Discover Hemispherics

Hemispherics

Hemispherics

Author: Hemispherics

Subscribed: 3Played: 34Subscribe

Share

© 2026 Hemispherics

Description

Hemispherics, el podcast de Fisioterapia y Neurorrehabilitación, presentado por Javier Sánchez Aguilar. En este podcast podrán encontrar:

• Reseñas de libros de neurociencia, neurorrehabilitación, fisioterapia.

• Comentarios de revisiones y artículos científicos relacionados con la fisioterapia y la neurorrehabilitación.

• Visibilización de investigadores/as.

• Exposición de temas específicos detallados sobre fisioterapia y neurorrehabilitación.

• Entrevistas a fisioterapeutas y especialistas en neurorrehabilitación.

• Reseñas de libros de neurociencia, neurorrehabilitación, fisioterapia.

• Comentarios de revisiones y artículos científicos relacionados con la fisioterapia y la neurorrehabilitación.

• Visibilización de investigadores/as.

• Exposición de temas específicos detallados sobre fisioterapia y neurorrehabilitación.

• Entrevistas a fisioterapeutas y especialistas en neurorrehabilitación.

93 Episodes

Reverse

En este episodio abordo la farmacología en neurorrehabilitación del adulto desde una perspectiva clínica y realista, pensada especialmente para profesionales no médicos que conviven a diario con informes, pautas y nombres de fármacos sin disponer siempre de un marco claro para interpretarlos. Recorremos los principales medicamentos utilizados en patologías neurológicas frecuentes —ictus, lesión medular, esclerosis múltiple, enfermedad de Parkinson, ELA, distonías y traumatismo craneoencefálico— diferenciando entre tratamientos agudos, terapias modificadoras de la enfermedad y manejo farmacológico de secuelas. A lo largo del episodio explico de forma progresiva los mecanismos de acción, la base neurofisiológica y el estado actual de la evidencia, poniendo especial énfasis en qué fármacos realmente cambian el pronóstico y cuáles cumplen un papel fundamentalmente sintomático. El objetivo no es prescribir, sino entender mejor cómo la farmacología condiciona la recuperación, la participación en terapia y la toma de decisiones en neurorrehabilitación, con una mirada crítica y basada en la evidencia disponible.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Adams, M. M., & Hicks, A. L. (2005). Spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal cord, 43(10), 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101757 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15838527/).

2. AFFINITY Trial Collaboration (2020). Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional outcome after acute stroke (AFFINITY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. Neurology, 19(8), 651–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30207-6 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32702334/).

3. Angeli, C. A., Edgerton, V. R., Gerasimenko, Y. P., & Harkema, S. J. (2014). Altering spinal cord excitability enables voluntary movements after chronic complete paralysis in humans. Brain : a journal of neurology, 137(Pt 5), 1394–1409. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu038 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24713270/).

4. Bracken, M. B., Shepard, M. J., Collins, W. F., Holford, T. R., Young, W., Baskin, D. S., Eisenberg, H. M., Flamm, E., Leo-Summers, L., & Maroon, J. (1990). A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. The New England journal of medicine, 322(20), 1405–1411. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199005173222001 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2278545/).

5. Bracken, M. B., Shepard, M. J., Holford, T. R., Leo-Summers, L., Aldrich, E. F., Fazl, M., Fehlings, M., Herr, D. L., Hitchon, P. W., Marshall, L. F., Nockels, R. P., Pascale, V., Perot, P. L., Jr, Piepmeier, J., Sonntag, V. K., Wagner, F., Wilberger, J. E., Winn, H. R., & Young, W. (1997). Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the Third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Randomized Controlled Trial. National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. JAMA, 277(20), 1597–1604 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9168289/).

6. Cardenas, D. D., Ditunno, J. F., Graziani, V., McLain, A. B., Lammertse, D. P., Potter, P. J., Alexander, M. S., Cohen, R., & Blight, A. R. (2014). Two phase 3, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of fampridine-SR for treatment of spasticity in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal cord, 52(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.137 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24216616/).

7. Chollet, F., Tardy, J., Albucher, J. F., Thalamas, C., Berard, E., Lamy, C., Bejot, Y., Deltour, S., Jaillard, A., Niclot, P., Guillon, B., Moulin, T., Marque, P., Pariente, J., Arnaud, C., & Loubinoux, I. (2011). Fluoxetine for motor recovery after acute ischaemic stroke (FLAME): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. Neurology, 10(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70314-8 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21216670/).

8. Dávalos, A., Alvarez-Sabín, J., Castillo, J., Díez-Tejedor, E., Ferro, J., Martínez-Vila, E., Serena, J., Segura, T., Cruz, V. T., Masjuan, J., Cobo, E., Secades, J. J., & International Citicoline Trial on acUte Stroke (ICTUS) trial investigators (2012). Citicoline in the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke: an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled study (ICTUS trial). Lancet (London, England), 380(9839), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60813-7 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22691567/).

9. EFFECTS Trial Collaboration (2020). Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional recovery after acute stroke (EFFECTS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. Neurology, 19(8), 661–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30219-2 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32702335/).

10. Fehlings, M. G., Theodore, N., Harrop, J., Maurais, G., Kuntz, C., Shaffrey, C. I., Kwon, B. K., Chapman, J., Yee, A., Tighe, A., & McKerracher, L. (2011). A phase I/IIa clinical trial of a recombinant Rho protein antagonist in acute spinal cord injury. Journal of neurotrauma, 28(5), 787–796. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2011.1765 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21381984/).

11. FOCUS Trial Collaboration (2019). Effects of fluoxetine on functional outcomes after acute stroke (FOCUS): a pragmatic, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 393(10168), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32823-X (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30528472/).

12. Forgione, N., & Fehlings, M. G. (2014). Rho-ROCK inhibition in the treatment of spinal cord injury. World neurosurgery, 82(3-4), e535–e539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2013.01.009 (http://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23298675/).

13. Fournier, A. E., Takizawa, B. T., & Strittmatter, S. M. (2003). Rho kinase inhibition enhances axonal regeneration in the injured CNS. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 23(4), 1416–1423. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01416.2003 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12598630/).

14. Giacino, J. T., Whyte, J., Bagiella, E., Kalmar, K., Childs, N., Khademi, A., Eifert, B., Long, D., Katz, D. I., Cho, S., Yablon, S. A., Luther, M., Hammond, F. M., Nordenbo, A., Novak, P., Mercer, W., Maurer-Karattup, P., & Sherer, M. (2012). Placebo-controlled trial of amantadine for severe traumatic brain injury. The New England journal of medicine, 366(9), 819–826. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1102609 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22375973/).

15. Goodman, A. D., Brown, T. R., Krupp, L. B., Schapiro, R. T., Schwid, S. R., Cohen, R., Marinucci, L. N., Blight, A. R., & Fampridine MS-F203 Investigators (2009). Sustained-release oral fampridine in multiple sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 373(9665), 732–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60442-6 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19249634/).

16. Goodman, A. D., Brown, T. R., Edwards, K. R., Krupp, L. B., Schapiro, R. T., Cohen, R., Marinucci, L. N., Blight, A. R., & MSF204 Investigators (2010). A phase 3 trial of extended release oral dalfampridine in multiple sclerosis. Annals of neurology, 68(4), 494–502. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22240 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20976768/).

17. Hurlbert, R. J., Hadley, M. N., Walters, B. C., Aarabi, B., Dhall, S. S., Gelb, D. E., Rozzelle, C. J., Ryken, T. C., & Theodore, N. (2013). Pharmacological therapy for acute spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery, 72 Suppl 2, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e31827765c6 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23417182/).

18. Johnston, S. C., Amarenco, P., Denison, H., Evans, S. R., Himmelmann, A., James, S., Knutsson, M., Ladenvall, P., Molina, C. A., Wang, Y., & THALES Investigators (2020). Ticagrelor and Aspirin or Aspirin Alone in Acute Ischemic Stroke or TIA. The New England journal of medicine, 383(3), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1916870 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32668111/).

19. Kheder, A., & Nair, K. P. (2012). Spasticity: pathophysiology, evaluation and management. Practical neurology, 12(5), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1136/practneurol-2011-000155 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22976059/).

20. Kirkman, M. A., Day, J., Gehring, K., Zienius, K., Grosshans, D., Taphoorn, M., Li, J., & Brown, P. D. (2022). Interventions for preventing and ameliorating cognitive deficits in adults treated with cranial irradiation. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 11(11), CD011335. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011335.pub3 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36427235/).

21. Martinsson L, Hårdemark H, Eksborg S. Amphetamines for improving recovery after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;2007(1):CD002090. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002090.pub2. PMID: 17253474; PMCID: PMC12278358 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17253474/).

22. Miller, T. M., Cudkowicz, M. E., Genge, A., Shaw, P. J., Sobue, G., Bucelli, R. C., Chiò, A., Van Damme, P., Ludolph, A. C., Glass, J. D., Andrews, J. A., Babu, S., Benatar, M., McDermott, C. J., Cochrane, T., Chary, S., Chew, S., Zhu, H., Wu, F., Nestorov, I., … VALOR and OLE Working Group (2022). Trial of Antisense Oligonucleotide Tofersen for SOD1 ALS. The New England journal of medicine, 387(12), 1099–1110. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2204705 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36129998/).

23. Mueller, B. K., Mack, H., & Teusch, N. (2005). Rho kinase, a promising drug target for neurological disorders. Nature reviews. Drug discovery, 4(5), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1719 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15864268/).

24. Nourbakhsh, B., Revirajan, N., & Waubant, E. (2018). Treatment of fatigue with methylphenidate, modafinil and amantadine in multiple sclerosis (TRIUMPHANT-MS): Study design for a pragmatic, randomized, double-blind, crossover clinical trial. Contemporary clinical trials, 64, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2017.11.005 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.

En este episodio converso con Aitor Martín Odriozola, fisioterapeuta, doctor en neurociencias y Responsable de Aplicaciones Clínicas en Fesia Technology, para hablar en profundidad sobre la estimulación eléctrica funcional (FES) y su uso en neurorrehabilitación.

A lo largo de la entrevista recorremos su trayectoria profesional, desde la fisioterapia clínica hasta su papel actual coordinando formación, investigación y ensayos clínicos, y abordamos uno de los grandes problemas del campo: la confusión conceptual y terminológica en torno a la estimulación eléctrica. Hablamos de qué es realmente la FES, qué no lo es, por qué el ancho de pulso importa más de lo que parece, y cuáles son los límites reales de la estimulación en casos como la denervación periférica.

También reflexionamos sobre la transición entre dispositivos terapéuticos y asistivos, la necesidad de medir impacto funcional más allá de la contracción muscular, y la resistencia cultural que todavía existe en España hacia la tecnología asistiva. Desde su experiencia internacional, Aitor aporta una visión clara sobre cómo se está utilizando la FES en otros países y qué podemos aprender de ello.

Finalmente, hablamos del papel de International Functional Electrical Stimulation Society (IFESS) como espacio de conexión y divulgación basada en evidencia, y cerramos con una conversación más personal sobre organización, viajes, empresa y cómo mantener criterio y calma en un sector cada vez más complejo.

Un episodio para entender la estimulación eléctrica con profundidad, lejos de modas, protocolos vacíos y promesas exageradas.

Referencias del episodio:

- Bear, M. F., Connors, B. W., & Paradiso, M. A. Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. Wolters Kluwer.

- Crossman, A. R., & Neary, D. Neuroanatomía. Elsevier.

- Watson, T. (ed.). Electroterapia basada en la evidencia. Elsevier.

- Shick, T. Functional Electrical Stimulation in Neurorehabilitation. Springer.

- Functional Electrical Stimulation and neurorehabilitation outcomes. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41257457/

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Functional electrical stimulation for neurological rehabilitation. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD015338.pub2/full

- Electroterapia en Fisioterapia. Editorial Médica Panamericana.

- Elsevier – ScienceDirect (Book Chapter). Electrical stimulation in neurorehabilitation. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/edited-volume/abs/pii/B9780128198773000056

- Guyton, A. C., & Hall, J. E. Tratado de fisiología médica. Elsevier.

- Jameson, J. L. et al. Harrison. Principios de Medicina Interna. McGraw-Hill.

¿Puede existir la mente cuando el cerebro apenas está ahí? En este episodio de Hemispherics exploramos casos clínicos extremos —hidrocefalias masivas, hemisferectomías, microcefalia— y estados límite de conciencia como la lucidez terminal, la conciencia bajo anestesia o las experiencias cercanas a la muerte. Historias reales, bien documentadas, que desafían la idea simplista de que “la mente es solo el cerebro”.

No para abrazar lo místico, sino para ampliar el marco: plasticidad extrema, redes alternativas, conciencia distribuida y los límites reales de lo que hoy sabemos. Un viaje a los bordes de la neurociencia, donde las respuestas no son claras… pero las preguntas son fascinantes.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Asaridou, S. S., Demir-Lira, Ö. E., Goldin-Meadow, S., Levine, S. C., & Small, S. L. (2020). Language development and brain reorganization in a child born without the left hemisphere. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior, 127, 290–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2020.02.006 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32259667/).

2. Feuillet, L., Dufour, H., & Pelletier, J. (2007). Brain of a white-collar worker. Lancet (London, England), 370(9583), 262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61127-1 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17658396/).

3. Green, A. J., Yates, J. R., Taylor, A. M., Biggs, P., McGuire, G. M., McConville, C. M., Billing, C. J., & Barnes, N. D. (1995). Severe microcephaly with normal intellectual development: the Nijmegen breakage syndrome. Archives of disease in childhood, 73(5), 431–434. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.73.5.431 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8554361/).

4. Kofman, K., & Levin, M. (2025). Cases of unconventional information flow across the mind-body interface. Mind and Matter, 23(1), Article 13. https://doi.org/10.5376/mm2025.13 (https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/imp/mm/2025/00000023/00000001/art00003).

5. Lewin R. (1980). Is your brain really necessary?. Science (New York, N.Y.), 210(4475), 1232–1234. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7434023 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7434023/).

6. Merker B. (2007). Consciousness without a cerebral cortex: a challenge for neuroscience and medicine. The Behavioral and brain sciences, 30(1), 63–134. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07000891 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17475053/).

7. Parnia, S., Spearpoint, K., de Vos, G., Fenwick, P., Goldberg, D., Yang, J., Zhu, J., Baker, K., Killingback, H., McLean, P., Wood, M., Zafari, A. M., Dickert, N., Beisteiner, R., Sterz, F., Berger, M., Warlow, C., Bullock, S., Lovett, S., McPara, R. M., … Schoenfeld, E. R. (2014). AWARE-AWAreness during REsuscitation-a prospective study. Resuscitation, 85(12), 1799–1805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.09.004 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25301715/).

8. Parnia, S., Keshavarz Shirazi, T., Patel, J., Tran, L., Sinha, N., O'Neill, C., Roellke, E., Mengotto, A., Findlay, S., McBrine, M., Spiegel, R., Tarpey, T., Huppert, E., Jaffe, I., Gonzales, A. M., Xu, J., Koopman, E., Perkins, G. D., Vuylsteke, A., Bloom, B. M., … Deakin, C. D. (2023). AWAreness during REsuscitation - II: A multi-center study of consciousness and awareness in cardiac arrest. Resuscitation, 191, 109903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.109903 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37423492/).

9. Ross, J. P., Post, S. G., & Scheinfeld, L. (2024). Lucidity in the Deeply Forgetful: A Scoping Review. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD, 98(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-231396 (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10977389/).

10. Sandhu, K., & Dash, H. (2009). Awareness during anaesthesia. Indian journal of anaesthesia, 53(2), 148–157 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20640115/).

11. Teresi, J. A., Ramirez, M., Ellis, J., Tan, A., Capezuti, E., Silver, S., Boratgis, G., Eimicke, J. P., Gonzalez-Lopez, P., Devanand, D. P., & Luchsinger, J. A. (2023). Reports About Paradoxical Lucidity from Health Care Professionals: A Pilot Study. Journal of gerontological nursing, 49(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20221206-03 (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11100277/).

12. Timmermann, C., Roseman, L., Williams, L., Erritzoe, D., Martial, C., Cassol, H., Laureys, S., Nutt, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2018). DMT Models the Near-Death Experience. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 1424. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01424 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30174629/).

En este episodio viajamos desde los orígenes más controvertidos de la Neurociencia moderna —los monos de Silver Spring— hasta la consolidación del protocolo oficial de la Constraint-Induced Therapy (CIMT) de Taub y Morris en la Universidad de Alabama. Repasamos cómo surgió el concepto de learned non-use, cómo se formalizó la terapia, por qué el Paquete de Transferencia fue una revolución conductual, y qué nos dice la evidencia más robusta (incluyendo el EXCITE trial, Premio PEDro al mejor ensayo clínico del año).

También exploramos la evolución del protocolo, desde las 6 horas diarias iniciales hasta el formato actual de 3.5h/día, y cómo el equipo brasileño de Sarah Dos Anjos logró expandir la CIMT al miembro inferior con resultados positivos. Cerramos con una revisión profunda del papel del MAL, del protocolo KEYS y de la extended CIMT para manos pléjicas.

Un episodio imprescindible para cualquier profesional que trate a personas con ictus o quiera comprender cómo una intervención conductual intensiva puede modificar el uso real del brazo afecto… y el cerebro.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Corbetta, D., Sirtori, V., Castellini, G., Moja, L., & Gatti, R. (2015). Constraint-induced movement therapy for upper extremities in people with stroke. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2015(10), CD004433. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004433.pub3 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26446577/).

2. Dos Anjos, S. M., Morris, D. M., & Taub, E. (2020). Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy for Improving Motor Function of the Paretic Lower Extremity After Stroke. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 99(6), e75–e78. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000001249 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31246610/).

3. Dos Anjos, S., Morris, D., & Taub, E. (2020). Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy for Lower Extremity Function: Describing the LE-CIMT Protocol. Physical therapy, 100(4), 698–707. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzz191 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31899495/).

4. Dos Anjos, S., Bowman, M., & Morris, D. (2025). Effects of a Distributed Form of Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy for Clinical Application: The Keys Treatment Protocol. Brain sciences, 15(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15010087 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39851454/).

5. Gauthier, L. V., Taub, E., Perkins, C., Ortmann, M., Mark, V. W., & Uswatte, G. (2008). Remodeling the brain: plastic structural brain changes produced by different motor therapies after stroke. Stroke, 39(5), 1520–1525. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.502229 (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2574634/).

6. Hakkennes, S., & Keating, J. L. (2005). Constraint-induced movement therapy following stroke: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. The Australian journal of physiotherapy, 51(4), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0004-9514(05)70003-9 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16321129/).

7. Morris, D. M., Taub, E., & Mark, V. W. (2006). Constraint-induced movement therapy: characterizing the intervention protocol. Europa medicophysica, 42(3), 257–268 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17039224/).

8. Richards, L., Gonzalez Rothi, L. J., Davis, S., Wu, S. S., & Nadeau, S. E. (2006). Limited dose response to constraint-induced movement therapy in patients with chronic stroke. Clinical rehabilitation, 20(12), 1066–1074. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215506071263 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17148518/).

9. Sterr, A., Elbert, T., Berthold, I., Kölbel, S., Rockstroh, B., & Taub, E. (2002). Longer versus shorter daily constraint-induced movement therapy of chronic hemiparesis: an exploratory study. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 83(10), 1374–1377. https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2002.35108 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12370871/).

10. Taub, E., Miller, N. E., Novack, T. A., Cook, E. W., 3rd, Fleming, W. C., Nepomuceno, C. S., Connell, J. S., & Crago, J. E. (1993). Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 74(4), 347–354 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8466415/).

11. Taub, E., Uswatte, G., & Pidikiti, R. (1999). Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy: a new family of techniques with broad application to physical rehabilitation--a clinical review. Journal of rehabilitation research and development, 36(3), 237–251 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10659807/).

12. Taub, E., & Morris, D. M. (2001). Constraint-induced movement therapy to enhance recovery after stroke. Current atherosclerosis reports, 3(4), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-001-0020-0 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11389792/).

13. Taub, E., Uswatte, G., Mark, V. W., Morris, D. M., Barman, J., Bowman, M. H., Bryson, C., Delgado, A., & Bishop-McKay, S. (2013). Method for enhancing real-world use of a more affected arm in chronic stroke: transfer package of constraint-induced movement therapy. Stroke, 44(5), 1383–1388. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000559 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23520237/).

14. Uswatte, G., Taub, E., Morris, D., Barman, J., & Crago, J. (2006). Contribution of the shaping and restraint components of Constraint-Induced Movement therapy to treatment outcome. NeuroRehabilitation, 21(2), 147–156 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16917161/).

15. Uswatte, G., Taub, E., Bowman, M. H., Delgado, A., Bryson, C., Morris, D. M., Mckay, S., Barman, J., & Mark, V. W. (2018). Rehabilitation of stroke patients with plegic hands: Randomized controlled trial of expanded Constraint-Induced Movement therapy. Restorative neurology and neuroscience, 36(2), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.3233/RNN-170792 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29526860/).

16. Wolf, S. L., Lecraw, D. E., Barton, L. A., & Jann, B. B. (1989). Forced use of hemiplegic upper extremities to reverse the effect of learned nonuse among chronic stroke and head-injured patients. Experimental neurology, 104(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-4886(89)80005-6 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2707361/).

17. Wolf, S. L., Winstein, C. J., Miller, J. P., Taub, E., Uswatte, G., Morris, D., Giuliani, C., Light, K. E., Nichols-Larsen, D., & EXCITE Investigators (2006). Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke: the EXCITE randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 296(17), 2095–2104. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.17.2095 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17077374/).

En este episodio, exploramos un fenómeno cada vez más inquietante en las consultas y unidades de neurología: el aumento del ictus en adultos jóvenes. A partir de la evidencia más reciente, analizamos cómo los factores de riesgo clásicos están dando paso a nuevos protagonistas del siglo XXI, entre ellos el estrés crónico. Revisamos el papel del ictus criptogénico, las causas vasculares menos conocidas y los mecanismos por los cuales la sobrecarga emocional, laboral o social puede alterar la fisiología cerebrovascular hasta precipitar un evento agudo. También abordamos la diferencia de impacto entre hombres y mujeres, los hallazgos de estudios internacionales como INTERSTROKE y ERICH, y cómo la gestión del estrés debería considerarse una estrategia real de prevención neurológica. Un episodio para reflexionar sobre la relación entre mente, sociedad y cerebro en una generación que vive —y enferma— bajo presión.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Behymer, T. P., Sekar, P., Demel, S. L., Aziz, Y. N., Coleman, E. R., Williamson, B. J., Stanton, R. J., Sawyer, R. P., Turner, A. C., Vagal, V. S., Osborne, J., Gilkerson, L. A., Comeau, M. E., Flaherty, M. L., Langefeld, C. D., & Woo, D. (2025). Psychosocial Stress and Risk for Intracerebral Hemorrhage in the ERICH (Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage) Study. Journal of the American Heart Association, 14(6), e024457. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.024457 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40055853/).

2. Egido, J. A., Castillo, O., Roig, B., Sanz, I., Herrero, M. R., Garay, M. T., Garcia, A. M., Fuentes, M., & Fernandez, C. (2012). Is psycho-physical stress a risk factor for stroke? A case-control study. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 83(11), 1104–1110. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-302420 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22930814/).

3. Gutiérrez-Zúñiga, R., Fuentes, B., & Díez-Tejedor, E. (2018). Ictus criptogénico. Un no diagnóstico. Medicina Clínica, 151 (3), 116-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2018.01.024 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0025775318300770).

4. Khan, M., Wasay, M., O'Donnell, M. J., Iqbal, R., Langhorne, P., Rosengren, A., Damasceno, A., Oguz, A., Lanas, F., Pogosova, N., Alhussain, F., Oveisgharan, S., Czlonkowska, A., Ryglewicz, D., & Yusuf, S. (2023). Risk Factors for Stroke in the Young (18-45 Years): A Case-Control Analysis of INTERSTROKE Data from 32 Countries. Neuroepidemiology, 57(5), 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1159/000530675 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37231971/).

5. Kutal, S., Tulkki, L. J., Sarkanen, T., Redfors, P., Jood, K., Nordanstig, A., Yeşilot, N., Sezgin, M., Ylikotila, P., Zedde, M., Junttola, U., Fromm, A., Ryliskiene, K., Licenik, R., Ferdinand, P., Jatužis, D., Kõrv, L., Kõrv, J., Pezzini, A., Sinisalo, J., … Martinez-Majander, N. (2025). Association Between Self-Perceived Stress and Cryptogenic Ischemic Stroke in Young Adults: A Case-Control Study. Neurology, 104(6), e213369. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000213369 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40043226/).

6. Li, W., Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., Shentu, W., Yan, S., Chen, Q., Qiao, S., & Kong, Q. (2025). Clinical research progress on pathogenesis and treatment of Patent Foramen Ovale-associated stroke. Frontiers in neurology, 16, 1512399. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2025.1512399 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40291846/).

7. Smyth, A., O'Donnell, M., Hankey, G. J., Rangarajan, S., Lopez-Jaramillo, P., Xavier, D., Zhang, H., Canavan, M., Damasceno, A., Langhorne, P., Avezum, A., Pogosova, N., Oguz, A., Yusuf, S., & INTERSTROKE investigators (2022). Anger or emotional upset and heavy physical exertion as triggers of stroke: the INTERSTROKE study. European heart journal, 43(3), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab738 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34850877/).

8. Verhoeven, J. I., Fan, B., Broeders, M. J. M., Driessen, C. M. L., Vaartjes, I. C. H., Klijn, C. J. M., & de Leeuw, F. E. (2023). Association of Stroke at Young Age With New Cancer in the Years After Stroke Among Patients in the Netherlands. JAMA network open, 6(3), e235002. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.5002 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36976557/).

9. Wegener S. (2022). Triggers of stroke: anger, emotional upset, and heavy physical exertion. New insights from the INTERSTROKE study. European heart journal, 43(3), 210–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab755 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34850880/).

10. Yaghi, S., Bernstein, R. A., Passman, R., Okin, P. M., & Furie, K. L. (2017). Cryptogenic Stroke: Research and Practice. Circulation research, 120(3), 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308447 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28154102/).

11. Yang, D., & Elkind, M. S. V. (2023). Current perspectives on the clinical management of cryptogenic stroke. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 23(3), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2023.2192403 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36934333/).

En este episodio converso con la Dra. Laura Mena García, optometrista e investigadora del Instituto de Oftalmobiología Aplicada (IOBA) de la Universidad de Valladolid. Su trabajo ha contribuido al desarrollo de nuevos programas de neurorrehabilitación visual para pacientes con hemianopsia y otros déficits campimétricos derivados del daño cerebral adquirido.

Hablamos sobre cómo el cerebro procesa la información visual más allá del lóbulo occipital, los mecanismos anatómicos y funcionales que explican las hemianopsias, y las diferencias con otros trastornos como la heminegligencia. La Dra. Mena expone con claridad los fundamentos y la evidencia actual de las terapias compensatorias, restitutivas y sustitutivas, y comparte su experiencia clínica en el diseño de programas de rehabilitación visual basados en el reentrenamiento de los movimientos oculares y la atención visual.

Una conversación que abre un campo poco explorado en la neurorrehabilitación: la visión desde una perspectiva cerebral. Recomendable ver el episodio en YouTube para ver diapositivas e imágenes que hacen alusión a la entrevista y que aportan mucho.

Referencias de interés:

1) Mena-Garcia, L., Pastor-Jimeno, J. C., Maldonado, M. J., Coco-Martin, M. B., Fernandez, I., & Arenillas, J. F. (2021). Multitasking Compensatory Saccadic Training Program for Hemianopia Patients: A New Approach With 3-Dimensional Real-World Objects. Translational vision science & technology, 10(2), 3. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.10.2.3 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34003888/).

2) Mena-Garcia, L., Maldonado-Lopez, M. J., Fernandez, I., Coco-Martin, M. B., Finat-Saez, J., Martinez-Jimenez, J. L., Pastor-Jimeno, J. C., & Arenillas, J. F. (2020). Visual processing speed in hemianopia patients secondary to acquired brain injury: a new assessment methodology. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation, 17(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-020-0650-5 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32005265/).

3) Felleman, D. J., & Van Essen, D. C. (1991). Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 1(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/1.1.1-a (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1822724/).

4) Macaluso, E., Frith, C. D., & Driver, J. (2007). Delay activity and sensory-motor translation during planned eye or hand movements to visual or tactile targets. Journal of neurophysiology, 98(5), 3081–3094. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00192.2007 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17898151/).

5) Pollock, A., Hazelton, C., Rowe, F. J., Jonuscheit, S., Kernohan, A., Angilley, J., Henderson, C. A., Langhorne, P., & Campbell, P. (2019). Interventions for visual field defects in people with stroke. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 5(5), CD008388. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008388.pub3 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31120142/).

6) Postuma, E. M. J. L., Heutink, J., Tol, S., Jansen, J. L., Koopman, J., Cornelissen, F. W., & de Haan, G. A. (2024). A systematic review on visual scanning behaviour in hemianopia considering task specificity, performance improvement, spontaneous and training-induced adaptations. Disability and rehabilitation, 46(15), 3221–3242. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2023.2243590 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37563867/).

7) IOBA: https://www.ioba.es/ LinkedIN: https://www.linkedin.com/company/iobauva/posts/?feedView=all

¿Qué hacemos cuando el brazo no se mueve? En este episodio hablamos de ese punto de partida que tanto intimida: el miembro superior completamente pléjico tras un ictus. A partir de la experiencia clínica y la neurofisiología más actual, exploramos cómo comenzar a activar un brazo desde cero. Abordamos estrategias basadas en evidencia como el trabajo en carga en cadena cinética cerrada, la electroestimulación funcional multicanal, el uso de herramientas como el PANAt Laptool, el entrenamiento bilateral y los paradigmas de uso forzado inspirados en Forced-Use Utley/Woll. También repasamos el papel del entrenamiento con soporte de peso, ese enfoque nacido de los laboratorios de Dewald y Ellis que ha cambiado la forma de entender la sinergia flexora.

Un episodio para fisioterapeutas y terapeutas ocupacionales que quieren comprender no solo qué hacer, sino por qué hacerlo.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Arya, K. N., & Pandian, S. (2014). Interlimb neural coupling: implications for poststroke hemiparesis. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine, 57(9-10), 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2014.06.003 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25262645/).

2. Cauraugh, J. H., & Summers, J. J. (2005). Neural plasticity and bilateral movements: A rehabilitation approach for chronic stroke. Progress in neurobiology, 75(5), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.001 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15885874/).

3. Chen, S., Qiu, Y., Bassile, C. C., Lee, A., Chen, R., & Xu, D. (2022). Effectiveness and Success Factors of Bilateral Arm Training After Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 14, 875794. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.875794 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35547621/).

4. Ellis, M. D., Carmona, C., Drogos, J., & Dewald, J. P. A. (2018). Progressive Abduction Loading Therapy with Horizontal-Plane Viscous Resistance Targeting Weakness and Flexion Synergy to Treat Upper Limb Function in Chronic Hemiparetic Stroke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Frontiers in neurology, 9, 71. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00071 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29515514/)

5. Jang, S. H., & Lee, S. J. (2019). Corticoreticular Tract in the Human Brain: A Mini Review. Frontiers in neurology, 10, 1188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01188 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31803130/).

6. Khan, M. A., Fares, H., Ghayvat, H., Brunner, I. C., Puthusserypady, S., Razavi, B., Lansberg, M., Poon, A., & Meador, K. J. (2023). A systematic review on functional electrical stimulation based rehabilitation systems for upper limb post-stroke recovery. Frontiers in neurology, 14, 1272992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1272992 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38145118/).

7. Langhorne, P., Wu, O., Rodgers, H., Ashburn, A., & Bernhardt, J. (2017). A Very Early Rehabilitation Trial after stroke (AVERT): a Phase III, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England), 21(54), 1–120. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta21540 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28967376/).

8. Michielsen, M., Cornelis, L., Cruycke, L., De Smedt, A., Fobelets, M., Putman, K., Vander Plaetse, M., Verheyden, G., & Meyer, S. (2025). Arm-hand BOOST (AHA-BOOST) therapy to improve recovery of the upper limb after stroke: rationale and description by means of the TIDieR checklist. Frontiers in neurology, 16, 1599762. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2025.1599762 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41001199/).

9. Schick, T., Kolm, D., Leitner, A., Schober, S., Steinmetz, M., & Fheodoroff, K. (2022). Efficacy of Four-Channel Functional Electrical Stimulation on Moderate Arm Paresis in Subacute Stroke Patients-Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 10(4), 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040704 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35455881/).

10. Sukal, T. M., Ellis, M. D., & Dewald, J. P. (2007). Shoulder abduction-induced reductions in reaching work area following hemiparetic stroke: neuroscientific implications. Experimental brain research, 183(2), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-007-1029-6 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17634933/)

11. Whitall, J., McCombe Waller, S., Silver, K. H., & Macko, R. F. (2000). Repetitive bilateral arm training with rhythmic auditory cueing improves motor function in chronic hemiparetic stroke. Stroke, 31(10), 2390–2395. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.31.10.2390 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11022069/).

En este episodio nos adentramos en una técnica emergente que está ganando terreno en el tratamiento de la espasticidad: la crioneurolisis. Hablamos con el Dr. José Alexandre Pereira, uno de los referentes europeos en la aplicación clínica de esta intervención mínimamente invasiva, que utiliza frío extremo para bloquear de forma selectiva nervios periféricos y reducir el tono muscular patológico.

Exploramos el origen histórico de la técnica, su reaparición en el ámbito rehabilitador, sus fundamentos neurofisiológicos, las indicaciones clínicas más comunes, y cómo se compara con otras estrategias como la toxina botulínica. También hablamos sobre los estudios en curso para seguir aumentando la evidencia científica.

Un episodio técnico, pero profundamente clínico, donde la fisiología, la ecografía y la toma de decisiones terapéuticas se encuentran con la innovación.

Podéis seguir al Dr. Pereira en LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/dr-jose-pereira-physical-medicine-and-rehabilitation/

Referencias del episodio:

1) Li, S., Winston, P., & Mas, M. F. (2024). Spasticity Treatment Beyond Botulinum Toxins. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America, 35(2), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2023.06.009 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38514226/).

2) Rubenstein, J., Harvey, A. W., Vincent, D., & Winston, P. (2021). Cryoneurotomy to Reduce Spasticity and Improve Range of Motion in Spastic Flexed Elbow: A Visual Vignette. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 100(5), e65. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000001624 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33105153/).

3) Winston, P., & Vincent, D. (2024). Cryoneurolysis as a Novel Treatment for Spasticity, Associated Pain and Presumed Contracture. Advances in rehabilitation science and practice, 13, 27536351241285198. https://doi.org/10.1177/27536351241285198 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39377080/).

4) Winston, P., MacRae, F., Rajapakshe, S., Morrissey, I., Boissonnault, È., Vincent, D., & Hashemi, M. (2023). Analysis of Adverse Effects of Cryoneurolysis for the Treatment of Spasticity. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 102(11), 1008–1013. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000002267 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37104641/).

En este episodio exploramos a fondo el mutismo acinético, una de las manifestaciones más desconcertantes tras un daño cerebral grave. Hablamos de su base neurofisiológica, su relación con el sistema dopaminérgico y los circuitos prefronto-subcorticales, y cómo se diferencia clínicamente de otros estados de conciencia alterada. Recorremos también las opciones terapéuticas más prometedoras, desde la estimulación multisensorial y la verticalización robótica hasta técnicas de neuromodulación como la estimulación cerebral profunda, la estimulación medular o la tDCS. Un episodio técnico, narrativo y lleno de preguntas clínicas clave, pensado para quienes trabajan día a día con pacientes que aún no responden... pero que podrían hacerlo.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Arnts, H., van Erp, W. S., Lavrijsen, J. C. M., van Gaal, S., Groenewegen, H. J., & van den Munckhof, P. (2020). On the pathophysiology and treatment of akinetic mutism. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 112, 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.02.006 8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32044373/).

2. Arnts, H., Tewarie, P., van Erp, W. S., Overbeek, B. U., Stam, C. J., Lavrijsen, J. C. M., Booij, J., Vandertop, W. P., Schuurman, R., Hillebrand, A., & van den Munckhof, P. (2022). Clinical and neurophysiological effects of central thalamic deep brain stimulation in the minimally conscious state after severe brain injury. Scientific reports, 12(1), 12932. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16470-2 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35902627/).

3. Arnts, H., Tewarie, P., van Erp, W., Schuurman, R., Boon, L. I., Pennartz, C. M. A., Stam, C. J., Hillebrand, A., & van den Munckhof, P. (2024). Deep brain stimulation of the central thalamus restores arousal and motivation in a zolpidem-responsive patient with akinetic mutism after severe brain injury. Scientific reports, 14(1), 2950. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52267-1 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38316863/).

4. Bai, Y., Xia, X., Li, X., Wang, Y., Yang, Y., Liu, Y., Liang, Z., & He, J. (2017). Spinal cord stimulation modulates frontal delta and gamma in patients of minimally consciousness state. Neuroscience, 346, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.01.036 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28147246/).

5. Bai, Y., Xia, X., Liang, Z., Wang, Y., Yang, Y., He, J., & Li, X. (2017). Corrigendum: Frontal Connectivity in EEG Gamma (30-45 Hz) Respond to Spinal Cord Stimulation in Minimally Conscious State Patients. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 11, 251. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2017.00251 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28828002/).

6. Bai, Y., Lin, Y., & Ziemann, U. (2021). Managing disorders of consciousness: the role of electroencephalography. Journal of neurology, 268(11), 4033–4065. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10095-z (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32915309/).

7. Cairns, H., Oldfield, R. C., Pennybacker, J. B., & Whitteridge, D. (1941). Akinetic mutism with an epidermoid cyst of the 3rd ventricle. Brain, 64(4), 273–290 (https://academic.oup.com/brain/article-abstract/64/4/273/332088?redirectedFrom=fulltext).

8. Chen, Q., Huang, W., Tang, J., Ye, G., Meng, H., Jiang, Q., Ge, L., Li, H., Liu, L., Jiang, Q., & Wang, D. (2025). Reviving consciousness: The impact of short-term spinal cord stimulation on patients with early-onset prolonged disorders of consciousness. Journal of Neurorestoratology, 13(1), 100143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnrt.2024.100143 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2324242624000500?via%3Dihub).

9. Clavo, B., Robaina, F., Montz, R., Carames, M. A., Otermin, E., & Carreras, J. L. (2008). Effect of cervical spinal cord stimulation on cerebral glucose metabolism. Neurological research, 30(6), 652–654. https://doi.org/10.1179/174313208X305373 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18513465/).

10. Corazzol, M., Lio, G., Lefevre, A., Deiana, G., Tell, L., André-Obadia, N., Bourdillon, P., Guenot, M., Desmurget, M., Luauté, J., & Sirigu, A. (2017). Restoring consciousness with vagus nerve stimulation. Current biology : CB, 27(18), R994–R996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.07.060 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28950091/).

11. Della Pepa, G. M., Fukaya, C., La Rocca, G., Zhong, J., & Visocchi, M. (2013). Neuromodulation of vegetative state through spinal cord stimulation: where are we now and where are we going?. Stereotactic and functional neurosurgery, 91(5), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348271 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23797266/).

12. De Luca, R., Bonanno, M., Vermiglio, G., Trombetta, G., Andidero, E., Caminiti, A., Pollicino, P., Rifici, C., & Calabrò, R. S. (2022). Robotic Verticalization plus Music Therapy in Chronic Disorders of Consciousness: Promising Results from a Pilot Study. Brain sciences, 12(8), 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12081045 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36009107/).

13. Dong, X., Tang, Y., Zhou, Y., & Feng, Z. (2023). Stimulation of vagus nerve for patients with disorders of consciousness: a systematic review. Frontiers in neuroscience, 17, 1257378. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1257378 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37781261/).

14. Fan, W., Fan, Y., Liao, Z., & Yin, Y. (2023). Effect of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Patients With Disorders of Consciousness: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 102(12), 1102–1110. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000002290 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37205736/).

15. Frazzitta, G., Zivi, I., Valsecchi, R., Bonini, S., Maffia, S., Molatore, K., Sebastianelli, L., Zarucchi, A., Matteri, D., Ercoli, G., Maestri, R., & Saltuari, L. (2016). Effectiveness of a Very Early Stepping Verticalization Protocol in Severe Acquired Brain Injured Patients: A Randomized Pilot Study in ICU. PloS one, 11(7), e0158030. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158030 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27447483/).

16. Jang, S. H., & Byun, D. H. (2022). A Review of Studies on the Role of Diffusion Tensor Magnetic Resonance Imaging Tractography in the Evaluation of the Fronto-Subcortical Circuit in Patients with Akinetic Mutism. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research, 28, e936251. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.936251 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35181647/).

17. Lombardi, F., Taricco, M., De Tanti, A., Telaro, E., & Liberati, A. (2002). Sensory stimulation for brain injured individuals in coma or vegetative state. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2002(2), CD001427. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001427 (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7045727/).

18. Magee, W. L., & O'Kelly, J. (2015). Music therapy with disorders of consciousness: current evidence and emergent evidence-based practice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1337, 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12633 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25773642/).

19. Mateo-Sierra, O., Gutiérrez, F.A., Fernández-Carballal, C., Pinilla, D., Mosqueira, B., Iza, B., & Carrillo, R.. (2005). Mutismo acinético relacionado con hidrocefalia y cirugía cerebelosa tratado con bromocriptina y efedrina: revisión fisiopatológica. Neurocirugía, 16(2), 134-141. (https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1130-14732005000200005).

20. Noé, E., Ferri, J., Colomer, C., Moliner, B., O'Valle, M., Ugart, P., Rodriguez, C., & Llorens, R. (2020). Feasibility, safety and efficacy of transauricular vagus nerve stimulation in a cohort of patients with disorders of consciousness. Brain stimulation, 13(2), 427–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2019.12.005 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31866491/).

21. Norwood, M. F., Lakhani, A., Watling, D. P., Marsh, C. H., & Zeeman, H. (2023). Efficacy of Multimodal Sensory Therapy in Adult Acquired Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Neuropsychology review, 33(4), 693–713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-022-09560-5 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36056243/).

22. O'Neal, C. M., Schroeder, L. N., Wells, A. A., Chen, S., Stephens, T. M., Glenn, C. A., & Conner, A. K. (2021). Patient Outcomes in Disorders of Consciousness Following Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. Frontiers in neurology, 12, 694970. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.694970 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34475848/).

23. Schiff, N. D., Giacino, J. T., Kalmar, K., Victor, J. D., Baker, K., Gerber, M., Fritz, B., Eisenberg, B., Biondi, T., O'Connor, J., Kobylarz, E. J., Farris, S., Machado, A., McCagg, C., Plum, F., Fins, J. J., & Rezai, A. R. (2007). Behavioural improvements with thalamic stimulation after severe traumatic brain injury. Nature, 448(7153), 600–603. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06041 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17671503/).

24. Schiff N. D. (2016). Central thalamic deep brain stimulation to support anterior forebrain mesocircuit function in the severely injured brain. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996), 123(7), 797–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-016-1547-0 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27113938/).

25. Schiff N. D. (2023). Mesocircuit mechanisms in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of consciousness. Presse medicale (Paris, France : 1983), 52(2), 104161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2022.104161 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36563999/).

26. Shimojo, S., & Shams, L. (2001). Sensory modalities are not separate modalities: plasticity and interactions. Current opinion in neurobiology, 11(4), 505–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00241-5 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11502399/).

27. Stephens, T. M., Young, I. M., O'Neal, C. M., Dadario, N. B., Briggs, R. G., Teo, C., & Sughrue, M. E. (2021). Akinetic mutism reversed by inferior parietal lobule repetitive theta burst stimulation: Can we restore default mode network function for therapeutic benefit?. Brain and behavior, 11(8), e02180. h

En este episodio exploramos las diversas formas en que se ha conceptualizado el funcionamiento del cerebro humano, guiados por las fascinantes metáforas divulgadas por el neuropsicólogo Javier Tirapu Ustárroz: el cerebro darwiniano (instinto y evolución), el skinneriano (aprendizaje por refuerzo), el popperiano (simulación mental y predicción), y el gregoriano (empatía y simulación social).

Profundizamos luego en la controvertida hipótesis del "cerebro bayesiano", según la cual nuestro cerebro actuaría como un científico estadístico que actualiza constantemente sus creencias sobre el mundo combinando experiencias previas y nueva información sensorial. Apoyándonos en el provocador artículo de Madhur Mangalam, "The Myth of the Bayesian Brain" (2025), examinamos en profundidad las fortalezas y las debilidades de este paradigma tan influyente.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Mangalam M. (2025). The myth of the Bayesian brain. European journal of applied physiology, 10.1007/s00421-025-05855-6. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-025-05855-6 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40569419/).

2. Tirapu Ustárroz, J. (2008). ¿Para qué sirve el cerebro? Manual para principiantes. Editorial Alianza (https://www.calameo.com/books/00638959573c26c5b3fbc).

En este episodio nos adentramos en una dimensión tan esencial como olvidada de la recuperación neurológica: la sensibilidad. Exploramos con profundidad la neurofisiología de los sistemas sensoriales, los tipos de sensibilidad, las vías implicadas y los déficits somatosensoriales que pueden aparecer tras un ictus. Hablamos de evaluación clínica y neurofisiológica, de escalas, de estereognosia, de patrones exploratorios, y de la implicación cortical tras una lesión. Abordamos también las principales intervenciones terapéuticas, desde la estimulación eléctrica sensitiva (SAES) hasta el entrenamiento activo sensitivo, repasando la evidencia más actual y las claves para una rehabilitación sensitiva eficaz.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Bastos, V. S., Faria, C. D. C. M., Faria-Fortini, I., & Scianni, A. A. (2025). Prevalence of sensory impairments and its contribution to functional disability in individuals with acute stroke: A cross-sectional study. Revue neurologique, 181(3), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2024.12.001 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39765442/).

2. Boccuni, L., Meyer, S., Kessner, S. S., De Bruyn, N., Essers, B., Cheng, B., Thomalla, G., Peeters, A., Sunaert, S., Duprez, T., Marinelli, L., Trompetto, C., Thijs, V., & Verheyden, G. (2018). Is There Full or Proportional Somatosensory Recovery in the Upper Limb After Stroke? Investigating Behavioral Outcome and Neural Correlates. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 32(8), 691–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968318787060 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29991331/).

3. Carey, L. M., Matyas, T. A., & Oke, L. E. (1993). Sensory loss in stroke patients: effective training of tactile and proprioceptive discrimination. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 74(6), 602–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9993(93)90158-7 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8503750/).

4. Carey, L. M., Oke, L. E., & Matyas, T. A. (1996). Impaired limb position sense after stroke: a quantitative test for clinical use. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 77(12), 1271–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90192-6 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8976311/).

5. Carey, L. M., & Matyas, T. A. (2005). Training of somatosensory discrimination after stroke: facilitation of stimulus generalization. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 84(6), 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.phm.0000159971.12096.7f (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15905657/).

6. Carey, L., Macdonell, R., & Matyas, T. A. (2011). SENSe: Study of the Effectiveness of Neurorehabilitation on Sensation: a randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 25(4), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968310397705 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21350049/).

7. Carey, L. M., Abbott, D. F., Lamp, G., Puce, A., Seitz, R. J., & Donnan, G. A. (2016). Same Intervention-Different Reorganization: The Impact of Lesion Location on Training-Facilitated Somatosensory Recovery After Stroke. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 30(10), 988–1000. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968316653836 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27325624/).

8. Carey, L. M., Matyas, T. A., & Baum, C. (2018). Effects of Somatosensory Impairment on Participation After Stroke. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 72(3), 7203205100p1–7203205100p10. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2018.025114 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29689179/).

9. Chilvers, M., Low, T., Rajashekar, D., & Dukelow, S. (2024). White matter disconnection impacts proprioception post-stroke. PloS one, 19(9), e0310312. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0310312 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39264972/).

10. Conforto, A. B., Dos Anjos, S. M., Bernardo, W. M., Silva, A. A. D., Conti, J., Machado, A. G., & Cohen, L. G. (2018). Repetitive Peripheral Sensory Stimulation and Upper Limb Performance in Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 32(10), 863–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968318798943 (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6404964/#SM1).

11. Cuesta, C. (2016). El procesamiento de la información somatosensorial y la funcionalidad de la mano en pacientes con daño cerebral adquirido (https://burjcdigital.urjc.es/items/609ccf16-4688-0c23-e053-6f19a8c0ba23).

12. De Bruyn, N., Meyer, S., Kessner, S. S., Essers, B., Cheng, B., Thomalla, G., Peeters, A., Sunaert, S., Duprez, T., Thijs, V., Feys, H., Alaerts, K., & Verheyden, G. (2018). Functional network connectivity is altered in patients with upper limb somatosensory impairments in the acute phase post stroke: A cross-sectional study. PloS one, 13(10), e0205693. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205693 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30312350/).

13. De Bruyn, N., Saenen, L., Thijs, L., Van Gils, A., Ceulemans, E., Essers, B., Alaerts, K., & Verheyden, G. (2021). Brain connectivity alterations after additional sensorimotor or motor therapy for the upper limb in the early-phase post stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Brain communications, 3(2), fcab074. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab074 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33937771/).

14. Grant, V. M., Gibson, A., & Shields, N. (2018). Somatosensory stimulation to improve hand and upper limb function after stroke-a systematic review with meta-analyses. Topics in stroke rehabilitation, 25(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2017.1389054 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29050540/).

15. Kessner, S. S., Schlemm, E., Cheng, B., Bingel, U., Fiehler, J., Gerloff, C., & Thomalla, G. (2019). Somatosensory Deficits After Ischemic Stroke. Stroke, 50(5), 1116–1123. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023750 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30943883/).

16. Ladera V, Perea MV. Agnosias auditivas, somáticas y táctiles. Rev Neuropsicol y Neurociencias. 2015;15(1):87–108 (http://revistaneurociencias.com/index.php/RNNN/article/view/82).

17. Laufer, Y., & Elboim-Gabyzon, M. (2011). Does sensory transcutaneous electrical stimulation enhance motor recovery following a stroke? A systematic review. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 25(9), 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968310397205 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21746874/).

18. Lederman, S. J., & Klatzky, R. L. (1987). Hand movements: a window into haptic object recognition. Cognitive psychology, 19(3), 342–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(87)90008-9 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3608405/).

19. Meyer, S., De Bruyn, N., Lafosse, C., Van Dijk, M., Michielsen, M., Thijs, L., Truyens, V., Oostra, K., Krumlinde-Sundholm, L., Peeters, A., Thijs, V., Feys, H., & Verheyden, G. (2016). Somatosensory Impairments in the Upper Limb Poststroke: Distribution and Association With Motor Function and Visuospatial Neglect. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 30(8), 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968315624779 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26719352/).

20. Miguel-Quesada, C., Zaforas, M., Herrera-Pérez, S., Lines, J., Fernández-López, E., Alonso-Calviño, E., Ardaya, M., Soria, F. N., Araque, A., Aguilar, J., & Rosa, J. M. (2023). Astrocytes adjust the dynamic range of cortical network activity to control modality-specific sensory information processing. Cell reports, 42(8), 112950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112950 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37543946/).

21. Moore, R. T., Piitz, M. A., Singh, N., Dukelow, S. P., & Cluff, T. (2024). The independence of impairments in proprioception and visuomotor adaptation after stroke. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation, 21(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-024-01360-7 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38762552/).

22. Opsommer, E., Zwissig, C., Korogod, N., & Weiss, T. (2016). Effectiveness of temporary deafferentation of the arm on somatosensory and motor functions following stroke: a systematic review. JBI database of systematic reviews and implementation reports, 14(12), 226–257. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003231 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28009677/).

23. Sharififar, S., Shuster, J. J., & Bishop, M. D. (2018). Adding electrical stimulation during standard rehabilitation after stroke to improve motor function. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine, 61(5), 339–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2018.06.005 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29958963/).

24. Stolk-Hornsveld, F., Crow, J. L., Hendriks, E. P., van der Baan, R., & Harmeling-van der Wel, B. C. (2006). The Erasmus MC modifications to the (revised) Nottingham Sensory Assessment: a reliable somatosensory assessment measure for patients with intracranial disorders. Clinical rehabilitation, 20(2), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215506cr932oa (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16541937/).

25. Turville, M., Carey, L. M., Matyas, T. A., & Blennerhassett, J. (2017). Change in Functional Arm Use Is Associated With Somatosensory Skills After Sensory Retraining Poststroke. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 71(3), 7103190070p1–7103190070p9. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.024950 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28422633/).

26. Turville, M. L., Cahill, L. S., Matyas, T. A., Blennerhassett, J. M., & Carey, L. M. (2019). The effectiveness of somatosensory retraining for improving sensory function in the arm following stroke: a systematic review. Clinical rehabilitation, 33(5), 834–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215519829795 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30798643/).

27. Villar Ortega, E., Buetler, K. A., Aksöz, E. A., & Marchal-Crespo, L. (2024). Enhancing touch sensibility with sensory electrical stimulation and sensory retraining. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation, 21(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-024-01371-4 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38750521/).

28. Yilmazer, C., Boccuni, L., Thij

En este episodio, nos sumergimos en la vía motora más determinante del sistema nervioso humano: el tracto corticoespinal. A través de un recorrido detallado por su evolución, desarrollo, anatomía y función, analizamos por qué esta vía representa la gran apuesta evolutiva por la motricidad fina y por qué su lesión tiene consecuencias tan devastadoras. Hablamos de neurofisiología, de plasticidad, de evaluación con TMS y DTI, de terapias intensivas, neuromodulación, farmacología, robótica y de las posibilidades —y límites— reales de su regeneración tras un ictus. Si te interesa entender en profundidad cómo se ejecuta el movimiento voluntario y qué ocurre cuando esa vía falla, este episodio es para ti.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Alawieh, A., Tomlinson, S., Adkins, D., Kautz, S., & Feng, W. (2017). Preclinical and Clinical Evidence on Ipsilateral Corticospinal Projections: Implication for Motor Recovery. Translational stroke research, 8(6), 529–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-017-0551-5 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28691140/).

2. Cho, M. J., Yeo, S. S., Lee, S. J., & Jang, S. H. (2023). Correlation between spasticity and corticospinal/corticoreticular tract status in stroke patients after early stage. Medicine, 102(17), e33604. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000033604 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37115067/).

3. Dalamagkas, K., Tsintou, M., Rathi, Y., O'Donnell, L. J., Pasternak, O., Gong, X., Zhu, A., Savadjiev, P., Papadimitriou, G. M., Kubicki, M., Yeterian, E. H., & Makris, N. (2020). Individual variations of the human corticospinal tract and its hand-related motor fibers using diffusion MRI tractography. Brain imaging and behavior, 14(3), 696–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-018-0006-y (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30617788/).

4. Duque-Parra, Jorge Eduardo, Mendoza-Zuluaga, Julián, & Barco-Ríos, John. (2020). El Tracto Cortico Espinal: Perspectiva Histórica. International Journal of Morphology, 38(6), 1614-1617. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022020000601614 (https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-95022020000601614).

5. Eyre, J. A., Miller, S., Clowry, G. J., Conway, E. A., & Watts, C. (2000). Functional corticospinal projections are established prenatally in the human foetus permitting involvement in the development of spinal motor centres. Brain : a journal of neurology, 123 ( Pt 1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/123.1.51 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10611120/).

6. He, J., Zhang, F., Pan, Y., Feng, Y., Rushmore, J., Torio, E., Rathi, Y., Makris, N., Kikinis, R., Golby, A. J., & O'Donnell, L. J. (2023). Reconstructing the somatotopic organization of the corticospinal tract remains a challenge for modern tractography methods. Human brain mapping, 44(17), 6055–6073. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.26497 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37792280/).

7. Huang, L., Yi, L., Huang, H., Zhan, S., Chen, R., & Yue, Z. (2024). Corticospinal tract: a new hope for the treatment of post-stroke spasticity. Acta neurologica Belgica, 124(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-023-02377-w (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37704780/).

8. Kazim, S. F., Bowers, C. A., Cole, C. D., Varela, S., Karimov, Z., Martinez, E., Ogulnick, J. V., & Schmidt, M. H. (2021). Corticospinal Motor Circuit Plasticity After Spinal Cord Injury: Harnessing Neuroplasticity to Improve Functional Outcomes. Molecular neurobiology, 58(11), 5494–5516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-021-02484-w (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34341881/).

9. Kwon, Y. M., Kwon, H. G., Rose, J., & Son, S. M. (2016). The Change of Intra-cerebral CST Location during Childhood and Adolescence; Diffusion Tensor Tractography Study. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 10, 638. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00638 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28066209/).

10. Lemon, R. N., Landau, W., Tutssel, D., & Lawrence, D. G. (2012). Lawrence and Kuypers (1968a, b) revisited: copies of the original filmed material from their classic papers in Brain. Brain : a journal of neurology, 135(Pt 7), 2290–2295. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws037 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22374938/).

11. Li S. (2017). Spasticity, Motor Recovery, and Neural Plasticity after Stroke. Frontiers in neurology, 8, 120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00120 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28421032/).

12. Liu, Z., Chopp, M., Ding, X., Cui, Y., & Li, Y. (2013). Axonal remodeling of the corticospinal tract in the spinal cord contributes to voluntary motor recovery after stroke in adult mice. Stroke, 44(7), 1951–1956. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001162 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23696550/).

13. Liu, K., Lu, Y., Lee, J. K., Samara, R., Willenberg, R., Sears-Kraxberger, I., Tedeschi, A., Park, K. K., Jin, D., Cai, B., Xu, B., Connolly, L., Steward, O., Zheng, B., & He, Z. (2010). PTEN deletion enhances the regenerative ability of adult corticospinal neurons. Nature neuroscience, 13(9), 1075–1081. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2603 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20694004/).

14. Schieber M. H. (2007). Chapter 2 Comparative anatomy and physiology of the corticospinal system. Handbook of clinical neurology, 82, 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0072-9752(07)80005-4 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18808887/).

15. Stinear, C. M., Barber, P. A., Smale, P. R., Coxon, J. P., Fleming, M. K., & Byblow, W. D. (2007). Functional potential in chronic stroke patients depends on corticospinal tract integrity. Brain : a journal of neurology, 130(Pt 1), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl333 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17148468/).

16. Usuda, N., Sugawara, S. K., Fukuyama, H., Nakazawa, K., Amemiya, K., & Nishimura, Y. (2022). Quantitative comparison of corticospinal tracts arising from different cortical areas in humans. Neuroscience research, 183, 30–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2022.06.008 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35787428/).

17. Ward, N. S., Brander, F., & Kelly, K. (2019). Intensive upper limb neurorehabilitation in chronic stroke: outcomes from the Queen Square programme. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 90(5), 498–506. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-319954 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30770457/).

18. Welniarz, Q., Dusart, I., & Roze, E. (2017). The corticospinal tract: Evolution, development, and human disorders. Developmental neurobiology, 77(7), 810–829. https://doi.org/10.1002/dneu.22455 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27706924/).

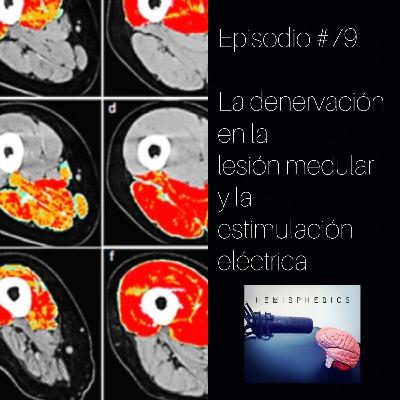

En este episodio, profundizamos en uno de los fenómenos más devastadores pero menos comprendidos en neurorrehabilitación: la denervación muscular tras una lesión medular. A través de una revisión exhaustiva de la literatura científica y de la experiencia clínica, abordamos qué ocurre realmente con los músculos que han perdido su inervación, cómo se transforman con el tiempo y qué posibilidades tenemos para intervenir. Hablamos sobre neurofisiología, degeneración axonal, fases de la denervación, y cómo la estimulación eléctrica —especialmente con pulsos largos— puede modificar el curso degenerativo incluso años después de la lesión. Exploramos también el Proyecto RISE, los protocolos clínicos actuales y las implicaciones terapéuticas reales de aplicar electroestimulación en músculos completamente denervados. Si trabajas en neurorrehabilitación o te interesa la ciencia aplicada a la recuperación funcional, este episodio es para ti.

Referencias del episodio:

1. Alberty, M., Mayr, W., & Bersch, I. (2023). Electrical Stimulation for Preventing Skin Injuries in Denervated Gluteal Muscles-Promising Perspectives from a Case Series and Narrative Review. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 13(2), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13020219 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36673029/).

2. Beauparlant, J., van den Brand, R., Barraud, Q., Friedli, L., Musienko, P., Dietz, V., & Courtine, G. (2013). Undirected compensatory plasticity contributes to neuronal dysfunction after severe spinal cord injury. Brain : a journal of neurology, 136(Pt 11), 3347–3361. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt204 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24080153/).

3. Bersch, I., & Fridén, J. (2021). Electrical stimulation alters muscle morphological properties in denervated upper limb muscles. EBioMedicine, 74, 103737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103737 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34896792/).

4. Bersch, I., & Mayr, W. (2023). Electrical stimulation in lower motoneuron lesions, from scientific evidence to clinical practice: a successful transition. European journal of translational myology, 33(2), 11230. https://doi.org/10.4081/ejtm.2023.11230 (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10388603/).

5. Burnham, R., Martin, T., Stein, R., Bell, G., MacLean, I., & Steadward, R. (1997). Skeletal muscle fibre type transformation following spinal cord injury. Spinal cord, 35(2), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3100364 (Burnham, R., Martin, T., Stein, R., Bell, G., MacLean, I., & Steadward, R. (1997). Skeletal muscle fibre type transformation following spinal cord injury. Spinal cord, 35(2), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3100364).

6. Carlson B. M. (2014). The Biology of Long-Term Denervated Skeletal Muscle. European journal of translational myology, 24(1), 3293. https://doi.org/10.4081/ejtm.2014.3293 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26913125/).

7. Carraro, U., Boncompagni, S., Gobbo, V., Rossini, K., Zampieri, S., Mosole, S., Ravara, B., Nori, A., Stramare, R., Ambrosio, F., Piccione, F., Masiero, S., Vindigni, V., Gargiulo, P., Protasi, F., Kern, H., Pond, A., & Marcante, A. (2015). Persistent Muscle Fiber Regeneration in Long Term Denervation. Past, Present, Future. European journal of translational myology, 25(2), 4832. https://doi.org/10.4081/ejtm.2015.4832 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26913148/).

8. Chandrasekaran, S., Davis, J., Bersch, I., Goldberg, G., & Gorgey, A. S. (2020). Electrical stimulation and denervated muscles after spinal cord injury. Neural regeneration research, 15(8), 1397–1407. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.274326 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31997798/).

9. Ding, Y., Kastin, A. J., & Pan, W. (2005). Neural plasticity after spinal cord injury. Current pharmaceutical design, 11(11), 1441–1450. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612053507855 (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3562709/).

10. Dolbow, D. R., Bersch, I., Gorgey, A. S., & Davis, G. M. (2024). The Clinical Management of Electrical Stimulation Therapies in the Rehabilitation of Individuals with Spinal Cord Injuries. Journal of clinical medicine, 13(10), 2995. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13102995 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38792536/).

11. Hofer, C., Mayr, W., Stöhr, H., Unger, E., & Kern, H. (2002). A stimulator for functional activation of denervated muscles. Artificial organs, 26(3), 276–279. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1594.2002.06951.x (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11940032/).

12. Kern, H., Hofer, C., Mödlin, M., Forstner, C., Raschka-Högler, D., Mayr, W., & Stöhr, H. (2002). Denervated muscles in humans: limitations and problems of currently used functional electrical stimulation training protocols. Artificial organs, 26(3), 216–218. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1594.2002.06933.x (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11940016/).

13. Kern, H., Salmons, S., Mayr, W., Rossini, K., & Carraro, U. (2005). Recovery of long-term denervated human muscles induced by electrical stimulation. Muscle & nerve, 31(1), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.20149 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15389722/).

14. Kern, H., Rossini, K., Carraro, U., Mayr, W., Vogelauer, M., Hoellwarth, U., & Hofer, C. (2005). Muscle biopsies show that FES of denervated muscles reverses human muscle degeneration from permanent spinal motoneuron lesion. Journal of rehabilitation research and development, 42(3 Suppl 1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1682/jrrd.2004.05.0061 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16195962/).

15. Kern, H., Carraro, U., Adami, N., Hofer, C., Loefler, S., Vogelauer, M., Mayr, W., Rupp, R., & Zampieri, S. (2010). One year of home-based daily FES in complete lower motor neuron paraplegia: recovery of tetanic contractility drives the structural improvements of denervated muscle. Neurological research, 32(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1179/174313209X385644 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20092690/).

16. Kern, H., & Carraro, U. (2014). Home-Based Functional Electrical Stimulation for Long-Term Denervated Human Muscle: History, Basics, Results and Perspectives of the Vienna Rehabilitation Strategy. European journal of translational myology, 24(1), 3296. https://doi.org/10.4081/ejtm.2014.3296 (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4749003/).

17. Kern, H., Hofer, C., Loefler, S., Zampieri, S., Gargiulo, P., Baba, A., Marcante, A., Piccione, F., Pond, A., & Carraro, U. (2017). Atrophy, ultra-structural disorders, severe atrophy and degeneration of denervated human muscle in SCI and Aging. Implications for their recovery by Functional Electrical Stimulation, updated 2017. Neurological research, 39(7), 660–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616412.2017.1314906 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28403681/).

18. Kern, H., & Carraro, U. (2020). Home-Based Functional Electrical Stimulation of Human Permanent Denervated Muscles: A Narrative Review on Diagnostics, Managements, Results and Byproducts Revisited 2020. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 10(8), 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10080529 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32751308/).

19. Ko H. Y. (2018). Revisit Spinal Shock: Pattern of Reflex Evolution during Spinal Shock. Korean journal of neurotrauma, 14(2), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.13004/kjnt.2018.14.2.47 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30402418/).

20. Mittal, P., Gupta, R., Mittal, A., & Mittal, K. (2016). MRI findings in a case of spinal cord Wallerian degeneration following trauma. Neurosciences (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), 21(4), 372–373. https://doi.org/10.17712/nsj.2016.4.20160278 (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5224438/).

21. Pang, Q. M., Chen, S. Y., Xu, Q. J., Fu, S. P., Yang, Y. C., Zou, W. H., Zhang, M., Liu, J., Wan, W. H., Peng, J. C., & Zhang, T. (2021). Neuroinflammation and Scarring After Spinal Cord Injury: Therapeutic Roles of MSCs on Inflammation and Glial Scar. Frontiers in immunology, 12, 751021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.751021 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34925326/).

22. Schick, T. (Ed.). (2022). Functional electrical stimulation in neurorehabilitation: Synergy effects of technology and therapy. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90123-3 (https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-90123-3).

23. Swain, I., Burridge, J., & Street, T. (Eds.). (2024). Techniques and technologies in electrical stimulation for neuromuscular rehabilitation. The Institution of Engineering and Technology. https://shop.theiet.org/techniques-and-technologies-in-electrical-stimulation-for-neuromuscular-rehabilitation

24. van der Scheer, J. W., Goosey-Tolfrey, V. L., Valentino, S. E., Davis, G. M., & Ho, C. H. (2021). Functional electrical stimulation cycling exercise after spinal cord injury: a systematic review of health and fitness-related outcomes. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation, 18(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-021-00882-8 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34118958/).

25. Xu, X., Talifu, Z., Zhang, C. J., Gao, F., Ke, H., Pan, Y. Z., Gong, H., Du, H. Y., Yu, Y., Jing, Y. L., Du, L. J., Li, J. J., & Yang, D. G. (2023). Mechanism of skeletal muscle atrophy after spinal cord injury: A narrative review. Frontiers in nutrition, 10, 1099143. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1099143 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36937344/).

26. Anatomical Concepts: https://www.anatomicalconcepts.com/articles

En este episodio entrevistamos a Bernat de las Heras, investigador en neurorehabilitación y experto en neuroplasticidad post-ictus. Desde su formación inicial en Ciencias del Deporte hasta su doctorado en la Universidad McGill, Bernat ha explorado cómo el ejercicio cardiovascular —en especial el aeróbico y HIIT— puede modular la neuroplasticidad cerebral tras un ictus. Bernat nos explica los beneficios y limitaciones del entrenamiento interválico de alta intensidad, su percepción por parte de los pacientes, y cómo combinarlo de forma efectiva con otras estrategias terapéuticas. Hablamos también de aprendizaje y localización de la lesión. Una conversación profunda y práctica para entender los límites actuales de la evidencia, y al mismo tiempo, abrir nuevas vías para la rehabilitación neurológica individualizada.

Referencias del episodio:

1) Ploughman, M., Attwood, Z., White, N., Doré, J. J., & Corbett, D. (2007). Endurance exercise facilitates relearning of forelimb motor skill after focal ischemia. The European journal of neuroscience, 25(11), 3453–3460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05591.x (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17553014/).

2) Jeffers, M. S., & Corbett, D. (2018). Synergistic Effects of Enriched Environment and Task-Specific Reach Training on Poststroke Recovery of Motor Function. Stroke, 49(6), 1496–1503. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.020814 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29752347/).

3) De Las Heras, B., Rodrigues, L., Cristini, J., Moncion, K., Ploughman, M., Tang, A., Fung, J., & Roig, M. (2024). Measuring Neuroplasticity in Response to Cardiovascular Exercise in People With Stroke: A Critical Perspective. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 38(4), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/15459683231223513 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38291890/).