Discover Vices and Volumes | Navigate Irish and British History's Absurdities from 1800s Books

Vices and Volumes | Navigate Irish and British History's Absurdities from 1800s Books

Vices and Volumes | Navigate Irish and British History's Absurdities from 1800s Books

Author: Avril Clinton-Forde

Subscribed: 2Played: 10Subscribe

Share

© Avril Clinton-Forde

Description

Victorians had opinions about EVERYTHING. Jaw shapes. Correct use of coil horns. Servant's gloves. All treated with the kind of earnest detail usually reserved for matters of real importance.

Avril Clinton-Forde selects the delightfully absurd from her collection of Irish and British 1800s books—where privileged people wrote volumes about life's minutiae. Social catastrophes, Irish banshee etiquette, Georgian marriage disasters, bizarre upper-class hobbies, and enjoys wonderfully overcomplicated language of the 19th Century.

For history lovers, heritage enthusiasts, and curious insomniacs!

Avril Clinton-Forde selects the delightfully absurd from her collection of Irish and British 1800s books—where privileged people wrote volumes about life's minutiae. Social catastrophes, Irish banshee etiquette, Georgian marriage disasters, bizarre upper-class hobbies, and enjoys wonderfully overcomplicated language of the 19th Century.

For history lovers, heritage enthusiasts, and curious insomniacs!

13 Episodes

Reverse

In August 1852, Sir Francis Bond Head arrived in post-Famine Dublin and hired a local cabman as his guide. What followed was a tour where historical accuracy took a backseat to the ancient Irish tradition of entertaining visitors—a cultural practice rooted in Brehon Law's requirement to provide travelers with oigidecht: hospitality that included food, shelter, and importantly, entertainment.The cabman's version of history was undeniably creative. Nelson had lost his left arm rather than his right, the statue in College Green depicted "William the Conqueror" rather than William III (six centuries apart), and Dublin's name supposedly derived from "Double-Inn—two houses stuck into one" rather than the Irish Dubh Linn (black pool). Yet his enthusiasm was genuine, his delivery engaging, and his purpose clear: to provide his passenger with an entertaining experience while earning his fare.Head had arrived after a storm-tossed midnight Channel crossing, navigating Morrison's Hotel by single candlelight. By morning, mounted on horseback for observation, he was immediately approached by barefoot boys seeking work—a reminder that Dublin in 1852 was still recovering from the Great Famine. The phrase "I'm wake with the hunger," spoken by an elderly beggar woman, would have carried particular weight just months after the famine's official end.This episode explores Head's observations of Dublin at a transitional moment: the city's exceptional air quality (Phoenix Park's 1,750 acres and Georgian squares provided what Head called "magnificent lungs" compared to coal-choked British industrial cities), the melancholy sight of Daniel O'Connell's empty Merrion Square house still bearing his brass nameplate five years after his death, and the democratic mixing of classes on jaunting cars heading to Donnybrook Fair—soldiers, gentlemen, and working people all sharing the same twopenny ride.Head, a former Royal Engineer who'd fought at Waterloo and served disastrously as Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, brought an engineer's eye to Dublin's architecture and infrastructure. His account captures both the Georgian grandeur and the visible poverty, the political monuments and the human stories, the formal Vice-Regal visits and the street-level encounters that revealed a city's character.What he may not have fully understood was that the cabman's performance wasn't ignorance—it was a cultural tradition of hospitality through storytelling, where entertaining the visitor served both social custom and economic necessity.Features readings from A Fortnight in Ireland (1852) by Sir Francis Bond Head, a source frequently cited by historians studying post-Famine Ireland.

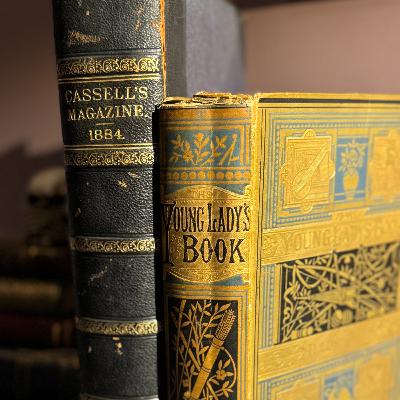

In 1884, Irish born Lady Colin Campbell published articles in Cassell's Family Magazine teaching young women how to become "the perfect lady." Two years later, she'd be in court defending herself in the divorce scandal of the century—her intimate life dissected in newspapers across Britain.This episode explores the impossible standards Lady Colin Campbell outlined for Victorian women: white-headed pins must never project from black dresses, collars must be changed daily, sitting with crossed legs was unforgivable, and women must suppress all natural reactions to absurdity. When a page slips and falls surrounded by dinner rolls, or a cake bowls up the room, a perfect lady neither speaks nor smiles. Even at home, exhausted with children clinging to their skirts, women were expected to maintain "freshness and attractiveness" at all times.But who was the woman behind these rigid rules? Gertrude Elizabeth Blood was born in County Clare, Ireland in 1857 and later educated in Dublin. At 23, she met Lord Colin Campbell and became engaged within three days. What seemed like a fairy tale became a nightmare when her husband infected her with syphilis—a disease he'd concealed before their marriage. In 1886, both parties filed for divorce in a trial so explicit that "intercourse" appeared in newspapers and multiscopes became known as "what the butler saw machines" after the butler's keyhole testimony.The episode contrasts Lady Colin Campbell's advice with the even more demanding standards of Isabella Beeton, whose ideal dinner party featured rented hothouse pineapples, out-of-season fruit, and servants in white kid gloves. The gap between these aspirations and reality trapped women in impossible positions—unable to acknowledge their struggles without admitting social failure.Yet Lady Colin Campbell survived. After social ostracism, she became the first female editor of a London newspaper not exclusively for women, succeeding George Bernard Shaw as art editor of The World. She wrote over 200 articles, became an expert in fencing and fly fishing, exhibited landscape paintings, and earned genuine respect from the brilliant minds of her era. Shaw called her wit "lightning" and her journalism unmatched. She famously called Oscar Wilde "the great white slug."From Cassell's Family Magazine (1884), this episode examines what the pursuit of perfection actually cost Victorian women—and the remarkable resilience required to survive it.

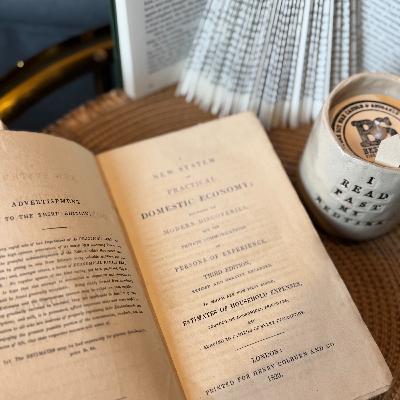

Ever wondered how people survived winter before central heating? Spoiler: they didn't always.This episode takes you inside the Georgian and Victorian bedchamber, where staying warm could literally cost you your life. We're talking about warming pans filled with poisonous fumes, feather beds crawling with insects, and bed curtains so tightly drawn you could suffocate before morning. One household manual even suggested testing this theory with a caged bird at your bedside—which, unsurprisingly, nearly died by dawn.But the Victorians weren't just sitting around freezing. They were innovating. We'll explore the remarkable air-pump mattress of 1823—a proto-waterbed with valves, stop-cocks, and convenient tassels you could pull from your pillow to adjust firmness in the night. Imagine Victorian couples arguing at 3 a.m.: "Stop pulling the tassel, you're making it too firm!"Once you survived the night, you had to get dressed. Victorian winter fashion wasn't just about looking elegant—it was thermal engineering wrapped in seal-skin and given exotic names. We're talking about creations like The Diplomatt (with enormous sleeves and seal-skin trim), The Mexican (black cloth with embroidered white silk), and The Semiramis (named after an Assyrian queen because why not?). These weren't just fashion statements; they were survival gear with marketing departments.And then there's food. Winter soup was serious business, and we'll dive into a heated debate from 1880 about charity soup kitchens. Should soup for the poor contain actual meat, or would that spoil them? One writer insisted that if "starving poor" refused meatless pea soup, they should be "improved morally and physically by being kept without meat." His solution? Pig's head soup so greasy it would "quite equal to mock turtle." Delicious.Through readings from rare books—including my own battered, spineless copy of "A New System of Practical Domestic Economy" (1823)—we'll discover the elaborate rituals, surprising innovations, and occasionally questionable attitudes that defined Victorian winter survival.Features readings from:"A New System of Practical Domestic Economy" (1823, anonymous author)"The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine" (1861)Cassell's Family Magazine: "Winter Soups: How to Make Them" by A.G. Payne (1880)Modern life is easy. We complain about winter from heated homes while wearing fleece and microwaving soup. The Victorians had to earn their warmth through constant vigilance, specialized knowledge, and frankly, a shocking amount of work. This episode is a reminder to appreciate your electric blanket, your North Face jacket, and the fact that your mattress doesn't require a pump with decorative tassels.🎧 New episodes every second week | Follow @vicesandvolumes for daily historical discoveriesKeywords: Victorian history, Georgian era, 19th century, 18th century, vintage books, historical books, winter survival, domestic history, social history, rare books, history podcast, Victorian era, British history, Irish history, period history, household management, historical innovation

What if the two topics you could never, ever mention in polite conversation were yourself and your enemy? Welcome to Victorian feminine conversation, where your tongue was an "unruly member" requiring constant restraint.In this episode, we're diving into Matilda Ann Mackarness 1888 conduct book "The Young Lady's Book," where the chapter on conversation is actually a masterclass in silence. Discover why ladies withdrew to the drawing room after dinner to discuss only servants and babies while gentlemen debated politics and business. Learn which words—awfully, stunning, checky—threatened the very foundations of the English language in the Great Slang Crisis of the 1880s. And meet the young woman so paralyzed by conversational rules that when a gentleman tried engaging her, she could only manage two words in a grave monotone: "So you said."But here's the devastating irony: Matilda Mackarness herself violated every rule she prescribed. Widowed at 43 with seven children and "very slender provision" (Victorian speak for near-poverty), she had to write constantly to survive—producing over 40 books between 1849 and 1881. She couldn't afford to be silent. She couldn't worry whether discussing her hardships was "egotism." She had to speak, loudly and persistently, through every book and periodical she could sell.So why did she teach young ladies to bind their tongues? Was she protecting them? Believing in the rules? Or was she quietly handing over survival strategies for navigating a world where women had no power at all?We'll explore the economics of being "agreeable" (new books cost £150 in today's money), the divine surveillance of idle words ("a heavy reckoning will be demanded"), and why women's speech—like women's bodies—was considered fundamentally unruly and requiring external control.From pure springs flowing effortlessly to the tongue that required constant correction, this is Victorian feminine conversation in all its terrified, tongue-tied glory.Features readings from "The Young Lady's Book" (1888) by Matilda Ann Mackarness

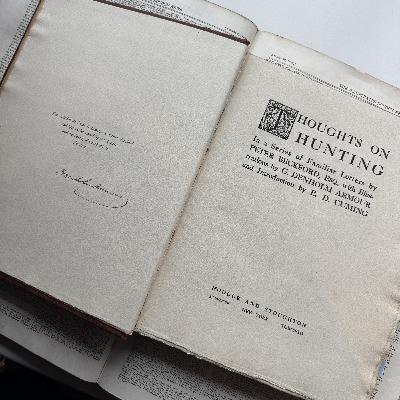

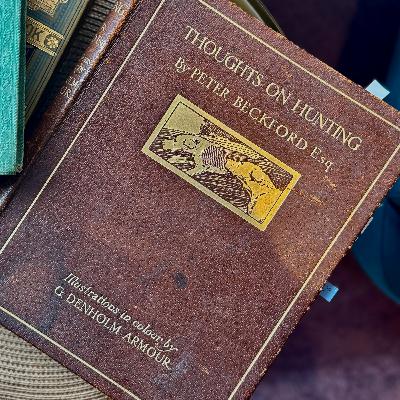

Two hounds clung to each other all night on a hedge surrounded by freezing floodwater. When the water receded the next morning, they were found "closely clasping each other—without doubt, it was the friendly warmth which they afforded each other that kept both alive." This is Peter Beckford in crisis, showing his true character when his beloved pack faced disaster.Part 2 of our journey through the 1787 hunting masterpiece moves from literary art to practical animal care—revealing both Beckford's surprisingly advanced veterinary knowledge and the dangerous medical practices of his era. Discover his mange treatments: sulfur, whale oil (train oil), and turpentine created an effective, safe remedy still used today in some forms. But red mange required something stronger—quicksilver (liquid mercury) mixed with turpentine and hog's lard, rubbed directly onto the dog's skin for three consecutive days. It killed the parasites. It also frequently killed the dogs and likely poisoned the staff applying it without gloves (rubber gloves weren't invented until 1894).Learn about the distemper epidemic devastating kennels across Britain with 50-90% mortality rates, Beckford's experimental treatments (Peruvian bark with port wine, opium-based Norris drops), his proto-scientific approach ("I shall not recommend such as have not been tried with success"), and his surprisingly modern insight that fresh air, clean bedding, isolation of sick animals, and feeding multiple dogs together to encourage eating were the best defenses.But the emotional heart of this episode is the river crossing disaster: floodwater so deep horses nearly swam, current so strong it swept hounds downstream, freezing temperatures leaving survivors unable to walk. Beckford watched helplessly as his pack exhausted themselves trying to reach him, their "well-known tongues as such I had never heard before or without pleasure." The scene of two hounds spending the night clinging to each other on a hedge is genuinely moving.Yet here's the contradiction: a man who knew each hound by name, kept detailed performance records, and showed extraordinary compassion for animal suffering lived comfortably on profits from Jamaican sugar plantations worked by enslaved people he never met. Between 1780-1786, five hurricanes destroyed his income, his wife left him, his son gambled away fortunes, and by the end, he was selling estates and mortgaging what remained.Features readings from "Thoughts on Hunting" by Peter Beckford (1787), including kennel design, veterinary treatments, the river disaster account, and his philosophical comparison of hunting to other sports.

This is the book that inspired the entire podcast. In a Westport bookshop, six American tourists watched Avril read aloud from a 1787 hunting manual—amused by passages about dogs "emptying themselves" for kennel cleanliness. One woman turned back in the doorway and said: "You should do a podcast on old books." So here we are.Peter Beckford's "Thoughts on Hunting" (1787) has remained in continuous print for over 240 years, not because it's a simple hunting manual, but because it's a literary masterpiece. This educated gentleman—fluent in Greek, Latin, Italian, and French—elevated practical fox hunting instruction into elegant prose peppered with classical quotations. He would "bag a fox in Greek, find a hare in Latin, inspect his kennels in Italian, and direct the economy of stables in exquisite French."Discover the origin story: Beckford published anonymously until a disgruntled clergyman critic prompted him to release an expanded edition with his name attached, directly answering criticisms in footnotes throughout. Learn the rigid class hierarchy of Georgian hunting—Huntsman (leader/strategist), Whipper-in (tactical assistant maintaining pack discipline), and Feeder (essential establishment member). Read the most hilariously terrible character reference ever written: John G starts as "rides pretty well" and deteriorates into "voiceless, dishonest thief, drunk, notorious liar, half a fool, killer of horses."But the crown jewel is Letter 13—Beckford's fictional hunt that alternates between his prose and William Somerville's poetry, creating a breathless chase from "Hark! they're on the drag" through countryside, over hedges, across plains, until "Ha! they have him. Whoo!" It's Georgian literature at its finest—practical instruction transformed into art.Features readings from "Thoughts on Hunting" by Peter Beckford (1787), including the complete Letter 13 hunt sequence with William Somerville's "The Chase" (1735) poetry integrated throughout.

How can you tell if a woman will make a good wife? According to William Cobbett's 1829 advice manual, take her out for a mutton chop and watch her jaw movements. Firm, decisive biting indicates good character. Tentative squeezing indicates disaster.This episode explores one of the most entertainingly bizarre marriage advice books ever written by a man uniquely qualified to give it—not because he was a relationship expert, but because he'd been married to the same woman for 37 years through imprisonment, multiple exiles, financial ruin, and the time he dug up Thomas Paine's bones for a heroic burial that never happened. William Cobbett was a radical reformer who'd been sued for libel multiple times, imprisoned for two years, and fled countries on three separate occasions. But through it all, Anne Reed was there.Discover Cobbett's physical tests for detecting wife material: walking speed reveals capacity for love (quick step with heavy tread = good, sauntering = cold-hearted mother), jaw movements predict industriousness (watch her eat cheese for the truth), voice quality indicates laziness ("mawmouth women" who let sounds fall out are disgusting), and general "sobriety of conduct" (steady, serious, no capering). These weren't just Georgian superstition—they reflected widespread belief in physiognomy, the idea that moral character could be read from physical features and behaviors.But here's where it gets fascinating: Cobbett demands absolute wifely obedience (a henpecked husband should drown himself, apparently), yet his own behavior tells a completely different story. When Anne was 14, he sent her his entire life savings (150 guineas, roughly £22,000 today) and told her to spend it on comfort. Four years later, she handed it back untouched—she'd worked as a servant for £5/year and saved every penny. When they married, he spent entire nights walking barefoot through Philadelphia streets throwing stones at dogs so the barking wouldn't disturb her sleep. He helped with the baby, lit fires, boiled tea, and rushed home through thunderstorms because he knew she was frightened.The contradiction is remarkable: a man who insists on male authority while demonstrating extraordinary devotion. Who demands wives obey but spends his life serving his wife's comfort and happiness.Features readings from "Advice to Young Men and (Incidentally) to Young Women" by William Cobbett (1829), complete with his accounts of courtship, marriage, exile, and the devoted partnership that survived everything Georgian England could throw at them.

In 1645, Matthew Hopkins declared himself the "Witch Finder General" and began a reign of terror that executed more people in two years than the previous century combined. His secret? Systematic methods for detecting familiar spirits—demonic creatures with names like Pyewacket, Vinegar Tom, and Grizel Greedigut.This second part of our witch trials series moves from legal corruption to examine the supernatural evidence itself: the signs, spirits, and suffering that convinced communities they were surrounded by Satan's servants. Drawing from the 1847 London Journal's extensive investigation, discover how professional witch hunters transformed ordinary life into proof of diabolic conspiracy.Explore the world of familiar spirits—physical demons that required feeding, shelter, and care while leaving evidence on human bodies through "witch marks" (supernatural nipples for nursing demons). Learn how Elizabeth Clarke confessed under torture to five distinct familiars: Holt the white cat (caused illness), Jamara the red spaniel (killed livestock), Vinegar Tom the greyhound (carried messages), Sack and Sugar the black rabbit (spied on enemies), and Newes the polecat (contaminated food supplies).Discover the sophisticated torture techniques: the boots (iron devices that crushed leg bones), thumbscrews, systematic sleep deprivation combined with forced walking, pricking for insensitive marks using retractable needles, swimming tests (float = guilty, sink = innocent but drowned), and prayer tests designed to guarantee failure among the vulnerable. These weren't random cruelties but carefully designed procedures developed by educated professionals who understood exactly how to break human resistance.Plus: flying ointments containing belladonna and mandrake, weather magic accusations against King James VI's voyage, shape-shifting evidence (injured cats = wounded women miles away), healing knowledge that became diabolic conspiracy, and the staggering scale: 157 people burned in Würzburg in just two years (1627-1629), including children as young as nine.Features readings from London Journal (1847), Matthew Hopkins' documented cases, Scottish torture records, and European Inquisition accounts.Part 2 of 2 - Companion to Part 1 on legal corruption and spectral evidence.

Enter the darkest chapter of legal history, where witch trials transformed courtrooms into instruments of systematic terror. Part 1 of this two-part series explores how the pursuit of witches corrupted entire legal systems, abandoning every principle of justice to hunt invisible enemies.From Salem's witch trials using spectral evidence that made defense impossible, to the Malleus Maleficarum's witch-hunting manual that created papal-sanctioned "commissions of fire and sword," witness how learned professionals deliberately corrupted judicial institutions to prosecute witchcraft. Discover King James VI's personal supervision of witch torture sessions, Richard III's theatrical use of witchcraft accusations for political murder, and the gendered violence that made women 80-90% of all witch trial victims.Through accounts from the 1847 London Journal, explore how witch-hunting created "objective" evidence from shape-shifting accusations, how Scottish witch trials became royal entertainment, and how these prosecutorial innovations persisted into the Victorian era when fishermen still sought to draw witches' blood for protection.This episode examines the systematic techniques developed specifically for witch prosecution—spectral evidence, enhanced torture, presumption of guilt—and how these innovations abandoned traditional legal protections as "obstacles" to hunting supernatural criminals. The witch-hunter's toolkit created frameworks for systematic persecution that could be revived whenever new enemies required elimination through judicial channels.Part 1 of a 2-part series on how witch-hunting transformed European and American legal systems.Content Advisory: Contains historical accounts of torture, execution, and systematic violence, particularly against women.

How did civilization's greatest achievement—the rule of law—become humanity's most efficient killing machine?In Colonial Salem, 1692, young girls screamed that invisible spirits were attacking them. The accused sat physically present in the courtroom, yet prosecutors claimed her spirit had separated from her body to commit diabolic violence miles away. This was spectral evidence: testimony about crimes committed by invisible forces while the accused was provably elsewhere. Defense became impossible. Alibis became meaningless. And the legal system transformed into an engine of systematic murder.This two-part series explores how European and American courts deliberately abandoned every principle of justice—presumption of innocence, right to confront accusers, credible witnesses—to prosecute supernatural crimes. Drawing from the 1847 London Journal's extensive investigation into witchcraft prosecution, this episode reveals the sophisticated legal machinery designed to eliminate society's most vulnerable members, primarily women (80-90% of victims), through procedures that appeared rational and legitimate.Discover how the 1487 manual "Malleus Maleficarum" created new categories of evidence and redefined burden of proof; how Papal "commissions of fire and sword" created mobile death squads answering only to Rome; how Richard III used witchcraft accusations as political weapons (strawberries to execution in under two hours); how King James VI of Scotland personally supervised torture sessions, taking "conscious delight" in extracting confessions; and how shape-shifting accusations created seemingly objective evidence of supernatural transformation that survived into 1845 Scotland.This isn't primitive superstition—it's the systematic corruption of judicial institutions by learned men who understood exactly what they were creating: a legal framework that could eliminate any targeted population while maintaining the facade of legitimate justice.Features readings from London Journal (1847), "Malleus Maleficarum" legal procedures, King James VI's "Daemonologie" (1597), and Scottish court records through 1845.

A fox screaming at 3 AM outside your window sounds terrifying—but in 18th century Ireland, there was something far more chilling: the Banshee's whale announcing death in your family.When a midnight fox raid on host Avril's henhouse left her wide awake at 3 AM, she picked up an 1847 issue of the London Journal and discovered chapters on Irish supernatural folklore. What followed was a deep dive into the eerie world of the Banshee—the "fairy woman" whose otherworldly cries heralded death in certain Irish families. This episode explores the most spine-tingling Banshee accounts from the 1700s-1800s: Charles McCarthy's exact prophecy of his own death three years in advance, Mrs. Barry's terrifying road encounter with a tall spectral woman in white who physically redirected their horse cart, and Kavanaugh the herdsman's journey from Mallow accompanied by wailing and hand-clapping every step of the way.Discover the Irish keening tradition that may have birthed the Banshee legend, why only certain families (particularly those with O', Mac, or Mc surnames) were "honored" with a Banshee, and why the dying person never heard the warning—only their loved ones did. Plus: European variations including Scotland's phantom horsemen, Wales' Cyhyraeth (a leather-winged hag), Germany's gigantic grave-wrapped woman of the Luenberger Heath, and the White Lady of Brandenburg.These aren't just ghost stories—they're windows into how Irish and European communities processed grief and mortality before modern communication. The Banshee served as a "supernatural telegraph system," connecting families across time and space.Features readings from the London Journal (October 16, 1847), "Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland" by Thomas Crofton Croker (1838), Chambers's Edinburgh Journal (1878), and Lady Fanshaw's manuscript accounts.

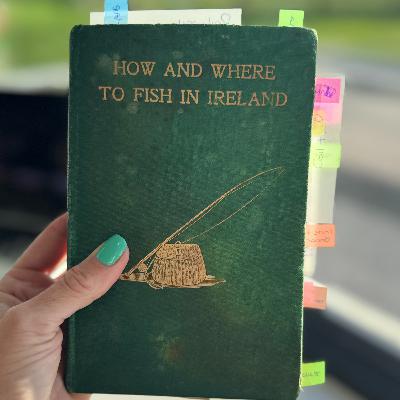

What do you get when a dishonorably discharged soldier, debtor's prison survivor, and perpetual scandal writes a fishing guide? A Victorian bestseller that went through 17 editions.In 1886, Captain John Joseph Dunn (writing as "Hi Regan") published "How and Where to Fish in Ireland"—ostensibly a practical fishing manual, but actually a hilarious window into Victorian Ireland complete with paraffin-based midge repellent, whiskey-for-your-feet advice, and a strap-on device called a "coil horn" that isn't what you think it is. Host Avril takes you through this moldy treasure (literally—the book arrived covered in actual mold) to uncover the story of a charming rogue who lived on "air and other people's money" while somehow befriending dukes, dodging debt collectors, and writing one of Ireland's most enduring fishing guides.Discover Victorian fishing techniques that involved setting yourself on fire with paraffin mixtures, railway networks instead of roads (pre-1896 cars), counties with different names (Kings and Queens County before 1922), and the delicate art of bribing boatmen with whiskey and "dowsers" (tips). Plus: trout cooked in grease paper over turf embers, landlord permissions for river access during the Famine era, and why County Mayo is "perhaps externally and internally, the wettest county in Ireland."But the real twist? Captain Dunn's daughter Mary Isabelle became "George Egerton," one of the most important feminist authors of the late 1800s. While dad wrote about catching trout, she wrote about women catching their independence.Features readings from "How and Where to Fish in Ireland" by Hi Regan (Captain John Joseph Dunn), 10th edition (1900), originally published 1886.

Ever wondered what happens when someone with dyslexia, an aggressive browsing habit in vintage bookshops, and absolutely no qualifications in English history decides to start a podcast? You're about to find out.Welcome to Vices and Volumes, where host Avril Clinton-Forde reads from her personal collection of books spanning the 1700s through the 1920s—and dives headfirst into the wonderful rabbit holes they create. This introduction episode explains how an impromptu performance for six American tourists in a West Coast Ireland bookshop led to a podcast dedicated to exploring the delightfully complex way the upper classes made simple instructions sound like diplomatic negotiations.What you'll discover in future episodes: Victorian etiquette that makes modern dating apps look simple, Irish folklore and banshees, servant management techniques more insightful than modern leadership books, hunting protocols with existential overtones, and the elaborate way Georgians and Victorians made the English language perform Olympic-level gymnastics just to say something simple.This episode features readings from "Thoughts on Hunting" and "Bear Recital" (18th-19th century), including the immortal wisdom: "A slip of the tongue is no fault of the mind," and why masters who don't understand their servants' duties will find those servants inevitably idle.Whether you're here for history, curiosity, relaxation, or honestly just hoping something will help you fall asleep, Avril has you covered. Episodes include fully researched deep dives and "bare recitals" where the original Victorian and Georgian texts speak for themselves.Perfect for: History lovers, insomniacs, literary curiosity seekers, and anyone who gets genuinely excited about 200-year-old instructions for proper hat storage.