Publishing Mistakes You Don’t Want to Learn the Hard Way

Description

</figure>

</figure>The transcription of this podcast is brought to you by the Christian Indie Publishing Association.

When I was growing up, my dad often said, “Success is a poor teacher, but failure is a cruel teacher.”

It’s far less painful to learn from someone else’s failures than to live through those cruel lessons yourself.

It can be hard to find authors who are willing to talk honestly about their failures in the publishing world. But I recently interviewed an outlier.

Daeus Lamb has made mistakes in his writing and publishing journey, and he’s willing to share those experiences so other authors can learn from them. He’s an epic fantasy novelist and the Director of Outreach and Community at StoryEmbers.org, a site dedicated to helping Christian storytellers enthrall readers through exceptional storytelling that honestly depicts God’s reality.

Mistake #1: Hiring a professional editor too late.

Thomas Umstattd, Jr.: What was the first lesson you learned the hard way on your publishing journey?

Daeus Lamb: For years, I wrote without seeking any education or help from professional writers, editors, or coaches. My beta readers gave fantastic feedback, but I never paid for a coach or an editor.

When I finally launched my first lead magnet and hired an editor, I was blown away by how much I needed to grow and how much I grew through the process of working with the editor.

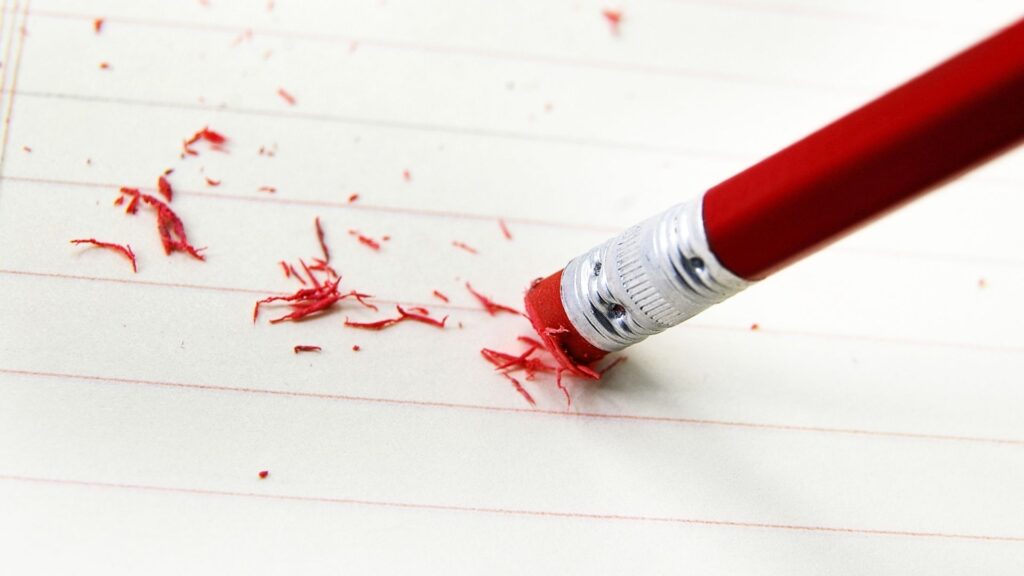

It was like taking a college course in writing. We worked through pages of red lines and completely rewrote the lead magnet. Since then, my writing has never been the same. It was a turning point in my writing career.

I came away thinking, “Why didn’t I spend $200 to hire an editor for a short story three years ago?” I know I wouldn’t have been able to publish it. I wasn’t that good then. But I would have grown so much. In one month of working with a professional editor, I learned more than I did in six months of pounding away on my own.

Thomas: The Boy Scouts say, “One week of canoe training is better than a lifetime of paddling around the lake.” You can use the same bad techniques your whole life without realizing they’re bad techniques.

There’s a big difference between practice and deliberate practice. People talk about the 10,000-hour rule, which comes from the famous book Talent Is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else (Affiliate Link). The author points out that in the time between a person’s breakout success and their starting point, they performed about 10,000 hours of deliberate practice.

Some authors take that to mean they just need to write for 10,000 hours, and then they’ll be a success. But if those hours aren’t filled with deliberate practice, you won’t improve much.

If you have a coach giving you feedback, you can improve your skill with every hour of practice. Your “coaching” can simply come from reading a book on craft or reading your writing aloud. That refining practice can be painful, but if you’re not challenging yourself to get better, you’re not practicing deliberately.

When we had Jerry Jenkins on the show, he told us he wrote an entire novel without using attribution tags in the dialogue. He didn’t publish it, but it was an act of deliberate practice to help himself become a better writer. That’s the kind of challenge that transforms regular practice into deliberate practice.

Even after Jenkins has sold millions of books, he’s still working to improve his craft.

Daeus: My lead magnet was only a novella; and by the time we were through editing, I was used to hearing the same corrections, and I learned the lessons. I wrote them down. I memorized them. I didn’t need to spend $2,000 to learn those lessons from my edited novel. I learned them through working with my editor on a much shorter novella.

Mistake #2: Starting with an epic novel, rather than a short story.

Thomas: If you’re not writing short stories, you are making your writing life a lot harder. Learn how to write short stories, and then write the longer works.

Daeus: I didn’t write enough short stories. I wrote two full novels from the omniscient point of view, which is the old style of many classics. I wrote that way because I had read so many classics. It wasn’t until my third novel that I figured out I wasn’t very good at it.

If I had written more short stories, I’m sure I would’ve figured that out earlier. You can’t just write ten short stories. You have to try different things in those short stories to push yourself and find out what you’re good at.

It’s also easier to get feedback on short stories. If I ask a beta reader to give feedback on a huge novel, I’m asking for a huge commitment. People are much more likely to agree to read and give feedback on a short story.

Thomas: I encourage every novelist to write one short story in each of the three major points of view just to try it out and learn what each feels like. You probably naturally default to one of the three main points of view: omniscient, first-person, or third-person. If you force yourself out of your comfort zone, your writing will dramatically improve.

You don’t have to publish them or sell them to an anthology. The stories are simply an exercise in improving your craft. And who knows? You may discover you like writing in first-person.

Daeus: I encourage writers to try different genres too. I was inspired to use the omniscient point of view because I like the classics. But now I’m an epic fantasy novelist, and I love it.

Mistake #3: Believing that fast writing is poor writing.

Daeus: I have wasted thousands of hours believing that if I write fast, surely I must be writing poorly.

Thomas: That misconception has an evil twin who says, “If you’re writing slowly, you must be writing well.”

Daeus: I used to write less than 500 words per hour. I was a slow, slow writer. The surprising catalyst for helping me write faster was that I got a full-time job. I had been working part-time; and when I started working full-time, I thought my writing time would be gone.

But I still had a little time each evening, and I had to figure out how to write these massive epic fantasy novels in less time. The only solution was to write faster.

I bought Chris Fox’s book How to Write 5,000 Words Per Hour (Affiliate Link), and I was skeptical. I’m sorry to say, I don’t write 5,000 words per hour; but my writing speed did triple in three days.

Thomas: That is such a common story. I’m starting to believe there are two kinds of writers: those who’ve tried Chris Fox’s courses and methods and those who tell themselves it’s impossible, so they won’t even read the book.

I’ve interviewed Chris Fox multiple times, and he believes that getting into the zone helps you write faster and better. Learning how to get into that zone makes you better and faster. If you’re not in the zone or only taste the zone occasionally, spend some time learning how to get into the zone more consistently. It can dramatically transform your writing.

Daeus: I was writing slowly because there was so much fluff and junk in my head. To write faster, I got rid of unnecessary thoughts.

Mistake #4: Having too much time to write.

Daeus: I started writing when I was 17 years old. I was living at home for free without many bills. I figured that if I wanted to be a full-time writer, I’d need plenty of writing experience to achieve excellence and build a platform.

Unfortunately, as you now know, I was writing slowly and wasting time; but it didn’t feel like it at the time. It felt like the right thing to do.

I worked a part-time job, and the hours weren’t predictable. I was paying for some expenses and building some savings, but it wasn’t much.

If I could relive those years, I would get a part-time job where I worked about 20 hours a week; and I’d try to earn at least $10,000 per year. I would spend that money on editors, writing coaches, and courses so that I could get professional feedback right away.

The time limit that comes with having a job launched me into learning to write faster. If I had had less time to write, I think I might have done even more writing.

Thomas: The same principle applies to authors at the end of their careers.

Som