Discover Extra Credit Podcast

Extra Credit Podcast

Extra Credit Podcast

Author: Cameron Combs

Subscribed: 0Played: 7Subscribe

Share

© Cameron Combs

Description

Midweek Bible study at Colonial Heights Church.

Artwork by Scott Erickson (scottericksonart.com)

cameroncombs.substack.com

Artwork by Scott Erickson (scottericksonart.com)

cameroncombs.substack.com

105 Episodes

Reverse

What relationship is the church to have with the world? Many versions of Christianity assume that the church and world are locked in a metaphysical fight to the death. One will win, the other will lose. But the church is not in a competition or duel with the world. Jesus says he will build his church and the gates of hell will not prevail against it. The only competitive relationship the church has is with the powers of hell. “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son…” God is for the world. God loves the world so much he created the church. The fundamental posture of the church is a being-for-the-world rather than a being-against-the-world. The first is intercessory, the latter is competitive. This way of framing the issue is something I learned from Dietrich Bonhoeffer. We’ve spent quite a lot of time with Bonhoeffer’s thought recently. But this is good and right because last Wednesday—February 4—was his 120th birthday! We did not properly celebrate last week (though I’m sure you all celebrated privately). So, in honor of Bonhoeffer’s birthday, we spent time with his lecture notes on 1 Timothy 2:1—7. Here’s the text from 1 Timothy: 1 I urge, then, first of all, that petitions, prayers, intercession and thanksgiving be made for all people— 2 for kings and all those in authority, that we may live peaceful and quiet lives in all godliness and dignity. 3 This is good, and pleases God our Savior, 4 who wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth. 5 For there is one God and one mediator between God and human beings, the human being Christ Jesus, 6 who gave himself as a ransom for all people. This has now been witnessed to at the proper time. 7 And for this purpose I was appointed a herald and an apostle—I am telling the truth, I am not lying—and a true and faithful teacher of the Gentiles.Bonhoeffer’s notes on 1 & 2 Timothy come from a class he taught in the summer of 1938. The lecture notes are handwritten and titled, “Exercises in the Pastoral Epistles.” Here are his notes on 1 Timothy 2…Verse 1. Once Timothy is exhorted toward true teaching, Paul speaks of prayer. It is a deeply rooted predicament of the church-community that it repeatedly forgets that the privilege of prayer has been given not only for its own sake but for the sake of the entire world. “Christ came into the world…” (1:15). That the church-community is rescued from the world does not mean that it should despise the world; instead, it means that its task is to intercede for the world. Precisely because those who have been rescued from the reign of the world truly know the world (“all people”), they are bound with the world in a new manner. Prayer and the preaching of the gospel serve the world according to the will of God in Jesus Christ. The church-community that denies its responsibility toward the world, toward “all people” (v. 1), and withdraws into itself denies the gospel and its commission. The church-community of saved sinners must moreover learn that from now on its prayer cannot be limited to petitions concerning its own affairs, but that genuine prayer extends far beyond that. 1. Petitions—in the beginning, this is the proper attitude of the child. 2. Worship, whose gaze is not upon our own needs but on God’s majesty and glory. 3. Intercession—entreating for other, by right of the church-community’s priesthood. 4. Thanksgiving for everything. In this fullness, congregational prayer belongs to all people, without any privilege for the pious over the unbelievers, friends and enemies. How could the church-community of Jesus ever withhold prayer from the enemies who need it in a special way? In the church-community’s prayer, all that is human becomes one, without distinctions, one before the grace of God. The fact that the church-community should and can see every person, whether powerful or despised, as in need of God’s grace makes it completely free and fearless in its encounter with people and takes away any contempt for humankind and all hatred. Because I am “to pray for all people,” I therefore cannot despise or hate any person; [otherwise] my prayer is a lie. Only in this way does the church-community remain what it is, a church-community of sinners saved by God’s grace.Because all humankind needs the prayer of the church-community, this holds true for kings and those in power as well. As human beings they are the objects of intercession. Whether they are Christians [or] persecutors (Nero), they are human beings, poor sinners in need of salvation and grace. Here, too, Paul always sees the human being behind the office. The church-community should bring petition, worship, intercession, thanksgiving for all people before God, even for enemies! That authorities must be mentioned in particular is necessitated by the fact that the church-community tends to despise and condemn those in power, especially in times of oppression. But this holds true, even for authorities: Petition = that is, for true order and government, justice and truth. Worship = that is, despite enemies and despite the powers that be, do not forget the one who alone has power. Intercession = that is, to ask for salvation and grace for those who are in sin, whose conversion would mean much for many people. Thanksgiving = that is, for the order and power that remains, as well as for the attack of the enemy under which the faith of the church-community endures. The church-community is not particularly called to pray for political-worldly objectives. Rather, the aim of this prayer also serves the church-community. The final objective cannot be that the world should remain in its worldly nature and be happy; the aim of God in the world is always God’s church-community. That which is done by God on earth is done ultimately for the sake of the church-community of Jesus Christ. The church-community, for its part, does everything to win the world for salvation, and that means nothing other than to serve God. But it is able to do this only when it leads a “quiet and peaceable life, in all piety and dignity” (The love of God and neighbor?). The church-community asks not for turbulent times of battle but for quiet and rest. Undoubtedly, God may bless even times of battle, but these are also times of temptation that the church-community does not ask for, for it knows how many fall by the wayside in such times and how difficult the ministry of true piety and dignity is in such times. So much prayer gets lost here, prayer for the oppressors becomes hard for the church-community, and much danger lies in this shortcoming! In a time of chaos the orders of the Christian life dissolve; the temptation to disorder and the frenzy of battle become so grave, shattering the measure of [reverence, respectfulness) and inflicting harm on the church-community.Verse 3. Such prayer for all people is pleasing to God, since God’s salvatory will embraces all people. From this it becomes clear that the content of prayer is the salvation of all people, including kings and authorities. The church-community asks for salvation and knowledge of the truth for all people, that is, for conversion. Verses 5ff. God’s salvatory will is unlimited; no person should be privileged over another person, for they are all human beings, and God is the one and only God, who is above everyone, to whom everyone must be converted. Therefore, pray for all people because they have the same God as you, even if they practice idolatry. There is only one mediator between God and human beings (!) who is there for everyone and who alone is able to save, the human being (!) Jesus Christ. He has given himself for all to be saved and has instituted the preaching of this. Now is the time of proclamation. The apostle has become the teacher for the nations. The universal preaching of salvation corresponds to the universal prayer of the church-community.This needs to be said in particular (against the genealogists who break open the differences among people,) against the teachers of the law who desire to erect boundaries between the pious and sinners, and who claim for themselves a privilege with God. The gospel belongs to all people because it belongs to sinners. How and if the universal salvific will of God will be achieved is no longer the objective of proclamation. Unaffected by this secret (which can easily lead again into “controversies, debates”), proclamation is to be issued universally, preaching law and judgment to those who transgress and the gospel to sinners. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

Pillars That Make Shared Life PossibleWe are moving outward in concentric circles from the center of the church (the eucharist), to ordained ministry, to sociality within the church mediated by Christ, and now to the structures of authority within the church.Talking about power and authority is messy business. People get hurt in church—sometimes inadvertently, other times deliberately. But I’m convinced that the most dangerous thing to do is avoid talking about it. We are in desperate need of different ways of thinking and talking about authority within the church to help us recover a healthy understanding of authority.In 1 Timothy 3:14—15 Paul says that the church is the pillar and support of the truth in the world. Pillars are precisely about structure. They bear the weight of the building so that there is room inside for common life.When we hear the word “authority” we immediately think of someone exerting control over others. Our minds move quickly to abuses of power and how to prevent it. Of course this is important to consider, but it’s not a helpful starting point for reflection. It’s like being inside a building and only able to think about how the whole building might collapse at any moment. That’s going to create unnecessary anxiety and paralyze you from actually getting on with life.The place to start is with Jesus. How does God’s authority and power work according to him? In Mark 10 James and John come to Jesus and ask him if they can have the seats at his right and left hand when he comes in his kingdom. They are asking for positions of power and authority. Jesus tells them that these positions are already appointed. But when the other disciples hear about this they become indignant. So, Jesus calls them all together and says, “The rulers of the gentiles lord it over them, but not so among you. Whoever wants to become great among you must be one who serves. And whoever wants to be first must be the slave of all. For the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve and give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:35—45).True authority, according to Jesus, is authority that serves. Jesus’ authority empowers others, lifts them up, and makes shared life possible. Just like pillars, those with authority are supposed to provide structure to the building, bearing the weight—the responsibility. The way the power of the world works is to make those beneath you bear the weight. “Lording it over” others is a way to exert authority so that they will be the pillars that make your life of luxury possible (think of Pharaoh).The difference between Jesus’ way and the world’s way is seen in who bears the weight? Who acts as the pillars? In the church it should be those with the greatest amount of power who bear the most weight (i.e. the elders, bishops/overseers, pastors/priests, deacons, etc.).One other thing to notice in Mark 10. When James and John ask if they can sit in the positions of power in Jesus’ kingdom, Jesus does not say, “Oh those don’t exist in my kingdom.” He doesn’t say, “Well, it’s actually a round table.” He doesn’t say, “There actually is no way to be great in the kingdom.” Rather, he says that if you want to become great you must do it this way: you must become a servant. Jesus doesn’t say, “Oh I’m not Lord!” Rather, he says, “I am the Lord, as one who serves.” Jesus does not reject authority structures, but he forces us to reshape and reimagine them in the way of the cross.The Question of HierarchyThere is a right and wrong way to hear this. These authority structures in church are often understood as a sort of “religious hierarchy” where the bishops, pastors/priests, deacons, etc. have greater access to God and his presence because they are closer to the top of the hierarchy. The assumption is that there is a fullness at the top of the hierarchy that gets lesser and lesser as you move down. In this (mis)understanding God is located at the top, so the higher up you are the closer to God you are. And the power of God flows first to those at the top of the hierarchy and then down from there like spiritual trickle-down economics. We have to reject this. The economy of God is infinitely better than Reagonomics. The economy of God is founded on the infinite, inexhaustible, and unfathomable riches in Christ Jesus. If we’ve really met God in the face of Jesus Christ then we know that he does not simply occupy the top of the hierarchy, but that in Christ he has also become the servant of all—bending down to humanity to wash feet.The deep theological truth here is that God is not just another being among others on the hierarchy of being. Rather, he is Being itself. He is the one who is creating and sustaining the entire hierarchy. He undergirds it all and gives being to it all. And, as we see in Christ, he means to fill all things on the hierarchy with himself. He is making the whole hierarchy to be himself because in the end Christ will be all and in all.In this understanding, no one is closer to God and his power than anyone else. God is the Source of Life of all he has made.Christ is fully present at all points on the hierarchy. But this does not create a bland, barren, cookie-cutter equality where everything becomes identical and loses its uniqueness. Christ means to fill all things with himself in order to make them uniquely what he’s called them to be so that they can play their unique part. It may be more helpful for us if we flip the picture on its side. Rather than thinking of the hierarchy as a ladder stretching up and down vertically, picture it as the keyboard of a piano stretching horizontally. A piano has higher and lower notes, but none of the notes are more important than the others. All the notes are unique and have their part to play making music.The first notes played in a song don’t have more of the song in it. They clue you in to what song is being played because they “lead” or “initiate” the song, but they themselves are not the whole song. We do need some to be leaders—to “initiate,” to “go first”—simply so that the whole song can be played. Order and structure are unavoidable in music. You can’t play all the notes of the song and sing all the words all at once. It is no different with our shared life in the church. The question is not whether power, authority, and structure will happen in the church, but whether or not it is done faithfully to the Lord who is a Servant. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

Perhaps the most famous line in either First or Second Timothy comes in 1 Timothy 2:5, “There is one God, and so there is one mediator between God and man, namely the man Jesus Christ.”We can easily see the importance of this line, but when we consider it within the context of Paul’s letter to Timothy it can be hard to see how it fits in with the rest of the argument. Yes, Christ is our mediator with God. He has reconciled us to God. He has made peace between us and God. Important? Yes. But is it central? Paul’s letters are his instruction to Timothy on how to handle human relationships within the church. Paul puts it bluntly in 1 Timothy 3:15 “[I am writing this to you] so that you may know how one ought to behave in the household of God, which is the church.”What does Christ as the one mediator between God and humanity have to do with how we conduct ourselves in church? As it turns out, this little line is the heart of all of Paul’s instructions to Timothy. The key is to see that Christ’s mediation is not only vertical (me and God) but also horizontal (me and you).Think of 1 John 4 says about the relationship of the “vertical” and “horizontal”: “If anyone says, “I love God,” and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen cannot love God whom he has not seen” (1 John 4:20). There is no vertical dimension of Christ’s mediation without the horizontal dimension. T.F. Torrance was the first theologian to help me begin to think through what it means to say that Jesus is the one mediator between God and humanity. Torrance calls it “the double movement” of the incarnation: Jesus is (1) God to us and (2) us to God. But it was Dietrich Bonhoeffer who helped me think through the horizontal dimension of Christ’s mediation. In Life Together he begins by contrasting two different kinds communities, or two different ways of relating to others. There is the Self-centered relationship/community (marked by what he calls “Human/Emotional Love”) and the Christ-Centered relationship/community (marked by “Spiritual Love”). This is the passage from Life Together we discussed in class:“Christian community means community through Jesus Christ and in Jesus Christ…We belong to one another only through and in Jesus Christ.”“Among human beings there is strife. ‘He is our peace’ (Eph. 2:14), says Paul of Jesus Christ. In him, broken and divided humanity has become one. Without Christ there is discord between God and humanity and between one human being and another. Christ has become the mediator who has made peace with God and peace among human beings. Without Christ we would not know God; we could neither call on God nor come to God. But without Christ we also would not know our brother, nor could we come to him. The way to them is blocked by our own ego. Christ opened up the way to God and to our brother one another. Now Christians can live with each other in peace; they can love and serve one another; they can become one. But they can continue to do so only through Jesus Christ. Only in Jesus Christ are we one; only through him are we bound together. He remains the one and only mediator throughout eternity.”“In the self-centered community there exists a profound, elemental emotional desire for…immediate contact with other human souls…This desire of the human soul seeks the complete intimate fusion of I and You…in forcing the other into one’s own sphere of power and influence.”“Self-centered love loves the other for the sake of itself; spiritual love loves the other for the sake of Christ. That is why self-centered love seeks direct contact with other persons. It loves them, not as free persons, but as those whom it binds to itself. It wants to do everything it can to win and conquer; it puts pressure on the other person. It desires to be irresistible, to dominate.”“Spiritual love, however, comes from Jesus Christ; it serves him alone. It knows that it has no direct access to other persons. Christ stands between me and others. I do not know in advance what love of others means on the basis of the general idea of love that grows out of my emotional desires. All this may instead be hatred and the worst kind of selfishness in the eyes of Christ…Contrary to all my own opinions and convictions, Jesus Christ will tell me what love for my brothers and sisters really looks like.”“Because Christ stands between me and an other, I must not long for unmediated community with that person. As only Christ was able to speak to me in such a way that I was helped, so others too can only be helped by Christ alone. However, this means that I must release others from all my attempts to control, coerce, and dominate them with my love. In their freedom from me, other persons want to be loved for who they are, as those for whom Christ became a human being, died, and rose again, as those for whom Christ won the forgiveness of sins and prepare eternal life…I must allow them the freedom to be Christ’s. They should encounter me only as the persons that they already are for Christ [or: I must meet the other only as the person that he already is in Christ’s eyes]. This is the meaning of the claim that we can encounter others only through the mediation of Christ. Self-centered love constructs its own image of other persons, about what they are and what they should become. It takes the life of the other person into its own hands. Spiritual love recognizes the true image of the other person as seen from the perspective of Jesus Christ. It is the image Jesus Christ has formed and wants to form in all people.”“[Spiritual love] will not seek to agitate another by exerting all too personal, direct influence or by crudely interfering in one’s life…It will be willing to release others again so that Christ may deal with them. It will respect the other as the boundary that Christ establishes between us; and it will find full community with the other in the Christ who alone binds us together. This spiritual love will thus speak to Christ about the other Christian more than to the other Christian about Christ. It knows that the most direct way to others is always through prayer to Christ.”The question for us is whether we will allow Christ to mediate our relationships—not only with our enemies, but also with those closest to us. Will we seek direct and unmediated contact with them or will we trust them to Jesus’ hands? Will we grow impatient with them or trust them to Jesus’ timing? Are we so invested in our ideas of what we want them to be that we cannot release them to Jesus and allow him to make them what he’s called them to be? Will we interrupt his work in their lives by crudely interfering or will we give Jesus the space to shape and form them?Only when we allow Jesus to mediate our relationships with others will we ever really know them because he is their life This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

In 1 Timothy 4 Paul reminds Timothy that he was commissions into ministry “by Spirit-filled utterance [prophecy] and with the laying on of hands by the council of elders.” Again in 2 Timothy 1 Paul encourages Timothy to “fan into flame the gift of God, which is in you through the laying on of my hands.”This is the beginning of the sacramental ritual of ordination. This ritual is “sacramental” because it not only authorized Timothy for his particular ministerial responsibilities but it also granted the very gift of the Spirit needed to fulfill those responsibilities.A “sacrament” is a sign that accomplishes what it signifies. The Lord’s Supper is a sign of our communion with God through Christ, but it is not merely a sign. When we partake in the Supper the reality of our communion with God is actually taking place. In other words, Jesus is really present in the bread and the cup. This is how the earliest Pentecostal fathers and mothers viewed Communion. In the Communion meal we are not just remembering the past event of Jesus’ death that took place two centuries ago. Rather, as we partake of this meal Christ really communes with us. He is mysteriously present as the Savior, Healer, Spirit-Baptizer, and soon-coming King.Chris Green provides tons of historical examples in his book Pentecostal Theology of the Lord’s Supper. I’ll include just a few of my favorites here.D.W. Kerr (General Council, 1916)The [Weekly Evangel] report of the 1916 General Council of the Assemblies of God includes a lengthy treatment of a sermon preached by D.W. Kerr in preparation for the Communion celebration that closed the meeting. Repeatedly, the article—recounting Kerr’s remarks—emphasizes the present-tense effectiveness of the Supper.‘This meal is intended not only for our spiritual, but for our physical benefit. Here is good news for the sick. You are invited to a meal for your health. As you are eating in faith you can receive healing for your body. If you cannot use the past tense and say ‘By His stripes ye were healed’, turn it into the present tense and declare, ‘By His stripes I am healed’. You say perhaps ‘I hope to be healed’. What time in the future will you be healed? God brings the future down to the present tense.’…[Kerr says] the feast points both back, to Christ’s death, and forward, to his return. However, participants’ focus must remain always on the Supper’s ‘distinct present aspect’…‘Here is the present tense of Calvary. We have come to a place of freshness, the result of Calvary. What is it? Life and life more abundant!…There is nothing old or stale about this memorial feast, the fruit of the vine is not old, the shed blood is not aged, the bread is not stale, the Lord’s body is not a mere thing of the past, the way is new and living. The thing most striking about the character of the feast is its presentness, not its pastness or its futureness. It has a present aspect, there is a sign of warmth, the blood is not cold and coagulated but flowing fresh from the wounded side of Jesus, ‘recently killed and yet living’.Myer Pearlman (Pentecostal Evangel, 1934)“[The meal] consists of the religious partaking of bread and wine, which, after having been presented to God the Father in memorial of Christ’s inexhaustible sacrifice, becomes a means of grace whereby we are inspired to an increased faith and faithfulness to Him who loved us and redeemed us.”E.N. Bell (Weekly Evangel, 1916)In response to a reader’s question about the possible benefits of taking the Supper, sometime editor and frequent contributor E.N. Bell provides a detailed explanation of his view of the Sacrament, complete with a brief overview of four historical positions. Catholics, he says, believe that the bread when it is blessed by the priest is ‘transmuted into the literal living body of Christ’, so that ‘in partaking we actually eat the body of Christ and literally drink His blood, and so get eternal life by partaking of the supper.’ Bell rejects this teaching. He rejects the doctrine of consubstantiation, as well, which he attributes to the Episcopalians. The third position, proposed by ‘the noted theologian Zwingle’ [sic], understands Communion as ‘simply a Memorial Feast,’ in which ‘the only good received in partaking [is] in bringing vividly to memory the truths of Christ’s atoning death.’ In this view, as Bell understands it, neither Christ’s body nor his blood are present at the Table, but are only ‘remembered and appropriated.’ Bell acknowledges some truth in this position, but he finally rejects it, too: ‘It lowers our view of the Lord’s Supper and makes it a thing too common.’ The fourth stance Bell attributes to Calvinists, especially Presbyterians, who maintain, he says, that the elements remain unchanged, but Christ is truly, spiritually present to the celebrants. Having provided this overview, Bell ventures his own view:“There is a good deal of truth in this spiritual view. In fact there is some truth in nearly every view of it. But I do not believe the physical Christ is present in the bread nor in the cup. I believe the loaf is still real bread and the cup still only the fruit of the vine. I believe it is a memorial, for Jesus said, ‘This do in MEMORY of me.’ But it is more than a memorial feast. Jesus is there in the Spirit to bless, quicken, uplift and heal; but what benefit the partaker will receive depends on his spiritual discernment; his faith and his appropriation from the spiritually present living Christ.”Elizabeth Sisson ("Our Health, His Wealth,” 1925)“Ah! Not more truly in that hour, happily called ‘Holy Communion,’ in that service, blessedly named ‘the Lord’s Supper,’ are the emblems of the Saviour’s broken body and shed blood, passed around, than is the SUBSTANCE always being passed to us. ‘You may feast at Jesus’ table all the time.”…She insists that what is needed is “Sacramental living; for it makes continually holy, common things.”Recovery of “sacramental living” is key, I think, to the work God has called us to do in participating in building Christ’s church. “Sacramental living” as Sisson says, makes everyday, humdrum life holy. This is what God means for us. He does not intend for us to live life always waiting on the next wild experience, but for our lives to be integrated sacramentally into his life. God means to sanctifying all aspects of our lives and to fill all things up with the life of his Son. The sacraments teach us that, even though it is harder to track, most of God’s work is in the mundane. As a sacrament the Lord’s Supper trains our vision: Jesus Christ is really present in this ordinary meal of bread and wine. And what is revealed in this meal is the essence of every meal. God means for every meal to become communion with him and our neighbors. The sacrament of ordination (laying on of hands) trains us to see that in the calling of minsters, God is revealing the “priestly essence” of all callings. Every vocation is to be “priestly” at its heart. Done in service and love for the life of the world. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

Paul writes to his young protégé Timothy to “command certain people not to teach false doctrines any longer.” Paul does not ever clearly explain what these false teachers were teaching (Timothy doesn’t need him to). Throughout the two letters we primarily get little hints and insights into the situation by the way Paul talks about the effect these teachings have in the church-community.However, there are two passages in which we get a bit more of the picture regarding the content of the false teaching. In 2 Timothy 2 we learn that they are teaching that the resurrection has already happened, and then in 1 Timothy 4 we hear that they are a “pro-abstinence” group. They teach that people should abstain from marriage (sex) and from certain food (diet).This is almost certainly grounded in some brand of gnostic teaching that asserts that the material creation is corrupt and will spiritually pollute you if you partake in it.Paul strongly refutes this in 1 Tim. 4:3—5:3 They forbid people to marry and order them to abstain from certain foods,which God created to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and who know the truth. 4 For everything God created is good, and nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving, 5 because it is consecrated by the word of God and prayer.The problem was not so much that this heresy was technically imprecise, but that it led to sick living. In fact, it distorts the very heart of what it means to be human. Paul reminds Timothy that everything God created is good (Genesis 1) and has been given as a gift to be received with thanksgiving. The word Paul uses for “thanksgiving” is eucharistia. This, of course, quickly became the language the church used to refer to the Lord’s Supper. In Comunnion we receive with thanksgiving the gift of Christ’s body and blood.Paul says that everything God has created is good and it is consecrated when we receive it with thanksgiving—not because our thanksgiving magically changes the nature of things. Our prayers of thanksgiving are not a hocus pocus spell that magically make unclean things clean. Rather, as Luke Timothy Johnson says, our thanksgiving blesses God by recognizing that all things came from him and that all things are to be returned to him. Without the human thanksgiving the world still belongs to God, but it is not made “known” that it belongs to God. Without our thanksgiving (eucharist) there is no mutuality or reciprocity between the creation and the Creator—there is no relationship.The business of thanksgiving, of eucharist, is priestly work and so it is human work. All humanity is called to be priests, recognizing the goodness of God in all of creation and offering it back to him in thanksgiving and praise. No one has made this case more poignantly than Alexander Schmemann in For the Life of the World:To be sure, man is not the only hungry being. All that exists lives by ‘eating.’ The whole creation depends on food. But the unique position of man in the universe is that he alone is to bless God for the food and the life he receives from Him. He alone is to respond to God’s blessing with his blessing. The significant fact about life in the Garden is that man is to name things. As soon as animals have been created to keep Adam company, God brings them to Adam to see what he will call them…Now, in the Bible a name is infinitely more than a means to distinguish one thing from another. It reveals the very essence of a thing, or rather its essence as God’s gift. To name a thing is to manifest the meaning and value God gave it, to know it as coming from God and to know its place and function within the cosmos created by God.To name a thing, in other words, is to bless God for it and in it…God blessed the world, blessed man, blessed the seventh day (that is, time), and this means that He filled all that exists with His love and goodness, made all this ‘very good.’ So the only natural reaction of man, to whom God gave this blessed and sanctified world, is to bless God in return, to thank Him, to see the world as God sees it and–in this act of gratitude and adoration–to know, name, and possess the world. All rational, spiritual, and other qualities of man, distinguishing him from other creatures, have their focus and ultimate fulfillment in this capacity to bless God, to know, so to speak, the meaning of the thirst and hunger that constitutes life… The first, and basic definition of man is that he is the priest. He stands in the center of the world and unifies it in his act of blessing God, of both receiving the world from God and offering it to God–and by filling the world with this eucharist, he transforms his life, the one that he receives from the world, into life in God, into communion with Him. The world was created as the ‘matter,’ the material of one all-embracing eucharist, and man was created as the priest of this cosmic sacrament.It is not accidental, therefore, that the biblical story of the Fall is centered again on food. Man ate the forbidden fruit. The fruit of that one tree, whatever else it may signify, was unlike every other fruit in the Garden: it was not offered as a gift to man. Not given, not blessed by God, it was food whose eating was condemned to be communion with itself alone, and not with God. It is the image of the world loved for itself, and eating it is the image of life understood as an end in itself.To love is not easy, Mankind has chosen not to return God’s love. Man has loved the world, but as an end in itself and not transparent to God. He has done it so consistently that it has become something that is ‘in the air.’ It seems natural for man to experience the world as opaque, and not shot through with the presence of God. It seems natural not to live a life of thanksgiving for God’s gift of a world. It seems natural not to be eucharistic. The world is a fallen world because it has fallen away from the awareness that God is all in all…Man was to be the priest of a eucharist, offering the world to God, and in this offering he was to receive the gift of life. But in the fallen world man does not have the priestly power to do this. His dependence on the world becomes a closed circuit, and his love is deviated from its true direction. He still loves, he is still hungry. He knows he is dependent on that which is beyond him. But his love and his dependence refer only to the world in itself. He does not know that breathing can be communion with God. He does not realize that to eat can be to receive life from God in more than its physical sense…For ‘the wages of sin is death.’ The life man chose was only the appearance of life. God showed him that he himself had decided to eat bread in a way that would simply return him to the ground from which both he and the bread had been taken. ‘For dust thou art and into dust shalt thou return.’ Man lost the eucharistic life, he lost the life of life itself, the power to transform it into Life. He ceased to be the priest of the world and became its slave.The eucharistic life is what is lost in our world. We ate of the one tree that was not given by God as a gift to us. We ate of the one meal that was not in communion with God. But this is the gospel promise: in Christ God has given us a new meal that restores that communion. It is Christ’s very body and blood. It is the Lord’s supper. It is Eucharist. To eat of it is to be established in the communion of creation with its Creator because Christ, in his very person, is the communion of Creator and creature. As our great High Priest he has restored us to our original vocation as a kingdom of priests called to gather up the world around us and offer it back to him consecrated by our thanksgiving (eucharist) in Christ. In other words, through Jesus Christ creation becomes what it was made to be: very good.Our calling as members of Christ’s body is a priestly calling. It is, as Schmemann says, for the life of the world. Priestly work is work done on behalf of others. We worship, we offer our thanksgiving, for the sake of the world around us. This is the eucharistic life established in Christ. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

“Sound teaching strengthens, while sick teaching weakens…sick teaching leads to sick holiness.” -Dietrich BonhoefferSick Teaching, Sick HolinessGordon Fee argues that the primary purpose of Paul’s Pastoral Epistles is not to establish church order or provide a “church manual” for church governance. Rather, Paul’s purpose in writing to Timothy is to thwart the false teachers that have gained sway in the house churches of Ephesus.Paul can hardly go a chapter without writing about sound teaching/doctrine. The Greek word for “sound” that Paul uses is hygiano. Timothy is to devote himself to hygienic teaching, or teaching that is healthy and leads to health. The false teachers are unaware of the fact that they are promoting what Dietrich Bonhoeffer calls a “sick teaching” that “leads to sick holiness.” In Paul’s words, it is a teaching that “spreads like gangrene” (2 Tim. 2:17).The difficulty is that Paul calls out the problem of sick teaching without really spelling out the nature or the content of such teaching. The reason is obvious. The letter was written to a lifelong companion, who would not have needed such instruction. Timothy is Paul’s “child in the faith” so the entire truth of Paul’s gospel (as we see it in Ephesians, Galatians, and Romans) is taken for granted.We have to pay close attention to see the marks of what Paul considers sick teaching and sick holiness.Marks of Sick TeachingWhat are some of the signs Paul gives to be on alert for to spot sick teaching? How do we spot gangrene?* An addiction to controversy and vain speculations (1 Tim. 1:4)* Legalism/Moral rigorism (1 Tim. 4:3)* Their teaching is driven by fear not motivated by love (1 Tim. 1:7—8, see St. John Chrysostom’s second homily on 1 Timothy)* Conceited (1 Tim. 6:3)* Quarrelsome and argumentative (1 Tim. 6:3)* Abusive/harsh language (1 Tim. 6:3)* An unhealthy attachment to their own opinions (1 Tim. 1:4, 1 Tim. 6:3—5)* Sincere (1 Tim. 4:2)The heart of the difference between sick and healthy teaching is a theme that is never far from Paul’s mind when he mentions these characteristics we’ve just listed. It comes down to freedom, fear, and love.In 2 Tim. 3:6—8 Paul a comparison to the false teachers at Ephesus and two out of the way characters from the book of Exodus. He writes, 6 They are the kind who worm their way into homes and gain control over gullible women, who are loaded down with sins and are swayed by all kinds of evil desires, 7 always learning but never able to come to a knowledge of the truth. 8 Just as Jannes and Jambres opposed Moses, so also these teachers oppose the truth. Jannes and Jambres are names given to two of the magicians in Pharaoh’s court that match Moses blow for blow with magic. Aaron throws his staff on the ground and it turns into a snake, but the magicians can match it. Moses turns the waters into blood, but again Pharaoh’s magicians mimic the sign.In the Old Testament the magicians are not named, but it is a part of the tradition of Jewish midrash to give names to the nameless. By “at least 150 B.C. the Egyptian magicians had been narrowed to two brothers and given the names Jannes and Jambres. By the time of Paul this tradition had become common stock.”This was a battle of power and authority; the authority of Moses, given him by God, and the authority of the magicians. But there is a stark difference in the way the two are wielding this power. Moses used his authority for the sake of liberating the Hebrew people while Jannes and Jambres used their’s to keep the people enslaved.As Chris Green once put it, “How do I know whether I’m speaking so that it’s God’s authority happening or merely my own authority? When I speak with God’s authority you are freed, but when I speak on my authority you are bound to me.”This is the heart of what makes the false teachers teaching so sick: its end goal is enslavement and subjugation to the false teachers. This is not always the easiest thing to discern, but the question has to always be this: is this teaching freeing me or is it dominating me?The Swiss theologian Karl Barth is famous for saying that all of God’s commands are actually permissions, they are “musts” in service of a “may.” And this, Barth says, is what sets God’s command apart from all others: God’s commands are always liberating not enslaving.Think of all God’s creation commands in Genesis 1. “Let there be light” is a command but it is also permission. By the command it permits the light to do what it does. It is a command that gives rise to freedom. God does not dominate, we dominate. God liberates. God doesn’t want slavish obedience, he wants the free obedience of his Son to come out of us in the power of the Spirit.Sick teaching is always driven by fear, the fear of enslavement and domination, and ultimately the fear of death (remember, they are “lovers of money”). But healthy doctrine births love in the hearts of those who hear it because it sets free. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

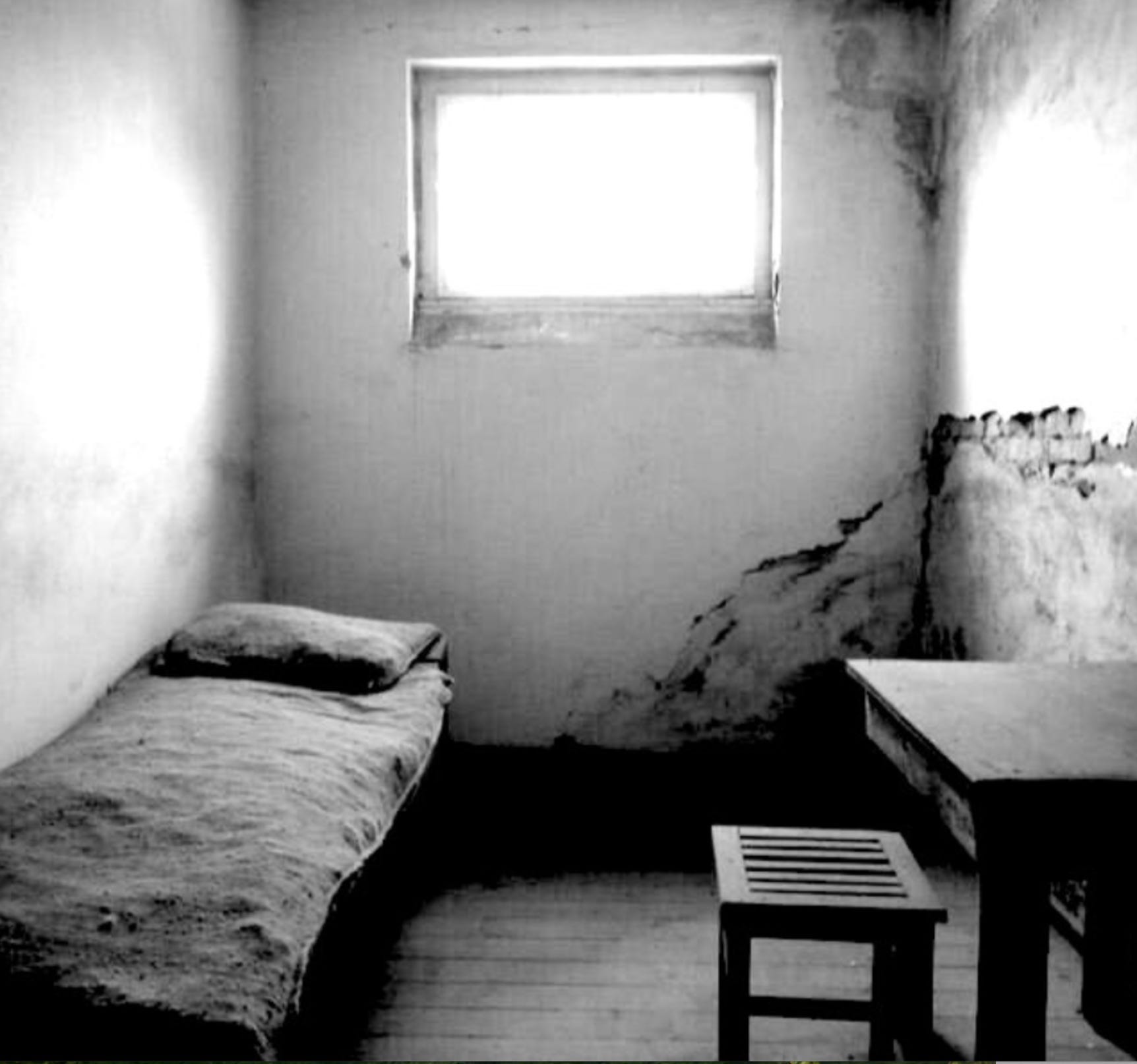

“By the way, a prison cell like this is a good analogy for Advent; one waits, hopes, does this or that—ultimately negligible things—the door is locked and can only be opened from the outside.”-Dietrich BonhoefferThis week we read and discussed some of Bonhoeffer’s letters from prison during the season of Advent. Bonhoeffer touches on themes of suffering, grief, loss, and restoration, and sharing in the sufferings of God. Here are the sections we discussed:Letter to Karl and Paula Bonhoeffer, Dec. 17, 1943My dear Parents,There is probably nothing else for me to do than to write you a Christmas letter just in case. Even though it is beyond comprehension that I may possibly be kept sitting here even over Christmas, nevertheless, in the last eight and a half months I have learned to consider the improbable probable and by a sacrificium intellectus to allow those things to happen to me that I can’t change…Above all, you must not think I will become despondent on account of this lonely Christmas; it will take its distinctive place forever in the series of diverse Christmases I have celebrated in Spain, in America, in England, and I intend that in years to come I will not be ashamed but will be able to look back with a certain pride on these days. That is the one thing no one can take from me…Viewed from a Christian perspective, Christmas in a prison cell can, of course, hardly be considered particularly problematic. Most likely many of those here in this building will celebrate a more meaningful and authentic Christmas than in places where it is celebrated in name only. That misery, sorrow, poverty, loneliness, helplessness, and guilt mean something quite different in the eyes of God than according to human judgment; that God turns toward the very places from which humans turn away; that Christ was born in a stable because there was no room for him in the inn–a prisoner grasps this better than others, and for him this is truly good news. And to the extent he believes it, he knows that he has been placed within the Christian community that goes beyond the scope of all spatial and temporal limits, and the prison walls lose their significance.Letter to Eberhard Bethge, December 18, 1943Dear Eberhard,You too must receive a Christmas letter, at least. I no longer believe I will be released. As I understand it, I would have been acquitted at the hearing on December 17; but the lawyers wanted to take the safer route, and now I will presumably be sitting here for weeks yet, if not months. The past few weeks have been more difficult emotionally than all of what preceded them…I am thinking today above all of the fact that you too will soon be confronting circumstances that will be very hard for you, probably even harder than mine…It’s true that not everything that happens is simply “God’s will.” But in the end nothing happens “apart from God’s will” (Matt. 10:29), that is, in every event, even the most ungodly, there is a way through to God. When, as in your case, someone has just begun an extremely happy marriage and has thanked God for it, then it is exceedingly hard to come to terms with the fact that the same God who has just founded this marriage now already demands of us another period of great privation. In my experience there is no greater torment than longing…I have become acquainted with homesickness a couple of times in my life; there is no worse pain, and in the months here in prison I have had a quite terrible longing a couple of times. And because I think it will be similar for you in the next months, I wanted to write you about my experiences in this. Perhaps they can be of some use for you… Above all, one must never fall prey to self-pity. And finally as pertains to the Christian dimension of the matter, the hymn reads, “that we may not forget / what one so readily forgets, / that this poor earth / is not our home”; it is indeed something important but is nevertheless only the very last thing. I believe we are so to love God in our life and in the good things God gives us and to lay hold of such trust in God that, when the time comes and is here—but truly only then!—we also go to God with love, trust, and joy. But—to say it clearly—that a person in the arms of his wife should long for the hereafter is, to put it mildly, tasteless and in any case is not God’s will. One should find and love God in what God directly gives us; if it pleases God to allow us to enjoy an overwhelming earthly happiness, then one shouldn’t be more pious than God and allow this happiness to be gnawed away through arrogant thoughts and challenges and wild religious fantasy that is never satisfied with what God gives. God will not fail the person who finds his earthly happiness in God and is grateful, in those hours when he is reminded that all earthly things are temporary and that it is good to accustom his heart to eternity and finally the hours will not fail to come in which we can honestly say, “I wish that I were home.” But all this has its time, and the main thing is that we remain in step with God and not keep rushing a few steps ahead, though also not lagging a single step behind either. It is arrogance to want to have everything at once, the happiness of marriage and the cross and the heavenly Jerusalem in which there is no husband and wife. “He has made everything suitable for its time” (Eccl. 3:11). Everything has “its hour”: [”]...to weep and...to laugh;...to embrace and...to refrain from embracing;...to tear and...to sew...and God seeks out what has gone by.” This last verse apparently means that nothing of the past is lost, that God seeks out with us the past that belongs to us to reclaim it. Thus when the longing for something past overtakes us—and this occurs at completely unpredictable times—then we can know that that is only one of the many “hours” that God still has in store for us, and then we should seek out that past again, not by our own effort but with God. Enough of this, I see that I have attempted too much; I actually can’t tell you anything on this subject that you don’t already know yourself.Forth Sunday in AdventWhat I wrote yesterday was not a Christmas letter. Today I must say to you above all how tremendously glad I am that you are able to be home for Christmas! That is good luck; almost no one else will be as fortunate as you. The thought that you are celebrating the fifth Christmas of this war in freedom and with Renate is so reassuring for me and makes me so confident for all that is to come that rejoice in it daily. You will celebrate a very beautiful and joyful day; and after all that has happened to you so far, I believe that it will not be so long before you are again on leave in Berlin, and we will celebrate Easter together once again in peacetime, won’t we?In recent weeks this line has been running through my head over and over: “Calm your hearts, dear friends; / whatever plagues you, / whatever fails you, / I will restore it all.” What does that mean, “I will restore it all”? Nothing is lost; in Christ all things are taken up, preserved, albeit in transfigured form, transparent, clear, liberated from the torment of self-serving demands. Christ brings all this back, indeed, as God intended, without being distorted by sin. The doctrine originating in Eph. 1:10 of the restoration of all things, re-capitulatio (Irenaeus), is a magnificent and consummately consoling thought. The verse “God seeks out what has gone by” is here fulfilled…By the way, “restoration” is, of course, not to be confused with “sublimation”!Letter to Renate and Eberhard Bethge, Christmas Eve 1943Dear Renate and Eberhard,…I want to say a few things for the period of separation now awaiting you. One need not even mention how difficult such separation is for us. But since I have now spent nine months separated from all the people I am attached to, I have some experience about which I would like to write to you. Up to now, Eberhard and I have shared all experiences that were important to us and thereby helped each other in many ways, and now, Renate, you will be part of this in some way. In the process you should attempt somewhat to forget me as “uncle” and think of me more as the friend of your husband. First, there is nothing that can replace the absence of someone dear to us, and one should not even attempt to do so; one must simply persevere and endure it. At first that sounds very hard, but at the same time it is a great comfort, for one remains connected to the other person through the emptiness to the extent it truly remains unfilled. It is wrong to say that God fills the emptiness; God in no way fills it but rather keeps it empty and thus helps us preserve—even if in pain—our authentic communion. Further, the more beautiful and full the memories, the more difficult the separation. But gratitude transforms the torment of memory into peaceful joy. One bears what was beautiful in the past not as a thorn but as a precious gift deep within. One must guard against wallowing in these memories, giving oneself entirely over to them, just as one does not gaze endlessly at a precious gift but only at particular times, and otherwise possesses it only as a hidden treasure of which one is certain. Then a lasting joy and strength radiate from the past. Further, times of separation are not lost and fruitless for common life, or at least not necessarily, but rather in them a quite remarkably strong communion—despite all problems—can develop. Moreover, I have experienced especially here that we can always cope with facts; it is only what we anticipate that is magnified by worry and anxiety beyond all measure. From first awakening until our return to sleep, we must commend and entrust the other person to God wholly and without reserve, and let our worries become prayer for the other person. “With anxieties and with worry...God lets nothing be taken from himself.”Letter to Eberhard Bethge, May 20, 1944Dear Eberhard,This letter is written just t

I.Fleming Rutledge says that “Advent begins in the dark.” She writes, We live in a world where the season of Advent is simply relegated to the “frenzy of holiday” time in which the commercial Christmas music insists that “it’s the most wonderful time of the year” and Starbucks invites everyone to “feel the merry.” The disappointment, brokenness, suffering, and pain that characterize life in this present world is held in dynamic tension with the promise of future glory that is yet to come. In that Advent tension, the church lives its life.Advent is the season in which we take the darkness of the world seriously. In one of his letters from prison Dietrich Bonhoeffer suggests that Advent and a prison cell have a lot in common:By the way, a prison cell like this is a good analogy for Advent; one waits, hopes, does this or that—ultimately negligible things—the door is locked and can only be opened from the outside.It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that we find the central figure of Advent, John the Baptist, in prison in Matthew 11. John has been thrown in prison by King Herod and as he awaits his execution he sends two of his disciples to Jesus to ask him a question: “Are you the one who is to come are should we look for another?” (Matt. 11:3).This is most commonly read today as a moment of doubt for John. It makes easy sense to us. He is suffering in prison for unjust reasons. He is about to be put to death. How could this be happening to him as Jesus is so close by? II.It’s surprising, then, that hardly any of the early church fathers read Matthew 11 like we do. Some (like Tertullian and Justin Martyr) read this passage thinking of John like Peter. Peter confessed that Jesus was the Christ, the Son of the Living God, but then is immediately rebuked by Jesus because he doesn’t think Jesus should suffer in Jerusalem. Peter made the right confession, but didn’t fully understand how Jesus was to be the Messiah. So, some fathers said, John was a pious prophet and acknowledged Jesus and preached the remission of sin, but he could not believe that Christ would have to die and suffer.But that’s the minority report. Most of the fathers saw it differently. They said: What happened to Peter couldn’t have been what happened to John because John was a prophet—yes, even more than a prophet! Jesus couldn’t be clearer when he said that all the prophets testify that he must suffer, be put to death, and rise on the third day. This is the heart of the prophets. John was a prophet and Peter wasn’t. (In fact, Peter didn’t understand any of the prophets until after the resurrection.)John bore witness to Jesus saying, “Behold the lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.” Clearly John knew that Jesus was not going to become the Messiah by military might, but that he would die as a sacrificial lamb.So, why does he send his disciples to ask if Jesus is really the coming one? Is this not a moment of weakness? Church fathers like Gregory the Great, Jerome, and John Chrysostom insist that he was not asking out of his own doubt or ignorance, but because he already knew the answer to the question. Jerome says that John is asking this question in the way Jesus asked the question, “Where is Lazarus buried?” He did not ask because he was ignorant but in order that those who were with him “might be prepared for faith” and believe.In the same way, John asks his question in order that he might prepare the way for his disciples to come to faith in Jesus, the Lamb of God. This is an astounding reading, and one that does not occur to most of us as we read Matthew 11 today. It sounds a bit hard to believe. On this reading, John doesn’t think of his imprisonment as something he must be delivered from, but he sees this as an opportunity for his disciples to come to faith. It sounds absurd until you keep reading the passage. As John’s disciples head back to John, Jesus speaks to the gathered crowd about John. He asks the crowd: “What did you go out into the wilderness to look at? A reed shaken by the wind? What, then, did you go out to see? Someone dressed in soft robes? Look, those who wear soft robes are in royal palaces. What, then, did you go out to see? A prophet? Yes, I tell you, and more than a prophet. (Matt. 11:7—9)If John was a reed shaken by the wind he would be someone who was wavering because of his circumstances. But that’s not John. And, Jesus says, John does not wear soft clothing but camel’s skin, he doesn’t dwell in the king’s house but in the wilderness. John is quite at home in discomfort and suffering.And if John is not only a prophet but more than a prophet, then of course he knows that Jesus is the promised messiah and that he must suffer in order to bring salvation to the world. All the prophets testify to this.John is not sending word to Jesus to ask, “Are you really the one coming one? Are you coming to this prison to set me free or not?” Rather, John’s imprisonment has become the occasion for him to prepare the way for the Advent of Christ into the hearts of his own disciples and for those who hear his question today.I wonder if this reading (which is easily supported by the text) sounds outlandish to us today simply because our faith is not as mature. Put another way, I think very often our readings of scripture tell more about us and our own character than anything else. Perhaps most of us don’t see this possibility in the text because we can’t imagine being this faithful ourselves. As Gregory the Great says, “The sacred scriptures grow with the one who reads them.”(Both Gregory and Jerome actually go on to give an even deeper reading of John the Baptist’s question. They suggest that his question was not only for the sake of his disciples and their faith, but that John was actually asking for another commission from Jesus. Gregory says that John knew at the waters of the Jordan that Jesus was the Redeemer of the world, but now that he is about to die in prison and go into sheol John was asking if he could be the first one to tell the spirits in prison that Jesus is coming. In other words, both Jerome and Gregory suggest that John is saying, “After I die can I be the first one to share the good news in sheol?” That’s a reading that requires a level of faith that is way beyond my capacity to imagine.)III.We return to the theme of Advent. Advent is about the “once and future coming” of Jesus. But speaking of Christ’s “second coming” can be misleading. Of course it isn’t wrong to use this language, but we have to be careful that we not think that it means the Jesus is not here right now.This is why Karl Rahner says that Christ’s “second coming” is really only the fulfillment of his one coming which is still in progress at the present time. The church has spoken of Christ’s Advent in three ways: 1) his advent in the Incarnation (past), 2) his advent in glory (future), but also 3) his advent in and through his Word and the sacraments (present).That’s what Rahner means by saying that Christ really only has one coming which has already begun and will one day be fulfilled—but is also unfolding right now.The mystery of Advent happens at any moment we open ourselves up to it. Through the power of the Holy Spirit you and I are being made to be the hands and feet of Jesus—his body. So, to put it another way, Christ wants to make his Advent to the world around you through you right now.John was called to proclaim the Advent of the Lord. But John not only announced Christ’s initial coming, but he is also called to embody Christ’s advent even in prison.Chris Green points out that it is odd that Jesus commands his followers to visit people who are imprisoned and yet here in Matthew 11 Jesus does not go and visit John in prison. Why doesn’t Jesus just go to visit John himself? Green says, because Jesus is in John in prison. “Whenever you visit the prisoner you do it to me.”Jesus was inside John in prison, which is why John was able to become the Advent of Jesus for the sake of his disciples. Because Jesus was present in John in his suffering, his suffering was turned outward for the good of others. IV.Many of us feel like we are suffering in a sort of prison right now. And it is easy to begin to wonder why Jesus doesn’t come to you in your prison, in your suffering. But what we have to realize is that Jesus is in you in your suffering, turning it for your good and the good of those around you.That doesn’t mean it was God’s will for John to be in prison. God didn’t put you in your prison but he is inside you in your prison and the walls will come tumbling down. That’s the promise of resurrection.But in the waiting he’s filling you with his Spirit for the sake of your neighbor. In the midst of your prison God is making you to be the Advent of Jesus. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

Why, my soul, are you downcast? Why so disturbed within me?Put your hope in God, for I will yet praise him, my Savior and my God. (Psalm 42:5)Psalm 42 is a psalm of hope in the face of despair, but there isn’t a hint of optimism in it. The literary critic Terry Eagleton once said that the optimist is just as bereft of hope as the nihilist—neither has any need of it. In common usage, though, the language of “hope” is on a continuum with optimism, only weaker. Imagine you have plans for a picnic with friends this weekend, but the forecast is predicting a strong chance of rain. You text one of your friends, “Do you think we will still have the picnic?” They respond, “I’m hopeful, but not optimistic.” You would think they were saying, “I’m wishing for it to happen, but I really don’t think it will.” In this usage, hope amounts to something like “wishful thinking” which doesn’t even rise to the level of optimism.But the psalmist is not an optimist, and he is certainly not engaged in any wishful thinking. He’s hopeful.Herbert McCabe defines optimism as the superstitious belief in “inevitable progress.” Everything will naturally work itself out in the end. Bad things are always followed by good things. “Happily ever after” is the arc of the universe.If this psalmist was an optimist, his psalm would’ve sounded something like this: “My tears have been my food day and night and my enemies taunt me, my soul is cast down within me, BUT I’m sure tomorrow things will start looking up.”This psalmist is not optimistic, but he is filled with hope. Optimism is impersonal, but hope is relational. Hope is the belief in a living God you know you can count on, even if you can’t predict what he is up to. His hope is in God. When we talk about “hoping in God” today I think what we often mean is: “I wish my life would go a certain way, and God is the one who can make that happen.” It’s basically optimism with a dash of “God” thrown in. God becomes the mechanism that ensures the outcome we want. But notice that the psalmist does not actually hope for any specific outcome in his life. His hope is only in God. I think we could put it in even stronger language: the psalmist’s hope is not just in the Lord, his hope is the Lord.The prophet Jeremiah says, “Blessed is the man who trusts in the Lord, whose trust is the Lord” (Jer. 17:7). We could use this same formulation for the psalmist, and insert the word “hope.” His hope is in the Lord, but even more than that his hope is the Lord.Your treasure could be in the bank but your treasure isn’t the bank itself. Our way of using the language of hope turns God into the bank that ensures our desires are fulfilled. Of course there isn’t anything wrong with hoping in God for certain outcomes in your life. But there is a difference in hoping in God for favorable outcomes, and trusting God with the entirety of your life. Theologian Karl Rahner distinguishes these two hopes as “mundane hopes” on the one hand and “theological hope” on the other. Mundane hopes are not bad in any way. But they must give way to theological hope, a complete trusting in and desire for the Giver not just the gifts. In one of his sermons Rahner puts it like this:We have many hopes in our lives that fade, and the question arises whether we also have a hope given by God himself that underpins and embraces everything; a hope that does not perish, but lasts through all our other hopes’ undertakings. We have many hopes: for health, for victory over sickness, for success in life, for love and security, for peace in the world, and thousands of other things to which the life impulse reaches out. They are all good in themselves; we also experience repeatedly the fulfillment of these hopes in part and for a period of time. Finally, all these hopes get disappointed. They fade and pass away, whether they have been fulfilled or not; because we are headed toward death, and along this path our hopes are taken away one after another. What then?...Is there just despair at the death of every hope…? Or does there occur then the event of the one and only, but all-encompassing, hope? Christians witness the experience that in the death of all hopes hope can surge up and conquer. Then we have no single thing to hold onto; the one unfathomability embracing all, and called by the true name of God, silently receives us. And when we let ourselves be taken and fall, trusting that this unfathomable mystery is the one blessed homeland, then we experience that we do not have to hold on in order to be held, we do not have to struggle to win…He is himself our hope. God is the one all-encompassing, all-embracing hope that surges up and conquers even in death. The question is whether or not you can let go of your “mundane hopes” and fall into the hope that is God? Can you trust that falling into him is actually the best place to be?Julian of Norwich, the 14th century English anchoress, led a life filled with suffering. She lived through three sieges of the black plague which killed over half of the population in Norwich. She lived through the assassination of a king and an archbishop. She witnessed the nationwide rioting of the poor in the Peasants’ Rebellion and the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France. The world she lived in was, by all accounts, falling apart at the seams. On top of all this she herself almost died from terrible health crisis. And it was in the midst of this sickness that she had 16 visions (or showings) that she later recorded and called Revelations of Divine Love. In the most famous line in her Revelations Jesus said to her:"It is true that sin is the cause of [the pain of the whole world],

but all shall be well,

and all shall be well,

and all manner of thing shall be well."

These words were said most tenderly...

"I am able to make everything well, and

I know how to make everything well, and

I wish to make everything well, and

I shall make everything well..."It seems to me that what happened to Julian in her visions is precisely what Karl Rahner described above. Julian is brought to the brink of death and meets Christ—the one ell-encompassing, all-embracing hope which holds us. She is not told how things shall be well, but only that they shall be well. Her hope is not merely in the Lord, her hope is the Lord. Julian is not optimistic but she is completely hopeful. She experienced in her bones what the psalmist is saying. All shall be well, not because she thinks she will get what she wants in the end, but because in the end she knows the God who holds her in his hands and she trusts him to be her hope.That’s hopeful, but it’s not optimistic. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

The superscription of Psalm 34 contains an oddity. It reads: “A Psalm of David, when he changed his behavior before Abimelech; who drove him away, and he departed.” The account of David “feigning madness” is found in 1 Samuel 21, but in 1 Samuel it is not before Abimelech that David “changed his behavior,” it was before King Achish. So, why has the name been changed in the superscription of Psalm 34? Why Abimelech instead of Achish?For many of us in American evangelical spaces this at least hints at questions of “inerrancy.” Is this a historical error in scripture? In class we took this opportunity to discuss why theories of inerrancy frame the question of scripture’s authority in precisely the wrong way. In short, theories of inerrancy encourage us to spend all our energy trying to prove inerrancy is true rather than reading and studying the scriptures to be formed into Christlikeness. Theories of inerrancy often end up teaching us to read the Bible in order to prove that we are right rather than to be sanctified by the Spirit.Robert Jenson argues that many modern people go at the question of the inspiration of scripture backwards. We have begun with what we think we need from scripture, and then have recruited the Spirit to assure us that our expectations are satisfied. But what we think we need the scriptures to be and what God has actually made them to be are two different things. Scripture is God’s gift to us, but it’s not what we would’ve bought for ourselves if we were shopping at Mardel’s. As with everything in life, God gives us what he knows we actually need, not what we think we want.The easiest example of our (misguided) expectations is historical and scientific accuracy. We think that for the Bible to be true it must be completely accurate in all the things we care about. But instead of thinking that we know what the scriptures need to be, shouldn’t we do it the other way around and ask, “What is the wisdom of the Spirit in giving us these texts?”Jenson writes, “We might even ask what [the Spirit] intends with any errors found in [scripture]… Some of the [early church] Fathers had a theory that may not be so bizarre as it sounds at first: manifest errors and lacunae are there to trip up our penchant for exegetical simplicities.”To put it bluntly: Is the Spirit’s goal to ensure the scriptures are inerrant and scientifically accurate or is his goal to form you into the image of Jesus with them? Jenson points out that the early church Fathers had a much different relationship to “errors” or “oddities” within scripture (although they would never have called them errors). Premodern Christian readers assumed that the “errors/oddities” were all there on purpose. Why? To slow us down. To provoke us to wrestle with a text as Jacob wrestled with God until he was blessed. In class we compared the two approaches: 1) how do people read the superscription of Psalm 34 if they are concerned about upholding inerrancy versus 2) how St. Augustine read it in the fourth century?The contrast is stark. Those who read with the goal of upholding inerrancy inevitably end up explaining away the “oddity” of the text. Augustine sees the oddity as an invitation into the mystery of Christ’s sacrifice of his body and blood. Hopefully you can see my point in all of this. It’s not that there isn’t a way to affirm that the Bible is “inerrant,” it’s just that it isn’t very helpful. To put it cheekily (and overly simplistically): You can either read the scriptures to pile up information or for the sake of your transformation, but you can’t do both.The Spirit’s intention with the scriptures is to speak the living Word (Jesus, himself) to you whoever you are and whatever situation you find yourself in. It’s that particular and personal precisely because Jesus is the Word in the words of scripture. And what the Spirit spoke to Augustine and his church will be different from what the Spirit is speaking to us in our churches this Sunday. And, even more, what he will say to your neighbor sitting in the pew next to you this Sunday will be different than what he is saying to you. That’s just what it means to say Jesus is risen. It seems to me that very often attempts to secure a wooden theory of inerrancy are covert attempts to have the Bible without the resurrected Jesus. It can be an attempt to contain Jesus in the past, and therefore control what he has to say.As I try to stop preaching at you, I’ll leave you with Dietrich Bonhoeffer on the doctrine of the inspiration of scripture (as opposed to a theory of inerrancy):The biblical doctrine of inspiration removes the Bible from the historical situation... Inspiration means that God commits himself to the word spoken by this human being in all its inadequacies. Inspiration [means] that God turns his word back to himself. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

What hard travail God does in death!

He strives in sleep, in our despair,

And all flesh shudders underneath

The nightmare of His sepulcher.

The earth shakes, grinding its deep stone;

All night the cold wind heaves and pries;

Creation strains sinew and bone

Against the dark door where He lies.

The stem bent, pent in seed, grows straight

And stands. Pain breaks in song. Surprising

The merely dead, graves fill with light

Like opened eyes. He rests in rising.

(Wendell Berry, A Timbered Choir: Sabbath Poems)The Gospel of John begins by linking itself to the book of Genesis with its first words, “In the beginning…” The attentive reader will be on high alert for further connections.Like the synoptic Gospels, John has the sabbath controversies between Jesus and the religious leaders play a big role in the narrative. But with John’s strong connection to Genesis we may be able to discern more layers in the controversies. The command to remember the sabbath day finds its grounding in the creation narrative of Genesis. On the seventh day God rested from all his work. And, notoriously, Genesis doesn’t mention any conclusion to this seventh day. God continues to rest. Or, at least, that’s the implication many have taken.John Behr, in his book John the Theologian and his Paschal Gospel, notes that in John 5 Jesus heals a sick man on the sabbath. The religious leaders “started persecuting Jesus, because he was doing such things on the sabbath.” Jesus’ response to them is curious: “My Father is still working, and I also am working” (Jn. 5:17). The Son and the Father are not resting, but still working. Just a few verses later Jesus tells us specifically what the works of his Father are: “The Father raises the dead and gives them life…” (5:21). This is God’s work. And he is still working. The creation week of Genesis 1 is not finished yet.Just as in Genesis, so also in the Gospel of John: God works until the end of the sixth day. And in John it is on the sixth day of the week that Jesus is crucified. In the Genesis creation account it is on the sixth day that God creates human beings as his final work before resting. And now on the sixth day in John’s Gospel Pilate brings Jesus before the crowd and says, “Behold the human being” (ho anthropos; Jn. 19:5).And when the sixth day is nearing its conclusion, Jesus says, “It is finished.” What is finished? The works of God—dying with the dead in order to give life to them. The sixth day of John’s creation week is over. Only now does God rest from his work.Startlingly, this would make the seventh day the day that Jesus’ body lay in the tomb. The deep truth of the sabbath is that it is actually Holy Saturday, when Jesus rests from his work of creation—of giving life to the dead.And, if I can hazard this thought, I don’t think John means to say that the story of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection is the beginning of a new creation or re-creation. But that this is God’s first work of creation. The Father is still working. In John’s telling the sixth day of the first creation week has not concluded yet.To put it another way: the sabbath rest of God that Genesis tells us about is happening right before our eyes in John’s Gospel. Jesus in the tomb is God resting on the seventh day of the creation week.This is the sabbath sleep we are called into. For God to finish his work in us, we are called to rest in the rest of Jesus. To sleep with him so that we may also rise with him. Stop striving. Stop working. Just rest. God’s greatest work begins when you and I sleep (Ps. 127:2). The God who brought Eve out of Adam’s side while he slept; the God who made the covenant with Abraham while he slept; the God who was at work in the sleep of Jesus will do what you and I cannot do.As Wendell Berry says, “What hard travail God does in death! He strives in sleep.”Trust yourself to his work and sleep his sabbath sleep with him. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit cameroncombs.substack.com

Psalm 27

7 “Hear, O LORD, when I cry aloud;

be gracious to me and answer me!

8 “Come,” my heart says, “seek his face!”

Your face, LORD, do I seek.