Discover The Eurasian Knot

The Eurasian Knot

The Eurasian Knot

Author: The Eurasian Knot

Subscribed: 1,974Played: 35,263Subscribe

Share

Copyright © The Eurasian Knot 2023

Description

To many, Russia, and the wider Eurasia, is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. But it doesn’t have to be. The Eurasian Knot dispels the stereotypes and myths about the region with lively and informative interviews on Eurasia’s complex past, present, and future. New episodes drop weekly with an eclectic mix of topics from punk rock to Putin, and everything in-between. Subscribe on your favorite podcasts app, grab your headphones, hit play, and tune in. Eurasia will never appear the same.

Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

349 Episodes

Reverse

Joseph Stalin died today, March 5, seventy-three years ago. So, I thought it would be a good idea to dig out, re-edit and remaster, the interview I did with Joshua Rubenstein back in 2018 about the dictator’s final days. What did Stalin focus on in the final years of his life? How did Soviet leadership react to his death? Soviet society? And internationally? Let’s revisit what Rubenstein had to tell us from his book, The Last Days of Stalin.Guest:Joshua Rubenstein is an associate of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University. He’s the author of several books on Soviet history. His most recent is The Last Days of Stalin published by Yale University Press. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

When societies are in crisis, people tend to seek alternative belief systems to give them comfort, explain a complex world, or fill a space left vacant by discredited ideologies and faiths. Like the embrace of spiritualism after the mass death during the American Civil War. The growth of millenarian movements and cults for fear of the end times. Or even the embrace of conspiracy theories to explain the unimaginable. The Soviet Union was no exception. As the system broke apart and Marxism-Leninism was tossed aside, a questioning of dominant narratives took root. Soviet citizens began to seek new belief systems–astrology, gurus, alternative medicines, sects and cults, and fantastical historical narratives. Joseph Kellner was struck by this explosion of belief seeking and wanted to understand it. Why did Russian citizens gravitate to new forms of belief? What was lost with the collapse of the Soviet system and what opportunities did a new society offer? And what does this all say about the need for humans to believe in, well, something? The Eurasian Knot spoke to Joseph about his book, The Spirit of Socialism: Culture and Belief at the Soviet Collapse, to get a sense of this urge to embrace new beliefs and how they shaped experience during the collapse of the Soviet Union.Guest:Joseph Kellner teaches Russian and Soviet history at the University of Georgia. He’s the author of The Spirit of Socialism: Culture and Belief at the Soviet Collapse published by Cornell University Press. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

As a Cold War kid, I remember the intense rivalry between the United States and USSR during the Olympics. Of course, we remember the US’ boycott in 1980 because of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. And the Soviet boycott in 1984 in response to the American boycott. Who bested who was not just about national pride. It was a testament as to who had the better system: communism or capitalism. What I didn’t know then was that for Moscow, winning was everything. Losing came with consequences. Why was it so important for the Russians to win? So much so, as we saw a few years ago, at the risk of being banned for a state-run doping operation? These are just a few questions the Eurasian Knot posed to Bruce Berglund, author of The Moscow Playbook: How Russia Used, Abused, and Transformed Sports in the Hunt for Gold. I’ve never been much of an Olympic watcher (my sport is the NBA), but now I better understand why that hunt for gold is such a Kremlin obsession.Guest:Bruce Berglund is a historian of Europe, Russia, and world sports and teaches at Charles University in Prague. He’s written several books on sports, including The Fastest Game in the World, a global history of hockey. His new book is The Moscow Playbook: How Russia Used, Abused, and Transformed Sports in the Hunt for Gold published by Triumph Books. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

A quick scan of the hundreds of books on US-Russia relations gives the impression that the two countries only met in the 20th century. But relations go back to the early days of the American republic. And, surprisingly, throughout most of the 19th century, the United States and Russia were amicable powers joined in their mutual suspicion of Britain. Relations only began to deteriorate as the US increasingly entered global politics beyond the western hemisphere. What was the historical nature of American and Russian encounters? How did the relationship ebb and slow between distant friends and initiate enemies? And how did this dynamic shape self and bilateral perceptions? The Eurasian Knot turned to three of the best historians on the subject, Victoria Zhuraleva, Ivan Kurilla, and David Foglesong to talk about their new book, Distant Friends and Intimate Enemies: A History of American–Russian Relations about long history of the US-Russia dance.Guest:David Foglesong is a professor of history at Rutgers University. Ivan Kurilla is a visiting professor at Ohio State University. In 2024, he left Russia after being dismissed from the European University at St. Petersburg for opposing the war in Ukraine.Victoria Zhuravleva is Professor of American History and International Relations and Chair of the Department of American Studies at Russian State University for the Humanities.Together they are the authors of Distant Friends and Intimate Enemies: A History of American–Russian Relations published by Cambridge University Press. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

The history of borders and nations in Eastern Europe is fraught. What we even call the region is a site of contestation. Is it “Eastern Europe,” “Central Europe,” or “East Central Europe”? For Pitt historian Gregor Thum, space and how it’s delineated matters. This is especially the case for Germany and its eastern borderlands and people. Empire, war, ethnic cleansing, and shifting borders have left their marks on regional identity and memory. To the point, as Thum explains, a simple photograph he took in Poland can be interpreted with suspicion. How did the German empire regard its east? How do its shifting borders continue to live with us today? And how do we wrestle with the fractured memories that inhabit the national bricolage of Eastern Europe? The Eurasian Knot spoke to Gregor Thum to highlight his scholarship for a Pitt REEES Faculty Spotlight.Guest:Gregor Thum is an Associate Professor in the History Department at the University of Pittsburgh. He specializes in the history of empire, forced migration and memory in Central Eastern Europe. He’s the author of Uprooted: How Breslau became Wrocław during the Century of Expulsions published by Princeton University Press. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

What is Russia? There’s no easy answer. Travelers, scholars, philosophers, and journalists have pondered the question for centuries. And though answers vary, there is one point of consensus–whatever Russia is, you won’t find it in large cities. “Russia” exists out there, deep in the countryside, in the small towns and villages. For journalist Howard Amos, Russia begins in the provincial city of Pskov. “Russia Starts Here” is its slogan, and Amos uses it to pry open the lives of the region's citizens in his first book, Russia Starts Here: Real Lives in the Ruins of Empire. Amos conducted over 30 interviews during his decade stint in Russia until he left after its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. There’s the elderly couple who are the last of their village. The shattered young family whose’ father was killed in Ukraine. The oppositionist politician that risks it all to push back against Putin. And the priest, Father Tikhon Shevkunov, Putin’s supposed “spiritual father.” The Eurasian Knot spoke to Amos about his reporting and being a reporter in Russia, what people told him about daily life, the war in Ukraine, and where the country’s been and where it's going. Did Amos find Russia? Maybe just a snapshot. The country is just too big and too complex for anything more.Guest:Howard Amos is a writer and journalist who spent a decade as a correspondent in Moscow. He left Russia in the days after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and, based out of Armenia, did a year-long stint as editor-in-chief of The Moscow Times in exile. His first book is Russia Starts Here: Real Lives in the Ruins of Empire published by Bloomsbury Continuum. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

A decade ago, Vladimir Alexandrov published an excellent biography, The Black Russian, about an unknown historical figure–Fredrick Bruce Thomas. Thomas was a Black Mississippian who moved to Imperial Russia and became a successful Moscow nightclub owner until Revolution forced him to flee. Thomas’ life is a window into post-emancipation Black American aspiration, struggle and cosmopolitanism. Alexandrov found Thomas such an intriguing character, he couldn’t let him go. So now, Thomas is the principle in a suspense novel set in Russia’s Silver Age. The Eurasian Knot spoke to Alexandrov about Thomas’ new adventure, the challenges of writing a novel, and where can we expect Fredrick Bruce Thomas to go from here. Guest:Vladimir Alexandrov, B. E. Bensinger Professor Emeritus in the Slavic Department at Yale, is the author most recently of The Black Russian, and To Break Russia's Chains: Boris Savinkov and His Wars against the Tsar and the Bolsheviks. He is currently completing a history of Russian involvement in the American Civil War, and the second novel in The Black Russian series. His first novel is The Black Russian and the Serpents Sting published by NIMCA Press. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Alexander II’s Great Reforms were sweeping. They freed over 22 million serfs, overhauled the judicial, university, and municipal systems, and loosened censorship, among others. It was one of those pivot points in Russian history. If successful, Russia would have charted a more liberal path or stay on the autocratic road if a failure. Most historians have ruled them a failure. But what were the reforms trying to accomplish? What kind of Empire did it seek to create? Could they turn subjects of an autocracy into citizens of a nation? To discuss such a “big topic,” the Eurasian Knot spoke to Tatiana Borisova about her research into Alexander’s judicial reforms and their historical consequences. Can Russia’s attempt at reform in the mid-19th century provide some hope for a different Russia in the future?Guest:Tatiana Borisova is an Associate Professor of History at the Higher School of Economics St. Petersburg. Her most recent articles in English include: “Imperial legality through ‘Exception’: Gun control in the Russian Empire” and, with Jane Burbank, “Russia’s Legal Trajectories.” She co-edited, The Legal Dimension in Cold-War Interactions: Some Notes from the Field. Her newest book, in Russian, is Когда велит совесть: Культурные истоки Судебной реформы 1864 года в России published by Новое литературное обозрение. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

I love street art. And I don’t care in what form. Beautifully crafted murals. Spraypainted gang tags. Scrawls on bathroom stalls. Even guerilla sticker mosaics on streetlights. I especially like how street art alters the narrative of a space. So, I was excited when I received a copy of Alexis Lerner’s book, Post-Soviet Graffiti. Post-Soviet street art has gotten little scholarly attention making the topic ripe for exploration and discussion. Post-Soviet graffiti shares a lot with its global counterparts–similar aesthetics, themes, culture, and political edginess. It also shares attempts at its co-optation by governments and corporations. But what makes political street art different in authoritarian countries like Russia? Is its power to circumvent media censorship and political control? What is street art, anyway? Who are the artists? And does graffiti have a political impact? The Eurasian Knot spoke to Alexis to get her thoughts and discuss the content and form of some of the graffiti she’s encountered over the last decade.Guest:Alexis Lerner is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the United States Naval Academy. She’s the author of Post-Soviet Graffiti: Free Speech in Authoritarian States, published by University of Toronto Press. You can see the Alexis’ gallery of graffiti at https://postsovietgraffiti.com/ Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

A new youth subculture emerged in the Soviet Union in the late 1940s and early 1950s–the Stiliagi. Roughly translated as “the stylish,” these youths, the majority of whom were men, wore flashy hairstyles and bright colored clothes, danced to jazz, and were obsessed with Western aesthetics. And of course, this style broke Soviet conventions, challenged social norms, and expanded gender performance. Though the exact origin of the Stiliagi is murky, it arose alongside other Western youth subcultures–the beatniks, the mods, the rockers–of the immediate post-WWII libertinism. The Stiliagi put the Soviet Union squarely within the history of a more globalized youth culture. But, what did it mean to be a “stiliagi”? Who were they? How did the style offer alternative forms of Soviet masculinity? How did the Soviet authorities react to these youths? And how did this subculture differ from its Western counterparts? The Eurasian Knot spoke to Alla Myzelev about her new book on the subculture, Stiliagi and Soviet Masculinities, 1945–2010: Fashion as Dissent, to get some answers.Guest:Alla Myzelev is a Professor and Chair of the Department of Art History and Museum Studies at SUNY Geneseo. She is currently editing a book titled Challenging Imperial Narratives Through Visual Art and Material Culture in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Her new book, Stiliagi and Soviet Masculinities, 1945–2010: Fashion as Dissent, is published by Manchester University Press. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Soviet ideology called for the emancipation of women. Soviet women would be active participants in public life, unburdened by the home, children, and husbands, and serve equally in the building and defense of the Soviet state. Reality, however, was different, especially during WWII. Soviet women did serve in the Red Army and partisans. But life at war was more than the heroic tales we know today. Soviet women were often abused by their commanders and fellow soldiers or viewed as suspicious, weak, and even dangerous. Life under occupation was even worse. Many women turned to “survival prostitution” and fraternized with German soldiers to escape abuse, forced labor, and death. What strategies did Soviet women adopt to survive the war? How were they looked upon by the enemy, their neighbors, and compatriots? And what happened after the war to those who formed sexual relations with German soldiers? The Eurasian Knot spoke to Regina Kazyulina about gender, sex, and survival to get a window into this contentious and understudied chapter of WWII in the Soviet Union. Guest:Regina Kazyulina is a visiting assistant professor of history and the assistant director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Salem State University. Her book, Women Under Suspicion: Fraternization, Espionage, and Punishment in the Soviet Union During World War II published by University of Wisconsin Press. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

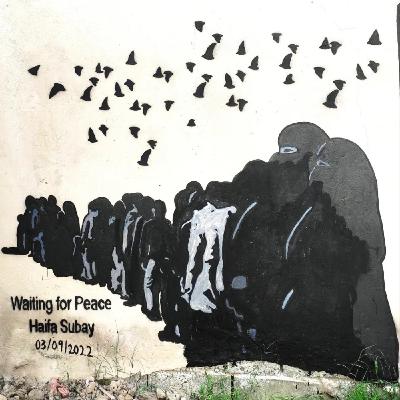

About two years ago, I was brought on to a podcast project started by the Global Studies Center at the University of Pittsburgh. The initial pitch was to produce a student-led podcast featuring two threatened artists that are part of the Pittsburgh Network for Threatened Scholars (PiNTS). I’m proud to feature the end result, The Art of War. It features two artists, the Yemeni street artist, Haifa Subay, and the Ukrainian poet, filmmaker, and musician, Oleksandr Fraze-Frazenko, about exile, art, war, and adjusting to life in Pittsburgh. I hope Eurasian Knot listeners enjoy it because I’m really proud of having been a part of it. And especially, seeing how our students, Jojo Ellis, Kyla Parker, and Lily Acharya proved to be naturals in the audio craft.Art of WarProduced by Lily Acharya, Jojo Ellis, Kyla Parker, David Greene, Shannon Reed, and Sean Guillory.Editing and sound design: Sean GuilloryMixed and mastered; Daniel Cooper, Podcuts EditingMusic: Blue Dot Sessions Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

What is peat? We had no idea until the Eurasian Knot spoke to Katja Bruisch about how this coal-like soil was an energy source in Russia and the Soviet Union. Found in wetlands, peat is the extracted top soil that is dried and burned for fuel. It was a marginal, but important, energy source in industrialization. Peat was also used as a localized source to produce electricity for Lenin’s Electrification campaign. Because, as the old man put it, “Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country.” But, Bruisch tells us, extracting peat was labor intensive, and into the Soviet period, increasingly done by women. Peat harvesting created communities and culture. It also significantly altered local ecologies. How crucial was peat in modernization? Why was it used instead of other energy sources? And can it serve as a present-day alternative? The Eurasian Knot posed these questions and more to Katja Bruisch about her book, Burning Swaps: Peat and the Forgotten Margins of Russia’s Fossil Economy published by Cambridge University Press.Guest:Katja Bruisch is an environmental historian at Trinity College Dublin interested in energy, resource extraction and land-use in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. Her new book is Burning Swamps: Peat and the Forgotten Margins of Russia’s Fossil Economy published by Cambridge University Press.Send us your sounds! PatreonKnotty News Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

I’ve grown to admire historians like Catherine Merridale. You know, those historians who buck academic conventions to write for a non-academic audience. This was quite a change for me since I used to hold such work in contempt (or was it jealousy) when I was a snot-nosed, snobby grad student. So I jumped at the chance to interview Merridale and talk about the historical craft and its relationship to detective fiction in her first novel, Moscow Underground. As she explains, there’s some liberation in fiction. You can freely develop characters. Imbibe the story with emotions, the sites, the sounds, the smells. And craft a compelling and entertaining story. But creative license has its limits. Historical fiction requires you to stick to the historical record. You have to make sure the history you set your story in is believable, as Merridale does, in her crafting of Moscow of 1934. What challenges does writing fiction present to a professional historian? How does fiction and history intersect? And why a novel at all, let alone a detective novel? The Eurasian Knot spoke to Catherine Merridale about her hero, Anton Markovich Belkin, an investigator for the Procuracy, and the murder investigation that takes him into Moscow’s two undergrounds–the metro and the underbelly of crime, poverty, and politics in her first novel, Moscow Underground. Guest:Catherine Merridale is an acclaimed historian of Russia and the Soviet Union. Her work includes pioneering oral history as well as archival research on topics as varied as death, the Kremlin, and Lenin's train ride of 1917. With Russia now off-limits for political reasons, she now turns to fiction. Moscow Underground is her first novel, set primarily in 1934.Send us your sounds! PatreonKnotty News Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

The Prussian city of Konigsberg is well-known as the birthplace of Immanuel Kant. But in many ways it’s also a microcosm for the twentieth century. Founded in the 13th century by Teutonic knights, the city served as a key trading center for the Prussian Empire until the Polish corridor severed it from Germany after WWI. It is then that the history of Konigsberg takes an even more dramatic turn. Its “Germanness” became an object of debate and political exploitation. By the early 1930s, it had one of the highest votes for the Nazis in Germany. But then–WWII. Destroyed and depopulated by 1944, it became the first city to satisfy the Red Army appetite for revenge rape and pillaging. It became a Soviet possession after WWII and, like the rest of Eastern Europe, was sovietized into Kaliningrad. And even though the USSR is no more, it remains a part of the Russian Federation.The history of Konigsberg/Kaliningrad begs so many questions. Why Nazism? What was life there during the war? The Red Army violence but also its reconstruction into Kaliningrad? How did the Soviets handle their mortal German enemies after a war of annihilation? And how is this legacy seared into the city? The Eurasian Knot wanted to know more and turned to Nicole Eaton to learn more about her book, German Blood, Slavic Soil: How Nazi Königsberg Became Soviet Kaliningrad.Guest:Nicole Eaton is Associate Professor of History at Boston College where she teaches courses on the Soviet Union, Imperial Russia, modern Europe, authoritarianism, and mass violence. She’s the author of German Blood, Slavic Soil: How Nazi Königsberg Became Soviet Kaliningrad published by Cornell University Press. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

I’ve been thinking about the use of “they” in our political rhetoric. In some respects, this third-person plural pronoun is indicative of politics. The “they” in politics often refers specifically to an entity–political party, a group of politicians, etc. But what if the “they” refers to another nebulous entity? For example, here’s a clip from a recent NYT Daily episode on Charlie Kirk’s memorial: “They also had a goal of gaining control of the media and Hollywood so they could change the culture in America. They kill and terrorize their opponents, hoping to silence them.”Who is this “they”? This reminded me of an interview I did with Paul Hanebrink from 2019 about his book A Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-Bolshevism. Hanebrink gives a good history of one “they” that is at the center of the Judeo-Bolshevik myth–a conspiracy that I think is the foundation of most conspiracy thinking–a shadowy “they” that is behind all social ills. How has the Judeo-Bolshevik myth shaped the 20th century? How did it change over time? And what resonance does it have today? To get some insight, give this interview with Paul Hanebrink another go.Guest:Paul Hanebrink is a Professor of History at Rutgers University specializing in modern East Central Europe, with a particular focus on Hungary, nationalism and antisemitism as modern political ideologies, and the place of religion in the modern nation-state. He’s the author of In Defense of Christian Hungary. His most recent book is A Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-Bolshevism published by Harvard University Press. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

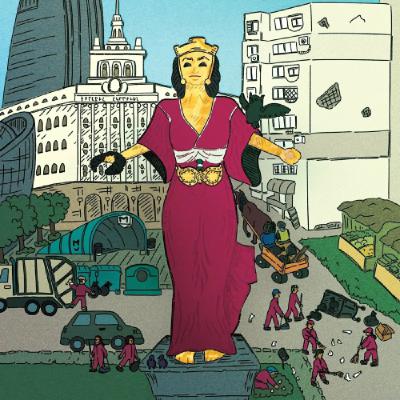

There’s a paradox at the center of Elana Resnick’s book, Refusing Sustainability: Race and Environmentalism in a Changing Europe. EU policies of environmental sustainability in Bulgaria require the racialization of Romani into a permanent low-skilled and impoverished workforce. Waste management required teams of Romani streetsweepers and trash collectors to sort trash into waste, recyclables and compost, and bring them for processing and reuse. This labor was historically filled by Bulgaria’s Romani citizens, to the point where white Bulgarians equated them with waste. And in turn, Roma’s racial otherness allowed white Bulgarians to enter a pan-European concept of whiteness. Since race is a favorite subject on the Eurasian Knot, Sean spoke to Elana about Sofia’s Romani women as waste workers, the powerful solidarity and collective action that emerges from their labor, and the implications for Romani rights struggle in Bulgaria.Guest:Elana Resnick is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she also leads the Infrastructural Inequalities Research Group. She’s the author of several articles and the book, Refusing Sustainability: Race and Environmentalism in a Changing Europe, published by Stanford University Press.Send us your sounds! PatreonKnotty News Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

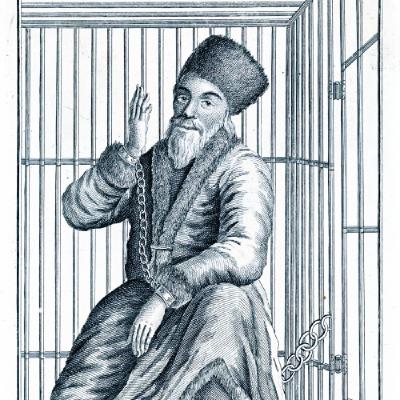

There are many stereotypes about Russia. But perhaps one of the strangest is that Russians prefer a strong hand, are politically passive, even apolitical, and rebellion just isn’t in their DNA. This belief requires a hefty dose of historical amnesia. Many of Russia’s most memorable historical figures–Stenka Razin, Pugachev, the Decembrists, the People’s Will, Lenin, Sakharov, Alexei Navalny, to name a few, were rebels. Not to mention, Russia has experienced three revolutions over the last century–1905, 1917, and 1991. Rebellion, in fact, is an integral part of Russia’s history, and the rebel often leads the dance with the Tsar. What is rebellion? Who are these rebels? What makes them? And how do they shape the Russian political system? These are questions that resonate in Russia and beyond. So the Eurasian Knot invited Anna Arutunyan on the pod to discuss the figure of the rebel in her new book, Rebel Russia: Dissent and Protest from Tsars to Navalny published by Polity.Guest:Anna Arutunyan is a Russian-American journalist, analyst, and author. She served as senior Russia analyst for the International Crisis Group before leaving Russia in 2022 and is the author of five books about the country, its politics, society and wars. Her new book is Rebel Russia: Dissent and Protest from Tsars to Navalny published by Polity. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

After 1917, San Francisco’s small Russian community exploded with new arrivals. Over the next decade, thousands quit Soviet Russia, often via the Far East or China, to escape revolution and civil war. Arrival in America, however, was only the beginning of new trials. In the 1920s and 1930s, American nativists saw Slavic people as low in the racial hierarchy–people who were visually white, but culturally not quite. The Russian community in San Francisco was faced with a contradictory choice: to preserve their culture, a culture that they saw was being destroyed in Soviet Russia or shed their Russianess and become more “American” i.e. more “white.” How did this first wave of Russian emigres meet the challenge of otherness and assimilation? And what about the second wave of Russians who came after WWII? How did they navigate the Red Scare where Russian was equated with communist and the notions of Americanness had become more polarized? The Eurasian Knot spoke to the historian Nina Bogdan about her new book, Before We Disappear into Oblivion: San Francisco’s Russian Diaspora from Revolution to Cold War, to get some insight.Guest:Nina Bogdan is a historian and cultural preservationist. She recently authored the “Russian American Historic Context Statement” for the San Francisco City Planning Department as part of the Citywide Cultural Resources Survey. She’s the author of Before We Disappear into Oblivion: San Francisco’s Russian Diaspora from Revolution to Cold War published by McGill-Queen’s University Press.The article Rusana mentions on the history of Berkeley's Institute of Slavic Studies is here. However, the piece is about the historian Robert J. Kerner, not Nicholas Raisanovsky. Send us your sounds! PatreonKnotty News Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

What power do jokes have in authoritarian societies? I’ve been thinking about this recently as Trump further consolidates power. Turn on any American late night show and it’s one joke about Trump after another. It’s easy for comedians. The Trump jokes write themselves. Soviet Russia didn’t have late night, and openly poking fun at the authorities was highly circumscribed. This continues to a large extent in today’s Russia. But people still tell biting, insulting jokes in daily life. Laughing at power can’t be totally contained. But do they matter? What power do they have? In what ways are they criticism of the powers that be, a way to cope with the absurdity of everyday life, and or merely self-delusional exercises in political agency? All three? In 2018, the Eurasian Knot took on these questions about jokes in a conversation with Jon Waterlow about his book, Only A Joke, Comrade! Humor, Trust, And Everyday Life Under Stalin, 1929-1941. We decided to rerun the interview for what it can tell us about our present conjecture.Guest:Jon Waterlow received his PhD in History at Oxford. He’s the author of It's Only A Joke, Comrade! Humor, Trust, And Everyday Life Under Stalin, 1929-1941. Jon is also host of the podcast Voices in the Dark. Look for it on your favorite podcast feed. Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

Awkward

Excellent program

good