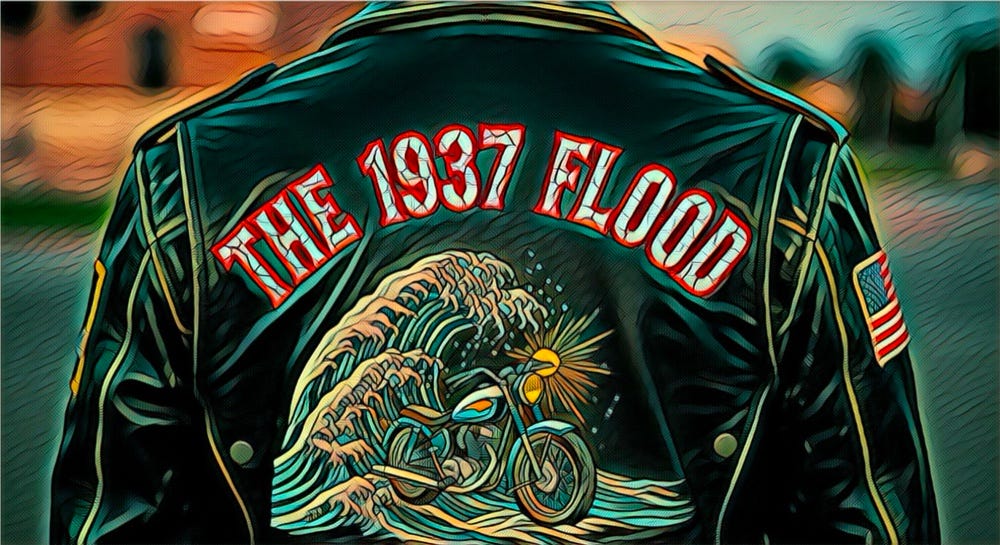

Discover The 1937 Flood Watch Podcast

The 1937 Flood Watch Podcast

The 1937 Flood Watch Podcast

Author: Charles Bowen

Subscribed: 0Played: 1Subscribe

Share

© Charles Bowen

Description

Each week The 1937 Flood, West Virginia's most eclectic string band, offers a free tune from a recent rehearsal, show or jam session. Music styles range from blues and jazz to folk, hokum, ballad and old-time. All the podcasts, dating back to 2008, are archived on our website; you and use the archive for free at:

http://1937flood.com/pages/bb-podcastarchives.html

1937flood.substack.com

http://1937flood.com/pages/bb-podcastarchives.html

1937flood.substack.com

243 Episodes

Reverse

Wrapping up a recent Christmas party at which we had a houseful of friends and neighbors (including our buddy Jim Rumbaugh sitting in as a guest artist), The Flood unwrapped its new anthem to winter. It is this mashup of “Moscow Nights” and “Greensleeves.” Today we make this performance our gift to you. Merry Christmas from the Floodisphere!The SongsLet’s talk about the bits and pieces that make up this jolly seasonal offering.“Moscow Nights”As reported earlier, “Moscow Nights” was composed in 1955 by Russian musician Vasily Solovyov-Sedoy. It was originally entitled “Leningrad Nights,” but, it being the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Ministry of Culture directed it be renamed to celebrate Moscow and directed corresponding changes to poet Mikhail Matusovsky’s lyrics.For the first half dozen years of its life, the song was known primarily in the Soviet Union, The melody didn’t hit the big time in the U.S. until November 1961 when trumpeter Kenny Ball and his Jazzmen recorded it under the title "Midnight in Moscow.” For the recording, Ball was inspired by an arrangement he heard by a Dutch jazz group called “The New Orleans Syncopators” who recorded the melody earlier that year.But there is a lot more to this story. Like when The Chad Mitchell Trio’s controversially battled with the U.S. State Department over performing the song in foreign lands. And like the time that Flood manager Pamela Bowen got kudos for performing the song in its original Russian during her folksinging days as a student at Marshall University. Click here to read these and other “Moscow Night” yarns.“Greensleeves”The song’s musical team mate in this track — “Greensleeves” — probably is the oldest melody we know. It has been associated with Christmas ever since a century and half ago when the tune was set to the verse “What Child Is This?” But the song originally wasn’t religious in nature at all. On the contrary, as reported here, its earlier lyrics told the story of a painful romantic conundrum (with some, uh, subtly salacious references). Popular legend even has sometimes attributed the song’s composition to England’s King Henry VIII, who was said to have written it for the ill-fated Anne Boleyn. That association, though, is wrong, says author Lisa Colton in her book Angel Song: Medieval English Music in History. Colton finds “Greensleeves” originated a generation later, during the reign of Henry’s daughter, Queen Elizabeth I. First published in 1580, the tune was used for a wide variety of 16th and 17th century broadside ballads.And there’s much more to this back story as well. Click here to read it.Reviewing 2025This is our last podcast of the year. We look forward to roaring into 2026 with you all. Meanwhile, if you’d like to get a jump on your auld-lang-syning, you can tune into a randomized playlist of this year’s 52 podcasts via the band’s free Radio Floodango music streaming service. Click here to give it a spin. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

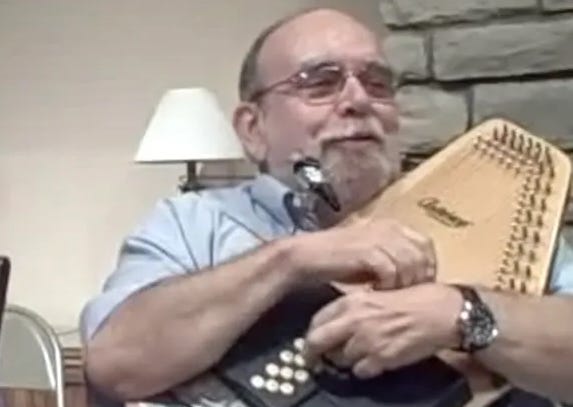

It was 16 years ago tonight at the Christmas Eve-eve-eve party in the Bowen House that the late Dave Peyton gifted us with a classic rendition of his all-time favorite John Prine tune. And fortunately, Pamela Bowen had her camera running to preserve the video above.“Come Back to Us, Barbara Lewis Hare Krishna Beauregard” was introduced on Prine’s 1975 Common Sense album, but the song didn’t really resonate with Br’er Dave until he heard it again about a dozen years later as the opening track on the John Prine Live album.By that time, The Flood had gone in recess, as reported here earlier, but the song was still very much on David’s mind when the band reconvened in the mid-1990s, and “Barbara Lewis” then kept coming back to us in the years to come.About the SongThe late John Prine said in the liner notes for that 1988 “live” album that he wrote “Barbara Lewis” in the summer of 1973 while he was touring Colorado ski towns with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. The lyrics were inspired, he said, by the “leftover hippies” he encountered in the Rocky Mountains, people who had drifted through various counterculture movements and religions without ever making it all the way to California.It was, he said, as if they got to the Rockies and said, “God, I can’t get over that,” and just settled in.Besides that, John added, “I had different friends of mine who went through the ‘60s, from being totally straight or greasers, then turned into hippies, and then into a religious thing. So I created this character who had done all those different things.”About the title, Prine said he got the name Barbara Lewis from the R&B singer (”Hello Stranger,” 1963; “Baby, I’m Yours,”1965). And the rest of the name of the character? “It just falls off the tongue really nicely,” John said, noting he often tried to match a syllable for each note. “I call it the Chuck Berry School of Songwriting. He’s got it so dead-on that you can just read his lyric, and that would be a melody.”More John and More DaveIf this single song doesn’t completely satisfy your Flood needs right now, you can have many more helpings at the band website’s free Radio Floodango music streaming service.For instance, if you’d like more Floodifying of John Prine songs, check out our John Prine Memorial playlist. Click below for the details:Meanwhile, if you’d like to listen again to some of the many beloved tunes featuring our old buddy Dave Peyton, check out the David Channel.Click here to give it a spin! This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Christmas is usually a pretty raucous time in our band room, with old friends coming back around and new friends ... well, new folks just starting to figure us out. Yes, indeed, we do tend to take those tidings of comfort and joy at their word.And our holiday celebration is especially memorable if we can get that jolly ol’ Jim Rumbaugh back into the room, as we did at a recent festive gathering at the Bowen House. To make the season bright, we always try to get Jim doing his bluesy Christmas contribution, a song he calls, “Got My Yule Log Burnin’.”Jim’s path to writing the tune began while he was working at his wife Donna’s greenhouse, which sold Christmas trees every year. As part of the business, Donna made wreaths, which required pieces of greenery. Jim was tasked with taking the reject trees and cutting off their branches so she could use them for the wreaths. This process left him with substantial pieces of pine log, typically five to seven feet long, which he then had to cut into foot-long pieces to be bundled and sold as Yule Logs.While cutting these logs, Jim began pondering the purpose of the items he was creating, wondering if anyone actually burns a Yule Log.“I thought, ‘I wonder if there’s a Yule log-burning song?’ and I started singing, ‘Got my Yule Log burning,’ which sounded a whole lot ‘Got my mojo working!’”Well, after that, all that was needed was a bit of Christmas cheer and space for a couple of well-tempered harmonica breaks. Demonstrating the results, Jim got everyone in the room singing along, as you’ll hear here!To Keep the Holidays Bright…So, Merry Christmas from your friends in The Flood.And for a little more fa-la-la-la-Flood in your festivities in this week’s countdown to Christmas, remember the Radio Floodango free music streaming service has this yuletide playlist.Click here to give La Flood Navidad a spin!More from the Righteous Mister RumbaughMeanwhile, if today’s podcast has you wanting more helpings of Jim Rumbaugh’s bluesy offerings, you’re in luck! Jim is the star of a popular episode in the “Pajama Jams” video series that The Flood released back in 2021. Click below to check it out! This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

The story goes that folkie John Denver was just 22 years old when he played at Arizona’s Lumber Mill Club in Scottsdale and met a girl named Bobbie Wargo.The two had much in common. Both grew up in military families. Both were musicians and aspiring songwriters. Both were looking for love.And love was what they found as they played together at her parents’ piano. It was for her that John wrote one of his first songs. And “For Bobbie” was to be the first original tune that Denver ever recorded. I’ll walk in the rain by your side, I’ll cling to the warmth of your hand…Bobbie Wargo may have contributed to the song’s lyrics; there is evidence that she also might have been the inspiration for his next song, “Leaving on a Jet Plane.”(All of this was half a decade before John Denver met the iconic “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” recorded it and, as reported here earlier, became forever an honorary Mountaineer.)“For Bobbie” was, as Denver later told writer Deborah Evans Price in American Songwriter magazine, “an early attempt to order my romantic thoughts.”The Song’s Recording HistoryThe song was first recorded by the Mitchell Trio under the truncated title of “For Bobbi” in 1965, the same year in which Denver joined the group, replacing founder Chad Mitchell who had moved on to a solo career.The following year the song took a whole new turn when Mary Travers (of Peter, Paul & Mary) rechristened it “For Baby” and recorded it to honor her young daughter Erika. Travers changed the meaning to reflect a mother’s love for her newborn, and this version gained significant popularity. The song appears on the 1975 Peter, Paul & Mommy, Too album as part of a medley entitled “Poem for Erika/For Baby” That wasn’t PP&M’s first outing with it; nine years earlier, in 1966, “For Baby (For Bobbie)” appeared on the group’s sixth studio release called simply Album.Meanwhile, Denver himself re-recorded the song — this time also listing it as “For Baby (For Bobbie)” — on his popular 1972 Rocky Mountain High, his first Top-10 album.In the seven years between Denver’s first and second release of the song, a half dozen other artists covered “For Baby (For Bobbie)” including Bobby Darin (1966), Dion and the Belmonts (1967) and Anne Murray (1968).Our Take on the TuneOne of the first tunes that Charlie Bowen and his cousin Kathy Castner did when they started singing together more than 30 years ago was Denver’s lullaby-like love song. So it’s only natural that “For Baby (For Bobbie)” is in the mix whenever Kathy gets to make one of her rare trips from Cincinnati to Huntington to sit in with the band. Here’s a take on the tune from last weekend.Since Flood harmonicat Sam St. Clair couldn’t make it that evening, we corralled the player whom Sam lovingly calls his “overstudy,” the incomparable Jim Rumbaugh, to sit it and bring some memorable solos.And Now From the Wayback Machine…Oh, and want a little trip down mem’ry lane? Here’s a video of a For Baby Moment that Pamela Bowen caught almost a decade and half ago:From the summer of 2011 in the Bowen House, this performance is complete with sweet solos by Dave Peyton and Jacob Scarr. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

At a good rehearsal — and, heck, that’s just about every rehearsal nowadays — none of us really wants it to end. Oh, sure, we get tired — two hours of hard picking take a toll — but as Gladys Knight used to say, none of us wants to be the first to say goodbye.In fact, as you hear at the conclusion of this week’s podcast, which features the final tune of a recent rehearsal, we often even keep extending the ending, jockeying to be the one to play the last note.The moment is always really fun if that last tune of the night is an especially goofy one, and you can’t get much goofier than “Yas Yas Duck.”About the SongThis late 1920s hokum song came into The Flood’s life more than 40 years ago. In fact, it had its public debut at what turned out to the last of those semiannual music parties that birthed the band, as seen in this excerpt from the “Bowen Bash Legacy Films” series:In those days — the above audio is from September 1981 — chasing down the history of these quirky little tunes was challenging. The World Wide Wide was still more than a decade away, so to suss out songs’ back stories, we had to rely on often sketchy liner notes on rare albums and on even rarer books covering esoteric genres.We learned our version of the song from a 1973 Yazoo Records compilation called Tampa Red, Bottleneck Guitar (1928-1937), the same record we studied so we could cop other Tampa tunes like “What’s That Taste Last Gravy?” “Black Eyed Blues” and “No Matter How She Done It.”Mastered by Nick Peris, the LP featured liner notes by Seattle bluesman John Miller who gave us no hint of the song’s colorful evolution. For years, we just assumed that it was another of Red’s collaboration with Georgia Tom Dorsey.Only recently were we able to use web resources to determine that the song traces back to what Wikipedia characterizes as “a ‘whorehouse tune,’ a popular St. Louis party song,” first recorded in January 1929 by a great St. Louis piano pounder named James “Stump” Johnson. It would be four months later before Tampa Red and Georgia Tom recorded their version in Chicago.For more about “Yas Yas Duck” (and all its various alternate names), check out our earlier Flood Watch article by clicking here.Latest Floodification of The DuckAs you’ll hear on this track, this hokum classic, whether it comes at the beginning of an evening of music or at the end, is always good for a few laughs.As noted above, it was 1981 when The Flood first publicly played the tune. But the song was still very much in Flood Consciousness 20 years later when the band made its first studio album. Click the button below to hear the album track from 2001: This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

This song, while beautiful at any time of the year, is especially resonant at the dawn of a new holiday season. So this morning, as our Thanksgiving gift, here’s The Flood’s latest performance of the late Michael Peter Smith’s evocative “Spoon River.”Thanksgiving, as a season celebrating the bonds of friends and families, is a particularly good time to appreciate a song that reminds us in the very first verse how “all our lives were entwined to begin with.”As we noted an earlier in Flood Watch article, Smith once famously commented, “I like songs that delight in giving you a picture,” and “Spoon River” does that in spades, from images of riverboat gamblers and Union soldiers to the calico dresses in the attic along with Grandfather’s derringer case.Thanksgiving gatherings often involve opening drawers, unlocking old doors and retelling stories to reconnect with ancestors through the objects they pass down.And more. Our favorite lines, at the end of the second verse — There are words whispered down in the parlor, a shadowy face. The morning is heavy with one more beginning ….— evoke the way that memory itself seems to drift through a house during the holidays, the past present with the living. May this song bring you joy and sweet memories as you come and ride through the morning. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Here’s another tune that Danny Cox has brought to us from his decades of lovingly listening to Chet Atkins and Jerry Reed’s famous recordings.One of Jerry’s composition, “Baby’s Coming Home” is a standout tune that was introduced on 1974’s landmark Chet Atkins Picks on Jerry Reed album.As reported here earlier, Atkins and Reed were not only esteemed guitarists but also good friends who shared a profound musical chemistry. A major figure at RCA, Atkins was instrumental in bringing Reed to the label.The album testified to Atkins’ continued endorsement of the younger man’s talent, showcasing interpretation of 10 of Reed’s unique and often humorous compositions. Chet and Jerry were known for their distinct fingerpicking styles, drawing inspiration from pioneers like Merle Travis and incorporating their own original, complex techniques. This is what attracted Danny Cox to their work when he was still just a teenager learning to pick.About the SongJerry Reed wrote “Baby’s Coming Home” around the time Chet was coming up with the plans for his 1974 tribute album. Atkins’ rendering of the song is the first track of the disc’s B side. Incidentally Jerry himself performed on only two of the album’s tracks (”Squirrely” and “Mister Lucky,” and sadly not on “Baby’s Coming Home”). However, a few years later, he and Chet did pick the tune together on TV. That wonderful, light-hearted segment was preserved on this YouTube video:A Muppet MomentBy the way, four years later, “Baby’s Coming Home” made a curious comeback. This time with a tuba-and-banjo-heavy Dixieland-flavored arrangement, the song was the soundtrack for a sketch called “Lunchtime” during Episode 316 of The Muppet Show. Check this out:More Atkins-Reed Collaboration Chet Atkins Picks on Jerry Reed reminded many fans of Chet’s Grammy-winning 1970 Me and Jerry release, an all-acoustic, instrumental album that featured the two buddies teamed up on a range of songs, from country and pop covers to original instrumental workouts.Several decades later, this collaboration was followed by another celebrated joint effort, the 1993 Grammy-winning Sneakin’ Around album. More from Danny?If all this has you in the mood to put a little more Danny Cox into your Flood Friday, drop by the free Radio Floodango music streaming service and give the Danny Channel a spin.Click here to check it out! This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Educated ears in the summer of 1957 were still trying to decide if this new rock ’n’ roll thing was really music’s future or was just a passing fancy.Two summers had passed by then since the new sound burst upon the American scene. The ear-opening “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley & His Comets was quickly followed by Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” and Little Richard’s “”Tutti Frutti.”The following summer the rock kept rolling, when The King arrived. This new kid, Elvis Presley, topped the charts for weeks on end with “Heartbreak Hotel,” with “Hound Dog,” with “Don’t Be Cruel.”But by 1957, the cigar-chomping bigwigs in the record company boardrooms still weren’t sure. Not sure sure, you understand.The Summer DoldrumsAfter all, traditional pop crooners seemed to be staging a comeback. Perry Como (of all people!) hit No. 1 with “Round and Round.” Pat Boone scored with the languid “Love Letters in the Sand.” Debby Reynolds had a hit with “Tammy.” Holy schlock, Batman, even Elvis seemed to be getting goo-goo eyed all of a sudden with “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear.”So, the question in ‘57: where were summertime’s rebels? That year the cool kids had already packed up their beach towel and gone on back to school by the time rock’s Next Big Wave hit:— Sept. 9, 1957, Buddy Holly and The Cricket, “That’ll Be the Day.”— Oct. 11, 1957, Everly Brothers, “Wake Up Little Susie.”— Oct. 21, 1957, Elvis, “Jailhouse Rock.”— Dec. 21, 1957, Danny and the Juniors, “At the Hop.”But even before that fall, diehards could dig a little deeper in the radio playlist for up-and-coming rockers. Jerry Lee Lewis was howling away with “A Whole Lot of Shakin’.” Fats Domino was still down there somewhere with “I’m Walkin’.” Jackie Wilson was right on deck with “Reet Petite.”About This Week’s SongAnd languishing even further down on the summer music charts — oh, somewhere around No. 24 or so — was the subject of this week’s podcast. It’s The Flood’s favorite souvenir from the Summer of ‘57: The Coasters’ wonderful “(When She Wants Good Lovin’) My Baby Comes to Me.”As reported here earlier, this winking and nodding Jerry Leiber-Mike Stoller composition was a minor hit for The Coasters. It did resurrect nine years later when a little known group called The Chicago Loop took it for a spin and got to No. 37 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.But in the Floodisphere, we much prefer a different pressing of the song released one year earlier. Favorite folksinger Tom Rush’s 1965 self-titled debut Elektra album included a version of the tune accompanied by bassist Bill Lee along with John Sebastian (of The Lovin’ Spoonful) and Fritz Richmond (of The Jim Kweskin Jug Band.)This track, captured at last week’s rehearsal, features the arrangement we’re working up to include on the new album when we start recording in the weeks ahead. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Fourteen years ago this week, The Flood had a wonderful evening with a local legend, a gentle soul named Mark Keen. Visiting from his Pittsburgh home, Mark sat in on harmonica for a rollicking evening of blues. Growing up in Huntington, Mark and a long-time Flood buddy, guitarist Randy Brown, went all through school together here back in the ‘70s. Mark didn’t get back to Huntington very often, but when he did, Randy brought him around to jam with The Flood on the evening of Nov. 9, 2011. The video above — shot by Flood manager Pamela Bowen — is a homage to that night.The Keen FamilyIt was one of Mark’s rare visits back to his hometown since his father’s death. Leonard Keen died in 2009 at age 94 after nearly 50 years of running a fixture on Huntington’s 9th Street, Keen Jewelers.Born in Cincinnati in 1914, Leonard served in the U.S. Navy and during the Great Depression worked for the federal Works Progress Administration.In a story in his “Lost Huntington” column in The Herald-Dispathc, local historian James E. Casto quoted Keen as saying, “My wife was a native of Huntington. So during a visit to her parents, we decided that Huntington would be a good place to open a store.”Keen and his wife Betty Ann moved from Louisville to Huntington and in April 1958, Mayor Harold Frankel helped cut the ribbon at their new store, which was located at 322 9th St. Exactly 20 years later, on April 16, 1978, after urban renewal forced the jewelry store to relocate, Frankel again did the honors, helping Keen cut the ribbon at a new location, just down the street at 419 9th St.Leonard and Betty’s son Mark was born in 1952 and grew up in Huntington, a talented drummer and harmonica player who performed with bands here and later in the Pittsburgh area.Mark’s PassingAfter The Flood’s delightful jam that November evening at the Bowen House, we never got to see Mark again. A half dozen years later, he passed away at 65 at home in Oakmont, Pa., of natural causes.Following a celebration of Mark, he was interred at Huntington’s Spring Hill Cemetery. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

From a thousand miles away, Matt Whyte has been a Flood fan for at least a decade and a half, but until recently he was never in the same room with the band.Instead, Matt always had to limit his Floodifying to singing along with the albums he received from his mom, JoAnn McCoy.But he was attentive to his studies. We know that because last week when he and JoAnn finally traveled from their Bradenton, Fla., homes to reach the Bowen House for his first in-person Flood encounter, Matt was so well-versed that he had specific requests for tunes he’d like to hear.Top of the ListHis favorite? Matt has a particular affinity for “Didn’t He Ramble?” a tune that he learned from the band’s 2011 Wade in the Water album. That rollicking century-old song relates the deeds and misadventures of a rambling ne’er-do-well named Buster: Mama raised three fine sons, Buster, Bill and me, Buster was the black sheep of our little family….The opening verse’s second couplet, though, is the one that most resonates with our young Matt: Mama tried to quit him of his rough and rowdy ways. She finally had to have the judge to give him 90 days!That struck a chord because nowadays it is Matt himself who often hands out such sentences. You see, back in Bradenton, JoAnn’s son is Judge Matthew Whyte for Florida’s 12th Judicial Circuit Court for DeSoto, Manatee and Sarasota counties.Matt’s Vocal ContributionMatt even has a favorite part of his favorite Flood tune. The second verse of “Didn’t He Ramble?” begins: He rambled into a swell hotel, his appetite was stout, But when he ‘fused to pay the bill, the landlord throwed him out.On the original Wade in the Water album cut, the late Dave Peyton underscored that moment with an emphatic “Get out!”“I laugh every time I come to that part,” Matt told us at last week’s rehearsal. So it was just natural that when we played his tune for him and we came to that spot, we let His Honor do the honors. You can hear the debut Matt Whyte Solo at 01:39 in this week’s podcast.A Family Tradition of FloodishnessAs noted, Matt Whyte’s Flood interests are a family tradition. Beginning in 2006, Matt’s mom, JoAnn, and her husband, the late Bob McCoy, were often in the room for the weekly Flood gatherings, sharing jokes and stories, smiling at our progress on their own favorite tunes.The pair was on hand for some important Flood events, from the debut of Jacob Scarr, the 14-year-old guitar savant whom we called “Youngblood,” to the beginning of the weekly Flood podcasts in 2008. One of the first podcast listeners was Bob when he and JoAnn returned to Florida that December. Sometimes he and JoAnn even challenged traffic regulations on their drives north, just to reach the room before the music started.No wonder JoAnn was eager to share her Flood love with her son Matt.About the SongWhen the great Charlie Poole and his North Carolina Ramblers recorded “Didn’t He Ramble?” in 1929, the song already was more than a quarter of a century old, with roots in the New Orleans of Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton.But, as we reported in Flood Watch a while back, the seeds of the song are planted even deeper than that. For instance, the song’s key lines (Didn’t he ramble? Didn’t he ramble? / Oh, he rambled till the butcher cut him down!) crop in a Texas work song that was published in 1888.For more on the song and its wild and rambling history, click here to read that old Flood Watch article.Meanwhile, 800 Songs Along Incidentally, this is the 800th episode of The Flood’s weekly podcast since it began 17 years ago next month.That means that the website now has more than 50 hours of free Flood music online, contributed at a rate of four or five minutes a week. Click the link below for details on those developments:Meanwhile, a few years ago, that deep, broad database of all those Flood tunes inspired us to roll out our most ambitious project to date. Radio Floodango, the free music streaming service, lets you listen to a continuous, randomly generated playlist of Flood tunes whenever/wherever you’d like. For more about that, check out this earlier article. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

It’s not easy to make the top dozen in CMT’s “100 Greatest Love Songs,” but that is precisely the placement that the music network awarded to Keith Whitley’s recording of “When You Say Nothing At All.”The song has a beloved place in our hearts. We remember the Christmas Eve in 1988 when that lovely number hit No. 1 in Billboard’s Hot Country Singles.And for many of us, that is the sweet tune that first came to mind just five months later in a much sadder moment: when we heard the shocking news that 34-year-old Whitley had died at his Goodlettsville, TN, home.One of UsThe news hit especially hard in our area. Keith Whitley was a local hero. Born in Ashland, he grew up in the nearby Sandy Hook, Ky.It seemed like every one of that town’s thousand residents knew Keith, but conversation was almost non-existent on the day of his passing. Words lost out to stunned silence.Today his memory is permanently etched into the landscape. A street is named “Keith Whitley Boulevard.” A memorial statue stands near the Elliot County Veterans Memorial and Cemetery. Peaceful, it is hallowed ground.Our Channelling KeithSome songs are like old friends. This old Paul Overstreet-Don Schlitz tune is certainly like that. We hadn’t played it in six months or more, and then one sultry night last August, it strolled back into the band room like it had never left. Danny Cox kicked off those familiar first chords. Randy Hamilton stepped up with the opening lyrics, and this was the result.For more about the history of how this song came into being, see this earlier Flood Watch article. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Often over the years, this tune has conjured up a very specific gig memory for Floodsters.It dates back to a weekend when the band was invited to the top of West Virginia’s Snowshoe Mountain to be part of a rather swank do (“a wine and cheese affair,” as the late Joe Dobbs liked to call such jobs).We were on a stage under a huge event tent on the grounds of Snowshoe ski resort in Pocahontas County. The summer evening breeze was sweet. The glasses were tinkling. Then, toward the end of the night, a jolly gypsy troupe of motorcyclists rolled and crashed the party.We didn’t know what would happen next. For a moment there, it looked to some of us like that edgy turning point in a Tarantino picture.But just as suddenly, the guys in leather and the guys in suits started mingling together, laughing, drinking, swapping stories. Deep in The Flood’s memory banks to this day are images of that eclectic crowd of bankers and bikers singing along as one on this song. “Ohhhhh, MAma! Ain’t you gonna miss you best friend nowww!”About the SongAs reported in an earlier Flood Watch article, Bob Dylan’s “Down in the Flood” was one of many songs that would fill the world’s first great bootleg albums, like the unforgettable Great White Wonder, which made the rounds from 1969 onward. (Nearly all those tracks later were officially released by Columbia Records as The Basement Tapes.)It turns out that “Down In The Flood” (also known as “Crash on the Levee”) evolved during a specific 1967 jam session at the Woodstock, NY, in the house that the guys dubbed “Big Pink.”As The Band’s Robbie Robertson remembers it, at that session Bob and the boys started fiddling with an old John Lee Hooker song called “Tupelo Blues,” about the historically devastating 1927 Mississippi River flood. That tune apparently triggered Dylan’s memories of another song, one from his repertoire in the early years, called “James Alley Blues,” based on a 1927 Richard “Rabbit” Brown recording. Significantly, that song uses the phrase “sugar for sugar, salt for salt,” a line that would find its way into Bob’s own lyric.For more on the song’s history, click here to read that earlier article.Our Latest Take on the TuneBob Dylan once famously spoke in another 1960s song about “a thousand telephones that don’t ring.” But that’s hardly a problem for us in our new millennium. On the contrary, we’re all walking around with phones in our pockets that are apt to sound off at the most inopportune moments. Like in the middle of this track from last week’s rehearsal when Sam St. Clair’s phone chimes in. But our Sam’s an especially cool lad, so you’d that expect even his phone’s ringtone would contribute something special. And it does. Wait for it: at 02:43, a nifty xylophone audition at mid-song!More Bobby? Step Right Up!The Flood does a lot of Bob Dylan tunes, of course. We even have a special playlist of them that we put together for a Dylan birthday observance a few years ago. Click below to read all about it. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

When Thomas A. Dorsey (a.k.a. “Georgia Tom”) walked out of a New York City recording studio in the winter of 1932, he ended a highly successful music partnership with Tampa Red (a.k.a. Hudson Whittaker).Over four years, Red and Tom garnered a happy following for their infectious, highly danceable brand of blues tunes.In 1928, the two young men had teamed up and recorded for the Paramount label the hit “Tight Like That.” The success of that number — based on Blind Blake’s “Too Tight” and on Papa Charlie Jackson’s “Shake That Thing” — inspired imitators and launched the blues genre known as “hokum,” as reported here earlier, Whittaker and Dorsey recorded more than 60 sides together, often under the name “The Famous Hokum Boy.” Some of these rollicking tunes have been covered by The Flood over the years, songs like “Somebody’s Been Using That Thing,” “Yas Yas Duck” and “You Can’t Get That Stuff No More.”And add to that list the last tune that Tom and Red ever recorded together. The composition they called “No Matter How She Done” was waxed on Feb. 3, 1932, and released that spring on Brunswick’s Vocalion label.Nothing in Red’s sassy lyrics hinted at an end to this lucrative collaboration: The copper brought her in, she didn’t need no bail She shook it for the judge, they put the cop in jail! As we noted in an earlier Flood Watch report, when Dorsey left the blues field in 1932 to take up a career as gospel songwriter and choir director, Whittaker continued as a solo blues artist well into the 1940s.Floodifying ItFlash forward seven decades. When The Flood started doing this song in the early 2000s, we committed what some folk purists consider a sacrilege: We altered both its title and its hook, removing one entire syllable. Instead of Tampa Red’s original “No matter how she done it” lyric, The Flood opted to sing “Any way she done it.”We’re still doing it that way, in fact, as you hear in this track from a recent rehearsal. And, no, we have no excuse, not really, except an aesthetic one. We felt the revision simply allowed the line to flow more easily off the tongue. (Call your neighborhood linguist and ask about the joys of removing “alveolar taps.”)One thing for sure: now, as then, the new phrasing does facilitate group singing, as you can hear on the band’s lively original rendering 20 years ago on our Plays Up a Storm album. Click the button below to hear it:That track, recorded on the evening of Nov. 16, 2002, featured Sam St. Clair, Joe Dobbs, Doug Chaffin, Chuck Romine, David Peyton and Charlie Bowen.The Bob Wills ConnectionWhile the tune (any way we sing it) has always had a happy hokum vibe, “No Matter How She Done” took a curious turn four years after Tampa Red and Georgia Tom’s inaugural recording.In September 1936 in Chicago, the song got a cool country treatment by no less a luminary than Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys.This was just three years after Wills organized the band in Waco, Texas, and set about defining the style of music that’s come to be known as “Texas swing.”Released as a single in May 1937, “No Matter How She Done It (She’s Just a Dirty Dame)” was recorded in Wills and the Playboys’ second major recording sessions for the American Record Corporation.The session is particularly important for Wills collectors, because it features the lineup that would define the Texas Playboys sound for years to come, including vocalist Tommy Duncan, pianist Al Stricklin, steel guitarist Leon McAuliffe and drummer Smoky Dacus.More Hokum, You Say?Meanwhile, if more hokum music is what you need to make your Flood Friday complete, remember that we’ve got a whole channel waiting for you on the free Radio Floodango music steaming service.Just drop in and click the “Hokum” button or, better yet, just use this link to jump to it directly. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Danny Cox has an abiding love for the works of guitar heroes Jerry Reed and Chet Atkins, and the song “Drive In” — which Dan brings to this week’s podcast from a recent rehearsal — beautifully displays those intersecting energies.As reported here earlier, Reed often wrote wonderfully tasty riffs and licks only to forget them the next day when he moved on to some new project. Atkins, a detail-driven professional and a successful producer, completed and recorded many of Jerry’s pieces, practicing and polishing them to perfection.It was one of these fertile periods of Jerry’s noodling and Chet’s cultivating that produced “Drive In.” Chet was the first to record the piece, the opening track of his acclaimed 1968 Solo Flights album.Later John McClellan’s book Chet Atkins in Three Dimensions: 50 Years of Legendary Guitar included a transcription of the tune, further cementing its place in Chet’s legacy repertoire. It’s no wonder that these days that the song is a popular vehicle for aspiring pickers on YouTube.More from Danny?If all this has you in the mood to put a little more Danny Cox into your Flood Friday, drop by the free Radio Floodango music streaming service and give the Danny Channel a spin.Click here to check it out! This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

The sing-along — “if you know it, sing it!” as we say around here — is fundamental to folk music. As folk music’s guiding spirit, the late Pete Seeger, once said, “I rather put songs on people’s lips than in their ears.” Pete believed songs offered powerful magic to bring unity. “Get people to sing together,” he said, “and they’ll act together too.”“Once upon a time,” he said, “wasn’t singing a part of everyday life as much as talking, physical exercise and religion? Our distant ancestors, wherever they were in this world, sang while pounding grain, paddling canoes or walking long journeys. Can we begin to make our lives once more all of a piece?”We love how Seeger broke that idea down.“Finding the right songs and singing them over and over is a way to start. And when one person taps out a beat, while another leads into the melody, or when three people discover a harmony they never knew existed, or a crowd joins in on a chorus as though to raise the ceiling a few feet higher, then they also know there is hope for the world.” “I’ve often thought,” Pete said, “standing onstage with 1,000 people in front of me, that somebody over on my right had a great-great grandfather who was trying to kill the great-great grandfather of somebody off to my left. And here we are all singing together... Gives you hope.”About This SongFor us nowadays, there’s no better sing-along than this tune, which the newest Floodster Jack Nuckols brought us about a year ago, a song that stars the beautiful Ohio, which rolls and flows beside our towns and through our hearts.The song “Shawneetown” is a wonderful reflection on the early history of boating up and down the Ohio River. While it sounds like an old tune, it is largely a 1970s composition by folk artist Dillon Bustin.As we reported here earlier, Bustin based the first verse and chorus on historical fragments published in 1828 and quoted in Leland D. Baldwin’s 1941 book, The Keelboat Age on Western Waters, including: Some rows up, but we rows down, All the way to Shawneetown, Pull away — pull away!Bustin, who combined these fragments, composed the tune and several additional verses for the song we have now. Shawneetown is in southern Illinois where the Ohio meets the Wabash River. It was the first Anglo settlement on the Ohio, serving as a major trade center and a government administrative center for the Northwest Territory in the early 19th century. Keelboats were the most efficient commercial vessels of the time.The song’s first studio recording was likely the 1978 rendering by American folk duo Malcolm Dalglish and Grey Larsen. It appeared on their First of Autumn album.For more history of this good old tune, see this earlier Flood Watch article.And Even More Song HistoriesAnd speaking of song histories, we have back stories on more than 200 of the tunes we play.Check out Flood Watch’s free Song Stories section and click on a title to see what we have on file about it. You can browse them alphabetically by song titles or chronologically by the years in which they were written. Click here to give it a look. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

In his quarter century with The Flood, the late Doug Chaffin brought dozens of great tunes to the band, and the loveliest of the bunch was one of the last.The truth is we always listened to everything Doug told us, because his musical instincts were usually right on the money. For instance, whenever we were playing a show and Doug leaned over and whispered, “Hey, maybe we oughta do this song next,” Charlie Bowen revised the set list on the fly, because Doug had a sixth sense about what people would like to hear. That’s why a half dozen years ago, when Doug told us we ought to learn “Amelia’s Waltz,” we perked up. The song ended up being one of the sweetest tracks on our 2019 Speechless album, as you can hear in the video above.The piece you hear sounds like an old tune, but it actually was written in 1981 by Bob McQuillen, the late New Hampshire composer, who penned it in honor of the then-three-and-a-half year-old daughter of a friend and fellow musician, a woman named Deana Stiles.“Amelia’s Waltz” is one of those sweeping melody that sounds like it ought to be the soundtrack of a big, lush movie. And it turns out that the plot of such a movie could easily be based on the tune’s very namesake.So, Who is Amelia?Considered the dean of contra band music in America, the late Bob McQuillen — “Mac” to his friends — wrote some 1,300 tunes in his 60 years of playing. Most of his compositions he named after people or events in his New England life, and the song named “Amelia’sWaltz” is one of his best.Besides having a gorgeous song named for her, Amelia Stiles’ other claim to fame is that she was born in a New England curiosity, a structure called “The Lindbergh Crate,” and…. well, heck, let’s let Mac himself tell that tale. A few years before his death in 2014 at age 90, McQuillen was interviewed by a Danish fiddle website about the back story of “Amelia’s Waltz” and here’s what he told them.“This is sort of complicated,” he began. “After Charles Lindbergh flew across the ocean in the Spirit of St. Louis, the thing was to get the plane back. They took the wings off and put them in one crate and the fuselage in another, then sent the whole thing back to this country aboard ship. “I don’t know where the wings box went, but the fuselage crate eventually wound up on the banks of the Black Water River in Contoocook, a little town in New Hampshire.” Later, someone added a slanted roof to the crate and turned it into a little cabin in pretty little spot in the piney woods.“Now along comes Deanna Stiles,” Mac continued, “and she lives in this thing for a while. She also develops a fondness for some dude and out of that we get the emergence of a cute little baby girl, who, because this was Lindbergh’s crate, was named Amelia (after Amelia Earhart). About three years or so after that was when I decided that Amelia ought to have a tune. And that’s how it all happened.”The earliest recording of the tune we’ve found is John McCutcheon's 1982 release on his Fine Times at Our House album for Greenhays.And Whither the Crate?Meanwhile, The Lindbergh Crate has had a moving history of its own (with the accent on the moving….)Its modern chapter began in 1990, when history lover Larry Ross purchased the structure from David Price of Contoocook. Price had received higher offers, but Ross convinced him to sell the crate for $3,000 when he explained his vision to use it as a museum and an educational tool for children. Ross brought the crate from New Hampshire to his property in Canaan, Maine.There, Ross restored the 290-square-foot crate in his backyard, adding a new roof, porches, doors and windows, transforming it into the Lindbergh Crate Museum. Inside, he displayed donated Lindbergh memorabilia, including a bust, letters, tapestries and photographs.For 30 years, Ross hosted an annual “Lindbergh Crate Day” for the community, but during the Covid pandemic, he decided it was time to downsize and sought a new home for the crate. He connected with Morrill Worcester, founder of Wreaths Across America, whom Ross had previously invited to Lindbergh Crate Day. Ross felt Worcester’s location in Columbia Falls, Maine, was suitable because the nonprofit’s mission—”remember, honor, teach”— aligned with the crate’s educational purpose.The Lindbergh Crate was shipped in October 2020 from Canaan and arrived safely at the Wreaths Across America Museum in Columbia Falls. Last year it was moved again to nearby Jonesboro, Maine, where it has been restored by the Worcester family. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Danny Cox and Randy Hamilton brought us this tune a year or so ago and as it matures, it just keeps enriching The Flood’s bloodstream.Not only that, the song is very much on target to be included on the next Flood album when work begins on that project in the months ahead. Give it a listen in this take from a recent rehearsal.About the SongAs noted in an earlier Flood Watch article, “Deep River Blues” is usually associated with the late, great Doc Watson, who included it on his self-titled debut Vanguard Records album back in 1964. The song became so connected to Doc over the years, in fact, that many fans thought it was original with him.However, as we noted, Doc was just 10 years old in 1933 (he was still “Arthel” to his North Carolina family in those early days) when Alabama’s Delmore Brothers released their Victor recording of “I Got The Big River Blues.”Still thinking about that performance 30 years later when he hit the recording studio, Doc fashioned his famed rendition as he thought his hero guitarist Merle Travis would play it, with a heavy emphasis on the thumb thumping out a driving bass line. In the latest Flood rendition, Danny beautifully carries on that tradition.Turn Your (Flood) Radio On!Want to spice up your Friday with a little more from Randy and Danny? The free Radio Floodango music streaming feature has got you covered with randomized playlists of tunes featuring each of them.Click on the graphic above to zip right to the Randy Channel or on the graphic below to give Danny a spin! This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Brooklyn-born Elliott Charles Adnopoz had only just started calling himself “Ramblin’ Jack” in the early 1950s when he came upon a new hero in the wilds of San Francisco.This was a couple years after Elliott had met in his first and most influential mentor — the legendary singer/songwriter/poet Woody Guthrie — whose work and philosophy would shape the 20-something Jack’s long life as an itinerant folksinger.Enter Lone CatA few years after Woody, Elliott rambled all the way across the country and met an extraordinary 60-year-old one-man band by the name of Jesse “Lone Cat” Fuller who was playing on the streets and in the coffeehouses of California’s Bay Area.Jesse, taking a liking to the eager young wanderer, personally taught Jack his best composition — “San Francisco Bay Blues” — just a few years after he had written and recorded it himself.To this day, Jack Elliott — who just last month turned 94 and is still traveling and performing — makes Fuller’s tune a centerpiece in his set list, often introducing it with stories about the song's creator.As the first performer to cover the tune after Fuller’s original recording, Elliott included the song on his 1958 album, Jack Takes the Floor. That track played a crucial role in popularizing “San Francisco Bay Blues” during the burgeoning folk revival of the 1960s. After Jack’s take, the tune entered the canon of many an up-and-coming trouper, from Tom Rush to Richie Havens to Peter, Paul and Mary.Since then, the song has had an extraordinarily diverse number of covers, by Bob Dylan and Jim Kweskin, by Jim Croce and The Weavers, by Hot Tuna and Janis Joplin.Even The Beatles faked a version of it during the Get Back/Let it Be sessions on Jan. 14, 1969. Later John Lennon recorded an unreleased version during his Imagine sessions in May 1971, while McCartney performed it often during his solo concerts in San Francisco. It is still played frequently at Paul’s soundchecks around the world.Eric Clapton performed the song on MTV Unplugged in 1992 during the taping in England. The live album earned six Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year. How Jack Began to RambleBack to Jack, Elliott's life took many turns before he embraced music. Born in New York in 1931, Jack grew up in a family that hoped he would follow his father’s example and go into medicine.But young Elliott was captivated by rodeos and the cowboy life, attending events at Madison Square Garden. At just 15, he rebelled. Running away from home, he joined Colonel Jim Eskew's Rodeo, a journey that took him across the Mid-Atlantic states.Though his rodeo stint lasted only three months, the experience was formative. After he learned guitar and some banjo from a singing cowboy rodeo clown named Brahmer Rogers, Jack was on the path to a music career.Back in Brooklyn, he polished his guitar playing and then started busking for a living. It was just a little later that Jack became a devoted student and admirer of famed folkie Woody Guthrie. Elliott even lived in the Guthrie home for two years.Jack absorbed Guthrie's style of playing and singing so well that Woody himself once remarked, "He sounds more like me than I do."About That NameOne story about Jack is that his iconic nickname didn’t relate so much to his wanderlust as to his storytelling acumen.The late folk singer Odetta always contended that it was her mother who coined the name. "Oh, Jack Elliott,” she was said to have remarked, “yeah, he can sure ramble on!"Jack’s Musical OffspringIn the early 1960s, Elliott toured Britain and Europe with banjo-picking buddy Derroll Adams, recording several albums for Topic Records. In London, the two played small clubs and West End cabarets.Upon returning to the States a couple years later, Elliott found that his albums had preceded him. Suddenly, he had become something of an underground star in the nascent folk music scene around Greenwich Village. Now he was the mentor to newcomers, most notably to a 19-year-old Bob Dylan, who had just hit town. Bob came such a “Ramblin’ Jack” fixture that some started calling him “son of Jack.”Over the years, Jack influenced a generation of musicians, from Phil Ochs and Tom Rush to the Grateful Dead. In the UK, Paul McCartney, Elton John and Rod Stewart all have paid tribute to his style. But it took a few more decades for Elliott to finally get widespread recognition. His 1995 album, South Coast, earned him his first Grammy. In 1998, he received the National Medal of Arts from President Bill Clinton.His long life and career were chronicled in the 2000 documentary, The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack, directed and produced by his daughter, Aiyana Elliott.Back to the SongHonestly, we don’t remember when we first started doing Jesse Fuller’s “San Francisco Bay Blues.” It was back when we were youngsters at those good old folk music parties in the ‘60s. A decade later, the tune was firmly entrenched when The Flood came together. And we were still playing it in 2001 when we recorded our first album, on which it’s the closing track. That was a good call, because we often use this song to close out a show, since it gives everybody in the band one more solo before we call it a night, as you can hear in this take from last week’s rehearsal. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

Some newer immigrants to Floodlandia were surprised by last week’s article celebrating two West Virginia natives — Don Redmond and Chu Berry — who became legendary jazzmen.“I’m sorry,” one of the new friends confided, “but to me the idea of West Virginia conjures up fiddles and banjos. I’ve never thought of it for jazz.”He’s forgiven. Many don’t realize the Mountain State’s musical traditions are more diverse than stereotypes suggest.Meet MaceoIn fact, this year marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of one of the greatest jazz standards of all times, and it was written by an extraordinarily prolific West Virginian who was a major influence in 20th century music.Maceo Pinkard, born in Bluefield, WV, in 1897, the son of a coal miner and a school teacher, was educated at the Bluefield Colored Institute, class of 1913, and wrote his first major song — called “I’m Goin’ Back Home” — the following year. (Today Bluefield State University holds a festival each year to honor of its famous alumnus.)Pinkard wrote hundreds of tunes, including many for stage and screen, his greatest being “Sweet Georgia Brown,” which he published in March 1925. Yes, she might have been a sweet Georgia peach, she was mountain girl at heart. Click here for The Flood’s latest take on the tune from a recent rehearsal.As reported here earlier, the song that would top Maceo Pinkard’s obituary when he died in 1962 at age 65 was co-written with lyricist Ken Casey.Soon after “Sweet Georgia Brown” was composed, it was introduced to the dancing/singing/humming/whistling public by bandleader Ben Bernie. As that nationally known orchestra did much to popularize the number, Pinkard cut Bernie in for a share of the tune's royalties by giving him a co-writer credit. They both could have retired on the royalties.But Pinkard was far from done. He went on to compose iconic tunes such as “Sugar (That Sugar Baby of Mine)” and “Them There Eyes,” the latter famously popularized by the legendary Billie Holiday in 1939. Maceo and DukePinkard also was a mentor to a young Duke Ellington — 20 years his junior — introducing him to New York City’s music publishing industry during the early stages of Duke’s career. That kindness helped Ellington lay the foundation for future success. After meeting at Barron's nightclub in Harlem in the spring of 1926, Pinkard took Ellington downtown to "Tin Pan Alley," the center of the music publishing world on Broadway. There Pinkard arranged for Ellington to have his first meeting at Mills Music. Irving Mills later became Ellington's manager and business partner, a critical boost for the careers of both men.Years later, Ellington said “thank you” to Pinkard by recording some of his early champion’s compositions, including the standards "Sweet Georgia Brown" and "Them There Eyes," highlighting Pinkard's musical legacy. Paul Whiteman and Bix BeiderbeckePaul Whiteman — whose band included Bing Crosby, Hoagy Carmichael, Frankie Trumbauer and Bix Beiderbecke — brought Pinkard in to write material for them. Segregation of the mid-1920s onward thwarted Whiteman’s efforts to hire African-American musicians for his band, but he was determined to play the music of Black composers and Pinkard was his first choice. For instance, in 1927, Pinkard published "Sugar" and, in June 1928, Whiteman's band was the first to record it, scoring a huge hit. Since then, "Sugar" has been done by everyone from Louis Armstrong to Fats Waller (who performed it on the pipe organ). To this day, jazz artists still cover it. Beiderbecke and Pinkard became friends and when Bix went out on his own, Pinkard penned "I'll Be A Friend With Pleasure" for his band (featuring Gene Krupa on drums, Benny Goodman on clarinet and Jimmy Dorsey on sax). Recorded in September 1930, it was among the last numbers that Bix recorded before his death at 28 the following summer.African American West VirginiaPinkard’s story embodies the resilience and creativity of the Black community of West Virginia’s Mercer County. Growing up in Bluefield, Maceo was shaped by the region’s rich heritage, which flourished around institutions like the Bluefield Colored Institute (now Bluefield State University), a hub of African-American culture in the early 20th century.Established in 1895, two years before Pinkard’s birth, Bluefield State emerged as a beacon of opportunity for Black West Virginians. Besides providing access to higher education in the industrialized southern West Virginia, it also was a cultural epicenter, hosting luminaries such as Langston Hughes, Fats Waller and Duke Ellington. During the 1950s and 1960s, Bluefield emerged as a hidden gem on the map of the so-called “Chitlin Circuit,” a national network of venues and businesses that provided platforms for emerging Black jazz and pop musicians during the latter years of institutionalized segregation. More Jazz from the Floodisphere?The Flood constantly expands its repertoire of jazzier tunes from the 1920s onward. To sample a randomized playlist from the cooler corner of the songbag, drop by the Swingin’ Channel of the free Radio Floodango music streaming service.Click here to give it a spin. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com

The last time legendary Wheeling-born saxophonist Chu Berry was in the recording studio, he gave some jazz love to a song written by a fellow West Virginian.The date was Aug. 28, 1941, and the tune — one of the four sides that Berry and his jazz ensemble would record that day for Milt Gabler's Commodore label in New York City’s Reeves Sound Studios on East 44th Street — was “Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You.”The song was still relatively unknown. No one else had recorded it in the dozen years since Piedmont, WV, native Don Redmond wrote it for McKinney's Cotton Pickers to wax in 1929.As discussed here in an earlier article, the Roarin’ Twenties has been good for Don Redman. He was responsible for integrating the rhythmic approach of Louis Armstrong’s playing into arrangements for Fletcher Henderson’s Orchestra. In 1927 Redman was wooed away from Henderson to join McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, the house band at the celebrated Greystone Ballroom in Detroit.When Chu Berry revisited the song in 1941 (to be on the flip side of his version of "Sunny Side of the Street”), it featured ex-Bennie Moten/Count Basie trumpeter Oran “Hot Lips” Page, whose bluesy singing and plunger mute work capped the session.Incidentally, Page recorded it again in 1944, but even more importantly for the song’s legacy (and to Don Redmond’s checkbook) a year earlier the song was also recorded by an up-and-comer named Nat “King” Cole, who took it to No. 1 on the Billboard Harlem Hit Parade where stayed for four weeks.Losing ChuChu Berry would not live to know any of that. Almost exactly two months after the August 1941 recording date, he was on his way to Toronto for a gig with the Cab Calloway Orchestra, with which he had played for four years. Heavy fog made visibility poor, and the car in which Chu was a passenger skidded and crashed into a bridge abutment near Conneaut, Ohio, 70 miles northeast of Cleveland.Berry died three days later from his injuries just a few weeks after his 33rd birthday.Chu Berry was brought back to Wheeling for his funeral. More than a thousand mourners attended, including Cab Calloway and the members of his band who ordered a massive floral arrangement in the shape of a heart.At the funeral, Calloway told mourners Chu had been like a brother to him. The big man had charmed the world, he said, with advanced harmonies and smoothly flowing solos that would influence musicians for generations to come. “Chu will always be a member of our band,” Cab said. “He was the greatest.”Berry’s RootsBorn in Wheeling in 1908, Leon Brown Berry took up the saxophone as a youngster after being inspired by the great tenor man Coleman Hawkins. Berry went on to model his own playing after Hawkins, who would later be quoted as saying, “Chu was about the best.” By the time of his 27th birthday, Chu had moved to New York where he worked with Bessie Smith, Lionel Hampton, Count Basie and others.Eventually, he became the featured sax player with the hottest jazz band of the day, Cab Calloway’s legendary Cotton Club Orchestra. In 1937 and 1938, he was named to Metronome Magazine’s All-Star Band. Younger contemporaries — notably Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie — almost certainly heard Berry up close and personal at the now-legendary Monday night jam sessions at Minton’s Playhouse in New York City, gatherings widely credited for the development of the bebop in the mid-1940s.Famously, in 1938 Parker — 14 years younger than Chu — named his first child Leon in tribute to Berry.And the Nickname?Multiple explanations have been given as to how Leon Berry got his nickname. Music critic Gary Giddins has said Berry was called “Chu” by his fellow musicians either because of his tendency to chew on his mouthpiece or because at one time he had a Fu Manchu-style mustache. Both stories work; take your pick.Our Take on the TuneJoining The Flood repertoire, some songs fit in right away, while others, like this one, need a little time to settle in, but when they do, wow — they’re as comfortable as an old shoe. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com