Discover Emergency Medicine Mnemonics

Emergency Medicine Mnemonics

Emergency Medicine Mnemonics

Author: Aaron Tjomsland

Subscribed: 19Played: 116Subscribe

Share

© Aaron Tjomsland

Description

Most podcasts are about understanding. This emergency medicine podcast is about knowledge recall. Active learning requires your brain to process actively.

Can you withstand sitting with the discomfort of being asked a question until you can answer it easily and readily?

I promise you won’t be comfortable listening to each episode, but after you withstand the discomfort, your ability to recall, will be far superior than any other passive, listening.

Can you withstand sitting with the discomfort of being asked a question until you can answer it easily and readily?

I promise you won’t be comfortable listening to each episode, but after you withstand the discomfort, your ability to recall, will be far superior than any other passive, listening.

63 Episodes

Reverse

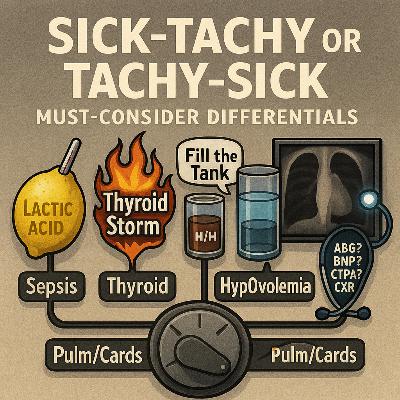

When the heart rate blasts past 150, our reflex is often to grab a syringe—diltiazem, metoprolol, something to slow things down. But here’s the hard truth: if the patient is in sick-tachy—tachycardia as a secondary compensation—slamming them with rate control can be catastrophic. That racing heart rate may be the only thing keeping them alive. Pausing to ask “sick-tachy or tachy-sick?” is what separates the new learner from the confident emergency clinician.This episode is all about STOP-ping before you treat the number. STOP is your mnemonic for the must-consider secondary compensations that drive tachycardia in the ED. Each of these can mimic or mask primary arrhythmias, and missing them can lead to disaster:⸻🛑 STOP MnemonicS – Sepsis • Tachycardia is often the earliest sign of infection. • Always check a lactate—“Lactic Acid” should be etched in your mind. • Bundle: fluids + source control. • Be cautious in elderly or vague abdominal presentations; tachycardia may be your only clue.T – Thyroid Storm • Look for agitation, fever, tremor, weight loss history. • Order TSH/T3/T4. • Treatment anchor: Beta-blockers (BB) are first-line for rate control here—unique compared to other scenarios. • Missing thyroid storm means missing a reversible cause of near-fatal tachycardia.O – HypOvolemia • Think bleeding (low H/H), dehydration, or anemia. • Visual: half water / half blood glass—“Fill the Tank.” • Don’t just reach for meds—give fluids, transfuse, and stabilize volume first. • Remember also anxiety/pain can amplify sympathetic tone.P – Pulm/Cards (Cardiopulmonary) • Pneumonia – fever, infiltrate, hypoxia. • Pneumothorax – sudden pleuritic chest pain, absent breath sounds. • PE – unexplained hypoxia, pleuritic pain, risk factors. • CHF (low EF) – the most dangerous one to miss before you push AV nodal blockers. • Workup tools: ABG, BNP, CTPA, CXR, POCUS.⸻🧠 Why This Matters • Sinus tachycardia is often appropriate—but it can mask life-threatening systemic illness. • Medicating away compensation without treating the cause can pull the plug on the patient’s only survival mechanism. • STOP first before flipping to tachyarrhythmia algorithms (SVT, AFib w/ RVR, VT, Torsades, VF).⸻⚡ Clinical Pearls • Always ask: Stable or unstable? Unstable → Shock immediately per ACLS. • If stable → STOP. Consider secondary compensations before rhythm drugs. • POCUS is your left-hand tool—look for low EF before you dare to push AV nodal blockers. • Gradual vs sudden onset helps distinguish sick-tachy (gradual, compensatory) from tachy-sick (primary arrhythmia, often sudden). • Repetition is your friend—STOP, STOP, STOP until it becomes second nature.⸻🎧 In this episode, you’ll learn how to build a jetpack framework for HR >150 that keeps you calm under pressure, helps you avoid rookie mistakes, and makes sure you never miss the underlying killer hiding beneath “just a fast heart rate.”STOP first. Then treat.

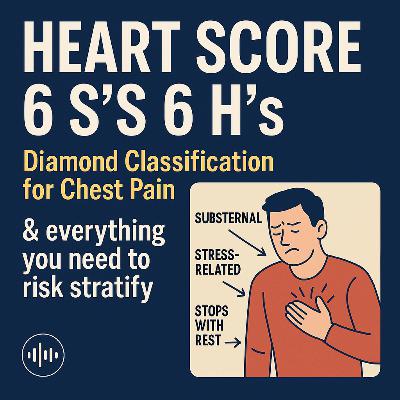

Chest pain is one of the most common—and highest risk—complaints in the ED. Missing acute coronary syndrome can be catastrophic, but keeping every patient in the hospital isn’t realistic either. That’s why the HEART score has become the standard of care: a simple, validated tool to help you decide who is safe for early discharge and who needs further workup or cardiology assessment.In this episode, I’ll show you how to remember and apply the HEART score effortlessly by flipping it into the 6 S’s and 6 H’s framework—a diamond-shaped way to risk-stratify chest pain that you can run through in real time, right at the bedside. This method blends the Diamond classification of angina with the HEART score, anchoring it to recall cues you’ll never forget. Once you master the S’s and H’s, you’ll be able to calculate HEART quickly, communicate clearly, and avoid missing high-risk patients.Of course, always follow your local protocols—but for every chest pain encounter, remember: ALWAYS calculate the HEART score.⸻💎 6 S’s & 6 H’s: The FrameworkS’s — Symptoms, ECG, Risk factors, AgeSuspicious Symptoms (Diamond criteria)1 . Substernal Stress-related (worse with exertion) Stops with rest Bonus: Sweating→ Typical angina = 3/3→ Atypical angina = 2/3→ Non-anginal = 0–1 ST Changes on ECG Normal → 0 Non-specific (LVH, digoxin, etc.) → +1 Significant ST depression/elevation → +2 Smoking (or Vaping) Still a major ASCVD risk factor Ask specifically in younger patients Sixty-Five (Age ≥65) <45 → 0 45–64 → +1 ≥65 → +2⸻H’s — The Highs & History High Cholesterol (Hyperlipidemia / LDL) High Sugar (Diabetes) High BP (Hypertension) Heavy (Obesity, BMI >30) History (Family hx <65, personal hx MI/CAD/PCI/CVA/PAD) High Troponin 1–3× normal → +1 >3× normal → +2⸻⚠️ Pearls & Pitfalls MACE = Major Adverse Cardiac Events. HEART pathway randomized trial (Mahler, 2015) → validated early discharge. The HEART score is not universal—there are exceptions; know when it doesn’t apply. Enough S’s & H’s → They Stay in the Hospital.⸻👉 Whether you’re on shift, teaching, or reviewing for boards, this episode makes the HEART score second nature. Save time, reduce misses, and risk stratify chest pain with confidence.

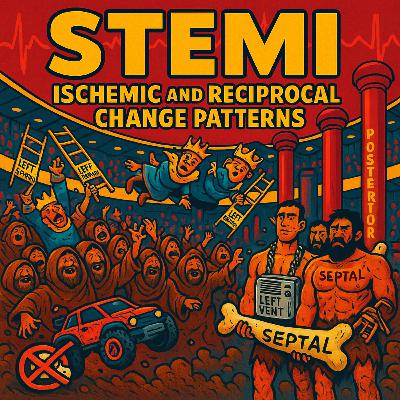

In a cardiac emergency, pattern recognition saves lives. The ability to rapidly identify ST-elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMIs) — and recognize their reciprocal changes — is one of the most high-yield clinical skills you can master. But memorizing lead groupings, artery territories, and reciprocal zones can feel abstract… until now.This podcast brings EKGs to life inside a colorful, stadium-themed world where each ECG lead is a character in the crowd — making it dramatically easier to remember the key patterns of ischemia and their reciprocals. Whether you’re a student, clinician, or educator, this episode transforms clinical EKG interpretation into vivid, unforgettable storytelling.🧠 Characters You’ll Meet: • Inferior Peasants (II, III, aVF) — Dirty, disheveled townsfolk crowd-surfing with broken RC cars (Right Coronary Artery), holding crossed-out nitro packs to remind us: No nitro in RCA infarcts! • Royal Ladder Holders (I, aVL, V5, V6) — Crowned kings and queens dropping through trapdoors as reciprocal ST depression hits the lateral leads, each holding golden ladders labeled Left Circumflex. • Cavemen with Septal Bones (V1–V2) — Giant-nosed, primitive figures gripping a huge bone marked SEPTAL, standing just in front of… • Shirtless Musclemen (V3–V4) — Tattooed with the word Anterior, these strongmen are chained to a floating AC unit labeled Left Ventricle — representing the LAD (Widowmaker). • Posterior Posts (V7–V9) — Hydraulic pylons rising behind the wall, symbolizing posterior MI that’s often missed without reciprocal signs.🎯 Quick Reference Patterns Covered in the Episode:⸻✅ Inferior MI (II, III, aVF)• ST elevation: Inferior leads• Reciprocal depression: I, aVL (high lateral)→ “When the peasants rise, the royals fall.”✅ High Lateral MI (I, aVL)• ST elevation: High lateral leads• Reciprocal depression: III, aVF→ Works both ways: “The balcony royals rise, the peasants fall.”✅ Posterior MI (V7–V9)• ST elevation: Posterior wall (not on standard 12-lead!)• Reciprocal depression: V1–V3→ “When posterior posts rise, septal cavemen drop.”✅ Anterior MI (V2–V4)• ST elevation: Anterior leads• Possible reciprocal depression: II, III, aVF→ Sometimes: “When the chest heroes rise, peasants tremble.”✅ Low Lateral MI (V5–V6)• ST elevation: Low lateral leads• Reciprocal depression: V1–V2 (septal)→ “Kings and queens rise, cavemen fall.”⸻🔥 Bonus Insights: • Why reciprocal changes matter: They can confirm a true STEMI, suggest a larger infarct area, and sometimes reveal hidden infarctions (like posterior MIs). • LBBB & Reciprocal Thinking: LBBB distorts ST segments, but understanding the mirror logic behind “William” (LBBB) and “Marrow” (RBBB) helps clarify expected patterns. ST depression in V1–V2? May just be part of LBBB — unless it’s concordant…📌 Use this episode as your visual and verbal anchor. Once you’ve seen the peasants, the royalty, the cavemen, and the Left Vent AC unit, you’ll never look at a 12-lead the same way again.

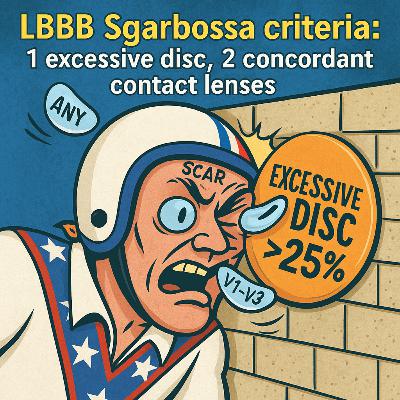

When a left bundle branch block (LBBB) throws a wrench into your ECG interpretation, how do you know if it’s a STEMI… or just baseline noise?In this unforgettable episode, we ride full throttle into the wild world of wide QRS complexes, Scarbossa criteria, and the modified rules that help unmask true occlusion amidst the electrical chaos.Visualize Evel Knievel launching off the QRS ramp — only to slam into the Left Bundle Branch Block cinder block. His forehead tattoo reads “Scar,” and as he collides, contact lenses fly from his eyes — one labeled “Any Lead ↑1mm” and the other, “V1–V3 ↓1mm” — representing concordant ST changes in opposite directions. Meanwhile, a giant frisbee labeled “EXCESSIVE DISC >25%” flies through the scene, reminding us of the Smith-modified criteria for proportional discordant ST elevation.You’ll learn: • Why LBBB and paced rhythms mask the usual signs of infarction • What “appropriate discordance” really means • The 3 ways Scarbossa criteria cut through the noise • How to visually anchor each criteria with unforgettable imagery • And why you only need one criteria to trigger concernThis episode breaks down advanced electrophysiology into a high-octane, cartoon-style teaching experience you’ll never forget. Whether you’re a medical student, resident, PA, NP, or attending, this episode locks in high-yield ECG wisdom that sticks.⸻✅ Smith-Modified Sgarbossa CriteriaUsed in Left Bundle Branch Block (LBBB) or Ventricular Paced Rhythm to detect Occlusion MI (OMI):You need only ONE of the following three to be positive: 1. Concordant ST Elevation ≥1 mm in any lead with a positive QRS➤ ST segment is in the same direction as the QRS (both upright) 2. Concordant ST Depression ≥1 mm in leads V1–V3➤ ST segment and QRS are both downward in V1–V3 (anterior leads) 3. Proportionally Excessive Discordant ST Elevation:➤ ST Elevation is ≥25% of the depth of the preceding S wave in a lead with a negative QRS➤ This replaces the old “5 mm” rule with a more accurate proportional one💡 You only need one of these three criteria to suspect occlusion MI in the setting of LBBB or ventricular pacing.Keywords: LBBB, Scarbossa Criteria, Modified Scarbossa, STEMI Equivalent, ECG Interpretation, Emergency Medicine, Paced Rhythm, Smith Criteria, Evel Knievel, Visual Mnemonics, Wide QRS, Electrocardiography, ST Elevation, ST Depression, STEMI Mimic, Cardiology, EM Boards

This is the most basic, essential framework for EKG interpretation — built for emergency medicine clinicians who need clarity, speed, and confidence in the heat of the moment.Our brains are wired for movement and story. Just like remembering your morning routine — wake up, brush teeth, grab caffeine — we naturally recall sequences that follow a simple, visual narrative. In this episode, we harness that power by turning EKG interpretation into Evel Knievel’s most daring stunt ride. It’s not just a fun story — it’s a high-yield, easy-to-remember mental checklist that sticks, even under pressure.🏥 Why it works in the ED:In emergency medicine, chaos is the norm. We don’t have time to think academically when a STEMI or arrhythmia is staring us in the face. That’s why we built this vivid, memorable sequence — rooted in the high-performance principle Michael Phelps used to win 23 Olympic gold medals: a set routine. You don’t rise to the occasion. You fall back on your training.🏁 What you’ll hear in this episode: 🏍️ Evel Knievel enters the EKG stadium: First, he scans for the big stuff — STEMI and reciprocal changes. 🛠️ Check engine light: T-wave inversions on his digital monitor. 📈 RPMs climbing: Smooth R-wave progression across the precordial leads. 🔍 Arrhythmia check: Is there a P for every QRS? 📏 The perfect ramp: PR interval = Evel’s takeoff — 120–200 ms. 🛵 Mobitz moped warning: PR lengthens before crashing (Wenckebach). ❌ Sudden moped disappearance: Mobitz II. ⚫ Unicycle of doom: Third-degree block — P and QRS totally disconnected. 🧠 Anomalies & Final Scan: Brugada, hyperkalemia (peaked Ts), Osborn waves, and when to order a posterior EKG.🚨 Key Takeaways to Remember: This story is your reliable sequence: scan for ischemia → check for arrhythmia → assess intervals. STEMI? Look for elevation + reciprocal depression — including the often-missed posterior wall (V7–V9). Rhythm? Ask: Is there a P for every QRS? PR = takeoff ramp. QT = safe landing zone. Mobitz I = gradual PR lengthening → dropped beat. Mobitz II = PR stays the same → sudden drop. Third-degree block = P and QRS divorced — high risk of instability. Brugada = beware of the “grave cross” in V1–V2. Ask about family history of sudden cardiac death. Prolonged QT = risk of torsades, syncope, or V-fib — know when to shock.🎧 This is your EKG blueprint. Your Michael Phelps routine. Your Evel Knievel ride to interpretation mastery.Let’s ride.

Step into the macrocytic anemia caboose and remember the non-megaloblastic causes with the mnemonic My Liver Bleeds a Lot: • My → Multiple Myeloma (CRAB: Hypercalcemia, Renal failure, Anemia, Bone lesions) • Liver → Liver disease • Bleeds → Hemolysis • A → Alcohol use • Lot → HypothyroidismWe start at the front half of the caboose with the non-megaloblastic nun holding a sign with crossed-out “mega” dynamite, marking the absence of hypersegmented neutrophils. The kingpin character raises an alcohol bottle (liver logo) in a toast—reminding us of alcohol as a cause—bumping it into his tuxedo labeled “TSH > 10” for hypothyroidism. Above him, three red balloons drip a drop of blood onto the liver logo, tying in the phrase “My liver bleeds a lot.”In the back half of the caboose, the B12 sumo baby wears a bandanna labeled “MMA” for methylmalonic acid (elevated in B12 deficiency), reaching up toward a Sistine Chapel ceiling to touch a finger labeled “↑ homocysteine” (seen in both folate and B12 deficiency). These back-half characters remind us that megaloblastic macrocytosis does have hypersegmented neutrophils, and is tied to DNA synthesis problems.For alcohol-related macrocytosis, we recall Wernicke’s encephalopathy—classic triad: 1. Ophthalmoplegia (eye movement abnormalities) 2. Ataxia (gait disturbance) 3. Confusion (altered mental status)ED Application: • In AMS + alcohol use, always give thiamine before glucose to prevent progression to Korsakoff syndrome (confabulation, severe memory deficits). • Macrocytosis without anemia can be an early alcohol toxicity sign—screen for liver disease, nutritional deficiencies, hypothyroidism, and myeloma. • Suspect multiple myeloma? Check calcium, renal function, Hgb, and order imaging for bone lesions. • Non-megaloblastic macrocytosis = treat underlying cause (alcohol cessation, thyroid replacement, liver management, transfusion for hemolysis). • Megaloblastic macrocytosis = give B12/folate; avoid masking B12 deficiency with folate alone to prevent neurologic damage.

In the fast-paced, high-stakes world of emergency medicine, every second matters—especially when it comes to sickle cell crisis. This podcast takes you straight to the heart of what matters most for ED clinicians, walking you through the essential “4 R’s” that can mean the difference between stabilization and rapid deterioration: • Recognize — Identify the telltale signs of sickle cell crises early. Understand presentations like acute pain episodes, acute chest syndrome, stroke, and splenic sequestration, and learn how to differentiate these from other causes of acute pain or respiratory distress. • Reverse — Act fast to correct life-threatening complications. From oxygen and aggressive IV fluids to urgent infection management, you’ll get evidence-based, bedside-ready strategies to halt progression. • Radiology — Know when and why to image. From chest X-rays in acute chest syndrome to brain imaging for suspected stroke, we’ll break down which modalities to order—and how to interpret findings in the sickle cell patient. • Refer — Recognize when escalation of care is critical. Whether to hematology, critical care, or transfer to a higher-level facility, we’ll cover the decision-making process and timing.Hosted with a focus on clinically relevant, ED-ready pearls, each episode blends: • Case-based storytelling — Putting you in the room with the patient, step-by-step. • Mnemonic-rich recall tools — Like our “crime scene outline” visual, with key stickers marking the 4 R’s across the patient’s limbs for fast memory anchoring. • Practical takeaways — What you can do immediately, what you must watch for, and what to avoid.The principles behind the Sickle Cell 4 R’s is delivered in a no-fluff, high-yield format designed for busy clinicians who want to sharpen their edge in real emergencies.Whether you’re a seasoned emergency medicine provider, a resident looking to solidify your sickle cell knowledge, or simply someone passionate about critical care, Sickle Cell Crisis: The 4 R’s will give you the skills and confidence to take decisive action when it matters most.

Hemolytic Anemias Mnemonic for the ED: TAG MY SUITCASEIn this high‑impact episode of Emergency Medicine Mind Palace, we break down hemolytic anemias into a memorable 5‑suitcase system that will stick with you on your next shift.If you’ve ever seen dark urine, anemia, or dropping hemoglobin and felt that twinge of uncertainty about which hemolytic process is at play, this episode will lock in the key visual cues and ED actions you need to recall under pressure.We explore the TAG MY SUITCASE mnemonic, where each suitcase represents a dangerous hemolytic anemia type:T → Thrombocytopenia suitcase (TTP / HUS / ITP / DIC / HELLP / HIT) • VW slug bug sticker with TTP & HUS clues • ITP “plate on the road” visual • DIC, HELLP, and HIT taped reminders • ED takeaway: These can kill fast—recognize the pentad, check for microangiopathic hemolysis, and know when to call heme & transfuse.A → Autoimmune hemolysis suitcase (Warm & Cold) • Warm side: Sun with spleen + IgG, holding butterfly (lupus) & RX bottle (drug‑induced) • Cold side: Blue hand with IgM, complement‑mediated, “cold agglutinin” with a tiny microphone (think Mycoplasma) • ED takeaway: Identify warm vs. cold; call heme; avoid cold exposure; supportive care first.G → G6PD suitcase (G6 Police Department) • Police badge, radical sticker with O₂ radicals attacking RBCs • Fava beans & Heinz ketchup with a bitten lid (Heinz bodies, bite cells) • ED takeaway: Stop the offending agent—the “police arrest the radicals.” Supportive transfusion only if unstable.M → Mechanical / ECMO suitcase (Sales Rep) • Heart valve + ECMO plush lung • Cola urine bottle (hemoglobinuria) & cardiology business card • ED takeaway: Shear stress causes hemolysis; check urine, hemolysis labs, MAP not pulse; coordinate with cardiology/CT surgery.S → Sickle Cell suitcase (Crime Scene Outline) • White briefcase with faint crescent RBC pattern • The 4 R’s for ED management: 1. Recognize – Sickle crisis & life‑threatening complications 2. Reverse – Pain control, oxygen, fluids, antibiotics (Uno reverse card sticker) 3. Radiology – Targeted imaging: CT head, CXR→CT chest, CTA limb, priapism eval 4. Refer – Heme, Neuro, Vascular, Urology early • X marks on chest, brain, leg, pelvis: Acute Chest, Stroke, Limb Ischemia, Priapism⸻By the end of this episode, you’ll be able to: • Rapidly recognize which hemolytic anemia you’re facing • Recall ED priorities and life‑saving interventions • Use the TAG MY SUITCASE mnemonic to never miss a high‑risk patientKey ED Reminder: • Stabilize first, follow local protocols, and call for help early. • When in doubt, think: Recognize → Reverse → Radiology → Refer.🎧 Listen now and step into the Hemolytic Anemia Mind Palace—where visuals and memory hooks turn complex hematology into rapid recall.

Step aboard the Anemia Train and enter the Normocytic Skeleton Car—the middle car of your anemia mind palace—designed specifically for busy ED clinicians who need fast recall without flipping through textbooks.In this episode, you’ll: • 🧠 Visualize the Normocytic Train Car: Skeleton passengers holding reticulocyte balloons, split by a divider wall between low retic (front) and high retic (back). • 🎈 Lock in Retic Logic for the ED: • Low retic = Hypoproliferative (CKD with low EPO / Aplastic with high EPO but no marrow response) • High retic = Hyperproliferative (Hemolysis vs. Acute Blood Loss) • 🩸 Master Key ED Presentations: • CKD skeleton with sagging balloon (↓EPO), struggling for signal on a dead cell phone • Aplastic skeleton with a ringing phone he can’t answer, sitting on a frying pan (pancytopenia) • Hemolytic skeleton with bursting balloons, a Reuben sandwich with a lemon (↑LDH), stepping on a smiley‑face sticker (↓haptoglobin) • Acute Blood Loss skeleton in a puddle of blood, holding a GBS ping‑pong paddle (Glasgow‑Blatchford), with a soft BP cuff falling off his arm reminding you to check code status and be MTP ready • 🧳 Tour the Hemolytic Suitcases (final segment): 1. TTP/HUS VW suitcase with 5 bullet holes and brown diarrhea door → plasmapheresis + fluids 2. Autoimmune suitcase: Warm IGG sun w/ spleen & butterfly, Cold IGM iceberg with blue hand → consult heme 3. G6PD suitcase: G6 Police Dept badge, fava beans, Heinz ketchup bite cap, “Radical” free radical sticker → stop offending agents 4. Medical Sales suitcase: Heart valve + ECMO plush lungs, cola urine bottle, business card for cardiology → check hemolysis panel & hemodynamics⸻Why It Matters in the ED • 🚨 Rapid Retic Check = Life‑Saving Triage: Quickly determine production vs. destruction vs. loss • ⚡ Know When to Act: • Hyperproliferative side = ED danger zone (hemolysis & acute blood loss) • Hypoproliferative side = usually outpatient follow‑up unless profoundly symptomatic or pancytopenic • 💉 Immediate Actions: • Transfuse if symptomatic or unstable • Initiate MTP for massive GI bleeds • Call heme or GI early for high‑risk or crashing patients • 📊 ED Labs to Prioritize: CBC w/ indices + retic, hemolysis panel, type & screen, stool/urine checks as indicated⸻Disclaimer:This podcast is for educational purposes only. Always check local ED protocols and consult specialists for patient‑specific management.

Microcytic Anemia in the ED: What You’re Missing Could Kill Your Patient🚨 Episode Summary for the Emergency Clinician:Think you’ve got anemia figured out? Think again. In this high-yield episode, we dissect microcytic anemia from an ED-first perspective and break down what you must recognize and act on fast—because missing a few key clues could mean a delayed diagnosis with deadly consequences.🛤️ Using a train engine metaphor, we bring the microcytic workup to life—making it unforgettable under pressure. This is the engine of our anemia workup, where iron studies and immediate red flags demand your attention.👁️🗨️ Key Clinical Takeaways: Microcytic = MCV < 80: Think iron first—but don’t stop there. The Big 3 Microcytic Causes:🧲 Iron Deficiency Anemia (↓ ferritin, ↑ TIBC)♨️ Anemia of Chronic Disease (normal/high ferritin, ↓ TIBC)🧬 Thalassemia (abnormal Hb electrophoresis) Sideroblastic Anemia & Lead Poisoning: Don’t forget these rare but real zebras—especially if you see basophilic stippling.💉 Emergency Treatment Highlights: Iron Deficiency: Consider transfusion if symptomatic with Hb < 7 (or < 8 if cardiac hx). Oral or IV iron outpatient. Anemia of Chronic Disease: Address underlying infection/inflammation. Transfuse only if symptomatic. Thalassemia: Usually no ED intervention unless severe. Do not give iron unless iron-deficient is confirmed. Lead Poisoning / Sideroblastic: Suspect in the right exposure history. Stabilize and refer.🧠 Why This Matters in the ED: Microcytic anemia is often dismissed—but a dangerously low hemoglobin could be your first and only clue to an occult GI bleed, chronic renal disease, or even a missed malignancy. Every CBC is a vital sign. Recognizing pattern + initiating the right early steps = saving a life. Don’t just discharge with “follow up”—ask why the anemia exists.💡 Memory Aids Included:We walk through vivid memory palace metaphors and layered symbolism (like sagging balloons, cloaked villains, and signal-less cell phones) to help you recall labs and differentials on shift—when it matters most.📋 Quick Lab Tips: Iron studies: Order ferritin + TIBC if microcytic. Hemoglobin Electrophoresis: If you suspect thalassemia. Peripheral Smear: For RBC morphology clues (target cells, basophilic stippling, etc.). CRP/ESR: Helpful when working up chronic inflammatory states.⚠️ What You’re Missing Could Kill Your Patient:This isn’t a textbook review—it’s ED pattern recognition and decision-making under pressure. Catch microcytic anemia early, treat aggressively when needed, and don’t miss the opportunity to spot slow bleeds or signal bigger systemic diseases.📎 Disclaimer: This episode is intended for medical education only. Always refer to your hospital’s local protocols and consult specialists as needed.

In this high-yield episode, we build a visual memory palace down the “Highway to Hell” of emergency thrombocytopenia syndromes. Each stop reveals a unique and dangerous cause of low platelets you’ll encounter in the ED—brought to life through vivid storytelling, unforgettable characters, and layered mnemonics.🚑 What You’ll Learn (Quick Hits): • TTP – Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura⚠️ Medical emergency! Think fever, renal failure, confusion, and schistocytes. LDH ↑, haptoglobin ↓. No platelets? No transfusions—start plasma exchange. • HUS – Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome👶 Usually in kids post-E. coli O157:H7 diarrhea. Watch for MAHA, AKI, and thrombocytopenia. Supportive care is key. • ITP – Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura🍽 Isolated platelets on the floor. In kids: post-viral; in adults: chronic. No MAHA. Often treated with steroids or IVIG. • DIC – Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation🎲 The DIC casino. Caused by trauma, sepsis, OB complications, or malignancy. PT/PTT ↑, D-dimer ↑, fibrinogen ↓, schistocytes present. Treat the cause! • HELLP – Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, Low Platelets🔥 Pregnant patient near the end of the road—hypertension, RUQ pain, and MAHA. Delivery is the only definitive treatment. • HIT – Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia🕷 A clotting catastrophe. 5–10 days post-heparin. Watch for new clots and falling platelets. Stop heparin and start a direct thrombin inhibitor like argatroban.💡 Distinctions to Remember: • MAHA: Present in TTP, HUS, DIC, HELLP (look for schistocytes, LDH ↑, haptoglobin ↓). • Isolated thrombocytopenia: Think ITP. • Timing: HIT = 5–10 days after heparin; HUS = 5–10 days after diarrheal illness. • Treatment: TTP = plasma exchange, DIC = treat cause + FFP/cryoprecipitate, HELLP = deliver, HIT = stop heparin.—🧠 Bonus: Visual mnemonics and character scenes help lock it all in. This episode blends storytelling, pathophys, and pattern recognition so you’ll never forget what each condition looks like in real life.📌 Save it. Share it. Pass your boards. Help your patients.

In this unforgettable bloody podcast, we bring the clotting cascade to life through a cast of hilarious and high-yield characters designed to make clinical recall effortless under pressure.Play Table Tennis = PTT = Inside = Intrinsic. Play Tennis = PT = Outside = Extrinsic.”You’ll meet:🟢 Lucky Number 7 — our tennis-playing war cry–shouting Factor VII who kicks off the extrinsic pathway by yelling “This is WAR!” 🎾 Warfarin is his signature drug, and he’s monitored using PT/INR. 🔵 Inside, we find our Intrinsic Table Tennis Team: • Factor XII – Haggard from Hogwarts: Looks impressive but doesn’t cause bleeding (aPTT prolonged, no clinical bleeding). • Factor XI – The Ashkenazi Post-Op Guy: Mild bleeding, especially post-surgery. • Factor IX – Hemophilia B Player: Jersey with a bold upside-down 9 (“B”) — classic for Hemophilia B (X-linked, prolonged aPTT, normal PT). • Factor VIII – “Dave the ATE Guy”: Sporting an “ATE” shirt and bitten fruit logo — he’s your clue for Hemophilia A (treated with Factor VIII or DDAVP).“Ate = Eight = Hemophilia A” and “B = looks like upside-down 9 = Hemophilia B.”🔴 In the Commons, you’ll meet: • Jason from Friday the 13th: Our grim reaper of clotting, holding the bills for Factors 10, 5, 2, 1, and 13. • Prothrombin (Factor II) — aka “Thumb Bill”: Turns into thrombin (the $2 bill with a big thumbprint) and activates fibrinogen (the $1 bill made of fiber) into fibrin. • Factor XIII (Jason again) then seals the clot with a sticky web. The clot is locked. Game over.🌿 Then enters Heparin: A barefoot hippie who amplifies Antithrombin the Ferret 🐾, whose collar reads “10 & 2 Stopper.” • Heparin inactivates Factor 10a and Thrombin (2a), preventing the clot entirely. • Heparin’s work is monitored by aPTT (not PT/INR).Mnemonic: “Check the aPTT!” echoes across the commons as the web dissolves.✅ Quick Clinical Takeaways: • Hemophilia A = Factor VIII deficiency → Treat with Factor VIII or DDAVP • Hemophilia B = Factor IX deficiency → Treat with Factor IX • Both: X-linked, prolonged aPTT, normal PT • Heparin = Acts on Factors 2a & 10a, monitored by aPTT • Warfarin = Inhibits Factor VII, monitored by PT/INR👨⚕️ Built for emergency physicians and learners who want fast recall, sticky mnemonics, and a clotting cascade you’ll never forget.

In this episode, we tackle STEMI mimics—conditions that mimic ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction on an EKG but aren’t always a heart attack. Why’s it critical? Because ST elevation doesn’t always mean STEMI, and misdiagnosis can waste time or miss critical conditions. ELEVATIONElectrolytes (Hyperkalemia), Left Bundle Branch Block, Early Repolarization, Ventricular Hypertrophy (Left), Aneurysm (Ventricular), Thailand (Brugada Syndrome), Inflammation (Pericarditis), Osborn J Wave, Non-Ischemic VasospasmWe use the ELEVATION mnemonic to guide you through each mimic with clear explanations, repeated key points, and rapid-fire quizzes to lock in your recall.

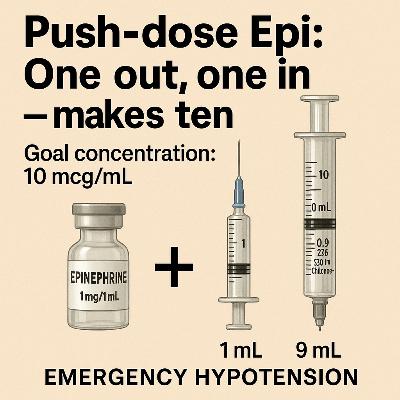

How to Mix Push-dose Epi: One out, one in — makes tenGoal concentration: 10 mcg/mLStep-by-Step Mixing: 1. Start with a 10 mL syringe of normal saline (NS) • empty 1 mL to retain 9 mL of NS in the syringe. 2. Use the code cart 1:10,000 epi (100 mcg/mL) • This is the standard “cardiac arrest epi” amp (usually 1 mg in 10 mL)…the 1:10,000 prefilled syringe used during ACLS 3. Withdraw 1 mL of the 1:10,000 epi (this gives you 100 mcg) using 3 mL syringe. 4. Inject that 1 mL (100 mcg) into your syringe of 9 mL NS. • Now you have 10 mL of epinephrine at 10 mcg/mL — ready to use.So what we just did is the mnemonic: One out, one in — makes ten⸻• What’s the concentration of the code cart epi? • How much do you withdraw? • What do you inject it into? • What’s the final concentration?You should be able to say it out loud, now. If not — just repeat the podcast a couple of times to get it solid.⸻How to Administer: • Dose: 1–2 mL IV push every 1–5 minutes PRN hypotension • That’s 5 to 20 micrograms per dose — meaning 0.5 to 2 mL of your push-dose epi, depending on the patient’s response. • Titrate to clinical effect (aim for MAP >65 or ROSC support)

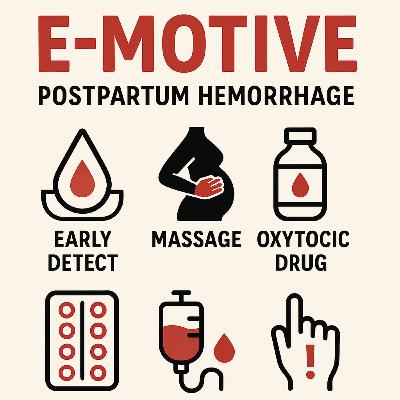

E-MOTIVE Mnemonic for Postpartum Hemorrhage: A Lifesaving StrategyThe E-MOTIVE mnemonic stands for a six-component bundle aimed at tackling postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), a major cause of maternal death, especially in low-resource settings. This approach, tested in a cluster-randomized trial across 80 hospitals in Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania, was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2023. Here’s what E-MOTIVE stands for and why it matters: • E – Early Detection: Uses a calibrated blood-collection drape to objectively measure blood loss after vaginal delivery. This ensures PPH (blood loss ≥500 ml) is identified quickly and accurately, unlike visual estimation, which can be unreliable. • M – Massage: Uterine massage is performed to stimulate contractions and control bleeding, particularly for uterine atony, the most common cause of PPH. • O – Oxytocic Drugs: Administers drugs like oxytocin to promote uterine contractions and reduce bleeding. These are critical for managing uterine atony effectively. • T – Tranexamic Acid: An antifibrinolytic drug given to stabilize clots and reduce bleeding, especially when administered early after PPH onset. • I – Intravenous Fluids: Provides fluids to maintain blood volume and prevent shock in women experiencing significant blood loss. • V – Vaginal Examination and Escalation: Involves a thorough genital tract exam to identify trauma or retained tissue, with escalation to surgical or advanced care if bleeding persists. • E – Effective Teamwork: Emphasizes communication, cooperation, and rapid response among healthcare providers to ensure all components are delivered promptly.Why It’s a Game-Changer: The trial showed that E-MOTIVE reduced the risk of severe PPH (blood loss ≥1000 ml), laparotomy for bleeding, or maternal death by 60% compared to usual care. PPH was detected in 93.1% of cases in the intervention group versus 51.1% in the control group, and the treatment bundle was used in 91.2% of cases versus 19.4%. This bundle ensures evidence-based interventions are applied consistently and concurrently, saving lives by addressing PPH faster and more effectively.E-MOTIVE is a practical, scalable solution, especially for low- and middle-income countries where PPH is deadliest. Its use of low-cost tools like the blood-collection drape makes it accessible, while the mnemonic simplifies training and implementation for healthcare teams under pressure.This summary is based on the New England Journal of Medicine article.

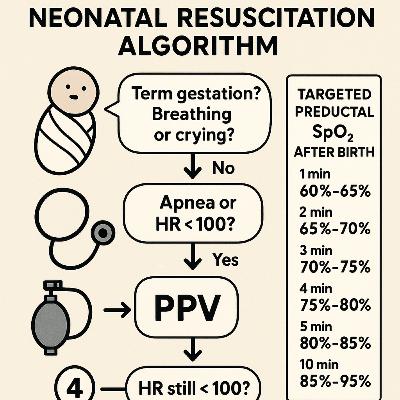

This is a Neonatal Resuscitation Algorithm flowchart, specifically the NRP (Neonatal Resuscitation Program), published by the AHA in 2020. It provides a step-by-step guide for healthcare providers to follow during the resuscitation of a newborn immediately after birth, focusing on stabilizing the infant’s breathing, heart rate, and oxygenation.Starting Point • Antenatal Counseling and Team Briefing: Before birth, the team prepares and checks equipment. • Birth: The process begins at the moment of birth.Initial Assessment (Within the First Minute) 1 Term Gestation? Good Tone? Breathing or Crying? ◦ If Yes: The infant stays with the mother for routine care (warming, maintaining normal temperature, positioning airway, clearing secretions if needed, drying, and ongoing evaluation). ◦ If No: Proceed to resuscitation steps. 2 Apnea or Gasping? HR Below 100/min? ◦ If Yes: ▪ Start PPV (Positive Pressure Ventilation) using a SpO₂ monitor and consider an ECG monitor. ▪ Check if the heart rate (HR) is still below 100/min after PPV. ◦ If No: ▪ Check for Labored Breathing or Persistent Cyanosis. 3 Labored Breathing or Persistent Cyanosis? ◦ If Yes: ▪ Position and clear the airway, monitor SpO₂, and provide supplementary O₂ as needed. Consider CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure). ▪ Follow up with post-resuscitation care and team debriefing. ◦ If No: Continue with routine care as described earlier.Further Resuscitation (If HR Remains Low) 4 HR Below 100/min After PPV? ◦ If Yes: ▪ Check chest movement and take corrective ventilation steps if needed (e.g., using an endotracheal tube (ETT) or laryngeal mask). ◦ If No: Monitor and continue care. 5 HR Below 60/min? ◦ If Yes: ▪ Intubate if not already done. ▪ Start chest compressions coordinated with PPV using 100% O₂. ▪ Use an ECG monitor and consider an umbilical venous catheter (UVC) for access. ◦ If No: Continue monitoring. 6 HR Still Below 60/min After Compressions? ◦ If Yes: ▪ Administer IV Epinephrine. ▪ If HR remains persistently below 60/min, consider hypovolemia (low blood volume) or pneumothorax (collapsed lung) as potential causes.Additional Information • Targeted Preductal SpO₂ After Birth: The chart lists target oxygen saturation (SpO₂) levels for a newborn at different time intervals post-birth: ◦ 1 min: 60%–65% ◦ 2 min: 65%–70% ◦ 3 min: 70%–75% ◦ 4 min: 75%–80% ◦ 5 min: 80%–85% ◦ 10 min: 85%–95%ContextThis algorithm is used in clinical settings, particularly in delivery rooms or neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), to guide healthcare providers in managing newborns who aren’t breathing adequately or have a low heart rate at birth. It emphasizes rapid assessment and intervention to ensure the infant stabilizes within the critical first minutes of life.

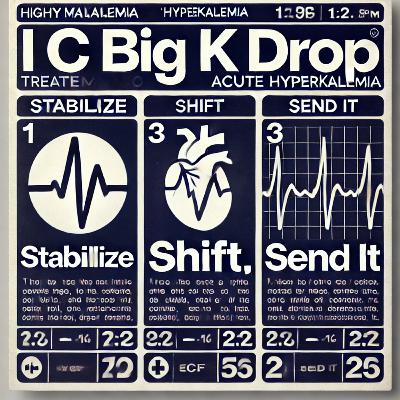

The 3-Step Approach to Acute Hyperkalemia 1. Stabilize: the Heart (If ECG changes) → Calcium 2. Shift: K+ Into Cells → Insulin + Glucose, Albuterol, Bicarb (if acidotic) 3. Send-it: Remove K+ From Body → Diuretics (if making urine), Kayexalate (if GI motility intact), Dialysis (if severe/refractory)I – IV FluidsC – CalciumB – Beta-2 AgonistsB – BicarbonateI – Insulin & GlucoseK – Kayexalate (Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate)D – DiureticsD – Dialysis1. First Step: Assess ECG & Risk of Arrhythmia • Peaked T waves, QRS widening, sine wave = Give Calcium ASAP • Calcium doesn’t lower K+, but it prevents cardiac arrest. 2. Temporary vs. Definitive Treatments • Shifting K+ into cells (Beta-agonists, Bicarb, Insulin) buys time. • Excreting K+ (Diuretics, Dialysis, Kayexalate) removes K+. 3. Timing of Interventions: • Calcium: Immediate (stabilizes heart). • Insulin/Albuterol/Bicarb: 15–30 min (shifts K+). • Diuretics/Kayexalate: 1–6 hours (removes K+). • Dialysis: Immediate, definitive. 4. Common Pitfalls & Pro Tips • Insulin can cause hypoglycemia – recheck glucose in 30 minutes. • Albuterol requires high doses – typical 2.5 mg nebs won’t cut it. • Bicarb only works if acidotic – don’t rely on it in normotensive patients. • Kayexalate is slow & controversial – consider patiromer or zirconium cyclosilicate instead in chronic cases. • If oliguric or ESRD → Straight to dialysis.

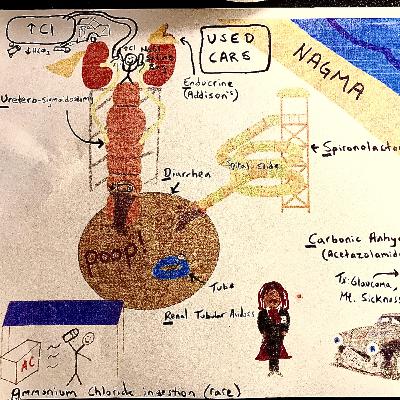

USED CARS mnemonic for non-anion gap metabolic acidosis (NAGMA):Why “USED CARS”? • Ureterosigmoidostomy • Saline & Chloride infusion (excessive).. chloride offsets AG • Endocrine disorders (Addison’s disease aka adrenal insufficiency, hypoaldosteronism) • Diarrhea • Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors • Ammonium chloride • Renal tubular acidosis • Spironolactone⸻U – Ureteroenteric fistula (or diversion surgery) • Why NAGMA? • Ureter attached directly to colon; bicarbonate lost into bowel, chloride absorbed, causing hyperchloremic acidosis. • Symptoms: • History of bladder/colon surgery, urine-like smell from stool, chronic acidosis. • Labs: Normal AG, elevated chloride, chronic metabolic acidosis. • ED Management: • Identify, refer to urology or general surgery for definitive repair. • Correct electrolyte disturbances (usually potassium, bicarbonate).⸻S – Saline Infusion (Excessive) • What: Excessive infusion of normal saline (0.9% NaCl). • Why (Pathophysiology): High chloride content of NS dilutes bicarbonate → hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis (common in hospitalized patients). • Symptoms: Usually subtle (fatigue, mild confusion, fluid overload signs). • Labs: Normal AG, hyperchloremia, normal renal function initially. • ED Management: • Switch to balanced solutions (Lactated Ringer’s, Plasmalyte). • Monitor fluid and electrolyte balance.⸻E – Endocrine Disorders (Addison’s Disease/Adrenal Insufficiency): • Why: Lack of aldosterone = inability to excrete acid & retain sodium. • Clinical Clues: Weakness, fatigue, low BP, dizziness, hyperpigmentation (skin darkening), abdominal pain. • Labs: Low sodium, high potassium, normal anion gap, metabolic acidosis. • ED Management: • IV fluids (Normal saline), hydrocortisone, monitor electrolytes closely. • Admit for adrenal crisis management.⸻D – Diarrhea • Pathophysiology: Loss of bicarbonate-rich fluids via stool → bicarbonate depletion. • Clinical Clues: Frequent watery stools, dehydration signs (tachycardia, low BP). • Labs: Normal anion gap, hypokalemia common, hyperchloremia. • ED Management: • Aggressive fluid resuscitation (often NS or LR). • Electrolyte replacement (especially potassium).⸻C – Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors (Acetazolamide) • Mechanism: Prevent bicarbonate reabsorption → bicarbonate loss → acidosis. • Clinical clues: Medication history (glaucoma treatment, altitude sickness prophylaxis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension). • Labs: Normal AG, mild hypokalemia, mild hyperchloremia. • ED Management: • Stop offending medication, supportive care, and electrolyte replacement.⸻A – Ammonium Chloride Ingestion • Mechanism: Direct chloride ingestion overwhelms bicarbonate buffers. • Rare cause today, often historical or industrial exposure. • Clinical clues: History of ingestion, occupational exposures, metabolic symptoms (nausea, vomiting, confusion). • Labs: Normal AG, hyperchloremia. • ED Management: • Supportive care, stop exposure. • Correct metabolic acidosis if severe (sodium bicarbonate IV if severe).⸻R – Renal Tubular Acidosis (RTA) • Mechanism: Kidneys fail to reabsorb bicarbonate or excrete acid properly. • Bicarbonate replacement. • Potassium correction (careful monitoring). • Referral to nephrology.⸻R – Renal Tubular Acidosis (Already covered above) • Included in detail in the “A” section, given its complexity.⸻S – Spironolactone (and other Aldosterone Antagonists) • Mechanism: Blocks aldosterone receptors → reduced acid and potassium excretion. • Clinical clues: Use in CHF, cirrhosis, hypertension treatment. • Hold spironolactone, manage hyperkalemia aggressively (calcium gluconate, insulin/dextrose, albuterol, kayexalate). • Consider bicarbonate if severely acidotic.

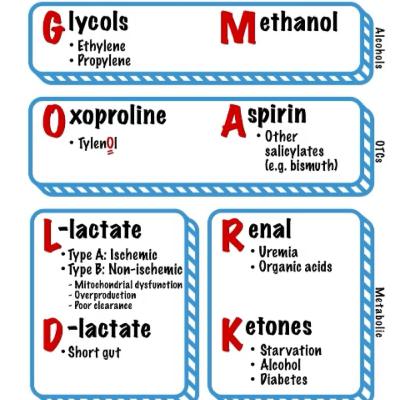

The GOLD MARK causes are divided into three major pathophysiologic groups based on the source of the acid production:1. Alcohols (Toxic Ingestions) → Emergency Toxins • Glycols → Ethylene glycol (antifreeze) and propylene glycol • Methanol → Windshield washer fluid, homemade alcohol substitutes • Why grouped together? • Common in suicide attempts, accidental ingestions, or chronic alcoholics. • Key labs: Serum osmolality, anion gap, osmolar gap. • Imaging: Calcium oxalate crystals on urine microscopy (ethylene glycol). • Treatment: Fomepizole or ethanol (blocks alcohol dehydrogenase), hemodialysis in severe cases.2. OTCs & Medication-Related Causes → Common but Easily Missed • Oxoproline → Chronic acetaminophen (Tylenol) use, often in malnourished patients • Aspirin → Salicylates, including bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) • Why grouped together? • Often overlooked in chronic users or the elderly. • Key signs: Tachypnea (respiratory alkalosis), tinnitus (aspirin), altered mental status. • Key labs: Salicylate level, ABG (mixed acid-base disorder). • Treatment: Alkalinization (sodium bicarb drip), dialysis for severe cases.3. Metabolic Causes → Endogenous Acid Production • L-lactate → Type A (ischemia), Type B (mitochondrial dysfunction) • D-lactate → Short gut syndrome, bacterial overgrowth • Renal Failure → Uremia, organic acids • Ketones → Starvation, alcohol, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) • Why grouped together? • These involve internal production of acids due to organ dysfunction. • Key labs: • Lactate level (for sepsis, ischemia). • BHB (beta-hydroxybutyrate) for DKA. • BUN/Cr for renal failure. • Urinalysis (ketones, glucose, uremia markers). • Treatment: • Fluids, treat underlying cause (DKA → insulin drip, renal failure → dialysis).Clinically Important Considerations for EM PhysiciansIn the ED, when a patient has metabolic acidosis with an elevated anion gap, think:1. What is the patient’s history? • Suicide attempt or confusion? → Alcohols, aspirin • Chronic Tylenol use or malnourished? → Oxoproline • Sepsis, shock, ischemia? → L-lactate • Short gut, diarrhea, recent antibiotics? → D-lactate • Known diabetes, alcoholism, or fasting? → Ketones • Chronic kidney disease? → Uremia2. What tests should I order immediately? • ABG/VBG → Confirms metabolic acidosis. • Anion gap calculation → Determines if the acidosis is anion gap or non-anion gap. • Serum osmolality & osmolar gap → Alcohol toxicity (ethylene glycol, methanol). • Lactate level → Sepsis, ischemia, mitochondrial dysfunction. • BHB (Beta-hydroxybutyrate) → DKA vs. alcoholic/starvation ketosis. • Salicylate level & acetaminophen level → Toxic ingestion screening. • CMP (BUN/Cr, glucose, liver enzymes, electrolytes) → Renal failure, DKA, liver dysfunction.Takeaway: What’s an Emergency? • Dialysis Emergencies → Methanol, ethylene glycol, severe aspirin toxicity, uremia. • Toxin Emergencies → Alcohols (treat with fomepizole), salicylates (alkalinization & dialysis). • Septic Shock / Tissue Hypoxia → Elevated L-lactate = immediate resuscitation with fluids & source control! • DKA → Fluids, insulin drip, and monitor for electrolyte shifts (esp. potassium).

Mister Ronald McDonald (MR RM) is a helpful flowchart for interpreting acid-base disorders, specifically for determining whether a patient’s condition is due to a metabolic (M) or respiratory (R) cause:1. Check the pH (7.4 is the cutoff) • pH > 7.4 → Alkalosis • pH < 7.4 → Acidosis2. Assess Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Levels (PaCO₂) • The key threshold is 40 mmHg: • If CO₂ > 40 mmHg, this suggests respiratory acidosis or metabolic alkalosis. • If CO₂ < 40 mmHg, this suggests respiratory alkalosis or metabolic acidosis.3. Determine the Cause • In Alkalosis: • If CO₂ > 40, the cause is Metabolic (M) Alkalosis. • If CO₂ < 40, the cause is Respiratory (R) Alkalosis. • In Acidosis: • If CO₂ > 40, the cause is Respiratory (R) Acidosis. • If CO₂ < 40, the cause is Metabolic (M) Acidosis.Key Takeaway • The chart helps determine whether a patient’s acid-base imbalance is due to a metabolic or respiratory cause by analyzing pH and CO₂ levels.