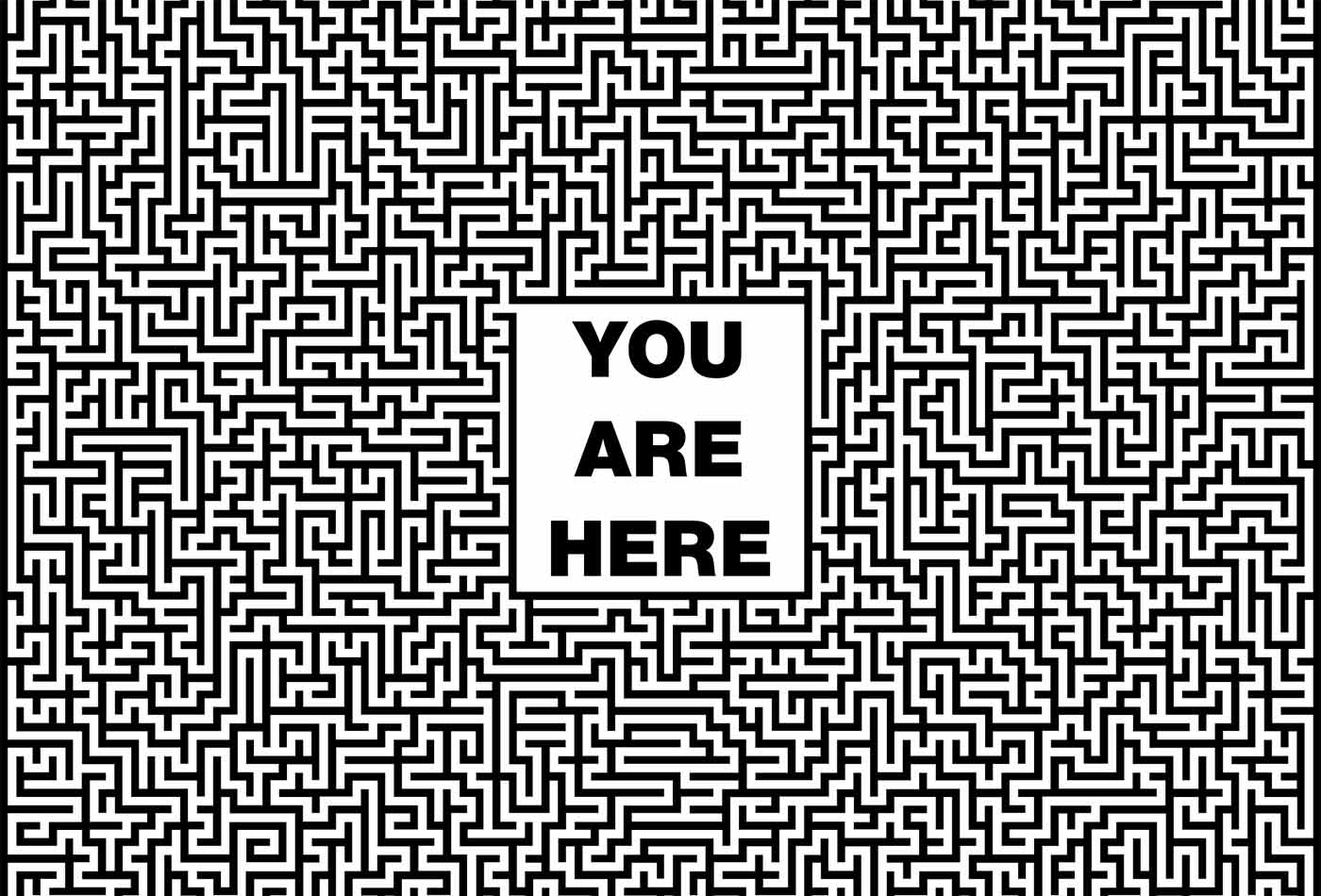

Why your attention is like a piece of contested territory

Description

In this episode of the Data Show, I spoke with P.W. Singer, strategist and senior fellow at the New America Foundation, and a contributing editor at Popular Science. He is co-author of an excellent new book, LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media, which explores how social media has changed war, politics, and business. The book is essential reading for anyone interested in how social media has become an important new battlefield in a diverse set of domains and settings.

We had a great conversation spanning many topics, including:

- In light of the 10th anniversary of his earlier book Wired for War, we talked about progress in robotics over the past decade.

- The challenge posed by the fact that social networks reward virality, not veracity.

- How the internet has emerged as an important new battlefield.

- How this new online battlefield changes how conflicts are fought and unfold.

- How many of the ideas and techniques covered in LikeWar are trickling down from nation-state actors influencing global events, to consulting companies offering services that companies and individuals can use.

Here are some highlights from our conversation:

LikeWar

We spent five years tracking how social media was being used all around the world. … We looked at everything from how was it being used by militaries, by terrorist groups, by politicians, by teenagers—you name it. The finding of this project is sort of a two-fold play on words. The first is, if you think of cyberwar as the hacking of networks, LikeWar is its twin. It’s the hacking of people on the networks by driving ideas viral through a mix of likes and lies.

… Social media began as a space for fun, for entertainment. It then became a communication space. It became a marketplace. It’s also turned it into a kind of battle space. It’s simultaneously all of these things at once, and you can see, for example, Russian information warriors who are using digital marketing techniques and teenage jokes to influence the outcomes of elections. A different example would be ISIS’ top recruiter, Junaid Hussain, mimicking how Taylor Swift built her fan army.

A common set of tactics

The second finding of the project was that when you look across all these wildly diverse actors, groups, and organizations, they turned out to be using very similar tactics, very similar approaches. To put it a different way: it’s a mode of conflict. There’s ways of “winning” that all the different groups are realizing. More importantly, the groups that understand these new rules of the game are the ones that are winning their online wars and having a real effect, whether that real effect is winning a political campaign, winning a corporate marketing campaign, winning a campaign to become a celebrity, or to become the most popular kid in school. Or “winning” might be to do the opposite—to sabotage someone else’s campaign to become a leading political candidate.

Related resources:

- Siwei Lyu on “The technical, societal, and cultural challenges that come with the rise of fake media”

- Supasorn Suwajanakorn on “Building artificial people: Endless possibilities and the dark side”

- Guillaume Chaslot on “The importance of transparency and user control in machine learning”

- “Overcoming barriers to AI adoption”

- Alon Kaufman on “Machine learning on encrypted data”

- Sharad Goel and Sam Corbett-Davies on “Why it’s hard to design fair machine learning models”