Discover The Turbulent World with James M. Dorsey

The Turbulent World with James M. Dorsey

The Turbulent World with James M. Dorsey

Author: James M. Dorsey

Subscribed: 49Played: 2,962Subscribe

Share

© All rights reserved

Description

Dr. James M. Dorsey is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, co-director of the University of Würzburg’s Institute for Fan Culture, and co-host of the New Books in Middle Eastern Studies podcast. James is the author of The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer blog, a book with the same title as well as Comparative Political Transitions between Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa, co-authored with Dr. Teresita Cruz-Del Rosario and Shifting Sands, Essays on Sports and Politics in the Middle East and North Africa.

918 Episodes

Reverse

Divide and conquer has become Israel’s main operating principle in a world in which it stands condemned for its war conduct, impunity, and intransigence, and is increasingly isolated.

Israel applies the principle whether it is in Gaza, Syria, its uphill battle to gain the high ground in its information wars, or its efforts to encourage Jewish immigration.

In Israel’s latest application of the principle, it sees an opportunity to capitalise on Christian assertions that their African brethren are the primary victims of Muslim aggression in what amounts to a religion-driven conflict.

A recent spate of kidnappings for ransom by criminal gangs and jihadists in Nigeria, a country with swaths of ungoverned land, and long-standing violence driven as much by religion and ethnicity as by access to land and water and crime, has fuelled the assertions.

When Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman visited Washington this week, he shifted multiple paradigms.

In an increasingly multilateral world, Mr. Bin Salman, backed by US President Donald Trump, suggested that the kingdom is claiming its place at the table as a geopolitical and geoeconomic powerhouse.

US support gives (Mr. Bin Salman) more room to negotiate with big powers—US, China, and even Israel—on his own terms,” said analyst Hesham Alghannam.

Seen through a geopolitical lens, Mr. Bin Salman’s commercial dealings are about more than diversifying the kingdom’s oil-dependent economy and turning it into a 21st-century, cutting-edge knowledge society.

In Mr. Bin Salman's mind, the dealings are about putting Saudi Arabia on near-par with the United States, China, and India in a world that is multilateral rather than bipolar, with the US and China as the dominant powers, or tripolar, with India eventually added into the mix.

James discusses this week’s latest Middle East developments on Radio Islam.

Israel’s US support base is narrowing.

Coming at Israel from different directions, US President Donald Trump, increasingly critical Evangelicals, until recently a rock-solid Israeli support base, and influential Make America Great Again torchbearers are chipping away at Israel’s standing.

On this edition of Parallax Views, independent journalist James M. Dorsey of The Turbulent World with James M. Dorsey returns for our regular Middle East update. In this wide-ranging conversation, we discuss the historic visit of Al-Sharaa to Washington and what it signals for U.S.–Syria relations, the internal ethno-religious divides within Syria, and the concerns of the Alawite and other minorities amid shifting regional dynamics.

Alarmed by shifting attitudes towards Israel and rising anti-Semitism in Trump’s support base, Israeli officials likely see Ye’s repentance as a rare success of their multi-million dollar endeavour to halt a tidal shift among American Evangelicals and Make America Great Again (MAGA) figures away from Israel and towards the Palestinians that, at times, is laced with anti-Semitism.

James discusses this week’s Middle East developments on Radio Islam.

Evangelicals to the rescue. That may seem an oxymoron in the case of Gaza and Palestine.

Yet, the ground is shifting under a core, traditionally pro-Israel pillar of US President Donald Trump’s support base.

The shift is occurring against the backdrop of legitimate concern that mounting criticism of Israel in the Make America Great Again (MAGA) crowd is, at times, laced with anti-Semitism and the rise of New York mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, a proponent of a one-state instead of a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Mr. Mamdani’s candidacy and electoral victory have provoked a wave of Islamophobia, rather than the frank and healthy debate needed amid growing doubts whether a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains feasible.

Ironically, mounting Evangelical empathy with the plight of the Palestinians constitutes, among Western Evangelicals, a break with their politicised anti-Semitic End Times theology that long formed the basis for the Christians’ uncritical alliance with Israel.

James discusses this week’s developments on Radio Islam’s Middle East Report.

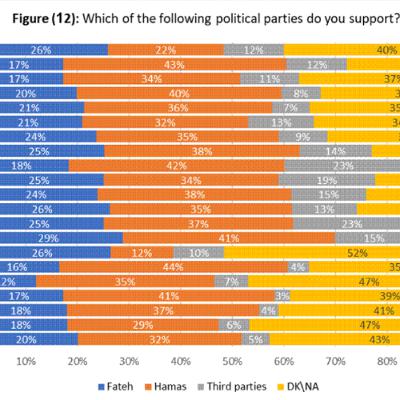

Palestinian public opinion is blowing new wind into Hamas’s sails, shredded by two years of brutal warfare in Gaza.

The most recent public opinion poll, conducted in late October after a fragile ceasefire took hold, suggests that Hamas may have reversed its consistent rock bottom performance in repeated surveys during the war.

James discusses this week's Middle East events on Radio Islam

US President Donald Trump may think his 20-point proposal will end the Gaza war and solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but reality on the ground suggests otherwise.

To be sure, Mr. Trump's proposal is the only game in town, if only because no one, not Israel, not the Palestinians, who weren't consulted, not the Arab states, wants to get on the wrong side of the president.

While all welcomed Mr. Trump's proposal, a set of principles with no terms or mechanism for implementation, no one has wholeheartedly bought into the scheme.

Nowhere are the lines separating legitimate criticism of Israel and anti-Semitism more blurred than on the soccer pitch.

A series of incidents in the last year highlights the confusion and obfuscation, part the product of an Israeli effort to deliberately conflate criticism with anti-Semitism in a bid to stifle questioning of Israeli policies and part the result of a decades-long information war that pits Israelis and Jews against Palestinians, Arabs and Muslims in which labelling of the other is often ideologically determined.

The labelling includes Israel's consistent referral to Israeli Palestinians as Arabs rather than Israeli Palestinians in a bid to erase a separate Palestinian identity, and many Palestinians, Arabs, and Muslims using the terms Israeli, Zionist, and Jewish interchangeably rather than acknowledging the differences between the various categories.

Adding to the confusion and obfuscation is the fact that, colloquially, many Palestinians, Arabs, and Muslims often indiscriminately refer to Israelis, Jews, and Zionists as ‘yahud,’ or Jews.

James discusses the prospects of US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal on Radio Islam.

It took barely 24 hours for US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal to fray at the edges, with Israel and Hamas hurling allegations of ceasefire violations at one another.

Israel has approved a ceasefire deal with Hamas. But with one explosion reported in Gaza hours after the deal was passed, can we still expect peace as Israel begins withdrawing from parts of Gaza? Lance Alexander and Daniel Martin speak with correspondent Blake Sifton and James M. Dorsey, Adjunct Senior Fellow, RSIS.

James M. Dorsey from the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies weighs in on the Israel-Hamas Gaza ceasefire deal and discusses whether Israel will commit to the agreement.

Staring at minute 04:18, James discusses the Gaza ceasefire talks on CNA

James M. Dorsey discusses on TRT World what happens next as Hamas and Israel negotiate the implementation of US President Donald Trump’s 20-point plan to end the Gaza war.

During this week’s Middle East Report, analyst James M. Dorsey provided insights into the evolving geopolitical landscape of the region.