Discover The Rialto Report

The Rialto Report Wade Nichols: ‘Like an Eagle’ – His Untold Story Part 2: Disco! – Podcast 153

Wade Nichols: ‘Like an Eagle’ – His Untold Story Part 2: Disco! – Podcast 153

Wade Nichols: ‘Like an Eagle’ – His Untold Story Part 2: Disco! – Podcast 153

Update: 2025-06-22

Share

Description

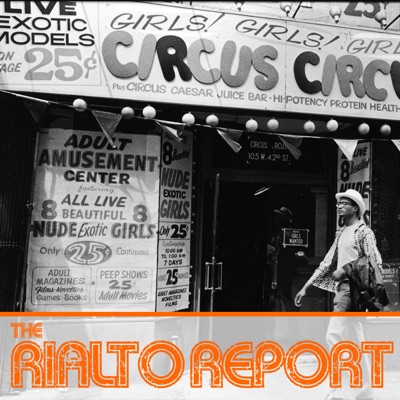

After a career in straight XXX films, Wade Nichols becomes disco star, Dennis Parker.

The post Wade Nichols: ‘Like an Eagle’ – His Untold Story Part 2: Disco! – Podcast 153 appeared first on The Rialto Report.

Comments

In Channel

United States

United States