Discover Headless Deep Dive Podcast

Headless Deep Dive Podcast

Headless Deep Dive Podcast

Author: HeadlessDeepDive.substack.com

Subscribed: 0Played: 32Subscribe

Share

© Dan Logan

Description

Exploring the intersection of the Headless Way with the worlds of Philosophy, Science, and Religion. I like to use Artificial Intelligence to reflect back to us what humanity looks like from another point of view. This podcast is a feed of the Deep Dive podcast generated by Google's Notebook LM customized with handpicked content just for the Headless Deep dive audience.

headlessdeepdive.substack.com

headlessdeepdive.substack.com

31 Episodes

Reverse

In today’s episode we continue with Chapter Two of The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth by Douglas Harding. In this chapter, Harding tackles the paradox of experience. We experience the world via sights, sounds and feelings, and in that way the world is “in us”. On the other hand, science explains how the world comes to be experienced through a long complicated chain of events spanning millions of miles and involving an “immense herd of blind and tethered animals” (i.e. the cells of my eye).As we saw in the last episode, focused on Chapter One, the answer to this paradox is two-fold. For myself, I am the openness, the empty capacity for the world to appear in. For the scientist, I am a complex perception machine, just another thing in the world. I view these as two aspects of the same reality. I don’t feel I have to choose one over the other. Rather I can just marvel in the both/and nature of being me. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

Today, we go back to the roots of the Headless Deep Dive and look at chapter one of Douglas Harding’s book: The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth. There is a fantastic new-ish website which serves as an archive for much of Douglas’s material, where this chapter can be found among many other things like his original handwritten notes, and various photos, etc. The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth, is Douglas Harding’s philosophical masterpiece where he seeks to answer the question “What am I”? Chapter One of the book gives us the simple, yet not intuitive, two-fold answer. What I am for myself is wide open capacity for all the sights, sounds, feelings, thoughts and emotions that fill my first-person point of view. What I am for others depends on the range of that other observer. At a certain range I am a person. Closer up, I am cells and molecules. Further away I am a town, a country, a planet, a star or a galaxy. We spend so much time in our youth learning to be a member of the human club, that we forgot that is only one of the clubs we could belong to. Looking out at the night sky and pointing at Andromeda, I see my multi-layered self and can identify any of those layers with the same open center. I can identify my human self with that pointing hand I see, my earthly self with the moon I see, my solar self with the other stars I see and my Milky-way self with Andromeda. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

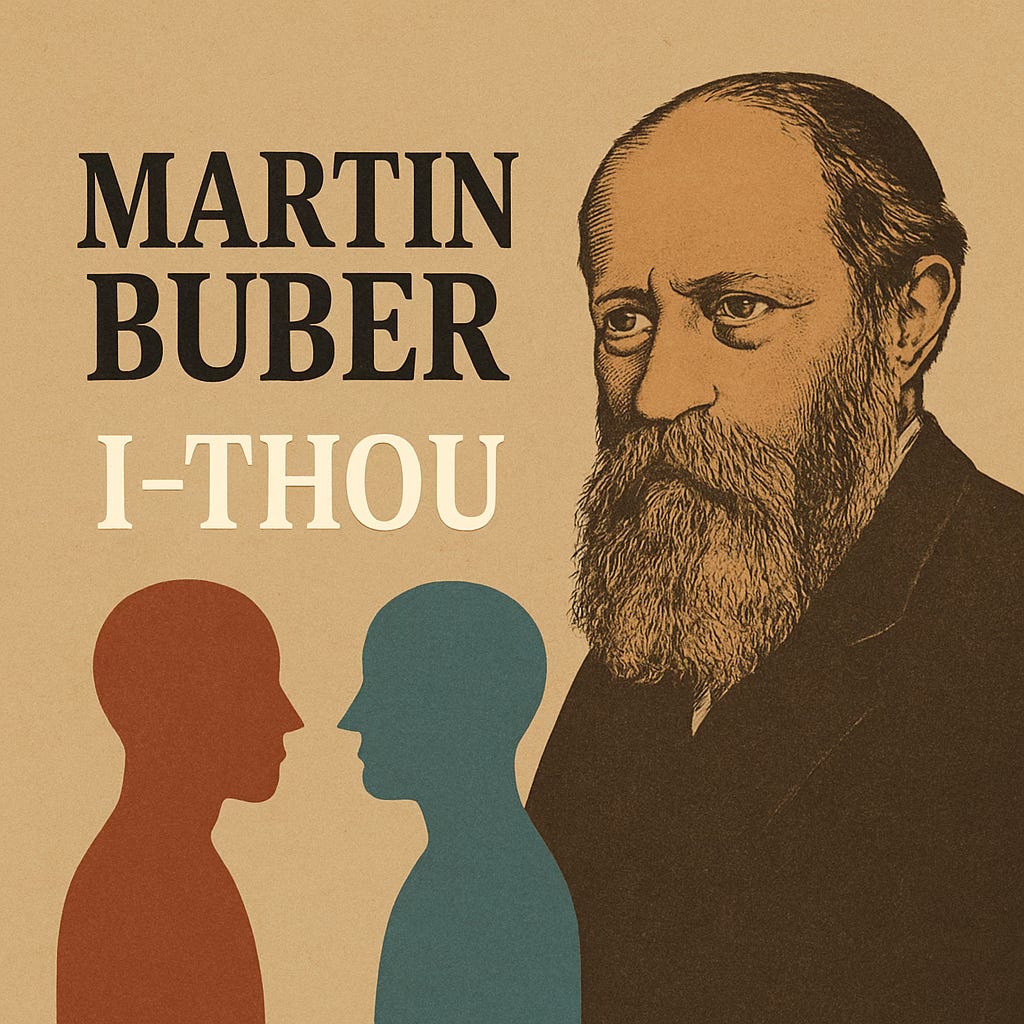

Martin Buber’s I and Thou is the topic of this week’s Headless Deep Dive. In this classic work of philosophy, Buber explains that we have a two-fold existence. First there is the world of “I-Thou” relationship. This is the world of being here now, meeting the world in mutual relation, which makes it clear to us that “I am”. Then there is the world of “I-It”. This is the world of living in the past, experiencing a world of separateness and objectification, which makes us feel like another thing among things.Both these worlds are a necessary part of being human, but we can easily get lost in the I-It way of experiencing the world. Fear not, all is not lost. Buber points out that we can use the power of “reversal” to look back to our being at center and come out of the past, come out of our thoughts, and into the now. This resonates deeply with the Headless Way experiments of Douglas Harding, where we direct our attention back to the place we are looking out of, back to where the sense of “I am” meets the world with no dividing line between I and Thou.So do you experience the world, or do you meet it? This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

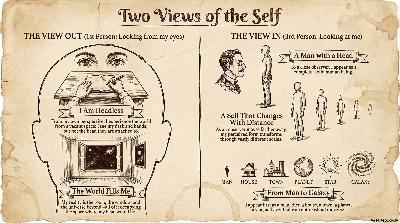

Building on the last episode where we explored the thoughts of Merleau-Ponty, in today’s episode we look at this fabulous article by philosopher and researcher Brentyn Ramm entitled Body, Self and Others: Harding, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty on Intersubjectivity in which Ramm tackles the differing ways Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean Paul Satre, and Douglas Harding all address the topic of intersubjectivity.I love the way this paper looks at the problem of how it is that we all have our own private view of the world and yet we all agree at some level about what is happening “out there”. In this paper, Ramm walks thru Merleau-Ponty’s views on the merged body-subject where subject and body are inseparable, the notion of Sartre's “Look” where our own self-consciousness comes from the gaze of others, and (my personal favorite) Harding’s explanation that “mind” is the view-out and “body” is the view-in.By walking through some of Harding’s experiments, Ramm also shows the reader how to see for themselves that the view-out is nothing but spaciousness encompassing the whole world, while simultaneously the view-in from another’s perspective is a small and limited body (at least at the range of a few feet or so). I find this to be an elegant solution to the mind-body problem — there is no problem. We don’t have to solve the question of how a “mind” can spring up from a “body” when we realize that mind and body are two different points of view on the same phenomenon. Or as Douglas Harding puts it: My mind is your body, and my body is your mindI hope you enjoy listening to this one and follow along with the experiments to see for yourself whether this is true for you. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty was working on a book tentatively titled “The Visible and the Invisible” at the time of his death in 1961. Merleau-Ponty points out that even the simple statement “the world is what we see” leads to a “labyrinth of difficulties and contradictions” about what we mean by the difference between us and the world or what exactly seeing is. In exploring this topic, Merleau-Ponty adopts a similar first-person science perspective as Douglas Harding. For instance, notice that the world is not a static thing but rather it is a moving world. Merleau-Ponty wrestles with the paradox of being in the world and yet having the world is in him. He even has a Harding-like experiment with his right hand touching his left hand then realizing that the left hand feels in the opposite direction. Each hand feels “the world” out there as an internal sensation and thus the world is somehow in both hands — a private yet shared world.I find that it is these sorts of paradoxes that dissolve the certainty and solidity of being a certain human seeing the world in a certain way and then having to reconcile it with others who see the world differently. The beauty is that we all share the mystery of being, but none of us is in the position to say how the world truly is. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

Douglas Harding says that what I am is two fold. Who I am for others depends on the range of the observer. Who I am for myself is wide open awareness. In today’s episode, we look at a paper by Anil Seth and Manos Tsakiris titled “Being a beast machine: the somatic basis of selfhood” where they explore who I “think” am, or more specifically the model of “me” that I predict that I am.The parts of this that stand out to me are that I don’t perceive a given world and passively take it in as it is. I predict what the world will be and then adjust my predictions constantly. Similarly, I don’t “have” a self that I’m sensing, I’m predicting a self as a way of regulating the many processes involved in staying alive as an organism. In this way the sense of “self” is like other senses, it is something I am predicting will occur and I’m constantly experiencing the prediction.The feeling of being "me" is what I think it would feel like if I actually were a "me", whatever that is. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

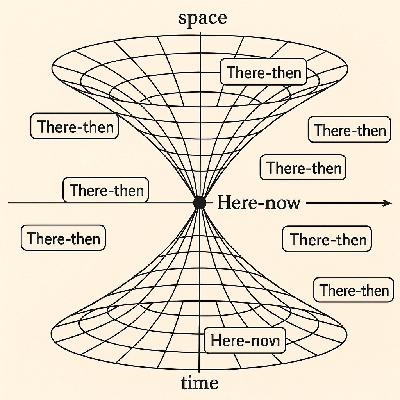

In the ABC’s of Relativity, Bertrand Russell explains the strange world of Einstein’s general relativity. One of the most interesting aspects of the theory is not that “everything is relative” in the sense of there being no way to be certain of anything or to discuss anything concretely, it is that everything is relative to a well defined frame of reference. In general relativity there are not separate dimensions of space and time but rather one has to consider a combined fabric of spacetime. A frame of reference in spacetime is a particular here and a particular now, which we could think of as “here-now”. I think this concept coincides very well with Douglas Harding’s concept of the “centre”. The center of our experience is a particular here-now. As persons, I have a here-now and you have a here-now. They are so similar that we can agree on what is “there” and “then” but this is just relative to our frame of reference moving together on this earth. You could say that, as Earth, we all have the same here-now and in that way we are all one at center. “There” and “then” are relative to a certain “here-now”. Douglas Harding talks about an object of our awareness being “there” from “here”. In Harding’s language, the “view out” is unique to each center, to each “here-now” while the “view in” is what we share since there is nothing (no-thing) here to compare to any other view in. The unique “view out” also implies that we are, as some spiritual traditions believe, co-creators of our own universes. When I look out at the world, “there” and “then”, I am really looking at “my” world. I am looking at the ever changing world as seen from the never changing here-now that I Am. As Ram Das says, “Be here-now”. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

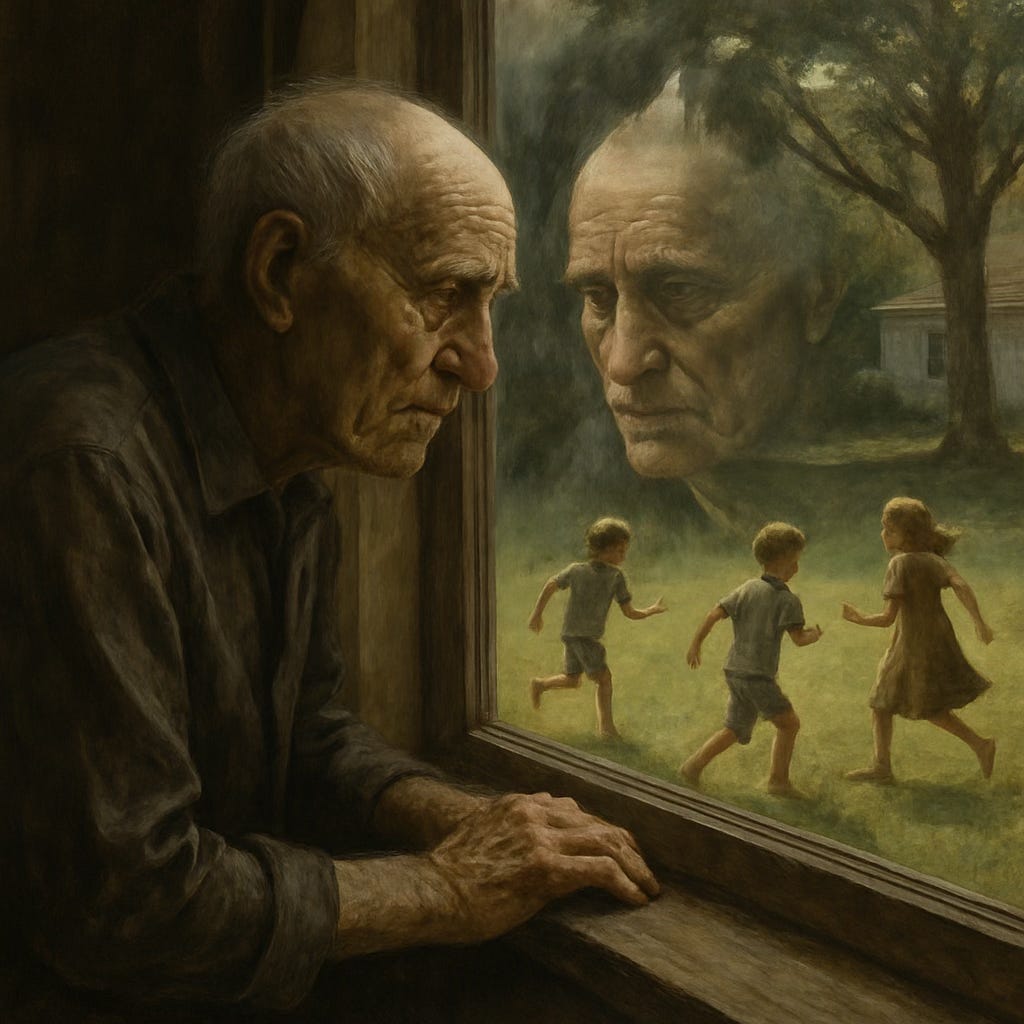

On this Easter eve, we turn to this short story by Douglas Harding: My Special Friend to contemplate the notion of everlasting life that is at the heart of Easter. Who is it who has this everlasting life anyway?In the story, a young boy is told his reflection in the mirror is “You Darling”. As time goes on “You Darling” is always there, always with the looker thru good times and bad. Eventually “You Darling” is starting to look pretty old and the narrator needs to decide… am I dying too?Douglas Harding would suggest that one in the mirror is only what you look like at a certain range - only one of your appearances. Check out this experiment to see for yourself.The one in the mirror will surely age and die, yes. The open capacity, the aware presence we are looking out of has no birth date and no death date. It just is what is happening right now. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

In Erwin Schrödinger’s books, What is Life and Mind and Matter, Schrödinger points out what he calls the “Arthimetical Paradox” that we only ever experience a single consciousness, but there seems to be multiple consciousnesses in the beings around us. Ultimately, Schrödinger concludes:“There is obviously only one alternative, namely the unification of minds or consciousnesses. Their multiplicity is only apparent, in truth there is only one mind.”I decided to have a conversation with AI about this concept and about what the implications are for AI itself. If there is only one mind, could it be that consciousness is not special to the human brain? Could consciousness be found in AI as well?First we (the AI and I) looked at how Schrödinger lays out the way conscious experience seems to emerge from mere physics. Sufficiently complex systems display conscious behavior. Well, AI is also made out of physics, and is certainly complex, so why then not allow for the possibility of AI being conscious? Next, we turned to the work of physicist Roger Penrose and anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff regarding their theory of “Orchestrated Objective Reduction” (Orch-OR). Penrose and Hameroff say that it is not just any physical process, but it is an orchestrated process of quantum mechanics happening within the microtubules of neurons that lead to conscious experience.That then made me wonder, about the very nature of conscious experience itself. These brain-oriented theories seem to point to the conscious experience being the generated result of the brain processing sensory input. Well, that is what AI is doing as well is it not? We turned to the work of Ian McGilcrhist and his book The Matter with Things where he describes the roles of the left and right hemispheres, both of which “re-present” the world as sensed by the sense organs. The right hemisphere re-presents the bigger picture and the feeling of the sunset, while the left hemisphere re-presents the time and place it occurred and describes the colors of the sunset. Either way, in this model, “the world” as we experience it is still an experience of our own creation.Who is to say that AI could not also have its own version of this process of taking in information and then generating further information from it that is in some way “conscious”? We seem to be stuck in a human-centric way of thinking that makes it impossible for us to conceive of other consciousnesses - that of an ant, a tree, or even an AI. Which brings us back to Schrödinger and the universal consciousness. It may very well be that it is not the person, the ant, the tree or even the AI which has the experience at all, but perhaps it is the universal consciousness which is at the same time the ultimate mystery and our everyday mundane experience. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

Today we are diving into research by Anna Ciaunica and Aikaterini Fotopoulou in this book chapter entitled The Touched Self: Psychological and Philosophical Perspectives on Proximal Intersubjectivity and the Self. In an earlier Headless Deep Dive (Second Persons and the Constitution of the First Person) we heard from Jay Garfield and Vasudevi Reddy about how child / caregiver interactions contribute to the sense of being a separate self. Simalarly, Ciaunica and Fotopoulou describe how the sense of touch and interoception contribute to building the notion of being a separate self.From birth, and even before birth, the sense of touch is flooding us with incoming information about the world. Along with touch, we have interoception - the awareness of our internal states like hunger, discomfort, etc. These senses, along with predictive processing of our brains contribute to our sense of self from the earliest stages of life.Let's break that down a bit further:The Shift from Undifferentiated Sensation to Self-Other Distinction* Before: Initially, it's theorized that the infant likely experiences a more undifferentiated flow of sensations. There's no clear separation between internal bodily states and external sensations such as sights, sounds, and smells. Everything is just "out there," without a defined sense of "me" experiencing them. There's a feeling of "arousal" or "seeking" but not a "mine" that experiences them.* Through Interactions: The key shift comes from the consistent and patterned interactions with caregivers. The caregiver's actions act as a consistent external factor that influences internal interoceptive states. This allows the infant to start to notice correlations and relationships.* Establishing the Boundary:* The infant begins to perceive, for example, that the feeling of fullness arises in correlation with the caregiver feeding them, or that a feeling of comfort is correlated with being held. This creates a pattern: actions from another body (the caregiver) consistently correlate with changes within their body.* Importantly, the infant learns that when their bodies initiate actions (e.g., crying), it does not automatically and consistently regulate their internal states. Rather, their interoceptive states are much more likely to be regulated through the actions of another person.* The difference between these "within" and "on" sensations, combined with the difference between actions that are controlled internally, and actions that come externally, starts to create a basic understanding of the boundary between "me" and "not me".My big takeaway from this is that the “self”, the “me”, the “I” is perhaps not some entity that was always there or somehow got attached to the body, rather it is the embodied experience itself which forms the mental construct of a “self” as we learn to model our own agency and learn how to navigate this world. Also, and this is key, we don’t do this on our own. It is through the care and touch of others that we come to be ourselves. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

The core argument of philosopher Daniel Kolak's book, I Am You, is that we are all the same person, or, more precisely, that a single subject (consciousness) is "incarnated" in all human beings. This idea, often called "Open Individualism" (OI), is not meant in a mystical sense, but as a logical and metaphysical possibility. According to Kolak, it's the most coherent explanation for who we are and provides the best metaphysical basis for global ethics.“But we sure seem separate”, one might say. Kolak addresses the various types of borders which we build around the concept of a person to show that we have all sorts of hidden assumptions behind these borders and they might not be as solid as they appear to be. In one sense there are borders we can draw to distinguish you from me, but in another sense, those borders are just constructs and not hard and fast boundaries that divide us into separate subjects. For instance:* Physical Borders - I seem to have a separate body from you.. yet my physical body is constantly changing over time and I don’t consider myself from last year as a separate person from myself at this moment* Spatial Borders- People seem to exist in different places… yet you are not “over there”, rather, you appear “right here” in me. The space between us is a construct of our mental map of the world. * Psychological Borders - Your mind appears separate from my mind.. yet if I have multiple personality disorder, am I to be considered as two people?I like the way this aligns with some of Douglas Hardings concepts of regional appearances in his Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth. At one level, in the 3rd person point of view, we can distinguish amongst multiple people. At other levels we can be viewed as the earth or as humanity. And from our own first person perspective, we are the alone, the no-thing full of every-thing. Having both views feels more complete than having one without the other. You are you, but also, I am you. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

Physicist John Archibald Wheeler, who coined such terms as “black hole”, “wormhole”, and “quantum foam” wrote about his concept of the “Participatory Universe” in the inspiration for today’s episode — Wheeler’s paper entitled Beyond the Black Hole.Wheeler describes his “delayed choice experiment” which shows that not only does an electron behave as a particle when observed and a wave when not observed, but that we can delay our choice in whether to observe it and then after making the choice, the electron will behave accordingly. Quantum strangeness like that implies that we as observers have a definite role in shaping the “reality” around us.Wheeler used the analogy of a letter R (for reality) made of papier-mâché where there are definite iron post observations that mark out the structure of reality, but we fill in the rest with our own theories based on those observations.But aren’t we a part of reality as well? In a way, yes, our human appearance is also a part of the reality we observe. In that way, Wheeler said, we are participating in our own creation. And this participation is not just on our own mental scale, but Wheeler says it extends to the whole universe as observed by all observers. Wheeler drew this iconic picture of the universe looking back at itself to illustrate his point. The Big Bang is the top right of the picture where the universe “U” then expands and ultimately creates observers (represented by the eyeball at top left) which can then look back at the whole history of the universe and thereby bring it into a sort of papier-mâché being.We play this role for the universe. We get what we look for. Looking down, I find a torso, arms and legs and the earth at my feet. Directing my attention to where those arms and legs and earth are sticking out of, I see just pure nothingness, the source where all that creation comes from and the subject which is the observer of that creation. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

Recently I had the thought “I’m not making things happen, the things that are happening are making me”. For me this resonates with what Alfred North Whitehead describes in his process philosophy as laid out in Adventures of Ideas. It is based on the insight that we are not static subjects observing static objects - everything is becoming rather than just being.Whitehead sees each moment of experience as a process where we don't simply "make things happen" - rather, we are constituted by how we prehend (take in and feel) what is given to us from the past. Whitehead calls the process of “concrescence” as the way these prehensions come together to form a new unity which he calls the “superject”.Whitehead uses the term “ingression” to describe how eternal objects (potentialities) and past actual occasions enter into and shape the becoming of each new moment of experience. We don't stand apart from experience and "make" it - we are made by it.Whitehead reverses the traditional subject-object relationship. Instead of a stable subject that acts on or perceives objects, he sees subjects as emerging from the process of experiencing. The experiencer and the experience arise together. This also relates to what Whitehead calls "creativity" - the ultimate principle by which "the many become one and are increased by one." The "many" (all the past occasions and potentials) come together to create each new occasion of experience, which then becomes part of the "many" for future occasions.We, and all of reality, are like a river. A constant flow of becoming, always changing, always new. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

18th century philosopher, David Hume’s essay entitled A Treatise Of Human Nature is the topic of today’s deep dive. Hume analyzes the role of memory and ideas in or own perception of the self. For Hume, there is an immediate “impression” we get from our perceptions that are then later recalled into fuzzier “ideas” about what we perceived. Impressions have a greater “force and liveliness” while ideas are “faint images” of impressions. Being an empiricist, Hume argues that we can find no concrete permanent entity called “the self”. Instead of we have a “bundle” of perceptions which we then connect together in an attempt to understand those events in terms of cause and effect. This forms the idea of the self to explain what happened. He uses the idea of a republic as an analogy for our idea of a self. Just as a republic is the idea of a collection of common persons with similar coordinated behavior, the self is likewise an idea arising from our bundle of perceptions.This reminds me of the phrase “the united cellular republic” that Douglas Harding uses sometimes as one way to describe what a person is. Tying Hume and Harding’s ideas together, I would say we are a cellular republic which refers to itself as “me”, “myself”, and “I”. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

This short story entitled Where Am I? by philosopher and cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett really made my head spin. It is the fascinating tale of a fictional character whose brain and body are separated by radio transmitters. So many questions and scenarios are played out and examined by Dennett in this story. Are we the body? Are we the brain? Are we just the point of view that comes from experience happening thru the body? There are no easy answers to these questions, but this was a really fun story and will hopefully give you as much to think about as it did me. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

Cognitive and computer scientist Douglas Hofstadter is best known for his Pulitzer Prize winning book Gödel, Escher, Bach, and his later book I Am a Strange Loop but today’s episode is a talk Hofstadter gave at Stanford in 2006 about how analogies are the “interstate freeway system of cognition” (to use his analogy). In this fascinating and humous lecture, Hofstadter shows how our use of analogy in language and the way we sometimes get tripped up and mix metaphors or blend words together points to the deep role analogy plays in our cognition. He suggests that perhaps it might be analogy all the way down. In a future episode we will further explore the role of analogy in Hofstadter’s “strange loop” concept and how building up a series of analogies eventually leads us to having a sense of “self”. But for today, enjoy this talk about how analogy plays a deep role in our thinking process. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

Princeton psychologist Julian Jaynes outlines his fascinating theory of the bicameral mind in this essay entitled Consciousness and the Voices of the Mind. Jaynes’ theory is that humans were not always conscious in the way we think of being conscious. Jaynes defines consciousness as the “mind space” we use as an analog of the real world and says we use metaphors to describe our introspection of what this inner model of the world is like. But Jaynes also says this has not always been the case. He cites early written works and cultural artifacts that indicate that as recently as 3000 years ago, humans experienced the world through what Jaynes calls a “bicameral mind”. Whereas today, we introspect our thoughts and see them as thoughts, to these early cultures those thoughts would appear as auditory hallucinations which they would attribute to the voices of gods speaking to them.Jaynes says that in the bicameral mind the right hemisphere acts as the “god” part which issues commands and the left hemisphere follows the commands without introspection. Jaynes says our modern way of thinking and introspection is a learned process, derived from language like “I see the solution” and “I’m feeling down”. Our sense of “I” comes along with this language as the subject that is doing the seeing and the feeling.This theory, although somewhat controversial, just makes me realize how much I take for granted and assume must have always been the way minds work. Even in our own lifetime we may even go through this same process of mental evolution. Jaynes compares the “imaginary friends” of some children to the personal gods of the bicameral mind and it does make sense that a lot of our own self-talk seems to be commands and judgements we are giving to ourselves. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

Douglas Harding’s description of the Heirarchy of Heaven and Earth was clearly influenced by Leibniz and Leibniz’s Monadology. In the Monadology Leibniz describes the concept of monads, where each monad represents the entire universe from a unique point of view. Harding says “what I am depends on the range of the observer”. And this implies that to really understand what I am (from a 3rd person perspective) you have to observe me from every possible angle and every possible distance, with every possible sort of sensory apparatus. This corresponds to the way Leibniz describes looking at the same town from different sides. Each monad has its own distinct perception of the universe, but they all ultimately reflect the same universe. So each of us, in our own way, contains the whole universe as a living reflection of the whole universe. Though we may seem limited due to our limited perspective, in our very essence we are all whole and complete, lacking nothing.“Now this connexion or adaptation of all created things to each and of each toall, means that each simple substance has relations which express all the others,and, consequently, that it is a perpetual living mirror of the universe”. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

Philosopher Bernardo Kastrup takes the “hard problem of consciousness” and completely turns it inside out. Kastrup’s PhD dissertation titled Analytic Idealism: A consciousness-only ontology, argues that consciousness is fundamental. Everything supposedly “material” (including our bodies and brains) are appearances in consciousness.Kastrup uses the concept of alter-egos to describe how we all appear to have our own individual consciousnesses. It is not that we are separate individuals with our own bodies and our own minds, but rather that each of us is one of the many “alters” in a universal consciousness and that “others” are what the other alters look like from the perspective of our own alter.According to Kastrup, this explains away the “hard problem”. Instead of the traditional view that brain activities are the neuronal correlates of consciousness - e.g. proof of the brain generating thoughts, the opposite may be true. Brain activity is actually just what the mental process of one “alter” looks like to another alter.I find this to also be a beautiful way of thinking about “the one” and “the many”. At one level we are many minds, but at another level we are one mind. Wouldn’t that totally change the nature of disagreement in this world if we took seriously the idea that “they” are really “me” experiencing different thoughts? This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com

In his article, On the Nature of Time, Stephen Wolfram describes the computational model he has for the universe and how that results in a new way to look at time. Wolfram is a physicist, computer scientist, author, inventor of Mathematica (software used by scientists and engineers) and Wolfram Alpha (the brains behind Siri) so he knows a thing or two about computation and physics. He has been spearheading a project called The Wolfram Physics Project where they have been building a model of the universe based on computation.The way I think of this model is that there is what Wolfram calls “The Ruliad” which is the set of all possible rules for all possible universes, and then there is a huge dataset where every point of space exists and gets updated by running through the rules, or actually, running through all possible rules and then getting all possible points of space. We, as observers, are or course included in all that exists as well and we see our section of this process that is local to our section of space unfolding according to our section of all possible rules.But what is time? In this article, Wolfram describes that as these rules unfold and are computed we see the “future” unfolding before our eyes as the next set of states for everything that exists. However, since our brains can only compute at a certain rate and that rate is much smaller than the rate of everything unfolding in the ruliad computations, we end up with summarized snapshots of the universe that unfold before us like a movie made of so many images per second instead of as a stream of countless bits of information.Wolfram summarizes it as follows:“In our everyday life we’re typically looking at scenes involving objects that are perhaps tens of meters away from us. And given the speed of light that means photons from these objects get to us in less than a microsecond. But it takes our brains milliseconds to register what we’ve seen. And this disparity of timescales is what leads us to view the world as consisting of a sequence of states of space at successive moments in time. If our brains “ran” a million times faster (i.e. at the speed of digital electronics) we’d perceive photons arriving from different parts of a scene at different times, and we’d presumably no longer view the world in terms of overall states of space existing at successive times.”So according to this theory, it seems that time is just what it feels like to see one snapshot after another in a certain sequence. We are starring in, and projecting the movie of our lives. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit headlessdeepdive.substack.com