Discover The Nuzzo Letter

The Nuzzo Letter

The Nuzzo Letter

Author: James L. Nuzzo

Subscribed: 0Played: 1Subscribe

Share

© James L. Nuzzo

Description

53 Episodes

Reverse

On July 10, 2025, the Pew Research Center published results from its poll of 5,085 American men and women titled, “Americans’ Views on Who Influences Health Policy and Which Health Issues to Prioritize.”In one part of the poll, participants were presented with a list of eight health issues and asked to indicate which issues they believe are a “major problem,” “minor problem,” or “not a problem at all.” The results can be seen in the figure below.Roughly 80-85% of poll participants reported a belief that cancer, overweight and obesity, heart disease, and opioid addiction are “major problems.” Alzheimer’s disease came in fifth on the list with 64% of Americans saying it is a “major problem,” followed by loneliness at 55%, bird flu at 26%, and measles at 25%.The Pew Research Center also split the results by political affiliation of poll participants. On average, the same proportions of Democrats and Republicans agreed that cancer, overweight and obesity, heart disease, and opioid addiction are “major problems.” This consensus across party lines is encouraging to see. However, for loneliness, bird flu, and measles, more Democrats than Republicans reported a belief that these are “major problems.”Later in the poll, the Pew Research Center asked participants about the importance of the federal government in overseeing certain areas of healthcare. Six areas were presented, including testing drug safety, tracking the spread of contagious diseases, investigating health insurance fraud, making rules about food labels, and developing programs that place doctors and nurses in rural communities.The other healthcare area that the Pew Research Center asked about was women’s health. Specifically, Pew asked participants how important they thought it was for the federal government to “study health issues that affect women and girls.”The results to this question, which can be seen in the figure below, were as follows:* 45% of Americans said it is extremely important for the federal government to study health issues that affect women and girls.* 32% of Americans said it is very important for the federal government to study health issues that affect women and girls.* 18% of Americans said it is somewhat important for the federal government to study health issues that affect women and girls.* 5% of Americans say it is not at all important for the federal government to study health issues that affect women and girls.In the text of the report, the Pew Research Center also revealed a sex difference in belief about the federal government studying girls’ and women’s health. Fifty percent of women and 41% of men said that they believe it is extremely important for the federal government to study health issues that affect women and girls – a 9% difference between the sexes.The difference between Democrats and Republicans was even larger. Fifty-nine percent of Democrats and 32% of Republicans said that they believe it is extremely important for the federal government to study health issues that affect women and girls – a 27% difference between the political parties.Curious minds are likely to wonder how poll participants’ views on the federal government studying women’s health compare to their views on the federal government studying men’s health. For example, did the male and female participants demonstrate the same 9% sex differential as they did when asked about women’s health? Was the 27% differential between Democrats and Republicans also replicated when the poll participants were asked about men’s health?Unfortunately, we do not know the answers to these questions, because the Pew Research Center did not ask poll participants about their opinions on the role of the federal government in studying boys’ and men’s health issues. This omission was particularly strange considering that more males than females die from four of the top five health problems that Pew asked about earlier in their poll. These four health problems are cancer, diseases of the heart, obesity, and opioid and other drug-related overdoses. As shown in the graph below, males comprise 52.7% of all deaths from cancer, 55.3% of deaths from disease of the heart, 53.8% of deaths from obesity, and 69.6% of deaths from drug overdoses.When one also considers, for example, the greater number of male than female suicides, homicides, fatal occupational injuries, unintentional drownings, and alcohol-induced deaths, which culminate in a significantly shorter life expectancyfor American males than females, Pew’s omission of men’s health from the poll is even more perplexing.Pew’s omission of men’s health from the poll might have been purposeful. However, their omission might also reflect a genuine lack of awareness that coincides with an inability to connect specific epidemiological results, which, together, build the broader concept of men’s health. Within public health and biomedical research circles, this lack of conceptualization of men’s health as a broad healthcare area can be seen in the graph below, which I published in a paperin 2020. The graph shows the number of times the phrases “men’s health” and “women’s health” appear in the titles or abstracts of research articles indexed in PubMed. Between 1970 and 2018, the phrase “men’s health” appeared in the titles or abstracts of 1,555 articles indexed in PubMed, whereas the phrase “women’s health” appeared in the titles or abstracts of 14,501 articles indexed in PubMed – an approximate 10-fold difference.Moving forward, polling organizations who survey public opinion about health issues affecting Americans ought to ask about women’s and men’s health. Both areas are important and warrant attention. In terms of broad healthcare policy, giving asymmetrical attention to one sex over the other is neither just nor is it a healthy long-term strategy for a flourishing society. As Dr. Warren Farrell says, “When only one sex wins, both sexes lose.”Let us hope that in future polls we will finally learn where the general public stands regarding their views on the broad area of men’s health. Remarkably, after all the billions of dollars poured into health research and polling over the years, we still do not have clear answers to such simple questions.Related Content at The Nuzzo LetterSUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTERIf you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.Thanks for reading The Nuzzo Letter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit jameslnuzzo.substack.com

The United States (U.S.) Office of Research on Women’s Health was created within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1990. Organizationally, the Office is positioned within the Office of the Director of the NIH. The original goals of the Office of Research on Women’s Health were:“(1) to strengthen, develop, and increase research into diseases, disorders, and conditions that are unique to, more prevalent among, or more serious in women, or for which there are different risk factors for women than for men;(2) to ensure that women are appropriately represented in biomedical and biobehavioral research studies, especially clinical trials, that are supported by the NIH; and(3) to direct initiatives to increase the number of women in biomedical careers.”All three goals have been achieved. The goal of increasing the number of female participants in clinical research trials was based on the claim that women were historically excluded from clinical research trials. This claim was largely unsubstantiated at the time that it was made, and numerous studies have since shown that women are not underrepresented as participants in medical research. In fact, reports published by the Office of Research on Women’s Health show that women have comprised 55-60% of participants in NIH-funded trials for the past three decades.The notion that women have been “underrepresented” in research trials has also been historically linked to the idea that women’s health research has been “underfunded.” This claim is also untrue.First, as shown in the graph below, the Office of Research on Women’s Health has had its own budget for supporting and coordinating women’s health research since 1991. That budget has totalled approximately $1.3 billion over the past 35 years.Second, the amount of money that the NIH expends on women’s health research across all its institutes is significantly greater than the amount it expends on men’ health research. As shown in the graph below, approximately 81% of the NIH’s research funding is not sex-specific. However, of the remaining funding that is sex-specific, women’s health receives approximately 13% each year, whereas men’s health receives approximately 6% each year. This amounts to approximately $4.1 billion each year for women’s health research and $1.8 billion per year for men’s health research.Given the substantial amount of money invested into women’s health research, and the more-than-adequate representation of females as participants in NIH-funded clinical trials, the Office of Research on Women’s Health has presumably also achieved its goal of strengthening, developing, and increasing research into diseases, disorders, and conditions that are unique to or more prevalent among women. If such goals have not been achieved, then taxpayers are owed an explanation for how this could be possible given the billions of dollars that has been invested into women’s health research.The third goal of the Office of Research on Women’s Health was to increase the number of women in biomedical careers. This goal has long since been achieved. Women comprise the majority of students who graduate from U.S. universities with degrees in health-related fields. Greater numbers of female than male graduates are now observed in many health and medical fields including public health, healthcare administration and management, pharmacy, medicine, dentistry, optometry, physical therapy, occupational therapy, nursing, and psychology. In 2021-22, women comprised 80% of university graduates across all health-related fields.Given all of this information, one might think that women’s health advocates would want to celebrate the achievements of their original goals. After the celebration finishes, they might even take a moment to consider whether public health attention has gone too far in the female direction, given that male life expectancy is 5.3 years shorter than female life expectancy, and no Office of Research on Men’s Health has ever been created.As Dr. Warren Farrell says, “When only one sex wins, both sexes lose.”Unfortunately, no “mission accomplished” celebration seems to have ever occurred, and Dr. Farrell’s conceptualization still does not seem to be understood by many individuals who work within the academic and public health sectors.National AcademiesIn December of 2024, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine – with the input of 17 committee members, two fellows, 10 study staff, eight consultants, and 17 reviewers – published a report titled, “A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health.” The report was also subsequently covered in a piece in Science titled, “NIH needs a new institute for women’s health research, expert panel says.”The National Academies are not a government agency. According to their website, “The National Academies provide independent, objective advice to inform policy with evidence, spark progress and innovation, and confront challenging issues for the benefit of society.”From the National Academies’ website, one also learns of their vision, mission, and core values. Their vision is a “nation and a world that rely on scientific evidence to make decisions that benefit humanity.” Their mission is to “provide independent, trustworthy advice and facilitate solutions to complex challenges by mobilizing expertise, practice, and knowledge.” Their core values are “Independence, Objectivity, Rigor, Integrity, Inclusivity, Truth.”Here, my first aim is to introduce the recommendations made by the National Academies regarding the future of the NIH and women’s health research. My second aim is to highlight the flaws in the National Academies’ report and suggest that these flaws are evidence of the National Academies’ failure to live up to its own professed vision, mission, and core values.National Academies’ Recommendation #1: NIH Organizational Structure“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should form a new Institute to address the gaps in women’s health research (WHR) and create a new interdisciplinary research fund. Furthermore, NIH leadership should expand its oversight and support for WHR across the Institutes and Centers (ICs). Congress should appropriate additional funding to adequately support these new efforts.”Under this recommendation, the National Academies further specify that they believe the Office of Research on Women’s Health should be elevated to a position of an independent institute within the NIH and that the Office should be given its own budget of at least $4 billion over the first five years. In addition to this separate budget, the National Academies recommend that Congress establish a new separate fund for women’s health research through the Office of the NIH director. They state that this fund should equal $11.4 billion over the first five years.National Academies’ Recommendation #2: Oversight and Tracking Investment into Women’s Health Research“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should reform its process for tracking and analyzing its investments in research funding to improve accuracy for reporting to Congress and the public on expenditures on women’s health research (WHR).”Under this recommendation, the National Academies suggest that the NIH is not currently categorizing women’s health research accurately and that a modified categorization system is necessary to better summarize how much money the NIH expends on women’s health research.National Academies’ Recommendation #3: Prioritizing Women’s Health Research“The Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) should develop and implement a transparent, biennial process to set priorities for women’s health research (WHR). The process should be data driven and include input from the scientific and practitioner communities and the public. Priorities of the director and the Institutes and Centers (ICs) should respond to the gaps in the evidence base and evolving women’s health needs.”Under this recommendation, the National Academies also state that most NIH Institutes and Center have plans that “rarely mention women’s health” and that “significant gaps in WHR at NIH are the result of the substantial historical underrepresentation, lack of accountability, inadequate funding, and dearth of comprehensive research that have long characterized this field. Decades of insufficient focus have resulted in critical knowledge deficits and disparities in health outcomes for women.”National Academies’ Recommendation #4: Careers in Women’s Health Research“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should augment existing and develop new programs to attract researchers and support career pathways for scientists through all stages of the careers of women’s health researchers.”Under this recommendation, the National Academies discuss a loan repayment program for researchers who investigate women’s health, expansion of NIH support for early- and mid-career researchers who study women’s health, and additional special considerations for researchers who apply for women’s health research grants.National Academies’ Recommendation #5: Expanding the Women’s Health Research Workforce“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should augment existing and develop new grant programs specifically designed to promote interdisciplinary science and career development in areas related to women’s health. NIH should prioritize and promote participation of women and investigators from underrepresented communities.”Under this recommendation, the National Academies discuss expanding the following centers and programs: the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) Program, the Specialized Centers of Research Excellence (SCORE) on Sex Differences, the Women’s Reproductive Health Research (WRHR) program, and the Research Scientist Development Program (RSDP).National Academies’ Recommendation #6: Women’s Health Expertise on Grant Review Panels“The National Ins

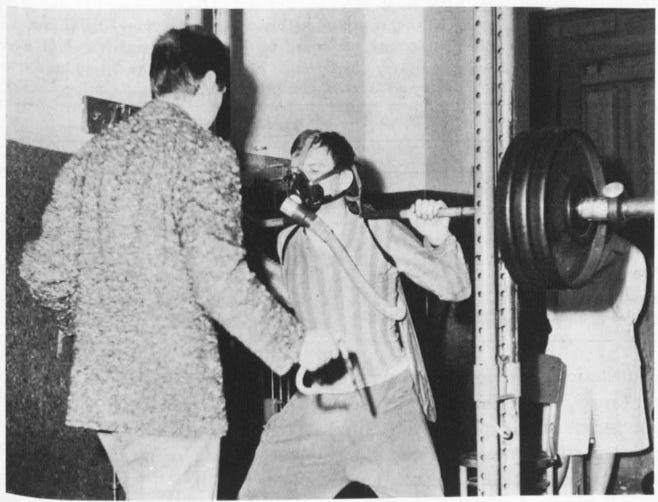

On May 31, 2024, I published an essay titled, “History Didn’t Start at Title IX.” In the essay, I challenged the common assumption that women were historically excluded from early research about physical exercise. I explained that a reasonable degree of female participation can be expected in early physical exercise research because much early research on exercise would have been conducted in the fields of physical therapy and physical education. Those two fields pre-dated exercise science, had their own journals, and had large representations of female professors and students.In the essay, I included photographs from papers published in these journals that showed girls and women participating in this early research. Thus, the essay provided some initial evidence that girls and women were participants in early research studies that pertained to physical exercise. More recently, I made this analysis more formal, and I expanded upon it. The results were recently published in the journal Advances in Physiology Education in a paper titled “Bibliometric guides to early physical exercise, education, and rehabilitation research on girls and women.Here, my purpose is to briefly explain the methods and results of this new research and reiterate why the findings are important.My paper had two aims. The first aim was to create a bibliometric list of papers that included photographs of girls and women participating in physical exercise, education, and rehabilitation research prior to 1980. The second aim was to create a bibliometric list of papers that included data or commentary on the menstrual cycle within physical exercise, education, and rehabilitation contexts.To identify photographs of female participants, I searched the entire archives of three of the most important journals in exercise research history: Research Quarterly (from 1930 to 1979), Journal of Applied Physiology (from 1948 to 1979), and Medicine and Science in Sports (from 1969 to 1979). I then searched my own personal digital archives, which included papers published in other journals. These other journals were not searched entirely because their full archives were not accessible to me.The search for papers about the menstrual cycle and exercise was more lenient. These papers were noted and filed during the search for photographs and while conducting research for other historical projects.Both of these historical analyses are to be considered exploratory because not all journal archives were fully searched. Thus, more historical photographs and more data and commentary on the menstrual cycle and physical exercise exist beyond what I published in the two bibliometric lists.The first bibliometric list consists of 95 papers, published between 1907 and 1979, that included 306 photographs of girls and women participating in physical exercise research. These photographs depicted girls and women performing various tests, and descriptions of the photographs are provided in the paper. The girls and women were most commonly photographed performing or undergoing tests of muscle strength, motor skill learning, body composition, or posture. Example photographs can be seen in my previous post. A sample of the first 15 papers on the list is shown below.This list parallels the bibliometric list that I published in the Journal of Men’s Health regarding papers published before 1980 that included photographs of male research participants.The second bibliometric list consists of 77 papers, published between 1876 and 1979, that included data or commentary on the menstrual cycle or menstrual symptoms within physical exercise, education, and rehabilitation contexts. Of the 77 papers, 22 papers were “either reviews or commentaries about the menstrual cycle, consensus statements about women and exercise that included a comment or section about the menstrual cycle, or original papers or review papers that included brief ancillary comments about the menstrual cycle.” The other 55 papers were original research with new data related to the menstrual cycle. This included the following:1) menstrual symptoms in high school and university students as identified in physical examinations conducted as part of physical education class;2) menstrual symptoms in athletes and nonathletes as identified by questionnaires;3) relationships of menstrual symptoms and abdominal strength and other aspects of physicalfitness as measured by laboratory techniques;4) the impact of oral contraceptives on physical activity and physiological responses to exercise as measured via ecological or laboratory tests.A sample of the first 17 papers on this list is shown below.The two bibliometric lists further disprove claims that women were historically excluded from research and that early researchers were not interested in women’s health. Contemporary researchers who conduct audits of female representation typically do not examine journals that are historically linked to exercise science and published in the early- and mid-1900s. Consequently, the exact percentages of male and female participants in early research on exercise, health, and medicine is not known. Moreover, when papers published before 1980 are omitted from audits, and thus studies in the two bibliometric lists are not identified, this gives readers an impression that early researchers, many of whom were femalephysical educators and therapists, were disinterested in women’s health, including in the menstrual cycle. But this assumed disinterest is a myth.My latest pre-printed paper further challenges this myth. In the paper, I tallied the number of male and female participants in all studies published in Research Quarterly between 1930 and 1979. The results revealed that after two large military studies of male participants were excluded as outliers, girls and women comprised 40% of all research participants. That is hardly evidence “widespread exclusion” of women from research trials, disinterest in women’s health, or bias or discrimination against women.My hope is that these new historical analyses will be used by educators to teach themselves and their students about the history of male and female participation in early exercise and exercise-related research. This history is nuanced and is not explained by false blanket assertions such as women being historically excluded from research, or that early researchers were disinterested in women’s health issues. In fact, one interesting aspect of this nuanced history, which my latest pre-printed paper confirms, is that participant sex correlates with researcher sex. Thus, one reason why studies within some areas might show greater male than female participation is because of greater male than female researcher productivity. Consequently, if contemporary female exercise scientists are unhappy with the amount of data this is available on women, then they can resolve this by spending hours in the laboratory collecting and analysing data and then publishing the results, as that is what many men have been doing throughout the history of science.Related Content at The Nuzzo LetterSUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTERIf you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.Thanks for reading The Nuzzo Letter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work. This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit jameslnuzzo.substack.com

Just when you thought the unrelenting attacks on men from academia could not get any worse, they have.In the journal Psychology of Men & Masculinities, the concept “mankeeping” was recently introduced by Angelica Ferrara and Dylan Vergara of the Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University. The title of their paper was, “Theorizing Mankeeping: The Male Friendship Recession and Women’s Associated Labor as a Structural Component of Gender Inequality.”“Mankeeping” adds to the litany of words and concepts that academics have created to ridicule the male sex. Other examples include “toxic masculinity,” “male privilege,” “mansplaining,” “manels,” and “manferences.”Ferrara and Vergara defined “mankeeping” as “the labor that women take on to shore up losses in men’s social networks and reduce the burden of men’s isolation on families, the heterosexual bond, and on men.” And, they added:“[m]ankeeping is best conceived as a mechanism through which women support and bolster men’s levels of social support.”According to Ferrara and Vergara, “mankeeping” is a form of women’s unpaid and unequal emotional care work. Some examples of this “invisibilized labor” provided by the authors included the following:* A woman suggesting that her husband reconnect with old friends* A girlfriend facilitating a group outing to help her boyfriend bond with other men* A wife sending a husband on a “man date” with other men* A mother suggesting to her son that he contact his friends* A woman reminding a man to join a men’s group* A woman “checking in on her husband’s emotional state after learning he has had a stressful day at work”* A wife helping her husband “articulate his own feelings through a process of deciphering limited social and emotional cues”And what are the fundamental causes and final consequences of “mankeeping”? According to the authors, “mankeeping” is “a component of patriarchy’s persistence within the heterosexual bond, asserting that an unequal distribution of social support is part and parcel of the everyday social reproduction of gender inequality.”To summarize, the flow of ideas underlying Ferrara and Vergara’s concept of “mankeeping” goes as follows:* Increased numbers of men are lonely or social disconnected;* Women have to pick up the slack in men’s lack of social relationships;* Women perform unpaid labor when serving as social and emotional facilitators for men;* Women’s social and emotional labor is unpaid and unequal and therefore it reinforces the patriarchy and exacerbates gender inequality.Here, my purpose is to highlight various flaws with Ferrara and Vergara’s concept of “mankeeping.”Lack of Empathy for MenThe first issue with Ferrara and Vergara’s concept of “mankeeping” is that it lacks empathy for men. To the extent that men are lacking healthy social relationships, the focus of a paper in a “men and masculinities” journal ought to be the causes and solutions of men’s mental and emotional health issues. Yet, in predictable gynocentric fashion, the authors made the story about women.“Men and masculinities scholars must interrogate how the effects of these trends, while troubling for men themselves, may cascade beyond men.”In other words, men’s health is merely a launching pad for discussing additional ways that society can accommodate women.To further illustrate the degree to which the authors had no interest in discussing men’s health, one need only look at the incoherent sentence where the authors placed the phrase “male issue” in quotes. This was done, presumably, to mock or minimize the notion that men’s health, not gender inequality, be the main point of discussion.“To conceptualize men’s thinner social networks as a mere symptom of gender inequality, or a “male issue,” rather than a structural component of how patriarchy is upheld and reproduced, is to miss a critical avenue for social change. Our concept of mankeeping presents one mechanism through which men’s social isolation could reproduce existing inequalities…”Women as Social Beings and CarersAnother issue with Ferrara and Vergara’s concept of “mankeeping” is that it seems to assume that men and women would, if unchained from the restrictive patriarchy, exhibit near-identical social behaviors and indicators and that women would not be more inclined than men to want be emotional carers. But on what grounds are such assumptions made, given the substantial research literature on sex differences in preferences, interests, and behaviours?Sex differences in vocational interests is one example. Women are more likely than men to prefer working with people than things, whereas men are more likely than women to prefer working with things than people. This is why more women than men study and work in fields like psychology and social work. In fact, psychology and social work are also fields that involve providing emotional care to others (i.e., “mankeeping” or “womankeeping”) and thus also illustrate the greater female than male inclination for wanting to provide emotional care to both men and women.Other lines of evidence also point to women being naturally more social than men. The American Time Use Survey consistently shows that women spend more time than men “socializing and communicating,” including in face-to-face interactions, hosting or attending social events, and communicating with others via the telephone and internet. A recent Pew poll of over 6,000 American residents also found that women were more likely than men to keep in touch with friends by phone, text, and social media.Thus, women appear to acquire much value and meaning out of life from frequent social interactions. Many of these interactions will involve emotional care for others. These sex differences are likely biologically driven. Results from a study in hamsters suggest that the average female and male brain respond differently to social interactions, with oxytocin playing a key role in the heightened female response.Relationship Trade-OffsFerrara and Vergara’s failure to reference the biological basis of sex differences then leads to lack of acknowledgement of trade-offs in relationships. Their presentation of male-female relationships was one-sided: the woman does the vast majority of the care work and apparently the man offers very little in return.A man and a woman both bring unique attributes to a partnership. The man could be any number of things: funny, caring, rich, intelligent, a hard worker, physically attractive, friendly, reliable, the father of their children, good at fixing things around the house, good at making the woman feel safe and protected, etc. These characteristics would all be reasons why his female partner would want to care for him. It is in her self-interest to do so. Without him, she loses her greatest value.Yet, instead of discussing trade-offs in partnerships, and the unique currency that men bring to the relationship exchange, Ferrara and Vergara presented a story in which women’s emotional care work is presented independent of the larger context of the natural given and take of romantic partnerships. For example, whereas a wife might take on more of the unpaid household work, her husband might take on more of the paid work outside the home (often at risk to his health), such that when hours of all work are summed, men and women contribute roughly equally to the partnership. Thus, to the extent that women might be providing a disproportionate amount of emotional care, men are likely providing their own unique type of care at a disproportionate level. In fact, the husband’s job might be paying for all of his wife’s healthcare!Women’s Perceptions of Emotional CareFerrara and Vergara also do not account for women’s perception of how much “mankeeping” that they think they need to perform versus how much care a man actually needs or desires. A wife who is constantly worrying about some aspect of her husband’s life might be doing so unnecessarily. She might think that she needs to repeatedly call or text him, but the man might find this excessive. Compared to men, women worry more, experience greater levels of anxiety, and exhibit a greater overall neurotic profile. Thus, by seemingly taking women’s word for it, Ferrara and Vergara, have assumed that all female emotional labor is necessary. It may be; it may not be.Lesbians and Men Who Carry the Emotional LoadAnother issue with the concept of “mankeeping” is that “womankeeping” also exists. Ferrara and Vergara eventually admitted this when they said: “there are many relationships in which men carry out an outsized portion of emotion work on behalf of women and other genders.”Nevertheless, the authors did not explore the topic of “womankeeping” in any detail. One example that is familiar to me, based on previous research that I helped conduct, is Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is a physically, mentally, and emotionally debilitating condition. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is more prevalent in women than men. In the United States, approximately 1.7% of women and 0.9% of men have received a diagnosis of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Consequently, who serves as the primary physical and emotional carer for heterosexual women who live with this condition? Husbands.Ferrara and Vergara also conveniently ignored lesbian relationships. They did not explain if “mankeeping” exists in these relationships, and assuming that an imbalance of emotional care does exist between lesbians, the authors did not explain if this somehow also reinforces the patriarchy and gender inequality.Men’s Social Networks Must be Feminist-Approved or Else…According to Ferrara and Vergara, a root cause of “mankeeping” is men’s declining social networks. Therefore, a solution to “mankeeping” is men engaging in more social activities. However, men finding genuine fraternal connection through increased engagement with their own social networks is often viewed by feminists as a threat to feminism. Thus, Ferrara and Ve

In September of 2023, actor Kevin Sorbo, famous for his starring role in the 1990s television show “Hercules,” wrote an article for Fox News titled, “Let’s make Hollywood manly again.”In his article, Sorbo argued that modern Hollywood poorly portrays men and masculinity and thus does not give boys positive role models to look up to.In addition to critiquing Hollywood for frequently portraying fathers as “bumbling, useless idiots,” who do not contribute to their families or communities in positive ways, and who are “the butt of every woke Hollywood jab,” Sorbo also criticized Hollywood for exposing audiences to a continuous stream of bold and confident women who “upstage passive men who recede quietly into the background.”I welcomed Sorbo’s article. Like many other movie watchers, I have grown tired of Hollywood’s trends over the past 5 to 10 years. Such trends include the push for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in casts and crews, the forced Woke messaging, the glorification of nihilism, the moral ambiguity in story lines, and the seemingly endless numbers of remakes of movies whose original versions were perfectly fine.Thus, I commend Kevin Sorbo for his article. It was a timely, thoughtful, and largely accurate critique of one of society’s most influential institutions.Nevertheless, I disagree with part of Sorbo’s position. In two sentences, Sorbo included the concept “sacrifice” as part of his definition of masculinity. Thus, Sorbo believes that Hollywood needs to show more male sacrifice.“America today needs warriors; protectors; responsible and committed fathers…We need men who will raise their kids, defend their homes, provide for their families, and serve self-sacrificially…”Then, Sorbo concluded his article by stating the following:“It’s time for the world’s entertainment capital to reintroduce good men: men who love their wives and children, protect them, fight for what’s right, and speak up for the powerless. Men who, above all, have overcome their own selfish desires and are free to put others first. After all, that’s the most masculine thing any man can do.”My purpose here is to highlight why Sorbo’s definition of masculinity based on the concept of “sacrifice” is flawed.Sorbo suggested that sacrifice and the ridding one’s selfish desires is peak masculinity. Sorbo implied that raising one’s kids, defending one’s home, and providing for one’s family are sacrifices. But why view fatherhood and masculinity in this way? Why frame these responsibilities and commitments as “sacrifices”? Does a man not receive any personal boost to his ego or self-esteem when he completes these acts successfully?To “sacrifice” something, according to novelist-philosopher Ayn Rand, means “the surrender of that which you value in favor of that which you don't” or “the surrender of a greater value for the sake of a lesser one or of a nonvalue.”Thus, Sorbo’s view – that “sacrifice” is fundamental to masculinity and that selfishness is counter to masculinity – is problematic. It teaches boys and men not to value their own needs – i.e., themselves. It tells them that their lives hold no intrinsic worth, and that their value is predicated on serving the needs and desires of others. The male sex is mere cannon fodder.The alternative to Sorbo’s framing of masculinity through the collectivist framework and the ethics of altruism is to frame it through the ethics of rational selfishness, which simply means to pursue one’s values in accordance with one’s long-term interests.Unfortunately, through much of history, the word “selfishness” has been battered and mischaracterized by writers, including Sorbo, who conflate the concept with disregard of others or narcissism, which is a sort of pathological version of selfishness.Ayn Rand explained this problematic framing of selfishness in her book, “The Virtue of Selfishness”:“The meaning ascribed in popular usage to the word "selfishness" is not merely wrong: it represents a devastating intellectual "package-deal," which is responsible, more than any other single factor, for the arrested moral development of mankind.In popular usage, the word "selfishness" is a synonym of evil; the image it conjures is of a murderous brute who tramples over piles of corpses to achieve his own ends, who cares for no living being and pursues nothing but the gratification of the mindless whims of any immediate moment.Yet the exact meaning and dictionary definition of the word "selfishness" is: concern with one's own interests.This concept does not include a moral evaluation; it does not tell us whether concern with one's own interests is good or evil; nor does it tell us what constitutes man's actual interests. It is the task of ethics to answer such questions.”Thus, acting selfishly simply means pursing one’s own rational values. These values can certainly include loving one’s family, as Rand also explained:“Concern for the welfare of those one loves is a rational part of one's selfish interests. If a man who is passionately in love with his wife spends a fortune to cure her of a dangerous illness, it would be absurd to claim that he does it as a "sacrifice" for her sake, not his own, and that it makes no difference to him, personally and selfishly, whether she lives or dies. Any action that a man undertakes for the benefit of those he loves is not a sacrifice.”In other words, Sorbo was incorrect to add “sacrifice” to his definition of masculinity, because all the other features of masculinity that he described generally constitute a man acting in his own selfish interest. For example, part of becoming a warrior and protector involves continually training one’s body and mind to take on life’s challenges. Such training is a selfish act because it aids in one’s own survival. Also, raising one’s kids is not a sacrifice if a father feels joy watching his sons or daughters develop into good citizens and pursue and achieve their own selfish values.Sorbo seems to have in mind the sort of man who consumes copious amounts of drugs or alcohol to feel momentary pleasure. Yet, such men are not selfish. They are not acting in their own rational, long-term interests. Truly selfish men value their lives too much to damage their health in such ways. In fact, part of what drives some men to participates in these problematic behaviors and short-term “solutions” to their problems is their own lack of self-esteem and self-worth.To understand that selfishness does not conflict with the healthy manifestation of masculinity, Sorbo might consider watching the movie Taken, starring Liam Neeson.In Taken, Neeson plays Bryan Mills – a former Green Beret and retired agent of the CIA. Mills is divorced from his wife, and he is trying to work on his relationship with his only child, Kim, who is 17 years old. Kim decides that she wants to visit Paris with one of her girlfriends. Mills, based on his years of knowledge and experience working in the military and CIA, expresses concerns about Kim going to Paris without supervision. Reluctantly, and after being pressured by both Kim and his ex-wife, Bryan agrees to let Kim travel overseas.Interestingly, this part of the movie depicts a father’s love through his protectiveness. However, this protectiveness was ridiculed by both the ex-wife and the daughter, and both characters suffered as a result of not listening to dad, because on the day that Kim and her friend arrive in Paris, they are kidnapped and sold into an Albanian sex trafficking ring. Upon learning of this devasting news, Bryan flies to Paris to search for his daughter, her friend, and the thugs who kidnapped them.During the search, Bryan risks his life many times, and Bryan took these risks because of his profound and selfish love of his daughter. Bryan knew that his life would be happy and more fulfilled if Kim were part of it. Thus, Saving Kim’s life was not only in Kim’s best interest, it was in Bryan’s best interest, too.Per romantic art, Bryan overcame many physical and mental challenges in warding off evil to save Kim. In doing so, Bryan reaffirmed his distinct role as Kim’s father, and we are led to believe that seeing her grow and flourish will bring Bryan many years of joy. As Ayn Rand said, “[c]oncern for the welfare of those one loves is a rational part of one's selfish interests.”To conclude, Kevin Sorbo deserves credit for writing an article that argues for the healthy and entertaining portrayal of men and masculinity. His concern that contemporary movies lack in positive role models for boys is correct, and if Hollywood adopted even a morsel of Sorbo’s suggested characterizations of men in films, we all would have more engaging and emotional-moving movies to watch.Nevertheless, Sorbo’s view that “sacrifice” is fundamental to masculinity is problematic. Perhaps this is a problem of semantics. Perhaps Sorbo agrees that boys should be taught to value their own lives and pursue their own values and interests. Perhaps Sorbo simply misused the term “sacrifice.” Either way, semantics are important, and Sorbo’s sloppy use of this language illustrates the ongoing confusion about “selfishness” and “sacrifice” that Ayn Rand highlighted decades ago.One reason why misuse of the term “sacrifice” is concerning is because it leads to the mislabelling of rationally selfish acts as sacrificial ones. The danger then is concept creep or concept realignment, wherein actual sacrifices – things that are detrimental to a man’s wellbeing – become justified, because they have been conceptually lumped together with things that are in a man’s best interest. In such cases, the concept “sacrifice” is given underserved credit, as it was in Sorbo’s article. Moreover, framing a man’s role in a relationship as a continuous stream of “sacrifice” probably does not sit well with many men when labelled as such, and use of this nomenclature coupled with the expectation of actual male sacrifice may in fact, underlie some of today’s relational and fa

“This is feminist economic policy in action.”Chrystia Freeland, Canadian Deputy PM, Minister of Finance (Budget 2022)Investigations into the way that government’s allocate money into health research is important, because taxpayers should know how their money is being used and if that use aligns with broader societal interest and medical need.At The Nuzzo Letter, I have previously shown that substantial differences exist in funding of men’s and women’s health research in Australia and the United States (U.S.). In Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) invests about five times more money into women’s than men’s health research (graph below). In the U.S., the National Institutes of Health (NIH) invests about 14% of its annual research budget into women’s health and 6% of its annual research budget into men’s health (graph below). Obtaining the funding data from Australia was not difficult, as the NHMRC publishes these data openly on its website in a small table. Obtaining the funding data from the U.S. was more cumbersome, as it required downloading annual reports published by the Office of Research on Women’s Health and extracting and organizing the relevant data. Nevertheless, so long as one was aware of the Office’s reports and where to find them, graphing the data was still possible. Canada is a different story.Canadian Institutes of Health ResearchCanada’s main government funding body for health research is the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. This government agency was established in 2000 and is similar to the NHMRC in Australia and the NIH in the U.S. It consists of 13 institutes that operate separate from Health Canada. One of the institutes is the Institute of Gender and Health. This institute is the Canadian equivalent of the NIH’s Office of Research on Women’s Health in the U.S.Here, my aim was to identify, extract, and summarize data from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to explore whether the sex differences in health research funding that exist in the U.S and Australia also exist in Canada. However, in pursing this aim, I was unable to find annual reports from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research where financial allocations for men’s and women’s health research are itemized. Consequently, I was unable to generate a graph similar to those that I have created for the U.S. and Australia. Instead, to get a general sense of such funding allocations, I had to rely on a hodgepodge of spreadsheets, reports, and press releases scattered across websites of various agencies within the Canadian government.The National Women’s Health Research Initiative (NHWRI)Women and Gender Equality Canada (WAGE) is a department in the Canadian government and is separate from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. However, in 2021, WAGE and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research joined forces to create the National Women's Health Research Initiative (NWHRI).According to the Canadian government, the aim of the Initiative is to “advance a coordinated research program that addresses under-researched and high-priority areas of women's health and to ensure new evidence improves women's, girls’, and gender-diverse people's care and health outcomes.”In 2021, the Canadian government announced it would invest $20 million over five years into the Initiative.The Initiative is composed of two funding streams. The first is the Pan-Canadian Women's Health Coalition, which has been described by the Canadian government as “virtual hubs across Canada linked through an overarching coordinating centre.” In October 2022, the Canadian government announced that $8.4 million was available for 10 grants that would create the Coalition. To receive one of these grants, applicants were required to incorporate the following themes into the hub’s activities: engagement of women with lived or living experience; inclusion of indigenous peoples; inclusion of the concepts equity, diversity, and inclusion; and inclusion of sex- and gender-based analysis. Ten hubs were subsequently created from these grants, and the projects undertaken by each hub are now listed online.In June 2023, another funding opportunity for one grant of up to $1.2 million was announced to create the Coordinating Centre that “together with hubs will work to mobilize new and existing knowledge in women's health into effective, gender-sensitive, and culturally appropriate women's health services across Canada.” This additional funding helped to finish the overall aim of the Coalition, which was to create a central source of scientific and clinical information regarding the latest developments in women’s health (but not men’s health).The second part of the National Women’s Health Research Initiative is the Innovation Fund. The Innovation Fund is split into Discovery Grants and Operating Grants. Discovery Grants support “biomedical research by teams proposing bold and innovative research questions in women's health.” Operating Grants support areas of women’s health such as translational research in healthcare diagnostics, therapeutics, and devices and healthcare implementation research to remove barriers to access to healthcare.Calls for up to 13 Discovery Grants totalling $2 million were announced as were 15 Operating Grants totalling $9 million. A total of 24 projects were awarded at an expense to taxpayers of $13.7 million. General themes of the funded research included reproductive care and pregnancy, polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis, cancer and HPV, heart health, mental health, eating disorders, and “gender-based violence.”WAGE as a Solo ActorIn addition to partial funding of the National Women’s Health Research Initiative, WAGE also invests a significant amount of taxpayer money into other initiatives and programs aimed at improving the well-being of girls and women. A spreadsheet on the government’s website lists all the grants funded by WAGE between 2017 and 2024. As shown in the graph below, grants from WAGE amounted to $1.7 billion over this eight-year period, with annual funds ranging from about $1 million in 2017 to nearly $700 million in 2023.Text analysis of WAGE’s spreadsheet reveals that the vast majority of the approximate 2,400 funded projects were designated to either women’s or LGBTQ causes. In the spreadsheet, the words “boy” and “men” appear in project titles 20 and 42 times, respectively (and not necessarily in male-positive ways). In contrast, the words “girl” and “women” appear in project titles 75 and 599 times, respectively, and the word “feminist” appears in 67 project titles, and the phrase “LGBTQ” appears in 153 project titles.The spreadsheet also reveals three broad funding streams that the projects were aligned with. Of the projects that had funding stream information listed, 1,475 projects were associated with the “Women’s Program.” According to WAGE, the purpose of the Women’s Program is to “advance equality for women in Canada by working to address or remove systemic barriers impeding women’s progress and advancement. The [Women’s Program] supports the Government of Canada’s goal of advancing gender equality in Canada. It is consistent with Government of Canada priorities related to economic prosperity, and supports Canada’s international commitments related to gender equality.”The next most popular funding stream, which accounted for 505 projects, was “Equality for Sex, Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression Program.” According to WAGE, the purpose of this funding stream is to “advance social, political and economic equality with respect to sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression. Advancement towards a greater understanding of the intersection of sex and gender with other identity factors that include race, national and ethnic origin, Indigenous origin or identity, age, sexual orientation, socio-economic condition, place of residence and disability are encouraged under the Program."Finally, 308 projects were associated with the “Gender-Based Violence Program.” According to WAGE, the purpose of this program is to “strengthen the [gender-based violence] sector to address gaps in supports for two groups of survivors: 1) Indigenous women and their communities, and 2) underserved populations (including women living with a disability, non-status/refugee/immigrant women, LGBTQ2S, gender non-conforming people and ethno-cultural women) in Canada. The Program provides grant and contribution funding to Canadian organizations to improve supports to help create long-term, comprehensive solutions at the national, regional, and local levels.”Women RISE InitiativeAnother component of the Canadian government’s investment into women’s wellbeing is the Women RISE initiative. This initiative, which was established in March 2022, was formed out of partnerships between the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).According to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Women RISE Initiative is a “ground-breaking $24 million partnership to support research to improve the health and socioeconomic well-being of women, particularly those from marginalized communities, as part of supporting the global recovery from COVID-19.”According to the government, the Initiative was created because “[a]round the world, women and girls have disproportionately suffered from the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19. Women have borne the brunt of layoffs and loss of livelihoods, sacrificed their own health at the frontlines of the pandemic response and disproportionately shouldered the burden of the additional caregiving associated with COVID-19.”In November of 2022, the 23 recipients of the Women RISE research initiative were announced at the Canadian Conference on Global Health in Toronto. Themes of the awarded projects included infectious diseases, sexually transmitted and blood-b

On Tuesday, March 25th, the Australian Labor Party handed down the country’s federal budget for the 2025-26 financial year. Men’s health was not part of the budget. However, women’s health received its usual smorgasbord of government goodies, with Treasurer Jim Chalmers stating that women's health is a “national priority."According to government documents and Nine News, $793 million has been budgeted for women’s health. This money has been labelled “critical” and entails the following, according to Nine News:* $134.3 million for insertion and removal of long-acting reversible contraceptives by nurse practitioners* $109.1 million to fund two national trials related women’s access to contraceptives and treatment for urinary tract infections* $20.9 million to create 11 new clinics for treating endometriosis, pelvic pain, perimenopause, and menopause* $26.3 million for Medicare rebates for menopause health assessments* $277.7 million for 500 new community sector and frontline worker jobs in domestic violence* $70 million for existing services and for trialling new measures to support women and children experiencing violence* $21.4 million to improve victim and survivor engagement within the justice system* $21.8 million for First Nations women, children and communities for family, domestic and sexual violence services* $16.7 million to fund innovative approaches to address perpetrator behaviour* $606.3 million to deliver more doctors and nurses* $28 million to support the construction of the Nursing and Midwifery Academy in Victoria* $10.5 million to expand the Primary Care Nursing and Midwifery Scholarship program* $1.3 million to extend the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Education and Training Program by 12 months* $3.4 million for mentoring and coaching programs for First Nations women in business* $3.2 million to the Australian Sports Commission to help increase women and girls' participation in sports leadership through coaching, officiating and sports administrationOne might notice that these figures add up to significantly more than $793 million. This occurred, because, in an effort to show the Labor Party’s affection for its female voting bloc, Nine News revealed aspects of the federal budget that most people would consider beneficial for female wellbeing, but were not categorized by the government as “women’s health” funds. Information about these additional investments can be found in the government’s 64-page budget overview titled, “Building Australia’s Future,” and in the government’s 80-page “Women’s Budget Statement.”In the budget overview, the $793 million for women’s health is mentioned under “Strengthening Medicare” and “Better healthcare for women.” This is the part of the budget that includes funds allocated for contraceptive pills, menopause treatments, and the 11 clinics for treating endometriosis, pelvic pain, perimenopause, and menopause.Further down the budget overview, one finds a section titled “Progressing equality, supporting women.” This section describes some of the other goodies for women that were mentioned or alluded to in the Nine News report, including:* $2.6 billion for a further pay rise for aged care nurses* $3.9 billion to enhance access to legal services, including for people experiencing gender-based violence* $21.4 million to improve engagement with the justice system of victims of gender-based violence* $21.8 million to provide family, domestic and sexual violence services to First Nations women, children and communitiesHowever, for the most complete understanding of the federal budget’s allocation of funds for improving the lives of women, but not men, one needs to consult with the 80-page Women’s Budget Statement.This Statement is divided into five themes:* Gender-based violence* Unpaid and paid care* Economic equality and security* Health (i.e., the “women’s health” section)* Leadership, representation and decisionEach major theme is made of various subthemes that serve as targets of the new budget. These subthemes include but are not limited to:* Ending gender-based violence* Ensuring safe education and workplaces for women* Providing cost-of-living relief to women and families* Increasing women’s workforce participation* Narrowing the gender pay gap* Enhancing long-term economic equality and security for women* Women in leadership and decision-making* Women’s and girl’s representation and participation in sport* Building gender equality capability across government* Global leadership on gender equalityMany of the details of these subthemes were not described in the Nine News report or the budget overview, and they reveal the extent to which the budget has been underpinned by feminist ideology and a bias against men.On page 11, under the theme of “gender-based violence,” one learns that some portion of $534.5 million will go toward “break[ing] the cycle of violence and prevent[ing] further harm by developing national standards for men’s behaviour change…” [italics added]Neither the budget nor the Women’s Budget Statement mentioned funds for developing national standards for women’s behaviour change.On page 18, one learns of $925.2 million for the “Leaving Violence Program,” and on page 24 one learns of the development of the National Student Ombudsman whose function will be to allow university students to “escalate complaints about the actions of their higher education provider, including complaints about sexual harassment, assault and violence.” Regarding the Leaving Violence Program, the Women’s Budget Statement states that its purpose is to “empower people to leave violent relationships through financial support packages.” The program will provide financial support packages of up to $5,000 and be open to migrants regardless of visa status. The program is expected to support approximately 36,000 people each year.Neither the budget nor the Women’s Budget Statement mentioned the possibility that the Leaving Violence Program might incentive false allegations of intimate partner violence (likely against men). The extent to which the National Student Ombudsman might also increase false allegations, specifically of sexual violence among university students, is something else to keep an eye on in the coming months.On page 37, one learns of the budget goal of “building a stronger workforce pipeline” for unpaid and paid care work. Here, the Labor government seeks to pour money into the care sector to make care work “more attractive by supporting fair numeration.” They also state that they want to increase men’s participation in the care sector by “break[ing] down stereotypes that care is ‘women’s work.’”Yet, the Labor government reinforces this stereotype when it admits that the reason that it will provide the Commonwealth Prac Payment of $331 per week for education, social work, nursing, and midwifery students while they undertake their practicums is because most of those students are women. The Women’s Budget Statement states: “Many of these students will likely be women. In 2022, women made up 81 per cent of enrolments in teaching, nursing, midwifery, and social work higher education courses, and 84 per cent of 2022 commencements in the Diploma of Nursing.” The Statement continues: “Given women represent almost 90 per cent of the nursing and midwifery sector professions, women stand to benefit the most from this measure.”Thus, by examining the Women’s Budget Statement, one see that reports of $793 million for women’s health are somewhat misleading. Many of the items in the Women’s Budget Statement that were not designated as “women’s health” will undoubtedly still improve the quality of life for many women. Where to the draw the line on what is “health” funding versus other funding is a matter of debate, but that such a debate is possible is something to be aware of when reading government reports, press releases, and data tables, even from men’s health groups or researchers. For example, in my previous examinations of sex differences in funding, I have explored only the narrow topic of investment into men’s and women’s health research (see graph below).Similarly, in their response to the federal budget, the Australian Men’s Health Forum published a table (shown below) that lists annual budgeting for men’s and women’s health since 2022-23. The table clearly shows a consistent bias in investing millions more dollars into women’s than men’s health. Over the four-year period, the Australian government invested $1.3 billion into women’s health and $22.5 million into men’s health. Yet, in the table, the value listed for women’s health in 2025-26 is $793 million. Thus, as lopsided as the numbers in the table are, they do not reflect the full extent of bias in funding, as they do not account for all the other women’s programs that have been funded over the years and are more indirectly linked to health.Interestingly, had the Labor government wanted to talk about token funding for male wellbeing, they could have. For example, the budget includes $47.6 million for the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, with suggestions that the money be used for veteran suicide prevention and veteran compensation and rehabilitation claims. Men make up 79.4% of current members of the Australian Defence Forces and 86.6% of individuals who have previously served in the Australian Defence Forces. Thus, men stand to benefit the most from this budget item.The budget also includes $9.3 billion for homelessness. Men make up a 56% of the homeless population in Australia. Thus, many men also stand to benefit from this budget item.Why the Labor government chose not to frame such budget items in a male-supportive way is unclear. Doing so would have required explicit acknowledgment of male suffering and disadvantage, and this would be at odds with many other aspects of their feminist-influenced budget. That the budget was influenced by feminist ideology is evident from the following observations:* First, the budget

(*Don’t forget to scroll to the end to see more interesting photographs!)Today, there exists much concern about women’s representation as participants in exercise research. I have covered this topic in essays such as “History Didn’t Start at Title IX,” “Men: The Martyrs of Medicine,” and “Is There a Bias Against Women in Research?”To the extent that women have been less frequent participants in certain types of research published in specific journals in certain years, this does not then necessitate a conclusion of discrimination against potential female participants. For one, participation in research is not always desired. Some research is boring, confronting, discomforting, invasive, or carries health risks. In fact, our survey revealed that men are generally less worried about such things when contemplating whether to participate in a study.Discussions about these aspects of research – the tests and interventions administered and how they are viewed by potential participants – are often lacking from papers that espouse gender bias or discrimination as the sole or primary cause of female participant “underrepresentation.” Yet, discussions about the nuisances of research procedures and processes are critical for understanding men’s participation in certain types of research and what their participation has meant for society, including for women. Counterfactuals, or mental simulations, can be useful for facilitating such an understanding.Consider what would be said today if the historical record were to show that women were 70% of participants in early medical research. Early medical research would have been the riskiest and the most likely to not involve ethics board approval or informed consent. Thus, one can reasonably predict that contemporary gynocentrists would not express glee at this 70% representation, though they should based on their current real-world frustrations about the supposed historical exclusion of women from research. Instead, they would reframe this counterfactual 70% female representation in a way that maintains female disadvantage or victimization. They would state that early researchers, under patriarchal influence, were using women’s bodies for experimentation. In academic papers and books, they would detail this traumatic history and say that these women were brave, heroic, and the martyrs of science.This mental simulation is intended to highlight an issue with the female underrepresentation narrative and to provoke thought about why we do not extend such considerations to the men who were often participants in the earliest and riskiest research. In part, this lack of consideration might stem from a lack of information available on the history of experimentation, particularly within the fields of exercise science, physical education, physical therapy, and applied physiology.I recently filled one of these information gaps with a paper published in the Journal of Men’s Health titled “Bibliometric guide to photographs of male participants in early exercise and physical medicine research.”The purpose of my research was to create a bibliometric list of papers that include photographs of boys and men participating in early exercise science, physical education, physical therapy, and applied physiology research. The list can then serve as a quick reference for educators and researchers who are trying to find photographs to be used in course lectures, university textbooks, and academic papers on the history of research participation. By showing audiences such photographs, educators and researchers can humanize men, showing their contributions to society via participation in early experimental research.MethodsFor the analysis, I searched the entire archives of three of the most historically relevant journals: Research Quarterly (1930-1979), Journal of Applied Physiology (1948-1979), and Medicine and Science in Sports (1969-1979). For these journals, I downloaded their digital archives and opened each individual paper to identify photographs of research participants. I also searched my own personal digital library of articles associated with my previous historical research. My analysis ended in the year 1979, in part, to coincide with my other historical research.ResultsI found a total of 304 papers published before 1980 that included photographs of boys and men participating in early studies on exercise and related topics. Forty-four percent of the papers were published in Research Quarterly. The papers included a total of 733 photographs of 46 boys and 475 men. The earliest paper was authored by Henry Beyer in 1894, and photographs from that paper are shown below.In my paper, I list all 304 papers in tables. The tables include descriptions of the experimental procedures depicted in the photographs and links to where the papers are located online. Often, photographs depicted boys and men performing tests of muscle strength, muscle endurance, and motor learning skills. Men were also frequently photographed having their oxygen consumption measured at rest, during physical exercise, and during exposure to altered environmental conditions. Another common type of photograph was that of male body build and posture. Sometimes, these men were photographed naked.Many of the procedures that men were shown performing or undergoing are similar to those that women of that era also performed or underwent, including being photographed naked. However, there also appear to be sex differences in the types of procedures completed during this era of science. Examples of such procedures can be found at the end of this post, where I show some of the most intriguing and informative photographs from my research. In my paper, I briefly explain the sex difference:“Photographs in the current bibliometric list illustrate what men’s historical participation in exercise physiology has entailed. These photographs show men participating in a range of physiological and medical procedures. It is difficult to imagine women being more likely than men to volunteer to undergo many of these procedures. Some examples include exposure to high gravitational forces or other environmental conditions that cause “blackouts” or increase the risk of losing consciousness [23, 37, 53, 324]; exposure to gasses that cause itchiness and damage to the skin of the face [87]; sitting on an apparatus designed to induce motion sickness [16]; and standing on one’s head while cardiorespiratory outcomes are measured [31, 35, 65]. In another study, men who were deaf or who had trouble hearing were dumped into a swimming pool to try to better understand human proprioception [172]. Finally, two papers on the bibliometric list include photographs of men sitting on moving cars, while holding gas collection bags, which are attached to a man who is running next to the moving car [79, 94].”ConclusionHistorical naivety and ideological bias are clouding interpretations of the history of male and female participation in exercise and physical medicine research. My recent paper in the Journal of Men’s Health is intended to help educators, researchers, and students see through these clouds. The discovered photographs show boys and men partaking in a range of experimental procedures, thus providing a basis for educating students about the nature of the type of research that men frequently participated in.Women also served as participants in much early research. Nevertheless, men completed many experimental procedures that are difficult to envision many women and many other men completing. Thus, the men who did participate in these experiments assumed much of the initial risk of early biological research. Men were often the first exposed to deadly agents, high gravitational forces, or resistance exercise with eccentric overload.Gynocentrists who write about women’s “historical exclusion” and “underrepresentation” as research participants conveniently ignore such historical nuance. They also fail to recognize that although men might have made up more than 50% of participants in specific types of research in certain years, this does not mean that women’s health and performance were completely ignored. Women were participants in much early research, and claims of their historical widespread exclusion have been debunked multiple times. Moreover, the current narrative of female participant “underrepresentation” is further flawed because it does not acknowledge that sex differences exist in interest and willingness to participate in research. Finally, as illustrated in the counterfactual presented earlier, even if women had been more than 50% of early research participants, contemporary gynocentrists would interpret that as representing female discrimination – in the form of the patriarchy’s use and abuse of the female body. There is simply never any winning against subjective feminist epistemology, which always try to squirm and wiggle its way around objective reality to maintain female victimization.My hope is that the promoters of the “historical exclusion” and “underrepresentation” narratives take a moment to come off their public soapboxes, which they were likely elevated to by some gender equity initiative, and print off a copy of my recent paper and read it. Then, assuming they have learned something from the paper, they ought to consider taking a figurative knee at the altar of masculinity, and say to the brothers of the barbell and the blackout: “Thank you.”“Buckle Up, Boys!” Measuring Oxygen Consumption Running OutdoorsSource: Daniels J. Portable respiratory gas collection equipment. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1971; 31: 164–167.Source: Daniels J, Oldridge N. The effects of alternate exposure to altitude and sea level on world-class middle-distance runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1970; 2: 107–112.Blackouts and Exposure to High Gravitational ForcesSource: Duane TD, Lewis DH. Electroretinogram in man during blackout. Journal of Applied Physiolog