Discover Weekend Sky Report

Weekend Sky Report

Weekend Sky Report

Author: WFYI Public Media

Subscribed: 10Played: 159Subscribe

Share

© 2024 WFYI Public Media

Description

Matt Pelsor is an astronomy geek. He loves observing the stars, planets and other celestial objects that fill our night sky. With his help, you'll discover the magic of the skies, from streaking comets to harvest moons, in the Weekend Sky Report archives.

114 Episodes

Reverse

This weekend, if we're lucky to get clear enough skies, check out one of the best moon phases

for lunar observation.

Right in the center of Taurus the Bull is the bright orange giant Aldebaran. Aldebaran is close… just over 60 light years away. And because of that, it’s easy to miss what’s behind it… about 90 light years behind it, to be exact. But even then, at over 150 light years away, the Hyades is one of the closest open star clusters. Compare that to the Pleiades at well over 400 light years away.

In Greek mythology, the Hyades are daughters of Atlas. As are the Pleiades… and following the death of their brother Hyas, their grief transformed them into stars. And their weeping for the loss of their brother… makes the rain.

When it’s not raining, you can see the Hyades by finding their sisters, the Pleiades in the eastern sky this evening. When you find the Pleiades, which is a cluster of bright blue stars you can easily see with the naked eye, look beneath it to find the bright, orange Aldebaran. Then grab your binoculars or any telescope and look straight at it… you’ll notice several bright white and yellowish stars just below and to the right of Aldebaran...and there you have it. The Hyades. Now, along with Aldebaran, the four brightest stars of the Hyades make up the head of Taurus the Bull. And since the Hyades is one of the closest and most studied open star clusters in the sky, we’ve known for a while why those four stars are so much brighter than the rest of the cluster. They’ve exhausted their core hydrogen and are evolving into giants. One of the final stages before their demise… in a few million years.

Observations of the bright, open cluster known as The Pleiades have been recorded since the 17th century BC, and likely even before that. It was scientifically and spiritually significant to many ancient cultures across the globe, and continues to educate and inspire observers today.

The Pleiades is a collection of B-type stars, which are bright, hot, and blue in color. And the stars of the Pleiades are close too—around 450 light years away, which contributes to its brightness. And while you don’t need a telescope or even binoculars to appreciate the Pleiades, it certainly helps.

The Pleiades is also known as the Seven Sisters, after the seven daughters of Atlas and Pleione in Greek Mythology. Observers with good eyesight under dark skies will count seven stars in the cluster. It wasn’t until Galileo looked at the Pleiades through his telescope that dozens of other stars were discovered. Since then, further scientific observations and subsequent calculations have estimated over a thousand stars in the cluster.

To see the Pleiades for yourself, look to the eastern sky in the evening—the later it is, the higher it will be. To the naked eye under suburban skies, it could be confused as a small cloud. Under darker skies, it’ll look more like a star cluster. Once you find it, grab your binoculars or a telescope. Once you look at the Pleiades with a little help, you’ll quickly realize why this star cluster has captured the human imagination for thousands of years.

Saturday night is the spookiest night of the year. Not just because it’s Halloween… but also because it’s a Halloween with a full moon. This sort of thing happens about once every 18 or 19 years. Less rare, but still pretty rare is the fact that it’s also a Blue moon, meaning it’s the second full moon in the calendar month. We get a blue moon about every 2.5 years. The last one we saw was March of 2018.

But because Halloween is the last day in a 31-day month, and the lunar cycle is 29-and-a-half days, every Halloween full moon is a blue moon.

And even though the full moon officially happens one night out of the month, it’ll appear full all weekend. On Friday night, it’ll rise just before 7pm. Saturday night, trick-or-treaters will be able to see it just above the horizon around 7:15. On Sunday night, it gets confusing because it’ll rise again before 7pm--yet another trick... the end of Daylight Saving Time.

Of course, the full moon through binoculars or a telescope can be fun, but if you’re looking for more treats, there are plenty of other bright targets to appreciate this weekend as well. In the evenings, bright orange Mars will be high to the southeast, while Jupiter and Saturn will be setting toward the southwest. Grab a telescope--any telescope--even good binoculars, and you’re likely to see Jupiter’s four largest moons, and the rings around Saturn.

So, if we’re lucky enough to have clear skies on Halloween, you’ll have plenty to scream about.

We all know about… the dippers. Ursa Major and Ursa Minor—the big and little dippers. We know about them because they’re out every night. But there’s another bright northern-hemisphere constellation you should know about… Swirling around the northern sky year-round are the five bright stars that make up… Cassiopeia.

Cassiopeia is popular with amateur astronomers because it’s large, bright, and the main reference point for several deep-sky objects. Things like Double Cluster, the Andromeda Galaxy, Messiers 52 and 103, both open star clusters, and the Owl Cluster, also known as the E.T. Cluster. Yes, THAT E.T. It’s called that because apparently it looks like the movie character. I don’t really see it, but I do enjoy finding it when I can.

Anyway, this weekend, you can find Cassiopeia high to the northeast after sundown. If you were to draw lines between its five bright stars, it would look kind of like a wonky lowercase “W” on its side.

Interestingly enough, if we were to take a quick trip to nearby star system Alpha Centauri, our own sun would appear in Cassiopeia. It would turn the “W” into a bit of a squiggle, and would be appear to be by far the brightest star in the constellation.

Cassiopeia has inspired novels, movies, TV shows, even songs. If we get a clear night this weekend, maybe look up for a little inspiration of your own.

While the moon is pretty to look at and easy to find, its light outshines a lot of deep sky objects. Galaxies, star clusters, nebulae… So moonless nights are what amateur astronomers live for.

One of the brightest deep sky objects, and therefore a good one to start with, is Messier 22--a globular cluster in the constellation Sagittarius.

M22 was one of the first globular clusters ever discovered. It was found by German astronomer Abraham Ihle (EEL-uh) in 1665, and later added to Charles Messier’s famous list of comet-like objects that we now know are immense, but distant and dim celestial objects. Not so dim though that today’s amateur telescopes can’t find them--especially M22. It’s one of the brightest of all globular clusters. Just about any telescope should reveal it, but you may have to look for a while before you find it. To do so, find Saturn and Jupiter--two bright points of light in the southern sky with Saturn on the left, and bright Jupiter on the right. Trace an imaginary line from Saturn to Jupiter, and continue that straight line about that same distance past Jupiter. Then with a telescope, any telescope, scan just a little further to the right and ever-so-slightly downward. When you see what looks like a fuzzy star, stop. You’ve found it.

Globular clusters are some of the best deep sky objects to start with because they’re easier to spot than galaxies and dimmer open clusters.

If you have any trouble finding Messier 22, find me on Twitter @MattPelsor for a visual guide.

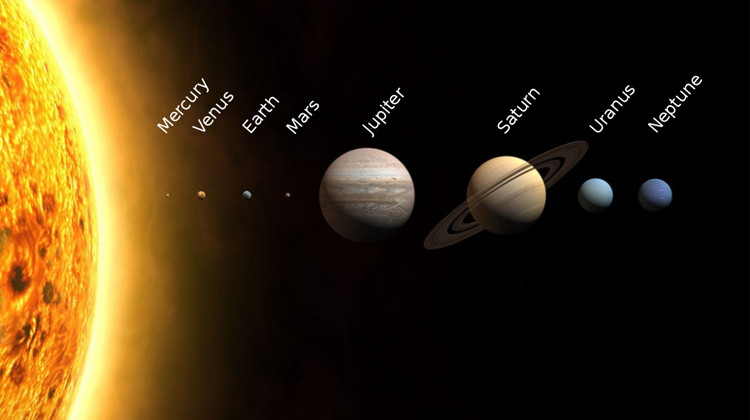

Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, AND Neptune will all be in the evening sky this weekend. And so will Pluto, if you still consider it to be a planet, but most amateur telescopes won’t have a chance of spotting it.

To see them all, you’ll need a decent telescope. To see the three brightest ones, you just need your eyes. Let’s go from East to West.

At around 10pm, you’ll notice a bright orange point of light in the night sky that doesn’t twinkle. That’s Mars, but further East, or to the left, is Uranus. In fact, it’ll be almost due east at ten o’clock, and slightly lower in the sky than bright Mars. Now, you can’t see Uranus with the naked eye unless conditions are perfect--dark skies and no atmospheric interference. And even then, it’s tough to spot. But with most telescopes you should be able to see something. If you spot a pale blue-green disc, you’ve found it.

Again, you can’t miss Mars… it’s bright, and has that distinct red-orange hue.

Now for the hardest one to spot… at 10pm, Neptune will be high to the south/southeast. You’ll need a large telescope to find it. Neptune wasn’t even discovered visually--it was discovered mathematically in the mid 19th century by studying the orbit of Uranus. Again, if you have a particularly good telescope, look for a dim, deep blue disc.

And to the southwest, you’ll see two brighter points of light that don’t twinkle. The dimmer yellow one is Saturn. Any telescope will reveal its rings. An amazing sight from your backyard. The brightest point of light to the west or right of Saturn is Jupiter. Binoculars should be enough to see its four Galilean Moons.

Oh, and Pluto? It’s right between Jupiter and Saturn… but you won’t be able to spot it unless you have an enormous telescope and know exactly what you’re looking for.

The moon will rise just after 8pm Eastern Time on Friday night. Just to the left of it will be a bright orange dot. The planet Mars. The two objects will be close enough that you should be able to see both in the same field of view through a modest pair of binoculars, depending on the magnification. Most telescopes get too close to see both in the eyepiece, but if you have a telescope--even a small toy telescope, you know just how striking the moon can be. If you haven’t gotten yours out in a while, get it out this weekend. Not only do you have the moon and Mars, but also Jupiter and Saturn. Jupiter is the brightest object behind the moon, but Mars isn’t far behind in brightness. Thankfully, Mars is on the other end of the southern sky, and has a distinctively orange hue. And of course it’ll be right next to the moon on Friday night, so there’s no confusing which one’s which. However, if you observe on Saturday or Sunday, look for Jupiter and Saturn due south around 8:30, and west of that if you go out later with Jupiter on the right and dimmer, yellowish Saturn on the left.

If you have a larger telescope, and you plan on being up late on Saturday night, scan just above and to the left of the moon with the scope and look for a light blue disc. That’s Uranus. And if you have a really big telescope, you probably already know that Neptune is also out and will be due south just after midnight.

So, with the right equipment, you can see all of the outer planets this weekend. But you’ll see half of them, plus Mars… with just your own two eyes.

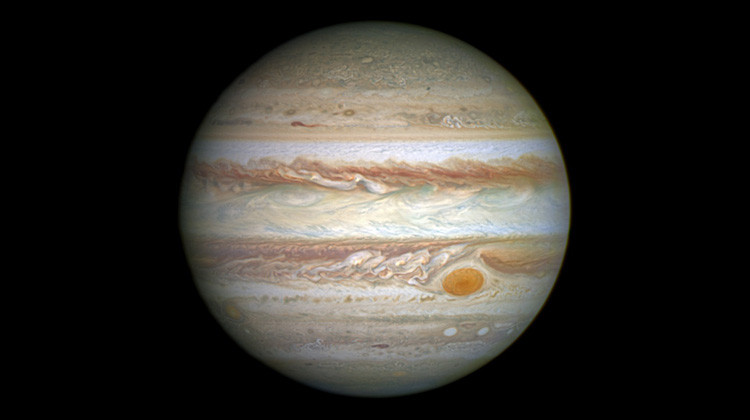

On Friday night, the moon rises just before 5pm, so by dark it will be high to the south/southeast. If you look at the moon on Friday night with a telescope or binoculars, look toward the shadow--what’s called the terminator, for details on craters and mountains--especially one of its more famous craters, the Tycho crater. One of the only craters you can really make out with the naked eye during a full moon--it’s the one with the spikes of impact ejecta coming off of it. On Friday night, that crater will fall right along the lunar terminator, so you’ll see a lot of good definition, including the central mountain peaks from the impact. Once you’re done looking at the moon on Friday night, you may notice a pale yellow point of light right above it. That’s Saturn. Just about any telescope, and even some binoculars will reveal Saturn’s rings and some of its moons. Larger telescopes will even show the Cassini Division--the dark gap between the two most visible rings. Once you’re done with Saturn, look just to the right, or further south for the second brightest object in the sky behind the moon. That’s Jupiter. A pair of modest binoculars will reveal its four largest moons--the ones Galileo discovered when he first looked at Jupiter through one of the earliest telescopes. If you have a larger telescope, you may want to observe Jupiter on Sunday night around 8pm when the Great Red Spot will be in view. Now these days, the Great Red Spot is more of a pale orange, but you can still make it out through decent telescopes with good magnification.

Oh, and Fall is a great time to watch the full moon rise. Look due East this coming Thursday October 1st just before 8pm for a dazzling show.

Tonight’s target has been known since LONG before the telescope was invented. This of course means it can be seen WITHOUT a telescope, but ONLY under very dark skies. And it wasn’t until the early 1800s that, THANKS to the telescope, it was identified as two separate clusters instead of one.

The aptly named Double Cluster is a favorite among budding amateur astronomers. Not only because its brightness makes it easy to find, but also because its beauty keeps observers coming back.

And here in the Northern Hemisphere, Double Cluster never dips below the horizon… so depending on your view, it’s out all night!

To find Double Cluster, look for Cassiopeia. You’ll find it in the northeastern sky in the evening. The later you’re out, the higher it will be... Cassiopeia looks like an elongated, oddly-proportioned “W.” Once you find it, look for the two stars closest together in the constellation. If the “W” were on its side, as it will be tonight, it’s the second and third stars from the bottom. Trace a line between those two stars, then scan down with binoculars or a telescope… following that same line. When you see a double cluster of stars, guess what… you’ve found it. Two brilliant clusters of mostly bluish white stars—but there are a few bright yellow and orange stars for variety.

When you find it, you’ll be looking at one of the younger star clusters you can easily find in the night sky… at only about 13 million years old. To give you an idea, Kangaroos evolved on Earth about two million years BEFORE these stars formed.

The brightest star in the constellation Perseus is Mirfak, and it’s where you need to look to find this weekend’s target.

The Alpha Persei (PER-see-EYE) Cluster is an open cluster of hot, bluish-white B-type stars. These kinds of stars are so energetic, they don’t live long. So most of the B-type stars we can see in the night sky are, on the cosmic scale, practically newborns.

In fact, by the time most of the stars of the Alpha Persei Cluster first formed, including the bright Mirfak, the dinosaurs were already extinct. Mirfak itself is less than 50-million years old, but it’s already entered old age. It’s a supergiant, having ballooned up to about 60 times the size of our sun. And it’s bright too—five THOUSAND times brighter than the sun.

To find Mirfak, and therefore the Alpha Persei Cluster, look to the northeast. You can find Perseus beneath Cassiopeia in the northeastern sky. The later it is, the higher it will be, but if you miss it this weekend, don’t worry. It will be to the northeast in the evening through early winter.

Under dark skies, you can see the cluster with the naked eye, but if you’re near the city, or if the moon is out, you’ll need some help. A small telescope or even a pair of binoculars should provide enough magnification to notice a loose cluster of bright blue stars around Mirfak. That’s the Alpha Persei star cluster.

The prominence of the constellation Perseus in the evening sky is a sure sign of autumn. It means you’ll be able to observe WITHOUT the help of bug spray… very soon.

Hiding in the constellation Cassiopeia… is a star cluster that goes by many names. Its most official name is NGC 457 for its place in Danish astronomer John Lewis Emil Dreyer’s New General Catalogue, a list of over 7,000 deep sky objects compiled in the late 19th century. But most people know it… as the Owl Cluster.

The Owl Cluster is an open star cluster, which is a group of stars that all formed around the same time in the same place, and are still bound together, though loosely, by their own collective gravity. The stars in the Owl Cluster are fairly young--all around 21 million years old. The ice caps on Antarctica have been around longer than these stars.

As you can probably guess from the name, the Owl Cluster resembles… an owl--when oriented a certain way. And you can see the Owl Cluster with almost any telescope… even cheap toy telescopes. Here’s how to find it. First, find Cassiopeia. Five bright stars that make a kind of funny sideways “W” in the north northeastern evening sky. Find the second star from the bottom, then look just above it with a telescope and slowly scan to the right. When you see a rich cluster of stars and those two unmistakable eyes… you’ve found it.

And when you see it, you’ll be looking at a cluster of stars more than 7,000 light years away… which means the light you’re seeing left those stars about a thousand years before the dawn of civilization.

On Friday night, the moon rises just before 6pm, so by dark it will be high to the south/southeast. If you look at the moon on Friday night, you’ll probably notice a bright point of light above it. That’s Jupiter. Grab a pair of binoculars or a telescope and have a look at the moon to admire some of its features. Look toward the shadow--what’s called the terminator, for details on craters and mountains, and then scan to Jupiter to see its four largest moons--the ones Galileo discovered when he first looked at Jupiter through one of the earliest telescopes. If you have a larger telescope, you may want to observe Jupiter on Saturday night after sundown when the Great Red Spot will be in view. Now these days, the Great Red Spot is more of a pale orange, but you can still make it out through decent telescopes with good magnification.

And by the way, on Saturday night, the moon will have moved East of not only Jupiter, but also Saturn in the night sky. Saturn is that pale yellow point of light just to the left of Jupiter. On Saturday night it will be just above and to the right of the Moon. Saturn’s another great target for smaller telescopes and good binoculars. The rings of Saturn are an incredible sight from your backyard. Looking at the Moon on Saturday though, you’ll notice one of the brightest features on the lunar surface right near the edge of the lunar terminator--the Aristarchus crater. A deep crater in the Northern hemisphere. Just follow the shadow until you see it.

The moon isn’t full yet--that’s not until Tuesday, but it’ll look pretty close on Sunday night. It’ll rise to the southeast around 7:30 on Sunday and be due south around Midnight.

So if we’re lucky enough to have clear or clear-ish skies, enjoy these bright targets.

Rho Cassiopeiae (row casio-pee-eye) is huge. More than 400 times the size of the sun and 40 times as massive. And did I mention it’s bright? Half a million times brighter. Now it’s by no means the MOST luminous star we’ve ever found, but it is one of the brightest yellow stars. Yellow stars, or Class-G stars are fairly common. Our own sun is a Class G. But Rho Cassiopeiae is a yellow hypergiant--a particularly rare and short-lived type of class-G star. They’re thought to be a type of star that evolves from a red supergiant to a hotter blue star. A strange evolution indeed in the celestial world. So even though we’ve known about this particular star for centuries, this huge, bright, yellow stage in its evolution is relatively brief. Strangely massive stars like this have short lives. Rho Cassiopeiae is probably no more than 6 million years old.

To find it, find Caph--the second-brightest star in Cassiopeia. It’s also the highest star in the constellation in our current evening sky--and the one furthest to the right if you were to turn Cassiopeia on its side so it looks like a W. From Caph, scan to the right and up with a telescope or a decent set of binoculars until you see a yellow star. Consult a star chart to make sure you have the right one.

Of the hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way, we’ve only found a dozen yellow hypergiants like Rho Cassiopeiae. So if you see it, you’ll be looking at one of the rarest star types we’ve ever discovered.

The Perseid Meteor Shower is great not only because it falls among the warmest nights of the year, so you don’t really have to bundle up to see it. But also because it’s one of the most frequent showers, producing up to 110 meteors per hour at its peak. That’s a meteor almost every thirty seconds.

Now, chances are you’ve seen a bright meteor streak the sky at some point in your life… and you’ll see a few of those this weekend, but most will be fast, and dim, so it’s important to find dark skies if you want to see the most meteors.

Now there’s one thing that can really ruin a meteor shower no matter how far out in the country you go to watch it… the moon. If the moon is out, its brightness will wash out the dimmer, more frequent meteors. Luckily, the moon doesn’t rise until around 3:30am on Saturday morning, and it won’t be up until after 4am Sunday morning.

They’re called the Perseids because they appear to emanate from the constellation Perseus, but you don’t really have to know where that is to know where to look. Here’s a good rule to follow. Just look to the northeast. That’s pretty much all you need to know. The earlier you’re out, the lower to the horizon the meteors will be, but the northeastern sky is the general target.

When you watch the meteors this weekend, you’ll be watching tiny particles—most of them smaller than a grain of sand, as they streak through the atmosphere and burn up… for our viewing pleasure. Dusty remnants of a comet called Swift Tuttle, which comes around about once every 133 years. Oh, as always, don’t forget the bug spray.

The weather doesn’t look great this weekend, but if we’re lucky enough to have clear or clear-ish skies, look the southeast after sundown… so around 9:30.

You’ll see that the moon dominates the evening sky this weekend. It’s a waxing gibbous moon, which means it’s on its way to being a full moon, which happens Monday.

When you look at the moon tonight, you’ll notice a bright point of light nearby. That’s Jupiter.

On Friday night, Jupiter will be below and to the left of the moon. Saturday, the moon sits between Jupiter and Saturn, which will look like a dim yellow star to the left of the moon. Sunday, the moon moves past both planets and closer to the horizon in the evening.

All three of these targets are great for observing with a telescope. Just about any telescope will allow you to point out certain features on the moon… and because there’s still a bit of a shadow covering part of the moon, you might notice really fine details on craters and mountains.

And speaking of moons… scan over to Jupiter with your telescope to see the four Galilean moons that orbit the giant planet.

They’re called Galilean moons because when 17th Century astronomer Galileo Galilei first observed Jupiter with his telescope, he noticed what he first thought were stationary stars. But when some would disappear in front of, or behind the planet, he concluded that they were orbiting Jupiter.

Ganymede, Io, Callisto, and Europa are the largest of Jupiter’s nearly 70 natural satellites. And you can see them this weekend… even with just a toy telescope.

And of course, seeing the rings of Saturn from your backyard is enough to hook anyone on astronomy. (Most telescopes, including that old one of yours will give you a pretty good look at that too.)

There’s a lot in the sky this weekend for anyone with binoculars or a cheap telescope. For one thing, the crescent moon will rise higher in the southwestern sky with each passing day until it reaches its first quarter phase on Sunday evening. A quarter moon--what some call a half moon--is one of the best phases to view through a telescope because the shadow, or lunar terminator, appears to move the fastest across the moon’s surface during this phase. So fast that you can sometimes actually see surface detail like craters and mountains illuminate in real time if you watch long enough.

But the object everyone’s talking about is Comet NEOWISE. To find it, imagine the Big dipper is horizontal with the cup to the right. Then imagine another cup underneath that one to get the spacing right. Scan underneath that imaginary Big Dipper cup slowly with binoculars. When you see a dim, fuzzy, blueish light, you’ve found it.

If you’re up for more after looking at the Moon and Comet NEOWISE, turn to the southeast for two bright planets--Jupiter and Saturn.

Jupiter is the brightest object in the sky behind the moon, so you should have no trouble finding it. Through decent binoculars, you may be able to see Jupiter’s four largest moons. If you have a larger telescope with lots of magnification, you may be able to see Jupiter’s Great Red Spot On Sunday night around 11pm when it will be in the center, facing Earth.

A little to the left, or East in the sky is a pale yellow dot that doesn’t twinkle. That’s Saturn. Most telescopes should reveal the planet’s famous rings.

Suffice to say there’s plenty to see this weekend, but don’t forget the bug spray.

If you have dark skies, you can see Comet Neowise with the naked eye, but urban and most suburban observers will probably need some help spotting it.

The largest planet in our solar system is clearly visible late at night. It rises to the southeast just after sunset, and it’s highest right around 2am, so if you’re up late, go out and look. By the way, most decent binoculars and almost any telescope--even a toy telescope should show you the four Galilean Moons, Ganymede, Io, Callisto, and Europa. They’re the four largest of Jupiter’s 70+ natural satellites, and Ganymede is the most massive moon in the entire solar system. The moons will look like four stars flanking the planet on either side, though you may not see all of them.

Jupiter is very bright right now, but it will technically be at its brightest this coming Tuesday when it’s at opposition, meaning the Earth is directly between Jupiter and the Sun. Now, that said, you probably won’t notice any difference between observing Jupiter tonight versus Tuesday night. But if you do look at Jupiter on Tuesday night, you might see one of its most famous features… the Great Red Spot.

Jupiter spins faster than any other planet. It completes a rotation every 10 hours. Because the Great Red Spot is a single feature on the planet, you have to go out at just the right time to see it. Lucky for us, 11pm eastern time Tuesday night will give us that opportunity. At that time, the Great Red Spot will be dead center. And while it may be called the Great Red Spot, it's more of a pale orange these days, so it’s hard to contrast against the whites and browns of the cloud belts unless you know where to look. And don’t get frustrated if you don’t see it. You need good observing conditions and a decent telescope with lots of magnification to get a good enough view.

But if you see it, you’ll be looking at a hurricane the size of Earth that, for all we know, has been raging for more than 300 years.

If you get a chance to look up at the moon this weekend, you may wonder what you’re looking at. Where did the Apollo missions land? What’s that big crater called?

Looking at the moon with the naked eye, you’ll notice a few big features. The so-called “seas,” the large ‘Ocean of Storms’ to the west, Even the Tycho crater to the south.

But look closer with a telescope—even a pair of binoculars, and the moon REALLY reveals itself.

You’ve heard of the Sea of Tranquility. That’s the dark area to the northeast as you’re facing the moon. If you’re ON the moon, it’s the northwest, but we’re not, so let’s stick with our own perspective. The sea of Tranquility is a sort of figure-8-shaped dark patch surrounded by other circular and oval-shaped dark patches—also known as seas. The sea of serenity to the northwest, the sea of fertility to the southeast, the smaller Sea of Nectar due south, and the sea of Crises to the east. I love the names.

The seas on the moon are actually volcanic plains made of basalt. The Sea of Tranquility is significant because it’s where the Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the first manned mission to the moon. The Apollo 11 landing site is at the southwest edge of the Sea of Tranquility. Now, you won’t be able to see any evidence of the landing with a personal telescope, but large professional land-based and space-based telescopes can spot the leftover hardware, and you can find those images with a simple internet search.

Scan west to the Ocean of Storms and you’ll see two prominent craters named after 16th century astronomers. Kepler and Copernicus. Both are all by themselves in the Ocean of Storms. The larger Copernicus is east of Kepler.