Discover In Search of the Mystery of God

In Search of the Mystery of God

80 Episodes

Reverse

Silence. Absence of speech. Heads bowed. Time transcended. Two minutes of eternity. Strangers' names sounded aloud. Anchor still holding. Lighthouse in the storm. Death faced. Or not.Our acts of remembrance are presented in many different ways. But not all are helpful. This sermon explores the real point of remembrance.

In the depths of our inner being exists, in each of us, a part that no one else ever sees. Its the place where sometimes even we are too afraid to go. Its where our deepest secrets lie, the things we are too terrified to let others know about us; where the disappointments that have crushed us are buried; where memories of being rejected, or humiliated, or bullied, when we have been so badly hurt it feels like a sword has run through us, are shut away in the dark because otherwise they would overwhelm and drown us. Where we know how we have sometimes treated others, said and done unthinkably unkind and cruel acts of which we are so ashamed we can't bear to admit them. And it leaves us with this deep sense of isolation and utter alone-ness.Most of us bury this part of our soul, sensing that no-one would want anything to do with us if they really knew what we were like. So we try to compensate, perhaps by presenting an image of ourselves to the world by which we would like to be known. We choose our clothes, the way we look, our manner with others, to convey a particular impression, a mask behind which to hide, carefully cultivated in front of a mirror. Mirrors. Those silvered surfaces that reflect back the superficial us we want others to see. Where would we be without mirrors and photographs, and the rise of the ubiquitous 'selfie'?But this hidden part is the 'real' us - the rest is all facade. And it is this hidden part that God calls to. In the story of the Fall in Genesis 3, after Adam and Eve have eaten the apple, they realise they are 'naked', exposed to each other. They both feel this incredible shame and guilt, and so they hide from each other and from God. Its exactly the same with each of us. The story of Adam and Eve is the story of Everyman - we hide ourselves, alone and out of sight, as George Herbert so precisely puts it, 'guilty of dust and sin'. But in the cool of the day, God walks in the garden and calls out to them 'where are you?''Where are you?'That's the question God asks of each of us.Its arguably the most profound question in the Bible. 'Where are you?'Dare we answer?'But what if...?'The rub is, of course, that he already knows exactly where we are, why we are hiding, and, most frighteningly, what we are hiding. And yet his love for each of us remains infinitely deeper than our worst fear. This is the Mystery of God: how is it possible for God to know what we are really like and still love us?The question, then, is whether we are willing to be found...The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for the 12th Sunday after Trinity 2024Poem: 'The Raven' by Norman NicholsonOT: 1 Kings 2:10-12, 3:3-14NT: Eph 5:15-20Gospel: John 6:51-58

She was incredibly beautiful. Lithe, graceful, shapely, bronze-skinned with full and dark flowing hair, nubile. Who could resist her? It all started with a glance out the window that turned into a lingering gaze. Did she know he might see her, bathing out there on the roof in the evening sun? She was so…tantalising. He was mesmerised.It is the simplest of things. But at what point did he cross a threshold? Was it the glance? No, that was impulsive, accidental coincidence and he was shocked. Was it when he became transfixed, rooted to the spot, unable to tear his eyes away? Surely not – such beauty is created to be beheld, and how he appreciated such delectable beauty. Perhaps it was when he couldn’t shake the image of her from his mind as he lay on his bed that night? No, he hadn’t done anything wrong, it couldn’t have been then. But of course, everything starts in the imagination…Years later, David’s heir was to say ‘If anyone looks at a woman lustfully he has already committed adultery with her in his heart…’But just now, he had absolutely no idea how that lingering gaze was to lead to the destruction, not only of his family, but of the entire kingdom of Israel. No one did.The nature of sin is that it reaches out in unexpected ways to enmesh, suck in, cling to, like tentacles that drag us down to the deep. It feeds on darkness and deception, jealousy and self-interest, fear and guilt. It destroys trust, faithfulness, honesty and kindness, generosity and love. How do we identify sin? Easy. It always has ‘I’ at the centre: s-I-n.The trouble is, we don’t even see this as an issue any more. The new Olympian mantra repeated over and over is ‘I’m really proud of myself.’ At other times we say ‘I deserve it’, or ‘I’m worth it,’ as we desperately try to suppress the niggling doubt that we're not. Others tells us ‘you need to forgive yourself’ as if we have the right or the power, or to ‘love yourself’, but love means laying down your life for another, so how does that work?All of these point to a reversal of the true nature of love, a dependence and centring on the self instead of God and others; a distortion and corruption of the source of life into an imploding, self-destructive force that ultimately leads to the annihilation, not only of ourselves, or of our communities, or even society, but of entire species, ecosystems, and the climate. In a word, death.And so the Bread of life enters our deep, dark, tentacled world to bring us back up to the surface, where we can gulp the Spirit, and breathe at last in the light…The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for the 9th Sunday after Trinity, 2024 (Year B)Poem: 'The Bright Field' by RS ThomasOT: 2 Sam 11:1-15NT: Eph 3:14-endGospel: Jn 6:1-21

Good Friday service around the Bewcastle Cross including a recital of the Anglo-Saxon poem 'The Dream of The Rood'.

The Epiphany, by its nature, is enigmatic. On the 6th January every year, we celebrate the visit of the wise men from the east to see the baby king in the stable with his mother and father, bringing their gifts. We call it The Epiphany because it represents the recognition of God's coming by the Gentile (that's us) world. 'Epiphany', that moment of sudden awakening or realisation.But what was realised? Who noticed? Notoriously, Herod became furious when he realised he was tricked by the magi, and sent his soldiers to slaughter all the boys aged two and under in and around Bethlehem, perhaps between six and twenty children, in the hope of killing the baby Jesus and eliminating any competition for his throne.But apart from the magi and the shepherds, we are not told of anyone else having a clue about the significance of Jesus' birth. Some 'epiphany'!TS Eliot, in his famous poem 'Journey of the Magi', takes up this theme of the enigmatic nature of the Epiphany, telling it as a story seen from the perspective of the magi. But it is a journey riddled with pain, difficulty, and disappointment. There are moments that flicker with hope, 'Then at dawn...', but they soon fade back into the grey dampness of the cold world. They wander, searching, through the valley of the shadow of Christ's death, unknowingly, until they reach their moment of 'epiphany': 'It was (you may say) satisfactory' in the most underwhelming of climaxes.The journey, however, is for us. We are Eliot's magi, on what seems a hard, bitter, and foolish journey with almost nothing to show at the end, except a morsel of bread made from the flour from 'the mill beating the darkness', and the wine from 'the vines-leaves over the lintel' and the 'empty wine-skins' being kicked under the table. But the encounter changes us, and we are left having died and been born again, no longer at peace with the idolatry of the world around us, waiting, longing for the old white horse in the meadow to, at last, carry its white rider...The Bewcastle benefice sermon for the first Sunday of Epiphany 2024.

The Advent calling is to a different path, set in the approach to the darkest part of the year, when the forces that would exploit us by playing to our interests of self-preservation are most powerful. The prayer 'Come' requires us to prepare ourselves, to be brutally honest about who we are, both in our vulnerability and in our self-interest. For when we are, terrifying as this may be, we are met by the One who loves us with a passion that will lead him to the Cross on our behalf.Dare we pray the prayer? Dare we not?Bewcastle Benefice sermon for Advent Sunday 2023.Poem: 'Advent Calendar' by Rowan WilliamsOT: Isaiah 64:1-9NT: 1 Cor 1:3-9Gospel: Mark 13:24-end

For over 2000 years Japanese women, known as ama, have descended to depths of over 30m underwater, in a single breath lasting over two minutes, in search of pearls. They descend into the darkness where all colour has vanished. Only silence, shadows and outlines remain. It is a place of extreme cold and danger where few ever venture. They do it 100-150 times a day, and continue into their eighties, needing to retrieve a ton of oysters in their nets to find four or five decent pearls. Not many of us will ever experience the physical and physiological hardship of such a way of life.But many of us do experience the depth of darkness of physical or emotional pain, loneliness, loss, or other forms of suffering. It can seem like a place without end, without hope, devoid of joy or happiness, no 'light at the end of the tunnel', just continual darkness. For some, the weight of bearing pain, or caring for others, can be relentless, lasting for years, For others, traumatised by experiences of years ago, or who have suffered abuse of one form or another, it can seem like being trapped in a suffocating cage from which there is no way out.Paul, in his letter to the church in Rome, grapples with the depths on his own failure as a human being. Although he begins with a summary of the mess the world is in (chapter 1), describing our struggles with fallenness, he descends further and further into the darkness of our own, and ultimately his, sinful nature (chapter 7) - "For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing. Wretched man that I am. Who will deliver me from this body of death?"It is true that he passes the beautiful corals of Christ's work on his way down (chapters 5 and 6), and they hint at the treasure below. But he must make that descent himself first, before he can find the pearl of great price for which he seeks in the darkness of his innermost despair.The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for the 8th Sunday after Trinity, 2023Poem: 'The Bright Field' by RS ThomasOT: Gen 29:15-28NT: Rom 8:26-endGospel: Mat 13:31-33,44-52

Duplicity. Abraham complies with his wife's scheming and then denies his firstborn. Isaac is tricked by his second-born with the help of his mother's plotting. Jacob indulges his wives' bitter rivalry, and so spawns the twelve tribes of Israel. The Patriarchs of Israel are a sorry bunch, for whom 'integrity' was not a word that carried much currency. And yet. And yet God chose them. Promised to bless the world through them - schemers and dreamers though they were.But perhaps it was the dreaming for which they were chosen? All of them 'heard' God speak words of promise. What does it mean to 'hear' God? How do you know it's God speaking and not your own imagination, or madness? Then again, they were all exceptionally wealthy, so perhaps they weren't mad after all.But Jacob has fled from his brother, having deceived his father into giving him the blessing of the firstborn, which his brother, in a moment of rash stupidity (and probably joking), had agreed to give him in exchange for a bowl of stew, and been sent off by his mother to her brother's household in search of a wife.Alone and in the darkness of the wilderness, Jacob dreams a dream: God promises to bless his offspring and the whole world. So he calls the place 'beth-el', house of God.But what, really, is this 'house of God' that Jacob attempts to locate in the wilderness? Paul, in his majestic letter to the Romans, unpacks the promise, and our place in it.Poem: 'Seabirds' Blessing' by Alice OswaldOT: Gen 28:10-19aNT: Rom 8:12-25Gospel: Mat 13:24-30, 36-43

'Are you sitting comfortably? Then I'll begin. A long time ago...'We love stories. From our earliest days to old age we love listening to, and telling, stories. They are how we make sense of the world around us, how we first encounter 'others' in our imaginations, and they are how we form our collective memories that bind us as societies. Jesus was a master story-teller; his stories, called parables, played off the collective stories familiar to his listeners, and turned out to be enigmatic, challenging, full of surprises and unexpected outcomes. His stories are crafted to disrupt in order to allow light to enter the dark places of our hearts.The problem, though, is that the darkness in our hearts only enters through stories as well. Bad stories. Stories that speak against, stories of victimisation and discrimination, of separation and boundaries, stories that reinforce prejudice. These are the stories that feed self-pity and blame others. We see it all around in families, local communities, society, politics, nations. At every scale stories feed and shape our beliefs.The story Jesus tells is of the end of all these dark stories and the beginning of the new story, which is the oldest one of all. It is the story of death; Christ's death, our death. And then birth, with the offering of a new beginning, where, like children, we learn there are no borders other than in the mind. 'There is no Jew or Gentile, no slave or free, no male or female, for we are all one in Christ.' This is the nature and gift of baptism. The new story is of the unquenchable love of God poured into the world, poured into our hearts.The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for the 3rd Sunday of Trinity (Year A).Poem: 'The Island of The Children' by George Mackay BrownOT: Gen 21:8-21NT: Rom 6:1b-11Gospel: Mat 10:24-39

'Deep calls to deep in the roar of your waterfalls' shouts the psalmist through the drenching thunder.So many of us are nervous souls, battered down by cares and worries, apprehensive for loved ones or ourselves. The experience of hurt and disappointment has left us timid and small. The adventure of childhood has long since been buried to allow us to cope with our journey towards the end. The thrill of life is now often found only in a book or on a screen. We manage our environments as best we can - warm homes, stocked cupboards, comfortable cars. Even so, financial worries still fret away - will we be able to afford next month? Church, too, is sedate and safe, routine and reassuring. Danger is best avoided with a thorough risk assessment. Our small worlds are contracted to a single stone in a bare field.The wilderness is a long way from here. Thankfully?I read a poem recently, about Christ being crucified on "the skull of the world". It's reference, of course, to the hill on which he was crucified, called 'Golgotha', meaning 'place of the skull.' But it captures something far deeper about the deadness of the world, the deadness of humanity, on which and for which he died. The poem goes on to speak of the one who hungered yet fed others, who thirsted while inviting others to come to him to drink, who raised the dead to life while dying himself. As the mockers so astutely put it 'he saved others, he cannot save himself.' How? And why?Christ lived under the thundering cataract of God, the swirling presence of the Holy Spirit. We have been given so many images of this Spirit; water, wind, fire, and none of them are comfortable, not even the dove, who 'drove' Jesus out into the wilderness. And yet the Spirit is called the Comforter.Perhaps its time we rediscovered this Spirit of God.The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for Pentecost, Year A.Poem: a few verses from 'Little Gidding' by TS EliotNT: Acts 2:1-21Gospel: John 20:19-23

In 1649 to St George's Hill

A ragged band they called the "Diggers"

Came to show the people's will.

They defied the landlords, they defied the laws;

They were the dispossessed reclaiming what was theirs.

'We come in peace' they said 'to dig and sow.

We come to work the lands in common

And to make the wastelands grow;

This earth divided we will make whole

So it will be a common treasury for all.'

So begins a song by Leon Rosselson about Gerard Winstanley and the first Diggers - one that I sometimes sing at our folk evenings. The Diggers arrived at St George's Hill in Weybridge, Surrey, in April of 1649 as a small group of men and women who had lost their homes during the Civil War and due to Enclosure. By August they had been driven from the land by nearby landowners and resettled a short distance away at Cobham, still in Surrey. By April of the next year the local clergyman, another landowner, had managed to force them off that land also. It is a sorry and uncomfortable tale.For such a briefly-lived movement, the Diggers have had an astonishingly disproportionate influence, still inspiring young and old alike. That fact, alone, speaks of a resonance deep within us that yearns for a different way of being in the world.Winstanley's own inspiration, itself, came from the book of Acts, chapter 2, verses 44-45:And all who believed were together and had all things in common.

And they were selling their possessions and belongings and distributing the proceeds to all,

as any had need.

But this wasn't the first time in English history that the Bible had been the inspiration for understanding the equality of all. In 1381 the Peasant's Revolt was stirred by the preaching of the priest John Ball, credited with the first protest rhyme in the English language, "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the Gentleman?" Ball worked alongside John Wycliffe, who was translating the Bible into the English vernacular for the first time in history. Now the Word of God was reaching the Commoners and it was dangerous stuff.This is some of the history with which we have to contend when we read Acts 2. It is difficult because we don't take it very seriously any more - it poses far too much of a threat to our established way of life. So we hide behind excuses like 'history proves its entirely impractical to live like that anyway.' And its true, many attempts to live a 'common life' have ended in failure.Many, but not all. Monastic communities have been since the first centuries of the Church's existence as a continuation of precisely this description of the Church in Acts. They still continue today. Of course, there are multiple notorious examples where these 'communities' have been farcical mockeries, even evil parodies, of their calling through history. But there are also countless others, untold and unsung, where true life has been lived.The question then falls to us as to how we are to respond because, despite what we may tell ourselves, possession and wealth are not the answer the world would have us believe, and that, generally, we are inclined to accept. If we were, somehow, to find a way of walking to a different drum, what would the world look like then...The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for the 4th Sunday of Easter.Poem: 'Sudden Shower' by John ClareNT: Acts 2:42-47Gospel: John 10:1-10

Hope belongs to the world of belief; it has direction and a future. Atheism, in contrast, and by definition, has only chaos, and therefore neither. We, all of us, depend on hope, live our lives in hope, even as we rest in the moment. But hope disappointed can be shattering, destructive, devastating. It can ruin a soul and lead to utter darkness. It is the place of hell.So how do we choose what to hope for? How do we know who or what to trust and believe in? A topical question in a world of 'fake news'. A cynic's answer might be to trust no one but yourself. But only the arrogant would be so foolish, for we all die, and what is 'hope' that ceases to exist when we do?Those seven miles of the road from Jerusalem to Emmaus were the seven miles of holiness. On them, the unknown stranger picked up the broken pieces of shattered hope and started reshaping the story in which they had hoped, had believed, had been destroyed. And at the end of those seven miles an extraordinary new vista emerged, a new hope, a greater hope, a hope that filled their hearts with burning. And then the bread is broken, and the burning bursts into sudden, blinding light. Now, at last, they know who they believe in...The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for the third Sunday of Easter (Year A).Poem: 'I saw him standing' translated from the Welsh of Ann Griffiths by Rowan WilliamsNT: Acts 2:14a, 36-41Gospel: Luke 24:13-35

How does one make any sense of that which is beyond comprehension? How does someone from a flat world grasp a third dimension? How do we estimate the cost of our darkness, the damage of our sin, both to ourselves and to the stardust of the cosmos of which we are formed, and from which all else is created? Are we arrogant to think that we even have such significance? And yet the story of the Incarnation requires us to understand that the Creator knows we do. How? Worse, for some unfathomable reason, the Creator considers us worth the ultimate sacrifice. Us, who are guilty of dust and sin. Why?We may think we know. And perhaps we can know enough, and that is enough.It is called Love.But the consequence of his coming is beyond our wildest imaginings. All that terrifies us evaporates as the mist in the morning sun. The clouds break open and the sudden shaft of sunlight reveals the brightest of fields. Eternity has inrupted our time-delimited existence. There is no more need for violence or greed, for insecurity or fear, for domination and manipulation, for the quest for power or wealth or freedom; all the trappings of a death-infested world. The Dawn of a new world has woken and we are invited to tread in his wake. The painting has come to Life.The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for Easter Morning, 2023.Poem: 'Love (3)' by George HerbertNT: Acts 10:34-43Gospel: Matt 28:1-10

Sometimes we struggle with the concept of 'belief'. Yet everything we do from the moment we get up to the moment we die is governed by what we believe about the world we inhabit. The stories we are told by the society in which we live have the power to control our concept of reality, and hence the entire direction of our lives, simply because we 'believe' them.So when Jesus says to Martha, 'do you believe?', he is challenging the story by which she lives, the story that defines her understanding of what is real. 'I am the resurrection and the life. Do you believe me?' And then the Spirit blows, and breath comes to the dry bones. Our reality cracks, splits, shatters, and Life flows in. So the soil that we are learns how to Breathe once again.The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for the Fifth Sunday of Lent, Year APoem: 'The Desert Speaks' by Cynthia FullerOT: Ezek 37:1-14NT: Rom 8:6-11Gospel: John 11:1-45

A loose woman and a single man meet alone at a well in the desert. He starts talking about giving her 'living water'. This is the sort of place where encounters of a certain type begin.John's Gospel is the gospel of the Spirit. Jesus has been speaking to Nicodemus about the Spirit blowing beyond the boundaries. How far beyond? This is the first woman we encounter in John's Gospel after his mother. Not only is she a woman, but worse, she's a Samaritan. And although the conversation begins enigmatically, Jesus turns a key and unlocks her to open to the Spirit. John is showing us how Jesus pushes the boundaries, not just beyond Mount Gerazim of the Samaritans, but beyond the Temple of Jerusalem. He has replaced the Temple as the meeting place of God, and the Anointed Agent of the Spirit of God. The living waters of the Holy Spirit in the Sinai desert flow from him who is the rock and the manna, Jesus, the bread of heaven. This is heady stuff.And the work of the Spirit? To restore us to the likeness of God - to love the world unconditionally, just like him who gave his Son to bring us home.The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for the Third Sunday of Lent (Year A).Poem: 'I am the Great Sun' by Charles CausleyOT: Ex 17:1-7NT: Rom 5:1-11Gospel: John 4:5-42

"And he shall be known in the breaking of the bread." He, the Bread."Did not our hearts burn within us as he talked to us?" Yet still they did not recognise him.I wonder how often that has happened to us? This ancient Gaelic Rune of Hospitality comes from the west Highlands of Scotland:I saw a stranger yesterday.

I put food in the eating place -

Drink in the drinking place -

Music in the listening place -

And in the blessed name of the Triune

He blessed myself and my house,

My cattle and my dear ones.

And the lark said in her song,

Often, often, often goes the Christ

in the stranger's guise.

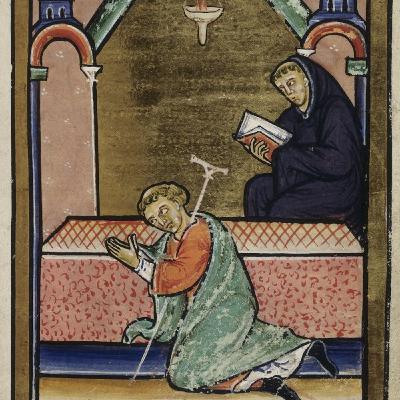

Our final reading from Bede's Life of Cuthbert. We discover, surely with a smile on Bede's face, that Cuthbert was a useless builder, and the repairs made by Aethilwald, his successor on Farne, weren't much better. Bede is circumspect about Cuthbert's involvement in this last miracle; indeed, he is always careful, in every account, to ensure we understand that it is God who performs the miracle. The saints in heaven are merely the ones interceding on our behalf. Here we see the Church, of which Cuthbert was but a part, continuing, working, and praying. And, as Bede says in his closing sentence, "Almighty God, in this present age, is wont to heal many, and, in time to come, will heal all our diseases of mind and body; for he satisfies our desire with good things, and crowns us for ever with lovingkindness and tender mercies."

The Resurrection.It’s different in each of the Gospels. In Luke, Mary Magdalene and a group of at least four other women go to the tomb, enter it, and meet two angels, but no Jesus. In Matthew, two women, Mary Magdalene and another Mary, go to the tomb, experience an earthquake and meet a single angel sitting on the stone that used to seal the tomb, who invites them to go in and have a look. Then they meet Jesus on the way back. In Mark, three women reach the empty tomb, enter and find a single angel sitting at one end, and run away, terrified. In John’s Gospel, Mary Magdalene goes alone, finds the tomb empty, runs to tell Simon Peter and John, returns behind them, and after they’ve gone, the angels turn up and she then meets Jesus, mistaking him for the Gardener.The utter confusion of what actually happened is the most compelling evidence that it actually did. How could it be any other way? Who remembers the details? Who was there? What was the order of events that morning? How many angels? Were there angels? The stone was rolled away! The tomb was empty! It was THE LORD!!! Nothing else matters. He is risen! Shock. Disbelief. No. It cannot be. It's impossible. Yes, I know he said it, but he didn't mean this. Did he?The trees in the painting begin to move in the wind. Clothes on the static figures ripple in the breeze. Colours start to shift and change, as the painting comes to life, like the picture on the wall in chapter one of CS Lewis' 'Voyage of the Dawntreader.' We are treading a new dawn into a new world. This is the 8th Day. The painter has arisen.A young man develops paralysis that spreads from his feet, progressively moving upwards through his body, which weakens daily, causing him to struggle to breathe, until he is completely paralysed, able to move only his mouth. Sounds like Guillain-Barré syndrome, and in extreme cases patients need ventilation. After a few weeks or months patients usually start a gradual improvement, and within a year most people have fully recovered.In this case, however, Cuthbert's shoes are taken from his coffin and placed on the lad's feet. His breathing instantly improves and he falls into a calm sleep. Those keeping watch over him that night observe the healing taking place, noticing first one, and then the other leg twitching. By the time of Lauds, in the early hours of the morning, he had regained sufficient strength to join the brethren in the chapel, standing for the whole service. This is no ordinary recovery. Extraordinary.

Wind. Breath. Spirit. All the same word. A Pharisee, a son of Abraham, is in the dark, visiting the rabbi by night. What is this wind? What is this birth of which you speak? But we are sons of Abraham. Aren't we? The wild wind of God has blown beyond the boundaries. So how do you know where it blows to? The death of water and the birth of wind. St John the Evangelist is in his element.The Bewcastle Benefice sermon for the Second Sunday of Lent (Year A).Poem: 'Instructions for the Desert' by Cynthia FullerOT: Gen 12:1-4aNT: Rom 4:1-5,13-17Gospel: John 3:1-17

The Crucifixion.Begun with the visit of the angel to a young lass in Nazareth who said 'yes', the Incarnation of the composer into his composition culminates with this climactic moment. The cosmos cracks and fissures as the Temple curtain is rent in two. Red dwarfs shudder and black holes expirate across a billion trillion galaxies. The composer dies. The colossal terror of unheard dis-chord shatters the silence of icy darkness. The fabric of the space-time continuum ruptures, collapsing in to single point of historical particularity as spirit and matter are united in the agony of a moment of utter isolation. My God, my God, why have you forsaken me. All words end in silence. There is nothing that human speech can offer. The unbearable weight of darkness has descended. This is the nature of sin.Matter and spirit are inseparable. The Creator breathed life into the soil. Cuthbert is dead, has been dead for over a decade, yet his body still retains a connection with his spirit while awaiting resurrection. In a similar way to an icon, it acts as a conduit between the material and spiritual worlds. Cuthbert is present, and can be greeted and talked to as a member of the same body of Christ. Like any fellow Christian, he can be asked to intercede on our behalf, 'would you pray for me?' This is what the clergyman of Bishop Willibrord Clement believed, what all the early church believed across the world. It seems his belief was vindicated and his request effective.

A sorry tale of politics, power, and crowd rule, or is that otherwise known as democracy, with 'social influencers' doing their piece? Three times Pilate says he will release Jesus, three times he is beaten back by the increasing vehemence of the crowds. Of course, he could have called in the army to crush the rising riot, but it would not have helped his thankless task of trying to govern this brittle people. Capitulation. We may speak of miscarriages of justice, but the deep irony of it is, as Jesus already knew, our redemption could not have happened any other way. How could the Creator heal his own lover, other than by absorbing into himself the bitterness, violence, anger, insecurity, pride, arrogance, greed, and every other human darkness, all of which can ultimately be traced back to the terror of facing death and annihilation. Jesus' passion and death is the ultimate Passover.Cuthbert is barely mentioned in today's short reading. Instead, we hear of Eadberht, bishop of Lindisfarne, who sang his paean of Cuthbert in yesterday's chapter, becoming progressively more ill and dying. The Anglo-Saxon saints, along with the rest of the early Church, had a completely different view of Christian suffering to us. For them, pain and illness, although not to be sought, was participation in the suffering of Christ on the Cross, carrying their cross as Jesus commanded, in order to bring healing back into the world. A quick or sudden death, therefore, cheated them out of this privilege, meaning that they were somehow found to be unworthy of sharing in Christ’s work. The granting of Eadberht’s wish, to die through a ‘long and wearing illness’, gave him the right to be buried close to Cuthbert’s uncorrupted body, as he, too, had been found worthy of sharing in Christ’s redeeming work. Bede's final comment says it all: 'the very clothes worn by [Cuthbert], both in life and in death, have still the power to heal.' Eadberht has found his healing.