Discover Oddly Influenced

Oddly Influenced

55 Episodes

Reverse

An elaboration on episode 49's description of the brain as a prediction engine, focusing on a theory of what emotions are, how they're learned, and how emotional experiences are constructed. Emotions like anger and fear turn out to be not that different from concepts like money or bicycle, except that the brain attends more to internal sensations than to external perceptions. If the predictive brain theory is true, the brain is stranger than we imagine; perhaps stranger than we can imagine. Main sourcesLisa Feldman Barrett, "The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization," Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2017.Lisa Feldman Barrett, How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain, 2017.Andy Clark, The Experience Machine: How Our Minds Predict and Shape Reality, 2024.Other sources"... Chemero’s approach in his book Radical Embodied Cognitive Science (episode 43)...""... Clark suggests something like this in his 1997 book, Being There, covered in the unnumbered episode just before episode 41...""... Remember how, last episode, I distinctly remember driving seated on the left side of the car while in Ireland..."George A Miller, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing Information,” 1956. ("... replicating an experiment from 1949...")CreditsPicture of the University of Illinois Auditorium is from Vince Smith and is licensed CC BY 2.0. It was cropped.

Memories appear to be constructed by plugging together stored templates. Do concepts operate the same way?SourcesSuzi Travis, "False Memories are Exactly What You Need", 2024.Lisa Feldman Barrett, "The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization," Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2017.CreditsImage of street warning from Dublin, Ireland, via Flickr user tunnelblick. Licensed Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic.

We see a creature near us, and we describe it as a dog. Why that and not "mammal" or "animal"? And if that dog's a Springer Spaniel, and we know it's a Springer Spaniel, why do we nevertheless call it a "dog"? In an apparent digression, I discuss the idea in cognitive science of a "basic level of categorization" (or abstraction). While we construct hierarchies and taxonomies, we tend to operate at one specific level: one that's not too abstract and not too concrete. SourcesGeorge Lakoff, Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind, 1987.Gregory L. Murphy, The Big Book of Concepts, 2002.Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2024. CreditsThe image of the dog and cat is via https://fondosymas.blogspot.com. It is licensed as Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 3.0 España.

It's fairly pointless to analyze metaphors in isolation. They're used in a cumulative way as part of real or imagined conversations. That meshes with a newish way of understanding the brain: as largely a prediction engine. If that's true, what would it mean for metaphorical names in code?Sources* Lisa Feldman Barrett, "The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization," Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2017. (I also read her How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain (2017) but found the lack of detail frustrating.)* Andy Clark, Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again, 1997. CreditsImage of a glider under tow from zenithair.net.

When we name a class name `Invoice`, are we communicating or thinking metaphorically? I used to think we were; now I think we aren't. This episode explains one reason: ordinary conversation frequently uses multiple metaphors when talking about some concept. Sometimes we even mix inconsistent or contradictory metaphors within the same sentence. That's not the way we use metaphorical names in programming.SourcesLakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 1980. (I worked from the first edition; there is a second edition I haven't read.)Andy Clark, Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again, 1997. Lisa Feldman Barrett, "The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization," Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2017.CreditsPicture of cats-eye marbles from Bulbapedia, the community-driven Pokémon encyclopedia.

In 1970, Winston W. Royce published a paper “Managing the Development of Large Software Systems.” Later authors cited it as the justification for what had come to be called the "waterfall process." Yet Royce had quite specifically described that process as one that is "simplistic" and "invites failure."That's weird. People not only promoted a process Royce had said was inadequate, they cited him as their justification. And they ignored all the elaborations that he said would make the inadequate process adequate. What's up with that? In this episode, I blame metaphor and the perverse affordances of diagrams.I also suggest ways you might use metaphors and node-and-arrow diagrams in a way that avoids Royce's horrible fate.In addition to the usual transcript, there's also a Wiki version.Other sourcesLakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 1980.Laurent Bossavit, The Leprechauns of Software Engineering, 2014.George A Miller, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing Information,” 1956.CreditsDawn Marick for the picture of the fish ladder. Used with permission.

Conceptual metaphor is a theory in cognitive science that claims understanding and problem-solving often (but not always) happen via systems of metaphor. I present the case for it, and also expand on the theory in the light of previous episodes on ecological and embodied cognition. This episode is theory. The next episode will cover practice.This is the beginning of a series roughly organized around ways of discovering where your thinking has gone astray, with an undercurrent of how techniques of literary criticism might be applied to software documents (including code). Books I drew uponAndrew Ortony (ed.), Metaphor and Thought (2/e), 1993 (four essays in particular: see the transcript).Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, 1980. (I worked from the first edition; there is a second edition I haven't read.)Two of the Metaphor and Thought essays have PDFified photocopies available:Reddy's "The Conduit Metaphor – A Case of Frame Conflict in Our Language About Language"Lakoff's "The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor"Other things I referred toHelper T cellsRichard P. Gabriel's website"Dead" metaphorsThe history of "balls to the wall"CreditsThe image of an old throttle assembly is due to WordOrigins.org.

In this episode, I ask the question: what would a software design style inspired by ecological and embodied cognition be like? I sketch some tentative ideas. I plan to explore this further at nh.oddly-influenced.dev, a blog that will document an app I'm beginning to write. In my implementation, I plan to use Erlang-style "processes" (actors) as the core building block. Many software design heuristics are (implicitly) intended to avoid turning the app into a Big Ball of Mud. Evolution is not "interested" in the future, but rather in how to add new behaviors while minimizing their metabolic cost. That's similar to, but not the same as, "Big O" efficiency, perhaps because the constant factors dominate.The question I'd like to explore is: what would be a design style that accommodates both my need to have a feeling of intellectual control and looks toward biological plausibility to make design, refactoring, and structuring decisions?SourcesAndy Clark, Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again, 1997Ray Naylor, The Mountain in the Sea, 2022Erlang processes (explained using Elixir syntax)MentionedBrian Foote and Joseph Yoder, "Big Ball of Mud", 1999TetrisIllinoisNew HampshirePrior workWhat I'm wanting to do is something like what the more extreme of the Extreme Programmers did. I'm thinking of Keith Braithwaite’s “test-driven design as if you meant it” (also, also, also) or Corey Haines’s “Global Day of Code Retreat” exercises (also). I mentioned those in early versions of this episode's script. They got cut, but I feel bad that I didn't acknowledge prior work. CreditsThe image is an Ophanim. These entities (note the eyes) were seen by the prophet Ezekiel. They are popularly considered to be angels or something like them, and they're why the phrase "wheels within wheels" is popular. I used the phrase when describing neural activation patterns that are nested within other patterns. The image was retrieved from Wikimedia Commons and was created by user RootOfAllLight, CC BY-SA 4.0.

In the '80s, David Chapman and Phil Agre were doing work within AI that was very compatible with the ecological and embodied cognition approach I've been describing. They produced a program, Pengi, that played a video game well enough (given the technology of the time) even though it had nothing like an internal representation of the game board and barely any persistent state at all. In this interview, David describes the source of their crazy ideas and how Pengi worked.Pengi is more radically minimalist than what I've been thinking of as ecologically-inspired software design, so it makes a good introduction to the next episode. SourcesPhilip E. Agre, Computation and Human Experience, 1997, contains a description of Pengi, but is much more about the motivation behind it and also a discussion of "critical technical practice" that I think is nicely compatible with Schön's "reflective practice". I intend to cover both eventually. Philip E. Agre and David Chapman, "Pengi: An implementation of a theory of activity", 1987Chapman linksMeaningness.com (including greatest hits)I found his ideas about Vajrayana Buddhism intriguingOtherA recording of a Pengo gameThe foundational text of ethnomethodology is notoriously (and, some – waves – think, gratuitously) opaque. I found Heritage's Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology far more readable. I've enjoyed the Em does Ca (conversational analysis) Youtube series. The episode on turn-construction units hits me where I live. She talks about how people know when, in a conversation, they're allowed to talk. I'm mildly bad at that in person. I'm somewhat worse when talking to a single person over video. I'm horrible at it when on a multiple-person conference call, with or without postage-stamp-sized video images of faces. CreditsThe Pengo image is by Arcade Addiction. Retrieved from Wikipedia. Fair use.

Scientists studying ecological and embodied cognition try to use algorithms as little as they can. Instead, they favor dynamical systems, typically represented as a set of equations that share variables in a way that is somewhat looplike: component A changes, which changes component B, which changes component A, and so on. Peculiarities of behavior can be explained as such systems reaching stable states. This episode describes two sets of equations that predict surprising properties of what seems to be intelligent behavior.Source:Anthony Chemero, Radical Embodied Cognitive Science, 2011Either mentioned or came this close to being mentionedJames Clerk Maxwell, "On Governors", 1868 (PDF)Andy Clark, Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again, 1997Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "Embodied Cognition", 2020Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "The Computational Theory of Mind", 2021Wikipedia, "Dynamical Systems Theory"Nick Bostrom, "Letter from Utopia", 2008/20CreditsThe image is from Maxwell's "On Governors", showing the sort of equations "EEs" work with instead of code.

Suppose you believed that the ecological/embodied cognitive scientists of last episode had a better grasp on cognition than does our habitual position that the brain is a computer, passively perceiving the environment, then directing the body to perform steps in calculated plans. If so, technical practices like test-driven design, refactoring in response to "code smells," and the early-this-century fad for physical 3x5 cards might make more sense. I explain how. I also sketch how people might use such ideas when designing their workplace and workflow. Books I drew uponAndy Clark, Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again, 1997Alva Noë, Action in Perception, 2005Also mentionedGary Klein, Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions, 1998I mentioned a session of the Simple Design and Test conference.The sociology book I contributed to: The Mangle in Practice: Science, Society, and Becoming, 2009, edited by Andrew Pickering and Keith Guzik. My chapter, "A Manglish Way of Working: Agile Software Development", is inexplicably available without a paywall.The MIT AI Lab Jargon FileI believe the original publication about CRC cards is Kent Beck and Ward Cunningham, "A laboratory for teaching object oriented thinking", 1989. I also believe the first book-type description was in Rebecca Wirfs-Brock et. al., Designing Object-Oriented Software, 1990. The idea of "flow" was first popularized in Mihály Csíkszentmihályi's 1990 Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. The idea of the hedgehog and the fox was popularized by Isaiah Berlin in his 1953 book The Hedgehog and the Fox (a wikipedia link).The original developer of the Pomodoro technique describes it here. There was a book about it, but Goodreads has been sufficiently enshittified that I can't find it. Perhaps you might be interested in Reduce PTSD and Depression Symptoms in 21 Days Using the Pomodoro Method instead? Because Goodreads prefers that.The Boy Who Cried World (wikipedia)CreditsI was helped by Steve Doubleday, Ron Jeffries, and Ted M. Young. I took the picture of Dawn in the tango close embrace.

Embodied or Ecological Cognition is an offshoot of cognitive science that rejects or minimizes one of its axioms: that the computer is a good analogy for the brain. That is, that the brain receives inputs from the senses; computes with that input as well as with goals, plans, and stored representations of the world; issues instructions to the body; and GOTO PERCEPTION. The offshoot gives a larger causal role to the environment and the body, and a lesser role to the brain. Why store instructions in the brain if the arrangement of body-in-environment can be used to make it automatic?This episode contains explanations of fairly unintelligent behavior. Using them, I fancifully extract five design rules that a designer-of-animals might have used. In the next episode, I'll apply those rules to workplace and process design. In the final episode, I'll address what the offshoot has to say about more intelligent behavior.SourcesLouise Barrett, Beyond the Brain: How Body and Environment Shape Animal and Human Minds, 2011Anthony Chemero, Radical Embodied Cognitive Science, 2011Andy Clark, Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again, 1997Mentioned or relevantPassive Walking Robot Propelled By Its Own Weight (Youtube video)Steven Levy, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, 1984Guy Steele, "How to Think About Parallel Programming – Not!", Strange Loop 2010. The first 26 minutes describe programs he wrote in the early 1970s. Ed Nather, "The Story of Mel, a Real Programmer", 1983. (I incorrectly called this "the story of Ed" in the episode.)Ed Yong, An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us, 2022Andrew D. Wilson, "Prospective Control I: The Outfielder Problem" (blog post), 2011CreditsThe picture of a diving gannet is from the Busy Brains at Sea blog, and is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 Deed.

This excerpt from episode 40 contains material independent of that episode's topic (collaborative circles) that might be of interest to people who don't care about collaborative circles. It mostly discusses a claim, due to Andy Clark, that words are not labels for concepts. Rather, words come first and concepts accrete around them. As a resolute, concepts are messy. Which is fine, because they don't need to be tidy.SourcesLouise Barrett, Beyond the Brain: How Body and Environment Shape Animal and Human Minds, 2011Anthony Chemero, Radical Embodied Cognitive Science, 2011MentionedEmily Dickinson, "A narrow Fellow in the Grass", 1891 (I think version 2 is the original. Dickinson's punctuation was idiosyncratic, but early editions of her poetry conventionalized it.)Talking Heads, "Psycho Killer", 1977Andy Clark, Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again, 1997. (This is the source for much of the argument, but I'm relaying it second hand, from Barrett.)CreditsThe image titled "Girl seated in middle of room with books; smaller child standing on stool and wearing dunce cap" is via the US Library of Congress and has no restrictions on publication. It is half of a stereograph card, dating to 1908.

Software design patterns were derived from the work of architect Christopher Alexander, specifically his book A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. This excerpt (from episode 39) addresses a problem: most software people don't know one of Alexander's most important ideas, that of "forces". SourcesChristopher Alexander et al, A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, 1977.Mentioned (or that I wish I'd found a way to mention)Gamma et al, Design Patterns, 2004Eric Evans, Domain-Driven Design, 2003. I also like Joshua Kerievsky's pattern-language-like description of study groups, "Pools of Insight".Brian Marick, "Patterns failed. Why? Should we care?", 2017 (video and transcript)"Arches and Chains" (video) is a nice description of how arches work.Ryan Singer, "Designing with forces: How to apply Christopher Alexander in everyday work", 2010 (video)CreditsBy Anneli Salo - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikipedia Commons

The last in the series on collaborative circles. The creative roles in a collaborative circle, discussed with reference to both Christopher Alexander's forces and ideas from ecological and embodied cognition. Special emphasis on collaborative pairs.SourcesMichael P. Farrell, Collaborative Circles: Friendship Dynamics and Creative Work, 2001Louise Barrett, Beyond the Brain: How Body and Environment Shape Animal and Human Minds, 2011Anthony Chemero, Radical Embodied Cognitive Science, 2011MentionedEmily Dickinson, "A narrow Fellow in the Grass", 1891 (I think version 2 is the original. Dickinson's punctuation was idiosyncratic, but early editions of her poetry conventionalized it.)Talking Heads, "Psycho Killer", 1977Paul Karl Feyerabend, Killing Time: The Autobiography of Paul Feyerabend, 1995Michael J. Reddy, "The conduit metaphor: A case of frame conflict in our language about language", in A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and Thought, 1979 (wikipedia article)Ken Thompson, "Reflections on Trusting Trust" (Turing Award lecture), 1984CreditsThe picture of the umbrella or rotary clothesline is due to Pinterest user MJ Po. Don't tell Dawn it's the episode image.

Farrell describes a number of distinct roles important to the development of a collaborative circle. This episode is devoted to the roles important in the early stages, when the circle is primarily about finding out what it is they actually dislike about the status quo. In order to make the episode more "actionable", I describe the roles using Christopher Alexander's style of concentrating on opposing "forces" that need to be balanced, resolved, or accommodated. SourcesMichael P. Farrell, Collaborative Circles: Friendship Dynamics and Creative Work, 2001.Christopher Alexander et al, A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, 1977.Mentioned (or that I wish I'd found a way to mention)Gamma et al, Design Patterns, 2004Eric Evans, Domain-Driven Design, 2003. I also like Joshua Kerievsky's pattern-language-like description of study groups, "Pools of Insight".Brian Marick, "Patterns failed. Why? Should we care?", 2017 (video and transcript)"Arches and Chains" (video) is a nice description of how arches work.Ryan Singer, "Designing with forces: How to apply Christopher Alexander in everyday work", 2010 (video)"Rational Unified Process" (wikipedia)James Bach, “Enough About Process, What We Need Are Heroes”, IEEE Software, March 1995.Firesign Theatre, "I think we're all bozos on this bus", 1971. (wikipedia)"Bloomers" (wikipedia article about a style of dress associated with first-wave feminists).CreditsThe picture is of Dawn and me sitting on our "Stair Seat", where we observe the activity on our lawn, sidewalk, and street. Which mainly consists of birds, squirrels, and people walking dogs. But it still fits Christopher Alexander's pattern of that name.

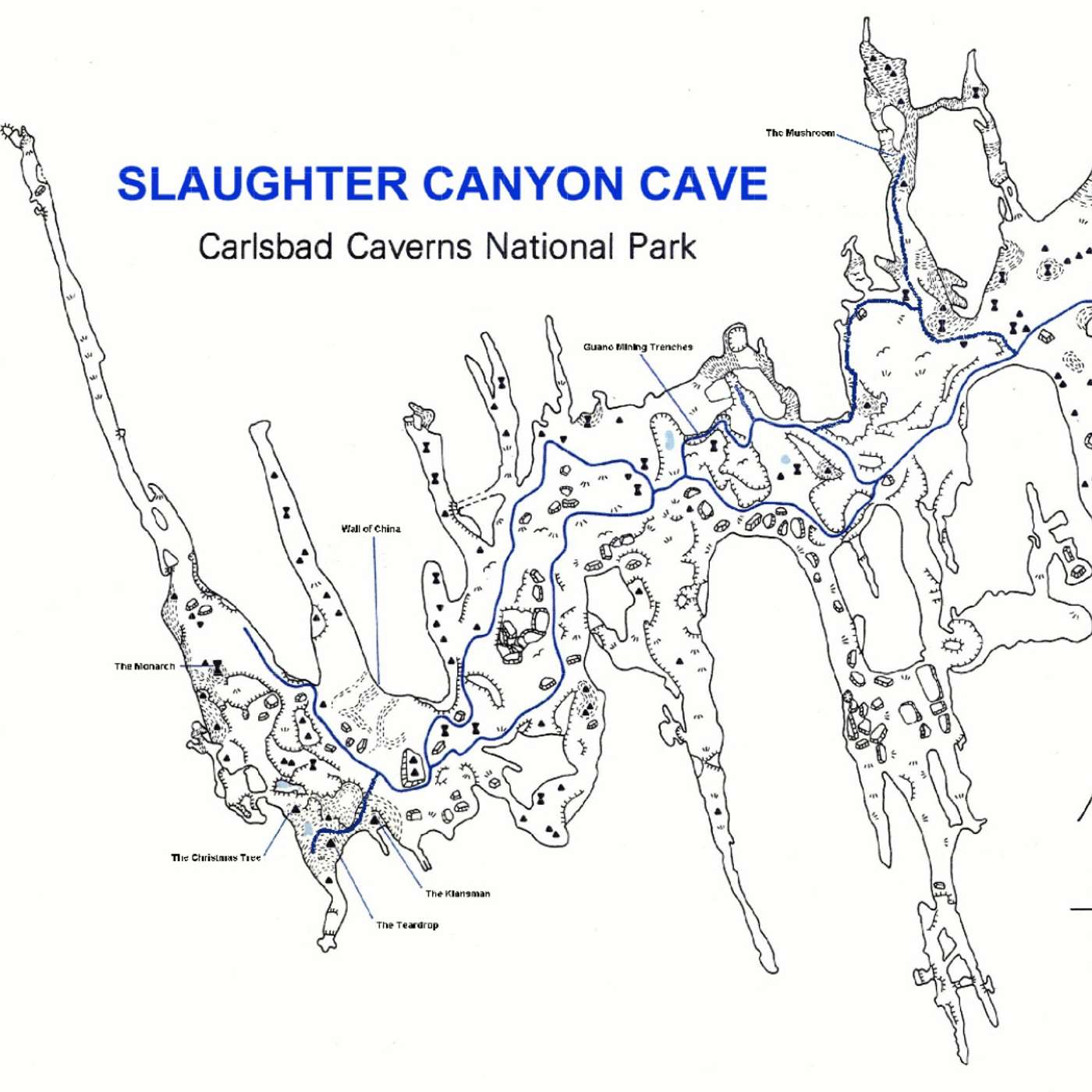

Collaborative circles don't have a smooth trajectory toward creative breakthrough. I describe the more common trajectory. I also do a little speculation on how a circle's "shared vision" consists of goals, habits, and "anti-trigger words." I also suggest that common notions of trust or psychological safety may not be fine-grained enough to understand circle-style creative breakthroughs.I continue to work from Michael P. Farrell, Collaborative Circles: Friendship Dynamics and Creative Work, 2001.Mentioned"Bright and dull cows"Sam Kaner, Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, 1996Brian Marick, "Seven Years Later: What the Agile Manifesto Left Out", 2008Image creditsThe image is of a route map for a particular cave complex in Carlsbad Caverns National Park, USA. There is not a nice linear path from the starting point to (any) destination. This is also true of creative work, like collaborative circles. The image is in the public domain.

An interview with Lorin Hochstein, resilience engineer and author. Our discussion was about how to handle a complex system that falls down hard and – especially – how to then prepare for the next incident. The discussion is anchored by David D. Woods' 2018 paper, “The Theory of Graceful Extensibility: Basic Rules that Govern Adaptive Systems”, which (in keeping with the theme of the podcast) focuses on a general topic, drawing more from emergency medicine than from software.Lorin HochsteinResilience engineering: Where do I start?WebsitePublicationsBlogTalksMentionedBrendan Green, "The Utilization, Saturation, and Errors (USE) method", 2012?How Knight Capital lost $500 million very quickly. Link and link.Lucy Tu for Scientific American, "Why Maternal Mortality Rates Are Getting Worse across the U.S.", 2023David Turner, A Passion for Tango: A thoughtful, Provocative and Useful Guide to that Universal Body Language, Argentine Tango, 2004 Fixation over fomites as the transmission mechanism for COVID: Why Did It Take So Long to Accept the Facts About Covid?, Zeynep Tufekci (may be paywalled)The safety podcast about a shipping company flying a spare empty airplane: PAPod 227 – What-A-Burger, Fedex, and Capacity, Todd Conklin, podcastCorrectionOn pushing, pulling, and balance, A Passion for Tango says on pp. 34-5: "The leader begins the couple's movement by transmitting to his follower his intention to move with his upper body; he begins to shift his axis. The follower, sensing the intention, first moves her free leg and keeps the presence of her upper body still with the leader. [...] The good leader gives a clear, unambiguous and thoughtfully-timed indication of what he wants the follower to do. The good follower listens to the music and chooses the time to move. The leader, having given the suggestion, waits for the follower to initiate her movement and then follows her." He further says (p. 34), "As a leader acting as a follower, you really learn quickly how nasty it feels if your leader pulls you about, pushes you in the back or fails to indicate clearly enough what he wants."Apologies. I was long ago entranced by the idea that walking is a sequence of "controlled falls". Which is true, but doesn't capture how walking is a sequence of artfully and smoothly controlled falls. Tango is that, raised to a higher power.CreditsThe episode image is from the cover of A Passion for Tango. The text describes the cover image as an example of a follower's "rapt concentration" that, in the episode, I called "the tango look".

I was a core member of what Farrell would call a collaborative circle: the four people who codified Context-Driven Testing. That makes me think I can supplement Farrell's account with what it feels like to be inside a circle. I try to be "actionable", not just some guy writing a memoir.My topics are: what the context-driven circle was reacting against; the nature of the reaction and the resulting shared vision; how geographically-distributed circles work (including the first-wave feminist Ultras and the Freud/Fleiss collaboration); two meeting formats you may want to copy; why I value shared techniques over shared vision; how circles develop a shared tone and stereotyped reactions, not just a shared vision; and, the nature of “going public” with the vision. MentionedMichael P. Farrell, Collaborative Circles: Friendship Dynamics and Creative Work, 2001.Cem Kaner, Jack Falk, and Hung Quoc Nguyen, Testing Computer Software, 1993.Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass), 1863.context-driven-testing.com (including the principles of context-driven testing), 2001?Cem Kaner, James Bach, Bret Pettichord, Lessons Learned in Software Testing: a Context-Driven Approach, 2002.Association for Software Testing.Elisabeth Hendrickson, Explore It! Reduce Risk and Increase Confidence with Exploratory Testing, 2012.Jonathan Bach, "Session-Based Test Management", 2000.Patrick O'Brian, Post Captain, 1972. (It's the second in a series that begins with Master and Commander.)Four articles that demonstrate personal style:James Bach, “Enough About Process, What We Need Are Heroes”, IEEE Software, March 1995.Brian Marick, "New Models for Test Development", 1999.Bret Pettichord, "Testers and Developers Think Differently", 2000.James Bach, "Explaining Testing to THEM", 2001.Los Altos Workshop on Software Testing and related:Cem Kaner, "Improving the Maintainability of Automated Test Suites", 1997. (This contains the conclusions of LAWST 1 as an appendix.)The LAWST Handbook (1999) and LAWST Format (1997?) describe the meeting format.The "Pattern Writers' Workshop" style is most fully explained in Richard P. Gabriel, Writers' Workshops & the Work of Making Things: Patterns, Poetry... (2002). James Coplien, "A Pattern Language for Writer's Workshops" (1997), describes writers' workshops in the "Alexandrian style" of pattern description (the one used in the seminal A Pattern Language). "Writers Workshop Guidelines" is a terse description.Image creditThe image is the painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe.

Michael P. Farrell's Collaborative Circles: Friendship Dynamics and Creative Work (2001) describes how groups of people follow a trajectory from vague dislike of the status quo, to a sharpened criticism of it, to a shared vision (and supporting techniques) intended to displace it. The development of so-called "lightweight processes" in the 1990s can be viewed through that lens. I drag in a little discussion of binary oppositions as used in Lévi-Strauss's Structural Anthropology (1963) and later work.MentionedThe first NATO Software Engineering Conference, 1968The SAGE air-defense networkDavid L. Parnas and Paul C. Clements, “A Rational Design Process: How and Why to Fake It”, 1986The Alphabet of Ben Sira. For the story of Lilith, see this episode of the Data Over Dogma podcast: "Lilith Unfair"Etymology of "sinister"Wulf Schiefenhövel, "Biased semantics for left and right in 50 Indo-European and non-Indo-European languages", 2013Edsger Dijkstra, "On anthropomorphism in science", 1985Edsger Dijkstra, "How do we tell truths that might hurt?", 1975 (enthusiastically)Philip J. Davis and Reuben Hersh, The Mathematical Experience, 1980Peter Adamson, "Plato's Phaedo" (podcast)John W. Tukey, Exploratory Data Analysis, 1977Kent Beck, Extreme Programming Explained: Embrace Change, 1999CreditThe image of the screech owl is by permission of Erica Henderson. It was inspired by the "Doamurder, West Virginia (The Book of Genesis, Part 1)" episode of the Apocrypals podcast. I bought my Lilith T-shirt from their merch store, which also contains sticker versions, etc.