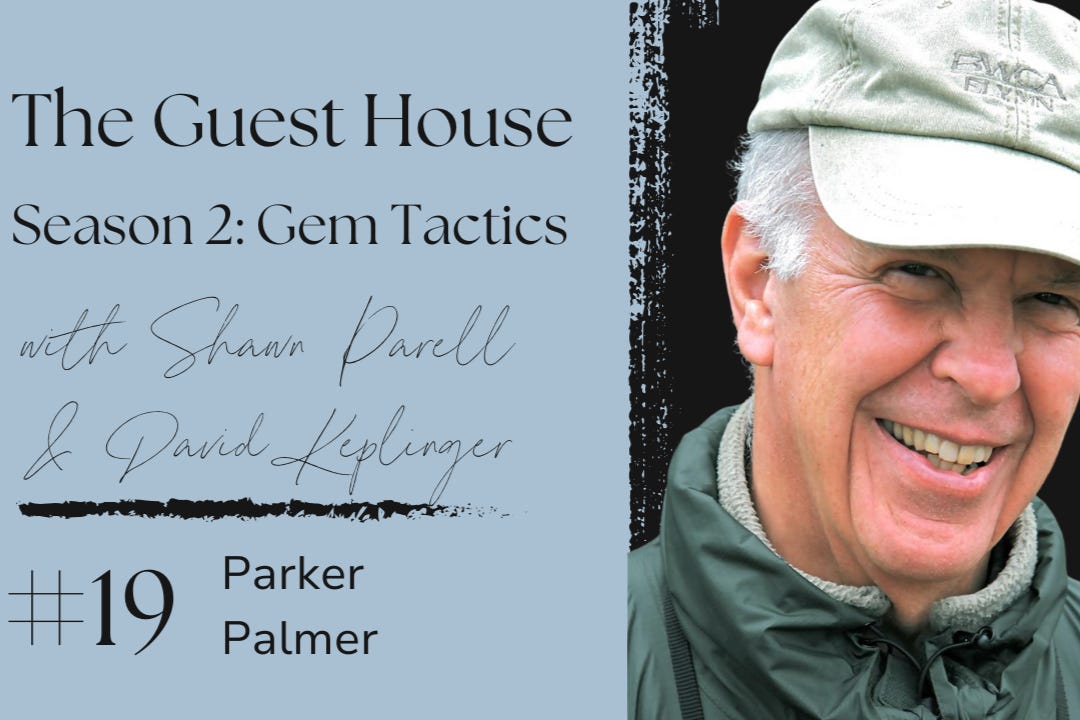

Discover The Guest House: "Gem Tactics"

The Guest House: "Gem Tactics"

The Guest House: "Gem Tactics"

Author: Shawn Parell and David Keplinger

Subscribed: 0Played: 34Subscribe

Share

© Shawn Parell

Description

Welcome to The Guest House, a commonweal meditation on the complexities and creative potential of being human in an era of radical change. In Season Two, cohosts Shawn Parell and David Keplinger are exploring what Emily Dickinson called "Gem Tactics," the practices by which we polish our creative engagement with life.

These conversations and contemplative writings are offered freely, but subscriptions make our work possible. Please bless us algorithmically by rating, reviewing, and sharing these episodes with friends—and consider becoming a paid subscriber if you’re able. Thank you!

shawnparell.substack.com

These conversations and contemplative writings are offered freely, but subscriptions make our work possible. Please bless us algorithmically by rating, reviewing, and sharing these episodes with friends—and consider becoming a paid subscriber if you’re able. Thank you!

shawnparell.substack.com

55 Episodes

Reverse

Just as there are darkened seasons in human history—times when the structures sustaining civilization collapse in on themselves and humanity finds itself stiff-fisted, grasping at brittle branches, slipping between worlds—so too is every individual subject to phases of undoing in the metamorphosis of a lifetime.Entering the chrysalis is rarely a matter of choice. We would resist if we could. One morning, we awaken with a pit in the stomach, a visceral unease that signals change even before we can name its source. Quite all of a sudden, we find we have entered a dream with no solid ground and no turning back. Loss feels imminent, along with the uncertainty of what comes next or how we will get there. We try to keep moving, mistaking busyness for control of circumstance. We hoist the blueprints of our former lives above our heads to keep them dry, trying to shore up what is already dissolving.We try very hard, as all creatures do, not to die. Yet for the caterpillar, entering the chrysalis is a form of programmed death—a gruesome act of self-digestion. What can the larva comprehend of its own metamorphosis as it surrenders to darkness and enzymatic dissolution? Before it can be reconstituted, the caterpillar’s whole body must pupate—which is to say liquify. Epithelial cells breaking down, muscles and mandibles lysed by their own enzymes, the entire body reduced to a nutrient slurry.Every winter, nature takes this serious turn. Fallen leaves coil in on themselves, roots retreat, seeds release, and stillness wraps the living world. Here’s orientation from a recent column in our cherished local magazine, the Santa Fe New Mexican —“In winter, our arid steppe climate shows us the value of leaving things alone. Grasses left standing become shelter. Seed heads become sustenance. Evergreen shrubs offer cover from wind and predators when the world feels most exposed. What looks untidy to us is, in fact, a carefully balanced system of protection and patience. The garden does not ask us to fix it in January—only to witness it.”The winter gardener knows not to try to fix such depression, but instead to witness and accompany the world beyond control. For the winter gardener recognizes the fallows as sanctuary, the outer casings of seed heads and pale grasses as fortresses of transformation, and death as a passage between birthing seasons. This is the winter gardener’s regenerative faith.Similarly, with respect to human development, Jungian analyst and author Marion Woodman called the chrysalis “a twilight between past, present, and future,” a place where the psyche must “tolerate annihilation—just long enough for the new form to begin assembling itself.” She described the sojourn of life as a series of “border crossings between what we were and what we cannot yet imagine.”For the caterpillar, the dream of the butterfly is carried by imaginal cells—tiny, sac-like clusters that, through the primordial twilight of metamorphosis, give rise at last to compound eyes, scaled wings—a new and elegant anatomy. This is how a creature built for crawling holds within its body the imagination of flight.In his 1910 Oxford lecture, The Birth of Humility, anthropologist Robert Ranulph Marett described metamorphic thresholds as “psycho-physical,” when body and mind falter so that “latent energies [may] gather strength for activity on a fresh plane.”The most courageous way we can enter the chrysalis is with attunement. “Pause,” Marett wrote, “is the necessary condition of the development of all those higher purposes which make up the rational being.” James Baldwin attested that the darkest hour can “force a reconciliation between oneself and all one’s pain and error.” We cannot will ourselves to grow, for transformation is an act of presence, not power. But within the privacy of our consciousness, with patience and attention, we can rediscover the forces shaping our evolution and develop faith in what is becoming.In Jungian terms, the collective mirrors the individual psyche: what deconstructs in the outer world—painfully, though necessarily—reflects what must be reimagined from within. Today, democratic principles and ecological balance are slipping from their axes. But, as Marett observed, “Not until the days of this period of chrysalis life have been painfully accomplished can [a person] emerge a new and glorified creature.”Some silent, imaginal knowledge within us already knows the way. Here in the high desert, the earliest bloomers will soon appear: proof that the intelligence of life has been preparing the ground, all along, for the resurrection of some new and common beauty.Together, we’re making sense of what it means to be human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House.+ Join next month’s yoga & meditation class on Thursday, Mar 12, at 9 am MT / 11 am ET. A replay will be shared via email shortly thereafter.+ Find me at YogaSource in Santa Fe every Wednesday morning, 9-10:15 am MT / 11 am-12:15 pm ET for Dynamic Practice. This class is fully analog—live and in person. Register through the studio here.+ I’ll be returning to two beloved places to offer retreats with friends in the coming year: Beyul Retreat, in the pristine wilderness surrounding Aspen, Colorado, May 21-25, 2026, with Wendelin Scott; AND world-class Ballymaloe House in County Cork, Ireland, Sept 20-26, 2026, with Erin Doerwald. Each retreat will feature yoga, meditation, farm-to-table meals, and curated outings—plus rest, nurturance, and imagination. Just a few spots left. Check out all the details here. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

Nearing the end of January, I’m only beginning to feel the sinew of this new year. Here in the United States, we’re reckoning with what seems like a sudden surge of authoritarianism—though, as Hemingway reminds us in The Sun Also Rises, collapse happens “two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.” The hubris we’ve unleashed from within now sends shockwaves through the world, unmooring the institutions we’ve depended on and unsettling the nervous system of our species.Staying human amidst the swirl has become a practice unto itself. We must maintain the pleasantries of our daily lives, yoke ourselves to the people and practices that organize and buoy the mind, and make actionable the indignance of our deeper values—all while sifting through the muck and shimmer of the collective unconscious.Of those in privileged circumstances, many are divesting themselves of accountability or arming up for an uncertain future. Even a question like “How’s it going?” can land strangely if it feels insulated from the existential tremors of the moment.Winter, of course, is the barest season. It’s a time when thin, long-shadowed light clarifies sight and stillness disciplines attention, when branches shiver as the wind exposes the decorative notions of warmer seasons.A few weeks ago, I sat down with two friends, David Keplinger and Lindsay Whalen, whose companionship is like wool wrapped around the cold turnings of life. Our purpose was to interview Lindsay about the poet Mary Oliver—the subject of her forthcoming biography from Penguin Press—and to trace the threads of synchronicity and coherence among us.I imagine that rendering anyone’s soul requires discipline and sustained concentration. But Mary’s life, as her poetry reflects, was singular, cloistered, and prolific, demanding of her biographer an uncommon devotion. In our conversation, Lindsay explained that she misses Mary less than she might another deceased friend, given that she remains in constant contact with her. Yet there’s one quality of Mary’s presence she said she misses: “When she looked at you, she really looked at you. It was a sustained gaze.” David, whose friendship with Mary spanned decades, smiled in agreement: “In her life, as in her work, she looked longer instead of looking away.”The word concentration derives from the Latin concentrātiō, meaning “the action or act of coming together at a single place.” It breaks down to con- (“together, with”) + centrum (“center”)—literally “bringing to a common center.” Originally, it described physical gathering, such as converging on a single point, and later evolved to refer to mental focus.In the prose collection Winter Hours, Mary distinguishes faith—“tensile, and cool, and [having] no need of words”—from hope, which she portrays more vigorously as “a fighter and a screamer.” And in her poem “The Clam,” we see how even a lowly, languageless creature is granted “a muscle that loves being alive.”Winter, too, does this work, sucking vital force inward to the quick. Every living thing must concentrate to survive. Trees shunt sap to heartwood and root; slow-breathing bears dream of thaw; squirrels make their caloric calculations. Even seeds, dark-bound beneath frozen ground, aspire toward germination.Hope, in this sense, is muscular. It is the fight to make the world a place we can live in. Not mere optimism, but the tender refusal to shut down in the face of suffering. It is the muscle that strengthens our will, linking imagination to endurance and promise to conviction.I have attempted several commentaries on this deranged geopolitical moment, wishing to say to friends around the world that we have a long history of abusive power dynamics to reckon with in the U.S.—which is no excuse. But we also have citizens like Renée Good, whose last words were “I’m not mad at you.”So, don’t give up on us.Even winter seems uncertain now, bringing tepid temperatures and pallid light where once it cut clean. So we train our gaze on what’s alive and here. We look closer, we grope for strength, for the sinews of our common sense—those cords that connect fibrous muscle to bare bone. A blackbird’s caw splits a sodden field. Hope does not flinch; it fastens.Together, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

Seven years after Mary Oliver’s death, her work feels even more vital, showing us how to love the world with its myriad faces.In this episode, we have the sincere honor of speaking with biographer Lindsay Whalen, whose forthcoming book from Penguin Press explores the life behind the beloved poet. Our conversation ranges from the poet’s focus on real life and her famous anonymity to David’s and Lindsay’s shared experiences with Mary in the years they knew her.Gathering these voices who represent the small group of surviving friends of the poet, the conversation goes deep into the links between Mary’s influence on Shawn’s practice as a yogi and therapist, David’s poetry, and Lindsay’s much-anticipated account of this singular human life.Lindsay Whalen is writing the first biography of the poet Mary Oliver, forthcoming from The Penguin Press. She is the recipient of the CUNY Graduate Center’s Leon Levy Center for Biography Fellowship and is a graduate of Brooklyn College’s MFA in Fiction. She began her career in publishing, and continues to work with authors as an independent editor.Resource Links:Learn more about Lindsay and her work:Upcoming Seminar: Lindsay Whalen on Mary Oliver and “The Human Seasons” *Begins Jan 20, 2026. Scholarship applications due by Friday, Jan 16, 2026.Instagram: @lwhalen13NYMag Article: How Mary Oliver’s Biographer Finally Met the Legendary PoetMore from David - book releases, workshops, mindfulness talks, upcoming events, and more:Website: Davidkeplingerpoetry.comInstagram: @DavidKeplingerPoetrySubstack: Another Shore with David KeplingerSubstack Author Page: https://substack.com/@davidkeplingerMore from Shawn - free audio meditations, upcoming events, retreats, monthly essays, yoga classes, and music alchemy:Website: Shawnparell.comInstagram: @ShawnParellSubstack: The Guest HouseSubstack Author Page: https://substack.com/@shawnparellTogether, we’re being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Bless our work algorithmically with your <3s and comments, and share this post with a loved one. Paid subscriptions make this offering possible. Thank you! This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

You’re invited next September 20-26, 2026, to The Tender Harvest, a week-long retreat amidst the golden hues and organic bounty of the world-class Ballymaloe House in County Cork, Ireland. Each day will feature yoga, meditation, farm-to-table meals, and curated excursions—plus ample time for rest, self-nurturance, and imagination.__I awake to the murmur of a boy speaking to his slumbering father. All night long, the darkening stillness of December had settled over the house, and, as usual, our son had scampered down the hall just before dawn, burrowed under a breathing mound of blankets, and reached toward whichever one of us was nearest. “I love you so much,” I hear my child sigh as he tucks himself beneath the warm weight of his father’s arm.I have no language to measure such a moment, ordinary though it may seem. I have only an attention born of it, a residue of tenderness reminding me that somehow –however improbable, fleeting, and marvelous – we are here together, and here at all.Later, diagonal rays of winter sunlight beam across the sky, a fact bright enough to leave an afterimage seared on the inside of my eyelids. Of this event, too, I keep only what impression remains: a momentary flash that lingers and softens.Which brings me to the medicine of tenderness—our capacity not just to intellectualize or conceptualize, but to feel the invisible textures of this living world. The word “tender” shares its etymological parent, the Latin word tendere–meaning “to extend outward or upward, to stretch toward or hold out, to offer; to direct toward, to aim toward”–with the verb “to tend,” in the sense of caring for, but also with “intention,” “attention,” and “tenders,” the small boats that carry people or goods from larger vessels to shore.A thruline here links the practices of intention and attention, guiding our consciousness toward what we care about, with a whole-bodied suppleness of presence. The metaphor of tender boats bridges the mutual nature of tenderness. How can one person’s practice of tenderness bring another to shore in a gradual and reciprocal softening of nervous systems? How is it that when one person rests with awareness in the tender weight of their body, heart, and mind, it can signal to another that their bruises are safe from further harm?Ezra Klein recently shared an interview with Patti Smith, the iconic musician, writer, and visual artist—sometimes called the “godmother of punk”—who rejects those labels wholesale. With a shrug that suggests the humbler, deeper values of her practice, she says, “call me a worker.” I love her for that.Many moments resonate in their conversation, but none so much as when she likens a good poem to a teardrop: “If you’re thirsty and you get that drop of water, it suddenly becomes the most welcome thing in the world.” My mind catches on what kind of thirst—what invisible needfulness—a good poem can satisfy. This is not the thirst of the yarrow or migrating whitethroat, not even the thirst of the bear in autumn. It seems a uniquely human thirst that calls out for the sincerity of real art.On the subject of death and spiritual thirst, Mary Oliver wrote: “Who knows what will finally happen or where I will be sent, yet already I have given a great many things away, expecting to be told to pack nothing, except the prayers which, with this thirst, I am slowly learning.”I believe this kind of thirst, of the nature of wanting to understand and be nourished by the mystery of our existence—by the grace of what it means that we are alive and able to wonder at the circumstances of our aliveness—dwells somewhere beneath the surface of every human being. This thirst lives in the unseen currents of heartache, uncertainty, and longing that flow like water beneath a frozen river.According to fellow poet Jane Hirshfield, Galway Kinnell once called “Tenderness” “the secret title of every good poem.” That line, for me, speaks to the particular mechanism within poetry that can meet such thirst. Tenderness is the dynamic tension between bearing witness to our shared fragility and strengthening our capacity for wholehearted presence and connection with ourselves and each other. It is the alchemy of kindness that can distill cold facts into feelings, thaw a hardened heart, and show us how we’re not alone. Like a teardrop, a gesture of tenderness can be small and exact, yet it can quench us with vital sustenance and healing.Strangely, the image of a teardrop has seeped into my morning practice like a quiet teaching. As I reach for some nearby poem, my mind skidding over the uneven terrain of the hours ahead, I pause to take a breath, and it occurs to me: I can carry a teardrop inside this day. Most authentic mindfulness practices seem strange to the outer gaze, but their effectiveness lies in the specificity and earnestness with which we orient toward them. So, here it is: a useful practice, an invisible resource to mind my life. One way I am learning to soften.__+ Join me every month for movement + meditation exclusively for paid supporters of The Guest House. Our next practice will be live on Thursday, December 18, at 9 am MT / 11 am ET, and will be shared via replay soon thereafter.+ Back to a regular studio class! Join me at YogaSource in Santa Fe every Wednesday morning, 9-10:15 am MT / 11 am-12:15 pm ET for Dynamic Practice. This class is live and not recorded. Join in-person or virtually from home. Register directly through the studio here.+ Two deeply envisioned retreats in the year to come: first at Beyul Retreat in the pristine wilderness surrounding Aspen, Colorado, for an extended Memorial Day weekend, May 21-25, 2026; then at world-class Ballymaloe House in County Cork, Ireland, September 20-26, 2026. All the details here.Together, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

In conversation with poet Parker Palmer, we trace the quiet art of listening for one’s true vocation, the solace of circles where no one is fixed or saved, and the long, harrowed path toward a wholeness that does not deny its own fractures.Parker J. Palmer is a writer, speaker and activist who focuses on issues in education, community, leadership, spirituality and social change. He is founder and Senior Partner Emeritus of the Center for Courage & Renewal, which supports people in every walk of life in nurturing deep integrity and relational trust for the sake of personal and social transformation.Palmer holds a Ph.D. in sociology from the University of California at Berkeley, fourteen honorary doctorates, and two Distinguished Achievement Awards from the National Educational Press Association. Among his honors, he is a recipient of the William Rainey Harper Award, previously given to Margaret Mead, Elie Wiesel, and Paolo Freire. In 2021, the Freedom of Spirit Fund, a UK-based foundation, gave him their Lifetime Achievement Award in honor of work that promotes and protects spiritual freedom.Palmer is the author of ten books—including several award-winning titles—that have sold over two and a half million copies and been translated into twenty languages. Anniversary editions of three of his books were issued in 2024: Healing the Heart of Democracy, A Hidden Wholeness, and Let Your Life Speak. An updated edition of On the Brink of Everything and a 30th anniversary edition of The Courage to Teach are due in late 2026.Resource Links:Learn more about Parker and his work:Website: Center for Courage & RenewalSubstack: Living the Questions with Parker J. PalmerSubstack Author Page: https://substack.com/@parkerjpalmer861952Facebook: Facebook Author PageMore from David - book releases, workshops, mindfulness talks, upcoming events, and more:Website: Davidkeplingerpoetry.comInstagram: @DavidKeplingerPoetrySubstack: Another Shore with David KeplingerSubstack Author Page: https://substack.com/@davidkeplingerMore from Shawn - free audio meditations, upcoming events, retreats, monthly essays, yoga classes, and music alchemy:Website: Shawnparell.comInstagram: @ShawnParellSubstack: The Guest HouseSubstack Author Page: https://substack.com/@shawnparellTogether, we’re being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Bless our work algorithmically with your <3s and comments, and share this post with a loved one. Paid subscriptions make this offering possible. Thank you! This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

You’re invited next September 20-26, 2026, to The Tender Harvest, a week-long retreat amidst the golden hues and organic bounty of the world-class Ballymaloe House in County Cork, Ireland. Each day will feature yoga, meditation, farm-to-table meals, and curated excursions—plus ample time for rest, self-nurturance, and imagination....Hordur is a descendent of Vikings. To arrive at his farm—4,000 windswept acres in Iceland’s storied BrennuNjáls Saga—is to step into an atmosphere rich with the scent of sulfur and soil, into a dramatic expanse of earth blanketed under heavy, silver-wrapped clouds.The light here is diffuse yet piercing, the landscape at once strange and wondrous—alive with an elemental force that reshapes the breath in our bodies as we ride through quick-watered rivers and cold, lush fields. I find my mind traversing the natural observations and human meanings of Annie Dillard’s Teaching a Stone to Talk: Expeditions and Encounters:“We are here to witness the creation and to abet it. We are here to notice each thing so each thing gets noticed. Together we notice not only each mountain shadow and each stone on the beach but, especially, we notice the beautiful faces and complex natures of each other. We are here to bring to consciousness the beauty and power that are around us and to praise the people who are here with us. We witness our generation and our times. We watch the weather. Otherwise, creation would be playing to an empty house.”Around a rustic dinner table of slow-cooked lamb and homegrown potatoes, Hordur shares some of his story with us. He recounts having lived abroad for decades, mastering the language of markets and margins in glass atriums of international finance—until, at fifty, an inexplicable, tectonic force called him home to the basalt and moss-softened fields that have cradled his lineage for a millennium.He explains simply: “I wanted to raise Icelandic children.”“But what does that mean to you?” we press.Hordur pauses briefly, then recalls the day his youngest, seven years old, began hitchhiking the thirty-minute ride from school. Through valleys quilted with lupine and sheep, she returned home each afternoon this way for a decade, delivered safely again and again by a series of outstretched hands.To absolutely trust one’s human surroundings is unfathomable to most parents. It points to an agreement not imposed by law, but woven into the fabric of society over generations, more gradually grown than moss over volcanic rock.It’s good to know communities on earth still exist where children are this safe. It’s good to know that somewhere, the fabled qualities of the village are alive and well.In a climate forged by fire and ice, tenderness is a currency of survival. Iceland has no standing military and virtually no violent crime. Babies nap outside in woolen blankets. Winter’s deep darkness—which consumes all but three hours of each day—is not dulled by drinking at bars but thawed and warmed in local geothermal pools. And, in the northern town of Akureyri, stoplights shaped like glowing red hearts—signaling people to stop in the name of love—began appearing during the 2008 economic collapse as emblems of support and resilience.One might be tempted to dismiss these signs of communal health as the baked-in benefits of a homogeneous culture, but the science and art of the commonweal warrant a deeper look.With what conditions can safety pattern itself into a nervous system? How can our collective nervous system down-regulate from its ratcheting mistrust? These are the questions of our times if we are ever to find our way back to ourselves and each other. They have no right to go away when our mutual keeping hangs in the balance.In the poem Small Kindnesses, Danusha Laméris writes:“What if they are the true dwelling of the holy, these fleeting temples we make together when we say, ‘Here, have my seat,’ ‘Go ahead—you first,’ ‘I like your hat.’”Years of teaching retreats in far-flung destination have sensitized me to Laméris’s notion of the “fleeting temples” we create. Strangers arrive without their creature comforts or daily certainties, often hesitant, eyeing each other warily, clutching their schedules and habits. Yet, by stepping into the strangeness of a new landscape and the invisible contours of each other’s lives, an organic, humanizing process begins to take shape. Stories and tinctures are exchanged; borrowed layers keep folks warm; adapters connect devices and new friends. Laughter begins to roll across the table. And then, on a long bus ride at day’s end, a head finds another’s shoulder to rest on: nascent, ephemeral, yes—but a temple nonetheless.“We have so little of each other, now. So far from tribe and fire. Only these brief moments of exchange,” Laméris’ poem admits. Trust is woven where human beings sew threads of kindness, respect, generosity, and mutual accountability. Intrinsic to our nature is this capacity to lean in, but our dignified work is to thread and re-thread our humanity, even in a darkening season.Stripped of the luxury of self-isolation, we confront what Annie Dillard refers to as “our complex and inexplicable caring for each other, and for our life together here.” This is our human weave, complex and inexplicable: the mycelium of our mutual existence.The famous children’s book asks, “Do you like my hat?” “I like your hat.” A benign, basic affirmation—just enough to signal safety to a nervous system. But out of these small kindnesses—a compliment, a door held open, a gentle word—the labor of civilization can begin anew.The day we return from Iceland, a vignette in juxtaposition: a grandmotherly figure spits an insult out the window of her car in our direction. My children freeze in the backseat, stunned by the woman’s venomous words and their unsparing ordinariness.Laméris’ poem laments this modern ache:“Mostly, we don’t want to harm each other… We want to be handed our cup of coffee hot, and to say thank you to the person handing it. To smile at them and for them to smile back.”When kindness is withheld, when someone’s pain is weaponized, some small but vital part in the mycelium tears. We feel the acute loneliness of being “far from tribe and fire,” and understand how the agitation that surrounds us gives tenderness more weight.Years have passed since Hordur returned to Iceland. He spends his days farming garlic, carrots, and potatoes in coarse soil, raising lamb on mountain herbs. His horses belong to one of the world’s oldest breeds—descendants of ninth-century stock. They graze in grassy fields through every season, their manes wind-whipped and their temperaments famously resilient.When asked how their nervous systems have evolved to be so even-keeled through the centuries, Hordur points out that Icelandic horses have no natural predators. They are exposed to the elements, he explains, and they prefer to weather Iceland’s brutal winters not alone in barn stalls, not in “an empty house” of creation, but with their fellow horses in an open field.Together, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

In this conversation with Meditation teacher Nolitha Tsengiwe, we explore how silence, presence, and practice can help us meet the joy and impermanence of life.Nolitha Tsengiwe is a Dharma teacher and board member at Dharmagiri Retreat Center in South Africa, which was founded by Kittisaro and Thanissara Weinberg. She has practiced since 1997 under Kittisaro and Thanissara, who are of Ajahn Chah’s lineage. In her first retreat with these beloved teachers, she discovered silence as a refuge and has never looked back. Nolitha completed the Community Dharma Leadership Program (CDL4) at Spirit Rock in 2014 and is a graduate of the IMS teacher training program from 2017 to 2021. Nolitha is a Psychologist and is trained in Karuna (Core process psychotherapy based on Buddhist principles) and Somatic Experiencing (SE). Has been a leadership development consultant and executive coach for over 20 years. She is a mother and teaches Biodanza (dance originated by Rolando Toro)Resource Links:Learn more about Nolitha and her work:Website: couragetolead.co.zaMore from David - book releases, workshops, mindfulness talks, upcoming events, and more:Website: Davidkeplingerpoetry.comInstagram: @DavidKeplingerPoetrySubstack: Another Shore with David KeplingerSubstack Author Page: https://substack.com/@davidkeplingerMore from Shawn - free audio meditations, upcoming events, retreats, monthly essays, yoga classes, and music alchemy:Website: Shawnparell.comInstagram: @ShawnParellSubstack: The Guest HouseSubstack Author Page: https://substack.com/@shawnparellTogether, we’re being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Bless our work algorithmically with your <3s and comments, and share this post with a loved one. Paid subscriptions make this offering possible. Thank you! This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

Adulthood has long been overlooked as a phase in human development. This is, in part, due to its implicit assumption of steadiness. Its shifting hues tend to be less dramatic than those of adolescence and elderhood, its moods less pronounced. Much of the time, we do the work of our lives, showing up for our common refrain while quietly learning to cultivate fulfillment on our own terms; our creative pursuits and revelatory practices often relegated to the margins of our daily lives.We are exceptionally connected, balancing our digital and analog lives. We are so busy. There is so much to do. Who has time? Adults say these things in exasperation, grasping for affirmation or companionship in the midst of their grievances. But it’s true—to be in the human world today is to drink from a firehose of information. Plus, what depths are safe to plumb outside the sanctuary of a therapist’s office or a park bench with a trusted friend? The stakes of vulnerability are high. So high, in fact, that Brené Brown describes judgment as “the currency of the midlife realm.” By midlife, we are expected to have brought to fruition the aspirations of our earlier selves—to have reached a plateau of practicality and resolve. Cruising altitude, as they say.Of course, we who inhabit or have inhabited the realm of adulthood know better. Inside the cornucopia of being human, spiraling inward from its bright surface, exist multitudes. Much like the tonal expressions of early autumn, the richer pigments of our psyche—previously concealed behind summer’s green façade—gradually reveal their layers to those who pay attention: ripening, sweetening, scenting the air with integration and maturation.~Today, I am writing from the belly of a meditation retreat at Vallecitos, among the ancient, indiscreet ponderosas of Northern New Mexico. Belly is a phrase I favor mid-retreat because it refers to the tender middle, the bellows, the digestive center. For five days, however brief an expanse of unclaimed hours, I have sat with myself in a wooden casita outfitted with a kerosene heater, a writing desk, and a chipmunk who makes neighborly visits to the stoop.There is a shimmer to this mountain valley nestled deep in the Carson National Forest—a million-acre, many-voiced wilderness. Everything breathes here. Cold morning dew washes the meadows; afternoon shadows sweep the valley. Here, the pines thicken into themselves, aspens become jittery and luminous as they dry in the breeze, and just beneath my feet, lichen and mycelium weave their storied logic.Ramón y Cajal, a Spanish neuroscientist who pioneered studies of the central nervous system at the turn of the 20th century, referred to neurons as “butterflies of the soul”—tender, erratic, natural, and necessary.Most days, I am like most adults. I move through a slurry of data and directives, my nervous system siphoning thoughts, words, plans, and presences. Most days, my neurons do not feel like butterflies. But the land’s knack is to shed and replenish, to dwell and allow and transform. A stone stays in place while the river glides over its surface, gradually polishing its form. I recall a beloved teacher once describing enlightenment simply as no more raw edges.There is a choreography to these days of sitting, walking, sweeping, sleeping; the routine is a slow, scaffolded unraveling. Contingent parts within me make themselves more visible to the naked eye: the part seeking a reprieve from boredom—hello, gorgeous organic berries at breakfast!—and the part that feels alive with fright on an unlit walk at night. The part that is slavish to comfort and sensitive to nonverbal exchanges in the lunch queue. The chronic clock-watcher who would count the hours until I see my family again…But also, there is a solitude I am befriending in my adult years—a creative and patient companion self. My nervous system grows almost amphibious here: reflective, tremulous, equilibrating like the surface of the alpine ponds of this valley. I imagine myself like the ancient city of Venice, which, during its pandemic-mandated reprieve from the normal throngs of tourists, welcomed dolphins back to its capillaried canals.I move through the forest, only to discover the strange phenomenon of the forest moving through me. The trees pass sideways; sunlight pitches down in mosaics, glancing off the backs of leaves. I rest on the round body of a pine, and the sound of critters, once a polite backdrop, sidles forward: bluebird, fox, nondescript scuttle from the bushes. The entire canopy hums—at me, through me—a polyphony the writer Amy Leach might call everybodyism, an ensemble of selfhoods.It is, if anything, a kind of organization I find myself settling into: organism, order—these words sharing root and logic. The fractal arrangements of life in the forest transmit glimpses of my body’s own sophisticated animal intelligence. Each muscle adjusts moment by moment to the terrain, dynamic and improvisational. The mind may imagine it stands apart—thank you, Descartes, for teaching us to narrate ourselves from above—but the world refuses such neat separations. Artificial intelligence, with its disembodied schemes, cannot meet moss or kneel to converse with mushrooms as we can.In her evening talk, Erin Treat, guiding teacher at Vallecitos, serendipitously shares the opening line from The Famished Road, a 1991 novel by Nigerian author Ben Okri that won the Booker Prize: “In the beginning, there was a river. The river became a road, and the road branched out to the whole world. And because the road was once a river, it was always hungry.” I think of this teaching as I move between stone and stream, insights replenishing from nowhere I can name. Dusk gathers, cliff shadows lengthen, and a presence stirs the forest, calling wandering creatures home.Together, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

In this episode, we talk with poet Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer about the grief that carries love through unimaginable loss—the death of a child—and of the daily practice of writing and mindful observation that dig the groundwork for self-forgiveness, compassion, and revelation.Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer is a poet, teacher, speaker and writing facilitator who co-hosts Emerging Form, a podcast on creative process. Her daily audio series, The Poetic Path, is on the Ritual app. Her poems have appeared on A Prairie Home Companion, PBS News Hour, O Magazine, American Life in Poetry, and Carnegie Hall stage. Her recent collections are All the Honey and The Unfolding. In 2024, she became poet laureate for Evermore, helping others explore grief and love through poetry. Since 2006, she’s written a poem a day, sharing them on her blog, A Hundred Falling Veils. One-word mantra: Adjust.Resource Links:* Explore these paths into Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer’s work for poems that fall daily, books that gather what cannot be held, albums that sing through the dark, and talks that change the way we see.Website: wordwoman.comDaily poetry blog: A Hundred Falling VeilsDaily poetry app for your phone: The Poetic PathPodcast on creative process: Emerging FormNewest Books: The Unfolding, All the HoneyTEDx: The Art of Changing MetaphorsPoetry album on “Endarkenment”: Dark PraisePoetry album on love in difficult times: Risking Love* More from David - book releases, workshops, mindfulness talks, upcoming events, and more.Website: Davidkeplingerpoetry.comInstagram: @DavidKeplingerPoetrySubstack: Another Shore with David Keplinger* More from Shawn - free audio meditations, upcoming events, retreats, monthly essays, yoga classes, and music alchemy.Website: Shawnparell.comInstagram: Shawn ParellSubstack: The Guest HouseTogether, we’re being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Bless our work algorithmically with your <3s and comments, and share this post with a loved one. Paid subscriptions make this offering possible. Thank you! This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

Welcome to The Guest House, a commonweal meditation on the complexities and creative potential of being human in an era of radical change. In Season Two, cohosts Shawn Parell and David Keplinger are exploring what Emily Dickinson called "Gem Tactics," the practices by which we polish our creative engagement with life.These conversations and contemplative writings are offered freely, but subscriptions make our work possible. Bless us algorithmically by rating, reviewing, and sharing these episodes with friends—and please become a paid subscriber if you’re able. Thank you!Poet David Keplinger joins The Guest House, and together we hold the doorway open to Gem Tactics—this season’s title—a term borrowed from a lesser-known Dickinson poem that refers to those small, faceted moves of inner cultivation that reveal the shape of a life.In the first episode of our second season, we trace the filament between practice and mystery. Our talk initiates an exploration of how we live, why we listen, and what it means to accompany and be accompanied in a time when so much is unraveling. This is the scaffolding of what’s to come: a season shaped less by expertise than by earnest inquiry, less by answers than by wholehearted questions.Resource Links* Check out David’s meditation and essay on our season title - Gem Tactics: Why We Practice.* More from David - book releases, workshops, mindfulness talks, upcoming events, and more.Website: Davidkeplingerpoetry.comInstagram: @DavidKeplingerPoetrySubstack: Another Shore with David Keplinger* More from Shawn - free audio meditations, upcoming events, retreats, monthly essays, yoga classes, and music alchemy.Website: Shawnparell.comInstagram: @ShawnParellSubstack: The Guest HouseTogether, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Bless our work algorithmically with your hearts and comments, and by sharing this post with a loved one. Paid subscriptions make this work possible. Thank you! This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

Love tenderizes everything. I tell myself this upon waking, when darkness gives way to dew and even the desert becomes supple again. Love tenderizes everything. I repeat it at dusk, as we sit on the portal and the sky swirls above us. I tell myself this when my daughter rests her head on my chest with a sigh, and murmur it like an incantation in moments when my heart feels cracked and crusted over, when the world’s roughness scrapes against my senses.Love tenderizes everything.Take, for example, Andrea Gibson’s “Say Yes.” I have carried this poem like an olive branch since my early twenties. It begins with the physics of resonance: “When two violins are placed in a room, if a chord on one violin is struck, the other will sound the note. If this is your definition of hope, this is for you.”I remember the heaviness I carried back then—the sense of distance I felt from myself and every other living thing, except for those few magnificent friends and family members who stayed near through that long, shadowed season. Yet somehow, the poet’s voice—two violins, a shared note—evoked the earthly harmonies of life, even then. Those lines nested inside me, tending to the wounded place as only poetry can: with its small sticks, feathers, and flickers of song.Grief is never singular. Like love, it layers in harmonics above the baseline of our existence. A father’s voice saying hi, sweetie, carries the ache of a future absence braided into today’s loving presence. There is grief for the unraveling of our ecological sanity and safety; for the unnamed burdens children carry, and our longing to keep them well and near. Sometimes there are wisps of sorrow for the unwritten books and furniture of that other life—the one I did not choose. There is grief, too, for the relentless rush of time, for how we quicken away from our bodies’ native pace.And then there are the most visceral reminders of our fragile, mutual keeping—the incontrovertible losses that stun with their seeming impartiality, confronting us with the vulnerability of a life that was just here but is no longer.Today, again, the world rushes in—unpredictable and uncertain. Thankfully, for this moment, I can adjust to a gentler lens. My body settles into the bruise, albeit tender to the touch. I want to tell everyone how needful it is to be kind, how we depend on love, and then I want to share the delight of a child who has just discovered raspberries fruiting on their vines.The weight of love—its 10,000 joys and 10,000 sorrows—shapes the day into something bearable and even, at times, beautiful. And in the wake of Andrea’s passing, as their words—earnest, luminous—seem all at once everywhere, startled into the air like a murder of crows in an open field, I find myself bowing to the gift of yet another poem that undoes me and then puts me back together again.“every time i ever said i want to die”by Andrea GibsonA difficult life is not lessworth living than a gentle one.Joy is simply easier to carrythan sorrow. And your heartcould lift a city from how longyou’ve spent holding what’s beennearly impossible to hold.This world needs thosewho know how to do that.Those who could find a tunnelthat has no light at the end of it,and hold it up like a telescopeto know the darknessalso contains truths that couldbring the light to its knees.Grief astronomer, adjust the lens,look close, tell us what you see.Together, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Please consider sharing this post with a loved one. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

The sound of flowing water soothes most nervous systems, but particularly those acclimatized to the desert, and particularly upon waking. I have struggled with sleep disturbances for most of my adult life, so it’s rare for me to experience the weight and metabolic satisfaction of a good night’s rest. But twice last month, I found myself receiving what we can call river medicine: first while visiting friends at their cabin in the Pecos Wilderness, and again east of Aspen, Colorado, while teaching at Beyul Retreat, a guest ranch along the Frying Pan River, a tributary of the Roaring Fork River.River medicine is like this: surrounded by tall, sappy pines, I found myself one early morning in the atmospheric valley between sleeping and waking, an integrative field of frequencies and forms. You know the place. Even now, I do not know for certain: did the river, by some charm of consciousness, stream into my dreamscape and stir me awake? Or was it the dream that pulsated forward into the matrix of a new day? What I can say is that I felt a bright, hydrous intelligence moving in ripples and waves through my body—clarifying and tonifying, calming neurons and glial cells in their watery beds, clearing layers of baked-in tension like grit loosened from a soaking pan. And for a time, I floated above the push of the day, appearing and disappearing and reappearing to myself.In the wake of hours that followed, to my delight, I noticed a quiet reverberation—an elemental answer quelling a wordless, needful thirst.Science offers a partial explanation for this. Water has a high dielectric constant, meaning it reduces the electrostatic attraction between charged particles, which helps substances like salt crystals separate and dissolve more easily. I would also propose that water’s properties of solubility, absorption, and transmission apply to its natural ability to clean and balance the bioenergetic forces of being human.When a river twists and turns, it releases negative ions into the air. Microscopically, this process is dynamic—even violent. Molecules spill over rocks and tumble forward, rushing and colliding, breaking apart, and thereby transferring electrons and charging the surrounding air. But I find comfort in this science of fluid revitalization. New, more supportive structures can form when old ones give way, pointing to how, beyond turmoil and devastation, we too can hope for vital transformation.Years ago, I read a New York Times article called “Where Heaven and Earth Come Closer,” in which journalist Eric Weiner wrote about “thin places,” locations where the gap between the ordinary and extraordinary—or, better yet, transordinary—thins out.“Thin” seemed to me a strange choice to describe where the air thickens with meaning. But Celts and early Christians held that a small but distinct distance, like three feet, separates heaven and earth—and that distance dissolves in “places that beguile and inspire, sedate and stir, places where, for a few blissful moments [we] loosen [our] death grip on life, and can breathe again.”Many a thin place has been built by human hands. Early in my career, I worked for the United Nations Foundation in collaboration with UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre, and developed the sensible habit of visiting the most treasured cathedrals, temples, and sanctuary sites wherever I found myself in the world. Jama Masjid in Delhi, Sacré-Cœur in Paris, Tirta Empul in Bali, Newgrange in Ireland, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem: each has a distinct energetic signature that lives in my memory, a resonance born of its purpose and the accumulation of countless prayers that infuse the surrounding air.But thin places are more often found than made. Mountains, canyons, coral palaces—they are organic monuments to mysticism and ready reminders of our humble size before nature. As Weiner writes, “Thin places relax us, yes, but they also transform us—or, more accurately, unmask us. In thin places, we become our more essential selves.”In this sense, thin places evoke qualities of alchemy and revelation. In traveling to Beyul Retreat, I recalled how the Vajrayana Buddhist term “beyul” refers to hidden valleys believed to be sanctuaries blessed by enlightened teachers, places where the land itself is animate. A beyul holds the wisdom that rivers, trees, and even rocks are not objects but mandalas — living altars, ineffable and intricate in their aliveness.Aptly named, Beyul Retreat is a place where the boundary between perception and imagination feels more permeable. The land electrifies with new growth as summer approaches: dandelion confetti bursts open in the meadows, aspen trees shimmy, and fresh sage scents the air. Each morning, as the river’s murmur moves through the valley, calypso orchids bloom in the shade while the pointed ears of silver fox pups perk up from behind cool, wet stones.In the imaginal realm of childhood, there are many such beyuls, many thin places. There are fern groves and swallow lairs, stars nestled in apple cores and galaxies in lightning bugs, and lobe-handed sycamore leaves at the wild end of the yard.We tend to think of nature as speaking in symbols, but its directness transmits rather than approximates. “The world is not made of objects; it is a communion of subjects,” writes Stephen Harrod Buhner, author of Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm. “To enter the imaginal realm is to give permission to the ineffable within us, to allow the world to speak through our senses, our dreams, our longings.”To commune is to listen with our whole body, to notice the most basic and vital exchange of breath and circumstance that underpins our existence. To allow for a metamorphosis of our attention. And when we realize the subjectivity of the world, we can discover strange and wonderful ways of joining the conversation. Like us, the aspens drink water and eat light. They have instincts and work to protect their lives. And did you know that the dark spots resembling eyes on the smooth, pale bark are scars left behind when the tree sheds lower branches that receive less sunlight? Look how this porous watchfulness is directed in our direction, how the forest offers us its attention.Together, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

A Special Bonus EpisodeI’m so grateful to share this bonus episode featuring a special conversation I had last year with my dear friend Mark Jensen. It’s a rare and beautiful exchange that touches on healing, grief, and a mystical connection to the Earth—an invitation to listen and remember what truly matters.In today's episode, I’m joined by Mark Jensen, a seasoned practitioner in the healing arts with 40+ years of experience in vitalistic principled chiropractic, cranial work, myofascial release, plant medicines, Qi Gong and Dao Yin classes, somatic/movement teachings, and Earth-based practices that support a more embodied, connected and healthy life. He operates a private practice, teaches for nonprofits, and leads community classes and ceremonies.Mark's profound understanding and ability to blend mystical visions with scientific study make this conversation a treasure trove of wisdom and inspiration. Mark shares insights from decades of practice in the healing arts, including his conceptualization of the "circle of visions" and how attentional intimacy and communion with life’s intelligence can lead to profound healing. We delve into his deep connection with nature, the power of grief, and transformative experiences in his own healing journey. He also touches on the significance of holding space for joy amidst ecological and societal challenges.Episode HighlightsThe Power of Grief: Mark emphasizes embracing grief as a path to deeper love and soul connection.Ecological Despair and Healing: Insights on navigating ecological despair and finding healing through a greater understanding of the earth's intelligence.Visions and Spiritual Experiences: Mark shares transformative visions and spiritual encounters that have shaped his practice.Holding Dichotomy and Paradox: The importance of balancing the celebration of beauty with the acknowledgment of despair.Connection with Nature: Mark discusses his deep bond with nature and how it has guided and healed him throughout his life.The Role of Fascia in Healing: Insights into how fascia, the body's connective tissue, plays a crucial role in sensing and responding to the world.Community and Shared Grief: Community and shared experiences in processing grief and preventing despair.Mark Jensen“My journey began in Northern Minnesota and has carried me across landscapes, traditions, and thresholds of healing. Though trained in college and graduate school, my true education came from life itself—from births and deaths I was honored to attend, from those who entrusted me with their bodies, and from teachers across disciplines like Osteopathy, Daoism, Chinese Medicine, Herbalism, Deep Ecology, and land-based ceremony. The land has been my greatest teacher—from the plains of Oklahoma to the mountains of New Mexico, and now, back home to the shores of Gichigami (Lake Superior).I live in Duluth, Minnesota with my wife, artist Riha Rothberg, and our cat Gus. I continue to teach healthcare practitioners and maintain a private healing practice rooted in presence, ecology, and transformation.”Resource LinksLearn more about Mark and how to engage in his offerings, courses, and events at marksjensendc.comSubscribe to The Guest House on Substack for regular essays, podcast episodes, and more.Shawnparell.com - Check out Shawn's website to sign up for 5 free meditations, join Shawn’s email list for monthly field notes and music alchemy, and learn more about her work and upcoming events.Stay connected with Shawn on Instagram @ShawnParell for live weekly meditations and prompts for practice. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

Springtime in North Carolina is gorgeous. It can’t help itself. Perhaps it’s oblivious to—or in radical disagreement with—the brokenness of our times. Either way, the azaleas burst into riotous bloom, the crepe myrtles frill themselves in defiant pinks. In the mornings, birds trade secrets across the creek, their calls carried on air perfumed with fresh dew on pine needles to the back porch, where I sit in my mother’s rocking chair.This is the place where one branch of my family has put down roots. An invisible wheel exists here among us, with smaller wheels—wheels within wheels—turning persistently through the seasons. It’s also the place where a beloved uncle passed last autumn, just as the maple outside his bedroom window flared into auburn light. In his final days, we watched that tree together and recounted long-forgotten stories. I remembered a visit to First Street in Rumson, when he swung me onto his shoulders and walked down the street. I remembered how the curves of his shoulders hummed beneath me as he laughed. How tall I felt then, how near to the canopy of trees; how the world suddenly seemed bigger and closer, and I, more a part of it—alive to everything, and everything alive around us.Memory can work like this—the way light filters through leaves or a scent pulls you backward. In a recent conversation with Krista Tippett, musician Justin Vernon (better known as Bon Iver) said, “I thought I was done being surprised… but there are things behind things behind things.” The layers accumulate, folded under the weight of time, only to surface in time, unbidden yet strangely familiar.Now the maple is green again, its leaves doing what they were made to do when touched by springtime light. Its roots drink in a soft rain. Some layers remain hidden, or slip away, only to circle back, as though time itself were not linear, but folding in on itself like fabric. And I think about how you have entered the mystery now, and maybe you are humming in some new, unknowable way.Practice—call it “mindfulness” or whatever name feels right—is an agreement to be touched by the world, by the nature of our aliveness. David Abram called it “a kindredship of matter with itself.” We learn to live in reciprocal communion, even unknowingly, and discover within ourselves gradually more tonality, more steadiness, more truth. When we plant ourselves in this moment, and notice the ways we are thirsty, and then return again and again, we begin to sense that our lives are not just motion or mechanism, but part of some deeper listening—not just hub and spoke, but spiraling motion.Hope, too, is a force of nature. It arrives unannounced. Here’s another chance, another season. The word numinous comes from numen—a Latin term that means both “a nod of the head” and “divine will.” Now spring has found its fulcrum, and with a quiet nod toward resurrection, it invites us to reach for something like joy, whether or not we feel ready or agree with time’s assessment.Springtime is not a promise. It’s a presence. A tilt in the wheel. A shimmer in the unseen. A reminder that aliveness is not always sweet or simple—but it is, still, ours.Together, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

Today is the Vernal Equinox. We’re promised incremental victories of light. But early spring is no darling — not here in the high desert. Here, she can be chafing and mercurial; she can show up in sputtering, immature fits and freezes; in mean winds that would cut down the most tender and flower-faced among us without reason.Earlier this week, the sky howled and turned the color of mud at mid-day. Cell phones blared out public safety warnings. Dust agitated at every seam.What’s a nervous system to do? Have mercy on the tender-hearted, Lord — on the dream of apricots and cherries, and the boy at school pickup who is rubbing and rubbing his nose against the back of his chapped hand.Like you, I am learning to find refuge. I am learning to take shelter in the soft aliveness of my body; remembering in adulthood what came so easily and imaginatively to my younger self — how to build a fort, how to tuck into a small world of my own making.So, I gather a reading light, a ball of yarn, knitting needles, and a poetry collection, and I tent a wool blanket over my head to hole up for the duration.One thing I know for sure is how a poem can serve like the keel of a boat, offering stability and resistance against sideways forces. A poem — a few words that, when linked together at an angle just so, can carry us into and beyond their meaning. And so it is with this needfulness, under a blanket in my living room, that I come to Wordsworth’s “Lines Written in Early Spring,” a meditation he wrote in 1798 on the joyful, interwoven consciousness of nature — a “thousand blended notes” of birdsong — and humanity’s grievous failure to remember its place under the canopy of all things.In the grove where the speaker sits, twigs “spread out their fan,” flowers “enjoy the air,” and Nature, personified, is a force with a “holy plan.” But human beings, the speaker laments, have lost the splendrous sensibilities of spring: “If such be Nature’s holy plan / Have I not reason to lament / What man has made of man?”It occurs to me that man has done many good things with his hands. I am thinking now of a live performance of Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2, or the sweater that Wendy-from-the-yarn-shop just masterfully knitted, or the perfectly packaged mini-waffles my friend Ted brought back from a recent trip to Japan.But much of the time, we get things at least half-wrong. Like seed-creatures, we struggle to find our way upward through hard ground. We move too quickly, unaware of our conditions, and make mistakes. We forget to pause and remember the purpose of our unearthing. And we forget the interweave, the garden of our original belonging.So, I’m teaching myself how to knit. Novice that I am, it’s awkward work. It’s near-in. I tink (a new word for me, a semordnilap that refers to the act of un-stitching) almost as often as I knit. I struggle to position my hands, to maintain the right angle, I poke around and lose count and then I have to begin again.And in all this seeming progress and unraveling, as I return to mistakes embedded long ago, a new pattern — peaceful and even elegant — is steadily emerging. Oh, nervous system, dear friend. I am un-stitching and stitching myself back together again. I am braiding threads of myself into an artwork of my own making, which is weaving me back into something greater than my own making. And when the thing is ready, I will hold it up in wonder. I will hold it to my cheek.Together, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

Found amidst the twisted metal and ash of a family’s home in the Pacific Palisades is a pottery shard with a single word inscribed upon it: love.It’s a clay piece no wider than the palm of your hand, a remnant from a serving dish that a daughter made for her mother, who displayed it in the bungalow where she lived for forty-seven years until one recent day when a black-plumed terror tore through the neighborhood, and it burned to the ground.For Diana, the one who first taught me how to love. Thank you, Mama. Happy Mother’s Day, 2011. Your loving daughter, Lisa.Little remains after a fire. Not the for nor the who nor even the you. In the yard, a wind sculpture spirals upward in the stunned calm of a new day. Stone chimneys stand, only they are no longer chimneys but landmarks by which neighbors orient themselves amidst the rubble and scars of their former lives. A clay murti still sits demurely on the mantle. It is a metaphor, if not a miracle — how the heat melted away its glaze and revealed the form beneath.And love, in all its blessed unlikeliness. Having passed through the inferno of its creation, having withstood as the house wailed and collapsed around it, this small and necessary gift is discovered atop a charred pyre as though placed there, liberated, message intact.City skies are painted on linear scraps and framed by buildings. The desert sky is like this: giant, unmitigated, persistent. To live well in the desert, you must look to the opening above the narrow frame of your life. You must consider how light moves across the sky, how gods shift their bodies over the landscape, then bow and tuck themselves behind the night until the sun rises again the next day.Azure is beautiful but can also be unyielding. The earth firms and softens according to the seasons. Slow water eases; gentle water eases. Fast water flashes off the hard earth and floods the arroyos. And if the water does not come — if the days are brittle and the future unknowable — we are thirsty for it.When the ground dries, we feel it in our joints. The sky lifts — quiet, strange. We ask for water. Lord, quell our bodies and minds. Lord, irrigate our hearts. Lord, make us watertight.Then, the birds come looking for water. We give them water.Mary Oliver writes:I tell you thisto break your heart,by which I mean onlythat it break open and never close againto the rest of the world.A poet finds a way to say what must be said when it must be said. A poet is made of poppies and daffodils, yes, but also of unflinching metal. Forged in fire, quenched in water, a poet is like a sword meant to wield, cut through, and rise again.Metal cannot help but conduct warmth. Metal cannot help but have luster, for it reflects the sun's light. Metal has solidity, a high melting point, and sharpness. It houses its own shadow, like most earthly things. So, when metal writes about lead, it knows a thing about it. And when metal says —Here is a story to break your heart.Are you willing?You are willing.Steadfast comes from the Old English stedefæst, meaning "firmly fixed, constant; secure; enclosed, watertight; strong, fortified." It first referred to English warriors in the 10th century who stood their ground, weapons readied, unyielding to Viking invaders.And here is one more reminder of the determination of love. In Portuguese, the word resistencia is a false cognate. You’d think it means resistance, but no — resistencia is closer to endurance, to the practice of withstanding. Resistencia refers to that which is unbreakable.To endure is to show up in the ways that most reflect who we are and what we love, to continually orient ourselves, even amidst circumstances we would not choose. When the instinct is to burn, to endure is to carry water instead.Become a paid subscriber for $6/month to access monthly yoga + meditation practices exclusively for The Guest House community. Practices live or via recording at your convenience. Next gathering soon to be announced! This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

STEADFAST(Inspired by Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer’s “Wordlessly”)The way the pericardium holds the heart,the pond holds the murk, and fish,the bowl holds the porridge my child eatsits steam rising to hold her face —and morning cups the day,the way day cups the nightin a great, persistent mystery, the socket holds the gaze.your palm holds my hand, your silence holds, “I’m here” — our bodies hold the ache of how the world could be, how the world could be holding how it is.- Shawn ParellTogether, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

Dear friend,I’m writing today from a quiet harbor in the West Indies where, for the past few years, my family has come to rest during the liminal week between Christmas (or this year's portmanteau, Christmukkah) and New Year’s.In the final days of 2023, in an essay about thresholds and time, I described an overlook I like to walk to here on the island of Grenada — a cliff at the top of a grassy knoll from which water shimmers into a circular horizon. So much has changed since then, a reminder of how the business of time is to change.If I could, I would tie the gentleness of this place with silk ribbon and dispatch it across the sea in every direction. Nearby, a kindly breeze rocks a resting child in her hammock. My father whispers in my son's ear, laughter buoying up from their bellies as kids scamper barefoot across the thick green lawn and a pot of fresh mint tea rests on the table, its fragrant steam unfurling in the air.In this place of warbling, white-breasted flycatchers and shading palm fronds, of lilting afternoon voices filtering through muslin curtains, a certain fatigue I can no longer ignore lays its hands calmly on my shoulders. For months, I’ve been brushing aside signals of this heavy tenderness, but now my mind and body settle into them. I begin to wonder about the texture and tone of this fatigue, about its intentions and layers and causes. I watch a ripening calabash tree and imagine what it might feel like — not good, not bad, but simply laden.I am beginning to re-learn the science and art of rest. I get slower and quieter, simplifying my days by shoring up against the instinct to do, fill, get, and rush. I visualize silk-ribboned gentleness delivered by tiny boats of breath to my nervous system. My mind loosens, and I remember a childhood lesson from my father, who has spent most of his days on or by the ocean, on re-finding equilibrium when feeling sea-rattled: relax as much as possible, breathe deep, and fix your gaze on the horizon, kiddo.And gradually, my bones begin to feel their weight again.How many of us carry a quiet knowing, unnoticed or avoided, until stillness brings it into view?My mind drifts to “The World," a poem by William Bronk that my friend Jess Lazar introduced to me this past year.I thought you were an anchor in the drift of the world;but no: there isn’t an anchor anywhere.There isn’t an anchor in the drift of the world. Oh no.I thought you were. Oh no. The drift of the world.—The WorldIt is a sorrowful, even devastating poem, but Bronk’s revelation also carries benevolence. The brimming honesty of “I thought you were...” “but no” reflects and comforts my grappling at the precipice of this new year. Truth be told, I have moved between hope and apprehension, promise and disappointment, acceptance and fear — and it’s exhausting. I’m learning to find a more nuanced, intentional way of leveling my gaze amidst the world's drift.“The World” is hopeful insofar as its author reaches outside the confines of his one lonely boat to connect with us, his readers. The drift of the world is unrelenting and amoral, he intimates. We are human and, therefore, subject to attachments, grievances, foolishness, and all the rest. Our anchors moor us in their brevity, and our lives, too, shimmer with wakefulness. It’s all so precious and immutable, yet we can tap into unexpected harbors and safe ports, not despite but because of and given the facts.Rumi reminds us, “Your deepest presence is in every small contracting and expanding, the two as beautifully balanced and coordinated as birds’ wings.” We are of the nature to wake up. We are of the nature to let go. “I thought you were an anchor in the drift of the world; but no….” Looking out over azure water, I’m reminded of how life emerges and regenerates from these tidal rhythms — we expand, we contract, an ocean falling and rising again from within.Together, we are making sense of being human in an era of radical change. Your presence here matters. Thank you for reading, sharing, ‘heart’ing, commenting, and subscribing to The Guest House. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

In this insightful conversation, I’m joined by poet James Pearson to explore personal growth, vulnerability, and the creative process. The discussion centers on themes of transformation, wholeheartedness, and navigating life’s difficult "winter seasons," a metaphor for the times of struggle, uncertainty, and rebirth. Pearson shares personal stories from his journey of self-discovery and healing, including the moments of asking for help that led to unexpected lifelines. Together, we delve into the wisdom found in nature's cycles and the power of messy, in-between times for personal growth.James reflects on his poetic work, particularly his debut collection The Wilderness That Bears Your Name. We discuss the idea of being "mirrored into existence" and the importance of human connection in helping us see and embrace our true selves. This conversation is both a meditation on the cyclical nature of life and an invitation to make room for uncertainty.Episode Highlights:* Wholeheartedness: The challenge of connecting to wholeheartedness during difficult, desolate times, and the courage it takes to ask for help.* Unordinary Emergence: Inspired by David Whyte’s concept of the hidden essence within us that emerges when we are invited and supported.* Mirroring and Connection: The importance of being "mirrored into existence" through human relationships and how communal reflection shapes our sense of self.* The Mud Season: The metaphorical season between winter and spring, where growth is messy but crucial.* Nature’s Lessons on Transformation: Lessons from Parker Palmer and Richard Rohr on the humility and grace found in life's messy, humbling experiences.* Reclaiming Authenticity: Facing existential crises and shedding old identities to make space for more authentic versions of ourselves.* Seeing Beauty in the Mess: Reflections on how even life’s "weeds" and imperfections hold beauty and significance.This episode is an invitation to embrace life's muddy seasons with patience, courage, and the willingness to see possibility in the mess.* Learn more about James and The Wilderness That Bears Your Name at Jamesapearson.com.* Connect with James on Instagram: @Jamesapearson* Subscribe to The Guest House on Substack for regular essays, podcast episodes, and more.* Shawnparell.com - Check out Shawn's website to sign up for 5 free meditations, join Shawn’s email list for monthly field notes and music alchemy, and learn more about her work and upcoming events.* Stay connected with Shawn on Instagram @ShawnParell for live weekly meditations and prompts for practice.* Join David Keplinger and me on January 24-25, 2024, for Mary Oliver and the Quest of Openness: "Are You Willing"?—a yoga, meditation, and somatic inquiry workshop hosted by YogaSource in Santa Fe. Drawing on his many years of friendship with Mary Oliver, David will help us explore themes of openness and willingness in her poetry. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe

In this deeply moving episode of The Guest House, I sit down with artist and trained therapist Caitlin Rhoades to explore the intricate landscape of grief and death. Through her own experience of compound loss, Caitlin reveals how grief reshapes our lives, teaching us about love, resilience, and the priorities that truly matter. Together, we navigate the societal discomfort surrounding death, the somatic experience of grief, and the transformative power of facing mortality with openness and inquisitiveness.Whether you’re grieving a loved one, supporting someone through loss, or seeking a deeper comprehension of life’s impermanence, this conversation offers profound insights and actionable wisdom for embracing grief as a natural part of the human journey.Episode Highlights:Grief is universal: It’s not limited to the loss of a loved one but encompasses daily and situational losses.The physical impact of grief: Unprocessed grief can manifest in the body, requiring mindful approaches to healing.The need for cultural change: Open discussions about death can dismantle societal discomfort and deepen life’s appreciation.Grief’s nonlinear journey: Every experience of grief is unique, defying a prescriptive process.Support through presence: Authentic engagement with grievers means meeting them where they are, without judgment or quick fixes.Transformative potential of grief: Loss can deepen love, joy, and life’s clarity when approached with courage and intention.Creating space for grief: Normalizing conversations and providing safe environments for emotional expression is vital.Join us to explore how grief can be a powerful teacher and connector. Reflect on your own relationship with loss, and consider initiating meaningful conversations about death with your loved ones. Please subscribe, leave a review, and share this episode with anyone who might find comfort or insight in these reflections.Resource LinksYou can learn more about Caitlin’s work and ways to work with her at caitlinrhoades.com.Follow Caitlin on Instagram @caitlinrhoadesceramics.Check out the Getting Your Affairs in Order Checklist: Documents to Prepare for the Future from the National Institute on Aging.Subscribe to The Guest House on Substack for regular essays, podcast episodes, and more.Shawnparell.com - Check out Shawn's website to sign up for 5 days of free meditations, join Shawn’s email list for field notes and music alchemy, and learn more about her work and upcoming events.Stay connected with Shawn on Instagram @ShawnParell for live meditations and prompts for practice.I'm delighted to invite you to Gathering at the Hearth, a winter retreat in the Rockies co-led with Wendelin Scott, this February 21-24, 2025. Join us at Beyul Retreat near Aspen, Colorado, for a weekend of yoga, meditation, and rest in a serene, snow-covered sanctuary. Cozy cabins, crackling fireplaces, and nourishing practices await—space is limited, so reserve your spot today! Discounted rates when you sign up with a friend.Subscribe to The Guest House and never miss an episode filled with stories and insights that inspire, connect, and empower. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit shawnparell.substack.com/subscribe