Discover Hack Music Theory

Hack Music Theory

Hack Music Theory

Author: Kate & Ray Harmony

Subscribed: 2,533Played: 30,021Subscribe

Share

© 2025 Revolution Harmony

Description

Welcome to the unorthodoX teachings of multi award-winning music lecturer Ray Harmony. Co-taught by Kate Harmony, his wife and protégé. Ray's world-renowned method of understanding music is known as Hack Music Theory, and their YouTube tutorials that teach his unique method have over 10 million views.

As a songwriter and producer, Ray has made music with Grammy winners and multiplatinum artists including Serj Tankian (System Of A Down) and Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine).

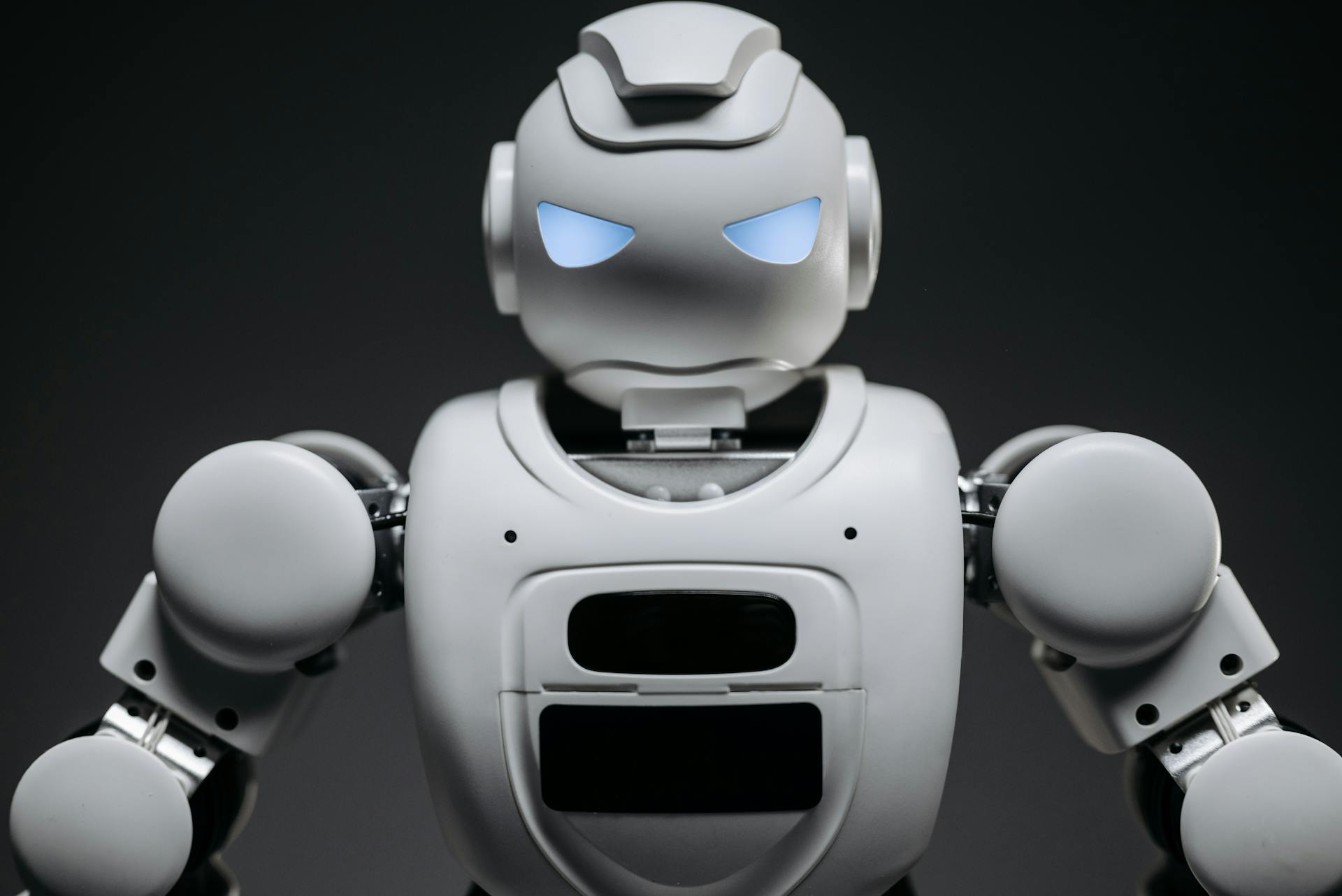

This space is like a songwriters' ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last. Join over 250,000 YouTube subscribers learning the fast, easy, and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain't no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs!

Start now by downloading Ray's free book @ https://HackMusicTheory.com

As a songwriter and producer, Ray has made music with Grammy winners and multiplatinum artists including Serj Tankian (System Of A Down) and Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine).

This space is like a songwriters' ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last. Join over 250,000 YouTube subscribers learning the fast, easy, and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain't no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs!

Start now by downloading Ray's free book @ https://HackMusicTheory.com

106 Episodes

Reverse

Don’t Trust Me,I’m an Expert.

Confessions of an INFJ. I’m a multi award-winning music lecturer with over 30 years of teaching experience, 10 of those years being at one of the UK’s largest colleges. I studied classical guitar, piano, and music theory (all to the highest grade) at the world-renowned Royal Schools of Music. Then I moved to Los Angeles to study contemporary guitar and vocals at the world-renowned Musicians Institute. On top of that, I’ve made music with Grammy winners and multiplatinum artists, including Serj Tankian (System Of A Down) and Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine). So with regards to making music and teaching music, it’s safe to say that I’m an expert. But if you want to learn how to make music, don’t trust me! Wait… What?! Let me explain. But first, we need to take a little detour. On average, people can be divided into 16 personality types. This is known as the Myers-Briggs (or MBTI) system, and it’s based on Carl Jung’s model of the eight cognitive functions. It’s an utterly brilliant system that will change your life, if you take the time to learn it. You can start by simply discovering what your personality type is. To do this, I recommend Dr. Dario Nardi’s free online test, which you can take at: keys2cognition.com. Invite your friends and family to do it, too. Then, if you want to learn about the 16 personality types, I recommend going to the source and reading the book “Gifts Differing” by Isabel Briggs Myers and Peter B. Myers. Okay, the detour’s over. So now, what’s personality type got to do with not trusting me? Everything! That’s the short answer. The slightly longer answer is this: Personality type has everything to do with everything! And that’s not hyperbole. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. If you’re like me, then you’re also constantly looking around wondering why we can’t all just get along by respecting each other’s differences and beliefs. In fact, one of the countless reasons I deleted all my social media accounts 10 years ago, was that I couldn’t take any more angry arguments. Just look at any social media thread, and you’ll see how obvious it is that those people are talking (or shouting) past each other. That’s because they have very different personality types, and therefore, very different perspectives. They’re never going to agree. They can’t. And arguing over which perspective is correct is in actual fact arguing over which personality type is correct. But that’s a meaningless pursuit, because no one personality type is better than any other. Each type has its unique gifts. And each type has its unique perspectives. The only discussion worth having is which perspective is best suited for each personality type. A healthy society needs all the personality types and their differing perspectives, otherwise it loses its balance and harmony. And then descends into intolerance. Now, here’s the life-changing conclusion you reach when you learn about personality types. Are you ready? You might want to sit down for this. Okay, here it is: Every perspective will always be wrong for 15 out of the 16 personality types. In other words, every perspective you have on every topic will be 94% wrong according to all the personality types. If there’s only one thing you take away from this post, please let it be that. Every perspective you have is 94% wrong. And every perspective I have is 94% wrong. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. With this realization comes a whole truckload of humility! Because, how could I possibly think that my perspective is right for you? Especially considering that my personality type, INFJ, is the rarest of all the types. Okay, here’s a broader way of looking at it. Half the personality types have the cognitive function of intuition in their top two preferences, while the other half have sensing. But, intuition is far more rare than sensing. It’s estimated that only 30% of the population are intuitive personality types, while 70% are sensing personality types. So if you’re wanting to learn how to make music, my unique Song-Whispering method will deeply resonate with you if you’re an intuitive type, but if you’re a sensing type, then it probably won’t. And let me be clear, the method will work for everyone, but it will seem very strange to the 70% of people who are sensing types. And this is true for everything. There’s literally no topic that you can’t find equally qualified experts with diametrically opposed perspectives. Even when they agree on the same data points, their interpretations lead them to polar opposite conclusions. And I’m not exaggerating. Even topics we think are settled, are not. For example, did you know that there are medical doctors who say DNA does not exist? Or, did you know that there are physicists who say atoms and subatomic particles don’t exist. These things are supposed to be the building blocks of life and the universe, but doctors and scientists can’t even agree if they exist! So, when it comes to music, good luck trying to find a consensus as to how it should be made and taught! Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Having said all that, it’s absolutely vital to understand that this is not a problem. This is the beauty of diversity. Whatever experts say who have the same personality type as you (or a compatible type), will probably resonate with you. And whatever experts say who have incompatible personality types, will probably not resonate with you, no matter how much evidence they can present to support their claims. On that note, I invite you to visit HackMusicTheory.com and see if my approach to music resonates with you. If it does, then you can help yourself to a free download of my book 12 Music Theory Hacks to Learn Scales & Chords. It only takes about half an hour to read, then you’ll have a solid foundation of the basics. If you’re ready to go deeper, though, then I invite you to enroll in my online apprenticeship course, where you’ll learn one method to write unlimited songs in any genre. And yes, that’s the intuitive Song-Whispering I mentioned earlier. This method guides you through every step of the music making process, from blank screen to finished song. It’s truly life-changing – if you’re an intuitive type, like me! Lastly, I don’t paywall any of these posts, as I don’t want to exclude anyone. So if you can spare a few bucks, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s only the cost of one coffee per month for you, but if enough people join, I can pay the rent and keep helping you. If you’d prefer to make a one-off donation, though, that’s awesome too. I’m deeply grateful either way! To get involved, head on over to HackMusicTheory.com/Join. A heartfelt thank-you for your support. Happy learning, and welcome aboard the Songwriter’s Ark*.

Ray Harmony :)

*I visualize Hack Music Theory as a Songwriter’s Ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last.

Donate.

Help keep the Songwriter's Ark afloat.

Photo by Mart Production

About.

Ray Harmony is a multi award-winning music lecturer, who’s made music with Serj Tankian (System Of A Down), Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine), Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree), Devin Townsend (Strapping Young Lad), Ihsahn (Emperor), Kool Keith (Ultramagnetic MCs), Madchild (Swollen Members), and more.

Ray is also the founder of Hack Music Theory, a YouTube channel with over 10 million views and over 250,000 subscribers learning the fast, easy and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain’t no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs!

Photo by Marek Kupiec

Outro music by Ray Harmony, based on the music theory from GoGo Penguin "Everything Is Going to Be OK".

Podcast.

Listen below, or on any podcast app.

You Can’t Make Music without Using Theory.

“I don’t use music theory, because rules limit my creativity.” If I had a dollar for every time I heard someone say that in my 30 years of teaching music theory, I wouldn’t be living in a rented one-bedroom apartment, that’s for sure! The Oxford dictionary defines language as a “system of communication.” We can’t communicate through speech without using words, and we can’t communicate through music without using notes. The system of communicating with words is called grammar. The system of communicating with notes is called music theory. If you’re using notes, you’re using music theory. Therefore, it’s impossible to make music without using theory. The only choice songwriters have is whether to use it consciously or unconsciously. In other words, do we want to express ourselves consciously and therefore eloquently, or do we want to express ourselves unconsciously and therefore like two-year-olds? When I listen to a song made by someone who claims to not use music theory, I hear the equivalent of a musical two-year-old expressing themselves. There’s nothing wrong with that, if that’s your thing. After all, two-year-olds certainly have a unique way of conveying their emotions. Nobody would argue with that! However, if you prefer a maturer form of expression, then you’ll want to listen to someone with a deeper and more nuanced understanding of language. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. When it comes to speaking in our first language, we don’t have to consciously think about the system underlying our communication. That’s because we learned the language from such a young age. It’s second nature. Most babies say their first word around the age of 12 months. Imagine if we started music around that age, too. It would also be second nature by the time we’re five, which is when Mozart composed his first piece. For the rest of us, though, we have to learn music theory like we learn vocabulary and grammar of a second language. If someone thinks they can eloquently express themselves in a language they don’t know by simply using their ear, good luck to them, but even with luck on their side they’re still going to sound like a two-year-old. It’s the same when it comes to expressing oneself musically. If we want to make good music, we need to learn music theory. In other words, we need to learn the rules. That’s a dirty word nowadays, but rules can be good. For example, I live close to an elementary school, so the speed limit on the roads here is slow enough that grannies on bicycles overtake me. Is that rule bad? Of course not! If a kid runs out into the road, which they tend to do, they’re far more likely to get hit by a cycling granny than by my car. Rules can be good. And when it comes to music, the rules make our songs sound good. So if you’re still relatively inexperienced at making music, why wouldn’t you want to follow them? In the future, you can (and should) break the rules. But not yet. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Also, it’s worth remembering that when we first start driving, learning all the rules and remembering to follow them demands much of our energy and attention. After a few years of driving, though, it becomes rather natural. And after a few decades of driving, it becomes instinctual. Same with music theory. I can’t remember the last time I felt limited by the rules. Maybe about 32 or 33 years ago. It’s also worth mentioning a common and excruciatingly embarrassing situation many songwriters find themselves in, which is claiming that their music breaks the rules, when in actual fact it obeys them. I’ve come across countless examples of this, and it makes me cringe every time! Think about how obvious this problem is. How can anyone say they’re breaking the rules, unless they know the rules? Don’t be that songwriter who tries to act cool by saying they don’t use music theory. That’s not a choice anyone has. The only choice is whether to use it consciously or unconsciously. You decide. And on that note, if you’re new to making music (or if you want a refresher), I offer you a free download of my book 12 Music Theory Hacks to Learn Scales & Chords. It only takes about half an hour to read, then you’ll have a solid foundation of the basics. If you’re ready to go deeper, though, then I invite you to enroll in my online apprentice course, where you’ll learn one method to write unlimited songs in any genre. This method guides you through every step of the music making process, from blank screen to finished song. Happy learning, and welcome aboard the Songwriter’s Ark*.

Ray Harmony :)

*I visualize Hack Music Theory as a Songwriter’s Ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last.

Donate.

Help keep the Songwriter's Ark afloat.

Photo by Mart Production

About.

Ray Harmony is a multi award-winning music lecturer, who’s made music with Serj Tankian (System Of A Down), Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine), Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree), Devin Townsend (Strapping Young Lad), Ihsahn (Emperor), Kool Keith (Ultramagnetic MCs), Madchild (Swollen Members), and more.

Ray is also the founder of Hack Music Theory, a YouTube channel with over 250,000 subscribers learning the fast, easy and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain’t no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs!

Photo by Arzella BEKTAŞ

Outro music by Ray Harmony, based on the music theory from GoGo Penguin "Everything Is Going to Be OK".

Podcast.

Listen below, or on any podcast app.

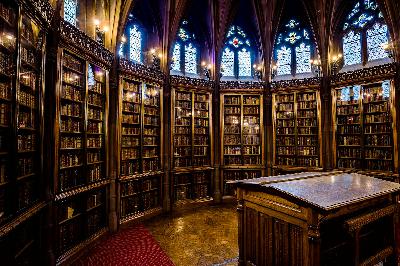

Hearing Music from the Future.

Materialist science tells us that we hear with our ears, and see with our eyes. But if that’s true, then how do we explain extra-ocular vision? If you haven’t come across this jaw-dropping phenomenon where blind (or blind-folded) people can see, look it up, and be prepared to have your worldview flipped. If you don’t know where to start, I recommend the work of theoretical physicist Dr. Àlex Gómez-Marín. Clearly the mainstream scientific explanation of how we see is sorely in need of an update. I suggest the same is true for hearing. And I appreciate that this topic is challenging for my materialist friends, but I invite you to research the scientific community’s dirty little secret, known as the replication crisis. This will open your eyes to the possibility that there’s more going on than we’ve been led to believe. My current working hypothesis for how we hear is something like this. When music is created, it’s stored in what I call God’s great library in the sky. You might call this the quantum field, if you’re scientifically-minded. Or the collective unconscious, if you’re psychologically-minded. Or the Akashic records, if you’re spiritually-minded. Whatever you call it, though, I believe it’s where human creations are eternally stored. When we hear music, its true source is the great sky library. And yes, most of the time this hearing is done through our ears. They sense vibrations in the air and transfer that information to our brain, where it’s transformed into music. But, that physical process can’t explain how it’s possible to hear music that isn’t there. For example, when people hear music during near-death experiences. Or when artists hear music in their dreams, which doesn’t exist in this world (yet), and then they wake up and record it. This brings the song into existence, which is how it ended up in God’s library in the first place. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. There’s many examples of songs that came to artists in this way. The most famous is probably “Yesterday” by The Beatles. Paul McCartney tells the story of how he woke up with that tune in his head, and couldn’t stop singing it throughout the day. He assumed it was a song he’d heard somewhere, so he kept singing it to people and asking them what song it was. But nobody recognized it. Eventually he realised that it wasn’t anyone else’s song, and excitedly got to work recording it. If my hypothesis is correct, what happened here is that Paul McCartney entered God’s sky library in his dreams and heard his own song from the future. The reason that’s possible is because this great library in the sky (aka the quantum field, or whatever you want to call it) is fundamental reality. Space and time emerge out of this foundational field. Therefore, all human creations from the past and the future already exist there. If we can enter God’s library, we can hear our unwritten songs from the future. We can then record them here and now, which in turn secures their place in the future. It’s a magical loophole. So, how do we enter God’s great sky library? Shhh... That’s how we enter. Silence. We enter by listening. Even if this whole hypothesis is completely and utterly false, it’s life-changingly useful. Seriously. As artists, we have big imaginations. So let’s imagine that our unwritten songs already exist in the quantum field. Our role is simply to attract them into our consciousness, and record them so other people can hear them, too. This removes all stress and anxiety from songwriting. Making music is no longer a painful birthing process, it’s now an exciting journey of discovery. It’s like going on vacation to a beautiful place you’ve never visited. You’re not worried about finding it. You’re not worried about travelling for ages only to realise the destination doesn’t exist. That’s because there’s no such thing as “destination block”. If you’re driving, you just follow the map. Or if you’re taking a bus, train or plane, you just get onboard and relax, or even go to sleep. Your destination will find you! Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Same with music. We can learn how to let our unwritten songs from the future find us. I call this song-whispering. I teach my method for doing this in my online apprenticeship course, but you can come up with your own way of doing it, too. It’s paradigm-shifting, and will forever change your relationship with songwriting. When you surrender to the knowledge that all your unwritten songs already exist in the field, you instantly feel a deep sense of calm and confidence. Also, you’ll begin to thoroughly enjoy the process of fishing for your future music in the quantum field! Lastly, if you’re new to making music (or if you want a refresher), I offer you a free download of my book 12 Music Theory Hacks to Learn Scales & Chords. It only takes about half an hour to read, then you’ll have a solid foundation of the basics. Understanding the language of music (aka music theory) is vital in becoming a fisher of future music. In order to write down and record the songs you’ll receive from the field, you need to speak the language of music. Happy learning, and welcome aboard the Songwriter’s Ark*. Ray Harmony :) *I visualize Hack Music Theory as a Songwriter’s Ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last.

Donate.

Help keep the Songwriter's Ark afloat.

Photo by Mart Production

About.

Ray Harmony is a multi award-winning music lecturer, who’s made music with Serj Tankian (System Of A Down), Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine), Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree), Devin Townsend (Strapping Young Lad), Ihsahn (Emperor), Kool Keith (Ultramagnetic MCs), Madchild (Swollen Members), and more. Ray is also the co-founder of Hack Music Theory, a YouTube channel with over 250,000 subscribers learning the fast, easy and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain’t no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs!

Photo by Michael D Beckwith

Outro music by Ray Harmony, based on the music theory from GoGo Penguin "Everything Is Going to Be OK".

Podcast.

Listen below, or on any podcast app.

You’re Listening to Music Wrong.

You’re Listening to Music Wrong. I am, too. We all are. It’s tragic, but we can fix it. Over the last 20 years, music has been devalued and demoted. It used to be the hero. Now it’s the sidekick. The soundtrack for working or socialising or whatever. However, if you’re a Gen Xer like me, you’ll remember spending countless hours sitting in front of your hifi captivated by great records, which physically spun around on your player. We listened with all our attention, doing nothing else. Just listening. Back then, listening to records was considered a hobby. Listening was an activity, because it was active. That’s the key word. Active. But as our attention got stolen away from us by smart phones, listening to records became passive. Music was no longer the main attraction. No, that was reserved for looking at our phones. Without us ever consciously choosing to do so, we relegated music to soundtrack status. That’s one of countless reasons why both myself and Kate (my wife) deleted all our personal and professional social media accounts back in 2015. We’re now celebrating our 10-year anniversary of not being on social media. It’s been one of the best decisions of our lives, by far! In fact, next month I’m celebrating my 19-year anniversary of being sober, and honestly, I rank these two celebrations as equals. But despite not being on social media, Kate and I are still listening to music wrong. And it’s not because of our phones. My phone is a decade old, so most apps won’t work on it. I’m not buying another smart phone, though, so when this phone stops working, I’ll be returning to a dumb phone. I’m much happier being a luddite. For now, at least, I’m still a smart phone owner, but the only app I use is Spotify. However, Spotify alone is enough to pull my attention in too many directions, and as a result, I almost never actively listen all the way through albums anymore. Don’t get me wrong, I listen to albums every day, but it’s while I’m working, exercising, reading, or eating. Music is never the main event, it’s the soundtrack. That’s depressing. That needs to change. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Every night I read for two to three hours. I love books! That’s why I only ever read paper books. Focusing on a non-fiction book for hours every day has been invaluable for maintaining my attention span. And I’ve been reading like this for many years. But despite being able to focus on an academic book for three hours, when I’m finished reading for the night and I open Spotify for my dedicated two-hour listening session, my focus instantly scatters. My attention span vanishes. It’s like a magic trick! What did Spotify do to my ability to focus? I’m sure all music streaming apps are the same, but as I use Spotify, I’ll be talking specifically about that app. So I first started using Spotify the month it launched in Canada back in 2014. It was life-changing! It was a music library beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. Like many Gen X teenagers in the ‘80s and ‘90s, I had a dream of one day having a whole room filled with records, floor to ceiling on every wall. Forget about that, though, now I had almost every record ever made in the palm of my hand. What sorcery was this? I loved it! I spent hours every day listening to albums that I’d always wanted to own, but buying records ain’t cheap, so my wallet had always been significantly smaller than my appetite for music. Spotify was my key to gaining access to the world’s biggest music library for a few bucks a month. It seemed too good to be true. And it kinda was, because after a few years, it all began to change. When I opened the Spotify app one day, I was suddenly confronted with all these podcasts. Podcasts!? They’re great, yes, but not in a music library. They’re a distraction from the artists and their albums. Against my better judgment, though, I tried a few podcasts. I was curious. Then the next day when I opened Spotify, I was confronted with new episodes from the podcasts I’d listened to, as well as other podcasts that were similar to the ones I’d listened to. They all looked fascinating, but how was I supposed to listen to all those podcasts and still have time for listening to albums? Then one day I opened Spotify and they’d added videos. Videos!? But I signed up for a music library! Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. As if all that wasn’t bad enough, Spotify then added audiobooks. For a booklover, this was (and still is) something I absolutely cannot say no to. Included in my Spotify plan, I get 15 hours of audiobook listening time every month. I have to use those hours, I can’t help myself. But that’s about half an hour a day that I used to spend listening to albums that I’m now spending listening to audiobooks. And these days when I open Spotify, I get new audiobook recommendations based on what I’ve listened to. That’s on top of all the new episodes from podcasts I listen to, as well as recommended podcasts that I haven’t listened to. And then there’s also all the new releases from artists I’ve listened to, as well as recommended artists that I haven’t listened to. Yet there are still only 24 hours in the day! So despite not being on social media, despite having a barely functional 10-year-old phone with only the Spotify app on it, and despite having an attention span that can focus on reading an academic textbook for three hours, I can’t stay focused when I open Spotify. There’s simply too many choices. It’s overwhelming. I feel like I’m trying to drink from a fire hose! That feeling reminds me of when I lived in London and I used to frequent this amazing Chinese vegan restaurant in Camden. It had an all-you-can-eat buffet, and every dish was delicious. I don’t think I ever left that place not feeling sick! That’s how I feel after my two hours of dedicated listening every night. Spotify is an all-you-can-listen-to buffet, and I leave afterwards having listened to part of an audiobook, a couple podcasts, and only a few songs from random artists that were recommended. I feel stuffed. And exhausted. It’s far from the dream-come-true music library I originally signed up for back in 2014. If you’re on social media and/or you have more than one app on your phone, I feel for you. I really do. I can’t imagine how stuffed and exhausted you must feel! It’s impossible to keep up, and trying is futile. So, I’ve designed a plan that will (hopefully) enable me to enter the daily all-you-can-listen-to buffet and exit two hours later, feeling nourished and rejuvenated. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Here’s the plan in a nutshell. Every night when I open Spotify for my two-hour session, I’m going to start by actively listening to one album all the way through. Simple plan, but this will protect my sacred music time. Also, another bad habit I’ve picked up in Spotify is reading the artist’s biography while listening to their album. And after that, I’ll usually look at their other albums, or worse, go down the rabbit-hole of similar artists. Not anymore, though. I’m going to put my headphones on, push play, put my phone down, close my eyes, and listen with all my attention. Just like the old days. By the way, if you feel inspired to try my plan for your listening sessions too, I recommend downloading the album, and then putting your phone on flight mode so you’re not disturbed by notifications. My phone is almost always on flightmode anyway, because I try to minimise the EMFs in my environment. The less EMFs, the less stress on our bodies and minds. Also, something I’ve been working on for a while is minimising the albums in my saved library. I’ve found that I get overexcited about saving albums, but then every time I go into my saved library I’m overwhelmed with all the options, and end up listening to a song here and a song there, but never going deep into one album. So, I’m trying to think of that space as my Desert Island Discs collection. It’s my own personal Hall of Fame. I’ve currently got around 80 albums saved, but it’s getting smaller every month. When I notice an album that I haven’t listened to in a while, I remove it from my saved library. The fewer albums there, the deeper I can explore each one. My goal is to get down to my Top 40 albums, and then I’ll use a “one in, one out” policy to maintain that size. It’s been a surprisingly fun project to whittle down these albums to my all-time favourites. I’ve also noticed that the fewer albums in my saved library, the more I value and appreciate each one. Interestingly, I have no albums saved from my childhood or teenage years. All my favourite albums have been ones I’ve discovered over the last few years. Not sure what that says about me, psychologically speaking, but hey, that’s a story for another day. And it’s not that I only listen to new music, it’s just that the recordings tend to be new. For example, my favourite recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations is from 2020. It’s performed by the Royal Academy of Music Soloists Ensemble, and conducted by Trevor Pinnock. Old music, but a new recording. This album is easily in my Top 10 all-time favourites. And speaking of great new albums. Yes, searching for these gems is like a treasure hunt. It’s thrilling! I love doing that. But it’s also one of the main reasons for my scattered focus. So, I’m designating a little time in every session for treasure hunting, but only after I’ve actively listened to one of my saved albums all the way through. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Back in the ‘80s and ‘90s, we used to listen to the same album hundreds of times. We’d know all the lyrics, all the melodies, all the riffs, all the drum beats, and even a lot of the drum fills too. It wasn’t uncommon for a Gen X teenager to be able to air-drum the fills while listening to their favourite albums. I miss knowing albums that intimately, and I miss the way that knowledge deepened our appr

The 4 Types of Artist. Which Are You?

Every song is born from an idea. So where do ideas come from? In other words: What or who is the cause of your imagination? Your answer to this question is tied to your worldview, and that determines what type of artist you are. The first type of artist believes that ideas come from the brain, and are a result of firing neurons. If you believe this, you’re what I call a natural artist. The second type of artist believes that ideas evolve from other ideas, and are a result of inspiration from other artists’ work. If you believe this, you’re what I call a humane artist. The third type of artist believes that ideas come from an impersonal universal mind, and are a result of connecting to this unified field. If you believe this, you’re what I call a quantum artist. The fourth type of artist believes that ideas come from a personal God (or gods), and are a gift from his spirit (or the spirits). If you believe this, you’re what I call a supernatural artist. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Each worldview encompasses vast diversity, but artists within each type have a common belief of where their ideas come from. For example, the supernatural category includes Christians and hunter-gathers. On the surface they seem drastically different, but a deeper look reveals that both groups are living in a supernatural reality. On that note. It may come as a surprise to artists in the other three categories, but up until very recently in human history, everyone was in the supernatural group. If you’re interested in learning about this fascinating topic, I recommend the excellent book The New Science of the Enchanted Universe: An Anthropology of Most of Humanity by the late, great anthropologist Marshall Sahlins (1930–2021). Also, I appreciate that grouping all artists into these four worldviews neglects some other beliefs. For example, maybe ideas come from people in the future who’ve invented technology that transmits them back to us. Or, perhaps ideas are beamed down to us from ancient aliens living above the firmament. Or, maybe ideas float to us on the air breathed out by an advanced race living beyond the icewall. I could go on, but you get the idea. These are all valid hypotheses, and should not be discounted unless they can be disproven. However, for the sake of brevity, I’ll limit this to the four broad worldviews: natural, humane, quantum, and supernatural. Hopefully one of these will resonate with you. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Also, each artist type can include the worldview of the previous type(s). For instance, a humane artist can also believe what a natural artist believes. This worldview sees ideas as a result of neurons firing in the brain, but that firing was due to an interaction with other artists’ work. If you believe this, you’re still a humane artist, you’ve simply included the natural artist’s worldview. And for the record, no type is better than any other. That would be like saying the marathoner Eliud Kipchoge is a better runner than Usain Bolt, because Bolt stops after he’s run a hundred meters. That’s ridiculous! They’re two of the greatest runners of all time. They’re running different races, though, so it’s pointless to compare them as runners. Same with artists. Their worldviews do not determine how good their art is. Their ideas determine that! It’s all about ideas. And that’s exactly why typing ourselves is important. Once we know what type of artist we are, we can know how to live up to the potential of our type. This will result in better ideas, and better ideas give birth to better songs. So which type of artist are you: natural, humane, quantum, or supernatural? Now that you’ve typed yourself, here’s how to live up to your artistic potential. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. If you’re a natural artist, you need to prioritise the nurturing of your brain. You can do this by sleeping enough, exercising daily, eating healthy food, drinking plenty of filtered water, getting fresh air and sunshine, grounding and minimizing EMFs in your environment, and daydreaming in a park (with your phone turned off). If you’re a humane artist, you need to prioritise the nurturing of relationships with other artists. You can do this by meeting up with creative people face-to-face on a weekly basis and sharing ideas, or even better, collaborating. But, you can also be inspired by reading biographies of your favourite artists, both living and dead. If you’re a quantum artist, you need to prioritise the nurturing of transcendence. You can do this by cultivating a daily meditation ritual, practising yoga and/or qigong, chanting, and listening to sublime music with headphones on and your eyes closed. I recommend the breathtaking album Vivaldi: Stabat Mater by Jakub Józef Orliński. If you’re a supernatural artist, you need to prioritise the nurturing of worship. You can do this by praying throughout the day, giving thanks for all your blessings, singing praises, contemplating God (or the gods), reading scripture and other books in your tradition, listening to sacred music, dancing, and doing pilgrimages. So, whatever type of artist you are, I encourage you to include some (or all) of these practices in your daily routine. And let me know in the comments what type you are, and which practices resonate with you. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Lastly, please note that using AI to get ideas is not suggested for any of the types, because outsourcing your thinking never ends well. If you’re struggling to make music, the solution is not AI, it’s music theory. Music theory is the language of music, so when you learn how to use it, you can easily express yourself through melodies, harmonies, and rhythm. And it’s fun too, when you know how to do it! If you’re new to music (or if you want a refresher), I offer you my free book 12 Music Theory Hacks to Learn Scales & Chords. It takes about half an hour to read, then you’ll have a solid foundation of the basics. And if you’re inspired to go deeper, then I invite you to join my online apprenticeship course. You’ll learn every step of the music making process, from blank screen to finished song. Happy learning, and welcome aboard the Songwriter’s Ark*. Ray Harmony :) *I visualize Hack Music Theory as a Songwriter’s Ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last.

Donate.

Help keep the Songwriter's Ark afloat. Photo by Mart Production

About.

Ray Harmony is a multi award-winning music lecturer, who’s made music with Serj Tankian (System Of A Down), Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine), Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree), Devin Townsend (Strapping Young Lad), Ihsahn (Emperor), Kool Keith (Ultramagnetic MCs), Madchild (Swollen Members), and more. Ray is also the co-founder of Hack Music Theory, a YouTube channel with over 250,000 subscribers learning the fast, easy and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain’t no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs! Photo by Pixabay Outro music by Ray Harmony, based on the music theory from GoGo Penguin "Everything Is Going to Be OK".

Podcast.

Listen below, or on any podcast app.

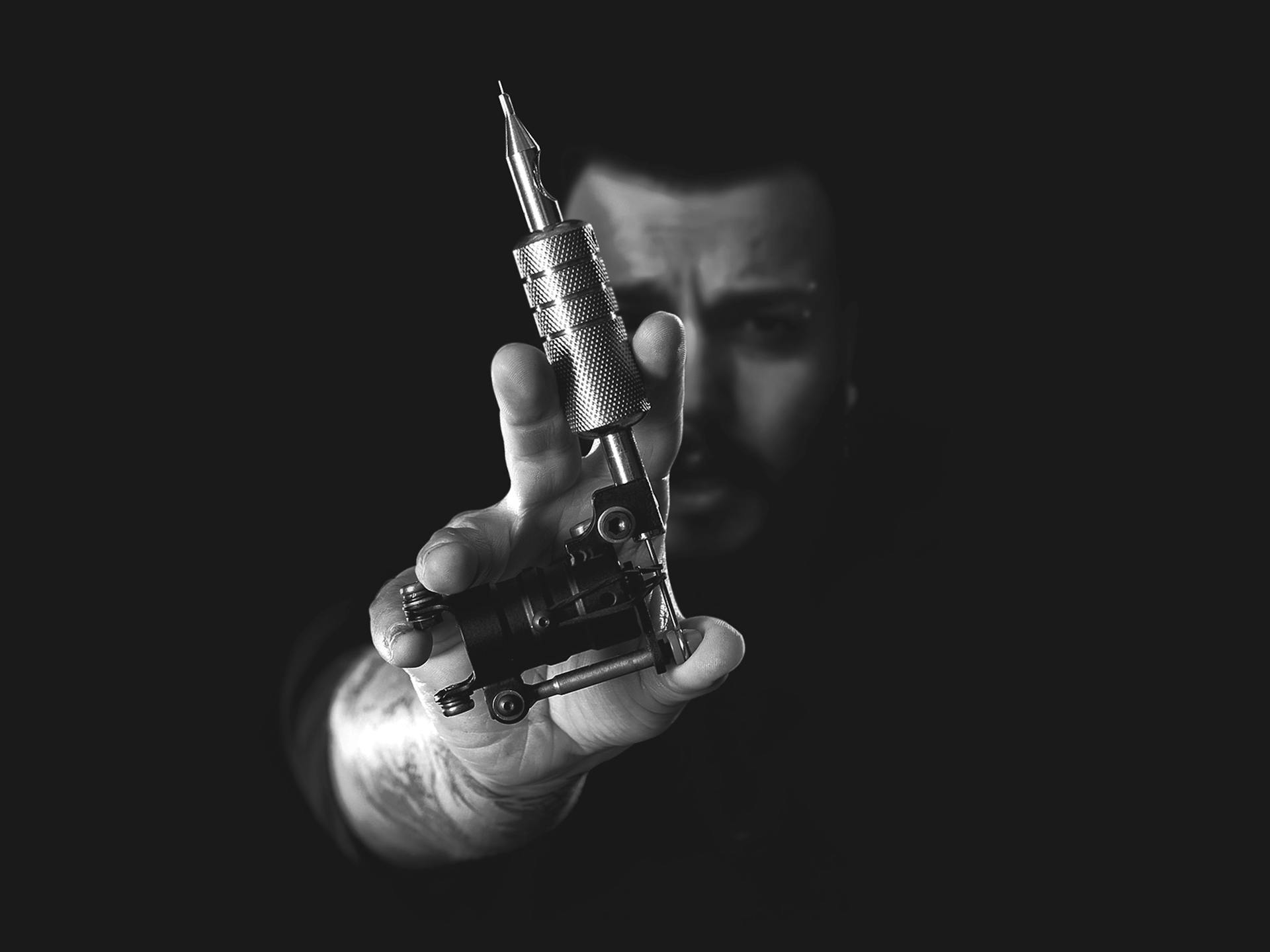

AI Is Not a Tool. Stop Calling It That.

I’ve tattooed myself. Three times! You know what? It hurts a whole lot more when you do it to yourself. You know what else? It looks terrible, too. Why? Because a tattoo machine is a tool that an artist uses to create images in the skin. I had the tool, and I even had the imagination to come up with a creative idea for the image, but I did not have the skill. So, when I drew it, it was a mess. And when I tattooed it, it was a painful mess! It was a thoroughly fascinating experience, though, and I did it under the supervision of a world-class tattooer. But, because I had not learned the skills and spent thousands of hours practicing, there was no hope of creating a good tattoo. Throughout human history, tools were useless without the accompanying skills. And I’m going to argue here that they still are. If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll have noticed how the definitions of words are changing at a rapid rate nowadays, so you need to keep your wits about you. The Oxford Dictionary defines a tool as “a thing that helps you to do your job or to achieve something.” The key word in that definition is “helps”. Whether someone uses AI to generate a whole song or only the initial idea, AI is not helping them, it’s doing the skilled work for them. A tattoo machine is a tool that helps the artist put their image in the skin. If the machine draws and tattoos the image on its own, then it’s not helping the tattooer, it’s replacing them. The skills are now in the machine, not the human. By definition, that machine is no longer a tool, it is the tattooer. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Same with music. If a songwriter uses a digital audio workstation (DAW) on their computer to express their imagination and capture their ideas, then it’s a tool. If you use this software, you’ll know that when you open it, you’re greeted by a blank screen. Same for authors. When they open a new document in their word processor, they don’t find ideas for their next story, they find a blank screen. That’s because word processors and digital audio workstations are tools. They help. Nothing more. All the ideas and skills are exclusively in the humans. It’s a common defence from AI users that they only use it to get the initial idea, and then they write the song themselves. But, using our imagination to come up with that initial idea is probably the most difficult part of the songwriting process. So using AI to get the initial idea is cheating. And more importantly, every time a songwriter does this, they’re cheating themselves out of their own imagination. If we don’t exercise our imagination, we lose it. When a generation of people lose their imaginations, and then go on to have children who are born into a reality without imagination, it’s a very different world. Is that a world you want? Now, if someone chooses to use AI instead of their imagination, that’s up to them. But it’s a lie to say that AI is a tool that helps them come up with ideas. No, it’s not a tool. It’s a replacement for their imagination. That’s a whole lot more than a tool! Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Also, songwriters need to have the skills (and perseverance) to develop their initial idea into a full song. There are countless skills involved in going from a blank screen to a finished song. Even just that one skill alone of knowing when a song is finished, is difficult to learn. A tool, like a digital audio workstation or a guitar, helps us express our imaginations. By definition, if it comes up with the ideas or does the skilled work for us, then it’s not a tool, it’s the songwriter. So the next time you hear a songwriter (or anyone in the creative arts) saying: “AI is just a tool”, please correct them. AI is not a tool, it’s The Great Reset of Skills & Ideas. And the more this “AI is a tool” narrative is pushed, the more vital it is that we hold on to original definitions. If we lose touch with those, we lose touch with reality. If this has inspired you to learn the skills so you can express your ideas, then I offer you my free book 12 Music Theory Hacks to Learn Scales & Chords. It only takes about half an hour to read, then you’ll have a solid foundation to start making music. And if you’re already a songwriter but you’re frustrated because your music isn’t as good as you know it can be, then I invite you to join my online apprenticeship course. You’ll learn every single skill you need to go from a blank screen to a finished song. Happy learning, and welcome aboard the Songwriter’s Ark*. Ray Harmony :) *I visualize Hack Music Theory as a Songwriter’s Ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last.

Donate.

Help keep the Songwriter's Ark afloat. Photo by Mart Production

About.

Ray Harmony is a multi award-winning music lecturer, who’s made music with Serj Tankian (System Of A Down), Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine), Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree), Devin Townsend (Strapping Young Lad), Ihsahn (Emperor), Kool Keith (Ultramagnetic MCs), Madchild (Swollen Members), and more. Ray is also the co-founder of Hack Music Theory, a YouTube channel with over 250,000 subscribers learning the fast, easy and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain’t no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs! Photo by barış erkin Outro music by Ray Harmony, based on the music theory from GoGo Penguin "Everything Is Going to Be OK".

Podcast.

Listen below, or on any podcast app.

AI Is Killing Music! This Is How We Save It.

Hardly anything is real anymore! And that includes most people. They walk around staring at their phones with earbuds in, ignoring the reality all around them and instead choosing to live in their screen’s virtual reality. Regardless of what their senses tell them, if their screen says it’s real, then it’s real. If their screen says it’s true, then it’s true. On top of all the propaganda made by humans, the internet is also overflowing with AI misinformation and deepfake videos of people who are not themselves saying things they never said. And now, music streaming services are full of AI-generated songs by artists who didn’t write them, because the artists don’t even exist. Yet every day more and more humans choose virtual over real, screens over trees, and AI over elders. If you’re like me, and you’re also horrified by this brave new AI world, it’s easy to get overwhelmed with grief for the loss of our old world where humanity mattered. But focusing on the past and everything we’ve lost makes us feel bad. And focusing on the future and how robots are gonna steal our humanity (and our jobs!), makes us feel worse. So what do we do? We continue to bring awareness to this problem, while simultaneously creating solutions in the form of a parallel system. So let’s roll up our sleeves and get to work right here in the present. How? We make music real again. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. That’s no easy task, though, because all new music cannot and should not be trusted. It’s similar to how the singing on recordings could no longer be trusted after the release of auto-tune in 1997. If you hear a recording from before ‘97 and the singer sounds good, then you know they’re actually a good singer. Unless it’s a Milli Vanilli lip-syncing type thing, but still, there were good singers on those recordings, it just wasn’t Milli Vanilli. And obviously not every singer used auto-tune on their recordings after ‘97. However, I personally know studio engineers who secretly tuned vocals overnight, so when the singer arrived back in the studio the next morning, they wouldn’t even know their vocals had been tuned. They’d just be thinking: Wow, I nailed that! So if the singers don’t always know they’ve been tuned, how can we? Now in the 2020s, we’re dealing with the songwriting version of this. If you hear a good song from before the ‘20s, then you know it was written by good (human) songwriters. Even if it was written by ghost writers, they’re good (human) songwriters. But now we can no longer trust the songwriting behind recordings. And that goes for new albums by old-school Gen X bands, too. They could just as easily have gotten AI to write the songs, and then learned how to play them afterwards. Or perhaps the songwriter in the band was under immense pressure to write new songs that would become modern classics, so at home in secrecy they got AI to write the songs and the lyrics. The rest of the band wouldn’t even know they were AI-generated songs, so how can we possibly know? By now you might be thinking: Why does it matter? If the song is good and I enjoy it, what’s wrong with it being AI-generated? Everything is wrong with that, because every time we choose AI over humans, we take another step into transhumanism. This is about a lot more than music! Even small choices make a difference, like choosing a check-out in the grocery store with a human clerk instead of self-checkout, and looking them in the eyes, smiling, and saying: Hello friend, how are you? Human connection is the only way to maintain our humanity. Music is one of the most powerful ways for humans to connect. Every time we listen to an AI-generated song, instead of connecting with humans, we’re being connected to the machine. And yes, doing the research to ensure we’re listening to real music requires time and effort, but it’s worth it, just like it’s worth researching what we eat in order to ensure that it’s real food and not full of chemicals. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. So how on earth can we make music real again? Well I’m glad you asked, because I’ve had an idea! The only way to save music is to re-establish the trust that has been lost. And the only way to do that is to verify and certify songs that are human-made, in the same way old-school farmers get their food verified and certified as organic. That process is so expensive, though, that many organic farmers can’t afford it and so their food can’t be certified. Therefore, I suggest we use fan verification instead. As opposed to losing artists money, this would actually create a new income source for them. Here’s how I envision the process unfolding. Seeing is believing, so in order to know that a song was made by humans, we need to see them writing it from start to finish. I’ve actually done this twice before in my online apprenticeship courses. Every minute of the songwriting process was filmed. This is not an edited behind-the-scenes documentary, it’s the entire warts-and-all songwriting process, from blank screen to finished song. This video footage is proof that I wrote those songs. But with AI’s deepfake capabilities, video evidence can no longer be trusted either. In order for fans to know that a song is human-made, the artist needs to write it live in front of them. This would be nothing like a concert, though, it would be more like a weekend workshop. The event would be filmed, and the fans would sign a document verifying that it was real and not deepfaked. The artist could even do this as a songwriting tour, which would establish eyewitnesses in many different cities. The creative process is magic, so having fans sharing in this would be the most thrilling gift artists have ever offered their fans. And as this would be such a momentous opportunity for the fans, the cost of a ticket could be a significant sum. Think about it. How much would you pay to watch your favourite artist writing their new album live, right in front of you. It’s a priceless offer! And to write a full album, an artist would obviously need many of these live songwriting sessions. This will not only form intimate artist-fan relationships like never before, but it will also create a new and lucrative income stream. Fans who buy tickets to songwriting sessions will inevitably be superfans, and therefore willing to pay handsomely for the privilege of witnessing the magic unfold live. Usually when writing an album artists hide themselves away for months, while their income dwindles as a result of not performing live. However, with these live songwriting sessions, artists would get paid not only for performing, but for writing too. And most importantly, they’d end up with an album full of songs that have each been verified and certified as human-made. The final part of the process would involve rehearsing and recording the songs. Then the album would be released in tandem with the video footage of all the live songwriting sessions, as well as the fan-certified documents. Next, the artist would shift into performing mode and take to the stage, where they would be greeted by trusting fans who are confident in the knowledge that the songs are human-made. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Now let’s address the elephant in the room. If you’re a songwriter, the idea of having to write in front of an audience is probably filling you with dread. I get it, I’ve done this twice before on live webinars. Know this, though, the fear disappears as soon as you get in the flow, and then the energy and excitement is utterly exhilarating! If you want to feel truly alive, write a song live. Yes it takes courage, but all the best things in life do. And remember, writing music is simply expressing ourselves. That’s not scary. We do it all the time in conversations. If you talk to someone in your first language, you feel comfortable expressing yourself. But, if you try communicating in a language you’re not fluent in, then it’s an anxious and frustrating process. That’s where music theory comes to our rescue. If we understand the language of music, then writing songs is simply a case of expressing ourselves using that language. So if you want to learn the language of music, then I offer you my free book 12 Music Theory Hacks to Learn Scales & Chords. You can read it in about half an hour, then you’ll have a solid foundation. Even if you’re not interested in writing your own songs, this book will help you appreciate music in a far more meaningful way. And if you’re looking to become fluent in the language of music, then I invite you to join my online apprenticeship course. That’s where you’ll watch the videos of me writing two whole songs from start to finish, while also teaching every step of the process, so you can learn and use my method in your own original way. Happy learning, and welcome aboard the Songwriter’s Ark*. Ray Harmony :) *I visualize Hack Music Theory as a Songwriter’s Ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last.

Donate.

Help keep the Songwriter's Ark afloat. Photo by Mart Production

About.

Ray Harmony is a multi award-winning music lecturer, who’s made music with Serj Tankian (System Of A Down), Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine), Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree), Devin Townsend (Strapping Young Lad), Ihsahn (Emperor), Kool Keith (Ultramagnetic MCs), Madchild (Swollen Members), and more. Ray is also the co-founder of Hack Music Theory, a YouTube channel with over 250,000 subscribers learning the fast, easy and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain’t no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs! Photo by Nano Erdozain Outro music by Ray Harmony, based on the music theory from GoGo Penguin "Everything Is Going to Be OK".

Podcast.

Listen below, or on any podcast app.

AI Saves Us Time. That’s Bad!

Time is our only non-renewable resource. People talk about “spending” time and “spending” money, but these two types of spending are opposite. We can always make more money, but we can never make more time. Therefore, the greatest, most valuable gift we can give someone is our time. Think about it. No matter how much money you spend on a gift for someone, unconsciously you both know that it’s a renewable resource. But if you spend a full day with that person giving them your full attention (in other words, with your phone turned off), they will feel like the most special person in the world. Here’s another example. If you’re a parent (or a grandparent) of a young child, your fridge door is probably plastered with dodgy drawings. And one of your favourites is almost certainly a picture of yourself, despite the fact that your head is bigger than your torso, your hair looks like it’s been transplanted from the head of Pennywise the clown, and you’re missing a few fingers. But, how much do you love that drawing? More than words. Now imagine a different scenario where your child (or grandchild) gives you a gift of an AI-generated picture of you, which is “perfect”, or so we’re told by the AI-pushers. Which picture do you prefer? The hand-drawn clown you, or the picture-perfect AI you? Exactly. But why do you love the “imperfect” hand-drawn picture instead of the “perfect” AI-generated picture? Because, your child (or grandchild) spent time drawing it for you. And our time is the greatest, most valuable gift we have to offer. So what’s this got to do with music? Whenever someone uses AI in the songwriting process, they’re depriving the world of their greatest gift: time. It’s the equivalent of the kid giving his parents (or grandparents) an AI-generated picture instead of a hand-drawn picture. Every time either of these things happen, a piece of humanity dies. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. So yes, using AI in the songwriting process saves us time, but spending time is the whole point. Music, without time spent making it, is a pointless contribution to the world. It has no value and no worth, and the world is far better off without it. But we’ve been fed the lie of convenience, and the masses have swallowed it hook, line and sinker! Convenience is the new idol. Saving time, the new goal. But saving time does not make our lives better. Spending time in the right way does. Think about it. Let’s say you’ve got a fun day-out planned with your best friend. Now what if I told you that I can save you a full day of your life, which you can get back and then use for something else. You see where I’m going with this, right? So, instead of you going on your fun day-out, I’ll go for you. There, I just saved you a full day. You’re welcome. Wait, you’re not thanking me? But I saved you a full day! As this thought-experiment shows: our lives are not improved by saving time, they’re improved by spending time wisely. We need to embrace meaningful inconveniences, like the process of writing a whole song from start to finish, all on our own. When we do difficult creative projects like this, we become better humans and the world becomes more humane. So, if you’re feeling inspired to embrace the inconvenient and time-consuming act of making music, then you can get started right now by reading my free book 12 Music Theory Hacks to Learn Scales & Chords. And if you wanna learn my secret method of Song-Whispering, which is a way for your song to guide you so it feels like it’s writing itself, then I invite you to join my online apprenticeship course. Happy learning, and welcome aboard the Songwriter’s Ark*. Ray Harmony :) *I visualize Hack Music Theory as a Songwriter’s Ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last.

Donate.

Help keep the Songwriter's Ark afloat. Photo by Mart Production

About.

Ray Harmony is a multi award-winning music lecturer, who’s made music with Serj Tankian (System Of A Down), Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine), Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree), Devin Townsend (Strapping Young Lad), Ihsahn (Emperor), Kool Keith (Ultramagnetic MCs), Madchild (Swollen Members), and more. Ray is also the co-founder of Hack Music Theory, a YouTube channel with over 250,000 subscribers learning the fast, easy and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain’t no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs! Photo by Jordan Benton Outro music by Ray Harmony, based on the music theory from GoGo Penguin "Everything Is Going to Be OK".

Podcast.

Listen below, or on any podcast app.

AI Can't Make Music.

AI can’t make music. Let me explain… The reason almost everyone thinks AI can make music, is because the definition of music has changed. As a side note, it’s interesting how more and more definitions seem to be changing nowadays, isn’t it? But that’s a story for another day… What’s important to us here is the original definition of music. In other words, what music meant to our hunter-gatherer ancestors. To them, music was an ineffable expression of the human experience, shared through pitched and rhythmic patterns. This was the universal meaning of music from the beginning of humankind. There are mystical elements too, which are vital, but that’s also a story for another day. So, how did the definition of music change? It all began when music was corralled into the concert hall about 300 years ago, which turned it into a performance. And with that, it was no longer something everyone actively participated in. There were now active performers, and passive listeners. This was the fork in the road. From that point on, music was a product that could be monetized through admission fees. This was the first major definition change. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. Now, as with all progress, there are many benefits. However, knowing the costs of those benefits is essential in weighing up the pros and cons of the progress. Yes, there was a long list of benefits from domesticating wild music and transforming it into tame performance art, but the costs were severe. For example, singing used to be something that people did communally. And they did it while moving in unison. Whether it was bushmen singing and dancing around a fire, or baptists singing and swaying in a church, the mental, physical, spiritual, and societal health benefits of this ritual cannot be overstated. And all that was lost when singing became something that the chosen choir did, while everyone else shut their mouths and sat on their asses. Sadly, though, those losses are only the tip of the iceberg. When sound recording was invented less than two hundred years ago, it was the active musicians who were next in line to be disempowered. For the first time in human history, it was now possible to listen to music without anybody making it. It’s impossible for us to imagine how utterly bizarre that must’ve been. There were no musicians playing, yet people were hearing music. Where was it coming from? Mad times! That was the second major definition change. Music had now been corralled into a disc made of resin. And these could be mass-produced and sold. Ka-ching! Instead of having to pay musicians for every concert, they could now be paid for one concert that was recorded, and then that recording could be sold an unlimited amount of times. Once again, a cost-benefit analysis for humanity should have been done. But it wasn’t. As always, the masses rushed headlong into a future that was even more unnatural, without even pausing to think about the repercussions. Sound familiar? Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. And it’s worth stating clearly here that a recording of music is not music, it’s a recording. Just like a photo of a car is not the car. Think about it. If you want a new car and I give you a photo of that car, do you now have the car? Obviously not. You have an image of the real thing. Same with music. Think about it. If you want to hear the latest song from your favourite artist, you’ll open your music app and listen to it. But are you actually listening to the song? No. You’re listening to a recording of the song. That idea sounds crazy to us in the 21st century, but that’s only because the definition of music has changed twice already. That brings us to the present, where we’re being told that AI can make music. But hopefully by now you can see why that’s a lie. AI can’t make music, because music is an expression of the human experience. AI can’t have the human experience, therefore AI can’t make music. The robots can do lots of things, yes, but making music is not one of them. And even if you believe AI will become conscious one day, it can never be human, so it will never be able to make music. And yes, animals are conscious, and some species (like birds) have something similar to music. But that’s not music either, for the same reason: birds are not expressing the human experience. So let’s not get our definition of music confused by the mainstream narrative about AI. Music can only be made by humans. End of story. These definition changes have resulted in us giving away our creative power as humans who actively make music. Over the last few centuries, we’ve turned into powerless, passive consumers of recordings. And now we’re not even listening to recordings anymore, we’re consuming soulless AI-generated sonic content. So, if you’re feeling inspired to take your power back and become an active music maker, like all our ancestors were, then you can get started right now by reading my free book 12 Music Theory Hacks to Learn Scales & Chords. And if you’re already making music but you’re frustrated because it’s not as good as you’d like, then I invite you to join my online apprenticeship course. Happy learning, and welcome aboard the Songwriter’s Ark*. Ray Harmony :) *I visualize Hack Music Theory as a Songwriter’s Ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last.

Donate.

Help keep the Songwriter's Ark afloat. Photo by Mart Production

About.

Ray Harmony is a multi award-winning music lecturer, who’s made music with Serj Tankian (System Of A Down), Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine), Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree), Devin Townsend (Strapping Young Lad), Ihsahn (Emperor), Kool Keith (Ultramagnetic MCs), Madchild (Swollen Members), and more. Ray is also the co-founder of Hack Music Theory, a YouTube channel with over 250,000 subscribers learning the fast, easy and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain’t no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs! Photo by Pavel Danilyuk Outro music by Ray Harmony, based on the music theory from GoGo Penguin "Everything Is Going to Be OK".

Podcast.

Listen below, or on any podcast app.

Making Music is Hard. Why Bother?

I never thought this day would come. But here it is. After 30 years of teaching music to thousands of students, I’m facing a previously unimagined challenge: convincing people who want to make music that they should learn how to do it. Never in human history has there been any other option. But now, there are robots that can make “your” music for you. Is it yours if you didn’t write it? No, but the masses embracing AI-generated music don’t seem bothered by that fact. There are only 12 notes in music, so it’s relatively easy to understand. But making music is not as easy. And making good music is rather hard. That’s because there are infinite ways to combine those 12 notes melodically and harmonically. And then there’s the eternal world of rhythm. Infinity x eternity. That’s a lot of options! Yet despite the never-ending options, for a beginner songwriter it usually feels like every combination they choose ends up sounding a bit rubbish. Where are all those great combinations hiding? Only years of exploring will begin to reveal them. Photo by Gerd Altmann And therein lies the problem. In the good ol’ days before AI, if someone wanted to make music, there was only one option: learn how. But in this brave new world, why bother spending years learning and practising, when you can just get a robot to do it for you? No need for learning, practising, or even patience. A complete beginner can use AI to make a song (and the cover art too), then upload it to Spotify. All before breakfast. And that brings me back to my new challenge of convincing people that learning how to make good music is worth the effort. That is my new passion. Because, we know from history that it only takes one generation to lose a skill. If humans can’t be convinced that making music is a skill worth preserving, it will be lost forever. Just another fossil from those less “civilized” people of a bygone era. You know, those poor people who had to walk everywhere, grow their own food, and make their own music. Yeah those people. Wow, sucked to be them! Yes they were much happier and healthier than us, but still, no smart phones? Sucked to be them! Photo by RDNE Stock project So, why bother writing your own music? Because the process is what’s valuable, not the end result. The process of expressing ourselves by making music improves our mental health, our spiritual health, and even our physical health. And sharing our music in-person connects us to our fellow humans in a way that nothing else does. If all that’s not enough, how about this: making music is playful and fun! Remember those things? It’s what we used to do before smart phones were invented. Subscribe to get the latest posts in your inbox. There’s one caveat, though. It’s only fun if you know how to do it. If you don’t, then it’s frustrating. And I suspect that’s the main reason why people are turning to AI. But AI is not the solution. The solution is learning and practising. And the more you learn and practice, the more fun the songwriting process becomes. It’s like exercising. When we first start, it’s horrible. Our muscles burn, our lungs burn, and every fibre of our being shouts “STOP!” Sadly, most people do. But for the ones who persevere, something magical happens. Each week the burning gets less, and the shouting gets softer. Then one day right in the middle of an exercise session, we suddenly realize our inner voice is shouting: “GO! GO! GO!” It usually takes a few months to break through that barrier, but when we do, the fun makes it all worthwhile. Photo by Barbara Olsen I want you to enjoy that post-breakthrough fun with your music. There’s no better feeling. But it requires trust. And I’m not asking you to trust me. I’m asking you to trust yourself, and to trust the journey. Until you reach that breakthrough, it’s hard. But if you give up before then, you’ll never reap the health rewards. And you’ll miss out on a ton of fun, too! With this new challenge in mind, I’m now visualizing Hack Music Theory as a Songwriter’s Ark, where all the music making skills are being preserved through this global AI flood. The flood shall pass. The skills will last. So, if you’re feeling inspired to get onboard, I recommend reading my free book 12 Music Theory Hacks to Learn Scales & Chords. And if you’re already making music but it’s not as good as you’d like, I recommend my online apprenticeship course. Happy learning, and welcome aboard the Songwriter’s Ark. Ray Harmony :)

Donate.

Help keep the Songwriter's Ark afloat. Photo by Mart Production

About.

Ray Harmony is a multi award-winning music lecturer, who’s made music with Serj Tankian (System Of A Down), Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine), Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree), Devin Townsend (Strapping Young Lad), Ihsahn (Emperor), Kool Keith (Ultramagnetic MCs), Madchild (Swollen Members), and more. Ray is also the co-founder of Hack Music Theory, a YouTube channel with over 250,000 subscribers learning the fast, easy and fun way to make music without using AI, cos it ain’t no fun getting a robot to write “your” songs! Photo by Wout Nes Outro music by Ray Harmony, based on the music theory from GoGo Penguin "Everything Is Going to Be OK".

Podcast.

Listen below, or on any podcast app.

How to Write aCatchy Melody.

Free PDF Tutorialincludes multitrack MIDI file

If the link above does not work, paste this into your browser:https://hackmusictheory.com/album/2877864/catchy-melody

Intro.

British band Glass Animals are absolutely massive! At the time of writing this, they’re ranked #257 in the world on Spotify. Most artists as famous as them have achieved their success as a result of an obsessive striving for celebrity. However, Glass Animals seem to be obsessed with making catchy music instead. And not only that, their music is surprisingly creative for a band as successful as them. If you’ve been doing our Hack Music Theory tutorials for a few years, you’ll know that we don’t usually cover “celebrity artists”. The reason for that is because (nowadays) there’s an inverse correlation between the success of an artist and the creativity of their music. For an artist to achieve a fanbase of tens of millions, their music needs to appeal to the masses. And most people (nowadays) want “sugary” ear-candy music that’s pleasantly predictable, i.e. boring, bland background music. So why are we doing a tutorial on such a huge band? Well, Glass Animals’ new single “Creatures in Heaven” is a masterclass in catchy melody writing. The lead melody in their chorus has a whole bunch of creative hacks, as well as a very clever twist in its tale. So, inspired by “Creatures in Heaven”, here’s our 6-step method for writing a great melody that’s catchy enough for the masses. But first… Tea!

Step 1. The Chords

Open your DAW, leave the time signature on 4|4, but change your tempo to 80 BPM. Next, create a four-bar loop on your melody track, with a 1/16 grid. Okay so you may be wondering why the first step in a melody tutorial is… the chords?! Well, all great melodies are written over chords, or implied chords (chords are “implied” when they’re not played separately but their notes are incorporated into the melody instead). The reason it’s best to write a melody over chords is because it gives the melody a harmonic progression. Without this progression, the melody will sound mind-numbingly boring, as it won’t go anywhere harmonically. The difference is night and day. It’s like walking through a beautiful forest along the ocean compared to walking on a treadmill in a stinky gym. There’s no comparison! So let’s get our chord progression written, that way we’ve set ourselves up to write a great melody. Glass Animals are in the key of D major for their chorus (so we’ll use it too), and they use four chords in their progression (so we’ll do that too). D Major (notes)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

D

E

F♯

G

A

B

C♯

D Major (chords)*

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Dmaj

Em

F♯m

Gmaj

Amaj

Bm

C♯dim

As you probably know (or as you’ll hear if you play it), the diminished chord is crazy dissonant. It’s safe to say that using C♯dim ain’t gonna appeal to the masses, so take that off your menu. But other than that, you can use whatever you want. Glass Animals use all three major chords, and only one minor. Playing three major chords in a major key gives their chorus a wonderfully uplifting vibe. So, think about your balance between major (happy) and minor (sad) chords. Also, think about the order of your chords. Glass Animals play the root chord (Dmaj) second. This detracts attention from it and creates a more fluid atmosphere. We played Dmaj last, though, which creates a more final ending. You can play Dmaj wherever you want, but consider where you want to draw people to the “home” chord. Here’s our progression: Gmaj → Bm → Amaj → Dmaj *If you need help working out the chords in a key, read Hack 10 in our Free Book. Once you’ve chosen your four chords, draw in the root note of each chord for a full bar (in a low octave). These roots will provide harmonic reference for your melody, which you’re gonna write above. This way you’ll be able to hear the relationship between each note in your melody and its accompanying chord. When you’ve finished writing your melody, mute these low roots. Then, create another track specifically for your progression, and draw in each full chord (i.e. 1, 3, 5). Root note of each chord in progression (key note, D, highlighted)

Step 2. The Drama

Great melodies contain drama, and there’s no better way to bring the drama than by using a big interval.* You see, larger intervals create intensity, while smaller intervals create continuity. You need both. In fact, you need a lot more smaller intervals than bigger intervals. However, if your melody contains only small intervals, it’ll be awfully boring. On the other hand, if your melody contains only big intervals, people will presume you were thoroughly drunk when you wrote it. *New to writing melodies? Use the Melody Checklist in our Songwriting & Producing PDF. Over your first chord, write a handful of notes that end with a big interval around beat 3. And that big melodic jump should go up, not down (a large descending interval contains only a fraction of the drama of that same interval ascending). Be sure to begin your melody on beat 1, as this will make the most impact, and as this section is the chorus, first impressions matter even more than usual. Use a combination of note values for interest. And remember, if you wanna emphasize a chord’s major (happy) or minor (sad) vibe, then play its 3rd in your melody above. Melody’s opening segment with large interval (highlighted) for drama

Step 3. The Fall

You’re now gonna finish your melody’s first phrase with “the fall”. This is an utterly brilliant technique that Glass Animals use in their melody. And, it makes for a deeply pleasing balance between the drama and the gentle ride down afterwards. Your last note is currently that high note around beat 3, so now you’re gonna write a smooth contour that flows back down to somewhere around where you began. All good melodies have phrasing (i.e. where the melody rests), regardless of whether they’re sung or played on an instrument. This is because the melody itself needs to breathe, not just the singer. These rests also break-up a melody into digestible bits (i.e. phrases), which makes it easier to remember. So, end your first phrase on a longer note, and have at least a 1/16 rest at the end of your first bar (i.e. beat 4a). You can have an 1/8 rest if you prefer, but nothing longer than that, otherwise you’ll lose the momentum. First bar completed with “the fall” (highlighted) Notice how we didn’t play the chord’s root (G) in our melody. That root will be played in the chords below, so you don’t need to play it unless you actually want to.

Step 4. Rhythmic Variation

Copy and paste your first phrase into bar two, and make sure to also start it on beat 1. Glass Animals use a great hack in their second phrase, which makes it familiar to the listeners while simultaneously freshening it up so it’s not boring. They achieve this by using rhythmic variation. Simple, but massively effective. By only changing a few note values, the phrase is both predictable and unpredictable. First phrase copied and pasted into bar two (highlighted) Repetition is vital if you wanna appeal to the masses. People love a melody they know. But, too much repetition will make a melody predictable. And as soon as it’s predictable, their attention will move to some other novelty in their environment; probably their phone (it’s a sad reality that music is competing with phones for people’s attention). So it’s essential to repeat your melody for it to get stuck in their heads, and rhythmic variation will prevent it from losing its novelty and appeal. Glass Animals change almost all their note values, but only slightly. Let your ear guide you into the Goldilocks Zone in this step, as too much change will make the phrase sound unfamiliar, while not enough change will make it sound predictable. Lastly, Glass Animals add one new note at the end of their phrase, so it actually finishes on the last beat of the bar. This new note is a 1/16, which is completely unexpected, so it adds to the novelty. We did this too, but you don’t have to. If you don’t, though, then extend your last note so it also finishes at the end of the bar. Second phrase with rhythmic variations (highlighted)

Step 5. The Climb