Discover Storied: San Francisco

Storied: San Francisco

569 Episodes

Reverse

Listen in as my friend Vandor Hill and I wrap up his second year of Whack Donuts' brick-and-mortar location. This is Vandor's third appearance on Storied: SF. Here are the other two episode's we've done with him: Vandor Hill of Whack Donuts Whack Donuts' First Anniversary We recorded this podcast at Whack Donuts in Embarcadero 4 in December 2025. Photo by Jeff Hunt

In Part 2, we pick up right where we left off in Part 1. Continuing her history of 3117 16th Street, Lex notes that "The Roxie has lived many lifetimes." She describes the Eighties and Nineties as busy times for the theater. They ran a series of Werner Hertzog films in that era. Akira Kurisawa visited for some of his movies. Many local films and film festivals took place at The Roxie. Frameline was set there. San Francisco and the greater Bay Area were becoming something of a cinema mecca. The aforementioned Roxie Releasing ended up helping the business in times when ticket sales weren't so hot. Even then, the theater went through some really rough patches financially. That persisted into the early 2000s. And then, The New College came along. The Roxie became the school's film center, in fact. Hope emerged … until The New College lost its accreditation and had to shutter. In 2009, with a still-uncertain future ahead of it, The Roxie officially became a nonprofit, one of the first of its kind. It was a huge turning point for the theater—but it didn't solve all their problems. There were numerous "Save The Roxie" campaigns, and about 10 years ago or so, the Board contemplated closing down for good. Obviously, that didn't happen. But in 2020, like every person and business on the planet, The Roxie fell victim to the pandemic. Lex walks us through how COVID and the ensuing shutdown impacted the theater. In the years leading up to 2020, the theater was finally thriving again. But they were the first movie theater in San Francisco to shut down, which they did so voluntarily before the mandate. The Roxie stayed shuttered for 434 consecutive days during COVID. In that time, employees sent postcards to Roxie members; they did pop-up drive-in cinemas; they did "Virtual Roxie," in which the theater curated movies folks could watch from home; and they held online panel discussions with filmmakers. Once they felt it was safe and they reopened The Roxie, it all felt worth the sacrifices. Instantly, the theater was full of people and life and joy. Despite all that, though, financial struggles resumed once again. Eventually, as many businesses were able to do, they got back to full capacity movie screenings. The conversation shifts to The Roxie's ongoing efforts to buy the building it's situated in. Henry describes the process, which began with a feasibility study. The study came back in the affirmative—they had a real shot at raising the money needed for such a huge endeavor. He describes the current board members as a cohesive bunch. No factions exist and they all are aligned with laser-sharp focus. The next step was convincing the landlords to sell to them, to prove that the non-profit was capable of raising the kind of money it would take to get the deal done. That took about a year of back-and-forth. But after that process of negotiating with the building's previous owner, they had an asking price. They could then raise money. The first donations came from Roxie Board members. In fact, within two weeks of launching the capital campaign, every member of the Board had donated. Then many of those Board members began pitching … and pitching … and pitching. This April, the efforts went public, and to great success. The lovefest began. The goal from the outset was to raise $7 million in three years. As The Roxie approaches the end of the second year of its fundraising (meaning nowadays), it's within striking distance. Because the total amount that they're raising includes money for way overdue maintenance and upgrades, they already have enough for the basic purchase. In fact, the building is already under the ownership of The Roxie Theater nonprofit organization. Now that the goal is in sight, they're aiming to close 2025 with a final push to make it to $7 million in two years instead of three. And that's where you and I come in. If you or anyone you know would like to help a San Francisco landmark further cement its legacy in our city by buying its building, find more info and make a donation, please visit the Forever Roxie page. For donations of $30 and above, you will receive a Forever Roxie enamel pin. Donations of $60 and above receive the pin and a specially-designed pair of Roxie socks. For a donation of $120 and above, you receive all of the above along with a long-sleeve Roxie tee shirt. Also, from now through December 31, the Walter and Elise Haas fund will match every gift to the campaign. We end this episode with Lex reminding folks about The Roxie's weekly newsletter, which goes out every Wednesday and is always a delight. Go to roxie.com and click the "newsletter" button at the top-right to sign up.

When you tell friends you're going to see a movie at The Roxie, there's an almost palpable envy that sets in for them. In this episode, meet Lex Sloan and Henry S. Rosenthal. Lex is The Roxie's executive director and Henry is on its Board of Directors and the chair of the theater's capital campaign, which we'll get to. In the meantime, if you'd like to help keep a bona fide San Francisco landmark in its rightful home until the end of time (they'd sure love you to, and so would I), donate to the Forever Roxie fund here. We start with Henry, who lets us know that the "S" in his name stands for Sigmund. Henry was born in Cincinnati and had what he describes as an "idyllic childhood" there. He started going to music shows when he was 13, seeing bands like Iggy and the Stooges and MC5. After graduating from high school, he moved to San Francisco in 1973 to attend school at The New College of California. He was an early subscriber to Rolling Stone magazine, where he had seen a New College ad. That ad captivated young Henry's imagination. He visited the campus, which was in Sausalito at the time, after a road trip from Ohio to the West Coast. The school tried to get him to enroll right then, but Henry decided to go back home and finish high school first. Henry produced cable TV shows while in college. In a sense, it's what he's been doing ever since. When Henry moved to San Francisco, there were still operating movie palaces on Market. Before really making friends here, he'd spend a lot of time inside those theaters. It was the era of movies like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Enter the Dragon. He says it's difficult to put into words (it is), but San Francisco just grabbed him and never let go. Then we turn to Lex Sloan. Lex went to college in Bellingham, Washington, at the type of school that allows you to design your own degree, which she did. Lex got a bachelor's in "social change media," which is so on the nose, it tickles. Post-graduation, she went to what she calls "the middle of nowhere, Arizona," but that lasted all of seven or eight months. Looking for where to land next and being a spreadsheet nerd (like me), Lex made a list. And lo and behold, San Francisco checked the most boxes. She got a job in Redwood City, not knowing that that Peninsula town wasn't exactly The City. No matter—she landed. The job involved teaching video production at a community center. At first, she stayed in a hostel on Mission Street before finding a place all her own on Craigslist. That was 2005, and Lex hasn't looked back. We go back to Henry to hear the story of how The Roxie drew him in. Perhaps jokingly, he says he laments not visiting when The Roxie was a porn theater. Henry doesn't recall his actual first visit, but says he's been a regular since first learning about the place. He knew Bill Banning, who created Roxie Releases, the organization's distribution operation. (Rivers and Tides, the documentary about artist Andy Goldsworthy, is among their releases.) Banning and he were friends for a while. Their kids went to school together. Their lives kept intertwining, including at film festivals. When The Roxie transitioned to a nonprofit and created a board, folks like Bill invited Henry to join it. He politely refused … until the theater was on firmer ground financially. And once it was, he was in. Henry's goal in joining The Roxie board was singular, he says: To help the organization buy the building where the theater sits. Lex does remember her first time at The Roxie. After she landed in The City, she sought work on local film crews. She found a crew and their film (Getting Off) premiered at The Roxie during Frameline. Because she was "only" a production assistant, she wasn't comped a ticket. Lex remembers showing up and seeing a rather long and daunting line to get in. But! That line was filled with her people. She calls that screening "magical" and "electrifying." Over the years, she came back time and again, for one-off movies as well as for film festivals. When Lex worked for Frameline, one of her jobs was carrying film prints into the projection booth at The Roxie and other theaters. Fast-forward to 10 years or so ago, when Lex became operations director at The Roxie. We then turn to the history of The Roxie, with Lex as our tour guide. The space where the theater sits today was built to be just that—a movie theater. It wasn't converted at any point from something else to become a place where folks watch movies. The folks who run the theater today have discovered and held onto the original blueprints from 1913. Its first name was The Poppy Theater. Then it was The 16th Street. Then The New 16th Street, The Gaiety, The Rex, and finally, in the early 1930s, The Roxie. That oh-so-recognizable marquee came to The Mission from an auto dealership in Oakland aboard a barge that traveled across The Bay. A lot of the history of The Roxie before the Seventies is not well-known. But, after becoming The Roxie, it was first a German-language cinema (concessions at the time were German candies). Thanks to some projectionist's notes they've found, they know that in the Fifties, it became a variety space of sorts. In the late Sixties/early Seventies, it was an XXX theater, as mentioned in Henry's story earlier. In those days, a turnstile out front kept underage folks and those who didn't pay out (or did it?). In 1976 or '77, a group of local artists took over. That group changed a lot of things. It became more of an arthouse cinema, as it remains to this day. The folks who ran the place put people before profits. Midnight movies became a thing The Roxie was known for. Check back Thursday for Part 2 with Lex and Henry. We recorded this podcast at The Roxie in The Mission in October 2025. Photography by Jeff Hunt

Listen in as I join Erin and Ange of Bitch Talk to chat with H.P. Mendoza about all things Mission District. We wax poetic about H.P.'s home hood, spinning yarns about the infamous neighborhoo'd's past, present, and future. We recorded this podcast at Zeitgeist in (duh) The Mission in November 2025. Photo by Wally Gobetz

In Part 2, we pick up more or less where we left off in Part 1, hearing the story of how Randall and Al came to love all things neon. Their enthusiasm kicked into high gear when they started noticing neon signs coming down, and they decided to try to do something about it. That something started with documenting the signs. And with that came a bit of a learning curve, especially around photographing artificial lights at night. Over the next five years, they captured and captured and captured, getting as many extant signs as they could find. Randall had some book design experience under her belt, especially aspects like packaging and getting it to a printer. She also knew how to put a book proposal together, and so they did. But friends and people in the publishing industry warned them that it would difficult to find a publisher. Randall suggested to her partner that they publish the 200-page book themselves, and that's exactly what they did. They had the photos and the design down. All they needed was money. Kickstarter was still pretty new, and they chose that platform. Within two weeks, they had met and exceeded their goal. It was on. Donations came in from all over The City, the country, and the world. In addition to money to fund publication, Randall and Al were gifted a community of fellow neon enthusiasts. These days, many folks in that community attend symposiums that Al and Randall put on. I ask the couple to name other towns, besides San Francisco, that have what I'm calling "good neon." They rattle off a few—Denver; Portland, OR; Livingston, MT; Reno; Los Angeles. Randall plugged a site by Debra Jane Seltzer called RoadsideArchitecture.com that documents neon and other signage in all US states except Hawaii and Alaska. To help design the cover of their book, Randall and Al asked their Instagram followers. A photo of the Verdi Club and its neon won, easily. That venue quickly emerged as the obvious choice for where to host the book's launch party. Around 300 guests showed up that night in 2014. After launch, they realized they needed ideas to keep the book and The City's neon signage in people's minds. Tours were among the first of those ideas. But that started as a one-off in Chinatown. A few of the guests on that first tour were tube benders—folks who, among other things, bend the glass that goes into making a neon sign. In the end, the students taught the teachers that day. Those tube benders introduced Randall and Al to a guy in Oakland named Jim Rizzo who does neon restoration work at Neon Works. They've been working with Jim ever since. When I ask if that Chinatown tour in support of their book was what got them started doing tours in general, Randall turns back to The Society for Experiential Graphic Design (SEGD). The group was holding its convention in San Francisco and asked Randall and Al to take visitors on a tour of The City. They learned a lot from that, including how long to hold your tour before folks get tired or hungry. Fast-forward to after their book was published, when folks who bought the book reached out asking if Randall and Al could show them around San Francisco's various noteworthy neon signs. They didn't think they had it in them to do that on a regular basis. But then other San Francisco tour guides signed up wanting to be shown our city's neon. Little by little, those guides taught Randall and Al tools of the trade. In the beginning, they second-guessed themselves. "We're a photographer and a graphic designer. What are we doing giving tours?" But they soon learned the real value of neon walking tours—the chance to walk around San Francisco at twilight with people from all walks of life. The side hustle was its own reward (something very familiar to me, in my role hosting this podcast). If you'd like to take one (or all) of Randall and Al's tours, sign up on their website—SFneon.org. You'll also find other books about neon that they've published. One of those books is all about saving neon. They got in touch with folks they were meeting from all over the country who were doing that work in their own cities. The book is a good resource for anyone who, like Randall and Al in the Mission all those years ago, wants to preserve signs in their area. So, they published the book, started doing tours, launched an annual conference … but still, they wanted to do more. They talked with folks at SF Heritage, picking their brains for things like how to get grant money for neon sign preservation. They told them to talk with people at The Tenderloin Museum (TLM), and mentioned Katie Conry specifically. When Randall and Al talked with her, Katie just got it, immediately. TLM has been SF Neon's fiscal sponsor ever since. (Ed. note: This podcast was arranged with help with Katie at Tenderloin Museum. Thanks, Katie!) As you learned on this show back in April of this year, TLM is expanding. Part of that expansion will free up the museum's current space. Once they move all of their exhibits and artifacts into the new space, the current Tenderloin Museum will become a San Francisco neon gallery. Randall and Al are of course a huge part of that work. The first sign donated to the new gallery is from Tony's Cable Car, a spot near and dear to my heart and just blocks from my home. We end the podcast with Randall reminding folks that this time of year is best for the kinds of tours they do. It gets dark earlier, so there are more hours in the day to see neon signs in their glory, and the hours start around 4:30/5 p.m.

The story of how Randall Ann Homan got her name is a unique one. In this episode, meet and get to know Randall and her partner, in life and in neon, Al Barna. Today, the couple are all about all things San Francisco neon. But we'll get to that. When Randall's dad was a teenager, he saved a young girl named Randall from drowning. After saving the little girl, he taught her to swim. Years later, when he had his own daughter, he carried the name forward. Randall Homan grew up in Goodyear, Arizona, just outside of Phoenix. The town was named for the tire company, and it was where, back in the day, the eponymous blimp lived when not in use. Randall has a fun story about being brushed by the Goodyear blimp's ropes when she was a kid. She considered her hometown "Nowheresville" and left as soon as she could—at 17, after graduating from high school early. Randall came straight to San Francisco to attend Lone Mountain College (the University of San Francisco today). "It was wild," she says about her time in the Seventies in The City. Art school is what brought both Randall and Al to San Francisco. At her school, there was a dorm where all the art students, including Randall, lived. Views out the window of that dorm were always completely foggy except for one thing—the neon sign at the Bridge Theater on Geary pierced that blanket of gray. It left a strong impression on them both. Rewinding a bit, Randall says that there was a little neon in her hometown of Goodyear, and she was fascinated by it. She was interested in how it worked, but also was drawn to the beauty of the colored light. When I ask Randall whether she ever left San Francisco after her initial move here, she rewinds a little bit to talk about how young they both were when she and Al met. "Cupid hit us both square in the heart," she says. But they wanted to see the rest of the country. They both wanted to visit where the other is from (Al came here from Pennsylvania), but they compromised on New Orleans. They were drawn to NOLA by the music, and they sure did see a lot of that. But getting jobs was a different story. That didn't come easy in "the Big Easy," and so they came back. They've been in their San Francisco apartment for 30-plus years, and they're not going anywhere. As mentioned, Al comes from Pennsylvania, specifically the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre northeast area of the state. It was coal country, but young Al wanted to pursue art. And so he came to The City to go to the San Francisco Art Institute (RIP). It was 1976, and even though he was in college, Al never intended to stay longer than a year or two. The Beats influenced Al, and though San Francisco figures largely in their history, so does travel. But he and Randall were here during the so-called Season of the Witch—1978. Randall is quick to point out how much easier it was to move within The City back then, something they did every six months or so for a stretch. I ask them to rattle off the different neighborhoods, and they oblige me: Lower Nob Hill, North Beach, and The Mission figure prominently, among others. Al goes into a little more detail about how the two met. It was at a going-away party for a mutual friend. For him, that first meeting settled it. Randall was about to go to school in Los Angeles, and Al decided to join her down south. After a couple years at SFAI, Al left school to work for a film company, where he did a lot more learning. He was taking lots of photos, and it wasn't until Randall pointed out the abundance of neon signs in the backgrounds of his pictures that Al picked up on it. In addition to LA, they also spent some time in Flagstaff, Arizona, where they both got jobs at a silk screen company. Randall also got a job working for a sign painter whose hands were too shaky for his craft. The work she did painting signs left a big impression on Randall, and you can see it in her love of old neon signs today. Between the Eighties and early 2000s, they each worked in their respective crafts—photography for Al, and graphic design for Randall. Al worked for several decades for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (the parent org for the de Young and Legion of Honor museums). He shares a story of helping prevent a bomb from exploding at the old de Young museum building, just before it was scheduled to be demolished anyway. Randall's graphic design work had her, among other jobs, designing album covers for bands. She did show posters, logos, and branding—work she still engages in to this day. In the Nineties, she designed the cover page for one of the Bay Guardian Best of The Bay issues. Eventually, the two decided to create a book all about neon. Putting together that first book—San Francisco Neon: Survivors and Lost Icons—took five years. We'll talk in more depth about that and their other, more recent projects in Part 2. We end Part 1 with the story of how neon became the central focus of both Al's and Randall's lives. It involved a sign in the Mission that was there one day and gone the next. Check back Thursday for Part 2 with Randall and Al. We recorded this podcast at Mario's Bohemian Cigar Store in North Beach in November 2025. Photography by Nate Oliveira

In Part 2, we pick up where we left off in Part 1, with that fateful visit Saikat took to The Mission. He and friends worked a lot, but didn't have a lot of money (sound familiar?). To learn The City and have some fun, they signed up for as many walking tours as they could find. After a few months living in Park Merced, Saikat relocated to The Mission—16th and Hoff, specifically. Esta Noche was nearby, and it's where he saw his first drag show. A buddy worked with Saikat to build a web wireframing tool (think the basics of web design, the skeleton of sites, so to speak). They knew some other folks in tech, naturally, and met the people who were launching Stripe, an e-payments then in startup mode. Stripe eventually hired Saikat and his friend. Saikat was the fledgling company's second engineer. He started to see tech as a force for social good, but that didn't really jell well with the work he did for Stripe. And so he quit a couple years in. The woman he was dating at the time (whom he later married) still lived in New York, and Saikat visited as often as he could. He didn't yet consider himself political, but he was thinking about issues, specifically income inequality, poverty, and climate change. In early 2015, Bernie Sanders announced his run for president in the 2016 election. Saikat hadn't heard of Sanders at that point, but he was addressing those very issues that had become important to Saikat. He signed up to be a Bernie volunteer and started on a sub-Reddit called "Coders for Sanders." But Saikat wanted "in" in. And so he got in touch with someone working on the campaign. That someone was Zack Exley, whose political biography runs deep. Exley's job with the Sanders campaign at the time Saikat got in touch was to organize all the volunteers wanting to work for Bernie but who didn't live in the first four primary states (Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina). That effort needed tech solutions, which Saikat brought. But they weren't hiring technologists at the time. Still, Exley "snuck" him on as an organizer. He expected the experience not to be a big deal. He'd work for about a year, maybe learn a thing or two. But the Bernie 2016 campaign had other ideas. "We were on the brink of actually doing these big, structural changes," he says of his time on the campaign. Coming out of that experience, he and other organizers decided to take what they had learned and start applying it to folks running for Congress, starting with the 2018 midterms. Initially, they called their effort "Brand-New Congress," and the goal was to recruit 400 people nationwide to run for office. They fell far short of that ambition, managing to get around a dozen folks to run. They wanted people from all walks of life, not just lawyers, which Congress was and is made up of primarily. And they got that, just not on the scale they had hoped. The group became Justice Democrats, which is still in existence today. They didn't have the money to spend heavily on most of their candidates, so they went all-in on someone named Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez out of The Bronx. Her brother had nominated her as part of Brand-New Congress, and Saikat had gotten to know her through the process. He saw early on what a powerful candidate she was. He moved to NYC to help run AOC's first bid for Congress as a co-campaign manager. She won, of course, and Saikat had a front-row seat for AOC's ascendancy to the national stage. He says she was her authentic self through it all. Saikat helped start a think tank coming out of the Sanders campaign as well, developing many policy positions and ideas, among them what came to be known as the Green New Deal. It was a policy platform as much as anything else. It called for a renewed and very much intensified effort to combat climate change while also creating and upgrading infrastructure. They approached every candidate running for president in 2020 asking them to sign on to a Green New Deal pledge. They all eventually did. (Biden's "Build Back Better" platform was essentially a version of the Green New Deal.) Around this same time, Saikat had signed on to be AOC's chief of staff. But Ocasio-Cortez wanted him to be her insider-type guy (I bring up Veep because, well, duh), and Saikat politely refused. He offered to help her staff up and get good people in place instead. By April 2019, having got the Green New Deal launched, so to speak, he let her know that he'd be leaving that summer, around the time his daughter was expected. That September, Saikat moved back to San Francisco. One of the first things he did was rejoin think tanks and work on filling out gaps in the Green New Deal. The pandemic hit and he dug his heels in on policy. By the time the 2024 election approached, they were ready to hand something to Kamala Harris if she were to win. Obviously, that didn't happen. He believed those who warned that a Trump victory had bad implications for democracy. But then he watched his own rep in DC, Nancy Pelosi, shrug the 2024 loss off in a "You win some, you lose some" way. He launched his campaign for that seat in Congress "by tweet" in February 2025. Turning from the national to the local, I ask Saikat what San Francisco issues are top of mind for him. He starts with the idea of meeting with and listening to San Franciscans, his would-be constituents: town halls, office hours, mass Zoom meetings … he's already doing a lot of that work. Saikat believes that to begin to effectively address issues at the local level—ICE kidnappings, healthcare, housing, transit—big changes are needed nationally. The California primary election takes place on June 2, 2026. The candidates who come in first and second place in that election will go on to compete in the Midterm election next November. To learn more and get involved, head to Saikat's website—saikat.us. Follow the campaign on Instagram and Threads.

The story of Saikat Chakrabarti begins in a time when his parents' and ancestors' country was being torn apart, almost literally. In this episode, meet and get to know Saikat. These days, he's busy knocking on doors and otherwise hitting the ground in a bid to represent San Francisco in the US Congress. As I write this, just last week, Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi announced that she would not run for a 20th term. Timing! Let's go back to mid-Nineteenth Century India. Because his dad's family is Hindu, they were forced to relocate after Indian/Pakistani partition, fleeing their home country of Bangladesh for Kolkata (Calcutta) in India. Folks had warned Saikat's grandfather, a school teacher, to leave, and they did. Once in Kolkata, his grandfather opened a school largely for the kids of other refugees living in the area. Owing to the school's success, he was able to secure a one-bedroom apartment for his family of 12—he, his wife (Saikat's grandmother), and 10 kids, including Saikat's father. Saikat has been back to that apartment. He says that, walking around that neighborhood all these years later, folks still recognize his dad, Samir, thanks to what his grandfather did for them and their family. His mom, Sima, had it better than his dad. But still, she went to a school with dirt floors. Saikat looks to his ancestors' struggles—the communities they were part of, and how those communities came together to address issues the government neglected—for inspiration today. When his dad was young, a friend took him to an office where he was pitched to come to the United States. There was a whole set-up. The sell was simply the so-called American Dream. Saikat's parents met in India through an arrangement. Their respective parents knew someone who set it all up. They met and got married about a week later in a field. The visa his dad had applied for at that office came through after he'd been married, making it a bigger decision than it would've been if he were still single. He was also the primary earner in his own family, and they didn't want him to leave. He decided to take that leap regardless. His dad showed up in the US with $8 in his pocket and no job yet secured. He slept on a friends' couch in Manhattan and hit the pavement, résumé in hand. And it worked. He got a job. Saikat's dad had studied civil engineering in college. His first job in his new country was with a company that built skyscrapers … NYC skyscrapers. It was 1979. Saikat's mom came to join her husband soon after, and they had their first kid, Saikat's older sister, Urmi, while living in Queens. His dad and his mom also experienced their first cold-weather winter that year. After a stint in New York, Samir moved his family to Pittsburgh. He had visited there in the summer, liked it, got a job offer, but relocated in the winter. Once again, the weather got the better of the young family. Seeking a warmer climate, they moved to Texas, first to Houston, and then to Fort Worth. At this point in the podcast, I decided to do something I've never done in the eight years since Storied: San Francisco began. And that's because I've never had any guests on the show who are from where I'm from. I chose to dork out with Saikat about my hometown. Thank you for indulging us (me, really). The first question I had for Saikat is: What hospital were you born in? Harris Methodist. Holy shit, same! He asked me my age (52), what schools I went to (Bruce Shulkey Elementary, Wedgwood Middle School [Saikat went there for one year], and Southwest High School). What a fun turn on this podcast, me rattling off the schools I went to like born-and-raised San Franciscans do. Heh. I digress into a sidebar about the race riot that happened at my high school during my junior year. You'll have to listen, or you can read a little more about it here. Then we get to hear about Saikat's experience growing up in the same city. His family lived in a suburb (apparently not far from where my parents still live), and he describes his early life as fairly standard—hanging out with friends, going to the mall (the same mall I was a regular at a decade or so before). But, being an Indian-American, Saikat experienced racism I was privileged enough to avoid. Saikat makes a distinction, though, between intentional, malicious racism and what I'd call accidental or unintentional racism. It's an important distinction, and he says most of what he experienced in Fort Worth was the less-harmful variety. He summarizes his childhood thusly—family, school, the Bengali-American community in Fort Worth. One member of that community, Saikat's best friend from childhood, lives downstairs from him in San Francisco today. His whole world in high school was, as Saikat puts it: hip-hop, basketball, and math. He got into Harvard, which he says he didn't expect. Many of his friends went to UT Austin (my alma mater), and he figured he'd go there, too. But he wasn't about to pass up the opportunity to attend one of the most highly regarded universities in the country. But Harvard was a culture shock for Saikat. The Fort Worth community he'd known all his life was working- and middle-class. The student body at Harvard was largely kids who came from money and had wildly different interests than he did. Saikat went into his shell his freshman year. As he emerged from that shell, he found his people at Harvard. In 2007, Saikat graduated from Harvard with a degree in computer science. He'd spent a summer in San Francisco between his junior and senior years, and loved it. All his life, The City had been presented as this place where "cool shit happened." Movies, music, TV shows, skateboarding, the LGBTQIA and civil rights movements … and of course, the fledgling internet. Tech and social justice—both existed in a cutting-edge environment here. He lived in New York City for one year immediately after he graduated. We riff on life in NYC vs. life here, agreeing on most aspects. When it was time for Saikat to find a new place to live, San Francisco was the obvious choice. The woman he was dating (his wife and mother of his child today) went to school at Cornell in Ithaca, New York, where he visited often. But even her friends told Saikat that he was much more a NorCal-type. Unable to find housing anywhere else in SF, Saikat first landed in Park Merced. He was happy to have a San Francisco address, but didn't feel like he was living in The City. A trip to The Mission changed that quickly. Check back Thursday for Part 2 with Saikat. We recorded this podcast at Duboce Park Cafe in October 2025. Photography by Jeff Hunt

Listen in as I chat with SFFILM's Soph Schultz Rocha and Keith Zwolfer all about this year's Schools at Doc Stories program, which runs Nov. 6–10. Learn more about this year's film festival at SFFILM's website. We recorded this podcast at SFFILM's Filmhouse in South of Market in October 2025.

In Part 2, we pick up where we left off in Part 1. Ian and I talk about how big baseball was in his life in his high school and early college years. He was a left-handed pitcher, which made him attractive to coaches. By the time he transferred to UC Berkeley, though, sports receded and academics took over. He played what's called club ball, which Ian explains is something between varsity high school-level and community college. At Berkeley, Ian majored in renewable energy, a topic that shows up in the art he does today. He minored in education, something that shows up in his coaching of kids these days. He lived in Berkeley while going to school there, and speaks to that experience. Ian moved back to The City after he graduated, in 2014. But, as he puts it, since then, he's "left and come back many times." First was Seattle for a summer. Then Portland for a year and a half. We go on a bit of a sidebar after I offer up my opinion that some folks in the Pacific Northwest can come across as friendly, but they can also be rather passive-aggressive. After Portland was New York City, where Ian lived for half a year. Then Nashville for three months. And after that, he got into a teaching program in Madrid, Spain, which I express my jealousy of. (Barcelona is one of my favorite places on Earth.) He was in Madrid right as the COVID pandemic hit, in fact. The teaching program he was in allowed him plenty of downtime—he worked essentially four days a week, four hours per day. And a lot of that time on his hands was filled with a rediscovery of doing art. His plan had been to leave at the end of a school year, and that happened to coincide with the onset of COVID. His return to his hometown, and his time here since 2020, has been spent trying to do art full-time. And that's where Ian's and my life intersect. It happened one day in the very location where we recorded this podcast: 540 Bar. Break Fake Rules was born when Ian lived in Spain. It started with stickers. He handed them out—to friends, to strangers. He came up with the phrase and liked it, among other reasons, for its openendedness. He feels "Break Fake Rules" requires participation, something he sees as going against the way technology is leading us. But BFR isn't the only artistic endeavor in Ian's life. Ian does a lot of collage work. Lately, he's been cutting up vinyl from discarded billboard signs. He'd tried working with paper and glue to make murals, but the elements always got the better of his outdoor art. Old billboard vinyl is the solution he's been looking for. Those of you who follow Storied:SF on Instagram might have recently noticed a few collaboration reels between us and Break Fake Rules. Ian approached me a couple months ago about being on a series he produces called "People Should Know," where someone—an artist, a small-business owner, a podcaster—comes on and speaks with a fencing-masked interviewer to talk about what they do and what folks should know about what they do. You can check out full-length videos of everyone who's been on People Should Know on the Break Fake Rules website. It was a lot of fun to do, so thanks, Ian! In asking Ian to let people know how to find him, we decided to start off with our favorite platform—in real life! He's currently selling furniture at Stuff by Luxe. He's got Break Fake Rules stuff there, too, as well as some of his 2D and 3D art. His website is BreakFakeRules.com. Find @breakfakerules and his personal account, @ianglues, on Instagram.

Listen in as I chat with Tommy Leyva, who has been decorating the fuck out of his home on Divisadero for nearly 20 years. Whether you're able to drop by, now or until a few days after Halloween, check out the video below the photos on this page. Follow Tommy and the Divisadero Halloween House on Instagram @divisaderohalloweenhouse. We recorded this podcast at the Divisadero Halloween House in October 2025. Photos and video by Jeff Hunt

This one starts out a little differently. Ian Paratore was born and raised in San Francisco, but he's moving away. This week. To Oakland. Ian's dad, Vince Paratore, moved into a Victorian in The Haight in the late-Seventies/early Eighties, and is still there. That's the house Ian grew up in starting roughly 10 years later. Both of his parents are artists and teachers. His dad came to San Francisco from Syracuse, New York, to study photography at SF State. And his mom, Valerie O'Riordan, is from Long Beach in Southern California. She moved to The City to work with ACT (American Conservatory Theater). The house at Page and Clayton is the only place Ian's dad has lived in SF. I asked Ian whether he knows any stories from that house before he was born in the early Nineties. Both his parents being "natural hosts," there were many parties. Nowadays, when his dad is out of town, Ian will sometimes have parties of his own at his dad's place. When he does, he says his dad often offers up stories from back in the day. One involves a party with so many people already inside cramming a hallway, folks had to come and go via the first escape. Back in the day, his dad was a general manager at restaurants like Stars, Donatello, Garibaldi's, and Beach Chalet, which he helped open. Both his parents were big in the San Francisco restaurant scene. We turn to Ian's early life, which he experienced in the mid-Nineties to early 2000s. As a kid, and a kid without a backyard, he spent a lot of time in Golden Gate Park and The Panhandle. He hung out on playgrounds and basketball courts. He adds that "the craziness of Haight Street was just … normal." I ask Ian about Skates on Haight, which I knew from my Eighties/Nineties skateboarding days from ads in magazines like Thrasher. (Marcella, who took photos for this episode and was with us at the table, chimes in at this point.) Ian rattles off some spots from his childhood in The Haight—places like Gus's before it was known as Gus's, an Ethiopian restaurant, and a musical instrument store. In high school, Ian got into visual arts and playing sports—mainly baseball and basketball. By the time he got to college, he played baseball "at a high level," and art fell more or less by the wayside. More on that in Part 2. But during high school, though he took art classes, sports dominated his life. We end Part 1 with Ian rattling off the San Francisco schools he went to. He did a stint at College of San Mateo (CSM) before getting into UC Berkeley, which was the first time he lived outside his childhood home. He had flirted with college on the East Coast before deciding to stay closer to home. Check back Thursday for Part 2 with Ian. And join us tomorrow for a very special, timely bonus episode. Follow Ian and Break Fake Rules on Instagram. We recorded this podcast at 540 Bar in the Inner Richmond in October 2025. Photography by Marcella Sanchez

In Part 2, we pick up where we left off in Part 1. It was 2010, and seeing that guy with the broken guitar on Risa's next visit to SF was the nail in the coffin, so to speak. She was moving here. One of her friends who already lived here found a spot in The Sunset for her. She packed up a car and drove north with her dad. She didn't necessarily have a plan back then, but Risa and I share how The City just got both of us and hasn't let go. Risa tells the story of how her parents moved to Japan briefly when she was 18. She asked her mom, "So, why did you come back (to California)?" And her mom told her (paraphrasing), "Because you wouldn't be able to do what you're doing there, you wouldn't have the same opportunities." It further affirmed for Risa her decision to move to San Francisco and pursue art. I ask Risa to catch us up on the last 15 years of her life. Generally speaking, she's been working to find her voice as an artist. She got into letterpress-printing, which she did for more than 10 years. She started a company with a friend and worked there for three years before branching out on her own. Doing so wasn't easy, but in hindsight, it made Risa stronger. She talks about a specific strain of misogyny that presented itself to women printmakers as well as how Risa handled that nonsense. That solo venture started off as a stationery company. She reached back to childhood memories, of a time when she witnessed letters coming to her mom from Japan as well her mom's messages back to her homeland. Risa saw those as lifelines to her mom's people back home, and wanted to preserve those memories and emotions and help others to do the same. Papallama was born. Before we talk about another fun thing Risa is up to, I need to express my newish-found love for 540 Bar on Clement. It's where Risa holds monthly "Drink and Draw" events, and it's quickly become one of my new favorite spots in The City. Risa started her monthly art events at the bar in 2022. The idea came from her letterpress days, when she'd do frequent "Letter-Writing Saturdays." She told her friend Leejay, one of 540's owners, about it, and they decided to bring that same idea to the bar. Shortly after they hatched the plan, though, Risa's dad passed away. The first drink and draw was a month later, and so many of Risa's friends turned out for her. What started out as every second Thursday of the month now takes place at 540 Bar on the third Thursdays of every month. Risa speaks in a little more detail of the care and intention she puts into her Drink and Draw events. For me, it's an extension of her art as well as her love of community. But it's also just her being a good host. The next Drink and Draw takes place the same day that this podcast drops—October 16, 2025. See ya there! The conversation shifts to Risa talking about taking part in our Every Kinda People show at Mini Bar. And we end the podcast with Risa sharing all the ways to find her, both online and in real life. Follow her on Instagram @risa_iwasaki_culbertson. Her website is risaculbertson.com. Photography by Jeff Hunt

Risa Iwasaki Culbertson was born in Japan. In this episode, meet and get to know Risa, one of the 12 artists in Every Kinda People, our group show at Mini Bar. Please join us this Sunday, Oct. 19, from 4–7 p.m. at Mini Bar for our Closing Party happy hour. Some of the artists will be on hand, as will friendly bartenders and me (Jeff). Back to Risa, though. Her mom is Japanese and her dad is from Ventura County in Southern California. Risa spent her first five or six years in Japan before her parents moved to California. She has memories of life in Japan before they moved. And after the move, Risa often went back to visit her grandmother. Risa says that, as a kid, she loved going back and forth between two very different cultures Her dad was in the military, which is what brought him to Japan, where he met his wife. Risa is their only child, something she and I go on a bit of a sidebar about. I'm not an only child, but I've met and befriended my fair share of well-adjusted only children. Hell, I married one. Risa found creativity early, and ran with it. Her parents were older, and being half-American, half-Japanese, she didn't feel like she fully belonged in either culture. Risa might've gotten her creativity from her mom, who did pottery, quilting, and other artistic things. Her dad was "a mad scientist of sorts," she says. He was into taking things apart and repurposing found objects. In Southern California, Risa spent time with other Hapa kids. Her mom was part of a large Japanese community, and there were plenty of mixed-race kids among that group. She's very much a product of the Eighties and Nineties and Southern California. She remembers the beginning of grunge and flannels. Risa remembers vividly when Kurt Cobain died (1994). Middle school for her happened in Orange County. Risa did hula dancing and tap dancing for many years, always while also painting and drawing. In high school, her art teacher was switched out and replaced with a nun who told the kids they couldn't use black inks. It felt to young Risa like too religious of a message, and it instilled in her an attitude of not wanting anyone to tell her what she can and cannot do with her art. She never took another art class. She was also something of a social butterfly in her high school years. Risa had different friend groups and in hindsight, feels like they were constantly getting together and doing things. Then we turn to what got Risa out of Southern California. One friend she met in college moved back to San Francisco, and another friend from down south wanted to move here. She visited The City and remembers sitting in a cafe talking to strangers. She felt then and there that the friendliness was right for her, and something she wasn't getting in Orange County. I share a quick story of being in Orange County and getting phone directions to a bar. Unbeknownst to me and my friends that night, the map put us on a highway … on foot. Yep. We rewind a little to chat about Risa's time in college. She always wanted to be at least art-adjacent, and so she took classes on manufacturing and even calculus. Thing is, she ended up liking calculus. Earlier in life, she sold stuff she made through catalogs she also created. That early entrepreneurship informed some business classes she later took in college, including business law. It all lead to Risa's getting a business degree. Right away, she started recognizing a disconnect between art and business. Back to her first impression of San Francisco, that day in that Haight Street cafe made The City feel like a place where she could get to know people. Risa shares a story that happened right before her move here. It involves a man boarding a BART train she and her friends were on. He had a broken guitar. They'd made googly eyes at each other, but she and her friends were too scared to talk with him. When he got off the train, he looked back and waved. Risa figured she'd never see this guy again. Three months later, she was back to visit her friend who lived here. She'd thought about him, but figured there was no way to actually find him. Then, as you can guess, it happened. Risa says she's still friends with that guy to this day. Check back Thursday for Part 2 with Risa, which includes the story of her move to San Francisco. We recorded this podcast at Risa's studio in the Inner Richmond in August 2025. Photography by Jeff Hunt

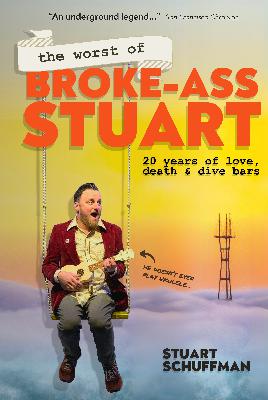

Listen in as I chat with Broke-Ass Stuart about, well, a lot of stuff. But we also talk about Stuart's new book, The Worst of Broke-Ass Stuart: 20 Years of Love, Death, and Dive Bars. The book is available at your favorite local indie bookstore and also at Bookshop.org. And get very affordable tickets for next Friday's (Oct. 17, 2025) book-launch party at Kilowatt here. We recorded this podcast at Emperor Norton's Boozeland in September 2025. Photos of Stuart by Jeff Hunt

In Part 2, we pick up where we left off in Part 1. To get us caught up to what Lisa is doing these days, we go back to her arrival in The Bay. Her work at the prop shop led to some other jobs, but competition was fierce and she sought a way to integrate art into the labor she undertook. She found it when the production of James and the Giant Peach hired her to do puppet fabrication. The work took place in a warehouse in South of Market and it wasn't quite as glamorous as people think. In fact, it was grueling, but rewarding. Her boss on that job was a woman named Kat. That was 30 years ago, and the two are good friends today. In fact, Kat is shooting a documentary about Lisa's incredible life called Made of Iron. More on that below. Lisa wanted to stick with animation, but was never able to get an art director job. She considered moving to LA, but shut that down pretty quickly. And so she decided to learn a trade—something her dad did back in the day. She went to a job fair and asked what the hardest trade represented there that day was. Lisa's trade became ironwork. Her introduction to the folks who did ironwork was a little rough. She was required to visit job sites and get an ironworker to sponsor her. It took her six months to get hired. She met a guy named Danny Prince who helped her get work in The City making precasts (think parking garages). She'd work during the week and go to classes for ironworking on Saturdays. Ironwork has, quite possibly since its inception, been very much a "man's" world. Lisa ran head-first into bigotry, prejudice, and discrimination from the get-go. But a combination of her own drive and the advice of a few mentors helped her get through it. There might have even been some "Go fuck yourself"s along the way, too. That said, the highs were high and the lows were low. "I never cried on the job," Lisa told me. But the tears would come once she was home in the evenings. Still, she persevered, and things got better and better for her. One of her early favorite jobs was on the then-new California Academy of Sciences. Besides it just being a really cool building, Lisa got to do many different jobs all around the place. She says it was incredible watching it all come together. Another job highlight was Lisa's work on the arena that came to be known as Chase Center (and for Valkyries fans, "Ballhalla"). Photos of Lisa helping build Chase can be seen in the gallery to the left here. Another was Marin General Hospital. And then there was the Golden Gate Bridge. After Chase Center and another, lesser job (and a divorce), Lisa got offered a job working on the Suicide Deterrent Net on my favorite bridge. But it wasn't just any job. She would be foreperson. She didn't think she could do it because she didn't know bridge work (despite working a little on the new Bay Bridge). After being told it was foreperson or nothing, she decided to take the job. Of course the crew she would oversee comprised all bridge-work veterans. Her approach was to be respectful of that. And her crew respected her back for it. The job entails taking out old pieces and beefing up the infrastructure of the bridge, which was finished back in 1933. Lisa talks at some length about a societal need for us all to have more respect for labor. I'm with her 100 percent. There's a lot that we take for granted every day, all over the place. Many people worked and still do work hard as hell so that we can have shit like roads and sidewalks, transit tunnels, housing, and so much more. We should recognize and respect that work. We end the episode with Lisa's thoughts about life, her work, and what she loves about San Francisco and the Bay Area. You can donate to help fund Kat's documentary at the Made of Iron website. And follow that adventure on Instagram @madeofirondocumentary.

Lisa Davidson is an ironworker with Local 377 San Francisco. Her team currently does ironwork on the Golden Gate Bridge. But we'll get to that. In this episode, S8 E3, meet and get to know Lisa. I first did that back in May at our Keep It Local art show at Babylon Burning (thanks, Mike and Judy!). Someone at the party that night approached me to let me know that there was a person there who works on the best bridge in the world (fact) and that I should meet them. I love when people really get me. Right away, I was drawn in by Lisa's warmth, charm, and sense of humor. And so we sat down outside in Fort Mason in early August and Lisa shared her life story. She was raised feeling like she had complete freedom. It was something Lisa didn't realize at the time, but looking back, it became clear to her. She was raised in Framingham, Massachusetts, just outside of Boston, in a liberal household. Her grandparents lived in Boston itself, and she loved visiting them when she was a kid. Her grandfather ran a tchotchke store in town called House of Hurwitz, and Lisa says that the place had a big influence on her outlook. It was located on the edge of what they call, to this day, the "Combat Zone" (think: red-light district). Her "wheelin' and dealin'" grandpa sold mylar balloons to the Boston Gardens for events held there. He told young Lisa that she could blow up balloons and that that could be her future. Lisa has a brother four years younger than she is. Her dad was an electrician. One of his clients was a lithograph press in Boston. He'd sometimes get paged for a job and have to leave his family, although Lisa now wonders whether he just wanted to get away from time to time. When she was a senior in high school, her parents divorced, despite being a very loving couple up to that point. She says her mom was "crazy in an I Love Lucy way. She was raised in the Fifties the way many young women at that time were, in a way that did its best to stifle any creativity. Suffice to say that her mom had fun decorating the house Lisa grew up in. Despite her and her family's Jewishness, Lisa revolted and wanted to go to Catholic school or just become a preppy L.L. Bean-type kid. She of course regrets rejecting the norms of her family nowadays. It was what it was. The family was more culturally Jewish than religious, though, something Lisa says was a huge influence on who she's become as an adult. She graduated high school and went to college at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. It wasn't Ivy League, but it was (and is) something of a preppy school. Where Lisa grew up, there was an expectation that kids would go to college, and so she went. It wasn't super far from home, but it wasn't close either. Her parents did suggest that Lisa maybe go to art school. But in her family, it was the kid dismissing that idea. "That's a not real school," young Lisa told them. She liked sports. At Amherst, she joined the crew team. She liked the competition and how good of shape it got you in. She liked it, but it was a lot of pressure. She graduated, took a year off working odd jobs, then dove into art school. So next up was Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). She was surprised she got in, and even navigated a bit of impostor syndrome. Surprised by the school's acceptance of her and feeling somewhat intimidated by other artist students, Lisa ended up doing printmaking. Rather than aiming for a master's degree, she sought a second bachelor's. Her studies had her spending a lot of time in the school's foundry, where she discovered welding. She loved it. During her time back in Amherst, she'd heard of a guy who was going to Alaska. (Lisa and I go off-topic into our shared distaste for camping at this point in the conversation.) Back to the Alaska story, her mom was fully supportive and even took her shopping at an Army Navy store. She went there and worked in canneries through the summer between her junior and senior years at Amherst. While she was up north, doing jobs all over the state, she met folks from California. From the stories they told her, it became a place she wanted to go. But first, RISD. In Rhode Island, she met a guy from Danville in the East Bay. When his family learned of her interest in our state, they invited Lisa to spend a summer with them, which she did. And she and her friend came to The City as often as they could. After those few months, she knew that California—and specifically, The Bay—was for her. She needed to go back and finish that second round of college in Rhode Island, and she did. After that, Lisa "beelined it" back to Oakland. She found work in a prop shop making sculptures out of foam with a chainsaw. Check back this Thursday for Part 2 with Lisa Davidson. We recorded this podcast at Equator Coffee in Fort Mason in August 2025. Photography by Jeff Hunt

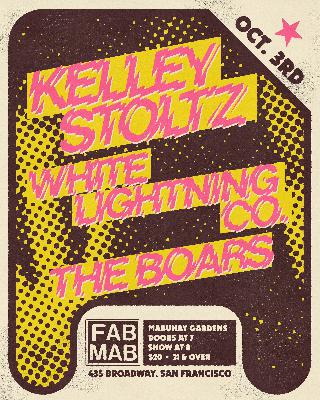

Listen in as I chat with Joanna Lioce all about the new Mabuhay Gardens. Joanna is booking monthly shows in the new legendary North Beach punk venue through the end of the year. Get tickets for the Oct. 3, 2025, Mabuhay Gardens show featuring Kelley Stoltz, White Lightning (PDX), and The Boars at EventBrite. We recorded this podcast at Vesuvio Café in September 2025.

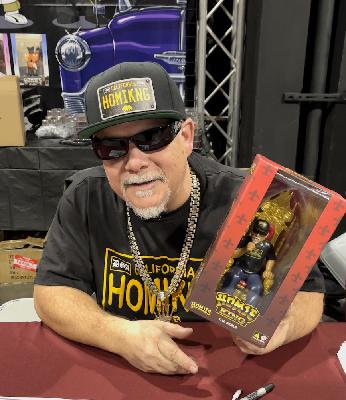

Listen in as I chat with David Gonzales, creator of Homies and this year's San Francisco Lowrider Parade Grand Marshal. We recorded this podcast over Zoom in September 2025. Photo of David by Anthony Gonzales

In Part 2, we pick up where we left off in Part 1. Although it made all kinds of sense for Shrey to move halfway around the world to go to art school, he says it was "an uphill battle" convincing his parents of the plan. Still, his mom was and is a champion of her son and his art. It was 2018 and Shrey was 20. We talk about his experience of arriving in San Francisco, a city that was "such a beacon of hope" for him. He dedicated himself to his studies at CCA. He also paid serious attention to the news, and even attempted political art. When that didn't pan out financially, a professor at CCA strongly encouraged Shrey to stay with painting, that it was his lane. This was just before the pandemic. When he got his first stimulus check, Shrey bought an easel and began going out and painting en plein air. He did this so much and promoted his art so well that, by the time he graduated, he had started getting commissions. He was able to become a full-time artist—a dream of his. Shrey is such an artist, through and through, that he even has an art job. Like, a job-job. Four days a week, Shrey works for ArtSpan—a local arts nonprofit possibly best-known for Open Studios. Shrey shares the history of ArtSpan and OpenStudios. What began in 1975 in South of Market as a way for artists shunned by galleries to show their art and sell it today sees around 600 artists opening their studio doors all over The City. Shrey manages the Arts and Neighborhoods program for ArtSpan. That group helps organize exhibitions during Open Studios at non-studio locations. Mission Bowling Club is one such location. In fact, Shrey got his first art show after graduation through help from ArtSpan. It's a beautiful full-circle story. That first show led to other shows. And Shrey credits his entrepreneurial brain for recognizing an opportunity in all of this—if a cafe has suitable walls, you can talk with the owner about hanging art by local artists, promote an opening, and make things happen. And so that's what he did. Partly because putting on one art show, not to mention doing multiple shows at the same, is what the kids refer to as a lot, Shrey focussed his efforts at one location. Ballast Coffee on West Portal became the home of Ingleside Gallery. The first art show at his gallery brought in more than $10,000 in sales. I have to insert some editorial here, so thanks for indulging me. Shrey and I recorded this podcast before our Every Kinda People show. I won't pretend that my own art curation is anywhere close to the level that he (and my friend Anita of KnownSF and countless others around SF, The Bay, and the world) operates on. But Shrey does speak to the nature of both the volume and the intensity of the work that goes into putting on an art show. In my own way, I relate. Back to my and Shrey's conversation, I ask him to talk about how our lives intersected. It was earlier this year after I recorded with Ellen Lo of Ask Me SF. I needed to drop off a Storied: SF hoodie for Ellen, so she asked me to meet her one Saturday morning on Ocean Avenue. She and some friends and community members would be out there painting a mural over a dilapidated street wall in front of a PG&E substation. Sign me up! After politely declining to add my own (attempted) artistic touch to their creation that day, Ellen introduced me to a friend of hers. Right away, I got a sense of that exuberance Shrey embodies, a trait I am now very familiar with. We end the episode with thoughts about the Every Kinda People show, up at Mini Bar through October 19. Follow Shrey on Instagram @shreypurohit and @inglesidegallery.