New play ‘Kyoto’ looks at the global agreement that first aimed to curb greenhouse gas emissions

Description

Hurricane Melissa devastated Jamaica and Cuba two weeks ago, bringing with it a short but deadly storm to New York City that killed two people in flash floods. With the world seeing stronger and more frequent weather events 28 years after the signing of the Kyoto Protocol — a global agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions — many crucial questions remain unresolved. And yet, the United States under the Trump administration withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement twice, one of the follow-ups to the Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 2015.

“Where the science is so obviously very, very clear and established, it is very odd to hear politicians from whatever country talk about anything to do with climate denial,” said Stephen Daldry, who co-directs the play “Kyoto,” “when it is obviously and has been, without question, established as a factor of a climate emergency around the world.”

The new play recently debuted in New York at the Lincoln Center and looks at that landmark agreement that took place in Japan nearly three decades ago. It’s set in the conference rooms where more than 150 delegates from around the globe attempted to come to a consensus about setting legally binding targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions — a moment that took 10 years to reach.

<figure class="wp-block-image size-large">

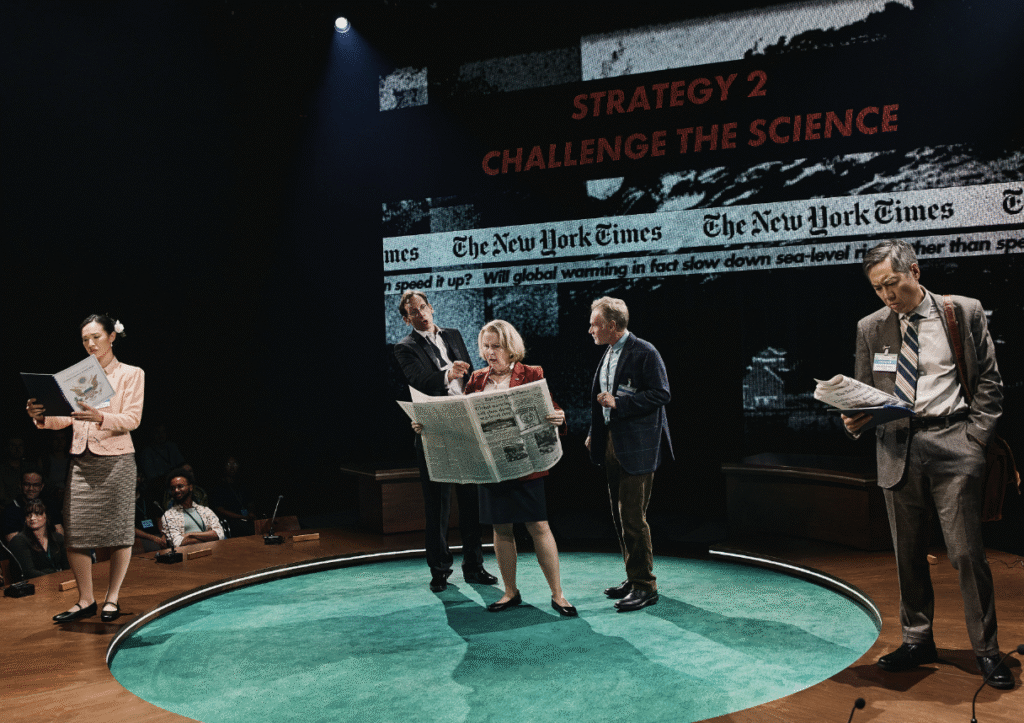

<figcaption class="wp-element-caption">The Kyoto Protocol brought more than 150 delegates from around the world together in 1997 to come to a consensus about setting legally binding targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.Courtesy of Emilio Madrid</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption class="wp-element-caption">The Kyoto Protocol brought more than 150 delegates from around the world together in 1997 to come to a consensus about setting legally binding targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.Courtesy of Emilio Madrid</figcaption></figure>The production presents tense arguments and the compromise that was needed to get to a document that everyone could agree to and sign.

Joe Murphy, one of the co-authors of the play, said that “the intention wasn’t to write about climate change. It was actually to try and tell a story about polarization, about those divisions that really run through our societies at the moment that feel so intractable.”

Along with Joe Robertson, Murphy embarked on a three-year journey researching the road to “Kyoto” and fell in love with UN Climate negotiations, ”which doesn’t sound like the most conventional ingredients for a thrilling night at the theater,” Murphy said laughing. “But in the people we spoke to, scores of diplomats and delegates and scientists, we just found this amazing devotion and commitment and dedication to the craft of multilateral negotiations. And a huge amount of emotion and pride in the work that they have done, for many of them, for most of their lives.”

They noticed gallows humor that can only come from whole nights spent at the negotiating table arguing about commas and the placement of verbs. “And we just went: How can we bottle this and put it on a stage?”

<figure class="wp-block-image size-large">

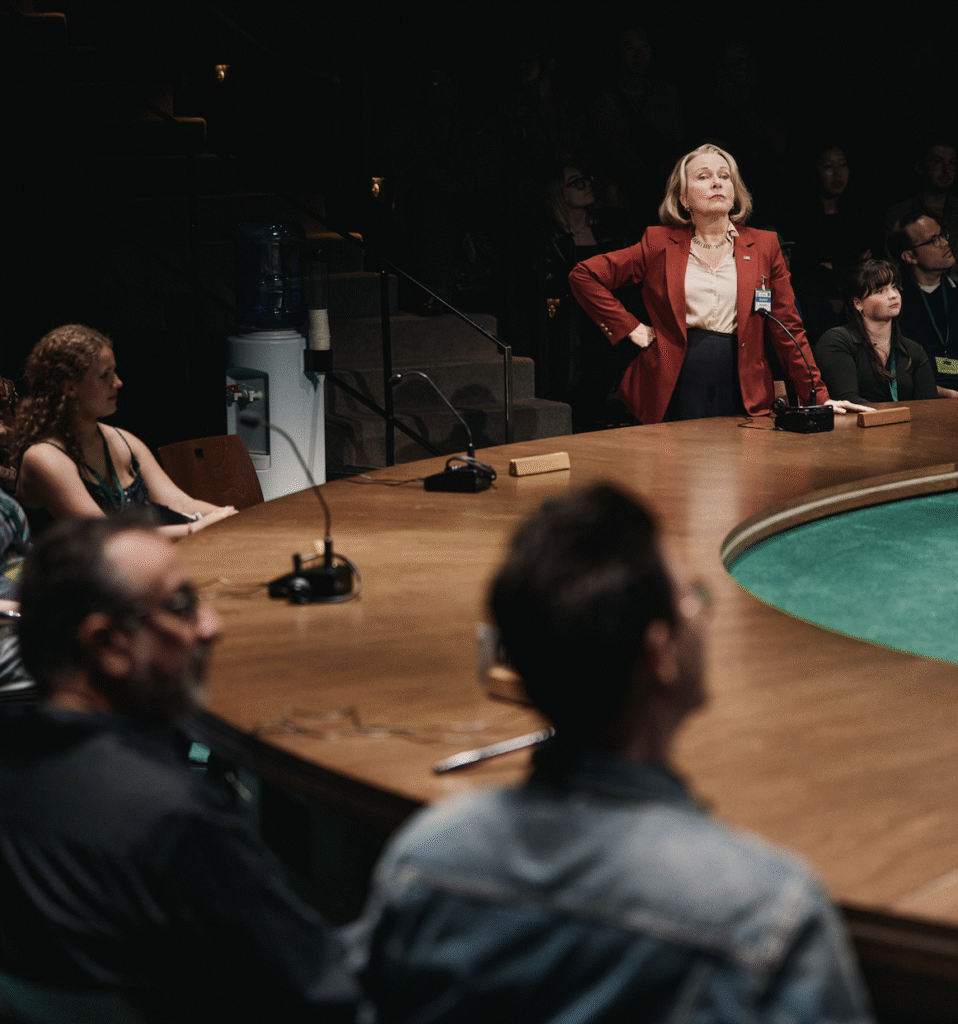

<figcaption class="wp-element-caption">The play “Kyoto” tells a story about polarization and the divisions that run through societies over climate change.Courtesy of Emilio Madrid</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption class="wp-element-caption">The play “Kyoto” tells a story about polarization and the divisions that run through societies over climate change.Courtesy of Emilio Madrid</figcaption></figure>There are some humorous but important scenes in the play about punctuation: brackets, conditional tense, commas.

“As a writer, a comma is used to create clarity for a reader,” Murphy explained. “But in climate law, a comma can be used to create ambiguity, because its placement between clauses or the absence of a comma between clauses can create enough ambiguity that two separate parties, two separate countries, are able to go back to their own governments and claim victory.”

The staging puts the audience right in the middle of the action.

“The set is designed as a sort of UN table, a bit like the Security Council or the General Assembly,” Murphy said. “It’s this circular table with microphones and headphones, listening to translations. And we wanted to invite the audience to take a seat at the table.”

Some audience members even sit right next to the actors around the table.

Don Pearlman, a little-known lawyer who worked in the Department of Energy under President Ronald Reagan, does everything he can as an oil lobbyist to throw sand in the gears.

<figure class="wp-block-image size-large">

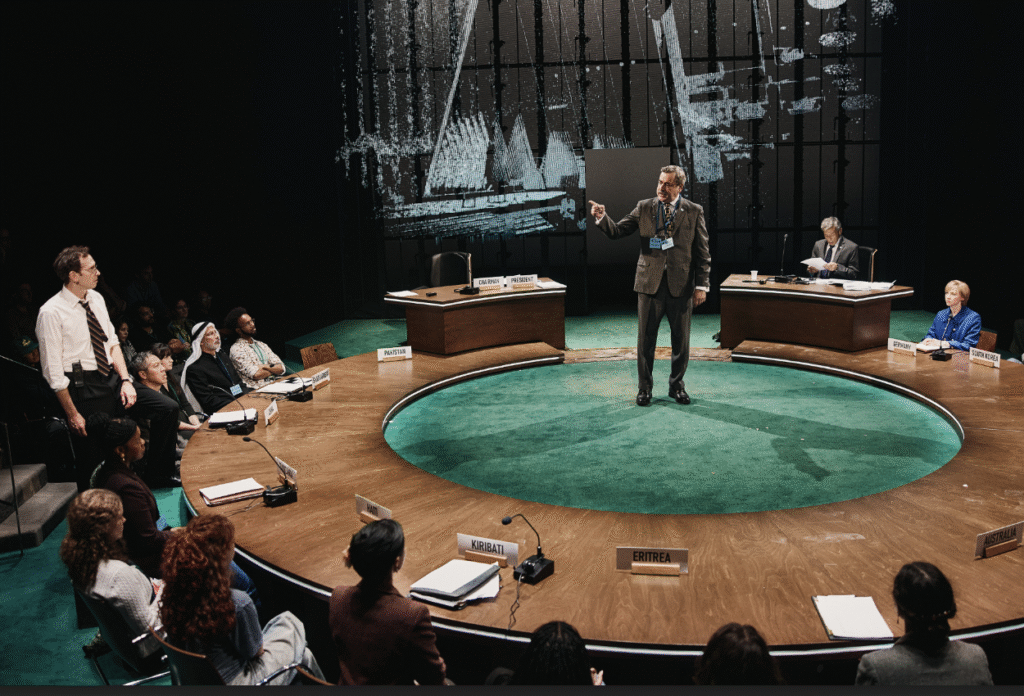

<figcaption class="wp-element-caption">With the unique staging set-up, some audience members end up sit right next to the actors around the conference table.Courtesy of Emilio Madrid</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption class="wp-element-caption">With the unique staging set-up, some audience members end up sit right next to the actors around the conference table.Courtesy of Emilio Madrid</figcaption></figure>“Don is such a useful foil,” said co-director Justin Martin. “What I love is the moments of the show in which he reflects us back to ourselves. Because he does make you think about our own carbon footprint and our own contradictions.” At one point, he explains how much carbon the participants use flying from their countries to the conference.

Stephen Kunken plays Don. “One of the beauties about performing a character is getting inside of that person and not judging them but trying to find the connective tissue to that person,” Kunken said. “Ultimately the point of drama is to humanize it. You know, that’s what makes it different from a documentary. I talked with Don’s son, Brad, at length, who is an incredible resource.”

At the other end of the spectrum is Raul Estrada, the Argentine ambassador who became the chair of the annual UN climate conference. He believes in the science and insists on keeping everyone at the table, even if it means working overnight without translators. The actor who plays Estrada, Jorge Bosch, pays tribute to him at every performance.

“He wears his tie onstage, the actual tie that Estrada wore in Kyoto,” said co-author Joe Murphy. “And that’s his little nod to the real man behind the character.”

<figure class="wp-block-image size-large">

<figcaption class="wp-element-caption">The staging puts the audience right in the middle of the action of the play.Courtesy of Emilio Madrid</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption class="wp-element-caption">The staging puts the audience right in the middle of the action of the play.Courtesy of Emilio Madrid</figcaption></figure>Even though the show builds to an agreement that the audience already knows about, it’s still a shock and relief when they come to a consensus. Some have considered the Kyoto Protocol a failure — the US Senate didn’t ratify it and other countries followed suit. But Murphy said that, in retrospect, the ability for the world’s countries to come together for a moment — even if it didn’t last — is a goal worth striving for.

“We hope Kyoto shows how that is still possible,” he explained. “You know, multilateralism isn’t dead. But it’s about the will to agree and the will to move forward and to make the difficult compromises. So, I feel hopeful … and that might be a weird thing to say.”

If this doesn’t feel like a satisfying ending, Murphy and Robertson say it’s only the first play in a trilogy to include the Paris Accords.

The post New play ‘Kyoto’ looks at the global agreement that first aimed to curb greenhouse gas emissions appeared first on The World from PRX.