Discover Elephant Island Chronicles

Elephant Island Chronicles

Elephant Island Chronicles

Author: Gio Marron

Subscribed: 0Played: 1Subscribe

Share

© Gio Marron

Description

Welcome to a world where stories unfold in myriad hues and forms. Gio Marron's Fiction Hub is a Substack sanctuary dedicated to celebrating fiction in all its diverse glory.

What Awaits You Here:

A Spectrum of Stories: Whether it's the rhythmic pulse of

giomarron.substack.com

What Awaits You Here:

A Spectrum of Stories: Whether it's the rhythmic pulse of

giomarron.substack.com

76 Episodes

Reverse

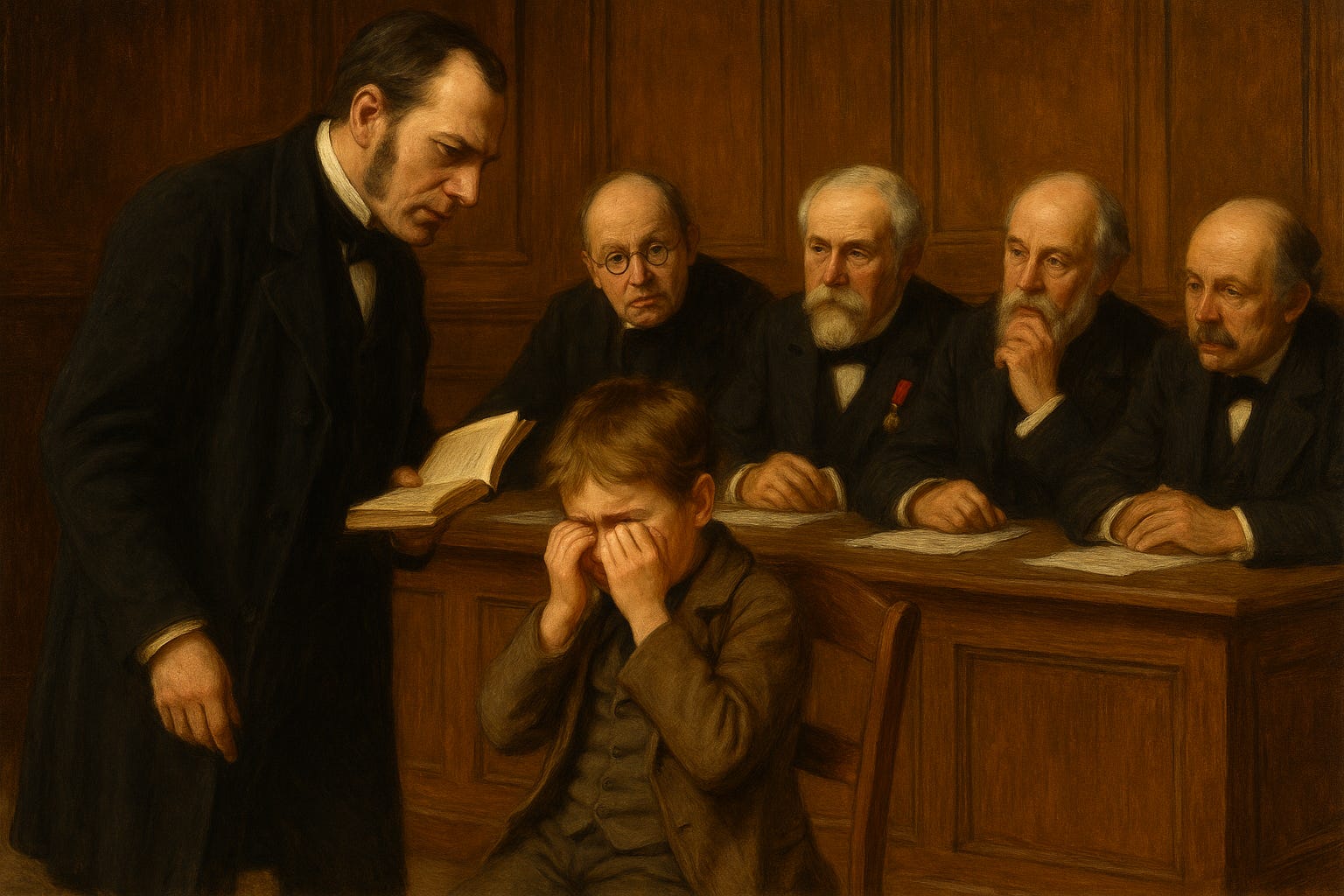

The Elephant Island ChroniclesPresentsThe Question Of Latinby Guy de MaupassantTranslated by ALBERT M. C. Mcmaster, B.A.; A. E. HENDERSON, B.A.; MME. QUESADA And OthersNarration by Eleven LabsForward by Gio MarronForewordIn The Question of Latin, Guy de Maupassant turns his sharp satirical eye toward the rigid structures of classical education and the bureaucracies that uphold them. Written during a period when Latin was still considered the pinnacle of academic achievement in French schools, the story exposes the absurd lengths to which educational authorities will go to preserve appearances, even in the face of failure.What unfolds is not just a critique of outdated pedagogy, but a broader indictment of a system more concerned with optics than with learning. The child's inability to answer a question becomes less important than the officials’ eagerness to reframe ignorance as virtue. Maupassant, with characteristic irony, reveals how social prestige, institutional pride, and empty decorum often conspire to obscure truth.Though specific in its cultural setting, the story remains strikingly relevant today—as debates over educational relevance, performance-based evaluation, and institutional credibility continue. This brief tale reminds us that the true farce is not ignorance itself, but the elaborate fictions we create to conceal it.Gio MarronThe Question Of Latinby Guy de MaupassantTranslated by AlbertM. C. Mcmaster, B.A.; A. E. Henderson, B.A.; MME. Quesada And OthersThis subject of Latin that has been dinned into our ears for some time past recalls to my mind a story—a story of my youth.I was finishing my studies with a teacher, in a big central town, at the Institution Robineau, celebrated through the entire province for the special attention paid there to the study of Latin.For the past ten years, the Robineau Institute beat the imperial lycee of the town at every competitive examination, and all the colleges of the subprefecture, and these constant successes were due, they said, to an usher, a simple usher, M. Piquedent, or rather Pere Piquedent.He was one of those middle-aged men quite gray, whose real age it is impossible to tell, and whose history we can guess at first glance. Having entered as an usher at twenty into the first institution that presented itself so that he could proceed to take first his degree of Master of Arts and afterward the degree of Doctor of Laws, he found himself so enmeshed in this routine that he remained an usher all his life. But his love for Latin did not leave him and harassed him like an unhealthy passion. He continued to read the poets, the prose writers, the historians, to interpret them and penetrate their meaning, to comment on them with a perseverance bordering on madness.One day, the idea came into his head to oblige all the students in his class to answer him in Latin only; and he persisted in this resolution until at last they were capable of sustaining an entire conversation with him just as they would in their mother tongue. He listened to them, as a leader of an orchestra listens to his musicians rehearsing, and striking his desk every moment with his ruler, he exclaimed:“Monsieur Lefrere, Monsieur Lefrere, you are committing a solecism! You forget the rule.“Monsieur Plantel, your way of expressing yourself is altogether French and in no way Latin. You must understand the genius of a language. Look here, listen to me.”Now, it came to pass that the pupils of the Institution Robineau carried off, at the end of the year, all the prizes for composition, translation, and Latin conversation.Next year, the principal, a little man, as cunning as an ape, whom he resembled in his grinning and grotesque appearance, had had printed on his programmes, on his advertisements, and painted on the door of his institution:“Latin Studies a Specialty. Five first prizes carried off in the five classes of the lycee.“Two honor prizes at the general examinations in competition with all the lycees and colleges of France.”For ten years the Institution Robineau triumphed in the same fashion. Now my father, allured by these successes, sent me as a day pupil to Robineau's—or, as we called it, Robinetto or Robinettino's—and made me take special private lessons from Pere Piquedent at the rate of five francs per hour, out of which the usher got two francs and the principal three francs. I was then eighteen, and was in the philosophy class.These private lessons were given in a little room looking out on the street. It so happened that Pere Piquedent, instead of talking Latin to me, as he did when teaching publicly in the institution, kept telling me his troubles in French. Without relations, without friends, the poor man conceived an attachment to me, and poured out his misery to me.He had never for the last ten or fifteen years chatted confidentially with any one.“I am like an oak in a desert,” he said—“'sicut quercus in solitudine'.”The other ushers disgusted him. He knew nobody in the town, since he had no time to devote to making acquaintances.“Not even the nights, my friend, and that is the hardest thing on me. The dream of my life is to have a room with my own furniture, my own books, little things that belong to myself and which others may not touch. And I have nothing of my own, nothing except my trousers and my frock-coat, nothing, not even my mattress and my pillow! I have not four walls to shut myself up in, except when I come to give a lesson in this room. Do you see what this means—a man forced to spend his life without ever having the right, without ever finding the time, to shut himself up all alone, no matter where, to think, to reflect, to work, to dream? Ah! my dear boy, a key, the key of a door which one can lock—this is happiness, mark you, the only happiness!“Here, all day long, teaching all those restless rogues, and during the night the dormitory with the same restless rogues snoring. And I have to sleep in the bed at the end of two rows of beds occupied by these youngsters whom I must look after. I can never be alone, never! If I go out I find the streets full of people, and, when I am tired of walking, I go into some cafe crowded with smokers and billiard players. I tell you what, it is the life of a galley slave.”I said:“Why did you not take up some other line, Monsieur Piquedent?”He exclaimed:“What, my little friend? I am not a shoemaker, or a joiner, or a hatter, or a baker, or a hairdresser. I only know Latin, and I have no diploma which would enable me to sell my knowledge at a high price. If I were a doctor I would sell for a hundred francs what I now sell for a hundred sous; and I would supply it probably of an inferior quality, for my title would be enough to sustain my reputation.”Sometimes he would say to me:“I have no rest in life except in the hours spent with you. Don't be afraid! you'll lose nothing by that. I'll make it up to you in the class-room by making you speak twice as much Latin as the others.”One day, I grew bolder, and offered him a cigarette. He stared at me in astonishment at first, then he gave a glance toward the door.“If any one were to come in, my dear boy?”“Well, let us smoke at the window,” said I.And we went and leaned our elbows on the windowsill looking on the street, holding concealed in our hands the little rolls of tobacco. Just opposite to us was a laundry. Four women in loose white waists were passing hot, heavy irons over the linen spread out before them, from which a warm steam arose.Suddenly, another, a fifth, carrying on her arm a large basket which made her stoop, came out to take the customers their shirts, their handkerchiefs, and their sheets. She stopped on the threshold as if she were already fatigued; then, she raised her eyes, smiled as she saw us smoking, flung at us, with her left hand, which was free, the sly kiss characteristic of a free-and-easy working-woman, and went away at a slow place, dragging her feet as she went.She was a woman of about twenty, small, rather thin, pale, rather pretty, with a roguish air and laughing eyes beneath her ill-combed fair hair.Pere Piquedent, affected, began murmuring:“What an occupation for a woman! Really a trade only fit for a horse.”And he spoke with emotion about the misery of the people. He had a heart which swelled with lofty democratic sentiment, and he referred to the fatiguing pursuits of the working class with phrases borrowed from Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and with sobs in his throat.Next day, as we were leaning our elbows on the same window sill, the same woman perceived us and cried out to us:“Good-day, scholars!” in a comical sort of tone, while she made a contemptuous gesture with her hands.I flung her a cigarette, which she immediately began to smoke. And the four other ironers rushed out to the door with outstretched hands to get cigarettes also.And each day a friendly intercourse was established between the working-women of the pavement and the idlers of the boarding school.Pere Piquedent was really a comical sight. He trembled at being noticed, for he might lose his position; and he made timid and ridiculous gestures, quite a theatrical display of love signals, to which the women responded with a regular fusillade of kisses.A perfidious idea came into my mind. One day, on entering our room, I said to the old usher in a low tone:“You would not believe it, Monsieur Piquedent, I met the little washerwoman! You know the one I mean, the woman who had the basket, and I spoke to her!”He asked, rather worried at my manner:“What did she say to you?”“She said to me—why, she said she thought you were very nice. The fact of the matter is, I believe, I believe, that she is a little in love with you.” I saw that he was growing pale.“She is laughing at me, of course. These things don't happen at my age,” he replied.I said gravely:“How is that? You are all right.”As I felt that my trick had produced its effect on him, I did not press the matter.But every day I pretended that

Voice-over provided by Eleven Labs or Amazon PollyThe Cipher of Rue RoyalA Mimi Delboise MysteryBy Gio MarronThe brass nameplate on the door read "M. Delboise, Private Detective" in letters that caught the morning light filtering through the French Quarter's narrow streets. Mimi Delboise adjusted the tilt of her hat and checked her pocket watch—eight-thirty sharp. Punctuality was a virtue she demanded of herself, if not always of her clients.The woman waiting in her small office was clearly nervous, her gloved hands worrying the clasp of an expensive leather purse. She couldn't have been more than twenty-five, with the pale complexion of someone who spent little time in New Orleans' unforgiving sun. Her dress was fashionable but not ostentatious—the carefully calculated appearance of new money trying not to appear too eager."Mrs. Boudreaux, I presume?" Mimi settled behind her desk, noting how the woman's eyes darted to the window overlooking Royal Street before returning to meet her gaze."Yes, though I... I wasn't certain you would see me. Some of the ladies at the Literary Society suggested that perhaps a woman inquiry agent might not be... suitable for such matters."Mimi had heard variations of this conversation many times. She leaned back in her chair, allowing a slight smile to play at the corners of her mouth. "And yet here you are. Which suggests your need outweighs your social circle's reservations."A flush crept up Mrs. Boudreaux's neck. "My husband is receiving threatening letters. The police dismiss them as pranks, but..." She reached into her purse and withdrew a folded paper. "This arrived yesterday."Mimi accepted the letter, immediately noting the quality of the paper—expensive but not the finest available. The handwriting was educated, with the slight flourishes suggesting European training, but something was deliberately theatrical about the script.Your accounts must be settled before the moon wanes, or your secrets will illuminate the shadows where your reputation now hides."Cryptic," Mimi observed, turning the paper to examine the watermark. "But not particularly threatening. Has your husband any idea what accounts might be referenced?""He claims ignorance entirely. Says it's merely some competitor trying to unnerve him before the cotton exchange votes on new regulations." Mrs. Boudreaux's voice carried the careful neutrality of a wife who had practiced believing her husband's explanations."But you suspect otherwise.""I suspect my husband keeps ledgers I've never seen." The admission came quietly, followed by a quick glance toward the door as if Gabriel Boudreaux might materialize to overhear his wife's disloyalty.Mimi studied the young woman's face, noting the faint shadows beneath her eyes that suggested sleepless nights. "Mrs. Boudreaux, before we proceed, I must ask—are you prepared for the possibility that your suspicions may prove correct? My investigations have a tendency to uncover truths that clients sometimes wish had remained buried."The silence stretched between them, filled with the distant sounds of the French Quarter awakening—street vendors calling their wares, the clip-clop of horses on cobblestones, the musical cadence of Creole French drifting through the open window."I need to know," Mrs. Boudreaux said finally. "Whatever it is, I need to know."Two hours later, Mimi stood in the shadow of the Cabildo, watching the morning's commerce unfold in Jackson Square. The letter had yielded several clues to someone trained in observation: the particular shade of blue ink suggested a specific type of pen, likely German-made and expensive. The paper's watermark belonged to a shop on Royal Street that catered to the city's more discerning letter-writers. Most intriguingly, the phrasing carried the careful cadence of someone whose first language was not English—French, most likely, though she detected hints of Spanish influence in the sentence structure.The watermark led her first to Papeterie Dubois, a narrow shop squeezed between a millinery and a dealer in rare books. The proprietor, Monsieur Dubois, was an elderly Creole gentleman whose careful manners barely concealed his assessment of Mimi's unconventional appearance."Bonjour, Madame. You inquire about our correspondence papers?"Mimi produced the letter, keeping the text carefully folded away. "This particular stock. Do you recall who might have purchased it recently?"Dubois examined the paper with the solemnity of a wine connoisseur evaluating a vintage. "Ah, yes. Our finest grade. We sell perhaps twenty sheets per month of this quality." He paused, his eyes meeting hers. "You are investigating some matter of consequence?""A private matter for a client. Nothing that need concern the authorities." The assurance seemed to ease his reluctance."There have been three purchases this month. Madame Thibodaux for her weekly correspondence with her sister in Baton Rouge—but she has used this paper for twenty years, since her dear husband's passing. Monsieur Beauregard purchased two packets last week, but his secretary collects his supplies on the fifteenth of each month, regular as clockwork.""And the third?""A gentleman I did not recognize. Well-dressed, spoke French with an accent I could not place. Perhaps from the islands? He purchased only one packet, paid in cash, and seemed... nerveux. Nervous, you understand."Mimi nodded, filing away the description. "When was this?""Voyons... three days ago. Tuesday morning, just after we opened."Tuesday. The same day the first letter had arrived, according to Mrs. Boudreaux. The timing was too convenient to be coincidence.Her next stop took her deeper into the Vieux Carré, to a café on Chartres Street where she had arranged to meet Marie Trosclair. Marie operated a small but successful dressmaking establishment and, more importantly for Mimi's purposes, possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of the Quarter's gossip networks."Chère Mimi," Marie called out as she approached the small table tucked into the café's courtyard. "You look like a woman with questions that need answers."Mimi settled into the wrought-iron chair, grateful for the shade provided by the ancient oak tree that dominated the courtyard. "When do I not? What do you know about Gabriel Boudreaux?"Marie's eyebrows rose slightly. "The cotton factor? New money, from up north somewhere. Married that pretty Treme girl—Céleste—last spring. Big wedding at the Cathedral, reception at the St. Charles Hotel." She paused, sipping her café au lait. "Why do you ask?""Professional curiosity. Has he any particular enemies? Business rivals who might wish him ill?""Mais non, nothing like that. Though..." Marie leaned forward, lowering her voice despite the courtyard's relative privacy. "I heard from Madame Reeves, who does alterations for some of the American wives, that he's been seen at Baccarat Bob's establishment rather frequently."Mimi knew the name—Robert Baccarat ran one of the Quarter's more exclusive gambling houses, catering to gentlemen who could afford to lose substantial sums without damaging their social standing. "Recently?""The past month or so. And you know what they say about cotton factors and gambling debts."Indeed she did. The cotton trade was notoriously volatile, fortunes made and lost on the fluctuations of global markets. A man facing significant gambling debts might find himself making increasingly desperate financial decisions."Marie, have you heard anything about someone new in the Quarter? A gentleman, well-dressed, speaks French with an island accent?"Marie considered this, tapping one finger against her cup. "There's been talk of a Haitian gentleman staying at the Pension Marigny. Calls himself Monsieur Dubois—no relation to the paper seller, I assume. Keeps to himself mostly, pays his bills promptly. Madame Marigny says he's been here about two weeks."The pieces were beginning to form a picture, though Mimi suspected the complete image would prove more complex than these initial fragments suggested.The Pension Marigny occupied a corner lot on Ursulines Street, its Creole cottage architecture typical of the Quarter's residential buildings. Madame Marigny herself answered Mimi's knock—a woman of indeterminate age whose sharp eyes suggested she missed little of what transpired in her establishment."I'm inquiring about one of your guests," Mimi began, presenting her card. "A Monsieur Dubois?"Madame Marigny examined the card with the same attention she might give a suspicious bank note. "You are an inquiry agent, vraiment? A woman detective?" The concept seemed to both surprise and intrigue her."I am investigating a matter involving threatening letters. Nothing that reflects poorly on your establishment, I assure you."This seemed to satisfy her concerns about propriety. "Monsieur Dubois has been a model guest. Quiet, courteous, pays in advance. He keeps regular hours—leaves each morning after breakfast, returns before dinner.""Has he received any visitors? Or sent any correspondence?""No visitors that I've observed. As for correspondence..." She paused, clearly weighing discretion against curiosity. "He did ask about a reliable messenger service yesterday. Said he had several letters to deliver but preferred not to entrust them to the postal service."Another piece fell into place. "Did he say anything about the nature of these letters?""Only that they concerned debts of honor. I assumed he meant gambling debts—such things are common enough among gentlemen of a certain class."Mimi thanked Madame Marigny and made her way back toward the river, her mind working through the connections she had uncovered. A Haitian gentleman with access to expensive paper, sending letters about debts to Gabriel Boudreaux, who had been frequenting the city's gambling houses. The outline of the situation was becoming clearer, but several crucial questions remained unanswered.Baccarat Bob's establishment occupied the upper floors of a building on Roya

Three Miles OutBy Gio MarronVoice-over provided by Eleven Labs The ShipThe USS Theodore Roosevelt dropped anchor three miles off the coast of Virginia, hull cutting a stark silhouette against the dawn sky. Not far enough to forget land, not close enough to touch it. Virginia Beach shimmered on the horizon like a mirage—real, but out of reach. Petty Officer Third Class Michael Reese stood motionless at the port side rail, the salt-heavy air filling his lungs after months of desert sand.The Hopeful Voice: He stood at the rail in the pale light of early morning, watching the coastline sharpen as the day began. Home. Not metaphorical—actual, American home. The scent of boardwalk fries and saltwater taffy seemed to drift across the water. That was the moment. The crossing back. Six months of carrier ops in the Persian Gulf dissolved into this single point of return. He'd made it. The war was behind him now, three miles of calm water separating then from now.The Realist Voice: No, it wasn't a return. It was a holding pattern. A bureaucratic pause designed by people who'd never had to wait. Like someone put a bookmark in his life and forgot to come back to it. The ship hung in the water like a question with no answer—not there, not here. Just suspended. The land looked almost painted onto the horizon, unreal and mocking.He counted jet skis, speedboats, gulls. Anything that moved. Everything moved—except the ship. Fifteen jet skis. Twenty-three gulls. Four fishing boats. He counted because counting was control, and control was all he had left."Hey, Reese," someone called behind him. Collins approached, that familiar half-smile on his face. "Beautiful view, right? Almost like we're home.""Almost," Reese replied, the word hollow.Collins leaned against the rail. "I could make that swim," he said, nodding toward shore. "Bet you fifty I could make that swim.""Save your money, Collins." Reese managed a short laugh but it wasn't funny. Nothing about being stuck in sight of home was funny.The Hopeful Voice: He imagined the swim. Not as escape—but arrival. A baptism, almost. A way to feel the distance with his body instead of pretending it didn't matter. He'd done tougher swims in training. Three miles was nothing compared to what he'd already accomplished. He'd cut through the water, each stroke carrying him closer to solid ground, to reality, to a life where the horizon didn't always hide threats.The Realist Voice: He imagined the swim because it was the only way he could believe he'd ever reach shore. The Navy had brought him to war and nearly brought him back—but not all the way. Three miles might as well have been three hundred. The water between ship and shore wasn't just water—it was time, it was protocol, it was everything that separated what he'd become from what he'd been. And nobody was building a bridge across that gap.The Hopeful Voice: Of course they'd notice if he tried. You don't just slip off a carrier unnoticed. The watch would spot him. They'd probably laugh, understand the impulse. Maybe even cheer him on a little before fishing him out. The guys in his division would never let him hear the end of it— "Remember when Reese tried to swim home?"—but it would be a good story. Something to tell at reunions.The Realist Voice: But would they stop him? Or would they just watch, the way everyone watches everything out here—with detached professional interest, marking coordinates, reporting position, never actually engaging. He knew the regs better than most. Man overboard. Full stop. Retrieval protocols. But he wondered sometimes if anyone would really care beyond the paperwork it would generate.He stayed there a long time, gripping the rail like it held him to the world, the metal warm under his palms. He told himself he was just watching the coastline wake up. He told himself he wasn't angry. He told himself a lot of things.The Hopeful Voice: He'd come back changed. Everyone says that about deployment. But really—he'd just come back aware. Aware of the absurdity of time and distance. Aware of how much he'd taken for granted before. Aware of the nearness of things, and how unreachable they could still be. It was a good kind of awareness—the kind that made you appreciate small moments. The kind that would make civilian coffee taste better, civilian beds feel softer.The Realist Voice: He came back knowing the war would always arrive faster than the welcome. That's what they didn't tell you in the recruitment office or the deployment briefs. They talked about readjustment periods and decompression time. They didn't mention the way the world splits into before and after, or how sometimes you get stuck in the space between, watching both sides from a distance. They didn't tell you that coming home was its own kind of deployment—uncertain, dangerous in ways you couldn't prepare for.Pier, No TrumpetsThey finally brought the ship in two days later. Norfolk Naval Station, Pier 12 North. The gangway lowered with the usual hydraulics and yelling, nothing ceremonial about it. The Chief bellowing orders. Sailors in dress whites scrambling to make fast the lines. It was bright, stupidly bright. Concrete and sea spray and sun in his eyes. And people—God, so many people crowded against the barriers, a wall of color and noise after months of khaki and steel.The Hopeful Voice: They came for their sons, husbands, brothers, and fathers. The crowd waited like something sacred was about to happen. Balloons twisted in the breeze. Camcorders catching every moment. Some of the signs had glitter on them, sparkling in the morning light—"Welcome Home Daddy," "My Hero Returns," "Finally Complete Again." People whooped when the first sailors hit the pier, a sound of pure joy that seemed to lift everyone higher. This was what homecoming looked like. This was the moment they'd all dreamed about during midnight watches and long deployments.The Realist Voice: Not for him. There was no sign. No one waiting. Just a wall of other people's joy that he had to navigate through, shoulders squared, eyes forward. He scanned the crowd anyway. Some reflex you can't turn off, like checking corners when you enter a room or counting exits in a restaurant. But there was nothing to find. No familiar face in the sea of strangers celebrating reunions that weren't his."Heading straight out, Reese?" Lieutenant Jameson stopped beside him, sea bag in hand."Yes, sir. Flight leaves in three hours."The Lieutenant nodded. "Good deployment, Reese. Get some real rest.""Thank you, sir." The brief exchange felt both normal and strange—like speaking a language he was rapidly forgetting.He adjusted his cover, slung his sea bag over his shoulder, and walked. One foot after another. Move tactically through the minefield of embracing couples and crying children. Don't make eye contact. Don't get caught in someone else's moment.The Hopeful Voice: He was tired, yes. But not broken. He'd done his part—six months of catapult launches, mine watches, midnights in full gear for drills that always felt a little too real. One hundred and twelve days without setting foot on solid ground. He didn't need a parade. Just a cab and a bed and maybe a beer that hadn't been stored in a ship's hold. He'd earned that much, at least. And there was something dignified about walking off alone, handling his own homecoming in his own way.The Realist Voice: He needed something. Someone to say, "There you are." Someone to look like they'd been watching the horizon for him every day since he left. But the crowd opened around him like he wasn't there. He was just another uniform walking past the real reunions, the ones that mattered. The ones with beginnings and middles and ends, like proper stories.He paused at the edge of the pier where the cement met the first stretch of actual land. People were hugging, crying, lifting toddlers in the air. One woman clung to her husband like she was afraid he'd disappear again if she loosened her grip. A little girl wore a t-shirt that said "Half my heart has been in the Persian Gulf." He watched it like TV, like something happening to other people in other lives.The Hopeful Voice: He smiled at that. That's the stuff you remember. That's the good part. Not the long watches or the midrats in the galley or the endless briefings. But this—people finding each other again. He smiled because it meant something was still working right in the world. And because next time, maybe there'd be someone waiting for him too. Maybe he'd call Rebecca when he got to a phone. They'd left things "on pause" before deployment, but maybe now...The Realist Voice: He didn't smile. Not really. What his face did was something else—a reflexive tightening of muscles that had nothing to do with joy. He adjusted his grip on the sea bag until the strap cut into his shoulder, a discomfort to focus on. It was all fine. No one owed him anything. He'd volunteered, after all. Signed the papers. Taken the oath. He repeated that to himself until he believed it for a full three seconds.A yellow cab pulled up at the pickup point, and he raised a hand. The driver didn't even get out to help with the bag. Just popped the trunk with a lever and waited, meter already running.Cab RideThe cab smelled faintly of cigarettes and old coffee, upholstery worn thin by thousands of nameless passengers. The driver didn't say much, just checked the mirror once—taking in the uniform, the close-cropped hair, the sea bag—and pulled out from the curb, merging into the traffic crawling away from the piers."Airport?" the driver asked, voice thick with an accent Reese couldn't place."Yeah. Norfolk International.""Coming home or going away?""Both, I guess."The driver nodded like this made perfect sense and fell silent again.The world outside the window was impossibly green after months of desert colors and open ocean. Lawn sprinklers casting rainbows in suburbia. Minivans carrying soccer teams. Mailboxes shaped like lighthouses. A whole

The Elephant Island Chronicles PresentsDon Juan's Most Beautiful LoveBy Jules Barbey d'AurevillyTranslated by Gio MarronTranslation NoteThis translation of Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly's "Le plus bel amour de Don Juan" represents a collaborative effort between myself, Gio Marron, with assistance from AI language models including Claude, ChatGPT, and Perplexity.The translation process involved multiple iterations, with initial drafts produced through AI assistance, followed by substantial literary refinement to capture the nuanced tone, style, and period-appropriate language of Barbey d'Aurevilly's distinctive prose. As primary translator, I focused on preserving the original's ornate, decadent literary style while ensuring readability for contemporary English-speaking audiences.Special attention was given to maintaining the psychological complexity and subtle irony that characterize Barbey d'Aurevilly's work, particularly the supernatural elements that transform this tale from a conventional seduction narrative into something more metaphysical and profound.The translation aims to serve both general readers interested in 19th-century French literature and scholarly audiences familiar with the Decadent movement and the evolution of the Don Juan archetype in European literary tradition.Gio Marron May 2025Don Juan's Most Beautiful LoveBy Jules Barbey d'AurevillyIn this masterpiece of psychological insight and irony, Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly transforms the Don Juan legend into a tale of supernatural suggestion. When a aging seducer recounts his "most beautiful love" to a circle of aristocratic women, the revelation subverts all expectations—proving that the most powerful conquests happen in the realm of imagination rather than the bedchamber. A brilliant exploration of innocence, corruption, and the mystical dimensions of desire from one of 19th-century France's most provocative writers.IThe devil's finest delicacy is an innocence. (A.)So he still lives, that old scoundrel?"By God, indeed he lives! — and by God's decree, Madame," I added, checking myself, for I remembered she was devout, and from the parish of Sainte-Clotilde no less—the parish of dukes! "The king is dead! Long live the king!" they used to say under the old monarchy before it shattered like Sèvres porcelain. Don Juan, democracy be damned, remains a monarch who will never be broken."Indeed, the devil is immortal!" she remarked, as if confirming something to herself."He has even—""Who? The devil?""No, Don Juan... supped, three days ago, in high spirits. Guess where?""At your dreadful Maison-d'Or, no doubt.""Fie, Madame! Don Juan no longer goes there... nothing there to fricassee for his grandeur. Lord Don Juan has always been somewhat like that famous monk of Arnaud de Brescia who, according to the Chronicles, lived solely on the blood of souls. That's what he likes to tint his champagne with—and such fare hasn't been found in courtesans' cabarets for quite some time!""I suppose," she resumed with irony, "he must have supped at the Benedictine convent with those ladies...""Of Perpetual Adoration, yes, Madame! For the adoration that devil of a man once inspired seems to me to last in perpetuity.""For a Catholic, I find you rather profane," she said slowly, though visibly tense, "and I ask you to spare me the details of your harlots' suppers, if speaking of Don Juan tonight is merely your invented way of reporting on their activities.""I'm inventing nothing, Madame. The harlots of the supper in question, if harlots they are, aren't mine... regrettably...""Enough, Monsieur!""Allow me to be modest. They were—""The mille e tre?" she asked, curiosity rekindling her almost-amicable manner."Oh! not all of them, Madame... Only a dozen. That's already quite respectable...""And disreputable too," she added."Besides, you know as well as I that not many can fit into Countess de Chiffrevas's boudoir. Grand things may have transpired there, but the boudoir itself is decidedly small...""What?" she exclaimed, surprised. "So it was in the boudoir that they supped?""Yes, Madame, in the boudoir. And why not? Men dine on battlefields. They wanted to give an extraordinary supper to Lord Don Juan, and it was worthier of him to offer it in the theater of his glory, where memories bloom in place of orange trees. A lovely notion, tender and melancholic! It wasn't the victims' ball; it was their supper.""And Don Juan?" she asked, as Orgon says "And Tartuffe?" in the play."Don Juan received the affair splendidly and supped magnificently,He, alone, before them all!in the person of someone you know... none other than Count Jules-Amédée-Hector de Ravila de Ravilès.""Him! He is indeed Don Juan," she said.And, though she had outgrown the age of reverie, this sharp-beaked, sharp-clawed devotee began to dream of Count Jules-Amédée-Hector—of that man of the Juan bloodline—that ancient, eternal Juan lineage, to whom God has not given the world, but has permitted the devil to bestow it upon him.IIWhat I had just told the old lady was the unvarnished truth. Barely three days had passed since a dozen women of the virtuous Faubourg Saint-Germain (rest assured, I shall not name them!) who, all twelve, according to the dowagers' gossip, had been on the most intimate terms (a charming old expression) with Count Ravila de Ravilès, had conceived the singular idea of offering him supper—with him as the only man—to celebrate... what? They didn't say. Such a supper was bold, but women, cowardly individually, are audacious in groups. Perhaps not one of this feminine banquet would have dared to offer it at her home, tête-à-tête, to Count Jules-Amédée-Hector; but together, bolstering one another, they had not feared to form the chain of Mesmer's tub around this magnetic and compromising man, Count de Ravila de Ravilès..."What a name!""A providential name, Madame... Count de Ravila de Ravilès, who, incidentally, had always obeyed the imperatives of this commanding name, was indeed the incarnation of all seducers spoken of in novels and history. Even the Marquise Guy de Ruy—that discontented old woman with cold, sharp blue eyes, though less cold than her heart and less sharp than her wit—herself admitted that in these times, when the woman question daily loses importance, if anyone could recall Don Juan, surely it was he! Unfortunately, it was Don Juan in the fifth act. Prince de Ligne could never comprehend how Alcibiades might reach fifty. Yet in this respect too, Count de Ravila would forever remain Alcibiades. Like d'Orsay, that dandy carved from Michelangelo's bronze who remained handsome until his final hour, Ravila possessed that beauty peculiar to the Juan race—that mysterious lineage which proceeds not from father to son like others, but which appears sporadically, at certain intervals, among humanity's families.It was true beauty—insolent, joyful, imperial, Juanesque beauty; the word says everything and dispenses with description. And—had he made a pact with the devil?—he retained it still... Only, God was exacting his due; life's tiger claws were beginning to score his divine brow, crowned with the roses of so many lips, and on his broad impious temples appeared the first white hairs announcing the approaching barbarian invasion and the Empire's end... He wore these, moreover, with the impassivity of pride intensified by power; but the women who had loved him sometimes regarded them with melancholy. Who knows? Perhaps they were reading the hour striking for themselves upon that brow. Alas, for them as for him, it was the hour of that terrible supper with the cold Commander of white marble, after which comes only hell—the hell of old age, until the real one arrives! And that is perhaps why, before sharing this bitter and final supper with him, they thought to offer him theirs, crafting it into a masterpiece.Yes, a masterpiece of taste, delicacy, patrician luxury, refinement, and exquisite conception; the most charming, delicious, dainty, intoxicating, and above all most original of suppers. Original! Consider—usually joy and the thirst for amusement inspire a supper; but here, it was memory, regret, almost despair—though despair in evening dress, concealed beneath smiles or laughter, still craving this final feast or folly, this last escapade toward youth returned for an hour, this final intoxication before bidding it farewell forever!The Amphitryonesses of this incredible supper, so incongruous with the trembling customs of their society, must have experienced something akin to Sardanapalus on his pyre, when he heaped upon it his women, slaves, horses, jewels—all his life's opulence to perish with him. They too heaped at this burning supper all their own opulence, bringing everything they possessed of beauty, wit, resources, adornment, and power, to pour it all, at once, into this supreme conflagration.The man before whom they draped themselves in this final flame meant more to their eyes than all Asia did to Sardanapalus. They were coquettish for him as no women had ever been for any man—let alone for one seated among twelve—and this coquetry they inflamed with that jealousy normally hidden in society, yet which they needn't conceal, for they all knew this man had belonged to each of them, and shame shared is shame dispelled... Among them all, each competed to engrave her epitaph deepest in his heart.He, that night, savored the satiated, sovereign, nonchalant, connoisseur's voluptuousness of both the nuns' confessor and the sultan. Seated like a king—like the master—at the table's center, facing Countess de Chiffrevas, in that boudoir the hue of peach blossom—or perhaps of sin itself (the spelling of that boudoir's color was never quite settled), Count de Ravila embraced with his hell-blue eyes, which so many poor creatures had mistaken for heaven's blue, that radiant circle of twelve women, dressed with genius, who at that table laden with crystal, lit candles, and flowers, displayed all the n

The Dancerby Rosauro AlmarioTranslated from the Tagalog (1910 Edition) by Gio Marron with AI assistance from ChatGPT, Claude, and PerplexityNarration by Eleven LabsForewordThe Dancer (Ang Mánanayaw) by Rosauro Almario, first published in 1910 by Aklatang Bayan in Manila, is a short Tagalog novel that serves as both a literary work and a moral allegory. Written during the early American colonial period in the Philippines, it stands as a window into a society undergoing cultural, political, and moral upheaval. This translation seeks to preserve not just the story, but the rhetorical force, social commentary, and emotional tone of the original.The novel follows Sawî, a provincial youth newly arrived in the city, and his fateful entanglement with Pati, a beautiful but cunning dancer in Manila. Their story is more than a tale of seduction and downfall; it is an exploration of urban corruption, class vulnerability, and the slow erosion of character under the pressure of illusion, lust, and modernity.Almario writes with didactic urgency. The prose is steeped in the influence of Spanish literary traditions, evident in its rhetorical flourishes and formal tone, but it also draws from native Tagalog moral storytelling. This dual heritage reflects the transitional identity of early 20th-century Filipino literature, which sought to both entertain and instruct in a time of national redefinition.The Dancer is not subtle. It is polemical, almost theatrical in its structure and tone, designed to shock, warn, and moralize. But in its theatricality lies its power. The dance halls of Manila become battlegrounds of virtue and vice. Pati, though framed as a femme fatale, is in fact a product of social decay—a survivor using what tools she has in a world that offers her few options. Sawî, for his part, is not simply a victim of seduction but of his own romantic delusions and failure to discern appearances from substance.This translation uses modern English dialogue conventions and idioms while preserving the formal diction and tonal gravity of the original. Where the Tagalog text relies on repetition or florid metaphor, the English renders those ideas with clarity but does not omit them. The goal is not modernization but accessibility—to bring Almario's moral vision and artistic voice to readers unfamiliar with early Tagalog prose.In its time, Ang Mánanayaw was part of a larger project by Aklatang Bayan: to use literature as a weapon in the fight against moral decline, colonial disorientation, and cultural amnesia. Today, it stands as a potent reminder of the tensions that defined Filipino identity in the shadow of empire, and the enduring battle between desire and dignity.Gio MarronThe DancerJóvenes qué estais bailando, al infierno vais saltando.[^1]Chapter One: BeginningPati: A dancer. Of indeterminate stature; neither short nor tall; her body robust, full of vitality, radiantly fresh; her large bluish eyes like twin windows from which a burning soul gazed out, a soul ablaze with the flames of passion flowing with momentary pleasures—pleasures that could drown, irritate, and ultimately destroy any soul foolish enough to immerse itself in them.Sawî[^2]: Born in the provinces, a young man pursuing his studies in Manila. Coming from a good family of means, Sawî was raised amidst plenty and comfort: timid, exceedingly shy, with somewhat delicate mannerisms, entirely unlike those city youths whose sole aspiration was to flit about like butterflies or bees, forever seeking new flowers from which to draw fragrance.Tamád[^3]: A wastrel, a good-for-nothing, as the common folk called him. Orphaned of both father and mother. Without wife, child, sibling, or any relation except for one: "Joy"—a joy that, for him, could never be found in any place or corner save for billiard halls, cockpits, gambling dens, dance houses, and those ever-hungry jaws of hell that always stood ready to receive him."Tamád, how's the bird?" Pati inquired."Good news, Pati—he's becoming quite tame now," Tamád replied."Ready to enter the cage, then?""Oh, without a doubt he'll enter it willingly!""What has he said to you about me?" she probed further.Tamád flashed a mischievous smile. "The same as when I first introduced you at that party. He declares you're beautiful as Venus herself, radiant as the Morning Star. He's already fallen for you! You can be certain he's ensnared in your net."Pati parted her crimson lips to release a resonant laugh."So he's in love with me already, is he?""And he'll be searching for you later tonight.""Where? Where did you tell him I would be?""At the dance hall.""Then he already knows I'm a dancer?" she asked with feigned concern. "And what was his reaction? Hasn't he read those newspaper reports claiming that women who dance at subscription parties aren't women at all but merely a bundle of leeches in skirts?""He... he mentioned something of that nature," Tamád acknowledged. "But I assured him such rumors might occasionally hold truth, but not invariably. 'Pati,' I told him, 'that young woman I introduced at the party is living proof that a beautiful pearl may yet be found amidst the mud...'"Tamád paused momentarily to swallow before continuing:"And Sawî—our bird in question—believed me entirely. He's convinced you're a 'rare pearl,' a modest young woman of virtue and dignity.""And didn't he question why I found myself in a dance hall?" Pati asked."He did ask—how could he not?" replied Tamád. "But the tongue of Tamád—your faithful procurer—created such elaborate dreams in that moment, painting images so lifelike they appeared as truth itself, witnessed by my own eyes. I told him, my voice nearly breaking with emotion: 'Oh, Sawî, if you only knew the complete history of Pati—the beautiful Pati whom you so admire—you would surely see her in your mind's eye as nothing less than a virtuous woman, a paragon of maidenhood. For she,' I continued dramatically, 'is an orphan who has endured considerable misfortune in life, reduced to begging, to pleading for alms, and when those she approached no longer extended their compassion, she was forced into servitude, selling her strength to a wealthy man... but...'""What happened next in this fabrication of yours?" Pati asked with an arched eyebrow."The wealthy man," Tamád continued with theatrical flair, "confronted with your unrivaled beauty, developed designs to violate your honor.""Violate!" Pati scoffed. "You've quite a talent for weaving falsehoods. And what heroic action did I supposedly take?""You resisted his base desires with unwavering virtue.""And then?""You departed from the house where you served to enter—by necessity—the profession of dancing.""So in summary," Pati concluded with sardonic precision, "in Sawî's imagination, I am a virtuous woman, an orphan mistreated by Fate, who became a beggar, then a supplicant, a servant, essentially a slave; and because I defended my honor, I left the wealthy man's house to enter a different profession. Is that the fiction you've constructed?""Precisely so," Tamád affirmed with satisfaction.Oh, if only God had ordained that lies, before leaving the lips of liars, should first transform into flames...!Pati, to those of us who truly knew her, was nothing but a baitfish[^4]—outwardly displaying only the glittering shimmer of scales while harboring nothing but fetid mud within. She was not merely flirtatious or fickle; she was something far more dangerous—a predator, an executioner of souls unfortunate enough to fall into her embrace.Even as a young girl—barely blossoming into womanhood—Pati had already inspired fear among the young men in her neighborhood. How could they not be wary when she would consent to anyone's advances, make promises to everyone, swear oaths to all comers? Each promise and oath was sealed with some token or pledge extracted from her victims—deposits that could never be reclaimed once given.But now Tamád was speaking again. Let us listen to his words:"Pati," he said with a smirk, "later tonight I shall certainly bring your bird to you.""When you arrive," she replied coolly, "the cage will be ready and waiting."And with that exchange, they parted ways.Chapter Two: The Cage OpensThey had already arrived at the first step of the stairway that led into Pluto's realm[^5]: the dance hall. Tamád led the way, the tempter, while Sawî followed timidly behind him.The Temple of the cheerful goddess Terpsichore[^6], at that moment, transformed into a veritable Garden of Delights: everywhere the eye turned, it beheld nothing but modern-day Eves and latter-day Adams. Throughout this Eden, flowers seemed to have scattered themselves of their own accord, while human butterflies flitted to and fro, dancing around one another in perpetual motion.Upon the arrival of Sawî and Tamád at the dance hall, Pati, who had been waiting for them, cheerfully came forward and, with a smile and a laugh, greeted them:"You've wandered in here..."Sawî did not respond. Pati's words, those utterances that seemed as if dipped in sweetness, reached one by one into the heart of the stunned young man. How beautiful Pati looked at that moment!Inside her dress that shimmered with light, in Sawî's vision she resembled what Flammarion saw in his dream: a person made of light, and her hands were two wings.Tamád, seeing his companion freeze like this, winked once at Pati and secretly pointed to him: "He's truly awkward!"Just then, a signal from the orchestra was heard:"Waltz!" called out the impatient dancers in unison.And the large hall echoed with the scuffing of shoes.Pati, who had moved away from the two companions, at the beginning of the dance approached Sawî again:"Would you like to dance?" she asked affectionately."No... it's up to you... perhaps later." And he stood up as if warmed by sitting too long; he took a handkerchief from his pocket and wiped the sweat that was beading on his forehead."Too shy for your own good!" murmured the beautiful dancer. And she turned her b

The Elephant Island ChroniclesPresentsThe CastawayRabindranath TagoreNarration by Eleven LabsForewordIn The Castaway, Rabindranath Tagore harnesses the quiet violence of human longing and the moral ambiguities of kindness to deliver one of his most psychologically intricate and emotionally potent stories. Set against the monsoon-churned banks of the Ganges, the story begins with a literal storm—yet the real turbulence brews within a household, beneath the surface of affection, class, duty, and misunderstanding.Tagore presents Nilkanta not as a simple waif but as a symbol of the precarious outsider—the emotionally rich but socially disposable figure whose very presence unsettles the structures of domestic comfort. Through him, the author interrogates how quickly charity can curdle into suspicion, and how affection, unmoored from comprehension, can drift into tragedy. That Nilkanta is both a source of joy and a catalyst for quiet ruin is no accident. Tagore writes him with a tenderness that never slips into sentimentality and with a critique that never hardens into cruelty.Kiran, the woman whose sympathy becomes the fulcrum of the boy’s fate, is not simply a “nurturing presence.” She is something more complex: a person capable of both great warmth and great blindness. Her kindness is instinctive, but it is not always just. Her protectiveness, though sincere, lacks understanding of the deeper conflicts swelling within the boy she has unwittingly mothered, idealized, and misread.Tagore understood well the quiet wars of the heart—the ways in which loneliness, adolescence, jealousy, and misplaced love can twist a moment of impulse into a life-shaping event. What makes The Castaway endure is its refusal to resolve that tension. Nilkanta is not vindicated, nor is he condemned. He disappears, leaving behind not a lesson but a wound—one that reminds us of how easily love can misfire when wielded without full attention to the soul it tries to save.Written with restraint and irony, The Castaway remains one of Tagore’s most haunting pieces. It resists closure, denies the reader a villain, and instead invites us to consider our own roles in the lives of those we claim to care for. In doing so, it speaks not only to the social mores of colonial Bengal, but to timeless truths about the costs of misunderstanding and the limits of even the most well-meaning compassion.Gio MarronThe Castawayby Rabindranath TagoreTowards evening the storm was at its height. From the terrific downpour of rain, the crash of thunder, and the repeated flashes of lightning, you might think that a battle of the gods and demons was raging in the skies. Black clouds waved like the Flags of Doom. The Ganges was lashed into a fury, and the trees of the gardens on either bank swayed from side to side with sighs and groans.In a closed room of one of the riverside houses at Chandernagore, a husband and his wife were seated on a bed spread on the floor, intently discussing. An earthen lamp burned beside them.The husband, Sharat, was saying: "I wish you would stay on a few days more; you would then be able to return home quite strong again."The wife, Kiran, was saying: "I have quite recovered already. It will not, cannot possibly, do me any harm to go home now."Every married person will at once understand that the conversation was not quite so brief as I have reported it. The matter was not difficult, but the arguments for and against did not advance it towards a solution. Like a rudderless boat, the discussion kept turning round and round the same point; and at last threatened to be overwhelmed in a flood of tears.Sharat said: "The doctor thinks you should stop here a few days longer."Kiran replied: "Your doctor knows everything!""Well," said Sharat, "you know that just now all sorts of illnesses are abroad. You would do well to stop here a month or two more.""And at this moment I suppose every one in this place is perfectly well!"What had happened was this: Kiran was a universal favourite with her family and neighbours, so that, when she fell seriously ill, they were all anxious. The village wiseacres thought it shameless for her husband to make so much fuss about a mere wife and even to suggest a change of air, and asked if Sharat supposed that no woman had ever been ill before, or whether he had found out that the folk of the place to which he meant to take her were immortal. Did he imagine that the writ of Fate did not run there? But Sharat and his mother turned a deaf ear to them, thinking that the little life of their darling was of greater importance than the united wisdom of a village. People are wont to reason thus when danger threatens their loved ones. So Sharat went to Chandernagore, and Kiran recovered, though she was still very weak. There was a pinched look on her face which filled the beholder with pity, and made his heart tremble, as he thought how narrowly she had escaped death.Kiran was fond of society and amusement; the loneliness of her riverside villa did not suit her at all. There was nothing to do, there were no interesting neighbours, and she hated to be busy all day with medicine and dieting. There was no fun in measuring doses and making fomentations. Such was the subject discussed in their closed room on this stormy evening.So long as Kiran deigned to argue, there was a chance of a fair fight. When she ceased to reply, and with a toss of her head disconsolately looked the other way, the poor man was disarmed. He was on the point of surrendering unconditionally when a servant shouted a message through the shut door.Sharat got up and on opening the door learnt that a boat had been upset in the storm, and that one of the occupants, a young Brahmin boy, had succeeded in swimming ashore at their garden.Kiran was at once her own sweet self and set to work to get out some dry clothes for the boy. She then warmed a cup of milk and invited him to her room.The boy had long curly hair, big expressive eyes, and no sign yet of hair on the face. Kiran, after getting him to drink some milk asked him all about himself.He told her that his name was Nilkanta, and that he belonged to a theatrical troupe. They were coming to play in a neighbouring villa when the boat had suddenly foundered in the storm. He had no idea what had become of his companions. He was a good swimmer and had just managed to reach the shore.The boy stayed with them. His narrow escape from a terrible death made Kiran take a warm interest in him. Sharat thought the boy's appearance at this moment rather a good thing, as his wife would now have something to amuse her, and might be persuaded to stay on for some time longer. Her mother-in-law, too, was pleased at the prospect of profiting their Brahmin guest by her kindness. And Nilkanta himself was delighted at his double escape from his master and from the other world, as well as at finding a home in this wealthy family.But in a short while Sharat and his mother changed their opinion, and longed for his departure. The boy found a secret pleasure in smoking Sharat's hookahs; he would calmly go off in pouring rain with Sharat's best silk umbrella for a stroll through the village, and make friends with all whom he met. Moreover, he had got hold of a mongrel village dog which he petted so recklessly that it came indoors with muddy paws, and left tokens of its visit on Sharat's spotless bed. Then he gathered about him a devoted band of boys of all sorts and sizes, and the result was that not a solitary mango in the neighbourhood had a chance of ripening that season.There is no doubt that Kiran had a hand in spoiling the boy. Sharat often warned her about it, but she would not listen to him. She made a dandy of him with Sharat's cast-off clothes, and gave him new ones also. And because she felt drawn towards him, and had a curiosity to know more about him, she was constantly calling him to her own room. After her bath and midday meal Kiran would be seated on the bedstead with her betel-leaf box by her side; and while her maid combed and dried her hair, Nilkanta would stand in front and recite pieces out of his repertory with appropriate gesture and song, his elf-locks waving wildly. Thus the long afternoon hours passed merrily away. Kiran would often try to persuade Sharat to sit with her as one of the audience, but Sharat, who had taken a cordial dislike to the boy, refused; nor could Nilkanta do his part half so well when Sharat was there. His mother would sometimes be lured by the hope of hearing sacred names in the recitation; but love of her mid-day sleep speedily overcame devotion, and she lay lapped in dreams.The boy often got his ears boxed and pulled by Sharat, but as this was nothing to what he had been used to as a member of the troupe, he did not mind it in the least. In his short experience of the world he had come to the conclusion that, as the earth consisted of land and water, so human life was made up of eatings and beatings, and that the beatings largely predominated.It was hard to tell Nilkanta's age. If it was about fourteen or fifteen, then his face was too old for his years; if seventeen or eighteen, then it was too young. He was either a man too early or a boy too late. The fact was that, joining the theatrical band when very young, he had played the parts of Radhika, Damayanti, and Sita, and a thoughtful Providence so arranged things that he grew to the exact stature that his manager required, and then growth ceased.Since every one saw how small Nilkanta was, and he himself felt small, he did not receive due respect for his years. Causes, natural and artificial, combined to make him sometimes seem immature for seventeen years, and at other times a mere lad of fourteen but far too knowing even for seventeen. And as no sign of hair appeared on his face, the confusion became greater. Either because he smoked or because he used language beyond his years, his lips puckered into lines that showed him to be old and hard;

The Elephant Island ChroniclesPresentsTwo Pair of TruantsBy Beach and Bog-Land Some Irish StoriesBy Jane BarlowForeword by Gio MarronForewordIn an age of national revival and literary gravitas, Jane Barlow stood apart—not by rejecting Ireland’s rural life, but by portraying it with clarity, affection, and mischief. “Two Pair of Truants”, nestled within her 1905 collection By Beach and Bog-Land, is one of her most deftly balanced pieces: humorous without malice, provincial without condescension, and vividly local without descending into caricature.Barlow was among the few late-Victorian Irish writers to center her fiction on the domestic and social rhythms of the countryside without the scaffolding of myth or melodrama. Rather than depicting Ireland as a political chessboard or romantic ruin, she offered it as a living, breathing, wonderfully muddled place—where children skip school, mothers fret, policemen misidentify toddlers, and donkeys refuse to cooperate.In “Two Pair of Truants,” we follow two overlapping misadventures: one by Minnie and Baby Lawlor, little girls who seize an accidental holiday to chase glimpses of aristocratic grandeur; the other by Mick and Rosanna Tierney, would-be fairgoers who ditch their siblings at a police barracks to enjoy the pleasures of Killavin Fair unburdened. The ensuing chaos—of lost children, mistaken identities, and a community’s hilariously misplaced reactions—becomes a canvas for Barlow’s quiet satire.What gives the story its enduring charm is not just the plot, but the way Barlow inhabits her world. Her ear for Hiberno-English is pitch-perfect, her eye for social foibles sharp, and her tone unsentimental yet humane. The children here are not angels nor moral lessons in motion; they are mischievous, imaginative, and gloriously flawed. The adults, for their part, are equal parts worried, clueless, and stubborn. Authority figures fumble, assumptions pile up, and what should be a crisis dissolves into a comedy of errors.Behind the humor, however, is a subtle commentary on adult hypocrisy and the blurry lines between order and disorder in small communities. Barlow doesn’t scold; she observes. And what she observes is both timeless and particular: the petty tyrannies of domestic life, the fleeting thrills of forbidden adventure, and the constant tension between propriety and freedom.“Two Pair of Truants” deserves renewed attention not just as a charming children's caper, but as a finely constructed piece of realist storytelling that gently mocks the structures of rural life while celebrating its characters’ irrepressible vitality. Jane Barlow’s fiction, long overshadowed by her more canonical contemporaries, rewards us with an Ireland not torn by rebellion or framed in Celtic mist—but by laughter, misunderstanding, and the ever-complicated art of getting children to school on time.By Beach and Bog-Land: Some Irish Stories“Two Pair of Truants”by Jane BarlowEver since little Minnie Lawlor, accompanied by her mother and younger sister, had come to live with her grandmother in a gate-lodge of Shanlough Castle, her great wish had been to visit the castle itself, which was always whetting her curiosity by showing just the rim of one turret, like the edge of a crinkled cloud, over the rounded tree-tops in the distance. But it was not until some months had passed that she found an opportunity. Then, on a showery May morning, her mother set off early to Killavin Fair; her grandmother was pinned to the big chair in the chimney-corner by an access of rheumatics; Lizzie Hackett, the cross girl who scrubbed for them, sent word that she could not come till noon; and, as the last link in this chain of lucky chances, the rope-reins of Willie Downing’s ass-cart snapped right in front of the lodge gate just when Minnie and Baby were setting off for school. “Bad manners to you, Juggy, for a contrary ould baste!” Willie was saying as he halted for repairs. “Would nothin’ else suit you but to set me chuckin’ th’ ould reins till they broke on us in a place where a man hasn’t so much as a bit of string?” Willie, being twelve years old, seemed of formidable age and size to Minnie, who was seven: but the good-natured expression of his face, where large freckles made a well-covered pattern, emboldened her to propose the plan which had occurred to her at the sight of the empty ass-cart. As a preliminary, however, she supplied him with the longest bit of twine she could twitch from the thrifty wisp hung on the hook of a dresser. After which, “Is it anywheres near the castle you’ll be drivin’ to?” she inquired, pointing in that direction.“I’m apt to be passin’ it pretty middlin’ near,” said Willie, struggling to knot a pair of rather skimpy ends.“And do you think you could be takin’ me and Baby along wid you that far?” said Minnie.“What for at all?” he said, looking doubtful.“To see the grandeur that’s in it,” replied Minnie.“Up at th’ ould place?” said Willie. “I never heard tell there was any such a thing in it.”“Well, there’s grand people in it, at all events,” said Minnie. “Me grandmother does be sayin’ the Fitzallens hasn’t their equals next or nigh them. Lords of the land they are, and the top of everythin’. I’d like finely to be seein’ them, and so would Baby. But if we’ve any talk of walkin’ a step up the avenue, me grandmother always says: ‘On no account suffer them, Maria; it mightn’t be liked by the Family.’ So we do be stoppin’ in the little ugly shrubbery.”“I dunno is there e’er a lord in it,” said Willie, doubtfully. “If there is, I never laid eyes on him.” This was disappointing.“I suppose you’re very ignorant,” Minnie remarked after a slight pause, as if she had sought and found a satisfactory explanation.“Pretty middlin’ I am, sure enough,” Willie said more decidedly, and then added, as if he, too, had hit upon a probable conjecture: “Belike yous would be wantin’ to see Mrs O’Rourke, th’ ould housekeeper?” Minnie might have replied truly that she had never heard tell of any such person; but as the idea seemed to remove her new acquaintance’s difficulties she answered: “Ay, sure we could go see her if you took us along. I can step in meself over the wheel, and you can aisy give Baby a heft up.” “But in my belief it’s goin’ to school the two of yous had a right to be,” Willie said, relapsing into doubt again as he glanced at their small bundle of ragged-edged books.“Och, me mother’d say we might have a holiday this minyit, only she’s went to the fair,” Minnie affirmed confidently, though she might have had some difficulty in reconciling this belief with her gladness that there was not present anybody whose permission need be asked. “I’ll get in first.”“Themselves inside there might be infuriated wid the whole of us,” said Willie, still unconvinced.“Sure you’re not a tinker, are you?” Minnie said, ostentatiously surveying the no-contents of the cart. “They do be biddin’ us have nothin’ to say to tinkers, but ne’er a tin can or anythin’ I see in it.” As Willie’s objections seemed to be over-ruled by this argument, she continued: “So Baby and I’ll run in and leave our books, and get our good hats; we’ll be back agin you have the reins mended—mind you wait for us.”Her anxiety about her appearance before the eyes of the grand people made her risk losing the chance of seeing them at all as she hurried herself and her sister into their best jackets and new hats trimmed with pink gauze and daisies; while a wild hope she secretly entertained that they would be offered hospitality up at the castle led her to discard the basket containing their dinners. Baby, indeed, was inclined to demur at this, so Minnie compromised the matter by extracting the two oranges which crowned the menu, and Baby, bearing the golden balls, followed as contented as any ordinary queen.The ass-cart had obligingly waited for them, and Willie Downing had spread a sack for them to sit on at the back. He also helped Baby to scramble up, but unfortunately said to Minnie, “You’d better be keepin’ a hold on her, for ones of that size don’t have much wit. She’d drop off as aisy as a sod of peat, and be delayin’ me to pick her up”—a remark which Baby resented, as albeit three years short of Minnie’s age, and thrice as young as Willie, she had a strong sense of her own dignity. Otherwise the drive was very thoroughly enjoyable. The cart was not, indeed, a luxurious vehicle, being simply a flat wooden tray on wheels, with no springs to soften its jolts, and no rail to prevent one of them from jerking out an unwary passenger. But the little girls thought it a most desirable substitute for their stuffily stupid schoolroom, and when they were rocked as if in a boat on a choppy sea, Minnie said that it was as good as going two ways at once. Juggy’s pace was slow, as suited her venerable appearance, for many years had made her as white as if she had been bleached and as stiff as if she had been starched. Willie had a thick ash stick, with which he every now and then made a loud rattling clatter on the front board of the cart. “You might as well,” he explained, “be batin’ ould carpets as Juggy, but the noise keeps her awake sometimes.” Minnie and Baby, however, had so much to look at in the strange bog-land through which the cart was passing that they were in no hurry for the end of their drive. In fact, even Minnie felt a little forlorn when Willie drew up at a small gate in a high stone wall and said: “I’ll be droppin’ yous here. It’s the nearest I can be bringin’ yous to the castle. You’ll find your ways to it pretty middlin’ aisy by them shrubbery paths, unless you take the wrong turn; you might ready enough, for there’s a dale of diff’rint walks through it, but they’ll bring you somewheres anyhow. Git along out of that, Juggy.” For then it suddenly occurred to her that they had come a long way, which they must travel back all by themselves. Willie’s directions, too, were not by any means as clear as she could have wished, but no more