Discover Cellular and Molecular Biology for Research

Cellular and Molecular Biology for Research

Cellular and Molecular Biology for Research

Author: Ahmadreza Gharaeian

Subscribed: 44Played: 241Subscribe

Share

© Ahmadreza Gharaeian

Description

Cellular and Molecular Biology for Research is the podcast where complex textbooks stop gathering dust and start making sense. Each episode breaks down the dense chapters of cellular and molecular biology—DNA, signaling pathways, protein folding, experimental techniques—into clear explanations for students, early-career researchers, or anyone who wants to actually understand the science instead of just memorizing it. Think of it as your study buddy who reads the heavy stuff, translates the jargon, and hands you the key concepts (with a little less pain and a lot more clarity).

48 Episodes

Reverse

Your thoughts, movements, and moods all depend on chemistry — specifically, the brain’s breathtakingly precise neurotransmitter systems. In this episode, we dive into the molecules that make neurons talk, and the elegant machinery that keeps those conversations going.We’ll revisit the pioneers of neurochemistry, from Otto Loewi, who discovered acetylcholine and proved that neurons communicate with chemicals, to Henry Dale, who gave us the language we still use today — cholinergic, noradrenergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic. Each neurotransmitter system isn’t just a single molecule; it’s an entire operation: the enzymes that make it, the vesicles that store it, the transporters that recycle it, and the receptors that respond to it.From amino acids to amines to peptides, these tiny messengers define how the brain controls everything from muscle contraction to mood regulation. Understanding them is key to unlocking how drugs, disorders, and even our own emotions shape neural activity.Join us as we explore the variety, precision, and beauty of the brain’s chemical code — the systems that turn electricity into emotion, thought into action, and chemistry into consciousness

Your thoughts, movements, and moods all depend on chemistry — specifically, the brain’s breathtakingly precise neurotransmitter systems. In this episode, we dive into the molecules that make neurons talk, and the elegant machinery that keeps those conversations going.We’ll revisit the pioneers of neurochemistry, from Otto Loewi, who discovered acetylcholine and proved that neurons communicate with chemicals, to Henry Dale, who gave us the language we still use today — cholinergic, noradrenergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic. Each neurotransmitter system isn’t just a single molecule; it’s an entire operation: the enzymes that make it, the vesicles that store it, the transporters that recycle it, and the receptors that respond to it.From amino acids to amines to peptides, these tiny messengers define how the brain controls everything from muscle contraction to mood regulation. Understanding them is key to unlocking how drugs, disorders, and even our own emotions shape neural activity.Join us as we explore the variety, precision, and beauty of the brain’s chemical code — the systems that turn electricity into emotion, thought into action, and chemistry into consciousness.

We’ve seen how a thumbtack to the foot can trigger an electrical storm in your nerves — but how does that signal jump from one neuron to the next? Welcome to the synapse, the tiny but mighty junction where information changes hands.In this episode, we trace the story from the late 1800s, when scientists first realized neurons don’t just touch — they communicate. Early researchers like Charles Sherrington gave this mysterious meeting point a name, while others debated whether neurons talked through electricity or chemistry.We’ll follow the experiments that settled the score — from Otto Loewi’s famous frog heart experiment that revealed chemical messengers, to Bernard Katz’s work showing how nerve impulses trigger neurotransmitter release, and John Eccles’ discovery that most brain synapses rely on chemical signaling.Today, we know that synaptic transmission is at the heart of everything the nervous system does — from reflexes to memory, emotions to mental illness.Join us as we unpack how these tiny connections create the grand symphony of the brain: how neurotransmitters are made, stored, and released, and how every signal you think, feel, or remember begins at the space between two neurons.

Your brain speaks in electricity — tiny, rapid bursts called action potentials. In this episode, we break down the signal that carries information through your nervous system at lightning speed. Normally, a neuron’s interior is slightly negative compared to the outside — but when an action potential hits, that balance flips in a split second, and the inside becomes positive.This brief electrical surge, also known as a spike or nerve impulse, races along the axon without losing strength. Every thought, movement, and sensation you have depends on the frequency and pattern of these impulses — the brain’s own version of Morse code.Join us as we explore how neurons generate and send these powerful signals, and how a single pulse of electricity becomes the foundation for everything your nervous system does

Ever wonder what’s happening inside your body when you step on a thumbtack and instantly yank your foot away? In this episode, we dive into the electrifying world of your nervous system — literally. From the first spark of pain at your skin to the lightning-fast signals racing up your spinal cord, we unpack how neurons collect, process, and transmit information.You’ll learn how the brain’s communication lines — neurons — send signals not through copper wires, but through charged atoms called ions, and how they’ve evolved a clever trick called the action potential to keep those signals strong and fast. We’ll also uncover the secret “battery” that powers every thought and movement: the resting membrane potential.Join us as we explore how a tiny voltage difference across a cell’s membrane builds the foundation for everything your brain and body can do — from reflexes to reasoning.

The historical foundations of neuroscience were laid by numerous individuals over many generations. Today, researchers at various levels of analysis and employing diverse technologies are making significant strides in uncovering the brain's functions. The results of these endeavors form the basis of this textbook. The primary aim of neuroscience is to comprehend how nervous systems operate. Valuable insights can often be gained from observing the brain’s activity indirectly. Since behavior reflects brain activity, careful behavioral measurements provide information about the brain's functional capabilities and limitations. Computational models that replicate the brain’s computational properties allow us to explore how such properties emerge. By recording brain waves from the scalp, we can investigate the electrical activity of different brain regions during various behavioral states. Advanced imaging techniques now enable researchers to examine the structure of the living brain in situ, while even more sophisticated methods reveal which brain areas become active under specific conditions. However, despite the advancements in noninvasive methods, these approaches cannot entirely replace direct experimentation with living brain tissue. To interpret remote signals accurately, it is essential to understand how they are generated and their significance. A comprehensive understanding of brain function requires examining its contents—neuroanatomically, neurophysiologically, and neurochemically. The current pace of neuroscience research is remarkable, fueling for new treatments for the many debilitating nervous system disorders affecting millions annually. Yet, despite centuries of progress, including recent decades of advancement, a complete understanding of the brain’s extraordinary abilities remains a distant goal. Nevertheless, this ongoing journey continues to inspire hope and discovery.

Functional genomics focuses on analyzing the expression of numerous genes. One branch of this field is transcriptomics, which examines transcriptomes—all the RNA transcripts produced by an organism at a specific time. A common approach in transcriptomics involves the creation of DNA microarrays or microchips containing thousands of cDNAs or oligonucleotides. These arrays are hybridized with labeled RNAs (or their corresponding cDNAs) from cells, and the hybridization intensity at each spot indicates the expression level of the corresponding gene. This method enables the simultaneous analysis of the timing and location of expression for multiple genes.Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE) identifies which genes are expressed in a particular tissue and measures their expression levels. It works by generating short gene-specific tags from cDNAs, ligating them between linkers, and sequencing the ligated tags to determine gene expression and abundance. Cap Analysis of Gene Expression (CAGE) provides similar data but focuses on the 5'-ends of mRNAs, enabling the identification of transcription start sites and aiding in the localization of promoters.High-density transcriptional mapping of entire chromosomes has revealed that most sequences in cytoplasmic polyadenylated RNAs originate from non-exon regions of ten human chromosomes. Additionally, nearly half of the transcription from these chromosomes is nonpolyadenylated. These findings suggest that the majority of stable nuclear and cytoplasmic transcripts derive from regions outside exons, which may explain significant differences between species, such as humans and chimpanzees, whose exons are nearly identical.

Several approaches are available for identifying genes within a large, unsequenced DNA region. One method is the exon trap, which employs a specialized vector to selectively clone exons. Another involves using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes to locate CpG islands—DNA regions containing unmethylated CpG sequences. Prior to the genomics era, geneticists mapped the Huntington disease gene (HD) to a region near the end of chromosome 4, subsequently using an exon trap to identify the gene itself.Advancements in automated DNA sequencing methods have enabled molecular biologists to determine the base sequences of various organisms, from simple phages and bacteria to yeast, plants, animals, and humans. In the Human Genome Project, much of the mapping work utilized yeast artificial chromosomes (YACs), which are vectors containing a yeast origin of replication, a centromere, and two telomeres. These vectors can accommodate foreign DNA up to 1 million base pairs long, which replicates alongside the YAC. However, due to their superior stability and ease of use, bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) became the preferred tool for sequencing. BACs, derived from the F plasmid of E. coli, can accept DNA inserts up to approximately 300 kilobases, with an average insert size of about 150 kilobases.Mapping large genomes, such as the human genome, requires a set of landmarks (markers) to determine the positions of genes. While genes themselves can serve as markers, most markers consist of anonymous DNA segments like RFLPs, VNTRs, STSs (including ESTs), and microsatellites. Restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) are variations in the lengths of DNA fragments produced by cutting DNA from different individuals with a restriction enzyme, often caused by the presence or absence of specific restriction sites.

Transposable elements, also known as transposons, are DNA segments capable of moving from one location to another within the genome. Some transposable elements replicate during the process, leaving one copy in the original position and inserting a new copy at a different site, while others move without replication, vacating the original site entirely. Bacterial transposons can be categorized as follows: (1) insertion sequences, such as IS1, which consist solely of the genes required for transposition and are flanked by inverted terminal repeats; and (2) transposons like Tn3, which resemble insertion sequences but include at least one additional gene, often conferring antibiotic resistance.Eukaryotic transposons exhibit diverse replication strategies. DNA transposons, such as Ds and Ac in maize or the P elements in Drosophila, function similarly to bacterial DNA transposons like Tn3.The immunoglobulin genes in mammals undergo rearrangement through a mechanism analogous to transposition. Vertebrate immune systems generate immense diversity in immunoglobulin production by assembling genes from two or three components selected from a heterogeneous pool. This process, called V(D)J recombination, relies on recombination signal sequences (RSSs) that include a heptamer and a nonamer separated by either 12-bp or 23-bp spacers. Recombination occurs exclusively between a 12 signal and a 23 signal, ensuring the incorporation of only one of each type of coding region into the assembled gene. Key players in human V(D)J recombination are RAG1 and RAG2, which create single-strand nicks in DNA adjacent to a 12 or 23 signal. This triggers a transesterification reaction where the newly formed 3'-hydroxyl group attacks the opposite strand, leading to a break and forming a hairpin at the end of the coding segment.

Homologous recombination is vital for life. In eukaryotic meiosis, it ensures proper separation of homologous chromosomes by locking them together and promotes genetic diversity in offspring by scrambling parental genes. In all life forms, it plays a crucial role in managing DNA damage. In E. coli, homologous recombination via the RecBCD pathway starts with the invasion of duplex DNA by single-stranded DNA from another duplex that has undergone a double-stranded break. This process begins with RecBCD's nuclease and helicase activities, which generate a free end by preferentially nicking DNA at Chi sites. The invading strand is then coated with RecA and SSB. RecA facilitates the pairing of the invading strand with its complementary homologous DNA, forming a D-loop, while SSB enhances recombination by melting secondary structures and preventing RecA from trapping such structures, which could inhibit subsequent strand exchange. Following this, RecBCD likely nicks the D-loop strand, creating a branched intermediate known as a Holliday junction. The RuvA–RuvB helicase catalyzes branch migration, moving the crossover of the Holliday junction to a favorable resolution site. Finally, RuvC resolves the Holliday junction by nicking two of its strands, producing either noncrossover recombinants with heteroduplex patches or two crossover recombinant DNAs.Meiotic recombination in yeast begins with double-stranded breaks (DSBs) created by two Spo11 molecules. These molecules work together to cleave both DNA strands at closely spaced sites through transesterification reactions involving active site tyrosines. This reaction forms covalent bonds between Spo11 and the newly created DSBs. Spo11 is subsequently released.

Primer synthesis in E. coli involves the primosome, which consists of the DNA helicase DnaB and the primase DnaG. The assembly of the primosome at the origin of replication, oriC, proceeds as follows: DnaA binds to oriC at specific sites known as dnaA boxes and collaborates with RNA polymerase and HU protein to melt a DNA region adjacent to the leftmost dnaA box. Subsequently, DnaB associates with the open complex and promotes the binding of the primase to complete the primosome. The primosome remains attached to the replisome, repeatedly initiating Okazaki fragment synthesis on the lagging strand. Additionally, DnaB exhibits helicase activity, unwinding the DNA as the replisome advances.In the case of the SV40 origin of replication, it is located adjacent to the viral transcription control region. Replication initiation relies on the viral large T antigen, which binds within the 64-bp minimal ori at two adjacent sites. This antigen also possesses helicase activity, creating a replication bubble within the minimal ori. Priming is performed by a primase associated with the host DNA polymerase α.Yeast origins of replication are found within autonomously replicating sequences (ARSs), which consist of four key regions: A, B1, B2, and B3. Region A, a 15-bp sequence, contains an 11-bp consensus sequence that is highly conserved across ARSs. Region B3 may contribute to a critical DNA bend within ARS1.The pol III holoenzyme synthesizes DNA at a rate of approximately 730 nucleotides per second in vitro, slightly slower than the nearly 1000 nucleotides per second observed in vivo. This enzyme is highly processive both in vitro and in vivo. The pol III core (αε or αεθ) alone lacks processivity and can only replicate short DNA segments before dissociating from the template. However, when combined with the β-subunit, the core achieves processive replication at a rate approaching 1000 nucleotides per second. The β-subunit forms a dimer that takes on a ring-like structure, encircling the DNA.

Several principles govern DNA replication across most organisms: (1) Double-stranded DNA replicates in a semiconservative manner, where the parental strands separate and serve as templates for the synthesis of new, complementary strands. (2) DNA replication in E. coli and other organisms is at least semidiscontinuous. One strand, often considered to replicate continuously in the direction of the replication fork's movement, may actually replicate discontinuously. The other strand replicates discontinuously, forming 1–2 kb Okazaki fragments in the opposite direction, allowing both strands to be synthesized in the 5'→3' direction. (3) DNA replication initiation requires a primer. In E. coli, Okazaki fragments are initiated with RNA primers that are 10–12 nucleotides long. (4) Most bacterial and eukaryotic DNAs replicate bidirectionally, though some, like ColE1, replicate unidirectionally.Circular DNAs can replicate via the rolling circle mechanism, where one strand of the double-stranded DNA is nicked, and the 3'-end is extended using the intact strand as a template. This process displaces the 5'-end, and in phage λ, the displaced strand serves as a template for discontinuous, lagging strand synthesis.Pol I is a highly versatile enzyme with three distinct activities: DNA polymerase, 3'→5' exonuclease, and 5'→3' exonuclease. The first two activities reside on a large domain of the enzyme, while the third is on a smaller, separate domain. The large domain, known as the Klenow fragment, can be isolated through mild protease treatment, yielding two protein fragments with all three activities intact. The structure of the Klenow fragment includes a wide cleft for DNA binding, with the polymerase active site located far from the 3'→5' exonuclease active site.Among the three DNA polymerases in E. coli—Pol I, Pol II, and Pol III—only Pol III is essential for replication.

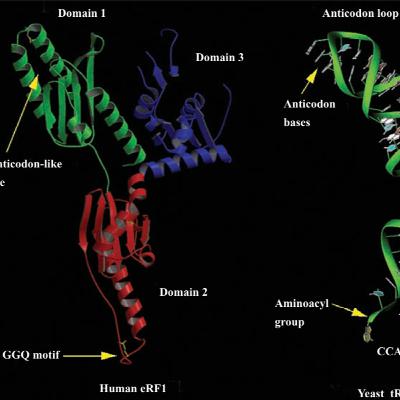

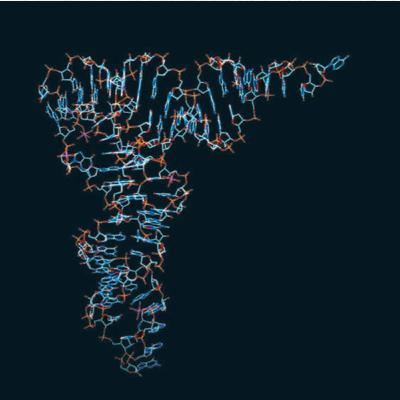

X-ray crystallography studies on bacterial ribosomes with and without tRNAs have revealed that tRNAs occupy the cleft between the two subunits. They interact with the 30S subunit through their anticodon ends and with the 50S subunit through their acceptor stems. The binding sites for tRNAs primarily consist of rRNA. The anticodons of tRNAs in the A and P sites come into close proximity, allowing base-pairing with adjacent codons in the mRNA bound to the 30S subunit, as the mRNA bends 45 degrees between the two codons. The acceptor stems of tRNAs in the A and P sites also approach each other closely—within just 5 Å—within the peptidyl transferase pocket of the 50S subunit, where twelve contacts between ribosomal subunits are visible.The crystal structure of the E. coli ribosome reveals two conformations that differ due to rigid body motions of ribosomal domains relative to each other. Specifically, the head of the 30S particle rotates by 6 degrees and by 12 degrees when compared to the T. thermophilus ribosome. This rotation is likely part of the ratchet-like motion of the ribosome during translocation.The E. coli 30S subunit comprises a 16S rRNA and 21 proteins (S1–S21), while the 50S subunit contains a 5S rRNA, a 23S rRNA, and 34 proteins (L1–L34). Eukaryotic cytoplasmic ribosomes are larger and include more RNAs and proteins than their prokaryotic counterparts. Sequence studies of 16S rRNA proposed its secondary structure (intramolecular base pairing), which has been confirmed by X-ray crystallography studies. These studies reveal a 30S subunit with extensively base-paired 16S rRNA, whose shape essentially defines the particle's overall structure. Additionally, X-ray crystallography studies have identified the locations of most 30S ribosomal proteins.The 30S ribosomal subunit serves two primary roles. It facilitates accurate decoding of mRNA and contributes to the overall function of the ribosome during translation.

Messenger RNAs are read in the 5' to 3' direction, which is the same direction in which are synthesized. Proteins are synthesized from the amino terminus to the carboxyl terminus, meaning the amino-terminal amino acid is added first. The genetic code consists of three-base sequences called codons in mRNA, which instruct the ribosome to incorporate specific amino acids into a polypeptide. The code nonoverlapping, meaning each base is part of only one codon, and it lacks gaps or commas, with every base in the coding region of an mRNA being part of a codon. There are 64 codons in total, three of which are stop signals, while the remaining codons encode amino acids, making the code highly degenerate. The degeneracy of the genetic code is partially managed by isoaccepting tRNA species that bind the same amino acid but recognize different codons. Additionally, wobble pairing allows the third base of a codon to deviate slightly from its normal position, forming non-Watson–Crick base pairs with the anticodon. This enables a single aminoacyl-tRNA to pair with multiple codons. Wobble pairs include G–U (or I–U) and I–A. The genetic code is not strictly universal. In certain eukaryotic nuclei, mitochondria, and at least one bacterium, codons that serve as termination signals in the standard genetic code can instead encode amino acids such as tryptophan and glutamine. In some mitochondrial genomes, the meaning of codons is altered, switching from one amino acid to another. Despite these deviations, the altered codes remain closely related to the standard genetic code from which they likely evolved. Elongation occurs in three steps: (1) EF-Tu, bound with GTP, delivers an aminoacyl-tRNA to the ribosomal A site. (2) Peptidyl transferase forms a peptide bond between the peptide in the P site and the newly arrived aminoacyl-tRNA in the A site, extending the peptide by one amino acid and shifting it to the A site. (3) EF-G, in conjunction with GTP, translocates the growing peptide.

Two critical events precede protein synthesis. First, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases attach amino acids to their respective tRNAs with high specificity through a two-step reaction that begins with the activation of the amino acid using AMP, derived from ATP. Second, ribosomes must dissociate into their subunits at the conclusion of each translation cycle. In bacteria, this dissociation is actively facilitated by RRF and EF-G, while IF3 binds to the free 30S subunit, preventing its reassociation with the 50S subunit to form a complete ribosome.The initiation codon in prokaryotes is typically AUG but can also be GUG or, more rarely, UUG. The initiating aminoacyl-tRNA is N-formyl-methionyl-tRNAfMet. N-formyl-methionine (fMet) is the first amino acid incorporated into a polypeptide chain, although it is often removed during protein maturation. The 30S initiation complex is formed by the association of a free 30S ribosomal subunit with mRNA and fMet-tRNAfMet. This binding depends on base pairing between the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, located just upstream of the initiation codon in mRNA, and a complementary sequence at the 3'-end of the 16S rRNA. IF3 mediates this interaction with the assistance of IF1 and IF2, which are all bound to the 30S subunit at this stage.IF2 plays a central role in promoting the binding of fMet-tRNAfMet to the 30S initiation complex, while the other two initiation factors provide essential support. GTP is required for IF2 binding under physiological IF2 concentrations, though it is not hydrolyzed during this process. The complete 30S initiation complex consists of one 30S ribosomal subunit, one molecule each of mRNA, fMet-tRNAfMet, GTP, IF1, IF2, and IF3. GTP hydrolysis occurs after the 50S subunit joins the 30S complex to form the functional 70S initiation complex.

Ribosomal RNAs are synthesized in the nucleoli of eukaryotic cells as precursors that require processing to yield mature rRNAs. The sequence of RNAs in the precursor is universally 18S, 5.8S, and 28S across all eukaryotes, although the precise sizes of the mature rRNAs differ among species. In human cells, the precursor is 45S, which undergoes a processing scheme that produces 41S, 32S, and 20S intermediates, with snoRNAs playing crucial roles in these steps. Extra nucleotides are removed from the 5'-ends of pre-tRNAs in a single step through endonucleolytic cleavage catalyzed by RNase P. Both bacterial and eukaryotic RNase P enzymes have a catalytic RNA subunit called M1 RNA. In E. coli, RNase II and polynucleotide phosphorylase cooperate to remove most of the additional nucleotides at the 3'-end of a tRNA precursor but halt at the 12-base stage. RNases PH and T are primarily responsible for removing the last two nucleotides. In eukaryotes, a single enzyme, tRNA 3'-processing endoribonuclease (3'-tRNase), performs the processing of the 3'-end of a pre-tRNA.Trypanosome mRNAs are generated through trans-splicing, which links a short leader exon with one of many independent coding exons. In trypanosomatid mitochondria, incomplete mRNAs require editing before translation. Editing occurs in the 3'→5' direction through sequential actions of one or more guide RNAs (gRNAs). These gRNAs bind to unedited mRNA regions, providing A's and G's as templates for inserting missing U's or deleting extra U's.In higher eukaryotes, including fruit flies and mammals, some adenosines in mRNAs must be post-transcriptionally deaminated to inosine for correct translation. This type of RNA editing is performed by enzymes called adenosine deaminases acting on RNAs (ADARs). Additionally, certain cytidines must be deaminated to uridine for accurate mRNA coding. Post-transcriptional gene regulation often involves such modifications to ensure proper gene expression.

Capping occurs in several steps: initially, RNA triphosphatase removes the terminal phosphate from pre-mRNA. Subsequently, guanylyl transferase adds the capping GMP derived from GTP, followed by two methyl transferases that methylate the N7 position of the capping guanosine and the 2'-O-methyl group of the penultimate nucleotide. These processes take place early in transcription, before the RNA chain exceeds 30 nucleotides in length. The cap plays a crucial role in ensuring proper splicing of some pre-mRNAs, facilitating the transport of mature mRNAs out of the nucleus, protecting mRNA from degradation, and enhancing its translatability. Most eukaryotic mRNAs and their precursors possess a poly(A) tail approximately 250 nucleotides long at their 3'-ends, added post-transcriptionally by poly(A) polymerase. The poly(A) tail increases both the stability and translatability of the mRNA, with the relative importance of these effects differing across systems. Transcription of eukaryotic genes beyond the polyadenylation site, after which the transcript is cleaved and polyadenylated at the newly formed 3'-end. An efficient mammalian polyadenylation signal includes an AAUAAA motif about 20 nucleotides upstream of the polyadenylation site, followed 23–24 base pairs later by a GU-rich sequence and then a U-rich motif. Variations in these sequences influence polyadenylation efficiency, with plant signals allowing more flexibility around the AAUAAA motif than animal signals, and yeast signals rarely containing the AAUAAA motif. Polyadenylation involves both cleavage of the pre-mRNA and the addition of the poly(A) tail at the cleavage site. The cleavage process requires multiple proteins, including CPSF, CstF, CF I, CF II, poly(A) polymerase, and the CTD of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II. Among these, CPSF-73 is responsible for cleaving the pre-mRNA.

Nuclear mRNA precursors undergo splicing through a lariat-shaped or branched intermediate. In addition to the consensus sequences at the 5′ and 3′ ends of nuclear introns, branchpoint consensus sequences are also present. In yeast, this sequence is almost invariant as UACUAAC, whereas in higher eukaryotes, the consensus sequence is more variable, represented as YNCURAC. In all cases, the branched nucleotide corresponds to the final A in the sequence. The yeast branchpoint sequence also determines which downstream AG serves as the 3′ splice site.Splicing occurs on a complex structure known as the spliceosome. Yeast and mammalian spliceosomes have sedimentation coefficients of approximately 40S and 60S, respectively. Genetic studies have revealed that base pairing between U1 snRNA and the 5′ splice site an mRNA precursor is necessary but not sufficient for splicing. The U6 snRNP also forms a base-pairing association with the 5′ end of the intron, which begins before the formation of the lariat intermediate but may alter its nature after this initial step. This interaction between U6 and the splicing substrate is critical for the splicing process. Furthermore, U6 interacts with U2 during splicing.The U2 snRNA base-pairs with the conserved sequence at the splicing branchpoint, an interaction essential for splicing. Additionally, U2 forms significant base pairs with U6 to create a region referred to as helix I, which plays a role in aligning these snRNPs for the splicing process. The U4 snRNA base-pairs with U6, contributing to the splicing mechanism.

Eukaryotic DNA associates with basic protein molecules called histones to form nucleosomes. Each nucleosome consists of four pairs of histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) arranged in a wedge-shaped disc, around which 146 base pairs (bp) of DNA are wrapped. Histone H1, which is not part of the core nucleosome, is more easily removed from chromatin than the core histones. In the second level of chromatin folding, both in vitro and presumably in vivo, a string of nucleosomes forms a 30-nanometer (nm) fiber. Studies indicate that this fiber exists in at least two forms within the nucleus: inactive chromatin, characterized by a high nucleosome repeat length (approximately 197 bp), tends to adopt a solenoid folding structure and interacts with histone H1, which stabilizes its structure. Conversely, active chromatin, with a lower nucleosome repeat length (around 167 bp), folds according to the two-start double helical model.The third level of chromatin condensation involves the formation of radial loop structures in eukaryotic chromosomes. The 30-nm fiber forms loops ranging from 35 to 85 kilobases () in length, anchored to the chromosome's central matrix.Core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) assemble nucleosome cores on naked DNA. Transcription of a class II gene in reconstituted chromatin, with an average of one nucleosome core per 200 bp of DNA, shows approximately 75% repression compared to naked DNA. The remaining 25% activity is attributed to promoter sites not covered by nucleosome cores. Histone H1 further represses template activity beyond the core nucleosomes. This repression can be mitigated by transcription factors, some of which, like Sp1 and GAL4, act as both antirepressors (preventing repression by histone H1) and transcription activators. Others, such as the GAGA factor, function solely as antirepressors, likely competing with histone H1 for binding.

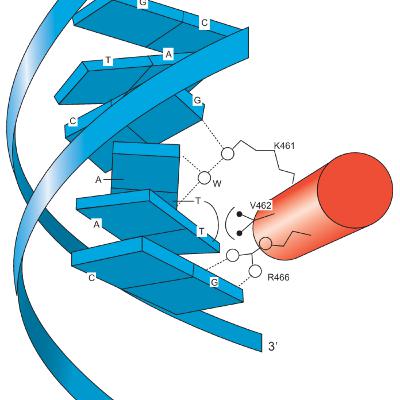

Eukaryotic activators consist of at least two domains: a DNA-binding domain and a transcription-activating domain. DNA-binding domains include motifs such as zinc modules, homeodomains, bZIP, or bHLH motifs. Transcription-activating domains can be acidic, glutamine-rich, or proline-rich. Zinc fingers are characterized by an antiparallel β-sheet followed by an α-helix. The β-sheet contains two cysteines, and the α-helix contains two histidines, which coordinate with a zinc ion to form the finger-shaped structure. This coordination facilitates specific recognition of the DNA target within the major groove.The DNA-binding motif of the GAL4 protein includes six cysteines that coordinate two zinc ions in a bimetal thiolate cluster. This motif features a short α-helix that extends into the DNA major groove, forming specific interactions. Additionally, the GAL4 monomer contains an α-helical dimerization motif that forms a parallel coiled coil with the α-helix of another GAL4 monomer. Type I nuclear receptors are located in the cytoplasm, bound to other proteins. Upon binding their hormone ligands, these receptors release their cytoplasmic partners, translocate to the nucleus, bind to enhancers, and function as activators. A representative example is the glucocorticoid receptor, which contains a DNA-binding domain with two zinc modules. One module provides DNA-binding residues in a recognition α-helix, while the other facilitates protein-protein interactions for dimer formation. These zinc modules use four cysteine residues to complex the zinc ion, unlike classical zinc fingers, which use two cysteines and two histidines.Homeodomains in eukaryotic activators contain a DNA-binding motif that operates similarly to the helix-turn-helix motifs in prokaryotes, where a recognition helix fits into the DNA major groove.