Shakespeare's Hand in 'Sir Thomas More'

Update: 2025-11-10

Description

By Brad Miner.

Scholars have long known that Elizabethan drama was a collaborative business. Yes, a play by Ben Johnson, Christopher Marlowe, or William Shakespeare rightly belongs to each named author as the principal hand behind it. But there were often other hands involved as well.

A playwright delivered his script to the Lord Chamberlain's Men, say, and the various writers, directors, and actors (some performing all those tasks) would read and comment on the play. They'd debate the work's clarity, power, eloquence, humor, and, as a company, pound out a finished version the audience would see. Sometimes it didn't end there: if a jibe fell flat in a performance, they'd revise it. It happens on Broadway today - during rehearsals and previews.

We know this happened 400 years ago by analyzing original manuscripts that have survived (more or less) intact. Most are handwritten. (The famous First Folio - a printed version of Shakespeare's plays - appeared seven years after the Bard's death.) One such handwritten manuscript is Sir Thomas More (c. 1591-93).

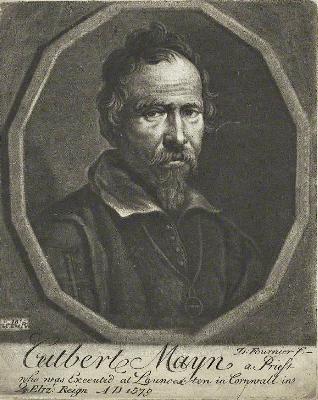

You may not have heard of it. The principal author has long been thought to be Anthony Munday, who likely collaborated with Henry Chettle, and not just Chettle. Thomas Heywood, Thomas Dekker, and William Shakespeare also had a hand in it. Literally.

There is a three-page section of the manuscript, written in cursive by "Hand D," that graphologists recognize as Shakespeare's handwriting. It's a speech given to More himself, in which the martyr-to-be calls for tolerance of foreign immigrants.

Any play about Thomas More was ill-fated less than a half-century after the death of Henry VIII. More had been martyred on Henry's order (July 8, 1535), and Elizabeth I's censors refused to allow a play about More to be performed.

Shakespeare was at the start of his career and some years from the great fame he'd achieve, although he was noticed: the playwright Henry Greene called him "an upstart Crow." Of course, Shakespeare would prove to be rather more than the country bumpkin Greene disdained.

Anthony Munday was several years older than Shakespeare, and there was an odd connection between them. The militant Protestant Munday had gone to Italy in 1578 as a spy to infiltrate Rome's English seminary, and evidence there (the Venerable English College) indicates that Shakespeare also visited a few years later, although not to spy. Munday then was openly anti-Catholic, and Shakespeare was secretly Catholic, so surely, they couldn't possibly work together! Yet they did.

Sir Thomas More tells the story of More's career as a public official. Its central irony is More's dedication to the King - indeed, his assertion of the necessity of obedience to Henry VIII - and the deadly consequence to More when he was unable to obey Henry in the "King's great matter."

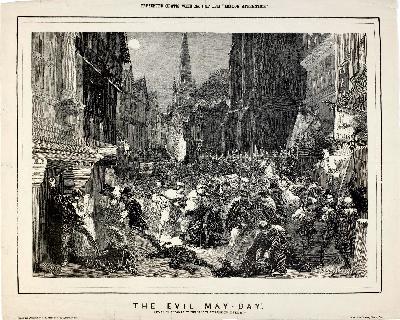

The play begins on May 1, 1517, known to history as Evil May Day, when Londoners rose up against immigrants.

A character grouses about the strangers: "Our country is a great eating country; ergo, they eat more in our country than they do in their own." Another joins in: "Trash, trash; they breed sore eyes, and tis enough to infect the city with the palsey."

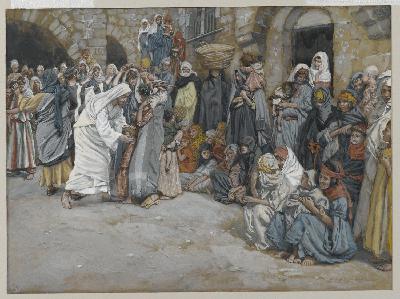

A riot is brewing until. . .Enter Thomas More, Sheriff of London. "Peace! Peace," the rabble cry. They'll listen to him. In a speech very much like Marc Antony's in Julius Caesar, More warns, woos, and sways them:

Grant them [the immigrants] removed, and grant that this your noise

Hath chid down all the majesty of England;

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs and their poor luggage,

Plodding to th' ports and costs for transportation,

And that you sit as kings in your desires,

Authority quite silent by your brawl,

And you in ruff of your opinions clothed;

What had you got? I'll tell you: you had taught

How insolence and strong hand should prevail,

How order should be quelled; and by this pattern

Not one of you should live an aged man,

For other ruffians, a...

Scholars have long known that Elizabethan drama was a collaborative business. Yes, a play by Ben Johnson, Christopher Marlowe, or William Shakespeare rightly belongs to each named author as the principal hand behind it. But there were often other hands involved as well.

A playwright delivered his script to the Lord Chamberlain's Men, say, and the various writers, directors, and actors (some performing all those tasks) would read and comment on the play. They'd debate the work's clarity, power, eloquence, humor, and, as a company, pound out a finished version the audience would see. Sometimes it didn't end there: if a jibe fell flat in a performance, they'd revise it. It happens on Broadway today - during rehearsals and previews.

We know this happened 400 years ago by analyzing original manuscripts that have survived (more or less) intact. Most are handwritten. (The famous First Folio - a printed version of Shakespeare's plays - appeared seven years after the Bard's death.) One such handwritten manuscript is Sir Thomas More (c. 1591-93).

You may not have heard of it. The principal author has long been thought to be Anthony Munday, who likely collaborated with Henry Chettle, and not just Chettle. Thomas Heywood, Thomas Dekker, and William Shakespeare also had a hand in it. Literally.

There is a three-page section of the manuscript, written in cursive by "Hand D," that graphologists recognize as Shakespeare's handwriting. It's a speech given to More himself, in which the martyr-to-be calls for tolerance of foreign immigrants.

Any play about Thomas More was ill-fated less than a half-century after the death of Henry VIII. More had been martyred on Henry's order (July 8, 1535), and Elizabeth I's censors refused to allow a play about More to be performed.

Shakespeare was at the start of his career and some years from the great fame he'd achieve, although he was noticed: the playwright Henry Greene called him "an upstart Crow." Of course, Shakespeare would prove to be rather more than the country bumpkin Greene disdained.

Anthony Munday was several years older than Shakespeare, and there was an odd connection between them. The militant Protestant Munday had gone to Italy in 1578 as a spy to infiltrate Rome's English seminary, and evidence there (the Venerable English College) indicates that Shakespeare also visited a few years later, although not to spy. Munday then was openly anti-Catholic, and Shakespeare was secretly Catholic, so surely, they couldn't possibly work together! Yet they did.

Sir Thomas More tells the story of More's career as a public official. Its central irony is More's dedication to the King - indeed, his assertion of the necessity of obedience to Henry VIII - and the deadly consequence to More when he was unable to obey Henry in the "King's great matter."

The play begins on May 1, 1517, known to history as Evil May Day, when Londoners rose up against immigrants.

A character grouses about the strangers: "Our country is a great eating country; ergo, they eat more in our country than they do in their own." Another joins in: "Trash, trash; they breed sore eyes, and tis enough to infect the city with the palsey."

A riot is brewing until. . .Enter Thomas More, Sheriff of London. "Peace! Peace," the rabble cry. They'll listen to him. In a speech very much like Marc Antony's in Julius Caesar, More warns, woos, and sways them:

Grant them [the immigrants] removed, and grant that this your noise

Hath chid down all the majesty of England;

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs and their poor luggage,

Plodding to th' ports and costs for transportation,

And that you sit as kings in your desires,

Authority quite silent by your brawl,

And you in ruff of your opinions clothed;

What had you got? I'll tell you: you had taught

How insolence and strong hand should prevail,

How order should be quelled; and by this pattern

Not one of you should live an aged man,

For other ruffians, a...

Comments

In Channel