Discover Turan Tales

Turan Tales

Turan Tales

Author: Agnieszka Pikulicka

Subscribed: 12Played: 89Subscribe

Share

© Turan Tales

Description

Turan Tales is a weekly podcast covering underreported stories of people, politics and social change in Central Asia by journalist and author Agnieszka Pikulicka

turantales.substack.com

turantales.substack.com

26 Episodes

Reverse

This week on TURAN TALK we trace the history of US relations with Central Asia through the experiences of Daniel Rosenblum - a former US ambassador to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and a long-time expert on the region. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week, we’re looking into a fascinating and often misunderstood topic: witchcraft, clairvoyance, fortune telling, and other spiritual practices popular in Tajikistan and the rest of Central Asia.Joining us is Dr Anna Cieślewska, a social anthropologist and orientalist at the Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Łódź in Poland. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week, we’re talking about uyat and Central Asia’s culture of shame. Joining us is Dr. Hélène Thibault, Associate Professor of Political Science at Nazarbayev University in Astana. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Astana has risen from the steppe as a city of glass, steel, and soaring ambition - a capital built to embody a nation’s dreams. But can a dream live up to its promise?Support Turan Tales with a paid subscription at: turantales.substack.com/subscribe Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

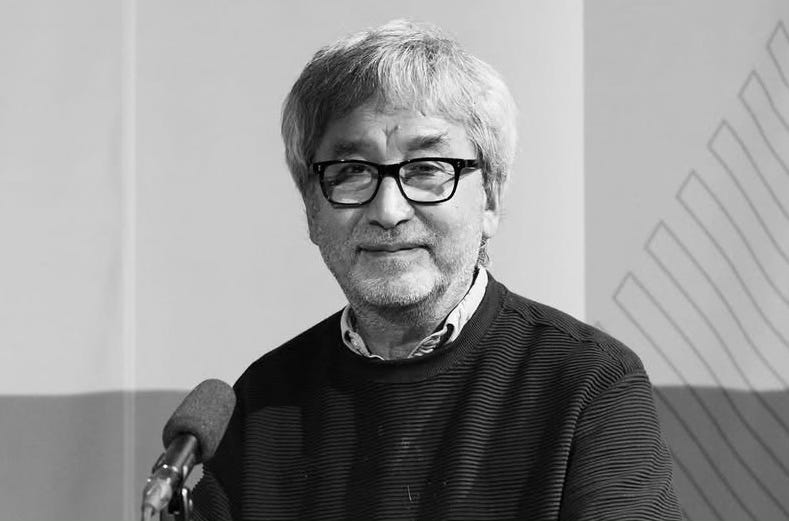

This week, we’re talking to Uzbekistan’s most prominent writer, Hamid Ismailov. He is a longtime BBC and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty journalist, and the author of numerous works of fiction and poetry in several languages. He is the recipient of the EBRD Literature Prize for his novel The Devils’ Dance – sometimes called “an Uzbek Game of Thrones.” His latest novel, We Computers, has been the finalist of the 2025 National Book Award for Translated Literature, one of the most prestigious literary prizes in the U.S. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Our guest this week is one of the most fascinating contemporary scholars from Kazakhstan and the author of What Does It Mean to Be Kazakhstani - Diana Kudaibergen, a cultural and political sociologist and Lecturer in Central Asian Politics and Society at University College London. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

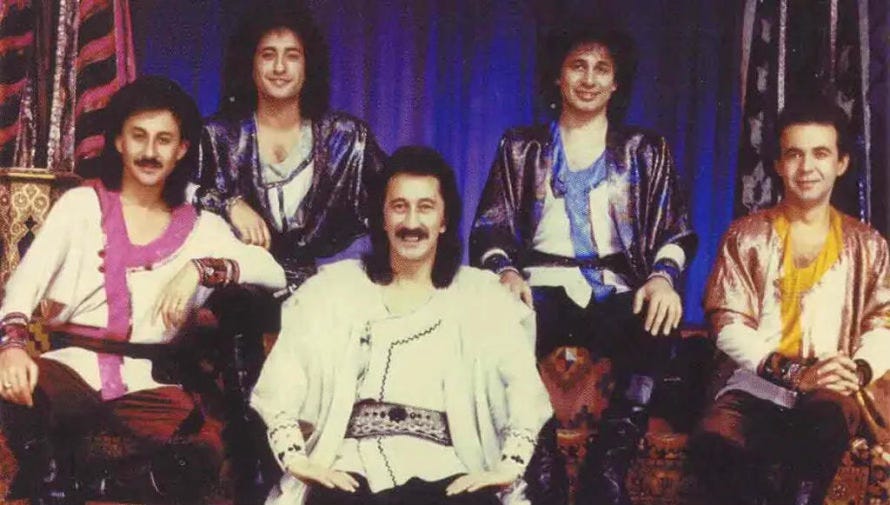

Hi all,Our guest today once shared with me a fascinating story. Back in 1981, when the Uzbek pop group Yalla was touring Uzbekistan, they passed through the town of Uchkuduk — a name worthy of a song. Yurii Entin, one of the band’s lyricists, supposedly wrote it in just 40 minutes. Little did he know that his quick scribbles would go on to make history in Uzbek and Soviet pop music.Uchkuduk, a song about a small town in Uzbekistan, became so popular that the authorities banned it from the airwaves for an entire year, fearing it would draw attention to the area’s main industry: uranium mining. According to legend, the song made the band so recognizable that when its frontman, Farrukh Zakirov, once came to the Kremlin Palace for a concert, a security guard simply said: “Oh, Uchkuduk — come right through.”If you haven’t yet, I’d love for you to become a paying subscriber — it makes a huge differenceThis episode is a special one: we’ll talk about Central Asian music in Soviet times, and about the history of the region as told through music. Joining us is Leora Eisenberg, a fifth-year PhD student at Harvard University, where she studies Soviet and Central Asian history, with a special focus on Soviet estrada, in other words, the pop music, of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.Leora has kindly shared with us one of her favorite playlists of Soviet Central Asian estrada. You can find it here: My fellow Poles will even find a little surprise there: one of the songs is a Kazakh remake of Szła dzieweczka do laseczka, a folk tune that needs no introduction.Hope you will enjoy this one!Have a great end of the week,— Agnieszka Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Hi all,I’m writing and recording this week’s intro from my new home in Almaty. The weather is perfect, as it so often is in late summer. I spend my days getting to know my neighborhood, walking my dog, meeting friends old and new, and writing. I’m very grateful to be back in Central Asia after almost four years in Europe. I hope Almaty will be a good host for me — and for Turan Tales. If any of you, dear listeners, are around, make sure to drop me a line.This week’s guest and I will be discussing a topic that always draws a lot of attention: first daughters and the female face of Central Asian politics. Since the five Central Asian republics gained independence, there has been no shortage of presidential daughters. Some have been famous, audacious, and highly ambitious, like the legendary Gulnara Karimova and Dariga Nazarbayeva. Others have been more low-profile but still played important roles in their fathers’ administrations, such as the Mirziyoyev sisters or some of the many daughters of Tajikistan’s president, Emomali Rahmon. And some are only now stepping out of the shadows, like Oguljahan Atabayeva from Turkmenistan.Regardless of their public profile, all of them play a role in preserving their fathers’ rule. The questions are: Could any of them succeed their father? Could a woman ever become president in Central Asia? And what role, if any, do first daughters play in changing the position of women in their respective countries?Joining us is Galiya Ibragimova, an Uzbekistan-born freelance journalist and researcher focusing on political transformation in Central Asia and Eastern Europe. She is also a PhD candidate in political science at the University of World Economy and Diplomacy in Tashkent.I hope you enjoy this one!Have a great end of the week,— Agnieszka Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

The Caspian Sea is shrinking, its shores littered with seal carcasses. For scientist Assel Baimukanova, each one tells the story of an ecosystem on the brink. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week, we’re taking a deeper look at Central Asia’s postcolonial legacy and how Russia’s centuries-long influence has shaped ways of thinking, institutions, and everyday life in the region.Russian colonisation of Central Asia began in the early 1800s and expanded steadily throughout the 19th century. Following the Russian Revolution, most of Central Asia was incorporated into the Soviet Union. This period brought rapid industrialisation and infrastructure development – but it also suppressed local cultures in a manner typical of colonial regimes.The Russian language came to be seen as a marker of civilisation and positioned as superior to local languages, while people were expected to conform to the values of a secular, rational Soviet state.To meet the demands of the increasingly authoritarian new super-state, millions of people, representatives of ethnic groups seen as suspicious and potentially rebellious, were deported to Central Asia.GULAGs, that is - forced labour camps - were established across the Soviet periphery. Finally, man-made famines – driven by brutal collectivisation policies – claimed thousands of lives in both Central Asia and Ukraine. The ethnic and demographic makeup of the region was permanently altered.And yet, some scholars – both in Russia and the West – continue to argue that the Soviet Union was not an empire, but rather a benevolent force striving to build a just, multicultural society.Even in modern-day Central Asian states, which gained independence after the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, many still express nostalgia for the Soviet past, often overlooking its darker chapters. Russian remains widely spoken – and for many, it is still the only language they know.Today, we will look at all those paradoxes, explore Soviet nostalgia and imperial melancholia, focusing on a rarely heard perspective: that of Turkmenistan.Joining us is Selbi Durdiyeva, a decolonial scholar originally from Turkmenistan, and a Teaching Fellow at the College of Law, Anthropology and Politics, at SOAS, University of London. Her research interests include decoloniality, transitional justice, and socio-legal approaches. Her book titled “The Role of Civil Society in Transitional Justice: The Case of Russia” was published by Routledge in 2024. She is also my Substack colleague and runs a newsletter called “Nodes from Pluriverse.” Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week we are revisiting the legacy of one of the most important figures who shaped Central Asia following the collapse of the Soviet Union: Nursultan Nazarbayev, the former president of Kazakhstan.Born in 1940, Nazarbayev served as Kazakhstan’s first president from 1991 until 2019, when he stepped down and transferred power to Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, then Chairman of the Senate – and the current president.Like all Central Asian leaders, Nazarbayev left behind a mixed legacy. While he sought to be remembered as the Leader of the Nation – Elbasy – and the founding father of modern Kazakhstan, many continue to associate him with autocratic rule and widespread corruption.In 2022, following mass protests – known as Qantar, or Bloody January – in which more than 200 people likely lost their lives, Nazarbayev was stripped of his Elbasy title and his position as chairman of the Security Council, a role that was originally intended to be held for life.To discuss Nursultan Nazarbayev, his presidency, and his legacy, we are joined by Joanna Lillis, a Kazakhstan-based journalist with two decades of experience reporting from Central Asia. She is the author of Dark shadows: Inside the secret world of Kazakhstan and the upcoming Silk mirage: Through the looking glass in Uzbekistan, set to be published this autumn. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

According to the Russian Interior Ministry, there are about 10.5 million people from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan working in the country. It has long been clear that they experience derogatory treatment, humiliation, and racism on a daily basis.The situation has further deteriorated since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In September of that year, the Duma – Russia’s lower chamber of parliament – passed a law fast-tracking citizenship in exchange for military service. Around the same time, Moscow’s Mayor Sergey Sobyanin launched an army enlistment campaign aimed at migrants.According to a report by Hochu Zhit , a project by Ukraine’s Defence Ministry, more than three thousand Central Asians are now serving in Russia’s military.The numbers recorded in the Hochu Zhit report are the following:· 1,110 Uzbek nationals have been enlisted, of whom 109 have been killed.· 931 Tajiks enlisted, 196 killed.· 360 Kyrgyz citizens enlisted, 38 killed.· 170 Turkmen enlisted, 27 killed.· 661 Kazakhs enlisted, 78 killed.These numbers have likely changed since May, when the report was published.Our conversation today focuses on a documentary directed by my dear friend and one of the journalists whose work and courage I truly admire: Shahida Tulaganova. Her new film titled Spirit Untamed tells the story Bahrom Hamroev, a well-known human rights defender from Uzbekistan who spent years working with and supporting Central Asian migrant workers in Russia.Hamroev was arrested at the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on suspicion of being part of Hizb ut-Tahrir, a non-violent Islamist organisation banned in Russia – a charge he denies. He was sentenced to 13 years and nine months for allegedly justifying terrorism and organising the activities of a terrorist organisation.You can watch the film’s trailer here.Shahida Tulaganova is an Emmy-nominated filmmaker, born and raised in Uzbekistan and currently based in London. Shahida began her journalism career with BBC News in 1996. Since then, she has reported from Syria, Afghanistan, Eastern Ukraine, Palestine, and Somalia, among other places. Her two recent films - Children of Ukraine (2022) and Ukraine’s Stolen Children (2023) - focused on the situation of children during Russia’s war against Ukraine and were produced by ITV. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

A boy on the screen, 12-year-old Yersultan, cries in a rare emotional outburst against his father. “What am I, just cattle you can give away?” he asks, tears streaming down his chubby cheeks.His father is confused. Moments earlier, he was furious, angered by his son’s poor school performance and lack of the skills needed to survive the harsh rural life. But Yersultan’s outburst softens his tough posture, and though he reaches out to hug the boy, he meets resistance.Is it too late to apologise and be a family again?The answer never comes.This scene is part of Bauryna Salu, a Kazakh Oscar nominee and the directorial debut of Askhat Kuchinchirekov. The film has won several awards, including the Special Prize at the Cinema Heritage Festival in France, the Best Youth Feature Film Award at the Asia Pacific Screen Awards, and the Best Feature Film Prize at the Ischia Film Festival in Italy. Kuchinchirekov was also nominated for the New Directors Award at the prestigious San Sebastian International Film Festival.This scene was more than fiction – it reflected a moment Kuchinchirekov had replayed in his own mind countless times. Unlike his protagonist, Yersultan, however, he never found the courage to confront his father before he passed away.“I could not confront my father. And I could never call my biological parents ‘dad’ and ‘mom,’ or hug them. There is a feeling inside you that doesn't let you say it,” Kuchinchirekov says, sitting in a small café on the outskirts of Almaty.“It would feel like betraying my grandmother.”Like Yersultan, Kuchinchirekov was given away by his parents as a child to be raised by his grandmother, who lived in a village several hundred kilometres away. This was not an act of cruelty or neglect – it was part of an old nomadic tradition practiced in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Karakalpakstan for hundreds of years. The custom is called bauryna salu, or sometimes nebere aluu. According to tradition, a man gives his first child to his own parents to be raised.In another version, called bala beru, a couple gifts their first child to childless relatives or even strangers, as childlessness was considered a lonely and tragic fate in traditional nomadic societies. Those without children were referred to as kubas, or “lonely heads.” The emotional realities of the children, mothers, and grandparents involved in these practices were seldom discussed – that is, until now. Kuchinchirekov’s film, which has toured festivals and cinemas across Europe this year, seeks to give voice to their experiences.In nomadic communities, where large families lived in multigenerational households, bauryna salu had practical roots. Young adults were occupied with tending cattle, farming, or building yurts, while elders, with more time, cared for the children. New mothers often struggled to balance household duties with raising children, so grandparents stepped in.In theory, another purpose for the tradition was to reduce infant mortality. Young women in nomadic societies often gave birth early and frequently, lacking the experience to care for newborns. As a result, many babies died. Entrusting a child to older, more experienced hands increased their chance of survival.Over time, the practice gained symbolic meaning, with children viewed as the source of a family’s strength and happiness. Entrusting a firstborn to one’s parents became a profound expression of love and respect.This gift also elevated the parents’ status. For a grandmother, who has spent her life in submission to her husband or in-laws, raising a grandchild was a reward and recognition. It allowed her to apply the wisdom she had gathered over her lifetime to raise a child slowly and patiently, unlike her own children, whom she raised as a young, inexperienced woman.It is also believed that children raised by elders grow wiser and more mature. Living among elders provides deeper exposure to the community’s traditions, stories, and values – knowledge their siblings may not receive.In modern times, the practice often serves a different purpose: filling the empty nests of aging parents. Grandparents want company, and a grandchild is a source of purpose and support. Some grandmothers even negotiate the adoption – either formally or informally – of the firstborn before the child is born. In some families, the grandparents take over after breastfeeding ends. In others, young mothers are not even allowed to touch the child.In many cases, the firstborn son of a son is considered as the property of the grandparents. Sometimes they demand the child, regardless of the mother’s wishes. Resisting their authority is viewed as shameful and disrespectful in deeply hierarchical societies where elders must be obeyed.Children given away in this manner – especially boys – are raised as the youngest members of their new household and are expected to remain with their grandparents for life, supporting them until their death.In other cases, young mothers, overwhelmed by early motherhood or subsequent pregnancies, give their children to the grandparents as a form of relief. Some mothers live or work abroad, and leaving the child behind is seen as a practical, even necessary, solution.This was Askhat Kuchinchirekov’s story – and likely Yersultan’s as well.The film’s protagonist lives with his elderly grandmother and leads a relatively carefree life. He supports her with household duties and clearly loves her. Despite this attachment, he cannot stop thinking about his biological parents – the people who left him shortly after birth and never sought to build a bond with him. He holds their photograph, searching for resemblance. Did he inherit his mother’s nose or his father’s eyes? Could they ever be a family?When his grandmother dies, Yersultan travels to his parents’ village, only to face rural hardship, social exclusion, and his parents’ cold indifference.The film delves deeply into the emotions of a child who feels rejected at birth – and his struggle to understand why.Born in 1982 during the final decade of the Soviet Union, Kuchinchirekov, the director of Bauryna Salu, was given to his grandmother to raise after his mother got pregnant with his younger sister. Raising two children under harsh economic conditions in southern Russia, close to the Kazakh border, was more than she could manage, even with her husband’s support.Kuchinchirekov was one year and three months old when the family brought him to northern Kazakhstan and left him at his grandparents’ humble home. He soon forgot the smell of his mother’s skin and the warmth of her body.“For a child, everything relates to smell. If you don’t have common smells with someone, you don’t have much in common,” he tells me.He grew up surrounded by his grandmother’s boundless love. She taught him everything and made him who he is today. But even her devotion could not fill the void left by a mother’s absence.“I felt the same thing many others like me feel. You grow up with this sense that you’re not really needed. And that feeling stays with you for life,” he says.“Some people cope, others become aggressive, and some suppress it. For me, it fuelled creativity, expressed through film.”Kuchinchirekov knew his parents, but he never bonded with them. They didn’t see his first steps or help him with his homework. Compared to his grandparents, who cared for him when he was sick and cheered his first words, they were strangers.“I don’t believe what they say – that a psychologist can fix it. That feeling of abandonment never goes away. You’ve never lived with these people; you don’t share any experiences. That barrier remains. They weren’t there when you scraped your knee or fell in love for the first time,” he says.Although he adored his grandmother, their relationship wasn’t the same as mother and child. She was gentle – even when she scolded him. There were no strict boundaries or rules.“I had very few restrictions and enjoyed great freedom. And that freedom profoundly shaped me,” Kuchinchirekov says.As a teenager, he began to notice how his life differed from his classmates. He wasn’t discriminated against, yet he felt different. He envied his peers who had a “normal” family – namely, a mother and father. Resentment grew within him.The first time I witnessed bauryna salu in real life, no one could name it for me. It was in 2015, during my first visit to Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan. Through Couchsurfing, an app connecting travellers with local hosts, I met Timur, a Karakalpak man around my age, eager to host tourists for free.Timur lived in Nukus with his wife, son and beloved parents, who had an apartment just across the hall on the same floor. While my companion and I stayed with Timur and his wife, their son slept with his grandparents. Initially, I assumed this was a temporary arrangement, but Timur soon explained the family’s rules.As the youngest son, he was traditionally obligated to remain close to his parents. However, working abroad in Russia, Timur was rarely home. To bridge this gap, he entrusted his first son to his parents – a sign of love, respect, and appreciation for all they had done, meant to compensate for his absence.Timur’s son called him “brother,” reserving “mom” and “dad” for his grandparents. He spent most of his time with them – riding in the car with his grandfather, shopping at the market, and visiting relatives.Timur insisted this was a mark of respect, but I couldn’t help noticing how hard his wife restrained herself from touching her firstborn, calling him her child, or hugging him too tightly.Unlike her husband, she hadn’t grown up with this tradition. She came from Andijan in the Ferghana Valley, on the other side of Uzbekistan, about 1,380 km from Nukus – a 20-hour drive, according to Google Maps.They met by chance in the 2010s when Timur’s friend randomly called phone numbers, hoping to connect with young women open to chatting. This was a not-uncommon practice in Uzbekistan’s conservative communities, wh

This week, we’re exploring the issue of energy deficiency in the region and how best to address it. Joining us is Anatole Boute, Professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. I asked him whether nuclear power is the right path for Central Asia, what needs to be done to improve access to cheap and clean energy, and whether Central Asian states are ready to cooperate in this vital sector. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week we’re looking at an important regional story: cotton, or “oq oltin”(“white gold”), as Uzbeks call it. From forced labour in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to the shrinking of the Aral Sea, we explore what’s changed, what hasn’t, and whether the region’s cotton is finally becoming ethical.Joining us is Umida Niyazova, head and founder of the Uzbek Forum for Human Rights, who has been monitoring labour conditions in Uzbekistan’s cotton fields for many years. I asked her about her personal journey and why she founded her organisation in Germany, what cotton means to local communities in Central Asia, and the main labour and human rights challenges still facing the industry in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan today. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

In this week’s episode, joining us is a person who knows the Kyrgyz system inside out: Rinat Tuhvatshin, the co-founder and current Chief Technology Officer of Kloop -- Kyrgyzstan's leading investigative media outlet. I have asked him about the recent arrests of Kloop’s collaborators, the founding of Kloop and how the situation in Kyrgyzstan has been changing over the years. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Meerim still remembers the price her husband paid for luring her to his village. It was 1964 and her freedom was worth 80 roubles – equivalent to a plane ticket from Moscow to Bratsk, a “Sputnik” bicycle, a pair of winter shoes or coat in a Bishkek store, or, with luck, a pair of black-market jeans. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week, we’ll be looking at the recent complaint filed against Tajikistan with the International Criminal Court by several groups, including the Islamic Renaissance Party — Tajikistan’s main opposition group operating in exile.The complainants allege that, over the years, Tajikistan has committed crimes against humanity, including torture, rape, extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detentions, and forced exile.Joining us is Steve Swerdlow, a human rights lawyer and professor of practice at the University of California, who has spent years researching Central Asia. I asked him how Tajikistan has changed over time, what the most striking human rights abuses committed by the regime are, and what we know about the details of the ICC case. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

This week, we’re exploring the archaeological excavations China has carried out in recent years in Central Asia—particularly in Uzbekistan—and the possible motivations behind these digs.Joining us is a special guest: Temur Umarov, a fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Centre who specialises in China–Central Asia relations. I spoke with him about how to interpret China’s interest in the region’s ancient and medieval history, what the Belt and Road Initiative (also known as the New Silk Road) really is, and what China’s broader goals are in each Central Asian state. Get full access to Turan Tales at turantales.substack.com/subscribe

Alexey Vinokurov never wanted to leave his hometown, Yakutsk, the coldest city on earth. Nested in Russia’s Siberia within the Republic of Sakha, it lies over 8,000 kilometres from Moscow and only 450 kilometres from the Arctic Circle. He found everything he needed there: a comfortable job as a graphic designer, a loving family, and lifelong friendships.But when Russia invaded Ukraine, his life unravelled. His Instagram posts condemning the war quickly led to two administrative convictions for discrediting the Russian army. Vinokurov knew that one more outspoken post could mean up to seven years in prison.His cousin, an IT specialist and former soldier, faced immediate danger. Ethnic minorities with military background like him were among the first drafted into Putin’s war. (Data from October 2022 shows that Yakutia residents were mobilised at 1.47 times the national target rate).Leaving the country became their best chance to escape the crisis. An opportunity soon emerged when Arsen Tomsky, the owner of inDrive – Yakutsk’s most successful IT company and employer of Vinokurov’s cousin – publicly condemned the war and made a bold announcement.InDrive would shift its Russia and Ukraine offices to remote work, offering employees an additional 20 per cent of their salaries to locate to safety. In the same Instagram post, Tomsky revealed that inDrive is “considering options to open a new office in a neutral country to support relocation of employees.”As it soon turned out, Kazakhstan emerged as the chosen destination. Most of Tomsky’s 1,000 Yakutsk employees relocated to the new Almaty office, now inDrive’s largest globally. Kazakhstan has since become a primary refuge for Sakha people seeking a new home outside Russia.Putting down roots“InDrive supported employees with apartment rentals, but affordable housing was scarce. So, some guys rented an old kindergarten, renovated it, furnished it with beds, mattresses, and linens, and created a free shelter for Yakutia residents,” says Vinokurov, who fled Russia in September 2022.“I knew nothing about Kazakhstan, but I was positively surprised. Stunning mountains, high-rise buildings, and a post-Soviet vibe. People began organising tours, and we realised this is a new hub for our people.”The Ginger Bar in central Almaty does not stand out amid hundreds other beer places in Kazakhstan’s former capital. The mostly Asian crowd which gathered there on a warm evening last September speak Russian, as is still the case in most Kazakh bars and restaurants. Except that none of the bar’s staff and clients was born in Kazakhstan.They are all Sakha. Unlike other migrants from Russia who flocked to Kazakhstan since 2022, the Sakha people have seamlessly integrated into Almaty’s vibrant social tapestry.The exact number of Sakha living in Kazakhstan remains uncertain due to a lack of official statistics. However, the Free Yakutia Foundation, a decolonial Sakha movement, told me that for their community it is “the most common destination.”In Almaty, Sakha have opened bars, restaurants, and shops, often blending in as Kazakhs. Only keen observers might notice that the tradition-inspired jewellery frequently worn by Sakha women differs from Kazakhstan’s popular ethnic accessories.The Sakha and Kazakhs share a nomadic heritage, Turkic language and the memories of Russian colonialism. By the 1840s, much of what is now northeast and central Kazakhstan was absorbed into the Russian Empire. In the 20th century, the Soviet Union sought to suppress Kazakh language and culture, and in the early 1930s, an artificial famine – triggered by land nationalisation and collective farms – claimed the lives of 1.5 million Kazakh nomads.In Yakutia, the colonisation concluded earlier. In 1632, Cossacks built the first Russian fort in the region. Sakha uprisings against the colonisers which took place from 1634 to 1642 were ruthlessly crushed. By the 18thcentury, Yakutia was fully absorbed into the Russian Empire, and the Sakha’s traditional nomadic and pastoral way of life was eradicated.In the 20th century, both Kazakhstan and Yakutia were home to numerous Gulags, Soviet labour camps used for punishment and exile of those deemed subversiveby the regime. During this period, both Yakut and Kazakh cultures were supressed in favour of the official Soviet one and new historical narratives.“Most of the Sakha people are unaware of their own history, but recent years have brought a surge in decolonial thinking and grassroot national initiatives,” says Egor, a historian and academic from Yakutia who relocated to Kazakhstan after Russia’s invasion. He requested anonymity to protect his family members still in Russia.“Our history includes several cases of resistance against the Russians, but research of these events is often censored – for example regarding the 17th century onset of colonisation. There is very little research and scholars tend to gloss over controversial points to avoid raising questions. For example, Russian historiography claims the civil war ended in 1924, yet partisan groups in Yakutia continued to operate into the 1930s.”In Yakutian schools, the history of the Sakha Republic was often an optional subject or was entirely omitted, Egor explains. He learned about his nation’s past through conversations with his grandparents and other elders. He pursued his own research as an academic, but since relocating to Kazakhstan, his work has stalled. Now employed at a private company, he has set aside his research pursuits.“I would like to live in Yakutia, work there, and bring a benefit to my republic. I miss the nature and food – frozen meat and fish. I miss my family and friends,” Egor says. “But I like Kazakhstan because of its open society. No one would attack you verbally on the street the way they do in Moscow and St Petersburg. There, I’ve always felt like an outsider. In Kazakhstan, I feel a cultural closeness.”Independence callingVinokurov, the graphic designer, shares Egor’s sentiment. He values Kazakhstan for the same reasons that he dislikes European Russia. After moving to Kazakhstan in autumn 2022, he met a Russian man from Tomsk, a former rocker, who, like him, sought to avoid being drafted to the front.Unlike Vinokurov, the Russian strongly supported Vladimir Putin. He wasn’t opposed to the war but had no desire to die in it. After a brief, respectful exchange of views and life stories, the man offered what he likely meant as a compliment: “This is the first time I’ve met a smart Asian.” Vinokurov, needless to say, was unimpressed.“He is a visitor here, yet this chauvinism does not leave him. Russians must understand that this is racism, they come to an Asian country and act superior to locals and all Asians,” Vinokurov said in an Almaty café. “They assume Asians are less intelligent, ignorant of politics and economics. This arrogance makes them imperialists.”In Almaty, Vinokurov says, he has never felt discriminated against or unwelcome. The locals speak a Turkic language, like the Sakha, and the winters are milder, far from Yakutia’s -50 degrees Celsius. Migrant life isn’t easy – he misses the nature, his family, and sometimes struggles to make ends meet – but such is the nature of starting anew, Vinokurov says.He hopes to return home someday, perhaps to an independent Yakutia that governs itself. Though Russia colonised his homeland a long time ago, Sakha still feel distinct from Moscow and it is not uncommon to hear them talk about independence.The Republic of Sakha ranks among Russia’s wealthiest federal subjects, boasting the fifth-highest gross regional domestic product (GRDP) per capita, just below Moscow. Rich in oil, gas, coal, diamonds, gold, and other vital minerals, it holds strong potential for self-governance.“With independence, we could trade gold, diamonds, and mineral resources,” Vinokurov says, acknowledging that the road to independence will be challenging.“People are tired of talking about politics, unsure what to believe or what the future holds. If we break away from Russia, many fear a civil war. On the other hand, the older generation worries that China will suddenly attack”.For now, Putin’s war has driven outward migration, draining the region of its brightest youth and its hard-earned status as an IT hub. Vinokurov notes that, compared to Kazakhstan, Yakutia’s young people face limited opportunities and their frustration grows.“Until recently, Yakutia had two major IT companies: MyTona and inDrive. We had a generation of programmers and IT specialists in peaceful, modern careers. Now, this sector is disappearing from Yakutsk,” Vinokurov says.“Once Yakutia gains independence, we will need to rebuild the IT sector. This will change people’s mindsets and reshape society”.For now, this vision will have to wait. Yakutia’s IT sector, like its brightest youth, is flourishing beyond the motherland.The face of Sakha ITAn image of Arsen Tomsky, Yakutsk’s beloved self-made billionaire, beams from the cover of his memoir at Meloman, Kazakhstan’s leading bookshop. Titled Inner Drive: From Underdog to Global Company it is available in both Kazakh and Russian. While the book was published over two years ago, it still holds a prominent spot in the commercial bookstore.The memoir recounts how a Yakutsk entrepreneur with a heavy stutter founded inDrive, a unicorn company, which refers to a startup valued over US$1 billion, and unlisted on stock markets. Today, inDrive operates in 888 cities across 48 countries.During a harsh Siberian winter in 2012, when taxi drivers hiked fares, local students launched an online platform connecting passengers with drivers. The main feature: both parties could negotiate the price.A year later, Tomsky, an established businessman, acquired the platform and launched inDrive, a ride-hailing app that retained the original negotiation model and charged less than 10 per cent commission – far below Uber’s 15-30 per cent cut.Tomsky aims to transform capital