Discover Turan Tales

Turan Tales

Turan Tales

Author: Agnieszka Pikulicka

Subscribed: 14Played: 135Subscribe

Share

© Turan Tales

Description

Turan Tales is a weekly podcast covering underreported stories of people, politics and social change in Central Asia by journalist and author Agnieszka Pikulicka

turantales.substack.com

turantales.substack.com

36 Episodes

Reverse

This week, we talk about carpets in Central Asia: their history, the differences between various carpet-weaving styles, the roles carpets played in different communities, and how the Soviet Union hijacked the practice of carpet making and transformed it to serve its own purposes.Joining us is Anushe Dust, a Tajik-born founder and editor-in-chief of RugMag magazine, where she uncovers the stories, memories, and secrets woven into carpets from around the world. She’s also a film critic and the curator of Carpets in Films, an ongoing archive of carpets in movies. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week, we’re taking a closer look at the Tajik-Afghan border. In the recent months, the area appeared in the media in the context of shootings and armed clashes that costed the lives of at least ten people, according to the AFP.What do recent incidents reveal about security along the Tajik–Afghan border? And how have the relations between Tajikistan and Afghanistan evolved? To answer these questions, we trace the relationship back to the 1990s and the US invasion of Afghanistan.Joining us is Mélanie Sadozaï, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Regensburg in Germany whose work focuses on cross‑border relations between Central Asia and Afghanistan, in particular the Pamir region. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week is about change - and the lack thereof. We will be looking at Uzbekistan: how the country was shaped during the post-Soviet period under the regime of Islam Karimov, and what has changed since Shavkat Mirziyoyev came to power. How different is the “New Uzbekistan” from the Karimov era?Joining us is Joanna Lillis, a Kazakhstan-based journalist and the author of Silk Mirage: Through the Looking Glass in Uzbekistan, published last November. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Welcome to the first episode of Turan Tales in 2026! We'll look at the fascinating story of oil and gas in Kazakhstan: the history of the industry, corruption scandals, the environmental damage it likely causes and much more.Joining us is Paolo Sorbello a journalist and researcher based in Almaty, Kazakhstan. He is the English language editor at independent news outlet Vlast.kz where he also hosts Dapter, a podcast about research in Central Asia.Paolo holds a PhD from the University of Glasgow, where he researched Kazakhstan’s oil sector. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Over the past few months, Central Asia has witnessed a series of significant developments in the art world, from the opening of the Almaty Museum of Arts, the largest modern art museum in the region, to the launch of the first-ever Bukhara Biennale.As new institutions, exhibitions, and art spaces continue to emerge across the region, a larger question arises: Can modern art flourish in Central Asia?To find out, we’re joined by Timur Karpov, a documentary photographer and cultural entrepreneur from Uzbekistan, and the founder of the 139 Documentary Centre. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

On November 30th, Kyrgyzstan went to the polls to elect a new parliament - the first since Sadyr Japarov became president in 2021 following a revolution just a few months earlier. How exactly has Kyrgyzstan changed under Japarov, who has ruled in tandem with the powerful head of the security services, Kamchybek Tashiev? And what should we know about the latest election?To find out, I spoke to Asel Doolotkeldieva, a research fellow at the University of Potsdam, a critical political scientist and political sociologist who has widely published on Kyrgyzstan’s revolutionary politics and the populist turn of October 2020. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week we're joined by Diora Rafieva, an Uzbekistani lawyer and human rights activist who has been at the frontline of the fight to save Samarkand and its architectural and social heritage from the ongoing demolitions - and bad taste. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

They came to Russia for work, not war. Yet thousands of Central Asian migrants now fight in Ukraine - drawn in by promises, pushed by pressure, and caught in a stark imbalance of power.This story is part of our new series of audio features - also available as long reads - made possible by the International Press Institute. If you enjoy it, leave us a comment or reply to this email with your feedback — we’d love to hear what you think. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

In this week's episode, we'll try to answer the question of whether Turkmenistan is on the path to reform. Joining us is Ruslan Myatiev, a Turkmen journalist, and the founder and editor of Turkmen.news - an independent media and human rights organisation based in the Netherlands that focuses on Turkmenistan. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week on TURAN TALK we trace the history of US relations with Central Asia through the experiences of Daniel Rosenblum - a former US ambassador to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and a long-time expert on the region. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week, we’re looking into a fascinating and often misunderstood topic: witchcraft, clairvoyance, fortune telling, and other spiritual practices popular in Tajikistan and the rest of Central Asia.Joining us is Dr Anna Cieślewska, a social anthropologist and orientalist at the Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Łódź in Poland. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week, we’re talking about uyat and Central Asia’s culture of shame. Joining us is Dr. Hélène Thibault, Associate Professor of Political Science at Nazarbayev University in Astana. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Astana has risen from the steppe as a city of glass, steel, and soaring ambition - a capital built to embody a nation’s dreams. But can a dream live up to its promise?Support Turan Tales with a paid subscription at: turantales.substack.com/subscribe Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

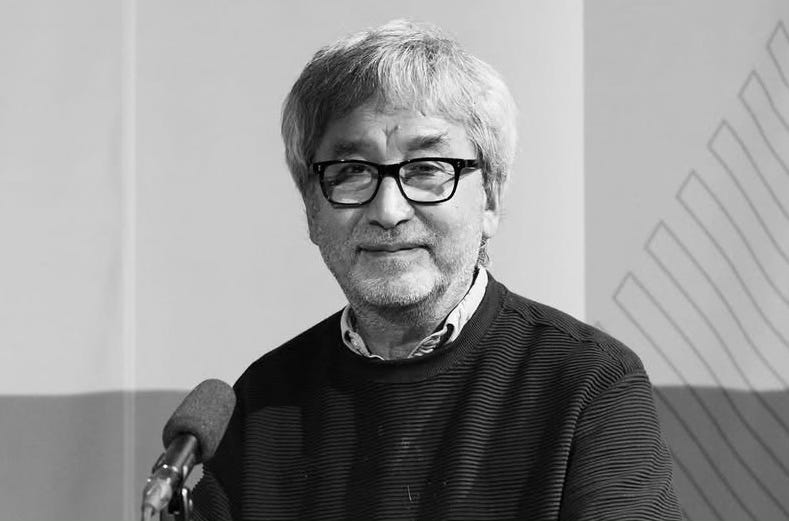

This week, we’re talking to Uzbekistan’s most prominent writer, Hamid Ismailov. He is a longtime BBC and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty journalist, and the author of numerous works of fiction and poetry in several languages. He is the recipient of the EBRD Literature Prize for his novel The Devils’ Dance – sometimes called “an Uzbek Game of Thrones.” His latest novel, We Computers, has been the finalist of the 2025 National Book Award for Translated Literature, one of the most prestigious literary prizes in the U.S. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Our guest this week is one of the most fascinating contemporary scholars from Kazakhstan and the author of What Does It Mean to Be Kazakhstani - Diana Kudaibergen, a cultural and political sociologist and Lecturer in Central Asian Politics and Society at University College London. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

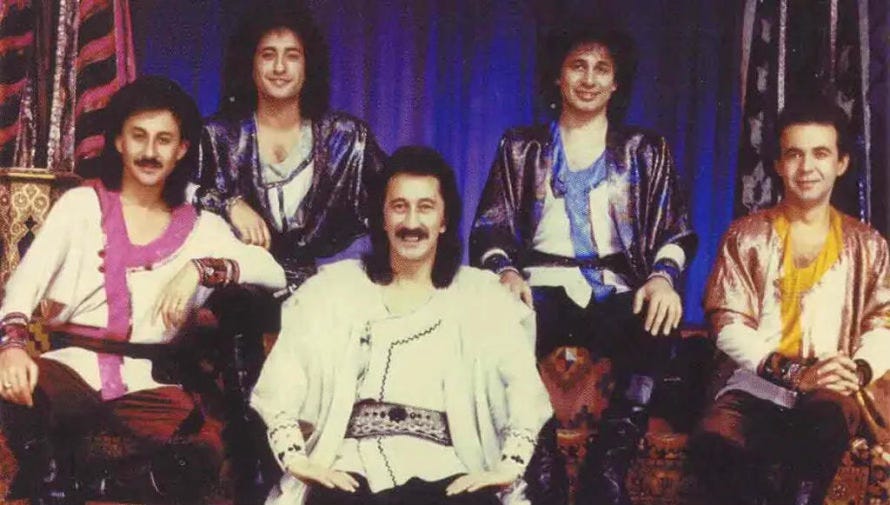

Hi all,Our guest today once shared with me a fascinating story. Back in 1981, when the Uzbek pop group Yalla was touring Uzbekistan, they passed through the town of Uchkuduk — a name worthy of a song. Yurii Entin, one of the band’s lyricists, supposedly wrote it in just 40 minutes. Little did he know that his quick scribbles would go on to make history in Uzbek and Soviet pop music.Uchkuduk, a song about a small town in Uzbekistan, became so popular that the authorities banned it from the airwaves for an entire year, fearing it would draw attention to the area’s main industry: uranium mining. According to legend, the song made the band so recognizable that when its frontman, Farrukh Zakirov, once came to the Kremlin Palace for a concert, a security guard simply said: “Oh, Uchkuduk — come right through.”If you haven’t yet, I’d love for you to become a paying subscriber — it makes a huge differenceThis episode is a special one: we’ll talk about Central Asian music in Soviet times, and about the history of the region as told through music. Joining us is Leora Eisenberg, a fifth-year PhD student at Harvard University, where she studies Soviet and Central Asian history, with a special focus on Soviet estrada, in other words, the pop music, of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.Leora has kindly shared with us one of her favorite playlists of Soviet Central Asian estrada. You can find it here: My fellow Poles will even find a little surprise there: one of the songs is a Kazakh remake of Szła dzieweczka do laseczka, a folk tune that needs no introduction.Hope you will enjoy this one!Have a great end of the week,— Agnieszka Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Hi all,I’m writing and recording this week’s intro from my new home in Almaty. The weather is perfect, as it so often is in late summer. I spend my days getting to know my neighborhood, walking my dog, meeting friends old and new, and writing. I’m very grateful to be back in Central Asia after almost four years in Europe. I hope Almaty will be a good host for me — and for Turan Tales. If any of you, dear listeners, are around, make sure to drop me a line.This week’s guest and I will be discussing a topic that always draws a lot of attention: first daughters and the female face of Central Asian politics. Since the five Central Asian republics gained independence, there has been no shortage of presidential daughters. Some have been famous, audacious, and highly ambitious, like the legendary Gulnara Karimova and Dariga Nazarbayeva. Others have been more low-profile but still played important roles in their fathers’ administrations, such as the Mirziyoyev sisters or some of the many daughters of Tajikistan’s president, Emomali Rahmon. And some are only now stepping out of the shadows, like Oguljahan Atabayeva from Turkmenistan.Regardless of their public profile, all of them play a role in preserving their fathers’ rule. The questions are: Could any of them succeed their father? Could a woman ever become president in Central Asia? And what role, if any, do first daughters play in changing the position of women in their respective countries?Joining us is Galiya Ibragimova, an Uzbekistan-born freelance journalist and researcher focusing on political transformation in Central Asia and Eastern Europe. She is also a PhD candidate in political science at the University of World Economy and Diplomacy in Tashkent.I hope you enjoy this one!Have a great end of the week,— Agnieszka Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

The Caspian Sea is shrinking, its shores littered with seal carcasses. For scientist Assel Baimukanova, each one tells the story of an ecosystem on the brink. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week, we’re taking a deeper look at Central Asia’s postcolonial legacy and how Russia’s centuries-long influence has shaped ways of thinking, institutions, and everyday life in the region.Russian colonisation of Central Asia began in the early 1800s and expanded steadily throughout the 19th century. Following the Russian Revolution, most of Central Asia was incorporated into the Soviet Union. This period brought rapid industrialisation and infrastructure development – but it also suppressed local cultures in a manner typical of colonial regimes.The Russian language came to be seen as a marker of civilisation and positioned as superior to local languages, while people were expected to conform to the values of a secular, rational Soviet state.To meet the demands of the increasingly authoritarian new super-state, millions of people, representatives of ethnic groups seen as suspicious and potentially rebellious, were deported to Central Asia.GULAGs, that is - forced labour camps - were established across the Soviet periphery. Finally, man-made famines – driven by brutal collectivisation policies – claimed thousands of lives in both Central Asia and Ukraine. The ethnic and demographic makeup of the region was permanently altered.And yet, some scholars – both in Russia and the West – continue to argue that the Soviet Union was not an empire, but rather a benevolent force striving to build a just, multicultural society.Even in modern-day Central Asian states, which gained independence after the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, many still express nostalgia for the Soviet past, often overlooking its darker chapters. Russian remains widely spoken – and for many, it is still the only language they know.Today, we will look at all those paradoxes, explore Soviet nostalgia and imperial melancholia, focusing on a rarely heard perspective: that of Turkmenistan.Joining us is Selbi Durdiyeva, a decolonial scholar originally from Turkmenistan, and a Teaching Fellow at the College of Law, Anthropology and Politics, at SOAS, University of London. Her research interests include decoloniality, transitional justice, and socio-legal approaches. Her book titled “The Role of Civil Society in Transitional Justice: The Case of Russia” was published by Routledge in 2024. She is also my Substack colleague and runs a newsletter called “Nodes from Pluriverse.” Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week we are revisiting the legacy of one of the most important figures who shaped Central Asia following the collapse of the Soviet Union: Nursultan Nazarbayev, the former president of Kazakhstan.Born in 1940, Nazarbayev served as Kazakhstan’s first president from 1991 until 2019, when he stepped down and transferred power to Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, then Chairman of the Senate – and the current president.Like all Central Asian leaders, Nazarbayev left behind a mixed legacy. While he sought to be remembered as the Leader of the Nation – Elbasy – and the founding father of modern Kazakhstan, many continue to associate him with autocratic rule and widespread corruption.In 2022, following mass protests – known as Qantar, or Bloody January – in which more than 200 people likely lost their lives, Nazarbayev was stripped of his Elbasy title and his position as chairman of the Security Council, a role that was originally intended to be held for life.To discuss Nursultan Nazarbayev, his presidency, and his legacy, we are joined by Joanna Lillis, a Kazakhstan-based journalist with two decades of experience reporting from Central Asia. She is the author of Dark shadows: Inside the secret world of Kazakhstan and the upcoming Silk mirage: Through the looking glass in Uzbekistan, set to be published this autumn. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe