Discover Catholic Saints & Feasts

Catholic Saints & Feasts

Catholic Saints & Feasts

Author: Fr. Michael Black

Subscribed: 49Played: 1,155Subscribe

Share

© Copyright Fr. Michael Black

Description

"Catholic Saints & Feasts" offers a dramatic reflection on each saint and feast day of the General Calendar of the Catholic Church. The reflections are taken from the four volume book series: "Saints & Feasts of the Catholic Calendar," written by Fr. Michael Black.

These reflections profile the theological bone breakers, the verbal flame throwers, the ocean crossers, the heart-melters, and the sweet-chanting virgin-martyrs who populate the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church.

These reflections profile the theological bone breakers, the verbal flame throwers, the ocean crossers, the heart-melters, and the sweet-chanting virgin-martyrs who populate the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church.

275 Episodes

Reverse

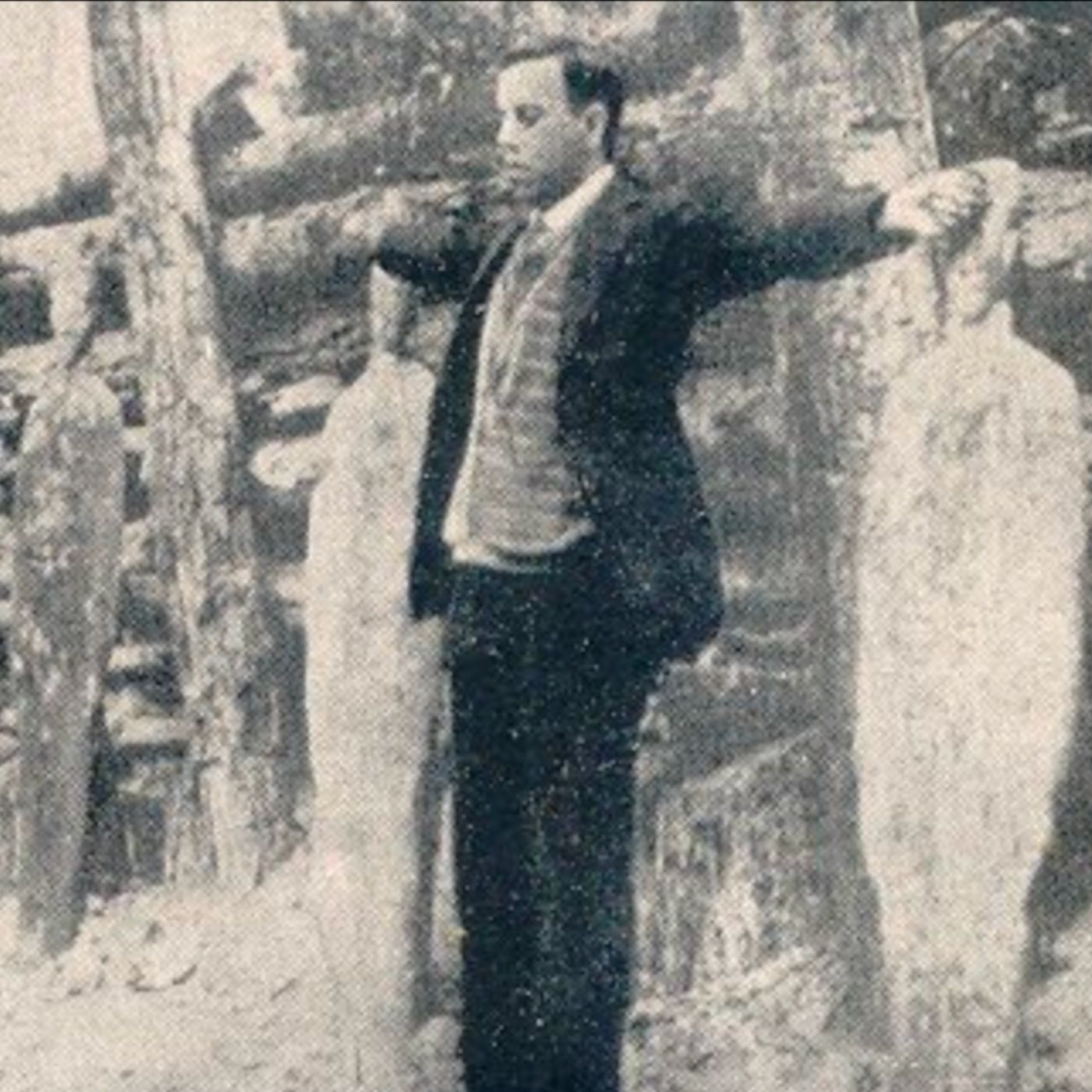

November 23: Blessed Miguel Agustín Pro, Priest and Martyr (U.S.A.)1891–1927Optional Memorial; Liturgical Color: RedThe proto-martyr of the age of the imageThe emaciated holocaust survivor behind the barbed wire, gazing out, bewildered, as the Allied soldiers walk up to the camp. Click. The slack body of a black man hanging from a stout limb, a thick crowd of whites gathered around. Click. A soldier shooting a young Viet Cong prisoner in the head on the frenetic streets of Saigon in 1968. Click. The President zooming through Dallas in a convertible when… Click. In the age of the image, a camera is always clicking or a device recording the action. Modern reality is experienced through images, lenses, and screens more than words. Like a red-hot iron searing a brand into a hide, a powerful image sizzles as it presses itself into our brains.The photos of the execution of today’s martyr blister the mind. There are no photos of Polycarp as the flames licked his skin, of Felicity and Perpetua stumbling as the heifer ran them down, or of Kolbe quietly offering his life for a stranger in grim Auschwitz. The indelible photos of Father Pro being shot will have to suffice for all the undepicted others. The high drama of Pro’s last moments must substitute for every Christian stuffed in the trunk, worked to death in the Siberian gulag, or burned at the stake. No last words or gestures were recorded as the terror closed in on them. For so many who were “disappeared,” there were no witnesses, no documents, no legacy, no clicks.Miguel Pro was born into a middle-class family in North Central Mexico. His family was large, pious, and close in the best Latino tradition. Miguel received his First Holy Communion from Fr. Mateo Correa, who would be executed just a few months before Father Pro for not revealing the confessions of his fellow prisoners. A much loved sister of Miguel’s became a nun, a Christian witness which inspired Miguel to enter a Jesuit seminary. Miguel’s seminary studies in Mexico were interrupted by the spasms of anti-Catholic violence which convulsed Mexico throughout the early twentieth century. He had to flee the country and studied in California, Nicaragua, Spain, and, finally, Belgium, where he was ordained a priest in 1925. The other men ordained with him gave their customary first priestly blessing to their parents after the ordination Mass. Father Miguel’s entire family was in Mexico, so he went back to his room, laid out all his family photos on a table, and blessed the pictures. Fr. Pro’s first apostolic labors were in Belgium among working class miners. His health was a problem from his youth. He suffered painful bleeding ulcers, which required several marginally successful surgeries to repair. This constant physical discomfort likely hardened his will, deepened his life of prayer, and steeled his body for the heroism to come. Years of faithful attendance at the school of human suffering had braced him. Fr. Pro was a man in full.In 1926 Father Pro returned to Mexico and began a clandestine priestly ministry in an atmosphere of high tension. Mexico’s lords of evil had a phobia of Catholicism and outlawed its every expression, from the wearing of priestly garb to the public celebration of the Sacraments. Pro was hunted like a bandit. In November 1927, an unsuccessful assassination attempt on the president-elect provided the pretext for punishing Pro, who was guiltless. He was discovered in his hideout. There was no trial, no evidence, no counsel, no defense, no judge, no jury, no verdict, and no sentence. There was just a squalid firing range down the street. It was November 23. A photographer was sent to capture, for propaganda purposes, Pro begging for mercy. Not a chance! Father Pro briefly knelt in prayer, declined a blindfold, kissed his crucifix, and then stood and spoke in a strong voice: “May God have mercy on you! May God bless you! Lord, you know I am innocent! With all my heart I forgive my enemies! Viva Cristo Rey!” He then elevated his arms like the crucified Savior, a rosary in one hand and a small crucifix in the other when...click, click, click, click. It was 10:38 a.m. Pro is frozen in time. He is forever young. He is not before or after. He is his last seconds. He is those photos. To die is to do something. Blessed Miguel Pro did it as well as anyone ever did. He was beatified in 1988 and his memorial placed one week before the feast of Christ the King.Blessed Miguel Pro, your gripping last moments sear the mind and pierce the heart. Grant us just an ounce of your ocean of daring, fortitude, and perseverance in living and sharing the faith. Help us to be more like you!

November 23: Saint Clement I, Pope and MartyrFirst CenturyOptional Memorial; Liturgical Color: RedPatron Saint of sailors and marble workersPrimacy more than infallibility, service more than authorityOur loving maternal Church expresses herself through a paternal structure which makes decisions, resolves conflicts, intercedes in disputes, and governs the people who voluntarily gather in her strong embrace. The Marian Church of discipleship is without sin, like the Virgin herself, but the Petrine Church of authority is founded on a heroic, but flawed, man. Because it is rooted in the life of Saint Peter, Church governance is, by its nature, as imperfect as it is necessary. So while the pure Church of Mary awaits discovery in heaven, her pristine beauty is disfigured in this world by her commingling with the oh-so-human Church of Peter. The highest expression of the Church’s authority is the sole office built over the words of Christ Himself—the papacy. Today’s Memorial commemorates the third successor of Saint Peter, who served as the Bishop of Rome in the last years of the first century. Pope Clement I and his two predecessors are named in Eucharistic Prayer I just after the list of the Twelve Apostles: “Linus, Cletus, Clement…” Though few details of Clement’s life are known, what is known is surpassingly important. Clement is the very first Apostolic Father and may have been ordained by Saint Peter himself. In about the year 96 A.D., Clement wrote from Rome to the Church in Corinth to resolve some undefined disputes over authority tearing at that congregation. Clement’s letter is one of the most ancient Christian documents after the New Testament itself. It was so significant that in the second century it was read at Mass in Corinth and, in other regions, was considered part of the New Testament Canon! The tone of Clement’s long letter is fraternal rather than domineering, more like an encyclical than a decree. Pope Clement encourages the faithful to be obedient to their priests and bishops, to be inspired by the example of the martyrs, and to lead lives of high moral virtue. The Church of Corinth could have looked to Saint John the Evangelist for guidance. In the late first century, he was an old man living in Ephesus, a city much closer to Corinth than Rome. But it was the long-dead Peter whose shadow towered over Corinth, not the living John.Clement’s letter reveals an even-tempered soul, a shepherd eager to preserve the tenuous unity of his flock. The letter is invaluable as a proof of the centrality of the Bishop of Rome from the first chapter of the Christian story. The service of apostolic authority, of an interior organizing principle, is intrinsic to the Gospel itself, not a later addition. The primitive papal primacy exercised by Clement is not the imposition of a foreign power structure on an otherwise dreamy and innocent Church. The proto-Christians of Corinth needed clear, fatherly, instruction as they struggled to implement the Christian revolution in their homes, villages, shops, and town squares. Saint Paul had to write to them twice using strong language. It was evidently not enough, hence Clement’s letter a few decades later.As the first generations of Christians realized that Christ was not going to return before they died, their understanding of the Church matured. Personal prophecies, individual teachings, and private spiritual gifts had to be incorporated into the broader life of the quickly expanding church. These personal gifts thus became subject to Church approval and to conformity with Scripture and previous teachings. In Clement’s time, the Church, rather than individuals, slowly became the repository of the accumulated wisdom of Christianity. And this early Church was not merely a society of learned men, an association of the perfect, or a cultural enrichment club. It was, and still is, a real Church, and so did what a real church does. The Corinthians, with Clement’s help, knew this essential fact—that to be a Christian and to be a member of the Church was one and the same thing.Saint Clement, you spoke with fatherly authority to faithful men and women struggling to preserve Christian unity. May your balanced example inspire all in Holy Orders to gather, not scatter, to encourage, not scold, as they teach, preach, and govern in the name of Christ.

November 22: Saint Cecilia, Virgin and Martyrc. Third CenturyMemorial; Liturgical Color: RedPatron Saint of Music and MusiciansA girl martyr’s mysterious death seizes the imaginationThe First Eucharistic Prayer, also known as the Roman Canon, is principally a liturgical document. But like so many things liturgical, it also has immense historical value. Only a tiny fraction of the ancient world’s documents have survived. Archives flood, libraries burn to ash, monasteries collapse, castles are sacked, and coastlines erode—the cities perched above them crumbling into the waves, everything lost, as the sea pushes inland. When documents disappear, historians must work from scraps of pottery and marble, or from the detritus of watery shipwrecks, to gather just tiny pieces of the fuller mosaic of what once was. The Catholic Church is a phenomenal exception to culture’s progressive Alzheimer’s. In its law, catechisms, calendar, feasts, buildings, hierarchy, and most especially in its liturgy, the Church’s past is never really past. Catholicism’s collective memory is stored, not in rack upon rack of digital servers in hermetically sealed rooms, but in the minds of its hundreds of millions of adherents. The faithful are the cloud. Priests and religious in particular circulate the living faith, ensuring that it is perpetually churning, flowing, and spreading like a rushing river.The names of the martyrs listed in the Roman Canon include today’s saint, Cecilia. From one perspective, that is all we need to know. She lived. She was martyred. She was remembered. Cecilia’s name was included in the only Eucharistic Prayer then said at Sunday Mass, presumably because she stood out from the many other martyrs for a particular reason. That reason has been lost. Perhaps a stirring homily, committed to writing, preserved moving details of Cecilia’s life and tragic death. But maybe that homily was converted to cinders and slowly floated away when the enormous library of the Monastery of Cluny burned during the French religious conflicts of the 1500s. Perhaps there was a biographically detailed marble epitaph over Cecilia’s grave in the catacombs. Yet maybe that epitaph was wrenched from the wall by a barbarian plunderer who later used it as a sturdy doorstep for his house in Aachen. Cecilia’s details are lost, for reasons unknown. But the Roman Canon is not lost, and it gathers together some notable virgin martyrs of the first few centuries: “...Agatha, Lucy, Agnes, Cecilia, Anastasia…” Like flies in amber, their names are preserved, to be heard in hundreds of languages by millions of people every week until the end of time.Cecilia was likely martyred by cuts to her neck after attempts to steam her to death were unsuccessful. She was then buried in a loculus near the papal crypt in the Catacombs of Saint Callixtus. After being the object of devotion in the catacombs for centuries, Cecilia’s remains were transferred by the Pope in the early 800s to her own Basilica in the Trastevere neighborhood of Rome. During some restoration work on the Basilica in 1599, Cecilia’s body was uncovered and found to be incorrupt. Before contact with the atmosphere caused her fragile, paper-mache like skin to disintegrate, an artist carefully noted what he saw. His sculpture of Saint Cecilia is evocative and justly famous. The marble itself seems to rest in peace. It is not a forward, glorious pose in the Counter-Reformation tradition dominant when the statue was executed. The marble is white, reflecting Cecilia’s purity. The saint’s face and hair are mysteriously covered by a sheet, inviting the mind to wonder. Cecilia’s fingers seem to form a cryptic Christian symbol of the Trinity—Three in One. And her neck is sliced by the stroke of an axe. The sculptor’s personal testimony is embedded in the floor near his work: “Behold the body of the Most Holy Virgin, Cecilia, whom I myself saw lying uncorrupt in her tomb. I have in this marble expressed for thee the same saint in the very same posture and body.” We don’t know the full story of our saint, but we are certain of her end—a generous act of self gift to Christ.Saint Cecilia, you died an early death, preserving your virginity and choosing Christ over all others. Be an example to all youth of the true goal of their lives. Help them to seek God first and the good and holy pleasures of life only after Him.

November 21: The Presentation of the Blessed Virgin MaryMemorial; Liturgical Color: WhiteMary was likely consecrated to God as a childStillbirths, infant mortality, and mothers’ dying during labor have been among the most predictable human tragedies since time immemorial. Medical progress has only in recent generations dramatically reduced such deaths, albeit unevenly throughout the world. In light of the real dangers of pregnancy and childbirth, the successful birth of a healthy baby has naturally given rise to ceremonies in many cultures thanking God for the precarious gift of new life. Jewish law required the ritual dedication of first-born sons to God in the Temple. It is probable that a similar custom, if not a law, called for Jewish girls to also be so dedicated. It is the likely presentation of the child Mary in such a ceremony that we celebrate today.The Church does not claim that today’s feast is rooted in Sacred Scripture. There is no direct biblical support for Mary’s Presentation except in the apocryphal “Gospel” of Saint James, a problematic text replete with follies. The lack of textual support is, nevertheless, no reason to doubt the ancient tradition, especially preserved in Eastern Orthodoxy, that Joachim and Anne consecrated Mary, their daughter, to God at the age of three in the Jerusalem Temple. The prophet Samuel was similarly presented by his mother, Hannah. Both Hannah and her namesake, Anne, were long barren and were thus all the more grateful to see the fruit of their unexpected pregnancies.It is a good and holy thing for Christian parents to proactively dedicate their children to God, or even to invite them to consider a life consecrated to God as priests or religious. While some may consider it an unwise imposition for parents to so explicitly encourage their children to take steps down that holy path, all parents, in fact, are energetic in promoting some level of conformity with their own religious or quasi-religious beliefs. These “beliefs” may be related to the environment, politics, leisure, art, sports, or a thousand other causes or hobbies. Parents always indoctrinate their children. It is intrinsic to their role. The only question is what the content of that indoctrination will be. Ideally, Christian parents hand on to their children their most deeply held beliefs—including their faith in Jesus Christ.The essence of any sacrifice is to burn, kill, or destroy something of value in order to close the yawning gap between God and man. A sacrifice can be in thanksgiving, to repent of a sin, or in petition for a favor. Primitive priests in cultures across the globe since time immemorial have stood at their rough stone altars on behalf of their people to offer God fatted calves, heifers, sheep, the finest grain, red wine, and even their fellow man. Abraham was willing to offer his very own son to God. Blood sacrifice gradually receded in Judaism, however, to bloodless sacrifice, and eventually to non-sacrificial pathways to God. The age of priests in the Jerusalem Temple sacrificing animals gradually mutated, from the late first century onward, into rabbis in synagogues teaching from books.To present a child to God, either in a formal ritual or in a private dedication, is to lay that child on a symbolic altar and to say to God: “You create. We procreate. My child is Your child. Do with this child as You will.” Such humble and antecedent submission to the will of God is not an abdication of the duty to form a child in human and religious virtue. It is just to be realistic. Children are gifts, not metaphorically but actually. A child is not a piece of property or an object a parent has a right to possess. No one understands this like the infertile couple. When parents consecrate a child to God, whether at baptism or otherwise, even informally, they are manifesting a willingness to return a gift to its remote source, to please the Maker by giving Him what He already possesses, life itself and all who share in it.Saints Anne and Joachim, in gratitude for the gift of life, you presented Mary in the Temple. Help all young parents to see in you a model of dependence on God’s providence and may similar consecrations in today’s world prepare saints for the Church of tomorrow.

November 20: Saint Bernward of Hildesheim, Bishopc.960–1022 Optional Memorial; Not on Universal Calendar; Liturgical Color: White Patron saint of goldsmiths & architects A well-educated and pious bishop sponsors the practical arts Some doors in the city of Rome draw people in like huge vertical magnets, pulling groups of pilgrims slowly towards them across broad atriums. The dots of laser pointers dance over the doors of the Basilica of St. John Lateran as guides point and explain how these towering doors once swung open onto the Roman Curia, where senators in white togas stood debating matters of empire. The colossal, sober, bronze doors of the 2nd century Pantheon still hang from its jambs. And the large, intricate, wood paneled doors of Santa Sabina date from the 430s! The eyes of today’s saint, Bernward of Hildesheim, gazed up in wonder at these very same sets of doors when he visited Rome in the year 1001. And while he gazed, he also resolved to carry back just a bit of this Roman elegance, this Roman nobility, this Roman weight, to the cold land, to the far land, he had come from. St. Bernward of Hildesheim lived at the half-way point between us and Jesus Christ. His life spanned mankind’s crossing from the first to the second millennium. Bernward had an impeccable pedigree, with the branches of his noble family tree extending throughout lower Saxony, in today’s northern Germany. His family lineage, fine education, and personal piety opened doors of power and influence to him throughout his life. He was chosen as the tutor to the most important man of his time and place, Otto III, who became the Holy Roman Emperor. And he was appointed bishop of Hildesheim at a young age in 993 and remained in that position, and in that town, until he breathed his last thirty years later. Bernward lived long before the founding of the great universities of Europe, in an age when monasteries and cathedrals were Europe’s preeminent centers of learning. A cathedral school, in particular, was the equivalent of an elite prep school today. It was as important to a diocese as the cathedral itself. Bernward attended the cathedral school of Hildesheim as a youth long before becoming bishop of the same diocese. The academic theology done in Europe’s universities starting in the 1200s created a more disciplined and professional guild of theologians but moved theology to a neutral location. In Bernward’s more feudal age, men learned theology in the beating heart of the church, in the red-hot centers of prayer and apostolic activity where the faithful habitually gathered – in cathedrals and monasteries. Bishops, thinkers, and authors baptized babies, said funeral masses, anointed the sick, sang vespers, and led processions while also studying and writing. Their audience was the faithful. Their forum was the pulpit. University-based theology was severed from the great centers of spirituality so familiar to the first millennium. It was more scientific, yes, but also more dry. St. Bernward was a man of the first millennium. His public was not other academics but his happy people. His theology was both intellectual and practical, with church ideas and church life braided tightly together, as they should be. Bernward mastered the seven liberal arts common to his age and showed a keen interest in practical craftmanship. He was an energetic bishop who commissioned the building of castles, an abbey, and numerous decorative items for his churches. Inspired by his extended roman visit, he ordered a huge set of bronze doors for his cathedral, known as the Bernward doors. These commanding pieces of functional art, with their simple but expressive figures in deep relief, can still be admired today. They were not made of perishable material. They were made to last and have lasted for half the life of the church. St. Bernward’s kind disappeared with his epoch. The monastic reforms of Cluny and the later groundbreaking ways of the Franciscan and Dominican Orders spread like wildfire in the 1200s and brought a definitive end to first millennium Catholicism. We remember St. Bernward today because he was a model bishop committed to one diocese and one people in matters practical and spiritual. St. Bernward, your education, piety, mortification, and practical concern for your faithful have kept the flame of your memory burning in your see city. We seek your divine intercession on behalf of all bishops, that they may emulate your fund of virtues. Amen.

November 18: Saint Rose Philippine Duchesne, Virgin1769–1852Optional Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhitePatron Saint of perseverance amid adversityBorn into a refined French family, her life ended in hardship on the American prairieToday’s saint was born into a large, refined, educated Catholic family situated in an enormous home in the venerable city of Grenoble, France. Rose’s parents and extended family were connected to other elites in the highest circles of the political and social life of that era. Despite this favored parentage, Rose would leave the world and all the advantages she inherited to become a hardscrabble missionary nun serving rough settlers and Indians in the no man’s land of the American plains. Saint Rose was named after the first canonized saint of the New World, Saint Rose of Lima. As a child, her imagination had been fired by hearing about missionaries on the American frontier. She dreamed of being one of them, yet her path to becoming a pioneer missionary would be circuitous.When Rose felt the call to a contemplative religious life as a teen, she joined, against her father’s wishes, the Order that so many French women of status joined—the Congregation of the Visitation, founded by Saint Jane Frances de Chantal in the early seventeenth century. The massive social upheavals of the French Revolution shuttered her Visitandine convent, though, and she spent years living her Order’s rule privately outside of a convent as her country disintegrated into chaos. After the revolution, when religious life was no longer illegal, Rose tried to re-establish her defunct convent by personally purchasing its buildings. The plan didn’t work, and Rose and the few remaining sisters united themselves to a new French Order, which would later be known as the Religious Sisters of the Sacred Heart.Saint Rose was destined to be a holy and dedicated nun in her Order’s schools. But in 1817, a bishop serving in the United States came to France on a recruitment tour, as so many bishops did in the first half of the nineteenth century. The bishop visited Rose’s convent in Paris, and Rose’s childhood dreams were rekindled. After receiving permission from her superiors, in 1818 Rose boarded a ship with four other sisters for the two-month sea voyage to New Orleans, U.S.A. The second act of her life was starting at age forty-nine. From this point forward, her life was replete with the physical hardships, financial struggles, and everyday drama typical of the French and Spanish missionaries who brought the faith to the ill-educated pioneers and Indians on the edge of the American frontier.Rose and her troupe of sisters had to take a steamboat up the Mississippi River to Missouri after the bishop’s promises of a convent in New Orleans came to nothing. In remote Western Missouri, Rose began a convent in a log cabin and then started a school and a small novitiate. The people were poor, the settlers generally unschooled, the weather cold, the food inadequate, and life hard. Rose struggled to learn English. Yet after ten years, the Sacred Heart Sisters were operating six convents in Missouri and Louisiana. In 1841, the Sisters began to serve Potawatomi Indians who had been harshly displaced from Michigan and Indiana into Eastern Kansas. At seventy-one years old, Rose joined this missionary band to Kansas not for her practical usefulness but for her example of prayer. Saint Rose prayed so incessantly that she was on her knees before the tabernacle when the Indians went to sleep and kneeling there when they woke up, still praying. Wondering at this, some children put pebbles on the train of her habit one night. The next morning the pebbles were still there. She hadn’t budged an inch all night long! The Potawatomi called her “She Who Prays Always.” Howling cold and the rigors of frontier life forced Rose to return to a more humane convent existence for the last quiet years of her life. She was beatified in 1940 and canonized in 1988.Saint Rose, you persevered heroically in your vocation despite serious challenges. Inspire all religious to continue in their unique vocations despite setbacks, and to unite, as you did, a quiet contemplative soul with a missionary’s courage and drive.

November 18: The Dedication of the Basilicas of Saints Peter and Paul, ApostlesOptional Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhiteThe Apostles Peter and Paul are the Patron Saints of the City of RomeThe barque of Peter is tethered to two stout anchorsA cathedral is theology in stone, the medievals said, a truism which extends to all churches, not just cathedrals, and to their sacred web of translucent glass, glowing marble, gold-encrusted wood, bronze canopies, and every other noble surface on which the eye falls. A Church mutely confesses its belief through form and materials. Today’s feast commemorates the dedication of two of the most sumptuous churches in the entire world: the Basilica of St. Peter, the oversized jewel in the small crown of Vatican City, and the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls, a few miles distant, beyond Rome’s ancient walls. The foundations of these two Basilicas are each sunk deep into the blood-drenched ground of first-century Christianity, though today’s impressive structures stand proxy for their long-razed originals. If strong churches reflect a strong God, these Basilicas are all muscle.The present Basilica of St. Peter was dedicated, or consecrated, in 1626. It was under construction for more than one hundred years, was built directly over the tomb of the Apostle Peter, and considerably enlarged the footprint of the original Constantinian Basilica. That prior fourth-century Basilica was so decrepit by the early 1500s that priests refused to say Mass at certain altars for fear that the creaky building’s sagging roofs and leaning walls would collapse at any moment. The ancient Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls was consumed by a mammoth fire in 1823. The rebuilt Basilica was dedicated on December 10, 1854, just two days after Pope Pius IX had formally promulgated the dogma of Mary’s Immaculate Conception. The Basilica’s vast classical elegance is breathtaking—its marbled central nave stretches out longer than an American football field.The two Basilicas were, for centuries, linked by a miles-long, roofed colonnade that snaked through the streets of Rome, sheltering from the sun and rain the river of pilgrims flowing from one Basilica to the next as they procured their indulgences. Rome’s two great proto-martyrs were like twins tethered by a theological umbilical cord in the womb of Mother Church. The pope’s universal ministry was explicitly predicated upon these two martyrs. Rome’s apostolic swagger meant the Bishop of Rome’s headship was not merely symbolic but actively intervened in practical matters of church governance throughout Christendom. The pope, the indispensable Christian, was often depicted in early Christian art as a second Moses, a law-giver, who received from Christ the tablets of the New Testament for the new people of God.At intervals of five years, every diocesan bishop in the Catholic Church is obligated to make a visit “ad limina apostolorum”—“to the threshold (of the tombs) of the apostles.” This means they pray at the tombs of Saints Peter and Paul in Rome and personally report to Saint Peter’s successor. These visits are a prime example of the primacy of the pope, which is exercised daily in a thousand different ways, a core duty far more significant than the pope’s infallibility, which is exercised rarely. There is no office of Saint Paul in the Church. When Paul died, his office died. Everyone who evangelizes and preaches acts as another Saint Paul. But the barque of Peter is still afloat in rough seas, pinned to the stout tombs which, like anchors, hold her fast from their submerged posts under today’s Basilicas. A church is not just a building, any more than a home is just a house. A church, like a home, is a repository of memories, a sacred venue, and a corner of rest. On today’s feast, we recall that certain churches can also be graveyards. Today’s Basilicas are sacred burial grounds, indoor cities of the dead, whose citizens will rise from beneath their smooth marble floors at the end of time, like a thousand suns dawning as one over the morning horizon.Holy martyrs Peter and Paul, your tombs are the sacred destinations of many pilgrimages to the eternal city. May all visits to the Basilicas dedicated to your honor deepen one’s love and commitment to Mother Church.

November 17: Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, Religious1207–1231Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhitePatron Saint of the Third Order of Saint FrancisA faithful wife loses her husband and becomes a FranciscanThe marriage of today’s saint was not any less happy for being arranged. Elizabeth of Hungary’s parents betrothed her at the age of four to a young German nobleman named Ludwig and sent her away as a child to live in his family’s court. Elizabeth wed Ludwig when she was fourteen and he twenty-one. Only in a post-industrial age have the teenage years been understood, in some countries but not all, as a time of self-discovery, boundary pushing, rejection of tradition, and excuse for total confusion. Puberty, not the entire span of the teen years, was historically understood as the passage to adulthood, responsibility, and a professional life. It was typical of her era, and of many other eras too, that Elizabeth would marry at fourteen. She was ready and became a contented, serious, and successful wife and mother, bearing three children, while still a teen.Before Ludwig left on Crusade in 1227, he and Elizabeth vowed never to remarry if one were to die before the other. Then Ludwig died on his way to the Holy Land. Elizabeth was distraught but fulfilled her promise. So at the age of twenty, her already pious and prayerful soul waded into deeper Christian waters. Her mortifications became more rigorous, her financial generosity more total, and her prayer time more all consuming. Most of all, Elizabeth’s life now began to revolve almost uniquely around the poor, the aged, and the sick. She opened a hospice near a relative’s castle and there welcomed anyone in need.Elizabeth also fell under the spell of a charismatic and over-bearing spiritual director who insisted that she make the most severe emotional and physical sacrifices in her quest for perfection. As a sign of her commitment to the poor, and to aid her in conquering herself, Elizabeth took the habit of a Third Order Franciscan in 1227. Franciscanism was spreading like wildfire throughout Europe, and Elizabeth was not the only noblewoman far from Assisi to be drawn to the message of Saint Francis so soon after his death. A native Hungarian, who came in search of Elizabeth in Germany at this time, was shocked to find her dressed in drab grey clothes, poor, and sitting at a spinning wheel in her hospice. He begged Elizabeth to return to her father’s royal court in Hungary. She refused. She would stay near the tomb of her husband, stay near her children, now in the care of nuns and relatives, and stay close to the poor whom she loved so much.Most likely worn out by her austerities and near constant contact with the sick, Elizabeth died at the age of twenty-four on November 17, 1231. Miracles were attributed to her intercession soon after her burial, and testimonies to her holiness were collected so rapidly that she was canonized by the pope just four years after her death. In 1236 a shrine was dedicated to her memory in Marburg, Germany, and her remains were transferred there amidst great ceremony. Pilgrims continued trekking to her shrine throughout the middle ages, until a Lutheran prince, full of dissenting Protestant spit and vinegar, removed Elizabeth’s relics from her shrine in 1539. They have never been recovered.Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, we seek your heavenly intercession on this date of your early death. Help all young mothers to persevere in their vocations and all young widows to not despair but to be confident as they walk forward in life, knowing that Christ is at their side.

November 16: Saint Gertrude, Virgin 1256–1302Optional Memorial; Liturgical Color: White Patron Saint of nuns and of the Diocese of Magdeburg, GermanyIncandescent visions of Christ drew her into the deepToday’s saint, known as Saint Gertrude the Great, is one of the most provocative spiritual writers in the long and rich history of the Church. When just a child, she was placed in the care of Benedictine nuns, perhaps because of her parents’ early deaths. The high walls surrounding the cloister broadened the young girl’s mind, instead of confining it. For Gertrude, as for so many women of her era restricted by custom to narrow cultural lanes, a monastery-sponsored education amidst a self-governing community of women was superior to the forms of life otherwise available to them. Gertrude flourished in religious life and became well versed in the humanities, theology, and Latin, a language which she showed mastery of in her spiritual writings. At the age of twenty-five, Sister Gertrude had a jarring spiritual experience which would divide her life dramatically into two halves, “before” and “after.” “Before,” Gertrude was a faithful nun but overly interested in secular writers and knowledge for knowledge’s sake. “After,” she buried her head in Scripture, read widely in the Fathers of the Church, and melted under the high-amperage gaze beaming at her from the eyes of Christ.Gertrude struggled to convey in words the richness of her spiritual experiences. A distillation of her visions covers five volumes known in English as the Revelations of Saint Gertrude. Metaphors, adjectives, and other superlatives flow from our saint’s pen on page after page as she tries to capture the incandescent mystery of what she sees, hears, and feels. In a heavy, syrupy style common to her era, Saint Gertrude oozes about the intense love of Christ for mankind as symbolized by His Sacred Heart. More than three centuries before the visions of Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque in France, Saint Gertrude had visions of the Sacred Heart of Jesus! In one vision, Saint John the Evangelist placed Gertrude close to Christ’s wounded side, where she could feel His pulsating heart. Gertrude asks John why he did not reveal the mystery of Christ’s loving heart to mankind. Saint John responds that his duty was to reveal the very person of Christ, but it was for later ages, colder and more arid in their love of God, to discover His Sacred Heart.Gertrude lived a “nuptial mysticism” in which she was Christ’s bride and the Mass was the wedding banquet at which a chaste self-giving consummated the sacred bond of lover and beloved. Gertrude’s vowed virginity was the proof and basis of her enduring commitment to Christ, a promise made in the company of His mother, Mary, and all the angels and saints. Gertrude composed her spiritual diaries at the express command of her spouse, Christ. Their hymns, prayers, and reflections also show a profound concern for the holy souls in purgatory. Gertrude continually begged Christ’s mercy on them, and Christ responded that merely petitioning for the release of such souls was sufficient for Him to grant the favor.In Gertrude’s visions, Jesus speaks to her almost exclusively at Mass and during the Liturgy of the Hours. This is consoling. Most Catholics meet Christ more through the Sacraments than through books, so Christ appearing in priestly vestments, holding a chalice, or standing at an altar is absolutely congruent with our experience of Sunday Mass. Apart from her writings, few details of Gertrude’s life are known. She left virtually no footprint besides her life of quiet fidelity as a contemplative nun. Like John the Baptist, she decreased so the Lord could increase. Gertrude’s alluring private revelations became common spiritual reading among the saints of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and continue to fire the imagination of all who read them today.Saint Gertrude, as we turn the pages of your mystical revelations, we meet the true Christ, so powerful yet so close to us in His Sacred Heart. May we respond as you did to Jesus’ invitation and dedicate our lives totally to Him.

November 16: Saint Margaret of Scotlandc. 1045–1093Optional Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhitePatron Saint of Scotland, large families, and parents who have lost childrenA foreign-born royal becomes queen and inspires by her refinement and devotionIn the early eleventh century, a Danish Viking named Canute reigned as King of England. Canute exiled his potential rivals from an Anglo-Saxon royal family. One of these exiles, Edward, made his way to Hungary, married, and had a daughter named Margaret who grew up in a well-educated, royal, Catholic home. Margaret’s father eventually returned to England at the request of the king, his uncle Saint Edward the Confessor, and he brought his family with him, including Margaret. But Edward died shortly after coming home, leaving Margaret fatherless, and then Edward the Confessor died without an heir. War broke out. In 1066 at the Battle of Hastings, the Anglo-Saxon English lost to the Norman French. Margaret and her siblings were displaced to Scotland, far away from French efforts to eradicate Anglo-Saxon royals who had claims to the English throne. Thus was the circuitous route by which a woman of English blood who grew up in Hungary is commemorated today as Saint Margaret of Scotland.Saint Margaret was known to her contemporaries as an educated, refined, and pious woman. She married a Scottish King named Malcolm who was far more rustic than herself. He could not even read. The earliest Life of Margaret, written by a monk who personally knew her, states that Malcolm depended on his wife’s sage advice and admired her prayerfulness. According to Margaret’s biographer, Malcolm saw “that Christ truly dwelt in her heart...What she rejected, he rejected...what she loved, he, for love of her, loved too.” Malcolm embellished Margaret’s devotional books with gold and silver. One of these books, a selection of Gospel passages with illuminated miniatures of the four Evangelists, is preserved in an English museum. King Malcolm and Queen Margaret, along with their six sons and two daughters, truly created a domestic church centered on Christ. One son, David, became a national hero as King of Scotland and is popularly referred to as a saint.Margaret’s presence infused the unsophisticated, rural, Scottish court with culture. She brought her more Roman experiences of Church life with her to Scotland, and so pulled the Scottish Church into conformity with Roman and continental practice regarding the dating and observance of Lent and Easter. She encouraged the faithful to more fully observe Sunday by not working and, like so many medieval royals, she was also a prolific foundress of monasteries, including one she intended to be the burial place for Scottish kings and queens. Margaret was known for her concern for the poor, for dedicating hours a day to prayer and to spiritual reading, and for her great skill in embroidering vestments and church linens.Saint Margaret died, not yet fifty years old, just a few days after she was informed that her husband and son were killed in battle. Margaret and Malcolm were buried together under the high altar of a monastery. Devotion to the holy queen began soon after her death, and she was canonized in 1250.Saint Margaret of Scotland, you were the model of a virtuous queen who cared for both the spiritual and material welfare of your people. Inspire all leaders to give personal witness to holiness so that, through their leadership role, they inspire their people to be more virtuous.

November 15: Saint Albert the Great, Bishop and Doctorc. 1206–1280Optional Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhitePatron Saint of natural scientistsHe knew everything, taught Aquinas, and placed his complex mind at the Church’s serviceSaint Francis de Sales wrote that the knowledge of the priest is the eighth Sacrament of the Church. If that is true, then today’s saint was a sacrament unto himself. There was little that Saint Albert did not know and little that he did not teach. His mastery of all the branches of knowledge of his age was so manifest that he was called “The Great” and the “Universal Doctor.”Albert was born in Germany and educated in Italy. During his university studies, he was introduced to the recently founded Dominican Order and joined their brotherhood. While continuing his long course of formal studies, Albert was sent by his superiors to teach in Germany. He spent twenty years as a professor in various religious houses and universities until he finally obtained his degree and began to teach as a master in 1248. His most famous student was the Italian Dominican Thomas Aquinas, whose rare intellectual gifts Albert recognized and cultivated. Albert was also made the Prior of a Dominican Province in Germany, was a personal theologian and canonist to the Pope, preached a Crusade in Germany, and was appointed the Bishop of Regensburg for less than two years before resigning. Albert was neither ruthless nor politically minded, and the complex web of elites who had interests in his diocese required a bishop to display a sensitivity to power relationships which was not among Albert’s skills.After his short time as a diocesan bishop, Albert spent the rest of his life teaching in Cologne, punctuated by travels to the Second Council of Lyon in 1274 and to Paris in 1277 to defend Aquinas from his theological enemies. Albert’s complete works total thirty-eight volumes on virtually every field of knowledge known to his age: scripture, philosophy, astronomy, physics, mathematics, theology, spirituality, mineralogy, chemistry, zoology, biology, justice, and law. Albert’s assiduous study of animals, plants, and nature was groundbreaking, and he debunked reigning myths about various natural phenomena through close personal observation. He devoured all the works of Aristotle and organized and distilled their content for his students, re-introducing the great Greek philosopher to the Western world forever and always. This life-long project of philosophical commentary was instrumental in grounding subsequent Catholic theological research on a wide and sturdy platform of critical thinking, which has been a hallmark of Catholic intellectual life ever since.Albert’s comprehensive approach to all knowledge contributed to the flourishing of the nascent twelfth-century institutions of learning known as universities. The “uni” in university implied that all knowledge was centered around one core knowledge—that of God and His Truth. The modern understanding is that a “multiversity” is merely an administrative forum in which numerous branches of knowledge spread out in pursuit of their separate truths unhinged from any central focus or purpose.Saint Albert’s prodigious mind never ceased to be curious. Every bit of knowledge which he culled led him to gather even more. His encyclopedic knowledge embraced reality itself as one sustained instance of God loving the world. No bifurcation, no subcategories, no “my truth” and no “your truth.” God was real and God was knowable. Reality and Truth were one for Albert and his era, and autonomous reason could be trusted to lead the honest, rational seeker to those eternal verities. Albert was beatified in 1622 and was canonized and named a Doctor of the Church in 1931.Saint Albert the Great, your knowledge of the sacred and physical sciences understood God as a total reality. Through your divine intercession, help the faithful to see reality not as divided but as an expression of the Trinitarian God, a knowable person who is accessible to reason.

November 13: Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini, Virgin (USA)1850–1917USA Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhitePatron Saint of immigrants and hospital administratorsIndomitable and charismatic, she moved mountains for GodThe hurricane of apostolic activity that was Mother Cabrini motored powerfully over the Atlantic Ocean, gathered force as it swept into the American heartland, and then rested there, perpetually oscillating, for almost three decades. A serene eye, though, hovered at the center of this low roar of activity. Mother Cabrini accomplished so much, so well, and so quickly, precisely because her soul rotated calmly around a fixed point, the immovable Christ. A peaceful focus on God in the morning rained down a storm of good works in the afternoon and evening.Frances Cabrini was the tenth child born into a rural but well-to-do family in Northern Italy. Her uncle, a priest, had a deep influence on her, as did the Daughters of the Sacred Heart, whose school she attended as a teen. After graduation, she petitioned for entrance into the Daughters and, later, the Conossian Sisters. But Frances’ tiny frame had never quite conquered the frailty resulting from her premature birth. These Orders needed robust women capable of caring for children and the infirm. Nuns did not take vows so they could take care of other nuns. So even an application from an otherwise stellar candidate like Frances was reluctantly rejected due to her ill health. Frances eventually obtained a position as the lay director of an orphanage. Her innate charisma pulled people toward her like a magnet, and soon a small community of women grew up around her to share a common religious life.As proof of her apostolic zeal, Frances added “Xavier” to her baptismal name in honor of the great missionary Saint Francis Xavier. She then founded a modest house, along with six other women, dedicated to serving in the Church’s foreign missions. Frances was clearly the leader and wrote the new Institute’s Rule. Eventually the small Order received Church approval as the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The sisters’ excellent work became well known, and in 1887 Mother Cabrini, the Superior, met with Pope Leo XIII in Rome to inquire about her sisters evangelizing in China. The Pope listened to her in silence and then concluded simply: Her mission was “not to the East, but to the West.” The plug had been pulled on entire regions of Italy and their populations drained away to the United States. They needed the Church’s attention.In 1889 Mother Cabrini left for the United States with six sisters. Disembarking from the ship in New York Harbor, they were met by not even a single person. No one expected them, and no one welcomed them. The Archbishop was cold and told Mother Cabrini that he wanted Italian priests, not sisters, and that her ship was still docked in the harbor if she wanted to return to Italy. She replied “I have letters from the Pope” and stayed and persevered amidst the most extreme hardships.Starting from absolute zero, Mother Cabrini miraculously began her work among Italian immigrants. She would work almost exclusively with, and for, Italians the rest of her life. She begged, pleaded, and cajoled. She pulled every lever of charm and persuasion she could reach. It worked. Her deep spirituality and constant state of motion soon put her in contact with Italian benefactors eager to help their own. Mother Cabrini was then seemingly everywhere, doing everything. She founded hospitals, orphanages, schools, workshops, and convents in New York, Denver, Cincinnati, Pittsburg, St. Louis, San Francisco, and Chicago. She trekked to Nicaragua, Argentina, and Brazil. She sailed back to Italy nine times. She became an American citizen but remained fully Italian in her identity and a source of pride for America’s many “Little Italies.” Mother Cabrini’s relentless energy, remarkable administrative skills, shrewdness, humility, and charisma quickly built an empire of charity. When she died in Chicago, she left behind sixty-seven institutions and a robust Order of dedicated nuns. On July 7, 1946, she became the first United States citizen to be canonized a saint.Mother Cabrini, you were indefatigable in your work for Christ and the Church. You knew no rest, no stranger, and no obstacle that could not be overcome. Inspire all evangelizers and teachers to be so brave and tireless in their service.

November 12: Saint Josaphat, Bishop and Martyr1580–1623Memorial; Liturgical Color: RedPatron Saint of reunion between Orthodox and CatholicsA holy bishop is murdered for unifying East and WestSaint Josaphat died for something few in his era died for—ecumenism. In fact, the word ecumenism did not even exist when Josaphat was martyred. Josaphat was born in Ukraine but grew to manhood working a trade in Vilnius, Lithuania. In his late teens, he felt called to be a monk, so he rejected an offer of marriage and joined a monastery in Vilnius in 1604. Josaphat’s austerities, intelligence, and prayerfulness made him a natural leader, and he was duly ordained a deacon and priest and earned a reputation as an effective preacher.But it was a historic decision by Orthodox religious leaders, about ten years before Josaphat became a monk, that would bend the arc of his life and eventually lead to his death. In 1595 the Orthodox Metropolitan of Kiev and five other Orthodox bishops representing millions of Ruthenian (Ukrainian and Belarusian) faithful met in the city of Brest and signed a declaration of their intention to enter into union with the Bishop of Rome. The Pope accepted their conversion from Orthodox to Catholic, while allowing them to keep their Byzantine liturgical rites and traditions. The Union of Brest was a one-of-a-kind event. Yet it triggered Orthodox violence and bitterness toward the Catholic Church which has endured into modern times.Josaphat joyfully embraced the entrance of his native Orthodox faith into the Catholic fold. But he also insisted that the Eastern traditions of his pan-Slavic people should perdure, and be respected, while his people ecclesiastically migrated into the paddock of the Roman Pontiff. Unity, yes. Uniformity, no. The Church, historically, had long been composed of various liturgical traditions reflecting its numerous cultures. The Latin Rite, though, eventually predominated as Western nations grew stronger and colonized huge chunks of the world. The Union of Brest’s careful balance of accepting theological and jurisdictional unity with Rome while insisting on liturgical distinctiveness was confusing to many of the faithful Slavic peasants of Northeastern Europe. Nonetheless, when Josaphat was named a Bishop in present day Belarusia, he continued to champion the union with Rome with all his considerable powers and was largely successful in curtailing Orthodox clergy from exercising ministry in his diocese.Because he represented something new, an Eastern Rite Catholic, Josaphat was misunderstood by his co-religionists who should have supported him the most, particularly Polish and Lithuanian bishops and princes. The tensions of the time came to a head when an Orthodox bishop established a competing diocesan and parish structure alongside that of Josaphat’s diocese and parishes. The faithful experienced two church structures that were virtually identical in their liturgy but divergent in their leaders and lines of authority. In response to Orthodoxy’s aggressive incursion into his ecclesial territory, Josaphat put his usual vigor into preaching and teaching the importance of union with Rome. But in 1623, while seeking to stop an Orthodox priest from secretly ministering in his jurisdiction, Josaphat was ambushed by Orthodox faithful who conspired with their leaders to rid themselves of this thief of souls. Saint Josaphat was brutally attacked by a mob, his head was cleaved by an axe, and his body dumped into a river. Josaphat was beatified in 1643 and canonized in 1867. In the twentieth century, Josaphat’s remains were brought to Rome and buried under the altar of Saint Basil in St. Peter’s Basilica.Saint Josaphat, you gave your life attempting to bring East and West together. Give us your spirit of unity so that our prayers bring all Christians into common union under the leadership of a common head, the successor of Saint Peter.

November 11: Saint Martin of Tours, Bishopc. 336–397Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhitePatron Saint of France, soldiers, and conscientious objectorsHe gave away half of his cloak and then all of his life Many great and holy men and women are unknown to history because they lacked the one crucial ingredient to become well known—a biographer. Today’s saint was one of the fortunate ones. A historian named Sulpicius Severus personally knew and interviewed Martin in the last years of Martin’s life and put it all on parchment. In an age of few books, Sulpicius’ Life of Saint Martin was a blockbuster. Over many decades and centuries, it slipped into the bloodstream of European culture until, by the medieval age, the Life was standard reading in all monasteries. Virtually every priest and monk in Europe was deeply familiar with the details of the life of Saint Martin of Tours.The typical biography of a saint for the first few centuries of Christianity worked from the back to the front, from death to life. The real drama was how the saint died, not how he or she lived. Tales of bloody martyrdom, solitary exile, starvation and exposure were as moving and unfortunate as they were common. The Life of Saint Martin told of Martin’s adventures and heroism in living the faith, not just about his last few breaths. He was a saint for the new age of legalized Christianity. Martin of Tours died in his bed.Martin was born to pagan parents in present-day Hungary but desired to become a Christian from a young age. His father resisted his son’s holy desires and obliged Martin to follow in his footsteps and serve as a soldier in Rome’s Imperial Guard. Martin was serving in France when the most iconic moment of his life took place. Martin was slowly approaching the city gates of Amiens on horseback one cold winter evening. A half-naked man shivered on the ground, begging for help. No one stopped. No one helped. No one cared. So Martin, clad as a soldier, pulled the cloak from his back, drew his sharp sword from its scabbard, and sliced his cloak in two. The poor man’s skeletal frame was covered with just half of the cloak. That same night, when Martin fell asleep, he had a dream. Jesus appeared to him clad in the cloak and said “Martin, still a catechumen, covered me with this garment.” Upon awakening, Sulpicius tells his reader, “Martin flew to be baptized.”Martin subsequently befriended one of the great men of Gaul of that era, Saint Hilary of Poitiers, who ordained him into minor orders. After various apostolic adventures, Martin was chosen the Bishop of Tours in 372. In his twenty-five years as bishop, Martin was zealous, and jealous, for the House of the Lord. He aggressively tore down pagan temples, which he understood to be dedicated to demons. He traveled incessantly and was untiring in evangelizing the people of the countryside of Gaul and in founding churches. Martin also developed a reputation as a miracle worker and prophet. He cured the eye problems of Saint Paulinus of Nola, Saint Augustine’s good friend.By the time of his peaceful death, Bishop Martin of Tours had a well-deserved reputation for holiness. Devotion to Martin spread as Sulpicius’ biography was copied and shared. Numerous churches were named in Martin’s honor in every country of Europe. England had one hundred seventy-three churches dedicated to Martin of Tours in 1800. The Shrine over Martin’s tomb was one of the most popular pilgrimage destinations in all of Europe until France was riven by Reformation violence in the 1560s. In an interesting vestige of Martin’s enduring historic importance, Martin’s feast day in the Breviary is more fully elaborated with prayers and antiphons than almost any comparable saint on the Church’s calendar.Saint Martin of Tours, your encounter with the beggar has fired the imagination of countless Christians. You were generous in every single way in living your faith. Through your intercession in heaven, assist us now to see Jesus in everyone, just as you did then.

November 10: Saint Leo the Great, Pope and DoctorLate Fourth Century–461Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhitePatron Saint of popes and confessorsA Pope vigorously exercises his universal ministry and defines Christ’s divinityHistory has so far conferred on just two popes the title of “Great,” and today’s saint is one of them. Leo the Great’s origins are obscure, so nothing is known with certainty of his early life. He was, though, ordained into Holy Orders and rose to prominence as a papal advisor in the 420s. He corresponded with imminent theologians and acted as a papal emissary before he was elected Bishop of Rome in 440. Leo was a pope’s pope. He expanded the power and influence of the papacy at every opportunity. The Church’s earliest theological tradition rooted Rome’s primacy in the double martyrdom of Saints Peter and Paul in the eternal city. No other city could claim to have been sanctified by the blood of two martyrs. Pope Leo, however, emphasized what was to become a more dominant argument for papal supremacy—that the pope’s authority is not rooted merely on the historical fact that Peter and Paul died on roman ground but on the theological fact that the Bishop of Rome occupies the Chair of Saint Peter.By word and action, Leo repeatedly taught that the pope’s power was unequaled and without borders, that the pope was the head of all the world’s bishops, and that every bishop could have direct recourse to the pope, and not just to the local archbishop, in disputed matters. Pope Leo thus accelerated an existing tendency consolidating church governance and authority under a Roman umbrella. Regional or even local decision-making by individual dioceses or groups of dioceses did occur. But in important theological, moral, or legal matters that affected the entire church, every bishop rotated in a steady orbit within the powerful gravitational field of Rome. Pope Leo also enacted a more aggressive papal role directly overseeing and enforcing discipline over bishops, intervening in and settling disputes. The Catholic Church is not an international federation of dioceses, after all. It needs a strong center of gravity to ensure that centrifugal forces do not unwind the universal church into a galaxy of independent national churches, united in name only.Nowhere was Leo’s authority exercised more clearly and successfully than at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. The theological issue at stake concerned Christ’s divinity. Some theologians in the East were espousing the Monophysite heresy, which argued that Christ had only one divine nature. The Council consisted of six hundred bishops from the Eastern Roman Empire, with a handful from Africa. Leo sent three legates from Italy who were treated with all honor and respect as representatives of Peter’s successor. They read out loud to the Council Fathers the “Tome of Leo” on the Incarnation. The pope’s words laid out, with force, clarity, and eloquence, that Jesus Christ had both a divine and a human nature “without confusion or admixture.” When the legates finished reading, the bishops’ common response to the pope’s words was “This is the faith of the fathers; this is the faith of the apostles… Let anyone who believes otherwise be anathema. Peter has spoken through the mouth of Leo.” The Tome of Leo from then on became the teaching of the Catholic Church. If Christ were not truly man, or not truly God, the babe in the manger would be just another child whose birth was no more worthy of celebration than that of Julius Cesar, Gandhi, or Marco Polo. Pope Leo saved Christmas.In 452 Pope Leo entered the history books when he rendezvoused with Attila the Hun in Northern Italy, convincing him not to sack Rome. A legend says that Attila turned back because he saw Saints Peter and Paul standing right behind Leo. Pope Leo governed the Church as the Western Roman Empire was slowly disintegrating. He was courageous in alleviating poverty, protecting Rome from invaders, and maintaining Rome’s Christian heritage. While outstanding as an effective and practical leader, Pope Leo is most known for the concision, depth, and clarity of his sermons and letters, for which he was declared a Doctor of the Church in 1754. He was the first pope, after Saint Peter himself, buried in Saint Peter’s Basilica. His remains lie under a beautiful marble relief sculpture of his famous meeting with Attila.Pope Saint Leo the Great, give to the Pope and all bishops pastoral hearts, sharp minds, and courageous wills, so that they may lead the Church by personal example, by correct teaching, and by their caring little for worldly criticism.

November 9: Dedication of the Lateran BasilicaFeast; Liturgical Color: WhiteA venerable basilica is the mother of all churchesIn the eighth chapter of his Confessions, Saint Augustine relates the story of an old and learned Roman philosopher named Victorinus. He had been the teacher of many a Roman senator and nobleman and was so esteemed that a statue of him was erected in the Roman Forum. As a venerable pagan, Victorinus had thundered for decades about the monster gods, dark idols, and breathless demons in the pantheon of paganism. But Victorinus assiduously studied Christian texts and whispered to a friend one day, “You must know that I am a Christian.” The friend responded, “I shall not believe it…until I see you in the Church of Christ.” Victorinus responded mockingly, “Is it then the walls that make Christians?” But in his grey hairs, Victorinus finally did pass through the doors of a Catholic church to humbly bow his head to receive the waters of Holy Baptism. There was no one who did not know Victorinus, and at his conversion, Augustine writes, “Rome marveled and the Church rejoiced.”A church’s walls do not make one a Christian, of course. But a church has walls nonetheless. Walls, borders, and lines delimit the sacred from the profane. A house makes a family feel like one, a sacred place where parents and children merge into a household. A church structurally embodies supernatural mysteries. A church is a sacred space where sacred actions make Christians unite as God’s family. Walls matter. Churches matter. Sacred spaces matter. Today the Church commemorates a uniquely sacred space, the oldest of the four major basilicas in the city of Rome. The Lateran Basilica is the Cathedral of the Archdiocese of Rome and thus the seat of the Pope as Bishop of Rome.A basilica is like a church which has been made a monsignor. Basilicas have certain spiritual, historical, or architectural features by which they earn their special designation. Considered only architecturally, a basilica is a large, rectangular, multi-naved hall built for public gatherings. When Christianity was legalized, its faithful spilled out of their crowded house churches and into the biggest spaces then available, the basilicas of the Roman Empire. If Christians had met in arenas, then that word would have been adopted for ecclesial usage instead of basilica.The Laterani were an ancient Roman noble family whose members served several Roman Emperors. The family built a palace carrying their name on a site which in the fourth century came into the possession of the Emperor Constantine, who then turned it over to the bishop of Rome. An early pope enhanced and enlarged the basilica style palace into a large church, which, in turn, became the oldest and most important papal church in the eternal city. The popes also began to personally reside in the renovated Lateran palace. By medieval times, the Basilica was rededicated to Christ the Savior, Saint John the Baptist, and Saint John the Evangelist. The popes lived at the Lateran until the start of the Avignon papacy in present day France in 1309.With the Avignon papacy ensconced far from Rome for seven decades, the Lateran Basilica was damaged by fires and deteriorated so sadly that by the time the popes returned to Rome in 1377, they found the Basilica inadequate. An apostolic palace was eventually built next to St. Peter’s Basilica on the Vatican hill and has been the seat of the successors of Saint Peter ever since. The Lateran Basilica retains its venerable grandeur, despite now being a baroque edifice with only a few architectural traces of its ancient pedigree. Beautiful churches are like precious heirlooms passed down from one generation to the next in God’s family. Walls do not make us Christians, but walls do clarify that certain sacred rituals are practiced in certain sacred spaces and in no others. A family in its home. A judge in his court. A surgeon in her operating room. An actor on his stage. God on His altar. We come to God to show Him the respect He deserves. He is everywhere, yes, but He is not the same everywhere. And we are not the same everywhere either. We stand taller and straighter when we step onto His holy terrain.Heavenly Father, we praise You more worthily when we are surrounded by the holy images in Your holy churches. Through Your grace, inspire us to render You due homage in the houses of God where Your presence burns brighter and hotter than anywhere else.

November 4: Saint Charles Borromeo, Bishop1538–1584Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhitePatron Saint of bishops, cardinals, and seminariansA young nobleman becomes a Cardinal, exemplifies holiness, and reforms the ChurchToday’s saint was born in a castle to an aristocratic family. His father was a count, his mother a Medici, and his uncle a pope. This last fact was to determine the trajectory of Charles Borromeo’s entire life. Pope Pius IV (1559–1565) was the brother of Charles’ mother. At the tender age of twelve, Charles received the external sign of permanent religious commitment, the shaving of the scalp known as tonsure. He was industrious and extremely bright and received advanced degrees in theology and law in his native Northern Italy. In 1560 his uncle ordered him to Rome and made him a Cardinal at the age of just twenty-one, even though Charles was not yet ordained a priest or bishop. This was brazen nepotism. But in this instance it was also genius. The Cardinal-nephew was a man of rare gifts, and his high office afforded him a wide forum to give those gifts their fullest expression.At the Holy See, Charles was loaded down with immense responsibilities. He oversaw large religious orders. He was the papal legate to important cities in the papal states. He was the Cardinal Protector of Portugal, the Low Countries, and Switzerland. And, on top of all this, he was named administrator of the enormous Archdiocese of Milan. Charles was so bound to his Roman obligations, however, that he was unable to escape to visit Milan’s faithful who were under his pastoral care. Non-resident heads of dioceses were common at the time. This pained Charles, who would only be able to minister in his diocese years later. Cardinal Borromeo was a tireless and methodical laborer in the Holy See, who nevertheless always found ample time to care for his own soul.When Pope Pius IV decided to reconvene the long-suspended Council of Trent, the Holy Spirit placed Cardinal Borromeo in just the right place at just the right time. In 1562 the Council Fathers met once again, largely due to the energy and planning of Charles. In its last sessions, the Council completed it most decisive work of doctrinal and pastoral reform. Charles was particularly influential in the Council’s decrees on the liturgy and in its catechism, both of which were to have an enduring and direct influence on universal Catholic life for over four centuries. Charles was the driving force and indispensable man at the Council, yet he was still just in his mid-twenties, being ordained a priest and bishop in 1563 in the heat of the Council’s activities.In 1566, after his uncle had died and a new pope granted his request, Charles was at last able to reside in Milan as its Archbishop. There had not been a resident bishop there for over eighty years! There was much neglect of faith and morals to overcome. Charles had the unique opportunity to personally implement the Tridentine reforms he had played such a key role in writing. He founded seminaries, improved training for priests, stamped out ecclesiastical bribery, improved preaching and catechetical instruction, and combatted widespread religious superstition. He became widely loved by the faithful for his personal generosity and heroism in combating a devastating famine and plague. He stayed in Milan when most civil officials abandoned it. He went into personal debt to feed thousands. Charles attended two retreats every year, went to confession daily, mortified himself continually, and was a model Christian, if an austere one, in every way. This one-man army for God, this icon of a Counter-Reformation priest and bishop, died in Milan at the age of forty-six after his brief but intense life of work and prayer. Devotion to Charles began immediately, and he was canonized in 1610.Saint Charles Borromeo, your personal life embodied what you taught. You held yourself and others to the highest standards of Christian living. From your place in heaven, hear our prayers and grant us what we ask, for our own good and that of the Church.

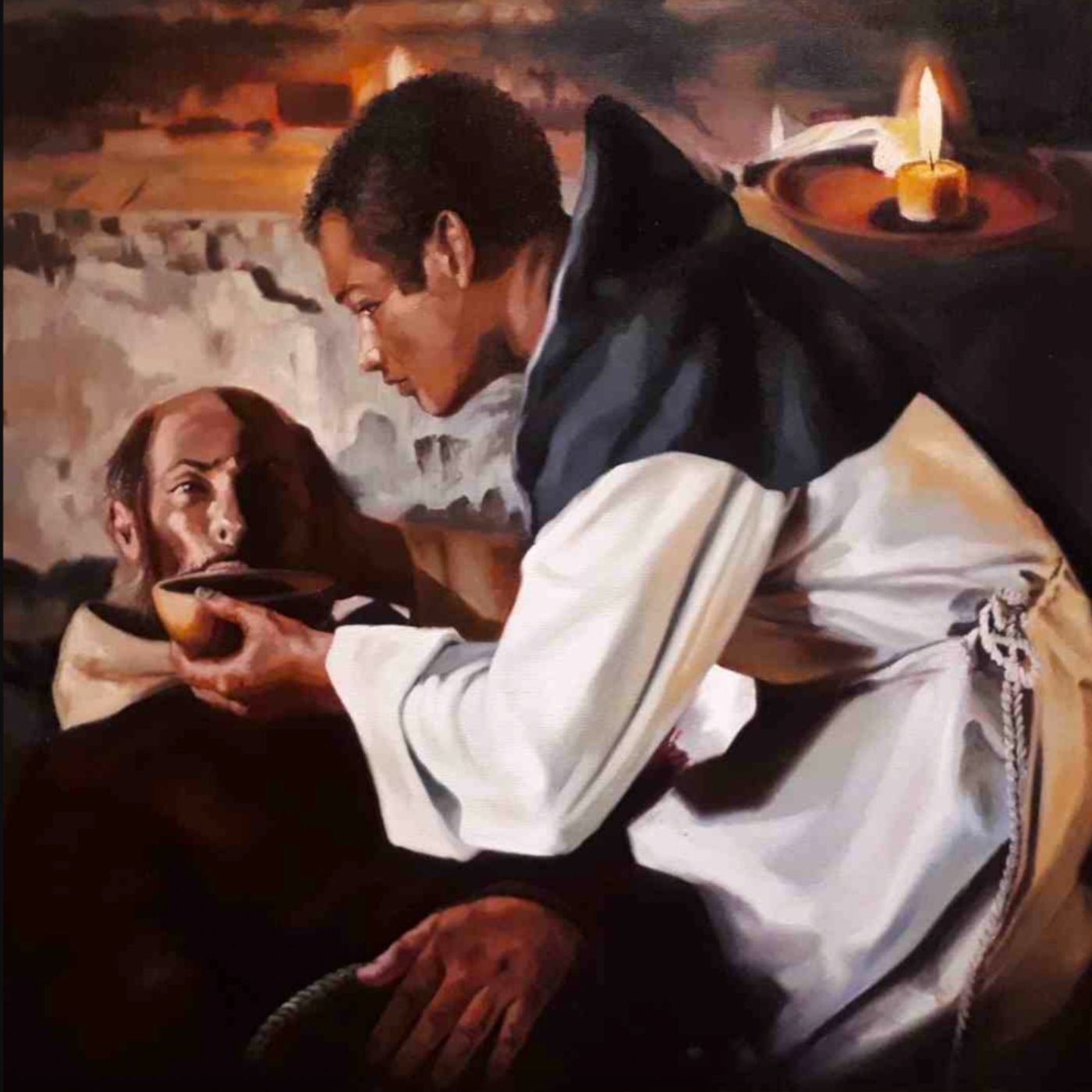

November 3: Saint Martin de Porres, Religious1575–1639Optional Memorial; Liturgical Color: WhitePatron Saint of mixed-race peoples and barbersA humble, mixed-race Dominican brother works miraclesToday’s saint was born in colonial Lima, Peru, to a well-connected Spanish father and a black Panamanian mother who had been a slave. While parentage is revealing, focusing uniquely on someone’s origins can also be a lazy shortcut which reduces a complex person to mere bloodlines, leaving aside a thousand more compelling factors that make a life interesting. It would be difficult, however, to overemphasize just how much Martin de Porres’ mulatto origins (Spanish and black) impacted his life. Even though his father was perfectly well known, Martin’s baptism registration reads “Son of an unknown father,” making Martin illegitimate, a severe disadvantage. To be half black in colonial Latin America was to start life’s race ten miles behind. Catching up to the Spanish-born colonists (Peninsulares) or to the locally born pure-blood Spanish (Criollos) would be impossible. On the many-runged ladder of social acceptability in the Spanish colonies, Martin was just above an African slave.Martin’s father did make sure, however, that his son received a good education and enrolled him as a barber-surgeon apprentice in Lima. Martin learned how to set fractures, dress wounds, and treat infections according to the best practices of his era. And from his mother, he learned some unconventional herbal remedies that rounded out his more traditional medical education. These skills would hold Martin in good stead throughout his life. He treated the sick and injured regularly and, over time, earned a reputation as an extraordinary healer. He aided in founding a hospital and orphanage in Lima, distributed food to the poor, and cared for recently arrived African slaves. His extraordinary charity was his greatest attribute. You need candles? Of course. Blankets? One moment, please. Shoes and a comb? I’ll be back. Miracles and cures? Yes, God bless you. Martin de Porres became famous for doing many things—very many things—and doing them all well and with a smile.In addition to his life of interrupted service, Martin was also a spiritual warrior. He became a Dominican lay brother but never a priest. He lived in community and proudly wore the Dominican habit. He had a self-deprecating sense of humor that jokingly acknowledged his lowly mulatto status. He abstained from meat, spent long hours in prayer before the Blessed Sacrament, and was witnessed displaying supernatural gifts. He levitated. He bilocated. His room filled with light. He possessed knowledge he could in no way have possessed naturally. His wide array of natural and supernatural gifts made him famous in Lima. When his life came to an end at the age of sixty, his body was publicly shown, and pieces of his habit were discreetly clipped off as relics.Martin de Porres, canonized in 1962, was among the first generation of saints from the New World, along with his contemporaries Saints Rose of Lima and Turibius of Mogrovejo. Martin was also the first mulatto saint. He lived a traditionally pious spirituality in keeping with the medieval saints of Europe. But he was not from Europe, did not enjoy a European education, and did not have pure European blood. Saint Martin proved the Catholic Faith could migrate across the Atlantic Ocean intact. The ancient faith found a home in a mulatto soul. Catholicism had successfully made the passage to a new land and immediately drove its roots deep into that land’s native soil, converting a new mixed-race people to an old religion, making Jesus Christ the Lord of Latin America. Saint Martin de Porres was a harbinger of many good things to come.Saint Martin de Porres, we present our humble petitions to you, so that your faith and humility may bring them to our Father in Heaven. You were close to both God and man on earth. Continue to be close to us as you live with the Lord in heaven and seek favors on our behalf.