Discover The Wire Talks

The Wire Talks

The Wire Talks

Author: The Wire

Subscribed: 5Played: 11Subscribe

Share

© Copyright 2023 All rights reserved.

Description

The Wire Talks is back, but with a new look. Now, host Sidharth Bhatia will chat with guests on video as well as audio, on issues such as culture, politics, books and much more. Our guests will be well-informed domain experts. The idea is not to get crisp sound bites but to have a real discussion, resulting in an explanation that is insightful and offers the audience much to think about.

39 Episodes

Reverse

Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam have been in prison for the last five years. Their bail has been denied repeatedly. Last week their five colleagues, also arrested in the Delhi riot case of 2020, were granted bail. Why haven’t they?

Lawyer Sarim Naved, who fights both civil and criminal cases, analyses this in a podcast discussion with Sidharth Bhatia. While bail not jail is a general principle, “the courts have a lot of discretion in this matter”, he said. But he says, “the way the current government behaves, yes, a political element cannot be ruled out.”

Also, he says, times change and “our understanding of civil liberty shifts from time to time.” He points to cases from the 1990s when “somebody said Khalistan Zindabad and the Supreme Court said this does not amount to terrorism.”

But, he says that the cases of Khalid and Imam cannot be discussed by themselves without considering the larger systemic issues of police investigations and the judiciary. “Even in UAPA, there are people who are waiting for a longer period for their trials to start.”

The strong statements by President Trump against India are echoed by the growing anti-Indian sentiment in parts of the country. No longer are Indians viewed as the model minority — well educated, successful, tax-paying members of the US. Instead, they are rousing the anger of local communities. Some of the traits which are not very well liked, says journalist and author Salil Tripathi who lives in the US, “such as noisy celebrations, weddings, and you know, you take over the entire street and then after the after the wedding is over, you have a lot of garbage on the street or something like that. All of those things are attracting unwanted and untoward attention.”

He says the soft power of India is very much visible—Ravi Shankar was popular and now Yoga is, but such things are “a little more in your face.”

In Seema Says, this week, The Wire’s Editor, Seema Chishti discusses the reasons behind the United States’ attack on Venezuela and India’s muted response to the flagrant violation of international law. She also discusses how the strained ties between Bangladesh and India following India not allowing Bangladesh cricketer, Mustafizur Rehman for KKR in the IPL have got more strained. In a discussion with Elisha Vermani, Seema discusses the denial of bail to Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam and why everyone must go and watch the latest Hindi war film – Ikkis, based on a real life story.

Recommendations:

Seema:

1. Watch Varun Grover in Nothing Makes Sense - • Varun Grover || Comedy Special || Nothing ...

2. Neil Postman’s ‘Amusing Ourselves to Death’ / 74034.amusing_ourselves_to_death

Elisha:

On a woman rescued after two years of being locked up in a bathroom. https://www.himalmag.com/culture/dome...

Mumbai’s cuisine has been shaped by its migrants, not just from other parts of India but also from different countries.

“Irani food, for example, is not available in such abundance in other cities,” says Pronoti Datta, in this podcast conversation with Sidharth Bhatia. Datta’s new book In the Beginning There was Bombay Duck, a Food History of Mumbai, details the various cuisines brought by the city’s communities when they moved here. They brought their food traditions, met other food traditions and it all got transformed in the city.

“I suppose my one thought, one idea that runs through the book, or I hope it runs through the book, is the idea of what it means to be native. And the idea of you know, being native is a very strong political idea in the state” she says.

She explains that the dining out culture did not start in the then Bombay till quite late. Most eating places catered to the working classes of their particular communities—Maharashtrians, south Indians, Gujaratis, Muslims. Only the westernised restaurants, which became popular in the 1930s, were patronised by the elite. It was only the Irani restaurants that were open to all communities and classes, she points out.

Thirty years ago, Saeed Akhtar Mirza made his final feature film, Naseem, about an aging Urdu poet, played by Kaifi Azmi, and set in the days preceding the demolition of the Babri Masjid. The film opened with a title card which said, “That one act of demolition wrote the epitaph of an age that has passed, perhaps never to return!”

“The Babri Masjid epitomised the final collapse, you know, of an idea of India, of a sovereign, secular, democratic republic, equal for all, equality and justice. You saw it collapse in front of your eyes,” he said. “I was in despair but I was also angry when I made the film,” Mirza said in a podcast conversation with Sidharth Bhatia. He has not made any feature film since, though he still makes documentaries and has written two books.

Mirza spoke about how the “Hindu-Muslim binary was stupid” and said that those who promoted it hadn’t read any history. Their idea of history is “fundamentally flawed”, he said.

He said over 10 million young persons finished school every year and they too had aspiration. “They see glamorous weddings on television, they see cars, fashion and they want all that. And why not?” Without adequate jobs, “where will all that energy be channelled”, he asked.

He also spoke about the growing trend of Hindutva-oriented films and said that the filmmakers “know exactly what they are doing and in a strange way I believe they think they are doing no wrong because this is the time for retribution”.

But in the end, he said, “Hate cannot last forever, it has to have an expiry date.”

India’s left parties are no longer as influential as they used to be. In her new book, Comrades and Comebacks: The Battle of the Left to Win the Indian Mind, Saira Shah Halim, CPI(M) candidate in the 2024 elections, analyses the reasons for this and suggests the way forward.

“There have been strategic decisions that went wrong, but morally the Left has never made a mistake,” she said in a podcast conversation with Sidharth Bhatia.

Halim talks of the need to bring in the youth and look at contemporary issues – “Let’s look at gig workers, at student networks, at climate change movements, at women,” she said.

She felt that the BJP could not be taken on by showing "soft-Hindutva”. She believes Mamdani had shown radical ideas — “I mean, this guy is unfazed, he is taking on Donald Trump, he is taking on these right wing oligarchs, he is taking on these big capitalists, and he is winning because, you know, people are liking these new ideas, which are a far cry from the traditional morals of what the old communists stood for,” though she clarifies that the old guard was right in its own way.

Comedians and satirists have borne the brunt of the state and of people who are offended by something or the other, but even so, the stand up comedy scene is quite active with many faces. One such is Punit Pania, who left his corporate job 10 years ago and is now a very successful stand up comic.

His topics range from poor roads and civic architecture, know-all bhakt uncles, and NRIs, but he also talks about social issues. “In my first open mic, I had two minutes and talked about domestic violence because I felt it had to be talked about,” he said to Sidharth Bhatia in a podcast conversation. He noticed that a man from the audience left, “dragging a woman behind.”

Pania says he is not a political activist, but his comedy cannot help being political. “Why there are potholes on the road and why there is no beef on your plate, both things are politically driven. And those are just the most blatant examples. If you really drill down, almost every aspect of your life has a political background to it.”

Even so, he slips in references to political leaders. “When you completely inundate the country with your image and your persona and then people can't even mention your name. Even slightly critically. How is that fair? So, when you take all the credit you will get all the blame also.”

He also explains why the laws have made religion out of bounds but there are still “innovative ways to say what you want to say.”

Why have digital scams become so commonplace? And why are senior citizens falling prey to scamsters?

“We can say that a vast number of people who fall for cyber scams are senior citizens,” says Ruby Dhingra, a former journalist who co-founded Saksham Senior which works to digitally empowers senior citizens.

“There are a number of reasons for this, ranging from neurological factors and the fact that seniors have money in the bank, property etc.,” Dhingra said in a podcast conversation with Sidharth Bhatia.

She gives some examples of the kind of scams that are being perpetrated—from sextortion to investment opportunities to ‘digital arrest’ which has become very common. “A banker in Delhi lost Rs 23 crore to a digital arrest scam.”

“The digital arrest is the scariest,” she said. The victim is isolated from everyone and threatened with arrest if they step out of the house. “There have been cases where the victim is under digital arrest for a month.”

She said most scam organisations work out of South East Asia and the government brought back many hundreds of Indians last year who had been kept there forcefully.

It is no longer unusual to hear of someone, especially from a younger generation, who is undergoing therapy from a mental health professional, which is a big change from some years ago.

The Covid lockdown increased “stress, depression and anxiety for many” says Maherra Desai, clinical psychologist in Mumbai’s Jaslok Hospital on World Mental Health Day. “Social media too has increased a sense of isolation,” she says during a podcast discussion with Sidharth Bhatia. Desai explains there are many reasons why people seek out therapists — they may be in distress or feel they need help — “They recognise the need for mental health.”

She says not only do younger Indians seek out therapists for themselves, but also persuade their elders to do so too. “A de-stigmatisation has happened.” And queries come from all kinds of places. “I get messages from remote parts of the country from people who have found my number.” Many consult online too. “Online consultation too has taken off—earlier I was skeptical, but I now see it can be effective.”

India has a need but also a severe shortage of qualified counsellors. “The World Health Organisation recommends 3 psychiatrists per one lakh population, but India has only 0.75 per lakh.”

In President Trump’s second term, he has imposed several sanctions against India, starting from 50% tariffs on Indian exports for importing oil from Russia and the latest one of a massive $100,000 fee for new H1B applications. Considering that Indians get 70% of new H1B visas, it will affect professionals from India the most.

What is the reason behind these decisions, especially since many countries, including China, import oil from Russia? Does he have anything against India, more so since he calls Narendra Modi his friend?

“Trump is a bully and he likes strong leaders. ” says Manoj Joshi, Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation in this candid interview. Also, he says, “India does not offer the kind of business opportunities that China does.” As far as his praise for Pakistan, he has business opportunities with crypto deals there. “Plus, Pakistan. Nominated him for the Nobel Prize. He desperately wants it,” he said to Sidharth Bhatia on the podcast The Wire Talks.

He said the Indian side has chosen not to respond to Trump’s claims, “keeping a discreet silence.” “When we have no leverage, there is no point posturing.” Also, he said, “Indian leaders are not known for taking a courageous stand.”

Joshi also mentioned the huge fee on H1B visas, which, it has been clarified, are only for new applicants. “I don’t think H1B is a closed chapter.”

There has been growing anti-immigration and anti-Indian sentiment in many countries, including in Australia. A Member of Parliament recently claimed that the government was bringing in too many Indians so that they would vote for it.

The government criticised her and her own party demoted her status. A government report in 2021 called Indians a “national asset”. “The educated people and those in white collar jobs know this, but the rest of the populace does not,” says Surjeet Dhanji, an academic fellow at the Australia India Institute and a scholar of migration. “But when you have the Liberal party saying we need to cap migration or cap international students, and when Indians are among the leading numbers of migrants, what kind of message are you sending?”

The Indians are polite, they work hard, they pay taxes, they speak English, but “there are no Indians in leadership roles,” she said to Sidharth Bhatia in a podcast conversation. “We need a concerted effort by the Indian community to tell the layperson who watches the news or is on social media that Indians are contributing.” But Australians don’t like it when “migrants bring their home issues to this country.”

She explains that after the anti-Indian violence in 2008 and after Covid, migration slowed down and a huge backlog built up. “But the numbers of Indians are no more than of any other community,” she said. However, they are visible in many blue collar jobs such as couriers, hospitality, security guards.

The agitation in Nepal last week had three dimensions—the total collapse of the state machinery, multiple forces joining the GenZ agitators and unprecedented destruction of public and private property, says Mahendra P. Lama, senior professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi and an astute observer of Nepal for several decades. Lama was in Kathmandu during the agitation and also spoke to several local citizens.

“There was a huge gap between GenZ and the government,” he said in a podcast conversation with Sidharth Bhatia, ”but there was a pattern to the violence-it was well sequenced, with arson, looting, mayhem, killing.” He expressed surprise that the army was not summoned on the first day and the political parties remained quiet.

Over the past 10 years, there have been 14 prime ministers, some lasting barely three months and none of them had done anything for the country or its citizens. He said Nepalis were not violent people but the “Maoists had inculcated a culture of violence in the country.” He embossed that over this period, “India had nothing to bring stability to Nepal or help build institutions,” he said, adding, “India needs to change its strategy in Nepal.”

What is the cause of the severe flooding seen in northern states and cities?

“Climate change and its impact is intensifying rainfall pattern. The bigger failure is how our cities are designed, planned and managed and continue to grow,” says Mihir Bhatt, Ahmedabad based architect and urban planner. Bhatt is the director of the All India Disaster Management Institute, which works on initiatives in risk reduction and climate resilience.

He said there was a “design mismatch.” “Our stormwater systems and drainage networks are built for rainfall pattern for the past, not for the present, even less for the future,” he said to Sidharth Bhatia in a podcast conversation.

He also gave the example of Gurugram, where “rapid urbanisation filled in natural catchments that once absorbed excess water from the neighbouring area.”

Flooding would be seen in rural and urban areas for the near and perhaps long term future, but many solutions are there. He gave the example of Nagaland, where 39 local government bodies came together to work with the state government on disaster mitigation. “I am not a pessimist” he said. “Indians can build something if we let them.”

The reason why the Marathas have begun agitating for reservations in recent years is because there is a “rural as well as urban crisis” in the state’s political economy, says Sumeet Mhaskar, professor of sociology in OP Jindal University. Marathas are getting no access to economically secure jobs because more and more government jobs are contractual.

Mhaskar explains the process for getting reservations is not the Government Resolution (GR) such as the Maharashtra government has done. “Reservations can only be given by the Backward Caste Commission.” Nonetheless, he says, now the “OBC groups will agitate. They may go to court.” One danger for the OBCs is that the Marathas will stand for election in seats which are reserved for OBCs, he explains.

He also feels there is a political dimension to the entire agitation, especially since Fadnavis is a Brahmin and power traditionally has been held by Marathas. He points out that elections to municipal bodies are to be held soon and if Devendra Fadnavis hadn’t granted what the agitators wanted it would have had an impact on the elections.

A rupture has taken place within our community relationships and this will take a long time to heal even if the government changes. This is the candid analysis by Manoj Kumar Jha, academic and one of the more articulate Indian parliamentarians.

“Dogwhistling has moved from the fringe to the centre,” he says in a podcast conversation with Sidharth Bhatia.

Jha’s collection of columns has recently been published under the title In Praise of Coalition Politics and Other Essays on Indian Democracy. The essays cover a variety of subjects ranging from the caste census, Waqf properties, the RSS and government servants, and Jha’s letters to Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.

Jha says university appointments are made keeping in mind the candidate’s affiliation to the organisation. “The only thing spoken in favour of the new vice-president is that he is a die-hard RSS man. Is this a qualification for a post where the first one (vice-president) was Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan?”

Jha says, “If I love my nation, I must critique my government.” He points out that Nehru sat through debates where he was critiqued. “What is so sacrosanct today that you report from Assam and sedition laws are applied?”

Historian Richard M Eaton says he is “very concerned” at the erasure of the Mughals — “one of the most spectacular empires in the world” — from school history books.

Eaton, one of the most eminent historians of pre-modern Indian history, debunks some myths about the Mughals in this podcast conversation with Sidharth Bhatia.

He pointedly says that though the Mughals were Muslims, “they saw religion as a very personal affair and rarely tried to convert non-Muslims.” According to him, “they saw fooling around with religion as something that would only endanger the stability of the state. Akbar and Aurangzeb were both very explicit about not allowing religion to interfere with state policy.”

It was the British who painted the Mughal rule as a “dark period”, because that way they could “project themselves as bringing peace, stability, efficiency” to the land which had till then experienced incompetent rule.

He talks about how for a long time Aurangzeb was revered and venerated among his subjects, Muslims as well as well as Hindus. “His grave was a pilgrimage site,” he says. All this changed after the five volume biography of Jadunath Sarkar in the early 20th century.

Eaton makes it clear that this villainising Mughals will not change the basic fact that their influence on art, culture, good, language and everything else in India is all pervasive and part of India. “You will never get rid of the Mughals, you will have to live with them.”

There is a widespread belief that the 1950s were a time of great Hindi films, in terms of stories, songs and film-making. Seventy-five years later, fans still remember those songs, those stars and, most of all, those directors. We look back and call it the Golden age. What does that mean?

“I think it’s partly because the 1950s are also seen as a kind of Golden Age of India,” according to Rachel Dwyer, a former professor of film at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) who has written several books and articles on Hindi cinema. “A figure like Nehru at the time was seen as a major world figure. But also something exciting going on in Indian cinema at the time.”

“We saw several great directors working, the rise of major stars, playback singing being normalised and the stories too, which were usually about a hero looking to find a place in this new world, really spoke to people in a very direct way, and not just people in India, of course, but people across the world,” she said in a podcast discussion with Sidharth Bhatia.

Two of the major directors of the period were Guru Dutt and Raj Kapoor. This is the 100th birth anniversary of Guru Dutt and last year was Raj Kapoor’s birth centenary.

Dwyer discusses their work, through their films Pyaasa and Shri 420. “These have a great appeal about a certain innocence, about a freshness, and the way that they just happen to be really good entertaining films.” She also analyses their personas – the Raj Kapoor on-screen persona, the ordinary everyman, and Guru Dutt the poet.

The Election Commission’s announcement in Bihar that a citizen should prove his or her credentials to vote has sparked outrage among political parties. They say that a large number of marginalised communities will lose their right to vote.

“It is indeed very problematic. To shift the onus of establishing identity or citizenship on the voter is fraught on principle in a democratic country,” says Ashwani Kumar, senior advocate and a former minister for law and justice and also former Additional Solicitor General.

“What was the justification of excluding Aadhaar or ration cards from the process,” Kumar said in a podcast discussion with Sidharth Bhatia. He said that there is an element of distrust which has cropped up in the last couple of years. “So Election Commission now has the duty to dispel to the satisfaction of all concerned that its circular or its Special Intensive Revision (SIR) will not be exclusionary.”

He also spoke about declining standards of Indian democracy. “Political opposition in a democracy cannot be treated as personal enemies,” he said. “All parties, without exception, are being seduced by the temptation of using the harshest possible language against political opponents. That is what we have come to.”

The Devendra Fadnavis government has withdrawn its proposal to introduce Hindi in the early classes in schools in Maharashtra because of the opposition’s pressure. In Tamil Nadu too, there has been pushback on the introduction of Hindi by the Modi government.

“In Maharashtra the BJP cannot afford to take electoral risks,” says Professor Alok Rai, academic and author who has taught in universities in India and in the US and has written a book called Hindi Nationalism.

But, he points out, the BJP does not want just to introduce the language. “It has a larger cultural agenda behind it. Hindi carries within it a coded language,” he tells Sidharth Bhatia in this podcast. “The agenda is a Hindu agenda, an upper caste agenda.” The introduction of Hindi in the south “consolidates their support in the Hindi belt.”

Also, “School Hindi is very different from what is spoken on the streets,” he says. Everyday Hindi, that is Hindustani, "has evolved". “School Hindi is sterile”, he says.

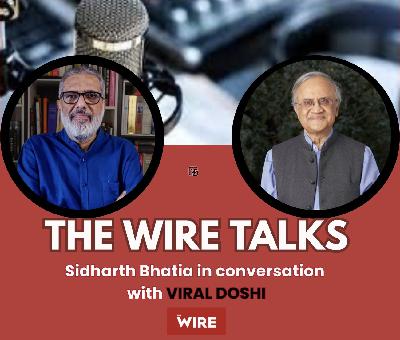

India sends students to the US in record numbers, but this academic year, applicants are feeling anxious before they head out. The changing policies of the Trump administration is likely to cause delays and tougher immigration questioning, among other things. Moreover, it is likely that the Optional Practical Training (OPT) programme, which allows F-1 visa holding students to work for a year or more, will be modified if not terminated. That was one of the great attractions for foreign students in the US. So is it still worth going to the US to study? “Absolutely,” says Viral Doshi, who has advised Indian students heading to the US for the last 20 years. “No other country can match up to the US,” he says, in sheer number of colleges, in the kinds of courses it offers and in the experiences one can have.

He acknowledges that parents have anxieties but “I tell them, have patience,” he says in a podcast discussion with Sidharth Bhatia. “Almost 50 percent students have already got visas and others will too, maybe a few weeks late for the first semester.” He says universities depend foreign students and are saying they will allow students to come late.”

“America is not the same as it was some years ago. Things have changed. No more internships and no more jobs or work experience.” And most important, he adds, “Avoid political activism.”