Discover Voices of British Ballet

Voices of British Ballet

Voices of British Ballet

Author: Voices of British Ballet

Subscribed: 17Played: 195Subscribe

Share

© Voices of British Ballet

Description

Voices of British Ballet tells the story of dance in Britain through conversations with the people that built its history. Choreographers, dancers, designers, producers and composers describe their part in the development of the artform from the beginning of the twentieth century.

Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

56 Episodes

Reverse

Anne Heaton’s career coincided with an upsurge in creative talent at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. Observant and wide ranging she reflects on many things, not least the enigmatic choreographer, Andrée Howard. In this interview, which was recorded in 2003, she is talking to Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet. The interview is introduced by Monica Mason.Anne Heaton was born in Rawalpindi, India, in 1930. She studied with Janet Cranmore in Birmingham from 1937 until 1943, and then with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School. Her debut was with the Sadler’s Wells Opera in 1945 in a production of The Bartered Bride, and she became a soloist with Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet (SWTB) in 1946. That year, Heaton created roles in two ballets by Andrée Howard, Assembly Ball and Mardi Gras, and also in Celia Franca’s Khadra. In 1947, she created a role in Frederick Ashton’s Valses Nobles et sentimentales. She transferred to Sadler’s Wells Ballet at Covent Garden in 1948, where she specialised in romantic roles, for example, in Les Sylphides and Giselle. She performed again with SWTB when it was renamed The Royal Ballet Touring Company, creating the roles of the Woman in Kenneth MacMillan’s The Burrow in 1958 and the Wife in The Invitation in 1960. A foot injury caused her to resign from The Royal Ballet in 1959, but she continued to dance intermittently until 1962. Following her retirement from the stage, Heaton taught at the Arts Educational School and, from time to time, she staged ballets, including Giselle in Tehran in 1971. Having married Royal Ballet principal dancer John Field, who later became director of The Royal Ballet Touring Company, she co-directed the British Ballet Organization with him from 1984 until 1991. Field died in 1991 and Heaton in 2020. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

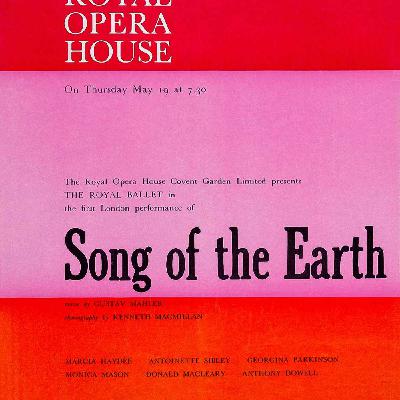

Darcey Bussell talks to the dance critic Alastair Macaulay about her graduation performance at The Royal Ballet School, her early career with both Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet and The Royal Ballet, and the creation in 1989 of the role of Princess Rose in Kenneth MacMillan’s The Prince of the Pagodas, as well as her experience of being coached by Margot Fonteyn. The interview, which was recorded in 2017, is introduced by Alastair Macaulay.Darcey Bussell was born in London in 1969. After initial vocational training at the Arts Educational School, she joined The Royal Ballet Lower School at the age of 13. In 1987 she graduated from The Royal Ballet Upper School and joined the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet that same year, but it was whilst still at the school that her talent had been noticed by the choreographer Kenneth MacMillan, who decided to create on her the leading role of Princes Rose in his new version of The Prince of the Pagodas. Bussell joined The Royal Ballet in 1988 and was promoted to the rank of principal dancer in 1989 on the opening night of MacMillan’s new ballet.During her distinguished career with The Royal Ballet, Bussell became one of the most famous British dancers of her time, and indeed of any time. She was particularly noted for her combination of a tall, athletic physique with a lovely soft lyricism. During her dancing career she performed in as many as 80 different ballets, including the majority of the classical roles, and had 17 new roles created on her. She stayed with The Royal Ballet until her formal retirement from the stage in 2007 (in a performance of MacMillan’s Song of the Earth), but she had also appeared as a guest artist with many major companies abroad, including New York City Ballet, the Ballet of La Scala, Milan, the Kirov Ballet, the Hamburg Ballet and The Australian Ballet.Even while dancing professionally, Bussell had begun to work in television and other media, and this side of her career developed at a fast pace on her retirement from ballet. As well as writing, modelling and presenting – both for television and for the Royal Opera House relays – she became a household name as a judge on the BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing (2009 to 2019). Since 2012, Bussell has been the President of the Royal Academy of Dance. Also in 2012, she danced the Spirit of the Flame at the Closing Ceremony of the London Olympic Games, leading a troupe of 200 dancers. She supports many educational and charitable causes, both artistic and in other fields. She has received many honours, including a gold medal from the John F Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and an honorary doctorate from Oxford University in 2009. Darcey Bussell was appointed an OBE for her services to dance in 1995, a CBE in 2006 and was made a DBE in 2018. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

In this extract, poor Henry Danton always seems to be running behind his talent – that is until he met the wonderful ballet teacher, Vera Volkova. However, before this and often against the odds, he managed to do quite a few things. From his early training with Judith Espinosa, he went on to work with Allied Ballet, International Ballet and, finally, Sadler’s Wells Ballet, and all this in the space of a few years. Candid and clear, something eventually went right as Henry continued to teach ballet into his 100th year. In this interview, recorded in 2004, Henry Danton talks to Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet. The interview is introduced by Alastair Macaulay.Handsome and dashing, clever and full of life and good humour, Henry Danton was born into an army family in Bedford in 1919. He was educated as a King’s cadet at Wellington College. At first, Danton joined the army, but when on sick leave, following a back injury, he was introduced by a friend to the ballet teaching of Judith Espinosa. Almost overnight a new life unfolded for him. Although an avid ice skater, ballet had not been contemplated, but was “in his bones”, so to speak. After only 18 months of training, Danton joined the short-lived Allied Ballet, and then Mona Inglesby’s International Ballet. He joined the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 1944. Here he began studying with Vera Volkova in her West Street Studio, and his lifelong passion and interest in Russian ballet training began. Volkova helped him to understand and fill in the gaps in his training. He was one of the original six dancers in Frederick Ashton’s Symphonic Variations at Covent Garden in 1946. From here he danced with various companies, including Les Ballets des Champs-Elysées, and toured the United States of America with Roland Petit’s Ballets de Paris. The USA became his home. He taught and choreographed extensively, both there and internationally, and was teaching at The Dance Studio with the Ballet Theatre of Scranton, Pennsylvania, until shortly before his death in 2022.The photograph shows Henry with Julia Farron and Gillian Lynne rehearsing a studio revival of Miracle in the Gorbals at White Lodge in 2011 photo courtesy of Marius Arnold Clarke Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Jean Bedells talks about the 1930s as if it was yesterday. Full of detail and feats of memory, we are given an idea of the sense of foreboding that descended when their artistic home, Sadler’s Wells, was taken over as a refugee centre at the start of World War Two. In this interview, which was recorded in 2005, Jean Bedells talks to former Royal Ballet principal dancer Bruce Sansom. The interview is introduced by Alastair Macaulay.Jean Bedells was born in Bristol in 1924 as Jean McBain. She was the daughter of Phyllis Bedells, the great British ballerina, teacher and, later, a founding member and examiner for the Royal Academy of Dance. Jean Bedells first studied ballet with her mother and then trained at the Vic-Wells Ballet School for a year in 1936 before joining the Vic-Wells Ballet in 1937, making her debut as Clara in The Nutcracker. She had leave of absence from the company to dance as the Herald of Spring in Hiawatha at the Royal Albert Hall in 1937, 1938 and 1939. When she rejoined the Vic-Wells Ballet in 1938 she danced in Les Patineurs and The Haunted Ballroom, as Rose and Silver Fairies in The Sleeping Princess [The Sleeping Beauty], as Bathilde in Giselle, and in The Quest and, later, as one of the Three Fates in Adam Zero. She also appeared in a number of early films made of the company, notably as the Fairy Silver in The Sleeping Princess (1939), a Red Pawn in Checkmate (1939) and, later, a character role in a film of The Nutcracker (1958).In 1946, Jean Bedells became ballet mistress for Sadler’s Wells Ballet when the company moved into the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden. (The Vic-Wells Ballet was re-named Sadler’s Wells Ballet in the early 1940s.) She became a teacher after her retirement from the company, often teaching at The Royal Ballet School, especially during the 1960s and 1970s. Her granddaughter, Anne Bedells, was a member of London Festival Ballet. Jean Bedells died in 2014. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Dianne Richards talks about skipping her dancing life, especially the start of London Festival (now English National) Ballet. Names from the world of Serge Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes, such as Alexandra Danilova, as well as Tamara Toumanova, Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin, weave through her very special company story and still cast a shimmering magic spell whenever mentioned.In conversation with Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, Dianne explains how, at the age of 14, she danced in a performance in her native Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), in which Markova and Dolin were appearing as guest artists. When she was 16, Dianne came to England with her mother. Dolin remembered her and asked her to join London Festival Ballet (LFB), with whom she worked for 18 years. Dianne was soon dancing solos and was coached in the role of The Nutcracker’s Sugar Plum Fairy by Markova herself. With LFB Dianne toured the world, including long tours of North America where the company had their own train. A highlight was performing in Monte Carlo in 1956 for the wedding of Grace Kelly and Prince Rainier; another was Igor Stravinsky conducting Petrushka in Chicago and disagreeing with Dolin over tempi. She also recalls Charlie Chaplin pursuing Nathalie Krassovska in Paris. The interview is introduced by Deborah Weiss.Born in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) in 1934, Dianne Richards studied under Majorie Sterman. She joined London Festival Ballet in 1951, becoming a soloist in 1955 and a principal in 1959. In a very full career with the company, she toured the world and worked with many famous dancers, including Alicia Markova, John Gilpin, Anton Dolin, Erik Bruhn, Serge Lifar, Alexandra Danilova, Tamara Karsavina, Irina Baronova and Tamara Toumanova. She also appeared as a guest artist with American Ballet Theatre from 1963 to 1964. Richards danced with Galina Samsova and Andre Prokovsky’s New London Ballet in 1972 and then with Scottish Theatre Ballet until 1974, when, at the age of 40, she retired from the stage. She then went to live in South Africa, and in her retirement taught from time to time, including at a newly opened academy in Hong Kong and, at the invitation of Robert de Warren, for Northern Ballet Theatre in England. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

The distinguished choreographer and director Richard Alston explains to Alastair Macaulay, how, as a teenager, he was entranced by watching ballet. After studying fine art, he began working on the Martha Graham technique with what became the London Contemporary Dance Theatre. He eventually found this too restricting and embraced the freer, less floor fixated approach of contemporary dance associated with Merce Cunningham. Alston goes on to discuss how his own choreography began, and how it developed in line with this expansion of his aesthetic. He speaks about his dealings with Cunningham and with the composer John Cage and also about his long and immensely fruitful creative partnership with Sue (Siobhan) Davies. The interview is also introduced by Alastair Macaulay.Richard Alston was born in October 1948 in Sussex. He is a British choreographer as well as having been artistic director for several dance companies. His education began at Eton College, followed by two years at Croydon School of Art. His passion for ballet was first sparked after attending performances by the Bolshoi Ballet and The Royal Ballet Touring Company, and also by Merce Cunningham and the Martha Graham Dance Company, which excited an interest in modern dance. As a result, he started attending classes with the Rambert School of Ballet, and in 1968 he became one of the London Contemporary Dance Theatre’s original students. After only three months there, he created his first work, Transit. In his third year at the School he organised a group of students to tour schools, colleges and universities demonstrating the Graham technique. After choreographing for London Contemporary Dance Theatre, he created an independent dance company, Strider, in 1972.In 1975, Alston travelled to New York to study primarily with Merce Cunningham at the Merce Cunningham Dance Studio. He returned to Europe two years later, working as an independent choreographer and teacher. In 1980, he was appointed resident choreographer for Ballet Rambert. He founded Second Stride with Siobhan Davies and Ian Spink in 1982, and in 1986 was appointed artistic director of Ballet Rambert, a post he held until 1992. To reflect the changing nature of the company and its work, in 1987 Ballet Rambert changed its name to become Rambert Dance Company. During his years with Rambert, Alston created 25 works for the company, as well as pieces for the Royal Danish Ballet and The Royal Ballet.After working in France and at the Aldeburgh Festival, in 1994 Alston became artistic director of The Place and he also formed Richard Alston Dance Company. A steady stream of over 50 dance works created by Alston over the next decades was interspersed with collaborations with the London Sinfonietta and Harrison Birtwistle in 1996, and several television productions, including The Rite of Spring, commissioned by the BBC for their Masterworks series in 2002. The Richard Alston Dance Company celebrated its tenth year with its first appearance in New York in 2004. In 2006 the company made its first full tour of North America, followed by further tours in 2009 and 2010. Alston created a new ballet, En Pointe, A Rugged Flourish, for New York Theatre Ballet in 2011. In March 2020, the Richard Alston Dance Company was wound up after a quarter of a century of critical acclaim., giving its last performance at Sadler’s Wells. Richard Alston received the De Valois Award for Outstanding Achievement in Dance at the Critics’ Circle National Dance Awards in 2009. He was appointed a CBE for services to dance in 2001, and was knighted in 2019. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Over a long career, Edward Watson became one of The Royal Ballet’s greatest male principals, in the footsteps of Anthony Dowell and David Wall. He is particularly noted for his work in the ballets of Frederick Ashton and Kenneth MacMillan, and for creating many roles with contemporary choreographers. Here, in a conversation with Jane Burn recorded for Voices of British Ballet in 2007, he speaks disarmingly about his early days in The Royal Ballet before sharing some insights about portraying Crown Prince Rudolf in MacMillan’s Mayerling, a role for which he is particularly associated. The interview is introduced by Kenneth Olumuyiwa Tharp.Edward Watson was born in South London in 1976, and trained at The Royal Ballet School, first at the Lower School at White Lodge, and then at the Upper School in Barons Court. He graduated into The Royal Ballet in 1994 and was promoted to the rank of principal dancer in 2005. Watson’s pure classical technique, combined with a fine dramatic flair and sensitivity served him well in the works of Frederick Ashton, Kenneth MacMillan and Ninette de Valois herself, choreographers at the heart of the British tradition. He has himself been a major force in the continuation of that tradition. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

This episode is introduced by Dame Monica Mason. Violetta Elvin was one of Frederick Ashton’s favourite ballerinas. She was born Violetta Prokhorova in Russia. Here, in this interview with Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, Violetta traces her evacuation to Tashkent at the start of World War II and how she returned, via Kuibyshev, to Moscow to join the Bolshoi Ballet. Despite being warned by the authorities not to talk to foreigners, she married the British diplomat Harold Elvin and managed to come to London in 1946. Only weeks after her arrival she joined the Sadler’s Wells Ballet at Covent Garden and danced the “Blue Bird” pas de deux on the second night of their opening production of The Sleeping Beauty. The interview is introduced by Monica Mason.A dancer of rare beauty, Violetta Prokhorova was born in 1923. She trained at the Bolshoi Ballet School in Moscow and joined the Bolshoi Ballet in 1942, following her graduation performance, for which she was coached by Galina Ulanova. When Moscow was evacuated and the Bolshoi was scattered, she danced as a ballerina with the State Theatre of Tashkent. In 1944 she re-joined the Bolshoi in Kuibyshev, on the Volga, where she fell in love with a young Englishman, Harold Elvin. The Bolshoi returned to Moscow in early 1945. She danced with the Stanislavsky Ballet for a year, then married Elvin and obtained permission from Joseph Stalin to leave Russia.Once in London Violetta started training with Vera Volkova, where she was seen by Ninette de Valois and immediately offered a place in the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. She adored and was true to her Russian training, but with her intelligence and sensitivity she was able to fit in beautifully with the British repertoire. From the Black Queen in de Valois’ Checkmate, through all the classical ballerina roles to Roland Petit’s Ballabile in 1950, Violetta Elvin as she was now known, danced with exquisite vivacity, a hint of exoticism and always impeccable port de bras. Frederick Ashton created several roles for her, notably the Summer Fairy in Cinderella (1948), Lykanion in Daphnis and Chlöe (1951), and one of the seven ballerinas in Birthday Offering (1956). For a decade Violetta Elvin was a unique and irreplaceable member of the developing Sadler’s Wells Ballet. She went to live in Italy in 1956, and although she guested with several companies, including La Scala, Milan (where she performed alongside soprano Maria Callas) in 1952 and 1953, and briefly directed the Ballet of the Teatro San Carlo in Naples in 1985, she retired from ballet when her heart called her elsewhere. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

David Vaughan – unparalleled writer on the choreography of Frederick Ashton – catches moments and movements from The Royal Ballet’s history. In this interview for Voices of British Ballet, which was recorded in New York, he talks to his friend and fellow dance writer Alastair Macaulay. The episode is also introduced by Alastair Macaulay.The archivist, historian and critic David Vaughan was born in London in 1924. He studied at Oxford University and only began dance training after that, in 1947. In 1950 he won a scholarship to study at the School of American Ballet, where he met Merce Cunningham, who was teaching there. Vaughan began studying with Cunningham from the mid 1950s. Later, in 1959, when Cunningham opened his own studio, Vaughan began performing various tasks for Cunningham and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, including co-ordinating the company’s six-month tour of Europe (with John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg) in 1964. Vaughan became the company’s official archivist in 1976, a post he held until 2012, when the company was disbanded following Cunningham’s death.In addition to writing and working for and with Cunningham, Vaughan was active in the theatre, film and dance worlds. He acted in off-Broadway productions, devised the choreography for Stanley Kubrick’s film Killer Kiss, and worked on the scripts for films about Cunningham and Cage, and about the choreographer Antony Tudor. Vaughan also appeared in several dance productions, including The Royal Ballet’s revival of Frederick Ashton’s A Wedding Bouquet. In 1988 he wrote an influential op-ed piece in The New York Times, criticising traditional ballet companies for not offering dancers of colour enough opportunities to perform.David Vaughan was a prolific and well-regarded writer on ballet and dance. His books included The Royal Ballet at Covent Garden (1976), Frederick Ashton and His Ballets (1977, revised edition 1999) and Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years (1996). He contributed frequently to the Dancing Times magazine, and with Mary Clarke he also edited and contributed to The Encyclopaedia of Ballet and Dance (1980). In 2015 David Vaughan received a Dance Magazine award. He died in New York City in 2017. Photograph courtesy of The Merce Cunningham Foundation Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

In this no-nonsense, down-to-earth account of writing music for Northern Ballet Theatre’s production of Aladdin, choreographed by Laverne Meyer in 1974, composer Ernest Tomlinson talks to Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet. The interview is introduced by Stephen Johnson.Ernest Tomlinson was a British composer, well known for his contributions to light music and for founding The Library of Light Orchestral Music (which prevented the loss of 50,000 works released from the BBC’s archive and other collections). He wrote the music for the ballet Aladdin for Northern Ballet Theatre in 1974.Tomlinson was born in 1924, in Rawtenstall, Lancashire. His parents were musical, and he sang as a chorister at Manchester Cathedral. After a grammar school education, he studied at Manchester University and the Royal Manchester School of Music, with a break for war service in the RAF. He moved to London after graduation in 1947, working first for music publishers. In 1955, after some of his compositions had been performed by the BBC, he formed his own orchestra – the Ernest Tomlinson Light Orchestra – and set out on a highly successful freelance career as a prolific composer, conductor and director of choirs and orchestras. He was particularly concerned to counter the notion of a strict division between art music and popular music. His own Sinfonia 62 was written for jazz band and symphony orchestra, while his Symphony 65 was performed at festivals in London and Munich and in the Soviet Union in 1966, where it was the first symphonic jazz to be heard there. In 1975, Tomlinson won his second Ivor Novello Award for his ballet, Aladdin. Among many other professional appointments, he was the chairman of the Light Music Society from 1966 until 2009. Ernest Tomlinson was appointed an MBE for his services to music in 2012. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Here is Patrick Harding-Irmer proving that it is never too late to start dancing. He says, in this interview with Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, he only began to take dance classes at the age of 24 but was soon working in dance commercially. In 1972, inspired by a visit to Australia by Nederlands Dans Theater, he came to Europe, where he fell under the spell of the Martha Graham technique and the teaching of Robert Cohan at London Contemporary Dance Theatre (LCDT). After nine months performing with the X Group, he joined the main LCDT, going on the be voted Best Contemporary Dancer in Europe in 1985. This interview was recorded in Sydney, Australia, in 2006 and is introduced by Kenneth Olumuyiwa Tharp.Patrick Harding-Irmer was born in Munich in 1945, where his Australian mother had been working in dance and choreography. After World War Two, she and he returned to Australia. In 1964 he represented Australia in the World Surfing Championships, and then began to study arts at Sydney University. At the age of 24 he began to take dance classes and to dance commercially. In 1972, inspired by a performance by Nederlands Dans Theater on tour in Australia, he travelled to Europe and began studying at London Contemporary Dance School, specialising in Martha Graham technique. That same year he joined the X Group of the London Contemporary Dance Theatre (LCDT), which included five dancers who toured the UK and abroad, demonstrating and teaching Graham technique. In 1973, after nine months with the X Group, Harding-Irmer joined the main company of LCDT. In 1985 he was voted Best Contemporary Dancer in Europe. He returned to Australia in 1990, and has subsequently taught, and also worked with Australian Dance Artists, a group of mature performers dancing their own creations in different settings. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

In April 2017, Marcia Haydée was in Stuttgart for a week to celebrate her 80th birthday. Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, knew this was her only opportunity to see Haydée in Europe, so she telephoned Stuttgart Ballet to see if she could interview her. Patricia takes up the story in her own words: “They listened to my request, and, in perfect English, said they would ask Miss Haydée. With a full schedule of rehearsals all week, Marcia said she was free on Thursday from 3.30pm to 4.30pm. She didn’t know me at all, but it was enough for her to know how much I loved Kenneth MacMillan’s ballet, Song of the Earth. So, I jumped on a plane…This is the extraordinary Marcia Haydée…”In the interview Haydée explains how she was aware of both John Cranko and Kenneth MacMillan as a student at the Sadler’s Wells (now Royal) Ballet School, without suspecting her later close involvement with both men. In working with them, Cranko came to appreciate her melding of a Russian and a British approach to dancing; MacMillan was demanding and uncompromising, but she always strove to fulfil his requirements. She speaks revealingly about working in Stuttgart with Cranko on Onegin and with MacMillan on Song of the Earth and suggests that in those days and in those works, dancers took things at a speed and with risks that today’s dancers, for all their qualities, do not attempt to emulate. The interview is introduced by Dame Monica Mason.Marcia Haydée is a Brazilian-born ballerina, choreographer and company director. She was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1937, and after studying in Brazil, came to the Sadler’s Wells (now Royal) Ballet School in London in 1954, joining the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas in Monaco in 1957. Haydée joined the Stuttgart Ballet in 1961 and was named prima ballerina the following year by the company’s director and choreographer, John Cranko. Their relationship – her dancing, his choreography – was to become the foundation of Stuttgart Ballet’s international reputation in works such as Onegin, Romeo and Juliet and The Taming of the Shrew, among many others. She also worked closely withKenneth MacMillan on works such as Las Hermanas, Miss Julie and, above all, his Song of the Earth and Requiem. In 1976, she became director of the Stuttgart Ballet, a position she held until 1996. During her dancing career she performed as a guest artist for notable ballet companies throughout the world. From 1992 until 1996 Haydée directed the Ballet de Santiago de Chile, and again from 2003 until 2004. Since retiring from performing she has pursued a career as a choreographer, teacher and coach, and she also stages many ballets.The episode photograph shows John Cranko in rehearsal with Marcia Haydée and Bernd Berg, 1962.

Photo: Hannes Kilian, courtesy Stuttgart Ballet Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Deborah MacMillan, who talks to former Royal Ballet principal Bruce Sansom, is not afraid to speak her mind. Here she variously both endorses and explodes myths. Apart from anything else, these ten minutes should give hope to anyone who suffers from depression – nothing is impossible. Through the gloom of life, both within and without, her husband, the choreographer Kenneth MacMillan, went on creating ballets that have given thousands of dancers around the world endless challenges and insights, let alone audiences. For all his breaking of moulds and pushing at frontiers, MacMillan’s absolute belief in the traditions of classical ballet is never far away. As well as being a choreographer, MacMillan was also director of The Royal Ballet from 1970 until 1977.The interview is introduced by Jennifer Jackson.Deborah MacMillan is the custodian of the ballets choreographed by her late husband, Sir Kenneth MacMillan, supervising productions of his works all over the world. Deborah Williams, as she then was, was born in Queensland, Australia, in 1944, and educated in Sydney. She studied paining and sculpture at the National Art School before moving to London in 1970, marrying Kenneth in 1974. She has designed ballets for both stage and television, as well as making numerous contributions to Royal Ballet productions, including the production realisation for the major revival of Anastasia in 1996, production and setting for a condensed version of Isadora in 2009 and costume designer for a revival of Triad in 2001. In 1984, Deborah returned to painting full-time and her work is represented in private collections both in the UK and the USA.From 1993 until 1996, Deborah was a member of the Royal Opera House Board, and in 1996 was chair of The Friends of Covent Garden. She has served as a member of the Arts Council of England from 1996 until 1998, when she chaired the dance panel. She has also been a trustee of American Ballet Theatre and a member of the National Committee of Houston Ballet. She became Lady MacMillan when her husband was knighted for his services to dance in 1983 Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Romayne Grigorova has had a long, distinguished career in ballet and the theatre. Here, in conversation with Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, she focuses on her early years, much of which was coloured by World War Two. In 1943, after training at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School, she worked with the Sadler’s Wells Opera on The Bartered Bride in London during the Blitz and on tour. In 1945 she travelled to Germany with the opera under the auspices of ENSA. She then joined Ballet Rambert, and went to Germany again, to Berlin, where she delivered food parcels to a German singer and her family in the Russian zone, and scissors to Lotte Reiniger, a famous German film director and pioneer of silhouette animation. Romayne Grigorova also speaks of her dealings with Marie Rambert and Andrée Howard, joining Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet in 1951 and touring to North America.The interview was recorded in 2003, and is introduced by Monica Mason who spoke to Natalie Steed before Romayne's death in July 2025.Romayne Grigorova was born in Sandwich, Kent, in 1927. She studied under Vera Volkova, Ninette de Valois, George Goncharov and Ailne Philips. Her first appearance on the professional stage was in 1942. In 1943, after training at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School for a further year, she danced in ballets with the Sadler’s Wells Opera in this country and, in 1945, on tour in Germany under ENSA. She joined Ballet Rambert in 1946 and then danced with the Anglo-Polish and Metropolitan Ballets until 1947, when the latter folded.Grigorova then worked in the commercial theatre until 1951, including performing in three pantomimes, before joining Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet, where she remained until 1955. She was ballet mistress for the stage musical Can-Can in 1955, and for the St Gallen Ballet in 1956. In 1957 she became ballet mistress for the Opera Ballet at the Royal Opera House, for whom she choreographed many ballets. She retired from this post in 1992 but continued to teach on a freelance basis. She performed small character roles with The Royal Ballet at Covent Garden, many of which had been created for her, such as Lady Montague in Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet and The Housekeeper in Peter Wright’s The Nutcracker. Romayne Grigorova was appointed an MBE for her services to dance in 2017. She died in July 2025.Photo by Donald Southern courtesy of The Royal Ballet Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

When Cassa Pancho decided to interview Black female ballet dancers in the UK for her degree dissertation in 1999, she could not find any. So she seized the moment, setting out on the path that was to lead, in 2001, to the company known as Ballet Black and its associated schools. Here, the indomitable Cassa talks to Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, about the early days of her career, her expectations for the company and the schools, the misunderstandings she has had to overcome and, above all, her insistence that at all levels the now highly acclaimed Ballet Black is a balletic enterprise, with all that entails in terms of standards. The interview, was recorded in 2010 and is introduced by Kenneth Olumuyiwa Tharp.Cassa Pancho was born in London in 1978, to Trinidadian and British parents. Her original ambition was to become a ballerina. She trained at the Royal Academy of Dance and in 1999 gained her degree from Durham University.In 2001, at the age of 21, she founded Ballet Black in order to promote diversity in ballet and to increase the number of Black and Asian dancers in mainstream ballet companies.She has built a distinct and unique repertoire for her company from a wide range of distinguished choreographers. Ballet Black tours extensively, both in the UK and abroad, with regular London seasons at venues such as the Barbican Theatre and the Linbury Theatre of the Royal Ballet and Opera. Cassa realised from the start the importance of building for the future, and in 2002 set up the Ballet Black Junior School in Shepherd’s Bush, as well as an associate programme for younger pupils. She oversees the programme for young dancers, and teaches regularly herself.In 2009 Cassa Pancho graduated from the National Theatre Leadership programme. Also in 2009 Ballet Black won the Critics’ Circle National Dance Award for Outstanding Company, and the award for the Best Independent Company in 2012. She was appointed an MBE in 2013 for services to the Arts and was given the Freedom of the City of London in 2018. She is a Patron of Central School of Ballet and a Vice President of the London Ballet Circle.Photo: Ballet Black rehearsals Cassa Pancho [Artistic Director]; at the Fonteyn Studio, Royal Opera House, London, UK; 19 November 2006; Credit: Bill Cooper / ArenaPAL Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Stephen Johnson and Patricia Linton spoke to Yvonne Minton in 2017 about her role as a young member of The Royal Opera, singing Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde for The Royal Ballet in 1966. Her memories about that, and about the questions which were raised at the time, were crystal clear. She also has some wonderful reminiscences of life in the Royal Opera House at the time, including a bird’s-eye view of the great Maestro Georg Solti. At the end there is a gentle reminder that change is not always easy – in any profession. The interview is introduced by Stephen Johnson.The singer Yvonne Minton was born in Sydney, Australia in 1938. Having studied and performed in Australia, she came to London in 1961 to pursue her studies and career. By 1966, having become a regular member of the company of the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden, she sang in Gustav Mahler’s Song of the Earth for The Royal Ballet. She created the role of Thea in Michael Tippett’s opera The Knot Garden in 1970. She appeared in a variety of roles in most of the major opera houses in Europe, including Bayreuth, Salzburg and Paris, and at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. She made concert appearances with many of the best orchestras in the world and was particularly noted for her work with Georg Solti, with whom she made many recordings. In 1980, after a decade or more of prestigious international work, she was appointed CBE for services to music. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

In 1969, Peter Darrell choreographed Beauty and the Beast for Scottish Theatre Ballet. Here Thea Musgrave discusses with Stephen Johnson the challenges and idiosyncrasies she found when creating the music. She was amused to discover that she wasn’t the first composer to have to succumb to balletic demands! Deep, observant and fiercely straightforward, it is fascinating to hear Musgrave describe so poetically another work she created for dance, Orfeo. The interview is introduced by Stephen Johnson.Thea Musgrave is one of the United Kingdom’s most important and prolific contemporary composers, pursuing her own idiom and musical sensibility throughout a long and distinguished career. She was born in Barnton, in Edinburgh, and went to school in Shropshire. After study at the University of Edinburgh, from 1950 until 1954 she studied in Paris, working under the direction of the redoubtable and influential Nadia Boulanger. She attended the Tanglewood Festival (in Massachusetts) in 1958, studying under Aaron Copeland.In the late 1950s and 1960s she established herself in London as a notable figure in British musical life. In 1970 she was a guest professor at the University of California (Santa Barbara). In 1972 she married the American musician Peter Mark and has lived in the United States of America ever since, where she has held many notable positions, including a distinguished professorship at City University, New York, from 1987 until 2002.Musgrave’s style has been described as a synthesis of expression and abstraction, noted for its drama and complexity, often with a strong romantic undercurrent. Her many works include several operas, including ones devoted to Mary Queen of Scots, the abolitionist and social activist Harriet Tubman and the statesman Simón Bolívar, as well as many concerti and orchestral works, often inspired by poetic and pictorial themes. As well as working in America, she has made frequent visits to the United Kingdom and Europe, including taking part in the BBC’s ‘total immersion’ weekend devoted to her works in London in 2014. She composed the scores for two ballets, Beauty and the Beast in 1969 and Orfeo in 1975. Thea Musgrave has received many honours, including two Guggenheim Fellowships and many honorary degrees. She was awarded a CBE for services to music in 2002. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

This ‘voice’ of British Ballet is that of Pamela May. She was born in 1917 and after retiring as a ballerina with The Royal Ballet became the teacher par excellence for generations of Royal Ballet School dancers. May, interviewed by Patricia Linton, starts this clip by describing being a student herself in 1932 and watching Adeline Genée, the great Danish ballerina, and also the first President of the Royal Academy of Dance, perform a minuet with Anton Dolin on tour in Copenhagen. The interview is introduced by the writer and critic Alastair Macaulay who gives a wonderful context and explains how Ninette de Valois became known as "Madam."Pamela (Doris) May was born in San Fernando, Trinidad in 1917, where her father was an oil engineer. The family returned to England in 1921. She first studied ballet with Freda Grant, and later in Paris with Olga Preobrajenska, Lubov Egorova and Mathilde Kschessinska. She joined the Vic-Wells Ballet School in 1933 and made her debut with the Vic-Wells Ballet in the pas de trois from Swan Lake in 1934.May became a principal with company and danced the whole gamut of the repertoire, including creating many roles, until she retired from dancing ballerina roles in 1952. She then became a leading mime and character artist and stayed with what became known as The Royal Ballet in this capacity until 1982. All this happened alongside her teaching at The Royal Ballet School from 1954 until 1977. Pamela May was appointed OBE for services to dance in 1977. She died in 2005. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

A conversation Mary Clarke, former editor of Dancing Times. It is thanks to her godson, Jerome Monahan, that we have this evocative and informative interview with Mary Clarke. Writer extraordinaire on all aspects of ballet, she hated the sound of her own voice and even more the look of her transcript. In these few minutes, however, she manages to convey the feeling of several eras, and of many people and happenings. She also explains, in her low-key erudite way, how the word ‘balletomane’ entered the English language. Mary is interviewed by her friend, the former Royal Ballet soloist Meryl Chappell, and the interview is introduced by Jonathan Gray, former editor of Dancing Times, who worked closely with Mary during her later years.Mary Clarke was the dance historian and writer par excellence. Her two books on the birth of British ballet in the 20th Century - The Sadler’s Wells Ballet: A History and Appreciation (London, 1955) and Dancers of Mercury: The Story of Ballet Rambert (London, 1962) - remain the starting point for all future historians of ballet in the UK.Mary Clarke was born in London in 1923. After her schooling at Mary Datchelor School, she worked as a typist at Reuter’s Press Agency. She was a youthful enthusiast for ballet and all things theatrical, and her career as a ballet critic and journalist began in 1943 with her first published article (prophetically for Dancing Times) and with her appointment in the same year as London correspondent for the American Dance Magazine. After the end of the war Clarke wrote for the London-based Ballet Today magazine. From the mid-1950s until 1970 she was also the London correspondent for Dance News, another American publication, which was then run by the distinguished critic and writer Anatole Chujoy. In 1954 Clarke became the assistant editor of Dancing Times, first under Philip Richardson and then for Arthur Franks. On Franks’ sudden death in 1963, Clarke became editor of Dancing Times, a post she held until her retirement in 2010. For over half a century she chronicled the changing trends in ballet and dance worldwide and their effects with impeccable judgement and an encyclopaedic knowledge.Clarke was dance critic for The Guardian newspaper from 1977 to 1994 and associate editor (with Arnold L Haskell) for many years of the Ballet Annual. She co-authored a range of books with the ballet critic and writer, Clement Crisp, notably Ballet: An Illustrated History (London, 1973) and The Encyclopaedia of Dance and Ballet (London, 1977) with David Vaughan. Her quiet demeanour and straightforward style belied deep thought and high ambition for the art. Her contributions to A Dictionary of Modern Ballet (London, 1959) are awe-inspiring in their clarity and humanity, qualities rare in a critic. She was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Award of the Royal Academy of Dance in 1990, Poland’s Nijinsky Medal in 1996, and she was made a Knight of the Order of Dannebrog in 1992. Mary Clarke died in 2015. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

In this podcast, the dancer and teacher Leo Kersley discusses his formative years in London in the 1930s and the many different companies he eventually worked with during the Second World War, including a stint at the Windmill Theatre. Talking to Patricia Linton, director of Voices of British Ballet, he also mentions how, as a conscientious objector, he was briefly imprisoned at the start of the war. The interview is introduced by Jane Pritchard.Leo Kersley was born in poverty in Hertfordshire in 1920. His family having moved to London, he studied dance under a number of teachers, including Marie Rambert at the Mercury Theatre in 1934, dancing professionally from time to time. He was a soloist in Ballet Rambert from 1936 to 1939, and in 1939 worked for the Ballet Trois Arts.On the outbreak of World War Two in 1939, he registered as a conscientious objector and was briefly imprisoned. On his release, during 1940 and 1941 he combined his work in a hospital with dancing for Rambert in the evenings alongside his first wife, Celia Franca. He was a member of Sadler’s Wells Ballet from 1941-1942, and then the International Ballet. He was a member of the Anglo-Polish Ballet from 1942-1943. From 1945 until 1951 Kersley performed with Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet. In 1952, Kersley went to teach in Denver, Colorado, and in 1953 to Rotterdam in The Netherlands. Whilst there he danced with a number of companies but returned to England in 1959 to set up his own school in Harlow, which he ran until his second wife, Janet Sinclair. With Sinclair, who died in 1999, he published the well-regarded Dictionary of Ballet Terms in 1952. PhotoAnne Heaton (as A Serving maid), Leo Kersley (as A Shepherd) in THE GODS GO A'BEGGING; Sadler's Wells Opera Ballet; at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London UK 1946;Credit : Frank Sharman / Royal Opera House / ArenaPAL.com Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.