Discover Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time Podcast

Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time Podcast

Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time Podcast

Author: Behind-the-scenes stories and research on growing up in Korean society.

Subscribed: 9Played: 204Subscribe

Share

© Jiwon Yoon

Description

Welcome to Growing Up in Korea – The Audio Series

I’m Dr. Jiwon Yoon, a writer and former professor exploring what it means to grow up in Korean society—through the lens of education, parenting, and social pressure.

Each episode features an audio version of my essays—narrated using Google’s NotebookLM, an experimental tool that turns my notes and research into a conversational voice.

While the voice is AI-generated, every idea, note, and reference comes from my own research—often the parts that didn’t make it into the final written piece.

Think of this as a behind-the-scenes layer: the thoughts I underlined, the stories I couldn’t fit, the questions that kept me thinking.

I hope you’ll find something here that sparks reflection and conversation.

yoonjiwon.substack.com

I’m Dr. Jiwon Yoon, a writer and former professor exploring what it means to grow up in Korean society—through the lens of education, parenting, and social pressure.

Each episode features an audio version of my essays—narrated using Google’s NotebookLM, an experimental tool that turns my notes and research into a conversational voice.

While the voice is AI-generated, every idea, note, and reference comes from my own research—often the parts that didn’t make it into the final written piece.

Think of this as a behind-the-scenes layer: the thoughts I underlined, the stories I couldn’t fit, the questions that kept me thinking.

I hope you’ll find something here that sparks reflection and conversation.

yoonjiwon.substack.com

47 Episodes

Reverse

Why do Koreans call boiling soup “refreshing”? Why does warm water show up in K-dramas before advice ever does? In this companion episode to my newsletter, we follow the logic of siwonhada (시원하다) into ondol (온돌), Korea’s heated-floor system, and trace how warmth became architecture, medicine, and a way of caring for people. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Quick audio noteA small behind-the-scenes update: I used to record this podcast with a clip-on mic plugged into my phone, sitting in my walk-in closet. My husband felt sorry for me and surprised me with a real microphone for my birthday in early February. So now I’m recording at my desk, like a proper adult. I’m still learning the settings, though, so you may hear a few little volume jumps or pops. Sorry if it’s distracting. I’m working on it, and I’ll keep improving the sound.============================Why do Koreans treat cold like it’s a force that can sneak into your body, especially when you’re sick? In this companion episode to my Substack essay, I linger in the everyday details: flu season anxiety, the reflexive “no ice, please,” and the quiet Korean belief that recovery is not just a diagnosis. It’s an environment.We talk about “cold energy” (찬기), gi-un (기운), and the logic behind the hot pack, the heated blanket, and that mysterious undershirt (내복) your Korean mom insists is non-negotiable. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

This is the companion episode to this week’s newsletter, but it goes deeper into what I couldn’t fully hold on the page.I talk about what “Gwangju” means in the Korean nervous system, why certain places become stages for power, and why democracy rarely moves forward on autopilot. I also reflect on Korea’s exhausting cycle of backsliding and accountability, and why Minnesota, right now, looks like a community refusing to normalize coercion through real civic follow-through.If you have been feeling tired, cynical, or numb lately, I made this episode with you in mind.It is also a small reminder I keep returning to: power is borrowed, not owned. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Editing this episode, I noticed my voice sounds a little different.Maybe it is because my sleep has been shaky lately, with panic creeping back in at night. Maybe it is because I recorded earlier than I usually do. Or maybe it is simply because this story asks for a different kind of honesty than my usual episodes.In today’s episode, I share how political despair in Korea first became physical for me during my PhD years, how I learned to live through panic, and what “healing” has looked like for me. Not as a clean before and after, but as something I still work on, even now. And somewhere inside this story, you may also understand why I stayed away from Korea for eight years, and how my husband became the one who cooks for our family.If you would like to read along, the original essay version of this episode is on Substack. It is the same story, just in written form, with a little more space to pause, reread, and sit with certain lines. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

“Wait and see” sounds calm in English. In Korean parenting culture, it can feel like negligence.In this episode, I’m introducing a Korean book that hasn’t been translated into English: The Sociology of Marriage and Childcare by Oh Chan-ho (결혼과 육아의 사회학, gyeol-hon-gwa yuk-a-ui sa-hoe-hak). It’s part of a series I do about once a month, where I bring English-speaking listeners inside Korean books and ideas that often stay behind the language barrier.We’ll trace how Korea’s caregiving instinct evolved from survival mode (mountains, wars, and folk remedies) into something more modern and sneakier: a system that turns parental worry into measurable tasks, purchases, and performance reviews. We’ll talk about maternal love (모성애, mo-seong-ae), parenting as evaluation, and why a Korean baby expo can feel less like shopping and more like a crash course in anxiety.Companion: This episode pairs with my Substack essay, Why Korean Parents Can’t “Just Wait and See.” Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

What do you do first when your child gets sick?Check symptoms, open the patient portal, set timers, preserve bedtime routines?When my 7-year-old spiked a fever, my body did something else. It reverted to a Korean instinct I call distance zero: closing the space, staying close, and letting touch do part of the work.This episode is personal, a little funny, and unexpectedly tender. It is about the hidden “grammar” of care, and what our bodies remember even after decades in a different culture.This podcast episode was created from my Substack essay: Distance Zero: Inside Korean Caregiving When a Child Gets SickBut it is not a read-aloud. Think of the essay and the episode as a matched set.Read the piece for the clean framework and the research.Listen to the episode for the scenes, the memories, and the parts I could not fit on the page.What you will hear in this episode1) The “geography of care”Why some cultures treat space as recovery, and others treat closeness as responsibility.2) Touch as languageIn the U.S., we often coach children to describe symptoms and name feelings.In Korea, we do that too, but we also speak through our hands.3) The practices I grew up withThis is where the podcast goes more personal than the newsletter.Have you ever heard of bee venom therapy (봉침)? My mother learned it at a Korean medicine clinic, brought it to Thailand, and yes, she used it at home.Also yes, she literally kept bees on my younger brother’s balcony.If you think that sounds like a sitcom plot, you are not alone.I also share memories of su-ji-chim (Korean hand acupuncture) and how these tactile traditions shaped what my hands do automatically when my daughter is hurting.A Quick NoteI am not a doctor, and I am not giving medical advice. The stories about bee venom and acupuncture are cultural reflections of my lived experience. Please consult your pediatrician for any health concerns!I would love to hear your thoughts after you listen. What is the first thing your body does automatically when your child gets sick? Is it space, or is it “Distance Zero”?Enjoy the episode, and see you next week! Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Happy New Year! 새해 복 많이 받으세요!This is my first episode of 2026, and it comes as a companion to this week’s Substack essay. It’s not a word-for-word reading. Think of it as the version I’d tell you over coffee. If you read the post and then listen, you’ll get the full picture.This year, I’m leaning into what this show was always meant to be: Understanding Korea, one story at a time. Lighter on the inbox, deeper in the long run, with the book getting its own separate space to grow. If you listen to this episode, you’ll have a clearer sense of where I’m headed and what I’m building this year.One little surprise to start 2026: FeedSpot recently ranked this podcast #2 among AI-generated podcasts and #26 on its NotebookLM-generated podcast list. I’m recording in my own voice now, but I’m genuinely glad those early experiments are still finding listeners. And the roundups include plenty of other great shows too, so take a look! Thanks for being here. If you enjoy the show, subscribing and sharing it helps more than you know. It’s one of the simplest ways to help new listeners discover the podcast.See you next week. Bye! Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

This episode is the audio “director’s commentary” to my latest Substack essay in the K-Book Uncovered series, where we have been walking through Yu Si-min’s My History of Contemporary Korea (나의 한국 현대사) together. If Korea’s modern history were a movie, 1987 would be the perfect place to roll the credits. The crowds win. The generals step back. Democracy arrives. The end.Except... Yu Si-min refuses to end the story there.In this finale, we ask the quiet, uncomfortable question that doesn’t make it into history movies: Once you finally win democracy and development, what do you actually do with them?We’ll walk through:• The “roommate situation” between Korea’s industrialization and democratization camps after 1987• The 1997 IMF crisis, when the floor dropped out and the old promises shattered• Four new desires reshaping Korea today: fairness, safety, rest, and belonging• Why the protests keep coming—from candlelight seas to K-pop light sticks• And what “limited pride” means in a country that’s both a miracle and a messThis episode is designed to complement this week’s Substack essay. If you can, read and listen together—they complete each other like stereo sound.A Few Personal Notes:This is my last podcast of the year. Next Monday (Dec 22), I’ll publish one final bonus essay: a deep dive into Yu Si-min’s What is the State? (국가란 무엇인가), the philosophical companion to the history we just walked through.After that, I am finally going to practice something Koreans are famously bad at: rest. I’ll be taking a break until January 15 to spend unhurried time with my family.Before I go, I need to say thank you. This year, you’ve been listening from 82 countries—with the US, Indonesia, and Korea leading the way. To everyone who let me whisper into your ears while you commuted, cooked, or scrolled in bed: thank you for caring about this small peninsula and letting Korea’s story speak into your own.I’ll see you in 2026. Take care, rest if you can, and thank you for listening—and for reading.— Jiwon Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

This podcast episode is the audio companion to my newsletter essay:“Two Desires, One Nation, Part 3: The City That Would Not Stay Silent”Read first? You’ll get the photos, timelines, and historical context.Listen first? You’ll get the feeling, the emotional core I couldn’t fit into 3,000 words.Both together? That’s the full experience.Here’s a question: Why do Koreans protest so much?No, seriously. Every few years, millions take to the streets. Light sticks. Chants. Grandmothers and college students side by side.Western media always say, “Koreans are passionate about democracy.”Sure. But why?This episode is about the why.What You’ll Learn:* 부채감 (buchae-gam): The Korean word that has no English translation, but explains everything* The photo that changed history: How one image of Lee Han-yeol became a symbol of moral debt* The “necktie troops”: Why office workers in suits joined student protesters in 1987* Gwangju’s seven-year silence: The hidden massacre that became Korea’s original debt* Why 2024 felt like 1987 — From Yoon Suk-yeol’s martial law to impeachment in daysA Taste of What’s Inside:“Rage burns hot and fast. You can be furious for a week, a month, maybe a year. Then it fades. But debt? Debt doesn’t go away. It sits in your chest. It wakes you up at 3 a.m. It whispers, ‘You’re still alive. They’re not. What are you going to do about it?’”“Democracy, in Korea, has names and faces. Park Jong-chul. Lee Han-yeol. 166+ people in Gwangju. You don’t just ‘care about democracy.’ You fight for it like your life depends on it because someone else’s did.”“There’s a saying: Democracy doesn’t grow in fertile soil. It grows in blood.”Why This Episode Hits Different:This isn’t just history. It’s personal.Because 부채감 (buchae-gam) isn’t just something Koreans felt in 1987.It’s what brought millions into the streets in December 2024.It’s why the impeachment process began within days, not weeks or months.It’s why Korean democracy looks the way it does: urgent, loud, uncompromising.If you’ve ever wondered why Koreans don’t take democracy for granted, this episode will answer that question.About This Series:This is Part 3 of 4 in my deep dive into Yu Si-min’s My History of Contemporary Korea (나의 한국 현대사), a book that’s never been translated into English, but should be required reading for anyone trying to understand modern Korea.Missed the earlier episodes?→ Part 1: Twins Born in the Ruins→ Part 2: The Barracks State & The Boy Who Refused to Bow→ Part 4: Coming next week Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Hello, everyone.Last week, we stood at “Ground Zero.” This week, we enter the “Barracks State.”In this week’s newsletter (Part 2), we covered the history of the 1960s and 70s—the economic explosion, the dictatorship, and the tragic death of Jeon Tae-il.But in this podcast episode, I want to go behind the text. I want to talk about the emotional and psychological weight of living in a country that tried to turn its citizens into soldiers and machines.I talk about Park Chung-hee’s “Barracks State,” why so many people accepted that level of control, and how the slogan “Let’s live well” powered the economic miracle while grinding down real human bodies. We also spend time with two people who shape the way I read this history: Yu Si-min himself and a young garment worker named Jeon Tae-il, whose final cry was, “We are not machines.”This episode is not just an audio version of the article. It is meant to complement it. The newsletter gives you the structure, photos, and key quotes; the podcast lingers on the emotions, the contradictions, and the questions I could not fit on the page.🔗 Read the full Part 2 essay here:Two Desires, One Nation, Part 2: The Barracks State and the Boy Who Wouldn’t BowIf you are new to this series, you might also want to start with Part 1 for the origin story of our “twins”:Part 1: The Twins Born in the RuinsThank you for listening, and I hope you will enjoy reading the piece and then hearing the story unfold in your ears. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Hello everyone! Last month, I started a monthly K-Book Uncovered series, where I explore essential Korean books that haven’t yet been translated into English. We began with historian Kim Won’s The June 1987 Uprising (87년 6월 항쟁), a vivid chronicle of the democracy movement that forced Korea’s military regime to accept direct presidential elections.This month, we moved one step wider in scope.In the newsletter, I’m doing a four-part deep dive into Yu Si-min’s My History of Contemporary Korea (나의 한국 현대사), using his frame of two rival camps—industrialization and democratization—to understand how Korea went from ruins and dictatorship to K-pop, K-dramas, and candlelight protests.While the newsletter focuses on the historical narrative—the “Fraternal Twins” of Industrialization and Democracy—I realized that some of the most powerful insights in the book are psychological and emotional. They didn’t quite fit into the historical timeline, but they are absolutely essential for understanding why Korea feels the way it does today.So, I recorded a podcast episode to complement the written series.In this episode, we go off-script to discuss:* The “Refugee Mentality”: Why South Korea in 1959 wasn’t just a poor country, but a “refugee camp masquerading as a nation,” and how that anxiety still drives the hyper-competition of today.* The “Cool Kid” of the 1950s: The shocking reality that, for a long time, North Korea was actually the more successful sibling.* Radical Empathy: Yu Si-min’s moving explanation of why the older generation votes for conservative leaders (hint: it’s not just “brainwashing.” It’s about validating their own survival).* “Limited Pride”: Why loving Korea means accepting that it is both an ugly and a beautiful country.Think of the newsletter as the “Textbook” and this podcast as the “Coffee Chat” afterwards. Even if you’ve already read the article, this episode adds a whole new layer of context and emotion that will change how you see the history we are exploring.I hope you enjoy this deeper look.A small Thanksgiving note from Seattle (via Vancouver)As I’m releasing this episode, Thanksgiving is just starting here in the United States.Traditionally, it’s a holiday for gathering with extended family, but in our case, most of our relatives live in other countries. So our little family of three has developed our own tradition: on Thanksgiving, we usually drive up from the Seattle area to Vancouver, Canada, our “next-door neighbor” across the border.By the time you’re listening to this, I’ll probably be somewhere between rain clouds, coffee shops, and bookstores in Vancouver, trying to keep my 7-year-old entertained and sneaking in a few pages of Korean history whenever I can.Wherever you are, I hope this week brings you at least a few moments of genuine rest and small, surprising things to be grateful for.Thank you, as always, for listening, for reading, and for caring enough to understand Korea one story at a time. 💛I hope you enjoy this week’s episode: “The Twins Born in the Ruins.” Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Dive into South Korea’s turbulent cultural history under authoritarian rule. This episode unpacks how dictators used censorship alongside the 3S Policy—Sex, Sports, and Screens—to control pop culture, silence dissent, and inadvertently spark a resistance movement. Hear stories of banned songs, erotic cinema, rigged baseball leagues, and hidden books fueling democracy. Includes short clips from banned songs to give you a real feel for the era’s soundtrack.Whether you know Korea or are new to its stories, this episode connects culture and politics with vivid examples and lively commentary. Music excerpts used under fair use for commentary and education.🔗 Want to read the full post? Click here Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

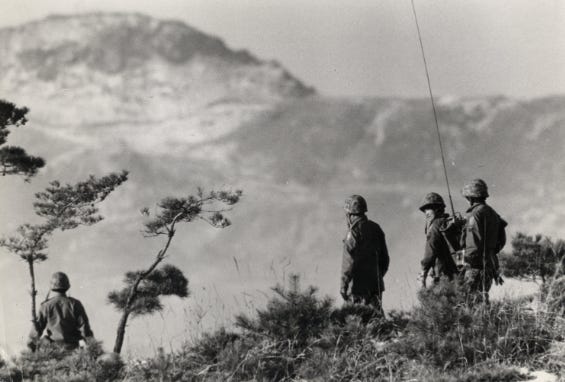

A Nation in Uniform: How Emergency Became Everyday in South KoreaSummaryAfter the 1968 shocks, South Korea rebuilt everyday life around emergency. This episode looks at how the state turned men into reserve soldiers, schools into drill grounds, and citizens into trackable numbers. It is the “hardware” of the garrison state that sat on top of last week’s “software” of laws, policing, and ideology.What’s inside1968 aftershocks: Blue House Raid and the Uljin–Samcheok landingsHardware 1: Yebigun (reserve forces) and the monthly culture of readinessHardware 1.5: Minbangwi (Civil Defense Corps), blackout drills, and why the upper age later dropped to 40Hardware 2: Gyoryeon (school military training), plus Jihyun’s memories from classHardware 3: Resident Registration Number, the 12→13-digit ID, and embodied surveillanceThe “iron triangle” recap and what slowly changed after democratization📝 Read the original full essay here🎨 See Jihyun’s graphic novel about this era hereThanks so much for listening. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Original Post- 33(23). GOVERNANCE BY FEAR — When "National Security" Became the Perfect ExcuseIn 1968, real North Korean commandos almost assassinated the South Korean president. The threat was real.The state's response? To build a "Garrison State"—a system of total control pointed not at the enemy, but at its own citizens.How do you build an invisible prison for an entire nation? In this episode, we break down the three engines of control that made it possible.In this episode, you'll learn about:Engine 1: The Law Discover the National Security Law—a vague, powerful legal weapon that criminalized thought. Find out how mentioning Picasso or quoting Marx could be redefined as "treason."Engine 2: The Spies Meet the KCIA, a secret police that enforced the law with terror. We explore how they fabricated entire spy rings, like the "People's Revolutionary Party Incident," to conduct "judicial murder" and turn neighbors against each other.Engine 3: The Ideology "I Hate Communism" wasn't just a slogan; it was a national identity. Host Jiwon Yoon shares a chilling, personal memory of winning a silver medal in an anti-communist speaking contest as a child.This is the story of how a real fear was amplified, weaponized, and turned into the perfect excuse for total control.Coming Up Next Week: We explore the hardware of the Garrison State—how daily life itself was militarized. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Why this sounds differentI’m rebuilding the podcast to feel more personal. No more auto-generated audio. You’re hearing this in my own voice. Posts go out on Thursdays and the podcast comes out on Tuesdays.Today’s episodeI launch “K-Book Uncovered,” a monthly pick of vital Korean books not yet in English. This week: Kim Won’s The June 1987 Uprising. We revisit the June Democracy Movement through three lenses: office workers in Seoul, labor organizers in Incheon, and a delivery worker in Busan. We look at what sparked the protests, why experiences differed by class and region, and how “historical imagination” helps us read history from the ground up.Read the full essayFull write-up on Substack: https://yoonjiwon.substack.com/p/korea-1987-democracy-uprisingTell me what you thinkYour feedback really helps. Comments, suggestions, or quick thoughts are all welcome. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Hello, curious minds,This week I share a personal update, what is changing with the newsletter, and how you can support the work.Starting next week, I will publish the first-ever post exclusively for paid subscribers.But first, let me make one thing perfectly clear: The in-depth weekly essays and podcasts you receive every Thursday will always remain free for everyone. That is my promise.At the same time, I’ve long dreamed of becoming a full-time writer, creating deeper stories that require even more time and research. Until now, I’ve been funding this newsletter by taking on other research and consulting projects. But my goal is to dedicate much more of my energy to this space and to a book I’m working on about Korea’s democracy. That’s why I recently turned on the paid subscription option.Even without a single paywalled post, a few of you have already upgraded to paid. I was so touched and grateful for that vote of confidence.As the first step toward this dream, I’m launching a new monthly series for paid members.📚 Unlocking Korea’s Hidden Library: A Series for Paid MembersIn this series, I’ll introduce and deeply analyze books that are essential to understanding modern Korea but are not yet available in English. Each month, I’ll share a piece that explores what the book reveals about Korean society, who wrote it, and why it matters now. Together with my wonderful collaborator, webtoon artist Jihyun Lee, we’ll craft each piece so you can feel like you’re discovering the hidden context within the book itself.🌟 Become a Founding MemberTo thank those who want to support this new journey, I’m offering a special, one-time discount.Become an annual paid subscriber by November 30th, and you can lock in the founding member rate of $30/year forever. On December 1st, the annual price will increase to $50/year. If you join now at the founding rate, your price will never increase upon renewal. Ever.Your paid subscription is the most direct way to support this work, allowing me to dedicate more time to in-depth research and writing. It is the single biggest driver of this newsletter’s sustainable growth.So, What’s Changing?👍 For Free Subscribers (Your great experience continues!)* Weekly essays on Korean history, culture, and politics* In-depth analysis based on Korean-language sources* Podcast-style audio versions of posts so you can listen on the go✨ For Paid Subscribers (Get everything above, plus exclusive benefits!)* [NEW] The monthly members-only series, Unlocking Korea’s Hidden Library* Full access to the entire archive of paid posts* The ability to comment on all posts and join community discussionsOther Ways to Join & Support💰 Group Subscriptions: Better with friends!Get a 20% discount when 2 or more people subscribe together for an annual plan. During the founding member window (through Nov 30), that’s just $24 each!Learn more: Subscribe to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time💌 Refer Friends, Earn Free Months!If you enjoy Understanding Korea, it would mean the world if you shared it with friends. When you use your personal referral link below (or the Share button on any post), you’ll earn complimentary time on your paid plan:* 3 referrals → 1 month free* 5 referrals → 3 months free* 10 referrals → 9 months freeTimeline at a Glance* Last week of Oct: The first paid-only post from the Unlocking Korea’s Hidden Library series. Get ready: we’ll be diving into a book by a historian who was a direct participant in South Korea’s democratization movement.* Through Nov 30: The founding member price window ($30/year) is open.* Dec 1: The annual price returns to $50.* Mid-Dec: I’ll be taking a short family break for about two weeks. I’ll use the time to refresh, study, and come back in January with even better stories for you!Where to Listen, Watch, and ConnectI recently gathered all my sites in one place.If you’re on social media beyond Substack, let’s connect there too! - https://www.jiwon-yoon.com/links/If you have any questions about the paid plan, please reply to this email. And if there’s a Korean book you think I should evaluate for the new series, don’t hesitate to tell me.Thank you for being here and for joining this journey to make Korea more understandable, one story at a time. Whether you choose to remain a free reader or become a paid member, you are a valued part of the Understanding Korea community.I am so excited about the stories we will continue to explore together.Warmly,Jiwon Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

31(21). The Security Prison: North Korea as Mirror, Memory as WeaponHow Korea’s Cold War became a domestic surveillance system—and how writers fought to remember what the state erasedThis episode opens on a winter night in 1968 Seoul, when 31 North Korean commandos nearly reached the Blue House. But their failure became something larger: proof that the war never ended. From that fear, the South Korean state built not just a military—but a memory regime.We trace how North Korea became both ghost and mirror, how Park Chung-hee’s regime invoked “security” to justify dictatorship, and how anti-communism became a license to control thought, family lineage, and even grief. From the 7.4 Joint Statement to the Yushin Constitution, we examine how peace-talk optics masked deeper entrenchments of power.But the heart of this episode is literary. We explore the novels that bore witness—Jeong Ji-a’s stories of yeonjwaje, Hwang Sok-yong’s indictment of love under surveillance, and Han Kang’s Nobel-winning elegy for the voiceless in Gwangju. These stories didn’t just resist censorship—they reclaimed the right to speak, to remember, and to grieve.Original post & full show notes: https://yoonjiwon.substack.com/p/korea-security-prisonEp. 31(21) — Glossary of Key Korean Terms(Romanization · Hangul · Meaning — timestamps show first mention; app variances ± a few seconds.)Park Chung-hee · 박정희 — 1:19 Military dictator (1961–1979) whose regime fused Cold War logic with industrial modernization—and extreme domestic control.Kim Il-sung · 김일성 — 4:14 North Korea’s founding leader. From the 1960s–70s, his provocations helped justify authoritarian crackdowns in the South.Pyongyang · 평양 — 4:18 North Korea’s capital, seen from the South as both enemy stronghold and estranged twin city.Yushin Constitution · 유신헌법 — 5:22 The 1972 legal framework that extended Park Chung-hee’s rule indefinitely—essentially legalizing dictatorship.yeonjwaje · 연좌제 — 6:37 “Guilt by association.” A system under which children of dissidents could be denied jobs, education, or civil rights.Jeong Ji-a · 정지아 — 6:55 Author of Daughter of a Partisan and A Father’s Liberation Diary, both based on her real-life parents who were former partisans. Her novels fictionalize their lives under surveillance, exile, and erasure—bearing witness to how South Korea’s security state punished families across generations.Han Kang · 한강 — 8:35 2024 Nobel laureate and author of Human Acts, a novel on the Gwangju Uprising’s grief, silence, and memory.Gwangju · 광주 — 8:44 Site of the 1980 pro-democracy uprising. The state's violent suppression of it became a literary and moral touchstone.Hwang Sok-yong · 황석영 — 9:06 Author of The Old Garden, a love story set during South Korea’s dictatorship that explores surveillance, memory, and resistance. Hwang was imprisoned for attending a North Korean literary conference in 1989. A leading voice in modern Korean literature, his other major works include The Guest (about the Sinchon Massacre and divided memory), The Road to Sampo (capturing displacement in industrializing Korea), and Princess Bari (a mythical refugee tale crossing borders and trauma).Choi In-hun · 최인훈 — 9:43 Wrote The Square, a landmark post-war novel on ideological paralysis and divided identity.Cho Se-hui · 조세희 — 10:12 Wrote The Dwarf, capturing how “anti-communism” masked state-led economic violence against workers. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

30(20). How Trauma Built Modern Korea: From "Ppalli-Ppalli" to the Miracle on the Han RiverThe postwar survival algorithm—speed, education, real estate, and han—behind South Korea’s rapid riseEpisode summaryThis episode traces how the Korean War’s unresolved grief—ambiguous loss, hypervigilance, and a family-as-fortress mindset—evolved into a national operating system: ppalli-ppalli speed, education as an indestructible asset, real estate as a tangible anchor, han as fuel, and village-style mutual aid. We follow that code from expressways and apartments to cram schools and conglomerates—and we confront the bill: burnout, gwarosa (death from overwork), and a mental-health strain that shadows the “Miracle on the Han.”Original post & full show notes: https://yoonjiwon.substack.com/p/how-trauma-built-modern-koreaEp. 30(20) — Glossary of Key Korean Terms(Romanization · Hangul · Meaning — timestamps show first mention; app variances ± a few seconds.)ppalli-ppalli · 빨리빨리 — 1:28 Literally “hurry-hurry.” The shorthand for Korea’s speed reflex—reply fast, build fast, ship fast—rooted in postwar survival logic.Park Chung-hee · 박정희 — 2:55 South Korean president (1963–1979). Drove state-led industrialization and export-oriented growth; also synonymous with authoritarian rule.Gyeongbu Expressway · 경부 고속도로 — 3:11 The Seoul–Busan highway, completed in 1970 on an accelerated timetable—an emblem of “build fast” development.Seoul · 서울 — 3:14 South Korea’s capital; massive urban expansion, especially south of the Han River, defined late-20th-century growth.Busan · 부산 — 3:15 Major southern port city and wartime refuge; the south anchor of the Gyeongbu corridor.ugoltap (“cow-bone tower”) · 우골탑 — 4:45 A biting phrase from the 1970s–80s: selling the family cow to fund university—i.e., the family burden around education.ingoltap (“human-bone tower”) · 인골탑 — 5:03 A darker update of ugoltap: university “towers” built on parents’ back-breaking sacrifice—social critique of education costs borne by families.hagwon (cram school) · 학원 — 5:22 Private after-school institutes for test prep, languages, music, etc.; core to the education arms race.han · 한 (恨) — 6:43 A debated concept: a knot of sorrow, grievance, and resolve. In this episode, it frames how loss can harden into motion — “never this helpless again.”jaebeol (chaebol) · 재벌 — 7:48 Family-controlled conglomerates central to Korea’s rise (e.g., Samsung, LG, Hyundai); vast scope and complex legacies.Samsung / Hyundai · 삼성 / 현대 — 7:50 Flagship chaebol groups; their founding lore often symbolizes grit, speed, and scale in high-growth decades.dure · 두레 — 9:31 Traditional village work teams for collective farming; a form of mutual aid.pumasi · 품앗이 — 9:37 Reciprocal labor exchange between households — “help me today, I help you tomorrow.”Saemaul Undong (New Village Movement) · 새마을운동 — 9:59 1970s rural modernization drive channeling community labor and state resources into roofs, roads, and waterworks.gwarosa (death from overwork) · 과로사 — 11:48 Fatal outcomes linked to chronic overwork and stress—the pressure-cooker cost of speed.Han Kang (novelist) · 한강 — 12:43 Nobel Prize in Literature (2024) and International Booker Prize (2016)–winning South Korean novelist (The Vegetarian, Human Acts, Greek Lessons). In this episode, we introduce her as a writer whose fiction lays bare the pain and contradictions of modern Korean society. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Ep. 29(19). The Korean War Never Ended: Family Trauma Across Generations -The true cost of separated families, silence, and survival in modern KoreaThis episode uncovers how the unresolved grief and invisible aftermath of the Korean War have quietly shaped Korean families for generations.We revisit the lived experiences of war survivors, exploring why, even today, nearly every Korean family shares a table with a “ghost” — the presence of missing loved ones whose fate was never truly known.Original post and show notes: https://yoonjiwon.substack.com/p/korean-war-separated-familiesEp. 29(19) — Glossary of Key Korean Terms(Romanization · Hangul · Meaning — timestamps show first mention; app variances ± a few seconds.)“Isangajogeul Chajseumnida” · 이산가족을 찾습니다 — 3:28 Direct translation: “Finding Dispersed Families.”KBS’s 1983 live TV marathon that reunited thousands of people separated by the Korean War and later entered UNESCO’s Memory of the World. Think: a nation-wide, 138-day on-air search for missing relatives.Bodo League Massacre · 보도연맹 학살 — 6:35Mass killings of suspected leftists and alleged members of the National Guidance League (Bodo Yeonmaeng) during the early months of the Korean War—a horrific episode carried out in South Korea, which deeply shattered social trust.Isan gajok (Separated families) · 이산가족 — 12:40Families split by the 1950–53 war and the division of Korea. Many never received proof of death or survival—what psychologists call “ambiguous loss.”Geumgangsan (Mt. Kumgang) · 금강산 — 13:08 A spectacular mountain in North Korea, famed for sheer cliffs, autumn foliage, and coastal views. It also hosted inter-Korean family reunions (notably in 2009 and 2018). In 2025, North Korea began demolishing the Reunion Center facility, dimming hopes for future large-scale meetings. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe

Episode 28 | The Three-Year Inferno — Civilian Loss, Suppressed Mourning, and an Unfinished WarTo understand modern Korea, you have to walk through 1950–53. This episode, drawn from my Substack series, explores the brutality of the Korean War and the operating system it left behind: a country standing not on peace but on waiting.Original Post: https://yoonjiwon.substack.com/p/korean-war-brutal-historyKey themesWhy this was not just a soldiers’ war but a catastrophe that swallowed kitchens, schools, and bridges.How hunger, cold, bombing, and checkpoints turned daily life into survival tactics.“Our own hands, too”: North Korean, Chinese, South Korean, and UN/US forces all left civilian victims.The right to mourn and ambiguous loss—how missing names froze grief.Armistice as operating system: conscription, drills, and emergency politics as a lasting tempo.Glossary of Key Korean Terms (Romanization · Hangul · Meaning)(Timestamps mark the first mention; your app may vary by a few seconds.)Bodo Yeonmaeng haksal · 보도연맹 학살 · 4:01Mass executions tied to the National Guidance League (Gukmin Bodo Yeonmaeng, 국민보도연맹), a “rehabilitation” program that became the basis for preventive arrests and killings as the war broke out.Yi Seung-man (Syngman Rhee) · 이승만 · 4:15South Korea’s first president (1948–1960). Note the dual spelling: Yi Seung-man is the scholarly romanization of his Korean name; Syngman Rhee is the English name he used internationally. His government oversaw the Bodo League–related mass killings of suspected leftists by state, police, and army.Nogeun-ri yangmin haksal sageon · 노근리 양민 학살 사건 (No Gun Ri massacre) · 5:23The massacre of civilians at No Gun Ri (July 1950), in which U.S. troops fired on refugees near a railway underpass—now a touchstone for civilian vulnerability and wartime panic.Seoul Daehakgyo Byeongwon haksal · 서울대학교병원 학살 · 6:40The Seoul National University Hospital massacre (June 28, 1950): patients, staff, and wounded killed during the first North Korean occupation of Seoul; later formally recognized by Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.Jeongjeon · 정전 · 12:31Armistice—a cease-fire that stops the shooting but doesn’t end the war. Korea has an armistice (1953), not a peace treaty.Jongjeon / Pyeonghwa hyeopjeong · 종전 / 평화협정 · 12:33End of war / peace treaty—the legal termination of war. Korea never signed one, which is why the past keeps leaking into the present. Get full access to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time at yoonjiwon.substack.com/subscribe