Discover Field Notes

Field Notes

144 Episodes

Reverse

The first archaeological evidence we have that points to organized observances of the winter solstice come from the Neolithic period—that era from about 12,000 to 6,500 years ago which hastened the Stone Age into those of Copper and Bronze

Seasonal camouflage and the consequences of transitioning color phase too early

Near Čmʔomʔotúlexʷ (Place of Smokey Land) or Yellowstone National Park, in -5-degree weather, I kneeled on my freshly skinned bison hide, which provided steaming warmth beneath me.

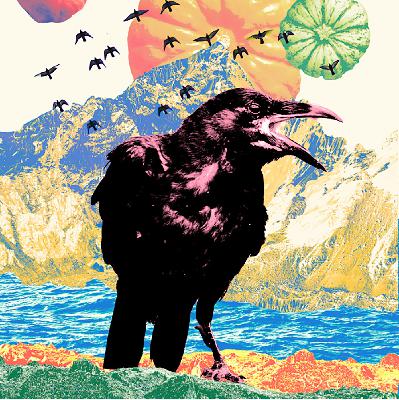

I like to talk to the crows, though I don’t know what we’re talking about. Researching the subject, I learned that they have over 250 different calls.

Summer brings more than blue skies and hot days to Montana. It’s during this time of the year that white-tailed deer fawns are born.

It was too soon for swirls of cascading autumn leaves, and the formation of this sudden dispatch had a certain energy to it. This orange blast of color moved with purpose.

Harriet the Osprey knew what was coming.

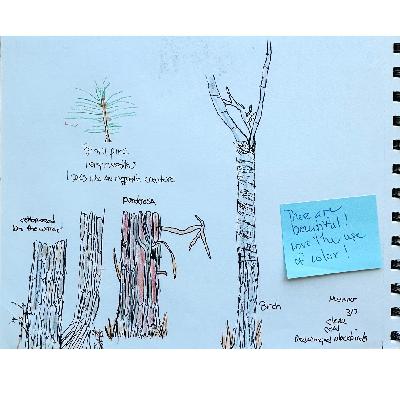

There is a pine needle on my kitchen table. There is a pine needle in my soul. If I could only put that on paper.

As the days grow shorter and nights turn cooler, I find myself drawn outdoors at sunset.

As I watched these mountain bluebirds, likely catching those pesky mosquitoes for their dinner, I felt a familiar comfort in their presence.

Fireweed’s vibrant flowers provide sweet nectar to native bees, flies, butterflies, and even honeybees, if their hive is nearby.

Oak gall ink was the most popular ink in Europe from the Middle Ages to the 19th century. The Book of Kells from A.D. 800, the Magna Carta, and the Declaration of Independence were all written in gall ink.

My eyes slowly followed the tree down to the base when I saw that my dog was carefully pulling the berries right off the branches and swallowing them down.

This amazing place has seen it all, from a giant sea to volcanoes and glaciers to today’s semi-arid desert.

Clueless as to what this was, I relied on a phone app for identification. Curlycup gumweed? Who came up with that creative name?

On the suggestion of an experienced birder, I bought a wire wreath and stuffed it with unshelled peanuts. The magpies spent hours skirmishing with each other to grab a peanut. I reveled in the mayhem.

There were tulip poplars, also known as yellow poplars or tulip trees. No tulip maples. I’d thought I’d seen the real thing in Washington, DC. No such beauties adorned my backyard.

Throughout history, people have been captivated by owls. There are 260 species of owls across the planet. They can be found on every continent except Antarctica.

I’ve always been fascinated by ruffed grouse. For such a small, skittish-seeming bird, they have a hugely outsized presence in the soundscape of the forest.

It’s easy to see how the nighthawks’ idiosyncrasies make them a crowd favorite, but what I love most about them are the cherished memories they resurrect.