Discover ICTalk: Infection Control Today Podcast

ICTalk: Infection Control Today Podcast

ICTalk: Infection Control Today Podcast

Author: ICTalk: Infection Control Today Podcast

Subscribed: 3Played: 21Subscribe

Share

Description

ICTalk: Infection Control Today Podcast is a podcast that dives into the latest trends, challenges, and solutions in infection prevention and control. This podcast delivers expert insights, real-world strategies, and actionable advice, covering topics relevant to health care professionals at every level—from C-suite executives to infection preventionists, sterile processing, environmental hygiene staff, and more. Join us for conversations with leading infection preventionists, industry experts, and thought leaders as we explore how to create safer environments, improve outcomes, and navigate the evolving landscape of infection control.

17 Episodes

Reverse

Few issues embody the intersection of prevention, compassion, and communication more than HIV and PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis)—subjects that remain clouded by stigma, even decades after the epidemic’s darkest days. I recently spoke with Cariane Morales Matos, MD, medical director at Hope & Help of Central Florida, about how health care providers, parents, and infection preventionists can approach these conversations, especially with teens, with clarity and empathy.

“Fear and stigma get attached to subjects related to sexual health,” Morales began. “We need to move away from the fear and the stigma and just start having these conversations like we would talk about anything related to our general health maintenance.”

That normalization, she explained, is key. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends HIV screening for everyone between the ages of 18 and 65, which is a higher rating than even routine blood pressure checks. Yet HIV is still often whispered about, creating unnecessary barriers to prevention. “It should be exactly the same,” Morales said. “We need to take the fear away from it so that we can start having conversations that are solely based on prevention and just trying to set us up for a successful, healthy life.”

For those unfamiliar, Morales offered a quick refresher:

“HIV is a sexually transmitted infection… The only way that you can get this infection is through sharing bodily fluids that have high amounts of the virus.” AIDS, she noted, is the advanced form that develops only without treatment. “Right now, we have so many great therapies that even if you were to get diagnosed with HIV, you can have a healthy, long life…by just taking one pill a day.”

She went on to explain PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis, a medication that reduces the risk of infection by up to 99%. “We have 2 approved oral medications and 2 injectable medications… there’s literally an option for everybody,” she said. “It’s about starting this conversation with your provider and finding the right fit for your lifestyle.”

Still, starting that conversation, especially with adolescents, can be daunting. “The first step… is reckoning with what you think these issues are, and finding what your biases might be,” she advised parents, educators, and health care professionals. “If you have doubts or uncomfortable feelings, that’s going to translate. Once you’re able to talk about this like you’re talking about going out to dinner or seeing friends—that’s the level of comfort you need.”

She also emphasized that HIV does not discriminate. “It has nothing to do with who you’re having sex with,” she said. “If you are somebody who’s having unprotected sex, that is your risk factor. We have to move away from, ‘I’m not that person.’”

For reliable information, Morales recommended the CDC’s HIV and PrEP resources, or local organizations like Hope & Help, which host community sessions and provide educational materials.

Her final message was simple but powerful: “It’s okay to be uncomfortable, it’s okay to be fearful, but it’s important not to shy away from asking these important questions. Knowing your status is the first step.”

In the end, talking about HIV and PrEP is not just about science; it is about breaking the silence. As Morales reminded Infection Control Today’s audience, information saves lives, but conversation opens the door.

When most people think of infection prevention, they picture data dashboards, surveillance reports, and regulatory checklists. But ask any experienced infection preventionist (IP) what really determines success, and you’ll hear something different—it is the people skills.

During a recent Infection Control Today® roundtable, veteran infection prevention professionals representing diverse roles and backgrounds reflected on the nonclinical skills that shaped their careers, the lessons learned the hard way, and the advice they would give to new IPs entering the field.

Their message was clear: Technical expertise may get you in the door, but emotional intelligence, communication, and systems thinking keep the door open.

Learning to Communicate Upward — and Effectively

“Short and sweet and to the point,” began Joi A. McMillon, MBA HA, BSN, CRRN, WCC, CIC, CJCP, HACP-CMS, AL-CIP, the CEO of JAB Infection Control Experts. “I wish I had understood better how to communicate effectively.”

She was reflecting on the early days of her career. “When I came in, I was very young and very passionate, but I didn’t have a mentor. I didn’t have anyone to help me translate that passion into communication that resonated with leadership,” she said. “When you’re not able to communicate effectively, you’re not just holding yourself back, you’re holding the entire program back.”

Her experience underscores a common challenge for new IPs who may know the science inside out but struggle to gain traction with the C-suite. Infection prevention is a field where evidence meets advocacy, and communication gaps can mean stalled initiatives or lost resources.

Emotional Intelligence: The Quiet Skill That Changes Everything

ICT contributing editor Carole W. Kamangu, MPH, RN, CIC, the CEO, founder, and principal infection prevention strategist for Dumontel Healthcare Consulting, took that point further, stressing the importance of self-awareness and emotional intelligence.

“I wish I had realized earlier that I needed emotional intelligence,” she said. “I was naturally good at challenging the status quo, but early on, I wasn’t doing it effectively. I knew what I wanted to change, but I didn’t always communicate it in a way that kept people engaged. When someone pushed back, I would take it personally and have the worst day.”

It took her years, she admitted, to learn to pause before entering a unit and ask herself: How am I feeling? How are they likely to react? That reflection transformed her interactions from combative to collaborative. “It’s about being aware of your own emotions before you even start the conversation,” she said. “That’s when productive dialogue can actually happen.”

Don’t Take It Personally — Take It Professionally

Lerenza L. Howard, DHSc, MHA, CIC, LSSGB, manager of infection prevention and quality improvement at La Rabida Children’s Hospital in Chicago, added another layer to the conversation: perspective.

“In the professional world, don’t take it personal,” she advised. “As IPs, we’re partnering with a multitude of stakeholders, all with competing priorities. You need emotional intelligence and effective communication to empathize with that, and still strategically navigate your initiative to the finish line.”

She emphasized systems thinking — understanding how infection prevention fits into the larger operational web of a hospital. “Knowing where your department fits in helps you propose initiatives and request resources more effectively,” she said. “It’s not just about infection control. It’s about how infection control supports the system as a whole.”

Top Three Skills for Every IP

When asked for her essentials, Nathaniel Napolitano, MPH, the CEO of Nereus Health Consulting and a health care epidemiologist for Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, Washington, didn’t hesitate.

“Interpersonal communication for relationship management — that’s number 1. Otherwise, nothing gets done, or it gets done painfully,” she said. “Number 2: confidence in decision-making. Trust your gut. And number 3: creative problem-solving. Because you will face problems you never imagined would fall within your scope.”

Kamangu quickly added with a laugh, “Nathan is a very creative person. I love working with him,” highlighting that creativity isn’t just a “nice to have” in infection prevention; it’s survival.

The Ripple Effect of Systems Thinking

Echoing earlier remarks, Missy Travis, MSN, RN, CIC, FAPIC, a consultant for IP&C Consulting and a former nurse, described the “ripple effect” mindset as essential.

“Realize it’s not all about you,” she said. “What you do has a ripple effect. We’re all connected. What I do affects you, and what you do affects me. That awareness changes how you communicate — it makes you listen as much as you speak.”

Her point struck a chord with the group: infection prevention doesn’t exist in isolation. It depends on relationships, interdepartmental trust, and shared accountability.

Say It So They Can’t Misunderstand It

Then came one of the most memorable takeaways of the session, from Garrett Hollembeak, CRCST, CIS, CHL, CIC, system infection preventionist for medical device reprocessing at Bon Secours Mercy Health in Cincinnati, Ohio

:

“There’s a difference between saying something so the person understands and saying something so they can’t misunderstand it.”

Too often, she said, communication breakdowns happen even when everyone has good intentions. “You send the email, you tell them what to do, and then it doesn’t happen,” she said. “So ask yourself: Is there any other way this could be misunderstood? It may take a few tries [to figure out a way.]”

Perseverance and Mentorship for New IPs

As the discussion shifted to advice for new IPs, Howard, offered a story of resilience. “It took me years to transition into infection prevention,” she shared. “My background was in medical technology, and every application came with rejection. But perseverance is key. Keep applying, keep connecting, and get strategic.”

She credited mentorship and networking with making the difference. “Join your local APIC chapter, reach out for informational interviews, shadow an IP if you can,” she said. “Put a face to your name. Even if you’re not in the IP space yet, start building those relationships.”

Taking Initiative and Building Confidence

Kamangu followed up with advice rooted in experience: “For aspiring or new IPs, taking initiative is key,” she said. “You have to learn to be independent quickly. Get involved in a project — even if it scares you.”

She recalled volunteering for a Candida auris project at her facility without knowing where to start. “That project…boosted my self-confidence.” She said that if you don’t take initiative, imposter syndrome will take over. You’ll always stay in the background.

The Power of Mentorship and Paying It Forward

Returning to the theme of guidance, McMillon emphasized how much mentorship would have changed her early trajectory. “If we’d had programs like this back then, we would’ve avoided a lot of [struggle],” she said. “Mentorship helps you navigate the challenges of the role, communicate effectively, and challenge the status quo professionally.”

She paused and added warmly, “As a mentor now, it’s so fulfilling to know you can be that difference-maker in someone’s career — to empower them to step up, no matter their…background.”

Expect the Unexpected

“Be dynamic and expect disruption,” said Napolitano, drawing laughter from the group. “What’s on your calendar might not be what you end up doing. That one thing that pops up could become your focus for the next week — or the next 5 years.”

Lifelong Learning and Self-Reflection

To that, Hollembeak added, “Learn whatever you can. Every advancement we’ve made in public health and infection prevention started with someone discovering something new. Take the webinars, read the textbooks, soak up every bit of knowledge.”

And Travis closed the loop with humor and wisdom: “As my kids say, I grew up in the 1900s. We used to say, ‘Check yourself before you wreck yourself.’ That’s my advice.”

The Takeaway: IPs as Leaders, Not Enforcers

Infection preventionists often wear the hat of educator, advocate, diplomat, and crisis manager — all before lunch. What unites the best among them, this panel revealed, isn’t just what they know, but how they connect.

From emotional intelligence and mentorship to creative problem-solving and perseverance, the modern IP isn’t defined by sterile technique alone, but by their ability to lead through influence and empathy.

Bug of the Month helps educate readers about existing and emerging pathogens of clinical importance in health care facilities today. Each column explores the Bug of the Month's etiology, the infections it can cause, the modes of transmission, and ways to fight its spread. The pathogen profiles will span bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic species. We encourage you to use Bug of the Month as a teaching tool to help educate health care personnel and start a dialogue about microbiology-related imperatives.

Find more Bug of the Month articles on www.infectioncontroltoday.com!

In the second part of our conversation with Danielle Rankin, PhD, MPH, CIC, epidemiologist with the CDC, she expanded on the infection prevention strategies and surveillance needs surrounding the rise of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (NDM-CRE). She is the lead author of a recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Rankin emphasized that early infection control measures are critical when a case is detected. “It’s really important that IPs work with their state and local health care-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance programs to prevent spread,” she said. Patients hospitalized with NDM-CRE should be placed on contact precautions, while long-term care residents require enhanced barrier precautions. She also underscored the basics: “Reinforce the importance of hand hygiene…before touching a patient, before performing an aseptic task, after contact with bodily fluids, and, of course, after glove removal.”

Environmental hygiene remains equally vital. High-touch surfaces, such as bed rails, call buttons, and light switches, should be disinfected regularly. Additionally, shared equipment like portable X-ray machines must be cleaned thoroughly between patients. “You also want to make sure that staff are not pouring patient waste down sink drains,” Rankin cautioned, citing sinks as a known environmental reservoir.

Hand hygiene options prompted a practical discussion. “Hand sanitizer should be used and can be used in all instances except if a provider’s hands are contaminated from blood or bodily fluids—then they need to actually perform hand washing,” Rankin explained.

Beyond daily practices, Rankin highlighted the importance of timely surveillance and mechanism-specific testing. “The primary need is to really obtain prompt mechanism testing for CRE so this information can be used for treatment selection,” she said. Yet she acknowledged barriers, including the lack of guaranteed reimbursement for clinical laboratories. Expanding testing capacity while maintaining strong public health laboratory support is essential for rapid response.

Her message for infection preventionists and epidemiologists was clear: “Historically, the most common carbapenemase was KPC [Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase], but now we’re seeing this surge of NDM-CRE in the United States, which really threatens to reverse years of stable or declining CRE rates.” With only 2 approved beta-lactam drugs effective against NDM-CRE, Rankin urged facilities to integrate mechanism testing into their workflows and use the CDC’s AR Lab Network when local resources are unavailable.

“Infection control interventions must be timely,” Rankin concluded, “to ensure patients receive appropriate therapy and facilities can prevent further spread.”

Read Rankin and her colleagues’ study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine here.

Find the first installment of the interview here.

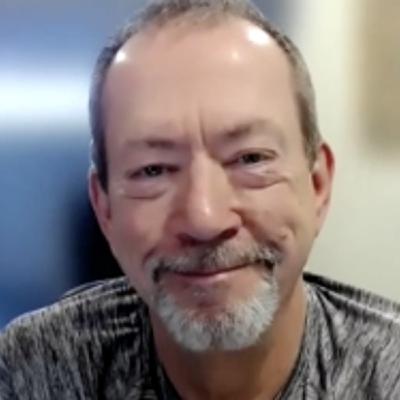

Amid the bustle of IDWeek in Atlanta, Georgia, held from October 19 to 22, 2025, former CDC director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, now president and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives, laid out a crisp playbook for infectious-disease professionals: a 3-step formula he says can prevent outbreaks, reverse drug resistance, and save “millions of lives.”

In a conversation with Infection Control Today, before the conference, Frieden previewed the themes of his new book, The Formula for Better Health: How to Save Millions of Lives, Including Your Own, and the talks he gave at the meeting. “I’ll be talking in a couple of presentations about a new approach,” he said. “It’s an approach that can prevent and stop outbreaks, that can prevent and reverse drug resistance, and that can save millions of lives. It is, ‘see, believe, create’—a 3-step formula for a healthier world.”

Step 1: See the Invisible

Frieden argues that public health’s “superpower” is the ability to detect what others miss and then turn those insights into action. “First, see the invisible,” he said. “See not just the numbers and drug resistance or things like the genomic epidemiology to understand the spread; see also the path to progress and see whether our programs are succeeding or failing. This is public health’s superpower.”

That vision, he added, requires nimble use of surveillance data, feedback loops that measure performance at the bedside, and the willingness to change tactics when results lag. It also means recognizing that many infections we accept as inevitable are, in fact, preventable.

Step 2: Believe Change Is Possible

The second step is psychological but no less essential. “Believe that we can change it. Believe the impossible,” Frieden said. “All too often, we assume that things are inevitable, when in fact, we can change them.”

That mindset shift is especially important for health care-associated infections (HAIs). “I’m confident that in 20, 30, 40 years, we will look back on the burden of hospital-associated infections in the US today and think, ‘How could they have let that happen?’” he said. “This is not a criticism of any 1 individual. We have great tools to have a better understanding to see the invisible, how infections are spreading in hospitals and other healthcare facilities.”

Step 3: Create a Disciplined, Organized Response

The third step turns belief into execution. “Work together to create a healthier future with organized, simple, well-communicated strategies that overcome the barriers to progress,” Frieden said. He pointed to practical elements that high-reliability organizations embrace checklists, empowered infection-prevention units that track and reduce infections, and clear communication with patients, frontline staff, and leadership. “Systematically overcoming the barriers…including inertia…is the path to lower infection rates,” he added.

A Lineage That Began in 1662

Frieden’s formula is anchored in history as much as modern analytics. “One thing that surprised me was that public health surveillance actually started in 1662, with a cloth merchant named John Grant,” he said, describing what is widely regarded as the first epidemiologic analysis of community health. Grant “described emerging diseases such as rickets” and even the economic implications of epidemics. Plague, Grant showed, sometimes killed most of a community, but other fevers were “more economically disruptive, because they caused so much illness that they were, as he put it, ‘scarce hands enough to bring in the harvest.’” For Frieden, the lesson is timeless: measure what matters, then act.

From Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis to Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales: Lessons Learned

Frieden’s stance is shaped by hard-won experience. “Over the past decades, I’ve worked on issues like multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, Ebola, the spread of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales and other resistant organisms,” he said. The through line: when leaders see clearly, believe improvement is possible, and create a disciplined plan, progress follows.

The 7-1-7 Target: “Find a Problem, Fix a Problem”

Frieden’s company, Resolve to Save Lives, has translated that mindset into a measurable target for outbreak detection and control. “The policy is 7-1-7—7 days to find every outbreak after it emerges, 1 day to report it to public health, and 7 days to have all essential control measures in place,” Frieden explained. “What we’re finding is that the 7-1-7 approach allows a ‘find a problem, fix a problem’ kind of worldview. Every single outbreak is an opportunity for continuous improvement with a simple yes/no—was it met or not? If not, not a blame to anyone—identify the bottlenecks and enablers and use that data to improve performance.”

What This Means for IPC Leaders

For infection preventionists, epidemiologists, environmental services leaders, sterile processing professionals, and infectious disease clinicians, Frieden’s message is both a challenge and a charge:

Make the invisible visible. Use surveillance, point-prevalence checks, and genomic/epidemiologic tools to map how infections move through your facility.

Set bold but concrete goals. Treat HAIs as unacceptable, and back that position with transparent metrics tied to accountability at every level.

Organize for reliability. Standardize with checklists, empower your infection prevention and control unit to drive change, and ensure leadership communication keeps momentum high.

Practice 7-1-7. Build the reflexes to detect, report, and control quickly—and debrief every event to get faster next time.

Frieden summed up the ethos in one sentence: “What we need to be doing in health care and public health is using data to improve performance, and that’s what ‘see, believe, create’ is all about—see the invisible trends, strengthen belief that we can change them, and then work together systematically to create a healthier future.”

For a field accustomed to complexity, the appeal is obvious: a simple, memorable framework grounded in evidence and experience that turns vision into action.

Join the Movement: Clean Hospitals Day is October 20, 2025

On October 20, hospitals around the world will pause to spotlight a truth we all know but rarely celebrate out loud: Environmental hygiene saves lives. Clean Hospitals Day 2025 is your chance to rally teams, thank the environmental services (EVS) professionals who keep care spaces safe, and set new habits that last long after the balloons come down.

Infection Control Today® (ICT®) spoke Alexandra Peters, PhD, CEO of Clean Hospitals and a member of ICT's Editorial Advisory Board. Speaking of environmental hygiene quality throughout the world, "If we raise the level everywhere, everyone wins."

Peters discusses how Clean Hospitals invites participation via email or its website: Hospitals can become members with access to think tanks and scientific sessions, while ethically aligned industry sponsors (capped at about 50 and evidence-driven) help fund the initiative. The coalition aims to raise environmental hygiene standards globally by breaking silos between academia, industry, and care delivery, and by collaborating with associations and ministries of health in symbiotic, nonmembership alignments (eg, sharing activities and materials).

Because pathogens ignore borders, the program stresses international cooperation—amplifying messages like Clean Hospitals Day—to protect patients, support health care workers, and lift practices everywhere.

“Clean Hospital Day is vital. EVS and their role in keeping patients safe are vital, and they deserve to be honored and recognized for their contribution to patient care,” said Brenna Doran, PhD, MA, ACC, CIC, another member of ICT’s Editorial Advisory Board. “And while they are the people behind the scenes who are making sure things are clean and trash is picked up, they are paramount in the ability of frontline staff to do the work that they do. We cannot function without EVS. And Clean Hospitals Day is our opportunity to really recognize and show the value and the impact that these amazing, hard-working, dedicated, passionate professionals have in our health care space.”

Why This Year Matters

This year’s theme, Human Factors & Collaboration, centers on the people behind safe care. It recognizes environmental services (EVS) teams as health care workers and calls on leaders to integrate EVS fully into interdisciplinary care: shared goals, shared data, shared wins.

Clean Hospitals is offering free, multilingual materials—posters, screensavers, social tiles, and talking points—so any facility, of any size and budget, can host a meaningful event.

A Simple Plan You Can Run With

1) Host a 60-minute kickoff huddle (Oct 20).

10 min — Welcome & purpose: “EVS is clinical safety.”

15 min — Micro-teach: human factors that help (clear workflows, stocked carts, good signage).

15 min — Barrier busting: quick roundtable on top two friction points; assign owners.

10 min — Recognition: shout-outs and “in-the-room” thank-yous.

10 min — Photo & pledge: team picture and a one-sentence commitment.

2) Lift up your experts.

Invite an EVS lead to co-present with infection prevention (IP). Make it crystal clear: Cleaning is care, and EVS are part of the clinical team.

3) Run a “See One, Fix One” sprint.

All week, encourage staff to report one barrier (empty dispenser, missing wipes, unclear IFU) and fix one they can resolve on the spot. Track quick wins on a whiteboard.

4) Measure something that matters.

Pick a fast, visible metric: percent of rooms with stocked hygiene supplies, percent of high-touch surfaces verified by fluorescent gel/marker, or time-to-isolation signage. Share before/after results at shift change.

5) Celebrate people, not just policies.

Hand out “I keep patients safe” buttons or badge tags.

Spotlight EVS pros on your intranet and digital boards.

Deliver coffee rounds to night shift.

Have senior leaders shadow a terminal clean.

Communication you can copy-paste

Talking point: “Environmental hygiene is a clinical intervention. When we clean well, we prevent infections, shorten stays, and protect staff and families.”

Pledge: “I will make the next patient’s room safer than I found it.”

Hashtags: #CleanHospitalsDay #EnvironmentalHygiene #EVSareHealthcare

Ideas for Every Department

Nursing: Standardize where wipes live, and who leads the room-ready check.

Facilities: Map ‘last 10 feet’ workflow so EVS carts, water, and waste routes reduce cross-traffic.

Supply Chain: Confirm uninterrupted stock for wipes, mops, and PPE; replace any “shared bottle” practices with single-patient items.

Quality/IP: Publish a one-page playbook for high-touch surfaces in your setting (ICU, OR, ED).

Leadership: Add EVS metrics to the safety dashboard and quarterly town hall.

Make It Last

Clean Hospitals Day is a launchpad, not a one-off. Convert your wins into standard work, schedule brief monthly barrier reviews, and keep recognizing catches. Small, reliable improvements at a massive scale beat rare heroics every time.

Call to Action:

Download the free Clean Hospitals Day 2025 toolkit (multilingual).

Listen to Clean Hospital’s Webber Teleclass Day

Put a 60-minute huddle on the October 20 schedule.

Choose 1 metric, 1 barrier, and 1 recognition—and make them visible.

Follow the Clean Hospitals LinkedIn page.

On October 20, let’s show patients—and one another—what safer care looks like: clean rooms, clear roles, proud teams. See you on #CleanHospitalsDay.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) carrying New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) are on the rise across the US, posing a growing challenge for hospitals, infection preventionists, and public health officials. In a recent interview, Danielle Rankin, PhD, MPH, CIC, an epidemiologist with the CDC, discussed her recently published study, which underscored the scale of the problem and the need for coordinated action.

“NDM is a type of carbapenemase, which is an enzyme that can inactivate carbapenems and other beta-lactam antibiotics,” Rankin explained. “Carbapenemase, like NDM, can share [its] genetic code with other bacteria, even if they were previously susceptible, rapidly spreading resistance.” Transmission most often occurs in health care settings, through direct contact, contaminated medical equipment, or environmental reservoirs such as sink drains and toilets.

CDC surveillance data revealed a dramatic rise in NDM-CRE. “Through the Antimicrobial Resistance Laboratory Network data, we recognized that NDM was actually increasing,” Rankin said. The CDC created a cohort of 29 states to analyze CRE isolates and track carbapenemase trends systematically. Results show NDM-CRE incidence has surged by more than 460%.

For clinicians, these shifts complicate empiric therapy. “There’s really not a one-size-fits-all approach,” Rankin noted. Facilities must foster close collaboration among microbiology labs, pharmacists, infectious disease specialists, and public health departments to adapt local guidelines.

Testing capacity also remains a bottleneck. Carbapenemase mechanism testing is often unavailable at the local level, leading to delays. “Clinical laboratories that perform inhouse testing have a marked advantage, with turnaround times around 6 days faster than public health labs,” she said. “By enhancing local testing capabilities, we can improve the timeliness of results and facilitate more effective and targeted patient care in the face of multidrug-resistant organisms.”

Infection preventionists must prepare for what Rankin described as a “poly-carbapenemase landscape,” where multiple resistance mechanisms, including OXA-48, may coexist. Vigilance is essential: “It’s important to remain suspicious if you’re seeing a rise in a single mechanism, even across different organisms.”

Environmental hygiene is another critical front. Rankin warned that sink biofilms can serve as hidden reservoirs: “If a faucet is directly over a sink drain, it can splash into that drain and then onto items around the sink,” enabling horizontal transmission to patients.

As NDM-CRE becomes more common, outbreak detection strategies must evolve beyond case-by-case responses. Whole genome sequencing and targeted screening of high-risk patients are among the tools CDC is piloting. “To prevent outbreaks,” Rankin emphasized, “facilities should continue monitoring hand hygiene, [personal protective equipment] use, and environmental cleaning and disinfection as well as sink hygiene.”

Read Rankin and her colleagues’ study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine here.

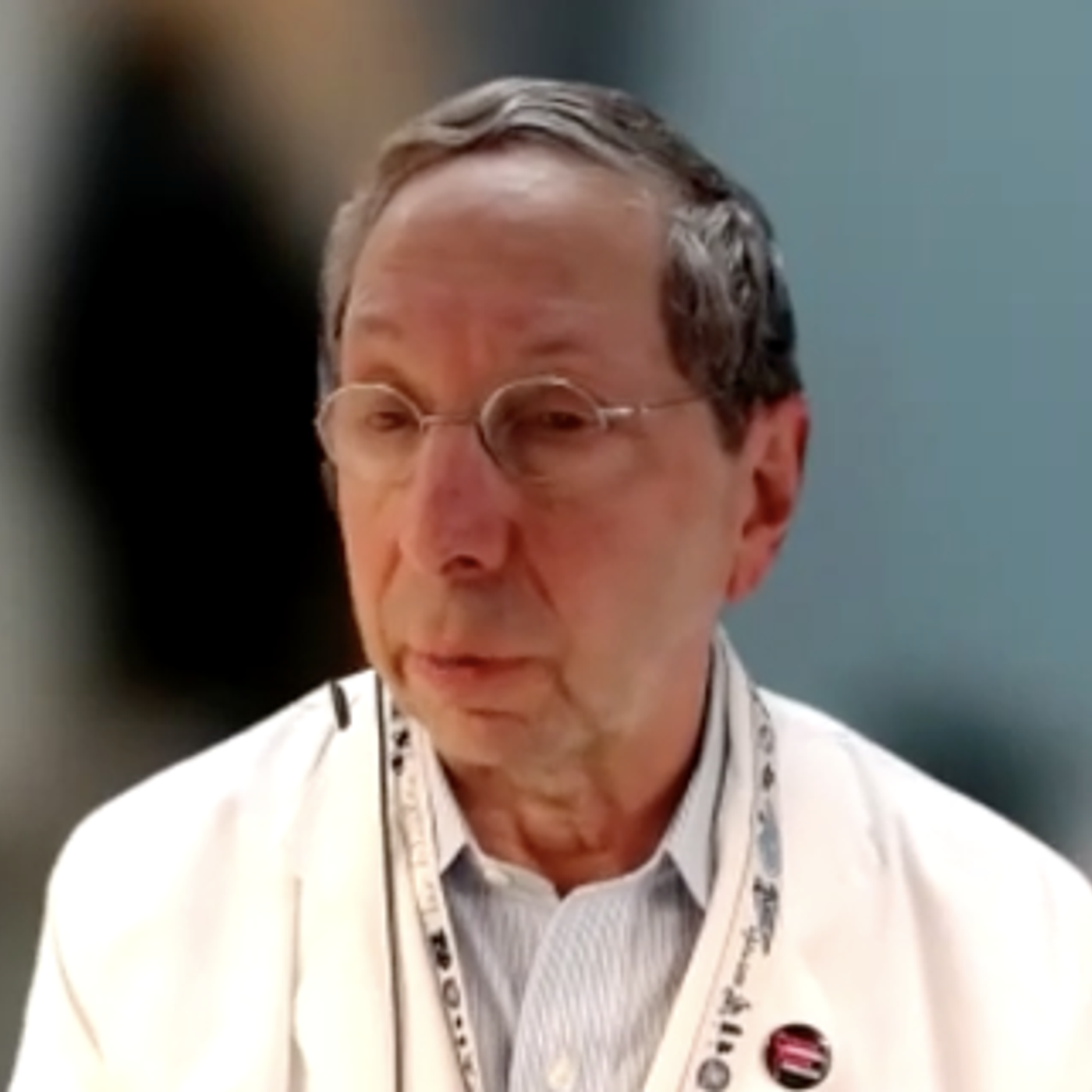

The sudden departure of the CDC director with several other top leaders has raised urgent questions about the stability of the nation’s leading public health agency and its ability to provide consistent, evidence-based guidance. In an interview with Infection Control Today®(ICT®), David J. Weber, MD, MPH, president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, and the medical director of the Department of Infection Prevention at UNC Medical Center, emphasized why strong leadership, scientific integrity, and prevention-focused strategies are essential for protecting both patients and communities.

“The Centers for Disease Control in the United States has been not only the leading public health agency within the United States, but look to worldwide,” Weber said. It “provides crucial guidelines for us in infection prevention, vaccines, but many other aspects of public health,” and serves as a vital conduit for federal support: “It serves as a pass-through for congressional funds…to state and local health departments to provide public health interventions.”

For Weber, the compass is clear: “We believe in public health guidelines should be evidence-based on peer-reviewed published literature.” The CDC’s surveillance role allows health systems to “direct the resources to the areas that are most impacted,” while transparent guidance spans prevention in hospitals and community vaccination. He underscored historic gains: “The two most important public health interventions in the last 150 years have been a safe drinking water supply and second, vaccines,” noting we have “eliminated smallpox… eradicated two of the three types of polio…and dramatically decreased…mumps, rubella, whooping cough, and…measles.” CDC laboratories also safeguard against the rare and the dangerous, from “human rabies” to “Ebola and Lassa.”

Selecting a new director demands depth and credibility. “That person should be a physician…[with] substantial experience in…public health,” and “enough of a scientific background…to follow the best evidence-based practice.”

Funding cuts, Weber warned, ripple locally. “Only about 5% or less is staff…but still, the majority of money is just a pass-through to state and local governments.” Proposed reductions “will…affect every person in the United States,” because they would “dramatically affect…city, county and state public health departments.”

At the bedside, fundamentals still save lives. “Proper hand hygiene before and after each patient in contact,” surface disinfection, and appropriate precautions are “the very basic things we do.” The economics align with the ethics: “For every dollar we spend on infection prevention, we save more money than we spend… Prevention is always better than treatment.”

The charge to clinicians is unambiguous: “We need to be the proponents for a safe and effective therapies…to counter both misinformation and disinformation.”

Infection prevention personnel are uniquely positioned to drive meaningful change in sharps safety, but only if we recognize and act on our critical role. Sharps injuries are not only a personal threat to health care workers; they also represent a preventable infection risk, a systems failure, and a missed opportunity for proactive intervention.

In the interview, available in its entirety here, with Amanda Heitman, BSN, RN, CNOR, perioperative educational consultant for Periop Anew and supervisor of education for surgical services at WakeMed in Cary, North Carolina, she discusses the issues and the need for education about sharps safety.

Despite the availability of engineering controls and regulatory guidance, facilities continue to face major barriers to ensuring sharps safety. It’s time for infection preventionists (IPs) to step forward as educators, advocates, and culture shifters.

One of the most persistent challenges is underreporting. Studies show that up to 50% of sharps injuries are never reported, often due to shame, fear of judgment, or a belief that the injury was the worker’s fault. This silence creates a dangerous illusion: facilities appear safer than they actually are. When leadership doesn’t see the problem, there’s little motivation to implement change. IPs can help break this cycle by fostering a non-punitive reporting culture, analyzing injury trends, and highlighting missed opportunities for safer practices.

Another common barrier is cost, particularly the perception that implementing safety-engineered devices is too expensive. However, IPs understand the true cost of an exposure event, including bloodborne pathogen testing, follow-up care, work restrictions, potential infections, legal liability, and staff burnout. These indirect and long-term costs far outweigh the price of a safety device. Infection prevention teams can use this data to build the business case for investment, linking worker safety to quality, staffing continuity, and even patient outcomes.

IPs are also well-positioned to advocate for safer technology. Passive safety devices, such as single-handed scalpel blade removers and retractable syringes, offer automatic protection with minimal user intervention, an essential feature in busy clinical environments. While active safety devices rely on the user to manually engage a safety feature (which often goes ignored), passive designs reduce error and boost compliance.

Yet many facilities still don’t require or consistently provide these devices. IPs can serve on product evaluation committees, recommend device trials, and push for adoption of OSHA-aligned engineering controls.

Education is another critical area where IPs can lead. Sharps safety training should not be treated as a one-time competency. New hires may arrive with outdated habits, and experienced staff may have learned shortcuts that increase risk. Ongoing training, especially hands-on demonstrations, is essential. IPs can support perioperative leaders, sterile processing educators, and unit-based champions in providing regular instruction on safe handling, passing techniques, neutral zones, and use of protective equipment.

Sterile processing professionals are especially vulnerable to downstream injuries when sharps are improperly handled in the operating room (OR). IPs can help bridge the gap between departments by reviewing root causes of injuries, updating workflows, and reinforcing the expectation that blades are removed using proper devices before instruments are sent for decontamination. This type of interdepartmental collaboration improves both staff safety and instrument turnaround times.

Ultimately, IPs are already experts in systems thinking, surveillance, policy development, and education—all skills that align perfectly with the needs of a comprehensive sharps safety program. By collaborating with clinical teams, championing device innovation, and advocating for a culture of safety, IPs can help ensure that no health care worker suffers a preventable sharps injury under their watch.

Infection prevention has always been about protecting others. It is time we extend that protection to the very people delivering care because sharps safety starts with us.

Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology’s (APIC’s) latest guide marks an important evolution in infection prevention by expanding beyond the traditional focus on central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSIs) to address all catheter-associated bloodstream infections (CABSIs). In this conversation with DJ Shannon, MPH, CIC, VA-BC, FAPIC, infection prevention manager and patient safety advocate for Community Health Network, a key contributor to the guide, Infection Control Today® (ICT®) explores why this broader approach matters, how it redefines patient safety priorities, and what infection preventionists (IPs) should take away as they work to reduce bacteremia risks across all vascular access devices.

The interview was conducted at the APIC Conference & Expo (APIC25), about the exciting news announced at the conference, held in Phoenix, Arizona, from June 16 to 18, 2025.

ICT: What was the final influence and inspiration to write this book?

DJS: Thankfully, I was approached by Becca [Rebecca Crapanzano-Sigafoos, DrPH, CIC, AL-CIP, FAPIC, executive director of APIC’s Center for Research, Practice, and Innovation] and Frankie [Frankie Catalfumo, MPH, CIC, CRCST, director of APIC’s Practice Guidance and Health Equity]. They had this idea—it's time. We needed to update our old CLABSI implementation guide, and they felt it was the right moment to bring a new face to it. Those of us on the writing and advisory teams realized we needed to broaden the scope beyond just CLABSI. From a patient’s perspective, they don’t care whether they develop bacteremia from a central line or a peripheral line—and neither do I. I want us to prevent all bacteremias. That’s really where this guide comes into play. We’re shifting from a framework hyper-focused on central lines and CLABSI to catheter-associated bloodstream infections—so all vascular access devices. I’m excited because it gives us a new way to share with infection preventionists and all healthcare workers how we can keep patients even safer.

ICT: In the book, the first part describes what a hospital-onset bacteremia (HOB), a CABSI, and a CLABSI are. Can you explain the differences and how they relate?

DJS: When we think about bacteremia, HOB stands for hospital-onset bacteremia and fungemia. That’s the big umbrella, capturing all bacteremias in patients, regardless of whether they’re linked to a medical device or a specific pathogen like MRSA. Then, under that, we have CABSI, which are bacteremias associated specifically with vascular access devices. And even more narrowly, we have CLABSI, which is just those bacteremias tied to central venous access devices or central lines. It all overlaps. We definitely discuss these distinctions in the guide and explain why this is a CABSI guide, not an HOB guide, right in the introduction. HOB is a huge topic with a lot of discussion right now, but we can’t boil the ocean overnight. This is one big step in the direction we ultimately want to go.

ICT: What do you want readers’ main takeaway to be once they finish the guide?

DJS: That’s a great question. At the center of our competency model is patient safety. Right now, by focusing mainly on CLABSI, we’re only looking at certain aspects of patient safety. Broadening our lens gives us a much bigger impact for patients—and that’s why we’re here. More tangibly, I hope readers realize the importance of infection preventionists collaborating closely with vascular access specialists. For example, literature might show that placing a device in a certain location reduces infection risk, and that’s statistically significant. But vascular access specialists focus on vessel health and preservation. There are so many more elements to device and site selection than what our usual infection prevention lens captures. I hope reading this peels back those layers and helps us learn there’s more to it than simply saying, “put this device in this location.”

ICT: Is there anything specific you want ICT’s audience to know?

DJS: Honestly, the whole guide—I’m a little biased—is valuable. But toward the end, we added a section on measures infection preventionists can bring into their facilities and surveillance programs. We all look at outcome measures like CAUTI and CLABSI, but we also outlined process measures. It’s not exhaustive, but it’s a solid starting point for thinking about what elements might be driving outcomes and what to monitor regarding the quality of care for vascular access devices.

ICT: Thank you for spending your time with me. It’s been so much fun to hear about this, and I can’t wait to see everyone’s reactions.

DJS: Thank you. It’s been wonderful, and I’m really excited about this guide. I hope everyone loves it too.

(Quotes have been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the video above for the entire conversation.)

As seasonal viruses surge and recent outbreaks like measles highlight vulnerabilities, infection prevention experts are extending their reach into schools, recognizing that healthy classrooms are essential to healthy communities.

Do you know not to wrap your lips around the suction tube the dentist puts in your mouth? You will when you finish this podcast.

Infectious diseases have long been a major concern for global health. While much attention is given to bacterial and viral infections, fungal diseases remain an underappreciated and growing threat. With limited treatment options and rising resistance to existing antifungal drugs, the world is facing a silent crisis that could have devastating consequences. David Angulo, MD, an infectious disease specialist and the president and CEO of SCYNEXIS, sheds light on the urgent need for new antifungal treatments and the challenges in combating fungal resistance in this interview with Infection Control Today® (ICT®).

Understanding the Scope of Fungal Infections

In this interview, Angulo explains that when most people think of fungal infections, they often imagine superficial conditions like toenail or yeast infections. While these are common and generally treatable, a far more dangerous category of fungal diseases exists—one that attacks the lungs, bloodstream, brain, and other vital organs. These invasive fungal infections are often life-threatening, with mortality rates ranging from 20% to 80%, particularly among immunocompromised individuals.

Angulo explains that patients undergoing chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients, and those in intensive care units are at the highest risk. In these situations, “You have multiple catheters placed in your body because of that reason, and then the fungi had the opportunity to get into your body and to cause these very severe infections,” Angulo said.

Angulo discusses the most common invasive fungal infections, which include:

Invasive Candidiasis: A bloodstream infection caused by Candida species, which can spread to organs and cause severe complications.

Aspergillosis: An infection caused by Aspergillus, a mold commonly found in the environment. It can destroy lung tissue and lead to fatal respiratory failure.

Mucormycosis: A rare but aggressive fungal infection with a mortality rate as high as 80%, affecting the sinuses, lungs, and brain.

Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever): A fungal pneumonia endemic to certain regions, such as the southwestern United States, that is expanding due to climate change.

Why Antifungal Resistance is a Growing Concern

The fight against fungal infections is growing more challenging because of rising antifungal resistance. In contrast to bacterial infections, which benefit from numerous groups of antibiotics, antifungal therapies consist of only three primary drug classes, as Angulo clarifies in the interview:

Polyenes (eg, Amphotericin B) – One of the first antifungal treatments, effective but highly toxic and limited to intravenous use.

Azoles (eg, Fluconazole, Voriconazole, Posaconazole) – The most commonly used antifungals, but resistance to azoles is growing at an alarming rate.

Echinocandins (eg, Caspofungin, Micafungin, Anidulafungin) – Newer antifungals with a better safety profile but limited to intravenous administration.

Angulo emphasizes the critical need for innovation: “Over the years, fungi have developed resistance against many of them, and at this point, that's really the biggest concern,” he said

His company, SCYNEXIS, is at the forefront of this fight, developing a new class of antifungal drugs called triterpenoids. "Our focus has been in trying to address the problem of antimicrobial resistance in the antifungal space, and really how to tackle those very difficult to treat diseases. That has been really the focus and the passion of this organization for the past 10 years," he explains.

As Angulo told ICT, "The antibacterial space was developed much earlier and faster, but right now, with a better understanding of the impact of fungal diseases and the development of resistance of fungal pathogens that has been evolving in the US, the CDC runs the primary surveillance program regarding the development of antimicrobial and antifungal resistance.”

By raising awareness and pushing for policy changes, the fight against deadly fungal infections remains a global priority.

Listen to ICT’s interview with Angulo to learn more about the history and treatment of fungal diseases.

The Textile Rental Services Association (TRSA) plays a vital role in supporting the health care industry and critical infrastructure by providing hygienically clean health care contact textiles (HCTs) and personal protective equipment (PPE). Representing a $50 billion industry with over 200,000 employees across 2,500 facilities, TRSA ensures that essential supplies, including isolation gowns, scrubs, bed linens, flame-resistant clothing, and safety items, are available to hospitals, first responders, laboratories, and food processing facilities. However, the US health care system relies heavily on disposable HCTs, leading to dangerous supply shortages during public health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Currently, over 90% of HCTs used in US health care settings are disposable, although reusable HCTs provide equivalent or even superior protection. The excessive use of disposable textiles threatens supply chain stability, making hospitals susceptible to disruptions due to global supply shortages, shipping delays, and manufacturing constraints. During the pandemic, the supply of disposable PPE, including isolation gowns, was significantly compromised, forcing hospitals to search for alternatives. TRSA members stepped in to fill the gap by supplying reusable, hygienically clean HCTs, ensuring that health care facilities could continue to operate safely.

“TRSA members process 90% of the HCTs (ie, isolation and barrier gowns, bed linens, scrubs, etc) used by health care facilities across the US,” TRSA’s press release read, “As evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, laundry processing interruptions threaten the safe operation of health care facilities as well as other critical infrastructure businesses.”

Reusable HCTs processed by TRSA’s Hygienically Clean-certified laundries offer multiple benefits, including:

Enhanced Safety: Reusable textiles meet rigorous cleanliness and sterility standards, ensuring they are contaminant-free after each use.

Supply Chain Security: Unlike disposables, which are often imported and subject to international supply chain disruptions, reusable HCTs are processed domestically, providing a more reliable solution.

Cost Savings: Long-term cost analyses show that reusables reduce overall expenses compared to continuously purchasing disposables.

Environmental Sustainability: Disposable PPE generates massive amounts of medical waste. Reusable alternatives significantly reduce waste and carbon emissions, aligning with green initiatives in health care.

Recognizing the need for supply chain resilience, a bipartisan congressional letter was sent in 2023 to then-Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Xavier Becerra, urging an investigation into the benefits of reusable HCTs. This led the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) to contract with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) to study the potential benefits of increasing reusable PPE adoption in health care.

In a 2-day NASEM workshop, technical experts, policymakers, health care providers, and industrial laundry operators evaluated reusable textiles’ safety, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability. The conclusion was clear: increasing reusable PPE use would significantly improve supply chain security, reduce waste, and lower costs. However, legislative action is required to drive widespread adoption.

TRSA’s Call to Action

Maryann D’Alessandro, director of the National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL), acknowledged the importance of reusable PPE but emphasized that the transition "is unlikely without legislation." She called for strategic partnerships to push for regulatory and legislative changes that support the increased use of reusable HCTs.

While long-term policy shifts take time, TRSA urges NIOSH to issue a “Workplace Solutions” document, which would serve as an interim step to promote reusable HCT adoption. Although it would not mandate enforcement, the document would raise awareness among health care facilities and provide guidance on integrating reusable PPE into daily operations.

The health care industry cannot afford another PPE crisis like the one experienced during COVID-19. Increasing the use of reusable HCTs is a proven solution for ensuring supply chain stability, cost savings, and environmental sustainability. TRSA remains committed to advocating for policies prioritizing reusable health care textiles, protecting frontline workers, and patient safety.

The conversation around reusable personal protective equipment (PPE) is gaining traction, especially in the wake of the pandemic-induced shortages. Infection Control Today’s interview with Joe Ricci, CEO of Textile Rental Services Association (TRSA), and Diane Troxel, MSN, RN, the director of clinical education at Handcraft Linen Services, shed light on the benefits and challenges of shifting toward reusable health care textiles. The experts cover key findings from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine workshop on reusable personal protective equipment (PPE), addressing misconceptions about reusable linens, and current state policy issues.

The Case for Reusable PPE

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted a workshop to examine the viability of reusable PPE. Findings revealed that reusable textiles offer significant advantages: lower costs, reduced environmental waste, and strengthened supply chain resilience. Unlike disposable PPE, which creates 15,000 tons of waste daily, reusable PPE can withstand up to 75 washes while maintaining its protective integrity.

“The reusable product, specifically reusable PPE in [a] health care environment, it reduced cost, it reduced waste, it improved supply chain resilience, and is a more environmentally sustainable product for the industry. Their ultimate outcome is to explore partnerships with organizations that can help increase the adoption of reusable healthcare PPE,” Ricci said.

Hospitals often hesitate to adopt reusable PPE due to concerns over cleanliness and storage logistics. However, commercial laundries follow rigorous hygienic standards, ensuring that reused PPE meets or exceeds safety requirements. TRSA’s Hygienically Clean Certification ensures that laundering processes eliminate bacteria and contaminants effectively, reinforcing confidence in reusable options.

Troxel said, “We have to convince the people [that the process is safe], and that's part of my job as the clinical educator. I go in and explain the process, invite them to our plant and tour, showcase that we are hygienically clean certified by TRSA, and explain that part of it to get them to understand.”

Barriers to Adoption

Despite the benefits, barriers to widespread implementation remain. Many healthcare facilities rely on disposable PPE due to habit, convenience, and purchasing structures tied to group purchasing organizations (GPOs). Decision-makers often view PPE as a disposable commodity rather than a service-based system, making the transition challenging.

Nurses and frontline workers must also feel comfortable using reusable PPE. Studies indicate that 60% of healthcare workers prefer cloth-based PPE over disposable alternatives due to comfort, durability, and perceived safety. Educating staff and administrators about the efficacy of reusable textiles is essential to shifting mindsets.

Legislation and Policy Initiatives

Ricci explained that several states, including New York and California, are considering mandates to require at least 50% reusable PPE usage in health care facilities. Europe’s health care sector has already embraced reusable textiles, experiencing fewer PPE shortages during the pandemic. The CDC and other federal agencies could play a pivotal role by recommending reusable PPE in health care guidelines.

“Europe had about 30% more reusable products than Canada, and they avoided shortages because they could rely on that rotating inventory. Since that inventory was available, production continued, allowing them to obtain that product and not [have the shortages we experienced.] They also consider the environment seriously. They are ahead of us on environmental issues, no doubt about it. Just look at their approach to the carbon tax and their efforts on extended producer responsibility and reducing single-use products. It makes a lot more sense to them than it does to us, but we're making progress. I think we're beginning to look at it more universally.”

Looking Ahead

The shift toward reusable PPE requires a cultural change, strategic investment, and industry-wide collaboration. As health care facilities prioritize sustainability and supply chain resilience, reusable PPE offers a proven, long-term solution.

Ricci said educating health care workers on the benefits of reusable linens is vital. “We're making an effort to sit down with the stakeholders in our industry, collaborate with them, communicate with them, educate them on the importance of the reusable product and what it does within our current healthcare environment and our changing health care environment.”

Troxel agreed and said, “It's about making sure that frontline staff have what they need for their best protection possible to keep patients safe.”

Join the TRSA 112th Annual Conference from May 13 to 15 in Greater Palm Springs. Find information here.

Resources for the video:

Here is a link to the National Academies’ proceedings: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/reusable-health-care-textiles-for-personal-protective-equipment-a-workshop

The NAS final report can be found here: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27762/reusable-health-care-textiles-for-use-in-personal-protective-equipment

Here is a link to the TRSA release, which includes a handy summary of the NAS findings: https://www.trsa.org/news/national-academies-workshop-validates-the-benefits-of-reusable-ppe/

Here is a link to the congressional letter requesting the NAS study: https://www.trsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Letter-to-HHS-Secretary-Becerra-Requst-Study-on-Reusable-Health-Care-Textiles.pdf

Here is some information on the site tour Ricci mentioned with the New York state assemblyperson: https://www.trsa.org/news/ny-state-assembly-member-engages-with-trsa-members-tours-unitex/

Here is a link to the New York state bill Ricci mentioned: https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S8169

Infection prevention has long focused on hand hygiene, but what about the surfaces patients and healthcare workers touch throughout the day? Jim Gauthier, MLT, CIC, alongside coauthors Carol Calabrese, RN, BS, CIC, and Peter Teska, MBA, introduced the concept of Targeted Moments of Environmental Disinfection (TMED)—a structured approach identifying 5 critical moments for cleaning high-touch surfaces in patient care areas, published in The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety.

In this interview, Gauthier discusses the importance of real-time disinfection, the hidden dangers of overlooked surfaces, and practical strategies to integrate TMED into daily health care practices, ultimately aiming to reduce health care-associated infections and enhance patient safety.

“TMED is a heuristic, risk-based model proposing additional cleaning and disinfecting within the patient zone modeled on a similar concept developed by [World Health Organization] for hand hygiene,” The authors wrote. “TMED identifies and suggests when disinfection should be conducted by [health care workers], either after or before certain procedures or events that may leave organisms on high-touch surfaces, or to remove organisms that may have been deposited during other care procedures.”

In an exclusive interview with Infection Control Today, Dr. Deborah Birx, MD, shared crucial updates on the ongoing threat of avian influenza (H5N1) and its implications for public health. With the H5N1 strain spreading globally and showing concerning cross-species transmission, Dr. Birx stressed the importance of strong infection prevention strategies, including improved surveillance, strict biosecurity measures, and cross-sector collaboration. She also highlighted the risks of viral mutations, the potential for human-to-human transmission, and the urgency of preparing healthcare systems for emerging threats. Her insights provide infection preventionists with actionable recommendations to tackle the evolving challenges posed by avian flu.