Time in the Rock – Travails of a Composer

Description

Tragedy. “A drama typically involving a person destined to experience downfall or destruction, as through a character flaw, or conflict with some overpowering force such as fate or an unyielding society.”

Hubris. “An extreme and unreasonable feeling of self-confidence.”

Posthumous. “Published after the death of the author.”

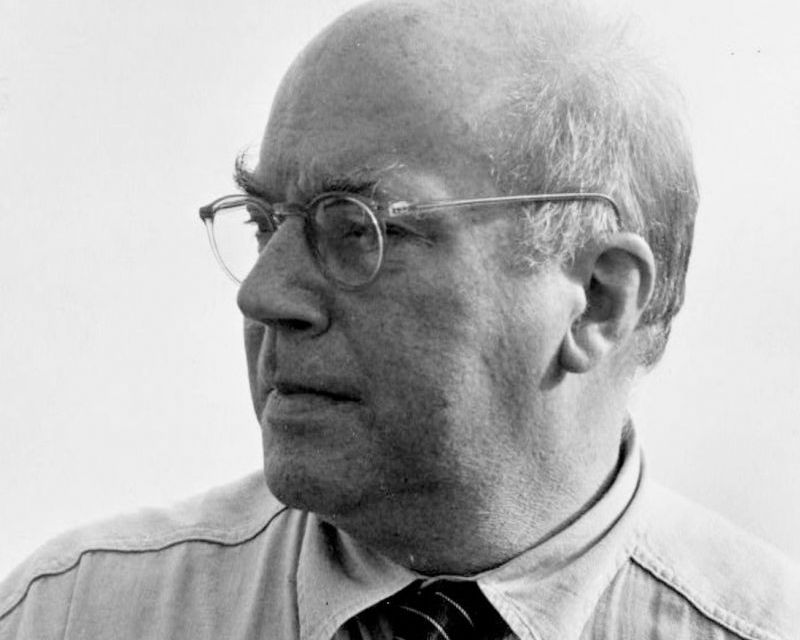

In May of 2001 I began work on the most ambitous composition project of my career. I had long been enamored of the poetry of American author Conrad Aiken, and previously, in 1998, already had made a setting of one of his poems for soprano, piano, vibraphone, marimba, glockenspiel and crotales – a piece titled Never in Word. Soon thereafter I began selecting and editing text from Aiken’s monumental serial poem Time in the Rock, written between 1932 and 1936. A grand series of 96 poems, the work at first was titled, and then subsequently subtitled, Preludes to Definition. It directly followed an earlier (1927-1931) series of poems originally titled Preludes to Attitude, subsequently retitled Preludes to Memnon. As Aiken first intended, both series were later published together as one book in 1966 by Oxford University Press with the simple title Preludes. The text I selected for the musical work was drawn from nine individual poems: numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, 24, 26, 31, 33 and 57, which I edited and ordered in my own way to suit the structure of the music I was planning.

Aiken’s formal poetic architecture, as well as his language, is often musically structured – in his words, “mathematically lyrical” (the series and the spiral being the most significant mathematical influences). Both the mathematical and the lyrical aspects of these structures connected directly to the means and techniques with which I had been working in my music for at least fifteen years (see “About the Music” for a description). Aiken’s poetry confronts, among other themes, individual and global human transformation – a spiritual, philosophical and ethical dilemma which has fascinated me for many years. Aiken’s perspective was that of a person living and writing in the late 1920s/early 1930s. The prevailing question was, as he expressed it: “…where was one to go, or what stand upon, now that Freud, on the one hand, and Einstein on the other, with the shadows of Darwin and Nietzsche behind them, had suddenly turned our neat little religious or philosophic systems into something that looked rather alarmingly like pure mathematics?” Similar concerns had been voiced and addressed before, of course – for example, in the aftermath of the discoveries of Descartes, Newton and Leibniz in the 17th century. At the beginning of the 21st century we again face a transformation to a new paradigm, this time in the wake of developments in physics, cosmology, biology and genetics. For the first time, however, humanity now seems to be in a position to control, change and expand not only the environment it inhabits, but also its very own physical, intellectual and emotional make-up. Direct neural connection to artificial forms of intelligence and data storage, bioengineered and genetically transformed physical bodies, and chemically enhanced and controlled emotional states are all in various stages of development. It is the first possibility (and, in my opinion, more a probability if not a certainty) of self-directed non-Darwinian evolution for a species on this planet. What course humankind should choose for this transformation is an enormously thorny problem for the coming century, but there was no question, in my mind at least, that a new form of human being eventually will appear to compete with, and ultimately replace, the present form. Aiken’s prescient words continue to address these issues in ways that resonate with an uncanny currency. Aiken considered Time in the Rock to be simultaneously abstract and analytic in “…its discussion…of the relationship between being and speaking: of the world and the word.” With that in mind, and from a musical perspective, I considered my piece to be a discussion of the relationship between being and listening: of the world and the song.

For the new work I chose an ensemble of string quartet, piano, vibraphone, marimba and four female vocalists – high and low soprano, and high and low alto. The piece would consist of four movements for voices and instruments, alternating with four rather extensive texts spoken by an actor/narrator. The narrated poetry is generally different in character from the texts used in the musical settings. The poem Time in the Rock moves freely between symmetrical verses in classic iambic pentameter and verse in a somewhat freer and more irregular style. I felt the classical metric verses demanded the use of a specific, yet ambiguous rhythmic meter, and I chose to use the odd meter of 7/4 throughout the entire piece. The much denser and discursive free verses, which are nevertheless critical to the central thoughts of the work, contain a great many words that need to be articulated and heard clearly – too many to be presented in a musical setting of less than Wagnerian proportion. For this I envisioned a professional male actor, who would speak the texts in dramatic monologues. The narrated sections would then present questions and introduce ideas, which would be subsequently elaborated and developed in the musical movements. In this way I considered the piece to be a kind of oratorio. The duration of the finished work came to approximately 50 minutes. The complete text for all eight sections of the piece can be viewed in the attachment HERE.

My decision to create a piece like this was the result of previous work with Aiken’s poetry as well as the desire to continue developing my own compositional ideas. I was not asked or commissioned to write a large theatrical work, and did not, at first, consider any of the practical issues that would surround mounting a public performance of such a thing. I approach composition from a developmental perspective, in that each new piece is informed by the materials, structure and orchestration of the previous ones, and often is influenced directly by the most recent work. I won’t accept a commission if the proposed piece can’t conform to the direction in which my work is going. In this case payment of any kind was a moot consideration. Time in the Rock was something I had to write at that stage of my composition work, and at that time in my life. I finished the piece in March of 2004.

After completing the score, I engaged a recording engineer and studio to create the best MIDI realization possible. At that time sample libraries were not as evolved as they are currently, but good ones featuring players from some major symphony orchestras were already available. The biggest obstacle to producing a quality MIDI recording was the problem of voices singing text. The only available option was to use the sound of “oohs” and “ahs” as a substitute. Nevertheless, I was able to make a demo CD of the complete work, excluding the narrated texts, which I assumed could be read along with the missing lyrics by anyone interested in the piece. I considered the MIDI demo to be a first step toward organizing and financing a premiere.

First movement: And There I Saw The Seed (midi version)

The intent was for the work to be staged with austere lighting, a blue/violet psychlorama, matching silver-gray gowns for the singers (positioned on a riser behind the instruments and conductor), a contrasting outfit for the actor/narrator (positioned stage right with a separate spotlight), and individual amplification for each instrument and voice. Besides the actor, musicians and a conductor, the production would also require a sound tech, a lighting designer, and possibly a professional costumer. Obviously the venue would need to have the capabilities to accommodate such a staging. I had a few preliminary meetings with producers in Toronto where local venues like Roy Thomson Hall and Massey Hall were discussed.

As I was beginning to consider these practicalities, I wanted to confirm that the instrumental and vocal parts were correctly notated, and without any surprise problems for execution. I had learned the value of a preliminary review like this while working with the composer Steve Reich, who routinely previewed his orchestrations with individual performers before beginning rehearsals with a professional ensemble. I sent the score for Time in the Rock to two respected sopranos for review, one of them, Micaela Haslam, the director of the British vocal group Synergy, which I had in mind to provide the four female singers for my piece. Synergy’s director re