylan’s “Down in the Flood” was one of many songs that would fill the world’s first great bootleg albums, like the unforgettable Great White Wonder, which made the rounds from 1969 onward. (Nearly all those tracks later were officially released by Columbia Records as The Basement Tapes.)It turns out that “Down In The Flood” (also known as “Crash on the Levee”) evolved during a specific 1967 jam session at the Woodstock, NY, in the house that the guys dubbed “Big Pink.”As The Band’s Robbie Robertson remembers it, at that session Bob and the boys started fiddling with an old John Lee Hooker song called “Tupelo Blues,” about the historically devastating 1927 Mississippi River flood. That tune apparently triggered Dylan’s memories of another song, one from his repertoire in the early years, called “James Alley Blues,” based on a 1927 Richard “Rabbit” Brown recording. Significantly, that song uses the phrase “sugar for sugar, salt for salt,” a line that would find its way into Bob’s own lyric.For more on the song’s history, click here to read that earlier article.Our Latest Take on the TuneBob Dylan once famously spoke in another 1960s song about “a thousand telephones that don’t ring.” But that’s hardly a problem for us in our new millennium. On the contrary, we’re all walking around with phones in our pockets that are apt to sound off at the most inopportune moments. Like in the middle of this track from last week’s rehearsal when Sam St. Clair’s phone chimes in. But our Sam’s an especially cool lad, so you’d that expect even his phone’s ringtone would contribute something special. And it does. Wait for it: at 02:43, a nifty xylophone audition at mid-song!More Bobby? Step Right Up!The Flood does a lot of Bob Dylan tunes, of course. We even have a special playlist of them that we put together for a Dylan birthday observance a few years ago. Click below to read all about it. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

When Thomas A. Dorsey (a.k.a. “Georgia Tom”) walked out of a New York City recording studio in the winter of 1932, he ended a highly successful music partnership with Tampa Red (a.k.a. Hudson Whittaker).Over four years, Red and Tom garnered a happy following for their infectious, highly danceable brand of blues tunes.In 1928, the two young men had teamed up and recorded for the Paramount label the hit “Tight Like That.” The success of that number — based on Blind Blake’s “Too Tight” and on Papa Charlie Jackson’s “Shake That Thing” — inspired imitators and launched the blues genre known as “hokum,” as reported here earlier, Whittaker and Dorsey recorded more than 60 sides together, often under the name “The Famous Hokum Boy.” Some of these rollicking tunes have been covered by The Flood over the years, songs like “Somebody’s Been Using That Thing,” “Yas Yas Duck” and “You Can’t Get That Stuff No More.”And add to that list the last tune that Tom and Red ever recorded together. The composition they called “No Matter How She Done” was waxed on Feb. 3, 1932, and released that spring on Brunswick’s Vocalion label.Nothing in Red’s sassy lyrics hinted at an end to this lucrative collaboration: The copper brought her in, she didn’t need no bail She shook it for the judge, they put the cop in jail! As we noted in an earlier Flood Watch report, when Dorsey left the blues field in 1932 to take up a career as gospel songwriter and choir director, Whittaker continued as a solo blues artist well into the 1940s.Floodifying ItFlash forward seven decades. When The Flood started doing this song in the early 2000s, we committed what some folk purists consider a sacrilege: We altered both its title and its hook, removing one entire syllable. Instead of Tampa Red’s original “No matter how she done it” lyric, The Flood opted to sing “Any way she done it.”We’re still doing it that way, in fact, as you hear in this track from a recent rehearsal. And, no, we have no excuse, not really, except an aesthetic one. We felt the revision simply allowed the line to flow more easily off the tongue. (Call your neighborhood linguist and ask about the joys of removing “alveolar taps.”)One thing for sure: now, as then, the new phrasing does facilitate group singing, as you can hear on the band’s lively original rendering 20 years ago on our Plays Up a Storm album. Click the button below to hear it:That track, recorded on the evening of Nov. 16, 2002, featured Sam St. Clair, Joe Dobbs, Doug Chaffin, Chuck Romine, David Peyton and Charlie Bowen.The Bob Wills ConnectionWhile the tune (any way we sing it) has always had a happy hokum vibe, “No Matter How She Done” took a curious turn four years after Tampa Red and Georgia Tom’s inaugural recording.In September 1936 in Chicago, the song got a cool country treatment by no less a luminary than Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys.This was just three years after Wills organized the band in Waco, Texas, and set about defining the style of music that’s come to be known as “Texas swing.”Released as a single in May 1937, “No Matter How She Done It (She’s Just a Dirty Dame)” was recorded in Wills and the Playboys’ second major recording sessions for the American Record Corporation.The session is particularly important for Wills collectors, because it features the lineup that would define the Texas Playboys sound for years to come, including vocalist Tommy Duncan, pianist Al Stricklin, steel guitarist Leon McAuliffe and drummer Smoky Dacus.More Hokum, You Say?Meanwhile, if more hokum music is what you need to make your Flood Friday complete, remember that we’ve got a whole channel waiting for you on the free Radio Floodango music steaming service.Just drop in and click the “Hokum” button or, better yet, just use this link to jump to it directly. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com