Discover Ground Truths

Ground Truths

Ground Truths

Author: Eric Topol

Subscribed: 79Played: 364Subscribe

Share

© Eric Topol

Description

78 Episodes

Reverse

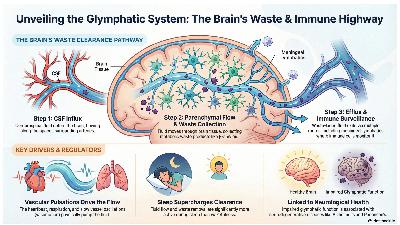

Jonathan Kipnis is a neuroscientist, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Pathology and Immunology at Washington University, St. Louis, who discovered meningeal lymphatics and has been a prolific researcher in brain drainage and the continuous immune system surveillance of the brain.I made this infographic with the help of Notebook LM to summarize many of the concepts we discussed. (Notebook LM is free and worth trying)We went over his new review with 24 co-author leading experts in the recent issue of NeuronA Clever Cover The drainage system anatomy on influx and efflux (blue arrows)The 3 ways the flow of glymphatics are modulated. I mentioned the recent studies that show atrial fibrillation, via reduced cardiac pulsation, has an effect on reducing glymphatic flow. We also discussed his recent review on the immune surveillance system in Cell:A schematic of key channels for the “faucet” and “drain” and how the system changes from healthy to central nervous system autoimmune diseases (such as multiple sclerosis) and aging with different immune bar codes.The outsized role of astrocytes in the brain, a subject of recent Nature feature, was also mentioned.Our understanding of the brain’s immune system has been completely revamped. Kipnis’s recent review in Nature Immunology highlights the critical role of the outer layers —the skull, dura and meninges—as an immune reservoir that is ready to detect and react abnormalities in the brain with a continuous “intelligence report.”Notably, Kipnis touched on lymphatic-venous anastomosis (LVA) surgery (Figure below) for Alzheimer’s disease which is popular in China, available at 30 centers in multiple cities, and the subject of multiple randomized trials as a treatment for Alzheimer’s. Trials of LVA surgery are also getting started in the United States for treatment of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Here is a Figure to show the surgical anastomoses (connections) from the deep cervical lymphatics to external jugular and internal jugular veinsThis podcast was packed with insights relevant to health, spanning sleep quality, sleep medications, autoimmune diseases, and Alzheimer’s disease. I hope you find it as informative and engaging as I did.A Poll************************************This is my 4-year anniversary of writing Ground Truths. Post number 250! That’s an average of more than 1 per week, nearly 5 per month. Hard for me to believe.Thanks to Ground Truths subscribers (approaching 200,000) from every US state and 210 countries. Your subscription to these free essays and podcasts makes my work in putting them together worthwhile. Please join!If you found this interesting PLEASE share it!Paid subscriptions are voluntary and all proceeds from them go to support Scripps Research. They do allow for posting comments and questions, which I do my best to respond to. Please don’t hesitate to post comments and give me feedback. Let me know topics that you would like to see covered.Many thanks to those who have contributed—they have greatly helped fund our summer internship programs for the past two years. It enabled us to accept and support 47 summer interns in 2025! We aim to accept even more of the several thousand who will apply for summer 2026Thank you EG, Alan, Lynn L, Stacy Mattison, Jackie, and many others for tuning into my live video with Jonathan Kipnis! Join me for my next live video in the app. Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

A recording from my enthralling conversation with Prof Matthew Cobb about the life and science contributions of Francis Crick, regarded as one of the most influential biologists of all times, along with Darwin and Mendel. As you’ll see, there’s so much more to Crick’s story than cracking DNA’s double helix structure in a matter of weeks with James Watson. Matthew Cobb, Emeritus Professor of the University of Manchester, has written several award-winning books on life science, but I think this is his most important one to date, deeply researched and a thrilling account of Crick’s life, clearing up, as best as one can, many questions, and presenting some surprises.The transcript is available (A.I. generated) by clicking at the top right.A few things we discussed—Crick’s reaction to James Watson’s bookCrick contrasted his own approach to science writing with Watson’s memoir: “The difference between my lecture and your book is that my lecture had a lot more intellectual content and nothing like so much gossip. (...) Your book on the other hand, is mainly gossip and I think it a pity in this way that there is so much of it that it obscures some of the important conclusions which can be drawn of what we did at the time”.—The Peyote Poem, by Michael McClure (part 1) that had a big influence on Crick—Crick’s 1994 neuroscience book “The Astonishing Hypothesis”“You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free Weill, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.”—CrickThe book has been reviewed at Science, Nature, The Economist and many other journals. Here is a gift link to The Economist It has deservedly been named a best book of 2025 by The Guardian, The Economist, and many other media.Thank you Bruce Lanphear, Harshi Peiris, Ph.D., Elisabetta Pilotti, Allan Konopka, Stephen B. Thomas, PhD, and over 500 others for tuning into my live video with Matthew Cobb! *********************Upcoming, this Wednesday 9AM PT, live podcastI will be interviewing Dan Buettner founder of the Blue Zones Join us!**********************Thanks to US News for recently being named one of the 25 best leaders in the United Stateshttps://www.usnews.com/news/leaders/articles/best-leaders-2025-eric-topol^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^Thanks to >190,000 Ground Truths subscribers from every US state and 210 countries. Your subscription to these free essays and podcasts makes my work in putting them together worthwhile.If you found this interesting PLEASE share it!Paid subscriptions are voluntary and all proceeds from them go to support Scripps Research. They do allow for posting comments and questions, which I do my best to respond to. Please don’t hesitate to post comments and give me feedback. Let me know topics that you would like to see covered.Many thanks to those who have contributed—they have greatly helped fund our summer internship programs for the past two years. It enabled us to accept and support 47 summer interns in 2025! We aim to accept even more of the several thousand who will apply for summer 2026. Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

A couple of weeks ago, the FDA Commissioner published a WSJ oped “The FDA Liberates Women’s Hormone Replacement Therapy” (←gift link) and, with other FDA colleagues, a JAMA essay entitled “Updated Labeling for Menopausal Hormone Therapy” (open-access). That change, and the data cited, led to a series of articles in the days that followed, such as at STAT News “FDA reverses decades-old warning on hormone therapy products for menopause. Agency says the treatments o!fer heart, brain, and bone health benefits” and at the Washington Post “The FDA finally corrects its error on menopause hormone therapy. Women have been needlessly scared away from effective treatments.” If you read through these links, you’ll be confused. Does MHT have proven cognitive benefits? What about a study from 1991 that showed ~50% reduction of fatal heart events with MHT? Or the 35% decreased risk of Alzheimer’s disease? Or the breast cancer increased risk attributed to medroxyprogesterone acetate?I turned to my go-to gynecologist truth teller, Dr. Jen Gunter, to get her review of the evidence. This is a complex topic, with old data from the 2002 Women’s Heath Initiative (WHI), new reports since, population level analysis, changes in preparations of MHT including local delivery, and much more.Here is our conversation which isn’t just about MHT but includes “Big Wellness” marketing direct to middle aged women, the new FDA approved drug for hot flashes, the $14 million cut of the NIH’s Office of Women’s Health , marked increase in philanthropic support of women’s health research, the Surgeon General nominee, ovarian failure, and a lightning round on proven benefits of MHT.Here’s a brief clip on her views of the women’s health “wellness” predatorsWe also discussed the reasons for Dr. Gunter’s planned move next year back to Canada after practicing gynecology for 3 decades in the United States. I referred to a recent GT I wrote about the WHI and the potential favorable impact of MHT on the immune system, as suggested by new data on organ clocks. That finding, which has been replicated, may be linked to healthy aging, extending healthspan.****************************Thanks to the >190,000 Ground Truths subscribers from every US state and 210 countries. Your subscription to these free essays and podcasts makes my work in putting them together worthwhile.If you found this interesting PLEASE share it!Paid subscriptions are voluntary and all proceeds from them go to support Scripps Research. They do allow for posting comments and questions, which I do my best to respond to. Please don’t hesitate to post comments and give me feedback. Let me know topics that you would like to see covered.Many thanks to those who have contributed—they have greatly helped fund our summer internship programs for the past two years. It enabled us to accept and support 47 summer interns in 2025! We aim to accept even more of the several thousand who will apply for summer 2026.Thank you Debbie Weil, Cynthia Brumfield, Sara Garcia, Harshi Peiris, Ph.D., Liane Moccia, and over 1,000 others for tuning into my live video with Dr. Jen Gunter! Join me for my next live video in the app. Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

Dr. Susan Monarez was the first CDC Director to be confirmed by the Senate and served from July 31, 2025 – August 27, 2025. Because she refused to give approval to new vaccine recommendations without ever seeing them or their evidence and firing scientists without cause, she was fired. In my view, she’s a hero for standing up for science and speaking truth to power.In her first live interview since leaving the CDC, we review her background. That includes growing up in rural Wisconsin and getting her college and PhD education at UW-Madison, the latter in microbiology and immunology. She then went on to 18 years of government service with an extensive portfolio of jobs and management at BARDA, the White House, ARPA-H, and others, before becoming Acting Director of the CDC in early 2025.We discussed the horrific CDC shooting on August 8th, days after she started. Then we reviewed a conversation that we had on August 19th in which she laid out her exciting vision for the future of CDC, emphasizing the goal of prevention (BTW, CDC stands for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and asked me to help as an advisor. At the time, she was well aware, with growing tension, that her tenure at CDC might be limited. I asked about her perspective for the jobs of 4,300 people at CDC who have been terminated, which account for more than 1/3rd of the workforce, no less the gutting of the budget.Then we got into what she learned from this ordeal and her plans for the future, which includes a very ambitious initiative: 90/90/2035. As you’ll see from our conversation, Dr. Monarez is exceptionally resilient and an optimist. She’s got lots to do in the years ahead to carry out her mission of promoting human health!Dr. Monarez just started a Substack The Road Best Traveled so you can follow her there. It was a real privilege for me to do this interview with her. In deep admiration of her willingness to not only take on the job of CDC Director in tough circumstances, her professionalism during testimony at the Senate committee hearing, her impressive yet unrealized vision for transforming the CDC, and refusing to cave to immense pressure from the HHS Secretary to move ahead with his agenda. Thank you Julie, Stephen B. Thomas, PhD, David Dansereau, MSPT, Dr. Sara Wolfson, Vau Geha, and >500 others for tuning into my live video with The Road Best Traveled! Thanks for being a Ground Truths subscriber! Please spread the word. Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

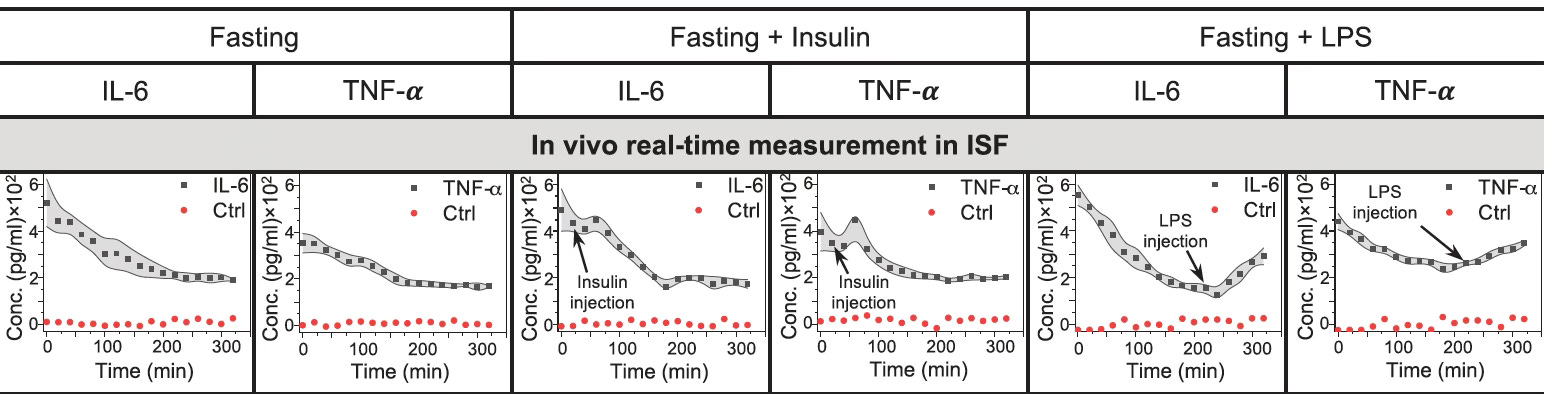

Prof Shana Kelley is the Neena Schwartz Professor of Chemistry and Biomedical Engineering at Northwestern University and President of the CZI Chicago Biohub, which brings together life scientists at Northwestern, University of Chicago, and U. Illinois Urbana Champaign. Her lab’s website provides recent publications in the 3 major areas of biomolecular sensors, rare and single cell analysis, and intracellular molecular delivery.You are undoubtedly familiar with wearable biosensors on the wrist and rings, and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), all of which can transmit physiologic data in real time to your smartphone. What is different about Prof Kelley’s work is the ingenious way of continuously tracking any proteins in our blood via a sensor that could function just like CGM in the future (hair thin sensor applied just below the skin and data relayed to your smartphone). A proof-of-concept paper in Science showed how exquisitely sensitive such a sensor worked to track inflammation markers [interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)] in the diabetic rat model. As seen. below, just the injection of insulin evoked inflammation, and introduction of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) did so markedly.This capability opens up the potential for monitoring body-wide inflammation in real time, but also extends to many other conditions such as autoimmune diseases, heart failure (e.g. continuous brain natriuetic peptide monitoring), and neurodegenerative diseases (with specific markers of neuroinflammation). This innovation represents a new dimension in individualized (precision) medicine.In our conversation, Shana takes us through the discovery of these unique bimolecular sensors that have no reagents, and use electricity to shake off the protein from DNA strands. And she maps out the path to clinical trials and commercialization in the next couple of years.Thank you Stephen B. Thomas, PhD, Linda Kemp, Lynn L, Pat Mumby PhD, David Hobson, and many others for tuning into my live video with Shana Kelley! Join me for my next live video in the app, along with posts on biomedical news and analysis.***********************************************************************Thanks you for your listening, reading and subscribing to Ground Truths.If you found this interesting PLEASE share it!That makes the work involved in putting these together especially worthwhile.All content on Ground Truths—its newsletters, analyses, and podcasts, are free, open-access.Paid subscriptions are voluntary and all proceeds from them go to support Scripps Research. They do allow for posting comments and questions, which I do my best to respond to. Please don't hesitate to post comments and give me feedback. Let me know topics that you would like to see covered.Many thanks to those who have contributed—they have greatly helped fund our summer internship programs for the past two years. It enabled us to accept and support 47 summer interns in 2025! Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

Thank you Bruce Lanphear, Clyde Wilson, Tracy Dennis-Tiwary, Diego Pereyra, Dr Mike Hunter, and many others for tuning into my live video with Charlotte Blease! Join me for my next live video in the app.Whether A.I. will transform the practice of medicine in a positive way remains controversial. Health researcher Prof Charlotte Blease, on faculty at Uppsala University in Sweden and researcher at Harvard University, has written a new book —Dr. Bot—that critically assesses the unmet needs in healthcare and whether A.I. can fulfill them. She provides an optimistic viewpoint (see the subtitle), and our conversation probes whether that is justified. She has a substack, too, hereThanks for listening to Ground Truths. Through analytic essays and podcasts, I try to cover the important issues and discoveries in life science and medicine. If you have suggestions for topics I should get into, please pass them along. Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

Thank you Sara Garcia, Andrew O'Malley BSc PhD, Sam Hester, Julie, Stephen B. Thomas, PhD, and so many others for tuning into my live video with Peter Hotez! Join me for my next live video in the app.Peter Hotez and I discuss his new book, co-authored with Michael Mann, SCIENCE UNDER SEIGE, on the anti-science superstorm culminating from the climate crisis, the Covid pandemic, and a vast interconnected network that has waged a direct assault on scientific truth.During our conversation we trace history of priors in civilization, such as Lysenko and Stalinism in the last century. And acknowledge the future role of A.I. for promoting infinite disinformation. Beyond human suffering and direct health outcome consequences (such as Red Covid), the toll this is taking on the career of young scientists, universities, public health agencies, and loss of public trust are reviewed. The interdependent role of the media and the wellness industry is touched on.The book and our conversation puts forth a call to arms, potential solutions, including the need to move away from invisible scientists and political activism.Thanks for listening to Ground Truths podcasts and reading the analytic posts.In case you missed any, these are a few recent and related ones:Podcasts with Michael Osterholm and Sanjay Gupta on their new books—The Big One and It Doesn’t Have to Hurt, respectively.Next up is Charlotte Blease and her new book Dr. Bot on where we are headed with medical A.I.If you found this interesting PLEASE share it!That makes the work involved in putting these together especially worthwhile.All content on Ground Truths—its newsletters, analyses, and podcasts, are free, open-access.Paid subscriptions are voluntary and all proceeds from them go to support Scripps Research. They do allow for posting comments and questions, which I do my best to respond to. Please don't hesitate to post comments and give me feedback. Let me know topics that you would like to see covered.Many thanks to those who have contributed—they have greatly helped fund our summer internship programs for the past two years. Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

Thank you Jose Bolanos MD, Dr. Zeest Khan, Lawrence Toole, Julie, Stephen B. Thomas, PhD, and many others for tuning into my live video with Dr. Sanjay Gupta. Join me for my next live video in the app.A Brief Summary of Our ConservationWe discussed the new understanding and approach to chronic pain, which affects nearly 1 in 4 adults. Dr. Gupta gets personal telling the story of his wife, Rebecca, who has an autoimmune disease and at one point he had to carry her up stairs. He also tells the story of his mother who had a back injury and didn’t want to live because of the pain. How his family members got relief is illuminating.Our whole understanding and approach to pain has changed, with the acronym change from RICE to MEAT.A newly approved drug Suzetrigine (Journavx) exploits the sodium channel gene mutation initially discovered via a family of fire walkers. It’s the first new pain medicine approved for more than 2 decades. Many other new non-opioid treatments are reviewed, no less lifestyle changes (anti-inflammatory diet and sleep), and acupuncture.Sanjay’s research over the past few years has led to a video special on CNN with the same title as the book, set to air 9 PM EST Sunday. If you know someone suffering chronic pain, please share the post. Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

This is a hybrid heart disease risk factor post of a podcast with Prof Bruce Lanphear on lead and a piece I was asked to write for the Washington Post on risk factors for heart disease.First, the podcast. You may have thought the problem with lead exposure was circumscribed to children, but it’s a much bigger issue than that. I’ll concentrate on the exposure risk to adults in this interview, including the lead-estrogen hypothesis. Bruce has been working on the subject of lead exposure for more than 30 years. Let me emphasize that the problem is not going away, as highlighted in a recent New England Journal of Medicine piece on lead contamination in Milwaukee schools, “The Latest Episode in an Ongoing Toxic Pandemic.”Transcript with links to the audio and citationsEric Topol (00:05):Well, hello. This is Eric Topol with Ground Truths, and I'm very delighted to welcome Professor Bruce Lanphear from Simon Fraser University in British Columbia for a very interesting topic, and that's about lead exposure. We tend to think about lead poisoning with the Flint, Michigan, but there's a lot more to this story. So welcome, Bruce.Bruce Lanphear (00:32):Thank you, Eric. It's great to be here.Eric Topol (00:33):Yeah. So you had a New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) Review in October last year, which was probably a wake up to me, and I'm sure to many others. We'll link to that, where you reviewed the whole topic, the title is called Lead Poisoning. But of course it's not just about a big dose, but rather chronic exposure. So maybe you could give us a bit of an overview of that review that you wrote for NEJM.Bruce Lanphear (01:05):Yeah, so we really focused on the things where we feel like there's a definitive link. Things like lead and diminished IQ in children, lead and coronary heart disease, lead and chronic renal disease. As you mentioned, we've typically thought of lead as sort of the overt lead poisoning where somebody becomes acutely ill. But over the past century what we've learned is that lead is one of those toxic chemicals where it's the chronic wear and tear on our bodies that catches up and it's at the root of many of these chronic diseases that are causing problems today.Eric Topol (01:43):Yeah, it's pretty striking. The one that grabbed me and kind of almost fell out of my chair was that in 2019 when I guess the most recent data there is 5.5 million cardiovascular deaths ascribed to relatively low levels, or I guess there is no safe level of lead exposure, that's really striking. That's a lot of people dying from something that cardiology and medical community is not really aware of. And there's a figure 3 [BELOW] that we will also show in the transcript, where you show the level where you start to see a takeoff. It starts very low and by 50 μg/liter, you're seeing a twofold risk and there's no threshold, it keeps going up. How many of us do you think are exposed to that type of level as adults, Bruce?Bruce Lanphear (02:39):Well, as adults, if we go back in time, all of us. If you go back to the 1970s when lead was still in gasoline, the median blood lead level of Americans was about 13 to 15 µg/dL. So we've all been exposed historically to those levels, and part of the reason we've begun to see a striking decline in coronary heart disease, which peaked in 1968. And by 1978, there was a 20% decline, 190,000 more people were alive than expected. So even in that first decade, there was this striking decline in coronary heart disease. And so, in addition to the prospective studies that have found this link between an increase in lead exposure and death from cardiovascular disease and more specifically coronary heart disease. We can look back in time and see how the decline in leaded gasoline led to a decline in heart disease and hypertension.Eric Topol (03:41):Yeah, but it looks like it's still a problem. And you have a phenomenal graph that's encouraging, where you see this 95% reduction in the lead exposure from the 1970s. And as you said, the factors that can be ascribed to like getting rid of lead from gasoline and others. But what is troubling is that we still have a lot of people that this could be a problem. Now, one of the things that was fascinating is that you get into that herbal supplements could be a risk factor. That we don't do screening, of course, should we do screening? And there's certain people that particularly that you consider at high risk that should get screened. So I wasn't aware, I mean the one type of supplements that you zoomed in on, how do you say it? Ayurvedic?Supplements With LeadBruce Lanphear (04:39):Oh yeah. So this is Ayurvedic medicine and in fact, I just was on a Zoom call three weeks ago with a husband and wife who live in India. The young woman had taken Ayurvedic medicine and because of that, her blood lead levels increased to 70 µg/dL, and several months later she was pregnant, and she was trying to figure out what to do with this. Ayurvedic medicine is not well regulated. And so, that's one of the most important sources when we think about India, for example. And I think you pointed out a really important thing is number one, we don't know that there's any safe level even though blood lead levels in the United States and Europe, for example, have come down by over 95%. The levels that we're exposed to and especially the levels in our bones are 10 to 100 times higher than our pre-industrial ancestors.Bruce Lanphear (05:36):So we haven't yet reached those levels that our ancestors were exposed to. Are there effects at even lower and lower levels? Everything would suggest, we should assume that there is, but we don't know down below, let's say one microgram per deciliter or that's the equivalent of 10 parts per billion of lead and blood. What we also know though is when leaded gasoline was restricted in the United States and Canada and elsewhere, the companies turned to the industrializing countries and started to market it there. And so, we saw first the epidemic of coronary heart disease in the United States, Canada, Europe. Then that's come down over the past 50 years. At the same time, it was rising in low to middle income countries. So today over 95% of the burden of disease from lead including heart disease is found in industrializing countries.Eric Topol (06:34):Right. Now, it's pretty striking, of course. Is it true that airlines fuel is still with lead today?Bruce Lanphear (06:45):Well, not commercial airlines. It's going to be a small single piston aircraft. So for example, when we did a study down around the Santa Clara County Airport, Reid-Hillview, and we can see that the children who live within a half mile of the airport had blood lead levels about 10% higher than children that live further away. And the children who live downwind, 25% higher still. Now, nobody's mapped out the health effects, but one of the things that's particularly troubling about emissions from small aircraft is that the particle size of lead is extraordinarily small, and we know how nanoparticles because they have larger surface area can be more problematic. They also can probably go straight up into the brain or across the pulmonary tissues, and so those small particles we should be particularly worried about. But it's been such a long journey to try to figure out how to get that out of aircraft. It's a problem. The EPA recognized it. They said it's an endangerment, but the industry is still pushing back.Eric Topol (07:55):Yeah, I mean, it's interesting that we still have these problems, and I am going to in a minute ask you what we can do to just eradicate lead as much as possible, but we're not there yet. But one study that seemed to be hard to believe that you cited in the review. A year after a ban leaded fuel in NASCAR races, mortality from coronary heart disease declined significantly in communities near racetracks. Can you talk about that one because it's a little bit like the one you just mentioned with the airports?Bruce Lanphear (08:30):Yeah. Now that study particularly, this was by Alex Hollingsworth, was particularly looking at people over 65. And we're working on a follow-up study that will look at people below 65, but it was quite striking. When NASCAR took lead out of their fuel, he compared the rates of coronary heart disease of people that live nearby compared to a control group populations that live further away. And he did see a pretty striking reduction. One of the things we also want to look at in our follow-up is how quickly does that risk begin to taper off? That's going to be really important in terms of trying to develop a strategy around preventing lead poisoning. How quickly do we expect to see it fall? I think it's probably going to be within 12 to 24 months that we'll see benefits.Eric Topol (09:20):That's interesting because as you show in a really nice graphic in adults, which are the people who would be listening to this podcast. Of course, they ought to be concerned too about children and all and reproductive health. But the point about the skeleton, 95% of the lead is there and the main organs, which we haven't mentioned the kidney and the kidney injury that occurs no less the cardiovascular, the blood pressure elevation. So these are really, and you mentioned not necessarily highlighted in that graphic, but potential cognitive hit as well. You also wrote about how people who have symptoms of abdominal pain, memory impairment, and high blood pressure that's unexplained, maybe they should get a blood level screening. I assume those are easy to get, right?Bruce Lanphear (10:17):Oh yeah, absolutely. You can get those in any hospital, any clinic across the country. We're still struggling with having those available where it's most needed in the industrializing countries, but certainly available here. Now, we don't expect that for most people who have those symptoms, lead poisoning is going to be the cause, right. It'd still be unusual unless you work in

Eric Topol (00:06):Hello, this is Eric Topol from Ground Truths, and I'm delighted to welcome Owen Tripp, who is a CEO of Included Health. And Owen, I'd like to start off if you would, with the story from 2016, because really what I'm interested in is patients and how to get the right doctor. So can you tell us about when you lost your hearing in your right ear back, what, nine years ago or so?Owen Tripp (00:38):Yeah, it's amazing to say nine years, Eric, but obviously as your listeners will soon understand a pretty vivid memory in my past. So I had been working as I do and noticed a loss of hearing in my right ear. I had never experienced any hearing loss before, and I went twice actually to a sort of national primary care chain that now owned by Amazon actually. And they described it as eustachian tube dysfunction, which is a pretty benign common thing that basically meant that my tubes were blocked and that I needed to have some drainage. They recommended Sudafed to no effect. And it was only a couple weeks later where I was walking some of the senior medical team at my company down to the San Francisco Giants game. And I was describing this experience of hearing loss and I said I was also losing a little bit of sensation in the right side of my face. And they said, that is not eustachian tube dysfunction. And well, I can let the story unfold from there. But basically my colleagues helped me quickly put together a plan to get this properly diagnosed and treated. The underlying condition is called vestibular schwannoma, even more commonly known as an acoustic neuroma. So a pretty rare benign brain tumor that exists on the vestibular nerve, and it would've cost my life had it not been treated.Eric Topol (02:28):So from what I gather, you saw an ENT physician, but that ENT physician was not really well versed in this condition, which is I guess a bit surprising. And then eventually you got to the right ENT physician in San Francisco. Is that right?Owen Tripp (02:49):Well, the first doctor was probably an internal medicine doctor, and I think it's fair to say that he had probably not seen many, if any cases. By the time I reached an ENT, they were interested in working me up for what's known as sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL), which is basically a fancy term for you lose hearing for a variety of possible pathologies and reasons, but you go through a process of differential diagnosis to understand what's actually going on. By the time that I reached that ENT, the audio tests had showed that I had significant hearing loss in my right ear. And what an MRI would confirm was this mass that I just described to you, which was quite large. It was already about a centimeter large and growing into the inner ear canal.Eric Topol (03:49):Yeah, so I read that your Stanford brain scan suggested it was about size of a plum and that you then got the call that you had this mass in your brainstem tumor. So obviously that's a delicate operation to undergo. So the first thing was getting a diagnosis and then the next thing was getting the right surgeon to work on your brain to resect this. So how did you figure out who was the right person? Because there's only a few thousand of these operations done every year, as I understand.Owen Tripp (04:27):That's exactly right. Yeah, very few. And without putting your listeners to sleep too early in our discussion, what I'll say is that there are a lot of ways that you can actually do this. There are very few cases, any approach really requires either shrinking or removing that tumor entirely. My size of tumor meant it was really only going to be a surgical approach, and there I had to decide amongst multiple potential approaches. And this is what's interesting, Eric, you started saying you wanted to talk about the patient experience. You have to understand that I'm somebody, while not a doctor, I lead a very large healthcare company. We provide millions of visits and services per year on very complex medical diagnoses down to more standard day-to-day fare. And so, being in the world of medical complexity was not daunting on the basics, but then I'm the patient and now I have to make a surgical treatment decision amongst many possible choices, and I was able to get multiple opinions.Owen Tripp (05:42):I got an opinion from the House clinic, which is closer to you in LA. This is really the place where they invented the surgical approach to treating these things. I also got an approach shared with me from the Mayo Clinic and one from UCSF and one from Stanford, and ultimately, I picked the Stanford team. And these are fascinating and delicate structures as you know that you're dealing with in the brain, but the surgery is a long surgery performed by multiple surgeons. It's such an exhausting surgery that as you're sort of peeling away that tumor that you need relief. And so, after a 13 hour surgery, multiple nights in the hospital and some significant training to learn how to walk and move and not lose my balance, I am as you see me today, but it was possible under one of the surgical approaches that I would've lost the use of the right side of my face, which obviously was not an option given what I given what I do.Eric Topol (06:51):Yeah, well, I know there had to be a tough rehab and so glad that you recovered well, and I guess you still don't have hearing in that one ear, right?Owen Tripp:That's right.Eric Topol:But otherwise, you're walking well, and you've completely recovered from what could have been a very disastrous type of, not just the tumor itself, but also the way it would be operated on. 13 hours is a long time to be in the operating room as a patient.Owen Tripp (07:22):You've got a whole team in there. You've got people testing nerve function, you've got people obviously managing the anesthesiology, which is sufficiently complex given what's involved. You've got a specialized ENT called a neurotologist. You've got the neurosurgeon who creates access. So it's quite a team that does these things.Eric Topol (07:40):Yeah, wow. Now, the reason I wanted to delve into this from your past is because I get a call or email or whatever contact every week at least one, is can you help me find the right doctor for such and such? And this has been going on throughout my career. I mean, when I was back in 20 years ago at Cleveland Clinic, the people on the board, I said, well, I wrote about it in one of my books. Why did you become a trustee on the board? And he said, so I could get access to the right doctor. And so, this is amazing. We live in an information era supposedly where people can get information about this being the most precious part, which is they want to get the right diagnosis, they want to get the right treatment or prevention, whatever, and they can't get it. And I'm finding this just extraordinary given that we can do deep research through several different AI models and get reports generated on whatever you want, but you can't get the right doctor. So now let's go over to what you're working on. This company Included Health. When did you start that?Owen Tripp (08:59):Well, I started the company that was known as Grand Rounds in 2011. And Grand Rounds still to this day, we've rebranded as Included Health had a very simple but powerful idea, one you just obliquely referred to, which is if we get people to higher quality medicine by helping them find the right level and quality of care, that two good things would happen. One, the sort of obvious one, patients would get better, they'd move on with their lives, they'd return to health. But two and critically that we would actually help the system overall with the cost burden of unnecessary, inappropriate and low quality care because the coda to the example you gave of people calling you looking for a physician referral, and you and I both know this, my guess is you've probably had to clean plenty of it up in your career is if you go to the wrong doctor, you don't get out of the problem. The problem just persists. And that patient is likely to bounce around like a ping pong ball until they find what they actually need. And that costs the payers of healthcare in this country a lot of money. So I started the company in 2011 to try to solve that problem.Eric Topol (10:14):Yeah, one example, a patient of mine who I've looked after for some 35 years contacted me and said, a very close friend of mine lives in the Palm Springs region and he has this horrible skin condition and he's tortured and he's been to six centers, UCSF, Stanford, Oregon Health Science, Eisenhower, UCLA, and he had a full workup and he can't sleep because he's itching all the time. His whole skin is exfoliating and cellulitis and he had biopsies everywhere. He’s put on all kinds of drugs, monoclonal antibodies. And I said to this patient of mine I said, I don't know, this is way out of my area. I checked at Scripps and turns out there was this kind of the Columbo of dermatology, he can solve any mystery. And the patient went to see him, and he was diagnosed within about a minute that he had scabies, and he was treated and completely recovered after having thousands and thousands of dollars of all these workups at these leading medical centers that you would expect could make a diagnosis of scabies.Owen Tripp (11:38):That’s a pretty common diagnosis.Eric Topol (11:40):Yeah. I mean you might expect it more in somebody who was homeless perhaps, but that doesn't mean it can't happen in anyone. And within the first few minutes he did a scrape and showed the patient under the microscope and made a definitive diagnosis and the patient to this day is still trying to pay all his bills for all these biopsies and drugs and whatnot, and very upset that he went through all this for over a year and he thought he wanted to die, it was so bad. Now, I had never heard of Included Health and you have now links with a third of the Fortune 100 companies. So what do you do wi

Eric Topol (00:05):Hello, it's Eric Topol from Ground Truths, and I've got some really exciting stuff to talk to you about today. And it's about the announcement for a new Center for pediatric CRISPR Cures. And I'm delight to introduce doctors Jennifer Doudna and Priscilla Chan. And so, first let me say this is amazing to see this thing going forward. It's an outgrowth of a New England Journal paper and monumental report on CRISPR in May. [See the below post for more context]Let me introduce first, Dr. Doudna. Jennifer is the Li Ka Shing Chancellor's Chair and a Professor in the departments of chemistry and of molecular and cell biology at the University of California Berkeley. She's also the subject of this book, one of my favorite books of all time, the Code Breaker. And as you know, the 2020 Nobel Prize laureate for her work in CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, and she founded the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) back 10 years ago. So Jennifer, welcome.Jennifer Doudna (01:08):Thank you, Eric. Great to be here.Eric Topol (01:10):And now Dr. Priscilla Chan, who is the co-founder of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) that also was started back in 2015. So here we are, a decade later, these two leaders. She is a pediatrician having trained at UCSF and is committed to the initiative which has as its mission statement, “to make it possible to cure, prevent, and manage all diseases in this century.” So today we're going to talk about a step closer to that. Welcome, Priscilla.Priscilla Chan (01:44):Thank you. Thanks for having me.Eric Topol (01:46):Alright, so I thought we'd start off by, how did you two get together? Have you known each other for over this past decade since you both got all your things going?Jennifer Doudna (01:56):Yes, we have. We've known each other for a while. And of course, I've admired the progress at the CZI on fundamental science. I was an advisor very early on and I think actually that's how we got to know each other. Right, Priscilla?Priscilla Chan (02:11):Yeah, that's right. We got to know each other then. And we've been crisscrossing paths. And I personally remember the day you won the Nobel Prize. It was in the heart of the pandemic and a lot of celebrations were happening over Zoom. And I grabbed my then 5-year-old and got onto the UCSF celebration and I was like, look, this is happening. And it was really cool for me and for my daughter.Eric Topol (02:46):Well, it's pretty remarkable convergence leading up to today's announcement, but I know Priscilla, that you've been active in this rare disease space, you've had at CZI a Rare As One Project. Maybe you could tell us a bit about that.Priscilla Chan (03:01):Yeah, so at CZI, we work on basic science research, and I think that often surprises people because they know that I'm a pediatrician. And so, they often think, oh, you must work in healthcare or healthcare delivery. And we've actually chosen very intentionally to work in basic science research. In part because my training as a pediatrician at UCSF. As you both know, UCSF is a tertiary coronary care center where we see very unusual and rare cases of pediatric presentations. And it was there where I learned how little we knew about rare diseases and diseases in general and how powerful patients were. And that research was the pipeline for hope and for new discoveries for these families that often otherwise don't have very much access to treatments or cures. They have a PDF that maybe describes what their child has. And so, I decided to invest in basic science through CZI, but always saw the power of bringing rare disease patient cohorts. One, because if you've ever met a parent of a child with rare disease, they are a force to be reckoned with. Two, they can make research so much better due to their insights as patients and patient advocates. And I think they close the distance between basic science and impact in patients. And so, we've been working on that since 2019 and has been a passion of ours.Eric Topol (04:40):Wow, that's great. Now Jennifer, this IGI that you founded a decade ago, it's doing all kinds of things that are even well beyond rare diseases. We recently spoke, I know on Ground Truths about things as diverse as editing the gut microbiome in asthma and potentially someday Alzheimer’s. But here you were very much involved at IGI with the baby KJ Muldoon. Maybe you could take us through this because this is such an extraordinary advance in the whole CRISPR Cures story.Jennifer Doudna (05:18):Yes, Eric. It's a very exciting story and we're very, very proud of the teamwork that went into making it possible to cure baby KJ of his very rare disease. And in brief, the story began back in August of last year when he was born with a metabolic disorder that prevented him from digesting protein, it's called a urea cycle disorder and rare, but extremely severe. And to the point where he was in the ICU and facing a very, very difficult prognosis. And so, fortunately his clinical team at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) reached out to Fyodor Urnov, who is the Director of Translational Medicine at the IGI here in the Bay Area. They teamed up and realized that they could quickly diagnose that child because we had an IRB approved here at the IGI that allowed us to collect patient samples and do diagnosis. So that was done.Jennifer Doudna (06:26):We created an off-the-shelf CRISPR therapy that would be targeted to the exact mutation that caused that young boy's disease. And then we worked with the FDA in Washington to make sure that we could very safely proceed with testing of that therapy initially in the lab and then ultimately in two different animal models. And then we opened a clinical trial that allowed that boy to be enrolled with, of course his parents' approval and for him to be dosed and the result was spectacular. And in fact, he was released from the hospital recently as a happy, healthy child, gaining lots of weight and looking very chunky. So it's really exciting.Eric Topol (07:16):It's so amazing. I don't think people necessarily grasp this. This timeline [see above] that we'll post with this is just mind boggling how you could, as you said Jennifer, in about six months to go from the birth and sequencing through cell specific cultures with the genome mutations through multiple experimental models with non-human primates even, looking at off-target effects, through the multiple FDA reviews and then dosing, cumulatively three dosing to save this baby's life. It really just amazing. Now that is a template. And before we go to this new Center, I just wanted to also mention not just the timeline of compression, which is unimaginable and the partnership that you've had at IGI with I guess Danaher to help manufacture, which is just another part of the story. But also the fact that you're not just even with CRISPR 1.0 as being used in approvals previously for sickle cell and β-thalassemia, but now we're talking about base editing in vivo in the body using mRNA delivery. So maybe you could comment on that, Jennifer.Jennifer Doudna (08:38):Yeah, very good point. So yeah, we used a version of CRISPR that was created by David Liu at the Broad Institute and published and available. And so, it was possible to create that, again, targeted to the exact mutation that caused baby KJ’s disease. And fortunately, there was also an off-the-shelf way to deliver it because we had access to lipid nanoparticles that were developed for other purposes including vaccinations. And the type of disease that KJ suffered from is one that is treatable by editing cells in the liver, which is where the lipid nanoparticle naturally goes. So there were definitely some serendipity here, but it was amazing how all of these pieces were available. We just had to pull them together to create this therapy.Eric Topol (09:30):Yeah, no, it is amazing. So that I think is a great substrate for starting a new Center. And so, maybe back to you Priscilla, as to what your vision was when working with Jennifer and IGI to go through with this.Priscilla Chan (09:45):I think the thing that's incredibly exciting, you mentioned that at CZI our mission is to cure, prevent, and manage all disease. And when we talked about this 10 years ago, it felt like this far off idea, but every day it seems closer and closer. And I think the part that's super exciting about this is the direct connection between the basic science that's happening in CRISPR and the molecular and down to the nucleotide understanding of these mutations and the ability to correct them. And I think many of us, our imaginations have included this possibility, but it's very exciting that it has happened with baby KJ and CHOP. And we need to be able to do the work to understand how we can treat more patients this way, how to understand the obstacles, unblock them, streamline the process, bring down the cost, so that we better understand this pathway for treatment, as well as to increasingly democratize access to this type of platform. And so, our hope is to be able to do that. Take the work and inspiration that IGI and the team at CHOP have done and continue to push forward and to look at more cases, look at more organ systems. We're going to be looking in addition to the liver, at the bone marrow and the immune system.Priscilla Chan (11:17):And to be able to really work through more of the steps so that we can bring this to more families and patients.Eric Topol (11:30):Yeah, well it's pretty remarkable because here you have incurable ultra-rare diseases. If you can help these babies, just think of what this could do in a much broader context. I mean there a lot of common diseases have their roots with some of these very rare ones. So how do you see going forward, Jennifer, as to where you UC Berkeley, Gladstone, UCSF. I'm envious of you all up there in Northern California I have to say, will pull this off. How will you get the first similar case to KJ Muld

“To navigate proof, we must reach into a thicket of errors and biases. We must confront monsters and embrace uncertainty, balancing — and rebalancing —our beliefs. We must seek out every useful fragment of data, gather every relevant tool, searching wider and climbing further. Finding the good foundations among the bad. Dodging dogma and falsehoods. Questioning. Measuring. Triangulating. Convincing. Then perhaps, just perhaps, we'll reach the truth in time.”—Adam KucharskiMy conversation with Professor Kucharski on what constitutes certainty and proof in science (and other domains), with emphasis on many of the learnings from Covid. Given the politicization of science and A.I.’s deepfakes and power for blurring of truth, it’s hard to think of a topic more important right now.Audio file (Ground Truths can also be downloaded on Apple Podcasts and Spotify)Eric Topol (00:06):Hello, it's Eric Topol from Ground Truths and I am really delighted to welcome Adam Kucharski, who is the author of a new book, Proof: The Art and Science of Certainty. He’s a distinguished mathematician, by the way, the first mathematician we've had on Ground Truths and a person who I had the real privilege of getting to know a bit through the Covid pandemic. So welcome, Adam.Adam Kucharski (00:28):Thanks for having me.Eric Topol (00:30):Yeah, I mean, I think just to let everybody know, you're a Professor at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and also noteworthy you won the Adams Prize, which is one of the most impressive recognitions in the field of mathematics. This is the book, it's a winner, Proof and there's so much to talk about. So Adam, maybe what I'd start off is the quote in the book that captivates in the beginning, “life is full of situations that can reveal remarkably large gaps in our understanding of what is true and why it's true. This is a book about those gaps.” So what was the motivation when you undertook this very big endeavor?Adam Kucharski (01:17):I think a lot of it comes to the work I do at my day job where we have to deal with a lot of evidence under pressure, particularly if you work in outbreaks or emerging health concerns. And often it really pushes the limits, our methodology and how we converge on what's true subject to potential revision in the future. I think particularly having a background in math’s, I think you kind of grow up with this idea that you can get to these concrete, almost immovable truths and then even just looking through the history, realizing that often isn't the case, that there's these kind of very human dynamics that play out around them. And it's something I think that everyone in science can reflect on that sometimes what convinces us doesn't convince other people, and particularly when you have that kind of urgency of time pressure, working out how to navigate that.Eric Topol (02:05):Yeah. Well, I mean I think these times of course have really gotten us to appreciate, particularly during Covid, the importance of understanding uncertainty. And I think one of the ways that we can dispel what people assume they know is the famous Monty Hall, which you get into a bit in the book. So I think everybody here is familiar with that show, Let's Make a Deal and maybe you can just take us through what happens with one of the doors are unveiled and how that changes the mathematics.Adam Kucharski (02:50):Yeah, sure. So I think it is a problem that's been around for a while and it's based on this game show. So you've got three doors that are closed. Behind two of the doors there is a goat and behind one of the doors is a luxury car. So obviously, you want to win the car. The host asks you to pick a door, so you point to one, maybe door number two, then the host who knows what's behind the doors opens another door to reveal a goat and then ask you, do you want to change your mind? Do you want to switch doors? And a lot of the, I think intuition people have, and certainly when I first came across this problem many years ago is well, you've got two doors left, right? You've picked one, there's another one, it's 50-50. And even some quite well-respected mathematicians.Adam Kucharski (03:27):People like Paul Erdős who was really published more papers than almost anyone else, that was their initial gut reaction. But if you work through all of the combinations, if you pick this door and then the host does this, and you switch or not switch and work through all of those options. You actually double your chances if you switch versus sticking with the door. So something that's counterintuitive, but I think one of the things that really struck me and even over the years trying to explain it is convincing myself of the answer, which was when I first came across it as a teenager, I did quite quickly is very different to convincing someone else. And even actually Paul Erdős, one of his colleagues showed him what I call proof by exhaustion. So go through every combination and that didn't really convince him. So then he started to simulate and said, well, let's do a computer simulation of the game a hundred thousand times. And again, switching was this optimal strategy, but Erdős wasn't really convinced because I accept that this is the case, but I'm not really satisfied with it. And I think that encapsulates for a lot of people, their experience of proof and evidence. It's a fact and you have to take it as given, but there's actually quite a big bridge often to really understanding why it's true and feeling convinced by it.Eric Topol (04:41):Yeah, I think it's a fabulous example because I think everyone would naturally assume it's 50-50 and it isn't. And I think that gets us to the topic at hand. What I love, there's many things I love about this book. One is that you don't just get into science and medicine, but you cut across all the domains, law, mathematics, AI. So it's a very comprehensive sweep of everything about proof and truth, and it couldn't come at a better time as we'll get into. Maybe just starting off with math, the term I love mathematical monsters. Can you tell us a little bit more about that?Adam Kucharski (05:25):Yeah, this was a fascinating situation that emerged in the late 19th century where a lot of math’s, certainly in Europe had been derived from geometry because a lot of the ancient Greek influence on how we shaped things and then Newton and his work on rates of change and calculus, it was really the natural world that provided a lot of inspiration, these kind of tangible objects, tangible movements. And as mathematicians started to build out the theory around rates of change and how we tackle these kinds of situations, they sometimes took that intuition a bit too seriously. And there was some theorems that they said were intuitively obvious, some of these French mathematicians. And so, one for example is this idea of you how things change smoothly over time and how you do those calculations. But what happened was some mathematicians came along and showed that when you have things that can be infinitely small, that intuition didn't necessarily hold in the same way.Adam Kucharski (06:26):And they came up with these examples that broke a lot of these theorems and a lot of the establishments at the time called these things monsters. They called them these aberrations against common sense and this idea that if Newton had known about them, he never would've done all of his discovery because they're just nuisances and we just need to get rid of them. And there's this real tension at the core of mathematics in the late 1800s where some people just wanted to disregard this and say, look, it works for most of the time, that's good enough. And then others really weren't happy with this quite vague logic. They wanted to put it on much sturdier ground. And what was remarkable actually is if you trace this then into the 20th century, a lot of these monsters and these particularly in some cases functions which could almost move constantly, this constant motion rather than our intuitive concept of movement as something that's smooth, if you drop an apple, it accelerates at a very smooth rate, would become foundational in our understanding of things like probability, Einstein's work on atomic theory. A lot of these concepts where geometry breaks down would be really important in relativity. So actually, these things that we thought were monsters actually were all around us all the time, and science couldn't advance without them. So I think it's just this remarkable example of this tension within a field that supposedly concrete and the things that were going to be shunned actually turn out to be quite important.Eric Topol (07:53):It's great how you convey how nature isn't so neat and tidy and things like Brownian motion, understanding that, I mean, just so many things that I think fit into that general category. In the legal, we won't get into too much because that's not so much the audience of Ground Truths, but the classic things about innocent and until proven guilty and proof beyond reasonable doubt, I mean these are obviously really important parts of that overall sense of proof and truth. We're going to get into one thing I'm fascinated about related to that subsequently and then in science. So before we get into the different types of proof, obviously the pandemic is still fresh in our minds and we're an endemic with Covid now, and there are so many things we got wrong along the way of uncertainty and didn't convey that science isn't always evolving search for what is the truth. There's plenty no shortage of uncertainty at any moment. So can you recap some of the, you did so much work during the pandemic and obviously some of it's in the book. What were some of the major things that you took out of proof and truth from the pandemic?Adam Kucharski (09:14):I think it was almost this story of two hearts because on the one hand, science was the thing that got us where we are today. The reas

Thanks to so many of you who joined our live conversation with Devi Sridhar! Professor Devi Sridhar is the Chair of Global Public Health at the University of Edinburgh. Over the past 2 decades she has become one of the world’s leading authorities and advisors for promoting global health. Her new book —How No to Die Too Soon—provides a unique outlook for extending healthspan with a global perspective admixed with many personal stories. We talked about lifestyle factors with lessons from Japan (on diet) and the Netherlands (on physical activity), ultra-processed foods, air pollution and water quality, the prevention model in Finland, guns, inequities, the US situation for biomedical research and public health agency defunding, and much more. Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe

My conversation with Matthew Walker, PhD on faculty at UC Berkeley where he is a professor of neuroscience and psychology, the founder and director of the Center for Human Sleep Science, and has a long history of seminal contributions on sleep science and health. Audio File (also downloadable at Apple Podcast and Spotify)“Sleep is a non-negotiablebiological state required for the maintenance of human life . . . our needsfor sleep parallel those for air, food, and water.”—Grandner and FernandezEric Topol (00:07):Hello, it's Eric Topol with Ground Truths, and I am really delighted to welcome Matt Walker, who I believe has had more impact on sleep health than anyone I know. It's reflected by the fact that he is a Professor at UC Berkeley, heads up the center that he originated for Human Sleep Science. He wrote a remarkable book back in 2017, Why We Sleep, and also we'll link to that as well as the TED Talk of 2019. Sleep is Your Superpower with 24 million views. That's a lot of views here.Matt Walker:Striking, isn't it?Eric Topol:Wow. I think does reflect the kind of impact, you were onto the sleep story sooner, earlier than anyone I know. And what I wanted to do today was get to the updates because you taught us a lot back then and a lot of things have been happening in these years since. You're on it, of course, I think you have a podcast Sleep Diplomat, and you're obviously continued working on the science of sleep. But maybe the first thing I'd ask you about is in the last few years, what do you think has been, are there been any real changes or breakthroughs in the field?What Is New?Matt Walker (01:27):Yeah, I think there has been changes, and maybe we'll speak about one of them, which is the emergence of this brain cleansing system called the glymphatic system, but spreading that aside for potential future discussion. I would say that there are maybe at least two fascinating areas. The first is the broader impact of sleep on much more complex human social interactions. We think of sleep at maybe the level of the cell or systems or whole scale biology or even the entire organism. We forget that a lack of sleep, or at least the evidence suggests a lack of sleep will dislocate each other, one from the other. And there's been some great work by Dr. Eti Ben Simon for example, demonstrating that when you are sleep deprived, you become more asocial. So you basically become socially repellent. You want to withdraw, you become lonely. And what's also fascinating is that other people, even they don't know that you sleep deprived, they rate you as being less socially sort of attractive to engage with.Matt Walker (02:35):And after interacting with you, the sleep deprived individual, even though they don't know you're sleep deprived, they themselves walk away feeling more lonely themselves. So there is a social loneliness contagion that happens that a sleep deprived lonely individual can have almost a viral knock on effect that causes loneliness in another well-rested individual. And then that work spanned out and it started to demonstrate that another impact of a lack of sleep socially is that we stop wanting to help other people. And you think, well, helping behavior that's not really very impactful. Try to tell me of any major civilization that has not risen up through human cooperation and helping. There just isn't one. Human cooperative behavior is one of our innate traits as homo sapiens. And what they discovered is that when you are insufficiently slept, firstly, you don't wish to help other people. And you can see that at the individual level.Matt Walker (03:41):You can see it in groups. And then there was a great study again by Dr. Eti Ben Simon that demonstrated this at a national level because what she did was she looked at this wonderful manipulation of one hour of sleep that happens twice a year to 1.6 billion people. It's called daylight savings time at spring. Yeah, when you lose one hour of sleep opportunity. She looked at donations across the nation and sure enough, there was this big dent in donation giving in the sleepy Monday and Tuesday after the clock change. Because of that sleep, we become less willing to empathetically and selflessly help other individuals. And so, to me I think it's just a fascinating area. And then the other area I think is great, and I'm sorry I'm racing forward because I get so excited. But this work now looking at what we call genetic short sleepers and sort of idiots like me have been out there touting the importance of somewhere between seven to nine hours of sleep.Matt Walker (04:48):And once you get less than that, and we'll perhaps speak about that, you can see biological changes. But there is a subset of individuals who, and we've identified at least two different genes. One of them is what we call the DEC2 gene. And it seems to allow individuals to sleep about five hours, maybe even a little bit less and show no impairment whatsoever. Now we haven't tracked these individuals across the lifespan to truly understand does it lead to a higher mortality risk. But so far, they don't implode like you perhaps or I would do when you are limited to this anemic diet of five hours of sleep. They hang in there just fine. And I think philosophically what that tells me, and by the way, for people who are listening thinking, gosh, I think I'm probably one of those people. Statistically, I think you are more likely to be struck by lightning in your lifetime than you are to have the DEC2 gene. Think about what tells us, Eric. It tells us that there is a moment in biology in the evolution of this thing called the sleep physiological need that has changed such that mother nature has found a genetic way to ZIP file sleep.Matt Walker (06:14):You can essentially compress sleep from seven to nine hour need, down to five to six hour need. To me, that is absolutely fascinating. So now the race is on, what are the mechanisms that control this? How do we understand them? I'm sure much to my chagrin, society would like to then say, okay, is there a pill that I can take to basically ZIP file my own sleep and then it becomes an arms race in my mind, which is then all of a sudden six hours becomes the new eight hours and then everyone is saying, well, six hours is my need. Well I'll go to four hours and then it's this arms race of de-escalation of sleep. Anyway, I'm going on and on, does that help give you a sense of two of the what I feel the more fascinating areas?Eric Topol (07:01):Absolutely. When I saw the other recent report on the short sleep gene variant and thought about what the potential of that would be with respect to potential drug development or could you imagine genome editing early in life that you don't need any sleep? I mean crazy stuff.Matt Walker (07:19):It was amazing.Glymphatics and Deep Sleepfor more, see previous Ground Truths on this topic Eric Topol (07:22):No, the mechanism of course we have to work out and also what you mentioned regarding the social and the behavior engagement, all that sort of thing, it was just fascinating stuff. Now we touched on one thing early on to come back to the glymphatics these channels to get rid of the waste metabolites from the brain each night that might be considered toxic metabolites. We've learned a lot about those and of course there's some controversy about it. What are your thoughts?Matt Walker (07:55):Yeah, I think there's really quite comprehensive evidence suggesting that the brain has this cleansing system like the body has one the lymphatic system, the brain has one the glymphatic system named after these glial cells that make it up. And I think there's been evidence from multiple groups across multiple different species types, from mouse models all the way up to human models suggesting that there is a state dependent control of the brain cleansing system, which is a fancy way of saying if you are awake in light NREM, deep NREM or perhaps you're just quiet and you are resting in your wakefulness, the glymphatic system is not switched on at the same rate across all of those different brain states. And I think the overwhelming evidence so far using different techniques in different species from different groups is that sleep is a preferential time. It's not an exclusive time, it's a preferential time when that brain cleansing system kicks into gear because as some people have, I think argued, and you could say it's hyperbolic, but wakefulness is low level from a biochemicals perspective, it's low level brain damage and sleep is therefore your sanitary salvation that combat that biochemical cascade.Matt Walker (09:15):So in other words, a better way of putting it would be, sleep is the price that you pay for wakefulness in some ways. And I think there was a recent controversial study that came out in 2022 or 2023, and they actually suggested quite the opposite. They said using their specific imaging methods, they found that the sort of clearance, the amount of cerebral spinal fluid, which is what washes through the brain to cleanse the toxins, the rate of that flow of cerebral spinal fluid was highest during wakefulness and lowest during deep NREM sleep, the exact opposite of what others have found. Now, I think the defendants of the glymphatic sleep dependent hypothesis pushed back and said, well, if you look at the imaging methods. Firstly, they’re nonstandard. Secondly, they were measuring the cerebral spinal flow in an artificial way because they were actually perfusing solutions through the brain rather than naturally letting it flow and therefore the artificial forcing of fluid changed the prototypical result you would get.Matt Walker (10:27):And they also argued that the essentially kind of the sampling rate, so how quickly are you taking snapshots of the cerebral spinal fluid flow. Those were different and they were probably missing some of the sleep dependent slow oscillations that seemed to sort of drive that pulsatil

Thank you Richard DeWald, Michael Mann, Dr Avneesh Khare, Maud Pasturaud, Lower Dementia Risk, and many others for tuning into my live video with Katie Couric! Join me for my next live video in the app. Get full access to Ground Truths at erictopol.substack.com/subscribe