What’s happening to the Anglican Communion?

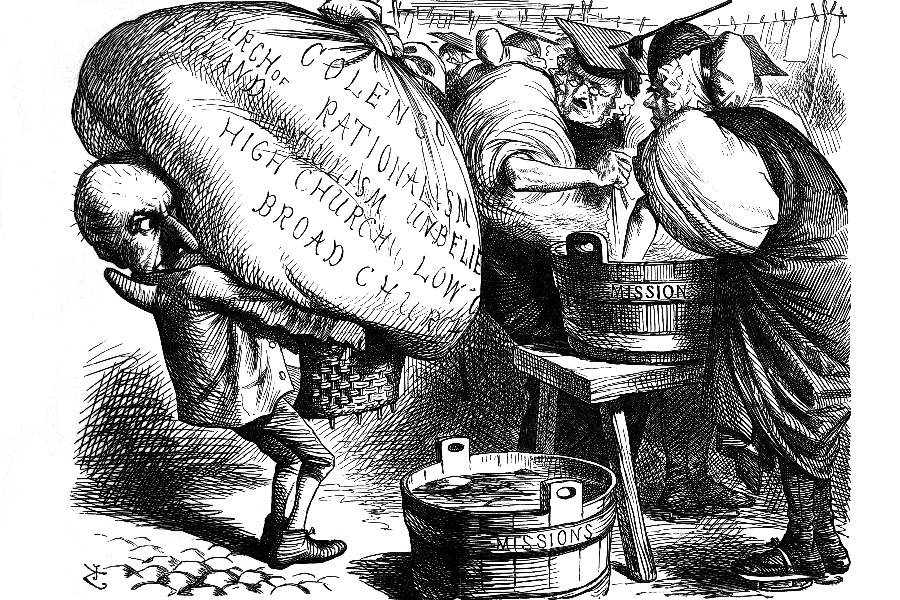

Description

Earlier this month, a body known as GAFCON — the Global Fellowship of Confessing Anglicans — declared it was “now the Global Anglican Communion.”

In the Oct. 16 declaration, entitled “The future has arrived,” the alliance of conservative Anglican church leaders said it had resolved to “reorder” the Anglican Communion, the world’s third-largest Christian communion after the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodoxy.

“Today, GAFCON is leading the Global Anglican Communion,” said the statement signed by Rwandan Archbishop Laurent Mbanda, chairman of GAFCON’s Primates’ Council.

“As has been the case from the very beginning, we have not left the Anglican Communion; we are the Anglican Communion,” he added.

What are the roots of the Anglican Communion? Where does GAFCON fit in? And what does its new declaration mean?

A communion’s roots

The Anglican Communion was born out of the missionary activity of the Church of England under the British Empire.

The Church of England — the established (state) church in England — believes itself in continuity with the Gregorian mission, the expedition commissioned by Pope Gregory I in 596 to convert the Anglo-Saxons, the inhabitants of what is now England. The mission was led by St. Augustine of Canterbury, a Rome-based monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in 597.

This Anglican conviction of continuity explains why Bishop Sarah Mullally was described as “the 106th Archbishop of Canterbury since St. Augustine arrived in Kent from Rome in 597” in the Oct. 3 press release announcing her appointment.

But the conviction is not accepted by Catholics, who point out that St. Augustine of Canterbury acted under the pope’s authority, used the Roman Rite, and introduced Roman liturgical practices to Britain.

For Catholics, the more relevant date is not 597 but 1534, when the English Parliament declared King Henry VIII the supreme head of the Church of England, breaking with Rome. From that point, the Church of England was a body separated from Rome and therefore in discontinuity with the Gregorian mission.

While early Anglicanism retained elements of the Roman Rite, the vernacular Book of Common Prayer, published in 1549, marked a decisive break (though it had a deep influence on Divine Worship, the missal used by the personal ordinariates, a Catholic body for groups of former Anglicans).

The Edwardine Ordinals of 1550 and 1552 changed the form of ordination, leading Pope Leo XIII to declare in his 1896 apostolic letter Apostolicae curae that they rendered Anglican orders “absolutely null and utterly void.”

The Church of England’s overseas expansion began in the American colonies, with Anglican churches established in Virginia from 1607 under the authority of the Bishop of London. The first overseas diocese was created in Nova Scotia in 1787, followed by Quebec (1793), Calcutta (1814), Jamaica (1824), Barbados (1824), and Cape Town (1847).

But the Anglican Communion didn’t come into being formally until 1867, when the then-Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Longley, invited 76 bishops from around the world to gather at his London residence, Lambeth Palace. This “pan-Anglican synod” became known as the first Lambeth Conference and was followed by similar meetings roughly every 10 years of the worldwide Anglican leadership with the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Lambeth Conferences were eventually defined as one of the four “instruments of communion” that bind the Anglican Communion. The other three are the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Anglican Consultative Council, a body of bishops, priests, and laity that has met regularly since 1971, and the Primates’ Meeting, which has brought together leaders of national Anglican Communion provinces since 1979.

The communion today has 85 million members belonging to 42 autonomous provinces in 165 countries. Around 63 million are based in Africa.

Perhaps the greatest mistake Catholics can make in understanding the Anglican Communion is to assume its structure is similar to that of the Catholic Church. It isn’t.

For example, it’s accurate to describe Pope Leo XIV as the Primate of Italy and head of the global Catholic Church. But as the Anglican lay theologian Martin Davie recently pointed out, it’s misleading to call the Archbishop of Canterbury the “head of the Church of England” and “head of the Anglican Communion.”

Official Anglican documents recognize no such positions, he observed.

“Thus, the ‘Governance’ page of the Church of England’s website describes the Archbishop of Canterbury as ‘the most senior bishop of the Church.’ It does not say that the archbishop is head of the Church