Discover FotogRAFia Podcast

FotogRAFia Podcast

FotogRAFia Podcast

Author: FotogRAFia Podcast

Subscribed: 2Played: 4Subscribe

Share

© Rafael Lopes

Description

Nifty voiceovers from the FotogRAFia Substack. Narrated by the writer, Rafael Lopes. It is strongly advised following along with the text for the photos!

www.cameraclara.com

www.cameraclara.com

18 Episodes

Reverse

In this live stream, I invited my friend Brian Chambers to walk us through the legendary Hasselblad V System. Brian brought his collection to the table and demonstrated why these 50-year-old cameras still captivate photographers today. We explored the remarkable modularity of the 500CM, witnessed the magic of mounting a modern 100-megapixel digital back onto vintage camera bodies, and got a peek at the panoramic X-Pan.Whether you’re curious about medium format film photography or considering entering the Hasselblad ecosystem, this conversation covers everything from mechanical engineering marvels to practical buying advice.Because I am a good person to you, I broke the video into chapters for your convenience, so you can jump to the area that most interest you, or just watch the whole thing, I guarantee you will learn something new.Please consider subscribing if you learned something from us today!Chapters00:40 Introduction & How We MetTwo camera nerds who bonded over film photography in NYC03:31 The Hasselblad 500CMFirst look at the V System and its waist-level viewfinder05:03 Taking the Camera ApartBrian starts disassembling to show the modularity05:48 Interchangeable Film BacksSwap film stocks mid-roll with the dark slide system08:42 Mirror Lock-Up for Long ExposuresHow to prevent mirror slap from affecting your shots12:47 The Leaf Shutter Lives in the LensWhy Hasselblad puts the shutter mechanism inside each lens14:14 One Crank Does EverythingThe elegant engineering of the film advance lever17:28 Multiple Film Backs in PracticeWhy professionals kept several backs loaded and ready20:19 The Red Flag SystemVisual indicators that prevent double exposures25:38 Lens Controls: Shutter Speed and ApertureHow the mechanical timing works on V System glass27:48 How Old Is This Camera?Brian’s 500CM dates to 197428:24 V System History and the H SystemFrom the 1950s mechanical cameras to modern electronic bodies30:33 Why Leaf Shutters Matter for FlashThe advantage of flash sync at any shutter speed34:15 The Problem with HSSWhy high-speed sync is a compromise, not a solution39:15 What Brian Loves About This SystemSharp lenses and the discipline of intentional shooting41:36 Tips for Buying Your First HasselbladThree things to look for when shopping47:41 The 907X Digital BackHasselblad’s 100-megapixel back that fits on 50-year-old bodies50:26 The Party Trick: Film Body Goes DigitalMounting the CFV 100C on the vintage 500CM54:28 100 Megapixels in ActionScreen share showing incredible detail from a studio portrait58:23 The Hasselblad X-PanA 35mm panoramic rangefinder co-developed with Fuji1:01:01 Reverse Film LoadingHow the X-Pan pre-spools so you never lose already-shot frames1:11:01 Adapting X-Pan Lenses to DigitalUsing vintage panoramic glass on modern Hasselblad bodies1:14:26 Final Advice for BeginnersBuild your kit piece by piece without breaking the bank1:16:06 Viewer Q&AA chat with a 500CM owner in the commentsWatch the Full StreamThe complete 1 hour 20 minute conversation is available above. Happy Thanksgiving to everyone celebrating!Liked the content? Consider sharing it to spread the knowledge! Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

Infrared photography reveals a hidden dimension of light invisible to human eyes. In this livestream, I sat down with photographer Michael Pacheco to explore what makes infrared such a compelling artistic tool, how the technology works, and the 12-year journey behind his personal project called Kindling for Reality.PS: Connect with Michael via his instagram or personal website.Michael brought camera equipment, a detailed slide deck explaining the electromagnetic spectrum, and years of hands-on experience shooting in infrared. You’ll discover technical foundations, but more importantly, you’ll encounter artistic experimentation, persistence, and the practice of seeing through a different lens (no pun intended!)Get comfortable, put some headphones, and watch the full 1-hour livestreaming. I’ve outlined the key chapters to guide you through the conversation, so you know what to expect.Camera Clara is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.Part 1: Understanding the electromagnetic spectrumTo shoot infrared, you first need to understand what you’re actually capturing. Michael begins by explaining how light exists across a spectrum of wavelengths. Visible light (everything humans can see) occupies only a small slice from 400 to 700 nanometers.Infrared light sits just beyond the red end of that spectrum, starting at 700 nanometers and extending to around 850 nanometers (what we call near-infrared). That’s the invisible heat you feel radiating from the sun, the same light your TV remote transmits.What’s fascinating is that birds can see ultraviolet light, which sits on the opposite end of the spectrum. This means flowers might appear entirely different to bees and birds than they do to us. They see patterns we’ll never perceive without specialized equipment. The same kinda applies to infrared photography. Your camera, when properly equipped, captures an invisible spectrum of light.Watch the video to see Michael’s visual explanation of the full spectrum and why this distinction matters for everything that follows.Part 2: How digital cameras block infraredEvery digital camera can technically sense infrared light. Your camera’s sensor is sensitive to wavelengths far beyond what your eyes can see. The problem is an infrared cut filter placed directly over the sensor. This glass barrier prevents infrared from interfering with normal photography, maintaining color accuracy and proper focus.Removing that filter is the foundation for infrared photography. Michael walks through this challenge in the video, showing an actual camera with the filter removed. He outlines two paths forward: expensive camera conversion with specialized companies, or the budget-friendly approach of using an external infrared filter on your lens.Part 3: Infrared filters and camera conversionAn infrared filter is essentially a dense piece of glass you screw onto your lens. It blocks all visible light while allowing infrared to pass through. Different filters pass different amounts of infrared wavelength, which affects the final look of your images.Michael brought a Sigma camera that has a removable IR cut filter, only sigmas SD and SD-H camera line can do this, so this specific camera doesn't need to be modified by Kolari Vision, he can take the filter out by hand and put it back anytime, which is wild, and the best of both worlds!The trade-off is significant: a converted camera becomes an infrared camera only. It can no longer shoot normal color photography (though conversion can be reversed by paying again). For dedicated infrared photographers, this sacrifice is worth it.Part 4: The "Wood Effect”The most striking characteristic of infrared photography is the Wood Effect, named after Robert Wood, the physicist who pioneered infrared photography in the early 1900s.In infrared photos, green vegetation reflects enormous amounts of infrared light, appearing bright white or yellow. Skies transform to deep blue or even black. Water takes on dramatic qualities. The result is a dreamlike landscape that feels alien compared to normal photography.The science is straightforward: chlorophyll interacts with infrared light completely differently than with visible light. The reflection is so intense that foliage practically glows in the captured image.Michael demonstrates this effect with examples from his personal work in the slideshow portion of the livestream. Watch to see how radically familiar scenes transform.Part 5: Experimental colorAfter years of developing his infrared technique, Michael spent a summer photographing the Azores, an archipelago known for dramatic volcanic landscapes. These images showcase infrared’s unique ability to capture lava rock and geological features.He describes beginning to develop presets for infrared photography, though he emphasizes the experimental nature of this work. Some color combinations look unusual or uncomfortable. That’s intentional. He’s exploring different interpretations of the infrared spectrum rather than chasing a single “correct” aesthetic.This is a fundamental insight: infrared photography rewards experimentation. There’s no single right way to process these images. Michael’s willingness to embrace failed tests and ugly mistakes is how artistic breakthroughs happen.In the video, he shares examples from this project and discusses his next directions, including portraiture in infrared, a technique he’s only recently begun exploring.Part 6: Infrared in cinema and fine artDuring the conversation, we discussed how filmmaker Denis Villeneuve used infrared photography for specific scenes in Dune. Those sequences capture the aesthetic power of infrared while telling a story. This is a reminder that infrared serves fine art and commercial filmmaking equally well.Kolari Vision has a very interesting post on How to Achieve the Infrared “Harkonnen Effect” in Dune: Part II – Kolari VisionI also referenced an Andy Warhol installation in Dia Beacon, that resembles some of Mike's infrared techniques, showing how this approach connects to art history and contemporary practice.These references matter because they position infrared outside the technical hobby space. It’s a serious artistic language with applications in cinema, gallery work, and editorial photography.Part 7: Why this work matters (and how to start)Michael concludes by reflecting on why he thinks this type of photography is valuable. Not everything needs to be immediately perfect. Experimental work is art. The point of pushing a medium to its limits isn’t to create flawless images every time. It’s to discover what becomes possible when you ignore convention.For photographers interested in starting their infrared journey, the barriers are lower than you might think. An external infrared filter costs under $100. A tripod and a clear day are the only other requirements.The hard part isn’t the equipment. It’s the patience to learn a different seeing. It’s standing in harsh midday sunlight (when most photographers stay inside), then looking at a familiar landscape and recognizing it could become something otherworldly.Infrared photography is powerful because it changes how you see.Further resourcesConnect with Michael Pacheco and explore his full portfolio through the links in this post. His Kindling for Reality project spans 12 years of infrared exploration. It’s a study in committing to a visual language and refining it over time.The full livestream runs approximately one hour and covers significantly more technical detail, personal anecdotes, and visual examples than this summary can capture. Press play above to watch the complete conversation. I hope you enjoy!Camera Clara is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

Note: This post derived from a live streaming. You can see the live streaming video by clicking above. I am providing both the live streaming and a long-form written text, so you can consume in the flavor you most like.On November 3, 2025, my wife ran the New York City Marathon. 59,226 runners took to the streets that morning, pushing through 26.2 miles across all five boroughs. Two million spectators lined the route, creating a human corridor of noise and support that could be heard blocks away.My son and I waited at mile eight in Brooklyn. He held a sign he’d made himself, his handwriting and an internal family joke (Emezinho Dentinho). I held my Voigtländer, a film camera that requires manual winding after each frame. My friend Brian stood beside us with his Leica Monochrome, camera set to burst mode.We tracked her on the marathon app. The crowd around us swelled with other families, other signs, other cameras. For fifteen minutes, we watched strangers run past, each one searching the sidelines for familiar faces.Then she appeared.Brian’s camera captured what happened next in a sequence of frames, each one separated by fractions of a second. But one photograph stands above the rest. In it, you can see a true exhibition of studium and punctum.Understanding studium and punctum in photographyRoland Barthes published Camera Lucida - Reflections on Photography in 1980, just months before his death. The book explores photography through two concepts: studium and punctum.Studium refers to the cultural and contextual elements of a photograph. It’s what the image documents and communicates. When you look at a photograph and understand the setting, the circumstances, the technical choices, you’re engaging with its studium. It’s the education the photograph provides, the story it tells through visible facts.Punctum is different. It pierces. The Latin word means “wound” or “mark left by a pointed instrument.” Barthes describes it as the detail that shoots out from the photograph like an arrow. You can’t always name it. It touches something deeper than cultural understanding. It’s personal, emotional, sometimes unexpected.Great photographs contain both, like the photograph from mile eight contains both, in extraordinary measure.The studium in this shotBrian chose 1/125th of a second for his shutter speed. This decision matters. At 1/250th or faster, he would have frozen the background runners completely. The photograph would lose its sense of motion. At 1/60th or slower, we would have been blurred too, our frozen moment lost to the flow of time.Instead, 1/125th creates perfect motion separation. The runners behind us blur into streaks of motion. The world races past. But my family stands sharp and clear, suspended in our own timeline. We are delaying the racer. We are stealing twenty seconds from her marathon for ourselves.Brian set his aperture to f/16. The background runners remain visible despite the motion blur. You can see the crowd, the urban landscape of Brooklyn, the scale of the event. The ISO sat at 4000, which the Leica Monochrome handles without visible degradation.But look closer at the content itself.There’s her face as she sees us. The joy of recognition after running eight miles. Her wedding ring visible on her hand reaching toward our son. The AirPods in her ears. The race bib pinned to her chest.There’s my son with the sign he created. His perfect small hands gripping the white board. His headphones protecting his ears from the cowbells and air horns. The toys attached to his backpack. Everything that makes him himself.There’s me with my camera, doing what I always do for my family. Photographing. Documenting. Creating the archive of our lives together. The Voigtlander at my eye, the winder trigger in my hand.There’s the “emezhino” reference on the sign, an inside joke from our family that no one else would understand.And there, in the middle background, perfectly placed, another runner races past. The marathon continues. Time moves forward for everyone except us.This is studium. The photograph tells you where this happened, when it happened, why it matters. It documents a specific moment in a specific place with specific people. You can read the photograph. You can understand it.The punctum. What pierced me.Here’s what makes me cry when I look at this photograph.It’s my wife’s face. The exact expression as she recognizes her family on the sidelines. That specific smile. The way her eyes find our son. The happiness of this connection in the middle of her hardest physical challenge.That’s my punctum right there.I didn’t see it when Brian was shooting. I was busy with my own camera, trying to capture the moment on film. Brian’s digital burst mode was capturing frames I wasn’t aware of. Later, looking through the sequence, this frame stopped me.The punctum cannot be forced. Barthes says that if the photographer’s intention becomes too obvious, if the detail is deliberately staged, it loses its power to pierce. What I can name cannot really prick me, he wrote. The punctum in this show works because Brian captured something genuine. He didn’t stage anything. She wasn’t performing for the camera. She was living through a real moment, and the photograph preserved something ineffable about it.Your punctum might be different from mine. Perhaps you notice the contrast between my son’s small hands and the adult world of marathon runners. Perhaps the wedding ring catches your attention. Perhaps it’s the runner blurred in the background, unknowingly becoming part of our family story.Barthes believed that punctum arrives through details the photographer doesn’t fully control. The photograph captures more than the photographer intends. Something in the frame pierces the viewer later, sometimes long after the image was made.Film emulation with DxO FilmPack 8The photograph came from Brian’s Leica Monochrome. I exported it as a TIFF file and opened it in DxO FilmPack 8. The software offers numerous film simulations, but I chose Kodak Tri-X, which made a great emulation job.The grain structure simulation is also very precise, with random grain, and adjustable knobs to select grain size, type, and intensity.Tri-X carries specific associations for photographers. It’s the film of photojournalism, of street photography, of documentary work. The grain structure, the contrast curve, the way it renders tonality: these characteristics evoke a particular aesthetic tradition, and DxO FilmPack 8 emulated it with perfection.Note: DxO kindly shared a 15% discount code for Camera Clara readers who would like to explore FilmPack 8, use the code RAF15.PrintingPrinting came next. I use a Canon image PROGRAF PRO-300. The printer uses ten inks, with three dedicated specifically to black tones. For monochrome prints, this matters enormously. The tonal gradation from pure black through mid-grays to white requires subtle ink mixing.The paper was Canon’s Premium Fine Art Smooth. A3+ size with 25mm margins. The printer takes approximately five minutes for a print this large at this quality. The ink saturation is substantial. After the print emerges, I let it rest for forty seconds before handling it.The physical print reveals details the screen obscures. The grain becomes tactile. The tonal relationships shift. There’s a permanence to the print that the digital file doesn’t possess, and I am now happy this moment will be hanging on my living room’s wall. Thank you, Brian!Camera Clara is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

My proven Negative Lab Pro workflow for scanning film negatives. Convert RAW files to stunning positives with proper color matching, presets, and efficiency. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

Thank you to everyone who tuned into my live video! Join me for my next live video in the app. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

Converting a medium format (6x7) with Negative Lab Pro. The film is a CineStill 400D. Hope you like it! Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

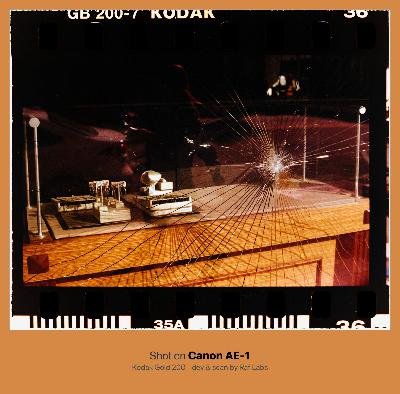

In this blogcast episode, Colin Czerwinski and I discuss a collaborative photography project, focusing on the magic of Kodak Gold, to photograph old cars, and abandoned towns. Our conversation highlights the beauty of everyday life through the lens of film, emphasizing the textures, colors, and stories that emerge from our photographic work.Together, we selected the best shots from the three rolls I sent him and discussed some curiosities and thoughts that crossed his mind while shooting. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

How I transformed the slow, often tedious process of film scanning into an efficient and enjoyable workflow. Inspired by Henry Ford’s principles of industrial efficiency, I optimized my scanning setup using batch processing, automation, and a Stream Deck to streamline repetitive tasks. By scanning in batches and editing entire rolls together, I achieve more consistent results while making the process faster and less frustrating. Switching from SilverFast’s unreliable color grading to Negative Lab Pro gave me more control, allowing for flexible edits without rescanning. Ultimately, my home setup now operates like a mini-lab, turning what once felt like a chore into a refined, structured part of my creative process. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

Summary:After carefully shooting and developing three rolls of film from a special trip to Brazil, I discovered they were completely blank. The culprit? An exhausted developer that failed just before reaching its advertised limit. This loss was devastating—not just because of the images, but because of the effort and meaning behind them.Yet, this is what makes film photography so brutal and so rewarding. Unlike digital, where everything works by default, in film, chaos is the default. Every successful frame is proof of skill, patience, and mastery. This failure is a reminder that resiliency is essential—not just in shooting, but in every step of the process.But I refuse to be defeated. This won’t stop me. Tomorrow, I’m buying fresh chemicals and developing five more rolls. Because film photography demands strength—and I am strong. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

On a rare sunny winter day in New York City, I embarked on a long-anticipated bike ride to the George Washington Bridge, armed with my Voigtländer camera and two distinct film stocks—Kodak Ektar 100, known for its rich, warm tones, and SantaColor 100, a repurposed Kodak Aero film designed for aerial reconnaissance and clarity over aesthetics. The journey, filled with breathtaking contrasts of snow and steel, was a testament to endurance and adaptation. Along the way, I captured cityscapes from a ferry, navigated freezing paths, and relished a warm meal in the Bronx—only to face an unexpected setback when my vintage Leica Summicron 50mm lens slipped from my numbed fingers onto the cold asphalt. The frustration of that moment forced me to reconsider my approach to gear, leading me to invest in the rugged, weatherproof Canon Sure Shot WP-1, a smarter companion for my cycling adventures. This ride reinforced a lesson in photography and life: creativity thrives on resilience, and the right tools can shape the experience as much as the images themselves. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

Most 35mm film scanners crop out film borders, removing sprocket holes and text markings that prove an image was shot on film. This post explores why film borders matter, from preserving composition integrity (as Henri Cartier-Bresson emphasized) to acting as a certificate of authenticity for analog photography.While some photographers see borders as unnecessary, others value them for their aesthetic appeal and proof of unaltered composition. The post also calls for scanner manufacturers to offer an option to preserve film edges. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

Developing my first ten rolls of film revealed ten key insights: understanding the deeper “why,” feeling the therapeutic rhythm of the darkroom, chasing consistency, embracing surprise color casts, shooting more deliberately, savoring the slow scan process, welcoming the wait, working with ISO limitations, celebrating a warm, supportive community, and finally, inviting others to experience the magic. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

A deep dive into the magic of CineStill 800T and why it thrives in neon-lit environments like Times Square. From the film’s tungsten balance to its signature halation, I explore how it transforms the urban nightscape into a cinematic dream. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

When the snowstorm hit, I couldn’t resist the urge to go out and capture it. While others stayed warm indoors, I braved the cold with my CineStill 800T, juggling an umbrella, a manual-focus lens, and the ever-present risk of moisture damaging my camera. My destination? Basile’s Pizza—the shot I knew would be the best of the night. Battling wind, snow, and fogged-up gear, I pushed through, improvising as I went. By the time I reached my refuge, all I could think about was drying my camera with napkins. The adventure was exhausting, but the story and the photos made it all worth it. And yes, I’d do it all again—before the snow melts. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

A long-awaited Leica camera arrives, craving light but lifeless without a CR123A battery. With urgency, the missing heartbeat is found, and something shifts as the red dot flickers to life. The camera doesn’t just work—it speaks, and has feelings! Loaded with CineStill 800T, it pulls its photographer into a neon-drenched world, firing instinctively, guiding each frame like it has a will of its own. The shutter becomes a whisper, the flash an unexpected command. By the end of the night, they are no longer photographer and tool, but partners in a cinematic dream. The Minilux isn’t just alive—it’s in love. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

(Check Substack for original text and photos on https://blog.rafalop.es) -- This episode explores the journey of developing 35mm film at home, framed by Walter White’s quote on chemistry as change. We discuss the thrill of managing the entire process—from mixing chemicals to revealing hidden images—and highlight the challenges of temperature control and reel loading. The conversation covers why labs still matter, but also how hands-on experimentation fosters resiliency and a deeper bond with analog photography. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

This episode recounts a once-simple plan—driving to Princeton on a winter day to shoot film—that unexpectedly turned into a night of flat tires, thick snowfall, and impromptu photography adventures. You’ll hear about the roadside mishap that forced an overnight stay, the tense drive through whiteout conditions, and the late-night snapshots that captured gas stations in swirling snow. It’s a reflection on embracing the unplanned, the kindness of strangers, and the magic of film photography under neon lights—and we invite you to settle in, listen, and discover how a bit of adversity transformed an ordinary trip into a compelling story. Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe

The Start of My Film Journey“From the first roll, I was hooked.”Photography has always been a part of my life. As someone born in 1986 and growing up alongside the evolution of digital photography, I’ve always been drawn to its precision, immediacy, and control. High-resolution sensors, advanced autofocus, and powerful editing tools like Lightroom have been my companions for years.Even in film photography, digital technology often plays a pivotal role. Scanning film with a digital camera and a macro lens, for instance, can create sharper, more detailed images than traditional scanners. It’s a testament to how far digital tools have come. But even with all this power at my fingertips, I found myself craving something more.When my mother brought me old family negatives last Christmas, along with a Nikon L35AF camera, I decided to give film photography a try. From the first roll, I was hooked. Loading the film, carefully setting the ASA, and advancing the frame felt like a conversation with the past. It was as though I was connecting with the same photographic journey my parents and grandparents once took, but on my own terms.Fotografia is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.Why Film is Different“The film camera communicates authenticity and hobbyism, which makes street photography more efficient and genuine.”The limitations of film didn’t hinder me. They inspired me.This process reminds me of playing a vintage bass guitar. Modern guitars are often manufactured with CNC machines, capable of cutting wood with extreme precision. They produce instruments that are flawless in their construction and reliability. But a vintage bass, with its handmade imperfections, worn-in frets, and history in its wood, creates a different kind of connection. It’s not just about the sound: it’s about how holding that instrument makes me feel. It inspires me, sparking creativity in ways a modern machine-made bass never could.Film cameras feel the same way. The mechanical precision of advancing film, the resistance of manual focus, and the sound of the shutter are all part of an immersive experience. With each frame, I’m not just capturing an image, I’m engaging with light, shadows, and composition in a way that feels deliberate. Every click matters because every frame costs something.When talking about street photography and riskier shots, I must also note how using a film camera positively influences the way people perceive you during street photography. There’s something disarming about seeing someone advancing film and practicing slow photography, it immediately conveys that you’re an enthusiast, not a private detective or someone with ill intent.This dynamic shifts interactions significantly. People react better, often intrigued by the process rather than wary. It aligns with the concept from Marshall McLuhan’s book The Medium is the Massage, where the medium itself shapes the message being received.The film camera communicates authenticity and hobbyism, which makes street photography more efficient and genuine. Moreover, there’s a unique safeguard when using film. If someone, like a security guard, demands that you delete a photo, the absence of a delete button means your property (the roll of film) remains intact unless someone physically removes it. While losing a roll in extreme cases might be a frustrating compromise, it keeps interactions civil and avoids unnecessary escalation.The Unexpected Joy of Community“Film photography has a unique way of bringing people together.”But what surprised me most about film photography wasn’t just the process or the results: it was the community.I experienced this firsthand when I met Nicholas Lopresti. He became a guide in my early days of home development, helping me navigate the complex world of chemicals, timings, and tools. Without his help, I doubt I would’ve had the confidence to develop my first roll successfully. Moments like this remind me that photography isn’t just about the images we create, it’s about the connections we make along the way. If you benefited from his tips, or just laugh with his videos, consider going to his Shop and supporting his job, as the world needs more creators like him.Film photography has a unique way of bringing people together. Whether it’s online forums, local meetups, or the friendly staff at labs, the community is incredibly welcoming. Many photographers are eager to share their knowledge, whether it’s about camera mechanics, film stocks, or developing techniques.The Time Spent Reflecting on My Creations“Each photo carries a story.”The scanning process has also been unexpectedly transformative. Each scan takes around 3–5 minutes per photo, which forces me to slow down and really look at my work. I notice the details, the play of light, the textures, the small imperfections, and reflect on what I could improve. This time spent with my images has sharpened my critical eye and deepened my appreciation for the art of photography.Recently, I scanned over 500 35mm negatives from my family archive, images that are over 30 years old. Seeing these moments preserved in vivid 65-megapixel TIFF files is a powerful experience. Each photo carries a story, a memory, and now a level of detail that ensures it can be cherished for years to come.Lessons Learned / Key TakeawaysFilm photography has taught me so much more than just how to shoot on film. It’s taught me patience, resilience, intentionality, and how to truly see. It’s connected me to a community of people who share that passion. And it’s reminded me that the most meaningful parts of photography aren’t just the images, it’s the journey of creating them. And mostly important: I made new friends.Here are some photographies I did with my new Voigtländer Bessa R2A and the old Nikon L35AF, some of them developed and scanned by Gelatin Labs, some other I developed and scanned myself. Please consume them slowly, allow you some time to think about details, I urge you to not scroll like we all do on Instagram.Expect more film photography around here! Get full access to Camera Clara at www.cameraclara.com/subscribe