The 1992 Election Through a Child's Eyes

Description

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, like many Christian families in California, my family became fairly politically active.

People in our small social circle of conservative homeschool families often lamented just how “awful” California was becoming. Our politicians weren’t representing us well and were turning our state into a cesspool of oppressive government, high taxes, punitive regulation, and ever-increasing crime.

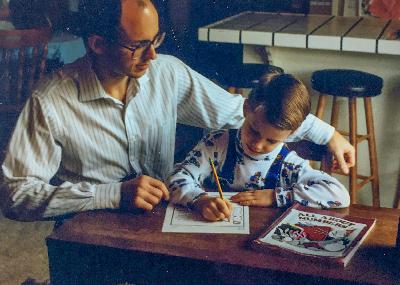

So, my dad, who had never held elected office before, decided to get involved in politics for the first time. He started small: in 1990, he founded a group called Citizens for Responsible Education, which vetted a few candidates to run for the local school board, backed them financially, and helped manage their campaigns.

I was just five years old at the time, but I still have vivid memories of that whole season of life that started back then. In addition to learning all about local elections with school boards (which was kind of ironic, if you think about it—we were homeschoolers, after all), my dad also supported a few races in the California State Assembly, U.S. Congress, and U.S. Senate.

I learned a lot about the political process as I sometimes spent evenings and weekends helping my dad volunteer for various campaigns. We screen-printed signs, posted those signs on the side of the road, stuffed envelopes and mailers, and walked door-to-door, handing out flyers for candidates.

As far as I recall, I was never really asked if I wanted to be a part of all this; I think it was just assumed that I would help. It was a family affair. I don’t know that I would have said “no” if I’d been asked, but I didn’t understand what it all meant and why we were doing it in the first place.

So many of the things people discussed and the words they used were totally foreign to me. What was a “cannadate,” anyway? Why did people who were in charge of schools call themselves a “school board?” And weren’t “principals” in charge of schools?

My very literal brain pictured a big sheet of plywood—a board—that said “school” on it; when I found out that school board members weren’t even teachers themselves, that made even less sense to me.

There were so many words thrown out by people who thought apparently it was all so completely normal, but I was often confounded upon hearing terms like: elections, budgets, deficits, primaries, taxation, districts, surveys, polls, precincts, voter registration, and even legislation.

What did it all mean? What were educational vouchers, the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Three Strikes Law? Why were we talking about baseball in politics? And why were people so passionate about things like this, to the point where they’d argue and even get angry about them?

The only thing that was clear to me was that some people were “for” certain things, while others were “against” them. I didn’t always have time to figure out what that meant, but I asked my dad to explain this whenever I could.

“Dad, what are ‘Mello Roos?’ Are they good or bad?” I’d ask.

If my dad supported an issue, it made sense that I’d support it, too—it would surely be the “right” position. After all, my dad was a “good guy.” He was a Republican. That meant Republicans were good, so I was probably a Republican, too.

The inverse seemed just as logical. If the other guys were against an issue we supported, they were taking the “wrong” position. If they were against my dad, they were “bad guys.” Those people were usually Democrats, so that meant Democrats were bad guys.

Micron is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

But I found out my dad didn’t exactly see it that way. He would correct me and say: “They’re not ‘bad guys.’ They’re our ‘opponents.’” This made little sense to me, and I wondered why we’d be opposing other politicians if they weren’t bad guys. Despite all the baseball metaphors, this wasn’t just a game after all; this was a moral battle of right and wrong.

Isn’t politics all about good guys fighting bad guys? I had assumed so, and I still thought so, even though my dad said it didn’t quite work that way.

Of all the things we did to help support our candidates, going door-knocking was, by far, my least favorite activity. Usually, I’d go out with one or two adults, and we’d hit the road with giant stacks of flyers and door hangars.

Walking for blocks at a time, we had big lists of registered voters that someone else on our team had previously highlighted, with each address color-colored. We knew who was and wasn’t registered to vote, which houses had Democrats, which had Republicans, and which had unaffiliated voters.

Based on our list, we’d hand out different types of literature. If we knew the residents of one address were Republicans, we’d give them a large, glossy door hanger with one particular message on it that had nice, full-color photography. These cost us a lot of money to produce, so we had to give them out very carefully.

If we knew they weren’t Republicans, we’d leave behind a smaller door hanger with a different, shorter message. These were printed on much uglier “highlighter green” paper with black smudgy ink that was much cheaper to print.

I didn’t mind simply placing a door hanger on the knob and walking away, but we weren’t allowed to do that: we had to actually knock on the door. Every time I knocked on a door, I winced, hoping nobody was home.

We had a rule that went something like: “If you knock three separate times, and nobody answers, you can just leave a hangar on the door.” I always wished nobody was home so I could just knock, place my flyer on the door, and run away.

(Sometimes, I admit, I would cheat, inflating my numbers by pretending to have knocked three times when I’d only knocked once or twice. I’m sorry, Dad.)

More often than not, though, someone was actually home. I always hated it when people came to the door. Usually, they were nice, and they’d open the door but leave their screen door closed and ask us what we wanted in a very defensive manner.

I would tell them I was passing out flyers for Richard Pombo or Dan Lungren (US Congress), Larry Bowler (California Assembly), Tom McClintock (US Senate), or Mel Panizza (Stockton City Council).

Depending on their political views, they might then open the screen door and step outside to talk to us. They’d tell us about who they voted for in the past or what their concerns were about the current election.

On occasion, people were nasty. They’d open their door just a crack and angrily shout: “What do you want? Are you selling something? Go away!” and slam the door.

One thing I learned very quickly going door to door was how I could immediately find out which houses had dogs. If a family had a dog in the house, the dog would start barking either when it detected me walking toward the house or the second I knocked on the door or rang the doorbell.

Side note: if I hadn’t already hated dogs by this point, this experience certainly cemented my disdain for them. Walking up to a stranger’s house to talk to people I didn’t know, who didn’t want to talk to me, about topics I didn’t fully understand was already hard enough… but it was made worse by vicious-sounding dogs that I thought wanted to bite me or kill me.

The ONLY thing that made going door-to-door worthwhile was how, after a long stretch of walking and knocking, there was a prize at the end: we would get a soda at the local gas station. Give me a 32 ounce icy root beer, and I was as good as new.

At the end of the election cycle, some of our candidates won their elections, and some didn’t. In my mind, this was hard to comprehend: we had worked equally hard for all of them, and they all seemed to support the same issues, so there didn’t seem to be any rhyme or reason as to why one person would win, while another would lose.

This was my first introduction to just how fickle voters are during elections and how, in truth, there is zero “science” in “political science.” Elections are ultimately decided by all kinds of things, I have found, but logic and common sense are not among them.

After two years of my dad’s initial involvement in politics, he decided to jump in with both feet by running for the California State Senate.

This was a shock because, aside from his recent efforts backing other candidates, he had no personal political experience to speak of. The only time he had been elected to anything in the past was being elected as an elder at church.

(Once again, I heard the term “elder board” and pictured a bunch of old men sitting around a table made out of a giant board of wood… or something like that).

So, when he made the announcement that he would be running for office himself, that really surprised me. Looking back now, if I were an adult who wasn’t related to him, I would have advised him not to run at all. I’d have told him he would make a bad politician for one simple reason: he’s far too honest.

My dad is bold and direct; he’s willing to say things people don’t like to hear. In real life, that tendency helps make a man a good husband, father, and friend. But as a politician seeking elected office, it can often be career suicide. As I learned from an early age, despite all claims to the contrary, voters actually like politicians who lie to them.

Oh sure, they’ll say they don’t like lying politicians—they will rant, rave, and scream angrily about how much they don’t like those g*ddamned, no-good, lying scumbag politicians… but you want to know the honest truth? Most people actually require polit