Discover Monteverdi and his constellation

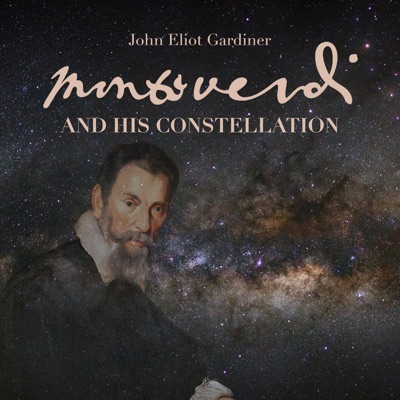

Monteverdi and his constellation

Monteverdi and his constellation

Author: Monteverdi Choir & Orchestras

Subscribed: 88Played: 715Subscribe

Share

© The Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras Limited

Description

John Eliot Gardiner, Founder and Artistic Director of the Monteverdi Choir & Orchestras, presents eight podcasts that explore Monteverdi's role at the centre of seismic shifts and tumultuous advances in all the arts and sciences during the early 1600s, spearheaded by his contemporaries - Galileo, Kepler, Bacon, Shakespeare, Caravaggio and Rubens.

With the help of specially recorded musical illustrations and a handpicked team of experts, Gardiner guides listeners through an in-depth investigation into the development of the early-modern mind.

With the help of specially recorded musical illustrations and a handpicked team of experts, Gardiner guides listeners through an in-depth investigation into the development of the early-modern mind.

8 Episodes

Reverse

The year 1600 was the start of a century of unprecedented change, of extraordinary invention and of tumultuous advances in all the sciences and the art forms. For some it was a time of optimism and expanding horizons, while for others it was deeply unsettling. This introductory podcast lays the foundation for viewing the period through the lens of seven prominent thinkers, mathematicians and artists. John Eliot Gardiner makes a strong case for Monteverdi to be seen as a significant 'star' in a constellation of innovative talent that also included Galileo, Rubens, Caravaggio, Kepler, Shakespeare and Francis Bacon.

A meeting of far-flung minds and a vigorous exchange of ideas occurred more frequently in these years than at any time hitherto. The paths of Galileo, Rubens, and Monteverdi crossed at the Gonzaga court in Mantua in March 1604. What might they have talked about and what can we learn about the interconnectedness of science and the arts at this time?

Bacon's formulation of the inductive method - the study of the empirical fact of antecedents and consequences - gave voice to the scientific advances being made by Galileo and Kepler in the face of widespread incredulity, opposition and persecution. The mind of Europe was now poised for a new venture of thought by this exceptional generation, one dominated by mathematics and physics but paralleled by striking developments in the arts.

Music can help us to grasp the true modernity of this enormous shift in human consciousness. Monteverdi's first opera, L'Orfeo (1607), is almost a manifesto for the power of music now elevated to a level of virtuoso craftsmanship and universal human emotion far beyond anything previously attained or experienced - an example of what Stephen Sondheim describes as "skill in the service of passion." Monteverdi was mapping out a new terrain for music, capable henceforth of pursuing a life if its own - a fresh vision which would dominate composition for ever afterwards. John Eliot Gardiner guides listeners through two centuries of musical and poetic evolution which laid the foundations for this remarkable achievement.

The young star chosen and coached by Monteverdi to sing the title role in his second opera, Arianna, died of smallpox just days before the scheduled première in 1608. Her replacement, an experienced singing actress, held strong views on the character of the abandoned heroine, Ariadne. This podcast explores how women suddenly step forward as creative participants and instigators in this brave new world of the senses. Monteverdi showed a particular empathy with his female protagonists and performers. Actress Dame Janet Suzman finds a resonant truthfulness in Shakespeare's Cleopatra, and we hear how the painter Artemisia Gentileschi dealt with her real-life experience of rape and processed it in her creative work. A window of opportunity opened for women artists and musicians in this period, allowing a temporary escape from paternalistic dominance, before closing again by mid-century.

Visual art – and especially the work of Caravaggio and Rubens (in different but complementary ways) now aimed to intensify sensory experience and drama. What Monteverdi called the "natural path to imitation" was a radical bid to represent, magnify and even 'improve' upon nature through song and music theatre. The Church was not alone in finding this secularisation of knowledge alarming. Even the contemporary French philosopher Montaigne noted "Our mind is an erratic, dangerous and heedless tool. It is hard to impose order and moderation upon it".

The focus here is on the growing awareness of the physical, mental and psychological attributes of the individual, and the development of a new philosophy which leads ultimately to Descartes' formulation: cogito ergo sum. A growing awareness of the physical, mental and psychological attributes of the individual leads to a fresh focus on the 'common man' - notably by Shakespeare, but also in their own ways by Caravaggio and by Monteverdi. Spoken theatre and opera are parallel vehicles for expressing and dramatising the human condition and the fluctuations and depths of the human heart. The first public opera house opens in Venice in 1637. Monteverdi, now maestro di cappella at the Basilica of St Mark, is perfectly placed for one final, extraordinary push into this brand-new dramatic world.

Monteverdi's swan-song, L'incoronazione di Poppea (1643),is a high-water mark of the new genre of public opera, Shakespearean in its contrasts of high and low-life characters, political chicanery and outrageous theatricality. It coincides with the death of the last two in this constellation of genius - Galileo in 1642 and Monteverdi a year later - and marks the end of this extraordinary period of innovation that shaped the modern world. Their demise coincides with incipient European economic upheavals and warfare and, meteorologically, the start of a mini ice age. Pressures to re-establish moral order took hold, and the old hierarchy governed by reason was regaining ground in reaction to the cultivation of the individual artistic pursuit of creativity and originality.