Discover The History of the Christian Church

The History of the Christian Church

250 Episodes

Reverse

This Episode is simply titled “Leo”While there’d been several bishops of the church at Rome who’d been capable leaders and under their guidance had established Rome as the premier church, if not the whole Christian world, at least in the western portion of the now declining Roman Empire, it can be fairly said that for most of the earlier bishops the person was eclipsed by the office. Bishops Callistus, Stephen, Damasus, & Innocent I all added significant authority to the Roman See. But it was Leo the Great who saw the Bishop of Rome become what we might call the first real Pope. It was with Leo I that the idea of the Papacy became real.While previous bishops at Rome had certainly been theologically astute, as befitted their office, Leo can be classed as a first-rate theologian, arguably the greatest theologian of any who came before in that office and for a century & a half after. He battled the Manichæan, Priscillianist, & Pelagian heresies, and won enduring fame for helping to finish codifying the orthodox doctrine of the person of Christ.Leo’s early life is shrouded in mystery. The chief source of information about him comes from his letters & they don’t commence till AD 442 when he was already an adult. Leo was mostly likely a Roman who became a deacon, then a legate under Bishops Celestine I & Sixtus III. A legate is a special messenger, sent by a bishop, to carry messages to civil rulers. Think à Church ambassador to the king. Leo was so astute in his task as a representative for the Church, Emperor Valentinian III sent him on a special mission to settle a dispute in Gaul between a couple feuding generals. This was at a time of great turmoil in the north due to the barbarian threat. While Leo was on this peace-making mission, Bishop Sixtus died and Leo was chosen to take his seat. He served for the next 21 years.Leo describes his feelings at the assumption of his office in a sermon;“Lord, I have heard your voice calling me, and I was afraid: I considered the work which was enjoined on me, and I trembled. For what proportion is there between the burden assigned to me and my weakness, this elevation and my nothingness? What is more to be feared than exaltation without merit, the exercise of the most holy functions being entrusted to one who is buried in sin? Oh, you have laid upon me this heavy burden, bear it with me, I beseech you be you my guide and my support.”Leo’s papacy faced 2 immense problems.First: The emergence of heresies threatened the integrity of the Church; and àSecond: The political disintegration of the Western Roman Empire.Leo offered 3 tactics in dealing with these difficulties à1) Actions to provide essential church doctrine with a clear, orthodox position;2) Efforts to unify church government under a sovereign papacy; and3) Attempts at peace by negotiating with the Empire’s enemies.On the doctrinal front, Leo theologically refuted the era’s main heresies & utilized imperial criminal prosecution & banishment to get rid of unrepentant heretics. Leo’s finest achievement was probably the formation and acceptance of an orthodox Christological dogma.Though Arianism was in retreat, the 5th C battled with what’s called Eutychianism. We’re going to get into this in more depth in a soon coming episode so for now let me just say that Eutychianism was one of the 4th & 5th Cs’ attempts to understand the nature of Jesus. Was He God, Man or both? And if both, how do the 2 nature relate to each other? Eutychianism said Jesus had 2 natures, human & divine, but that the divine had completely dominated the human, like a drop of vinegar is overwhelmed by the sea. Later it will come to be known by a label you may have heard = Monophysitism.Leo’s manner of dealing with this aberrant teaching was brilliant. Rather than rely on suppression, he brought it’s main advocate, Eutychus, to Rome for lengthy discussions and, after painstaking research & deliberation, issued a carefully written letter, the famous Tome of Leo. It set forth a clear exposition of Christ’s 2 natures in 1 person & became the basis in 451 for the Council of Chalcedon’s enduring formulation of Christological doctrine.This alone would mark Leo as worthy of the honorific “Great” but he did more, much more. He rescued the city of Rome from destruction, not once, but twice! When Attila & his Huns, known as the “Scourge of God,” destroyed the Italian city of Aquileia in 452 & everyone knew Rome was next on the barbarian’s hit list, Leo, with a couple companions, travelled north, entered the hostile camp, and persuaded Attila to leave off sacking the City. Think of it; a bishop’s simple word accomplished what the waning might of the once mighty Rome could not, convince the barbarian hordes to go home.Then, 3 yrs later when the Vandal king Genseric was poised to do what Attila had been deflected from, Leo was able to obtained a promise the Vandals would relieve the city of its wealth but not burn it or slay its people. The sacking lasted for 2 wks – but when the looters finally left, the city still stood and its citizenry, though badly shaken were still alive; and eternally grateful for Leo’s intervention.He died in 461, and was buried in the Church of St. Peter.The literary works of Leo consist of nearly a hundred sermons and over 170 letters. His collection of sermons is the first we have from a Roman bishop. He declared preaching to be his sacred duty. His sermons were short and simple.Leo was a man of extraordinary activity. He took a leading part in all the affairs of the Church. While his private life is unknown, there’s not a hint of anything that would give us cause to think he was anything other than pure in both motive & morals. His zeal, time & strength were all devoted to the interests of the Faith. If Leo saw the Faith primarily through the lens of the life & outreach of the Church at Rome, we ought to attribute that to his conviction Rome was meant by God to be THE Home Base for the Church; its headquarters.As Church historian Philip Schaff said, Leo was animated by an unwavering conviction God had committed to him, as the successor of Peter, the care of the whole Church. He anticipated all the dogmatic arguments by which the power of the papacy was later established. Leo made the case that the rock on which the Church is built, mentioned by Jesus in Matthew 16, meant Peter and his confession of faith, that set the cornerstone for THE Faith. Leo claimed that while Christ himself is in the highest sense the Rock and Foundation of the Church, His authority was transferred primarily to Peter. To Peter specifically, Christ entrusted the apostolic keys of the Kingdom. Also, Jesus’ prayer that Peter be strengthened so he might strengthen others established Peter’s role as leader among the Apostles. Jesus’ post-resurrection affirmation of Peter’s call, “Feed my sheep,” makes Peter the pastor and prince of the Church Entire, through whom Christ exercises His universal dominion on Earth.But Leo went further, He said Peter’s primacy wasn’t limited to the apostolic age; it endured in those subsequent bishops of Rome to whom Peter passed the authority Jesus endowed him with. Leo asserted only Rome could serve as the center of the Church because it was both a political & religious center. Sure, Constantinople was political headquarters but it lacked Rome’s spiritual ancestry. Alexandria & Antioch were religious, but not political centers. Only Rome provided a sufficient political and spiritual weight to be the center of the Earthly manifestation of the Kingdom of God.While Leo made much of Rome’s place as premier among the churches, he himself remained humble. This personal humility was offset by his determination others would honor his office as though he were indeed a modern Peter. Each year a special celebration was called to commemorate his ascension to Peter’s seat. He took such confusing titles as, “Servant of the servants of God,” “vicar of Christ,” and even “God upon earth.”As an aside, if you’ve read my bio on the sanctorum.us site, you know I’m a non-denominational, Evangelical, follower of Jesus. As I’ve shared in a previous podcast, it’s been interesting reading reviews by listeners that I’m obviously è Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Reformed, Pentecostal, & a few other flavors of the faith. I guess people mistake what my personal view is because I’m trying, albeit haltingly, to treat the material in as fair & unbiased a fashion as possible. So, I suspect here’s what’s happening in a lot of listeners minds right now after sharing Leo the Great’s apologetic for the primacy of Peter; they’re wondering if I’ve gone RC!Let me respond to that by sharing this . . .While Leo did make a good case for the Bishop at Rome being the spiritual successor to Peter, what about the fact that Peter himself passes over his primacy in silence. In his NT letters he expressly warned against hierarchical assumptions while Leo used every opportunity to affirm his authority. In Antioch, when Peter played the role of hypocrite, he meekly submitted to the junior apostle Paul’s rebuke. Leo, on the other hand, declared any resistance to his authority as an impious pride and sure way to hell. Under Leo, obedience to the pope was a condition to salvation. He claimed anyone not in harmony with Rome’s See as the head of the body, from which all gifts of grace descended, was in fact not IN The Church, and so had no part in grace or the Body of Chrsit.Schaff wrote,This is the fearful but legitimate logic of the papal principle, which confines the kingdom of God to the narrow lines of a particular organization, and makes the universal spiritual reign of Christ dependent on a temporal form and a human organ.Another important point: Crucial to the idea that the Bishop of Rome was & is the spiritual heir to Peter’s apostolic authority is the assumption Peter founded & led the Church at Rome. There’s simply not a shred of evidence for that. Sure, Peter went to

This episode is titled “Who Do You Say He Is?”We begin this episode by reading from the Chalcedonian Creed of AD 451, the portion devoted to the orthodox view of Christ.We, then, following the holy Fathers, all with one consent, teach men to confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, the same perfect in Godhead and also perfect in manhood; truly God and truly man, of a rational soul and body; consubstantial with the Father according to the Godhead, and consubstantial with us according to the Manhood; in all things like unto us, without sin; begotten before all ages of the Father according to the Godhead, and in these latter days, for us and for our salvation, born of the Virgin Mary, the Mother of God, according to the Manhood; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, only begotten, to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably; the distinction of natures being by no means taken away by the union, but rather the property of each nature being preserved, and concurring in one Person and one Subsistence, not parted or divided into two persons, but one and the same Son, and only begotten, God the Word, the Lord Jesus Christ; as the prophets from the beginning declared concerning Him, and the Lord Jesus Christ Himself has taught us, and the Creed of the holy Fathers has handed down to us.Compare that to the simple words of the Apostles Creed quoted by many Christians from memory 300 years before.I believe in . . . Jesus Christ, God’s only begotten Son, our Lord: Who was conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate; was crucified, dead and buried. He descended into hell. The third day he rose again from the dead. He ascended into heaven and sits at the right hand of God the Father Almighty. From thence he shall come to judge the living and the dead.Quite a difference. What caused the Church to draw such exacting language regarding who Jesus was between the early 2nd & mid 5th Cs? That’s the subject of this and the next episode. Along the way, we’ll see of interesting developments in the Church and learn of some colorful characters.In the 16th chapter of Matthew’s Gospel, we read of a time near Caesarea Philippi in Galilee when Jesus asked His disciples, “Who do people think I am?” After hearing what the popular talk was, Jesus asked them “Who do YOU say I am?” That set the stage for Peter to confess his faith in Jesus as Messiah.We might think Jesus’ affirmation of Peter’s reply would put an end to the controversy. It was only the beginning. That controversy raged over the next 500 yrs as Church leaders wrestled with HOW to understand Jesus.We’ve already touched on this subject in previous episodes. I’ve mentioned we’d return to deal with it specifically in a future episode. This is it; and here’s why we need to slow down a bit and take our time reviewing the history of the controversy over how to understand Who Jesus was. We need to camp here for a bit because this issue consumed a good amount of the Church’s intellectual energy during the 4th & 5th Cs.Today, we accept the orthodox view of the Trinity & the Nature of Jesus as God and Man readily; not realizing the agony the Early Church Fathers endured while they labored over precisely HOW to put into just the right words what Christians believe. One theologian said Theology is the fine art of making distinctions. Nowhere is that more clear than here; in our examination of how orthodox theologians described a Christ.The first great Ecumenical Council was held at Nicaea in 325 at the urging of the Emperor Constantine. Some 300 bishops representing the entire Christian world attended to hammer out their response to Arianism; the idea that Jesus was human, but not divine. As the Council dragged on, Constantine, itching to get back to the business of running the Empire, pressed the bishops to adopt a Statement that affirmed Jesus was both God & man. But many of the bishops left Nicaea discontented with the wording of the Nicaean Creed. They felt it was imprecise. It failed to capture the full truth of Who Jesus is. This lack of support for the Nicaean Creed opened the doors for many of the later controversies that would wrack the Church. The Council of Chalcedon 125 yrs later tightened up the language on Nicaea but didn’t fundamentally alter the Creed. Let’s take a look at the time between Nicaea & Chalcedon . . .Sometimes, in an attempt to bring clarity to a complex situation, we over-simplify. I run the risk of doing that here. But for the sake of brevity, I beg the listeners’ indulgence as I chart the path from 325 to 451.Following Nicaea, with the affirmation that Jesus is both God & Man, the Church had to first harmonize that with the Biblical reality there’s ONE God, not Two. And wait, someone asked, what about the Holy Spirit; doesn’t the Bible says He’s also God? The classic, orthodox statement of the Trinity, that God is 1 in substance or essence, but 3 in persons wasn’t something everyone immediately agreed to. It wasn’t like at the Council of Nicaea they took a vote and agreed Jesus is both deity & humanity. Then someone raised their hand & said, “Isn’t there just one God?”Yes. à Well, how do we describe God now? They waited in silence for 14 seconds, then someone said, “How about this: We’ll say God is one in substance & 3 in person.” They all smiled & nodded, slapped that guy on the back and said, “Good one. There it is; the Trinity! Our work here is done. Let’s go for pizza. I get shotgun.”No; it took a while to get the wording right. What made it difficult is that they were working in 2 languages, Greek & Latin. A formulation that seemed to work in Greek was hard to bring over into Latin, and vice versa.It took the work of the Cappadocian Fathers, Basil the Great of Caesarea, his younger brother Gregory of Nyssa, and their close friend Gregory of Nazianzus who worked out the wording that satisfied most of the bishops and framed the classic, orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. The Council of Constantinople was called in 381 to make this Trinitarian formulation official. This was just a year after Emperor Theodosius I declared Christianity the official State religion.So, with that piece of important theological business out of the way, they moved on to the next topic. And this is where it gets messy.If Jesus is both God & Man – how are we to understand that? Does He have 2 natures, or does 1 of the natures trump the other? Or is there a 3rd way: Did the human & divine natures fuse into a new, hybrid nature? And if Jesus IS a hybrid, do Christians get to drive in the chariot-pool lane?Lots of different camps put forward their scheme and fought hard to see their doctrinal formulation become the official position of the Church.The Council of Ephesus in 431 came out with a position that elevated 1 nature, while the Council at Chalcedon 20 years later altered that by affirming Jesus’s 2 natures.It became obvious to church leaders after the Council at Constantinople that the turmoil they saved in solving the problem of the Trinity was just added to the Christological problem that rose next.To understand how this issue was settled, we need to take a look at the rivalry that grew between 2 churches; a rivalry sparked in large part by Christianity being liberated from persecution and elevated to the darling of the State. Those 2 churches were Alexandria & Antioch.The debate over how to understand the Person & Natures of Jesus was staged in the Eastern Empire. The West wasn’t as involved because Rome simply did not see as much challenge on its belief in the dual nature of Christ. So while it wasn’t the scene of so much theological turmoil, it did play an important part in how the controversy was settled.Political rivalry between Alexandria and Antioch had been going on for some time. Being in the East, both churches vied with each other to provide Bishops to Constantinople, the New Rome & political center of the Eastern Empire. Getting one of their Bishops promoted to the capital meant bragging rights and could result in additional power & prestige for the Alexandrian or Antiochan sees. Two bishops from Antioch that were drafted by Constantinople were John Chrysostom, who we’ve already looked at, and Nestorius, who we will.In addition to their ecclesiastical jealousy, was the very different cultural and theological traditions in play at Antioch and Alexandria. The church at Antioch had a closer tie to the Jewish roots in Jerusalem. It had a stronger tradition of rational inquiry. It was at Antioch that church leaders had dug deeply in the OT to find many of the great types that pointed to Jesus. They studied Scripture through the lens of literal interpretation, rejoicing that God became Man in the Person of Jesus.The Church at Alexandria was different. It grew up under the influence of philosophical Judaism as seen in Philo and passed on to scholars like Clement & Origen. The Alexandrians had a tradition of contemplative piety, as we might expect from a church near the Egyptian desert where the hermits got their start and had been such stand-out heroes of the Faith for generations. In interpreting Scripture, the Church at Alexandria developed and was devoted to the allegorical method. This saw the truest meaning of Scripture to be the spiritual realities hidden in its literal, historical words.While the leaders at Antioch saw Jesus as God come as man, at Alexandria they agreed Jesus was a man, but His divine nature utterly overwhelmed the human so that He effective had only 1 operative nature; the divine.The differences between Antioch and Alexandria had already surfaced in their different approaches in refuting the error of Arianism. That they never reconciled them set the stage for all the acrimony to ensue over the debate on Jesus. The Arians made much of the NT passages that seemed to suggest Jesus’ subordination to God the Father. They liked to quote John 14: 28, where Jesus

The title of this episode is, “Can’t We All Just Get Along?”In our last episode, we began our look at how the Church of the 4th & 5th Cs attempted to describe the Incarnation. Once the Council of Nicaea affirmed Jesus’ deity, along with His humanity, Church leaders were left with the task of finding just the right words to describe WHO Jesus was. If He was both God & Man as The Nicaean Creed said, how did these two natures relate to one another?We looked at how the churches at Alexandria & Antioch differed in their approaches to understanding & teaching the Bible. Though Alexandria was recognized as a center of scholarship, the church at Antioch kept producing church leaders who were drafted to fill the role of lead bishop at Constantinople, the political center of the Eastern Empire. While Rome was the undisputed lead church in the West, Alexandria, Antioch & Constantinople vied with each other over who would take the lead in the East. But the real contest was between Alexandria in Egypt & Antioch in Syria.The contest between the two cities & their churches became clear during the time of John Chrysostom from Antioch & Theophilus, lead bishop at Alexandria. Because of John’s reputation as a premier preacher, he was drafted to become Bishop at Constantinople. But John’s criticisms of the decadence of the wealthy, along with his refusal to tone down his chastisement of the Empress, caused him to fall out of favor. I guess you can be a great preacher, just so long as you don’t turn your skill against people in power. Theophilus was jealous of Chrysostom’s promotion from Antioch to the capital and used the political disfavor growing against him to call a synod at which John was disposed from office as Patriarch of Constantinople.That was like Round 1 of the sparring match between Alexandria and Antioch. Round 2 and the deciding round came next in the contest between 2 men; Cyril & Nestorius.Cyril was Theophilus’ nephew & attended his uncle at the Synod of the Oak at which Chrysostom was condemned. Cyril learned his lessons well and applied them with even greater ferocity in taking down his opponent, Nestorius.Before we move on with these 2, I need to back-track some & bore the bejeebers out of you for a bit.Warning: Long, hard to pronounce, utterly forgettable word Alert.Remember è The big theological issue at the forefront of everyone’s mind during this time was how to understand Jesus.Okay, we got it: àThe Nicaean Creed’s been accepted as basic Christian doctrine.The Cappadocian Fathers have given us the right formula for understanding the Trinity.There’s 1 God in 3 persons; Father, Son & Holy Spirit.Now, on to the next thing: Jesus is God and Man. How does that work? Is He 2 persons or 1? Does He have 1 nature or 2? And if 2, how do those natures relate to one another?A couple ideas were floated to resolve the issue but came up short; Apollinarianism and Eutychianism.Apollinaris of Laodicea lived in the 4th C. A defender of the Nicene Creed, he said in Jesus the divine Logos replaced His human soul. Jesus had a human body in which dwelled a divine spirit. Our longtime friend Athanasius led the synod of Alexandria in 362 to condemn this view but didn’t specifically name Apollinaris. 20 Yrs later, the Council of Constantinople did just that. Gregory of Nazianzus supplied the decisive argument against Apollinarianism saying, “What was not assumed was not healed” meaning, for the entire of body, soul, and spirit of a person to be saved, Jesus Christ must have taken on a complete human nature.Eutyches was a, how to describe him; elderly-elder, a senior leader, an aged-monk in Constantinople who advocated one nature for Jesus. Eutychianism said that while in the Incarnation Jesus was both God & man, His divine nature totally overwhelmed his human nature, like a drop of vinegar is lost in the sea.Those who maintained the dual-nature of Jesus as wholly God and wholly Man are called dyophysites. Those advocating a single-nature are called Monophysites.What happened between Cyril & Nestorius is this . . .Nestorius was an elder and head of a monastery in Antioch when the emperor Theodosius II chose him to be Bishop of Constantinople in 428.Now, what I’m about to say some will find hard to swallow, but while Nestorius’s name became associated with one of the major heresies to split the church, the error he’s accused of he most likely wasn’t guilty of. What Nestorius was guilty of was being a jerk. His story is typical for several of the men who were picked to lead the church at Constantinople during the 4th through 7th Cs; effective preachers but lousy administrators & seriously lacking in people skills. Look, if you’re going to be pegged to lead the Church at the Political center of the Empire, you better be a savvy political operator, as well as a man of moral & ethical excellence. A heavy dose of tact ought to have been a pre-requisite. But guys kept getting selected who came to the Capital on a campaign to clean house. And many of them seem to have thought subtlety was the devil’s tool.As soon as Nestorius arrived in Constantinople, he started a harsh campaign against heretics, meaning anyone with whom he disagreed. It wouldn’t take long before his enemies accused him of the very thing he accused others of. But in their case, their accusations were born of jealousy.Where they deiced to take offense was when Nestorius balked at the use of the word Theotokos. The word means God-bearer, and was used by the church at Alexandria for the mother of Jesus. While the Alexandrians said they rejected Apollinarianism, they, in fact, emphasized the divine nature of Jesus, saying it overwhelmed His human nature. The Alexandrian bishop, Cyril, was once again jealous of the Antiochan Nestorius’ selection as bishop for the Capital. As his uncle Theophilus had taken advantage of Chrysostom’s disfavor to get him deposed, Cyril laid plans for removing the tactless & increasingly unpopular Nestorius. The battle over the word Theotokos became the flashpoint of controversy, the crack Cyril needed to pry Nestorius from his position.To supporters of the Alexandrian theology, Theotokos seemed entirely appropriate for Mary. They said she DID bear God when Jesus took flesh in her womb. And to deny it was to deny the deity of Christ!Nestorius and his many supporters were concerned the title “Theotokos” made Mary a goddess. Nestorius maintained that Mary was the mother of the man Who was united with the divine Logos, and nothing should be said that might imply she was the “Mother à of God.” Nestorius preferred the title Christokos; Mary was the Christ-bearer. But he lacked a vocabulary and the theological sophistication to relate the divine and human natures of Jesus in a convincing way.Cyril, on the other hand, argued convincingly for his position from the Scriptures. In 429, Cyril defended the term Theotokos. His key text was John 1: 14, “The Word became flesh.” I’d love to launch into a detailed description of the nuanced debate between Cyril and Nestorius over the nature of Christ but it would leave most, including myself, no more clued in than we are now.Suffice it to say, Nestorius maintained the dual-nature-in-the-one-person of Christ while Cyril stuck to the traditional Alexandrian line and said while Jesus was technically 2 natures, human & divine, the divine overwhelmed the human so that He effectively operated as God in a physical body.Where this came down to a heated debate was over the question of whether or not Jesus really suffered in His passion. Nestorius said that the MAN Jesus suffered but not His divine nature, while Cyril said the divine nature did indeed suffer.When the Roman Bishop Celestine learned of the dispute between Cyril and Nestorius, he selected a churchman named John Cassian to respond to Nestorius. He did so in his work titled On the Incarnation in 430. Cassian sided with Cyril but wanted to bring Nestorius back into harmony. Setting aside Cassian’s hope to bring Nestorius into his conception of orthodoxy, Celestine entered a union with Cyril against Nestorius and the church at Antioch he’d come from. A synod at Rome in 430 condemned Nestorius, and Celestine asked Cyril to conduct proceedings against him.Cyril condemned Nestorius at a Synod in Alexandria and sent him a notice with a cover letter listing 12 anathemas against Nestorius and anyone else who disagreed with the Alexandrian position. For example à “If anyone does not confess Emmanuel to be very God, and does not acknowledge the Holy Virgin to be Theotokos, for she brought forth after the flesh the Word of God become flesh, let him be anathema.”Receiving the letter from Cyril, Nestorius humbly resigned and left for a quiet retirement at Leisure Village in Illyrium. à Uh, not quite. True to form, Nestorius ignored the Synod’s verdict.Emperor Theodosius II called a general council to meet at Ephesus in 431. This Council is sometimes called the Robber’s Synod because it turned into a bloody romp by Cyril’s supporters. As the bishops gathered in Ephesus, it quickly became evident the Council was far more concerned with politics than theology. This wasn’t going to be a sedate debate over texts, words & grammar. It was going to be a physical contest. Let’s settle doctrinal disputes with clubs instead of books.Cyril and his posse of club-wielding Egyptian monks, and I use the word posse purposefully, had the support of the Ephesian bishop, Memnon, along with the majority of the bishops from Asia. The council began on June 22, 431, with 153 bishops present. 40 more later gave their assent to the findings. Cyril presided. Nestorius was ordered to attend but knew it was a rigged affair and refused to show. He was deposed and excommunicated. Ephesus rejoiced.On June 26, John, bishop of Antioch, along with the Syrian bishops, all of whom had been delayed, finally arrived. John held a rival council consisting of 43 bishops and the Emperor’s representative. They dec

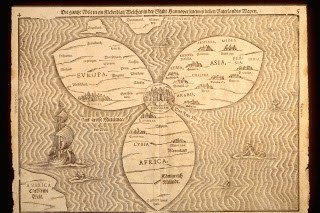

This episode of Communio Santorum is titled, “And In the East – Part 1.”The 5th C Church Father Jerome wrote, “[Jesus] was present in all places with Thomas in India, with Peter in Rome, with Paul in Illyria, with Titus in Crete, with Andrew in Greece, with each apostle . . . in his own separate region.”So far we’ve been following the track of most western studies of history, both secular & religious, by concentrating on what took place in the West & Roman Empire. Even though we’ve delved briefly into the Eastern Roman Empire, as Lars Brownworth aptly reminds us in his outstanding podcast, 12 Byzantine Emperors, even after the West fell in the 5th Century, the Eastern Empire continued to think of & call itself Roman. It’s later historians who refer to it as the Byzantine Empire.Recently we’ve seen the focus of attention shift to the East with the Christological controversies of the 4th & 5th Cs. In this episode, we’ll stay in the East and follow the track of the expansion of the Faith as it moved Eastward. This is an amazing chapter often neglected in traditional treatments of church history. It’s well captured by Philip Jenkins in his book, The Lost History of Christianity.We start all the way back at the beginning with the apostle Thomas. He’s linked by pretty solid tradition to the spread of Christianity into the East. In the quote we started with from the early 5th C Church Father Jerome, we learn that the Apostle Thomas carried the Gospel East all the way to India.In the early 4th C, Eusebius also attributed the expansion of the faith in India to Thomas. Though these traditions do face some dispute, there are still so-called ‘Thomas Christians’ in the southern Indian state of Kerala today. They use an Aramaic form of worship that had to have been transported there very early. A tomb & shrine in honor of Thomas at Mylapore is built of bricks used by a Roman trading colony but was abandoned after ad 50. There’s abundant evidence of several Roman trading colonies along the coast of India, with hundreds of 1st C coins & ample evidence of Jewish communities. Jews were known to be a significant part of Roman trade ventures. Their communities were prime stopping places for the efforts of Christian missionaries as they followed the Apostle Paul’s model as described in the Book of Acts.A song commemorating Thomas’ role in bringing the faith to India, wasn’t committed to writing till 1601 but was said to have been passed on in Kerala for 50 generations. Many trading vessels sailed to India in the 1st C when the secret of the monsoon winds was finally discovered, so it’s quite possible Thomas did indeed make the journey. Once the monsoons were finally figured out, over 100 trade ships a year crossed from the Red Sea to India.Jesus told the disciples to take the Gospel to the ends of the Earth. While they were slow to catch on to the need to leave Jerusalem, persecution eventually convinced them to get moving. It’s not hard to imagine Thomas considering a voyage to India as a way to literally fulfill the command of Christ. India would have seemed the end of the Earth.Thomas’s work in India began in the northwest region of the country. A 4th C work called The Acts of Thomas says that he led a ruler there named Gundafor to faith. That story was rejected by most scholars & critics until an inscription was discovered in 1890 along with some coins which verify the 20-year reign in the 1st C of a King Gundafor.After planting the church in the North, Thomas traveled by ship to the Malabar Coast in the South. He planted several churches, mainly along the Periyar River. He preached to all classes of people and had about 17,000 converts from all Indian castes. Stone crosses were erected at the places where churches were founded, and they became centers for pilgrimages. Thomas was careful to appoint local leadership for the churches he founded.He then traveled overland to the Southeast Indian coast & the area around Madras. Another local king and many of his subjects were converted. But the Brahmins, highest of the Indian castes, were concerned the Gospel would undermine a cultural system that was to their advantage, so they convinced the king at Mylapore, to arrest & interrogate him. Thomas was sentenced to death & executed in AD 72. The church in that area then came under persecution and many Christians fled for refuge to Kerala.A hundred years later, according to both Eusebius & Jerome, a theologian from the great school at Alexandria named Pantaenus, traveled to India to “preach Christ to the Brahmins.”[1]Serving to confirm Thomas’ work in India is the writing of Bar-Daisan. At the opening of the 3rd Century, he spoke of entire tribes following Jesus in North India who claimed to have been converted by Thomas. They had numerous books and relics to prove it. By AD 226 there were bishops of the Church in the East in northwest India, Afghanistan & Baluchistan, with thousands of laymen and clergy engaging in missionary activity. Such a well-established Christian community means the presence of the Faith there for the previous several decades at the least.The first church historian, Eusebius of Caesarea, to whom we owe so much of our information about the early Church, attributed to Thomas the spread of the Gospel to the East. As those familiar with the history of the Roman Empire know, the Romans faced continuous grief in the East by one Persian group after another. Their contest with the Parthians & Sassanids is a thing of legend. The buffer zone between the Romans & Persians was called Osrhoene with its capital city of Edessa, located at the border of what today is northern Syria & eastern Turkey. According to Eusebius, Thomas received a request from Abgar, king of Edessa, for healing & responded by sending Thaddaeus, one of the disciples mentioned in Luke 10.[2] Thus, the Gospel took root there. There was a sizeable Jewish community in Edessa from which the Gospel made several converts. Word got back to Israel of the Church community growing in the city & when persecution broke out in the Roman Empire, many refugees made their way East to settle in a place that welcomed them.Edessa became a center of the Syrian-speaking church which began sending missionaries East into Mesopotamia, North into Persia, Central Asia, then even further eastward. The missionary Mari managed to plant a church in the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, which became a center of missionary outreach in its own right.By the late 2nd C, Christianity had spread throughout Media, Persia, Parthia, and Bactria. The 2 dozen bishops who oversaw the region carried out their ministry more as itinerant missionaries than by staying in a single city and church. They were what we refer to as tent-makers; earning their way as merchants & craftsmen as they shared the Faith where ever they went.By AD 280 the churches of Mesopotamia & Persia adopted the title of “Catholic” to acknowledge their unity with the Western church during the last days of persecution by the Roman Emperors. In 424 the Mesopotamian church held a council at the city of Ctesiphon where they elected their first lead bishop to have jurisdiction over the whole Church of the East, including India & Ceylon, known today as Sri Lanka. Ctesiphon was an important point on the East-West trade routes which extended to India, China, Java, & Japan.The shift of ecclesiastical authority was away from Edessa, which in 216 became a tributary of Rome. The establishment of an independent patriarchate contributed to a more favorable attitude by the Persians, who no longer had to fear an alliance with the hated Romans.To the west of Persia was the ancient kingdom of Armenia, which had been a political football between the Persians & Romans for generations. Both the Persians & Romans used Armenia as a place to try out new diplomatic maneuvers with each other. The poor Armenians just wanted to be left alone, but that was not to be, given their location between the two empires. Armenia has the historical distinction of being the first state to embrace Christianity as a national religion, even before the conversion of Constantine the Great in the early 4th C.The one who brought the Gospel to Armenia was a member of the royal family named Gregory, called “the Illuminator.” While still a boy, Gregory’s family was exiled from Armenia to Cappadocia when his father was thought to have been part of a plot to assassinate the King. As a grown man who’d become a Christian, Gregory returned to Armenia where he shared the Faith with King Tiridates who ruled at the dawn of the 4th C. Tiridates was converted & Gregory’s son succeeded him as bishop of the new Armenian church. This son attended the Council of Nicea in 325. Armenian Christianity has remained a distinctive and important brand of the Faith, with 5 million still professing allegiance to the Armenian Church.[3]Though persecution came to an official end in the Roman Empire with Constantine’s Edict of Toleration in 313, it BEGAN for the church in Persia in 340. The primary cause for persecution was political. When Rome became Christian, its old enemy turned anti-Christian. Up to that point, the situation had been reversed. For the first 300 hundred years, it was in the West Christians were persecuted & Persia was a refuge. The Parthians were religiously tolerant while their less tolerant Sassanid successors were too busy fighting Rome to waste time or effort on the Christians among them.But in 315 a letter from Constantine to his Persian counterpart Shapur II triggered the beginnings of an ominous change in the Persian attitude toward Christians. Constantine believed he was writing to help his fellow believers in Persia but succeeded only in exposing them. He wrote to the young Persian ruler: “I rejoice to hear that the fairest provinces of Persia are adorned with Christians. Since you are so powerful and pious, I commend them to your care, and leave them in your protection.”Th

This episode of Communio Santorum is titled, “And In the East – Part 2.”In our last episode, we took a brief look at the Apostle Thomas’ mission to India. Then we considered the spread of the faith into Persia. Further study of the Church in the East has to return to the Council of Chalcedon in the 5th C where Bishop Nestorius was condemned as a heretic.As we’ve seen, the debate about the deity of Christ central to the Council of Nicea in 325, declared Jesus was of the same substance as the Father. It took another hundred years before the deity-denying error of Arianism was finally quashed. But even among orthodox & catholic, Nicean-holding believers, the question was over how to understand the nature of Christ. He’s God – got it! But he’s also human. How are we to understand His dual-nature. It was at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 that issue was finally decided. And the Church of the East was deemed to hold a position that was unorthodox.The debate was sophisticated & complex, and not a small part decided more by politics than by concern for theological purity. The loser in the debate was Bishops Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople. To make a complex issue simple, those who emphasized the unity of the 2 natures came to be called the Monophysites = meaning a single nature. They regarded Nestorius as a heretic because he emphasized the 2 natures as distinct; even to the point of saying Nestorius claimed Jesus was 2 PERSONS. That’s NOT what Nestorius said, but it’s what his opponents managed to get all but his closest supporters to believe he said. In fact, when the Council finally issued their creedal statement, Nestorius claimed they only articulated what he’d always taught. Even though the Council of Chalcedon declared Nestorianism heretical, the Church of the East continued to hold on to their view in the dual nature of Christ, in opposition to what they considered the aberrant view of monophysitism.By the dawn of the 6th C, there were 3 main branches of the Christian church:The Church of the West, which looked to Rome & Constantinople for leadership.The Church of Africa, with its great center at Alexandria & an emerging center in Ethiopia;And the Church of the East, with its center in Persia.As we saw last episode, the Church of the East was launched from Edessa at the border between Northern Syria & Eastern Turkey. The theological school there transferred to Nisibis in Eastern Turkey in 471. It was led by the brilliant theologian Narsai. This school had a thousand students who went out from there to lead the churches of the East. Several missionary endeavors were also launched from Nisibis – just as Iona was a sending base for Celtic Christianity in the far northwest. The Eastern Church mounted successful missions among the nomadic people of the Middle East & Central Asia between the mid-5th thru 7th Cs. These included church-planting efforts among the Huns. Abraham of Kaskar who lived during the 6th C did much to plant monastic communities throughout the East.During the first 1200 years, the Church of the East grew both geographically & numerically far more than in the West. The primary reason for this is because in the East, missionary work was largely a movement of the laity. As Europe moved into the Middle Ages with its strict feudal system, travel ground to a standstill, while in the East, trade & commerce grew. This resulted in the movement of increasing numbers of people who carried the Faith with them.Another reason the Church in the East grew was persecution. As we saw last time, before Constantine, the persecutions of the Roman Empire pushed large numbers of believers East. Then, when the Sassanids began the Great Persecution of Christians in Persia, that pushed large numbers of the Faithful south & further East. Following the persecution that came under Shapur II, another far more severe round of persecution broke out in the mid-5th C that saw 10 bishops and 153,000 Christians massacred within a few days.When we think of Arabia, many immediately think of Islam. But Christianity had taken root in the peninsula long before Muhammad came on the scene. In fact, a bishop from Qatar was present at the Council of Nicea in 325! The Arabian Queen Mawwiyya, whose forces defeated the Romans in 373, insisted on receiving an orthodox bishop before she would make peace. There was mission-outreach to the south-eastern region of Arabia, in what is today Yemen before the birth of Muhammad by both Nestorian & Monophysite missionaries. By the opening of the 6th C, there were dozens of churches all along the Arabian shore of the Persian Gulf.The rise of Islam in the 7th C was to have far-reaching consequences for the Church in the East. The Persian capital at Ctesiphon fell to the Arabs in 637. Since the Church there had become a kind of Rome to the Church of the East, the impact was massive. Muslims were sometimes tolerant of religious minorities but only as communities of the disenfranchised known as dhimmi. They became ghettoes stripped of their vitality. At the same time, the Church of the East was being shredded by Muslim conquests, it was taking one of its biggest steps forward by reaching into China in the mid 7th C.While the Church of the West grew mostly by the work of trained clergy & the missionary monks of Celtic Christianity, in the East, as often as not, it was Christian merchants & craftsmen who advanced the Faith. The Church of the East placed great emphasis on education and literacy. It was generally understood being a follower of Jesus meant an education that included reading, writing & theology. An educated laity meant an abundance of workers capable of spreading the faith – & spread it they did! Christians often found employment among less advanced people, serving in government offices, & as teachers & secretaries. They helped solve the problem of illiteracy by inventing simplified alphabets based on the Syriac language which framed their own literature & theology.While that was at first a boon, in the end, it proved a hindrance. Those early missionaries failed to understand the principle of contextualization; that the Gospel is super-cultural; it transcends things like language & traditions. Those early missionaries who pressed rapidly into the East assumed that their Syrian-version of the Faith was the ONLY version & tried to convert those they met to that. As a consequence, while a few did accept the faith & learned Syrian-Aramaic, a few generations later, the old religions & languages reasserted themselves and Christianity was either swept away or so assimilated into the culture that it wasn’t really Biblical Christianity any longer.The golden age of early missions in Central Asia was from the end of the 4th C to the latter part of the 9th. Then both Islam & Buddhism came onto the scene.Northeast of Persia, the Church had an early & extensive spread around the Oxus River. By the early 4th C the cities of Merv, Herat & Samarkand had bishops.Once the Faith was established in this region, it spread quickly further east into the basin of the Tarim River, then into the area north of the Tien Shan Mountains & Tibet. It spread along this path because that was the premier caravan route. With so many Christians engaged in trade, it was natural the Gospel was soon planted in the caravan centers.In the 11th C the Faith began to spread among the nomadic peoples of the central Asian regions. These Christians were mostly from the Tartars & Mongol tribes of Keraits, Onguts, Uyghurs, Naimans, and Merkits.It’s not clear exactly when Christianity reached Tibet, but it most likely arrived there by the 6th C. The territory of the ancient Tibetans stretched farther west & north than the present-day nation, & they had extensive contact with the nomadic tribes of Central Asia. A vibrant church existed in Tibet by the 8th C. The patriarch of the Assyrian Church in Mesopotamia, Timothy I, wrote from Baghdad in 782 that the Christian community in Tibet was one of the largest groups under his oversight. He appointed a Tibetan patriarch to oversee the many churches there. The center of the Tibetan church was located at Lhasa and the Church thrived there until the late 13th C when Buddhism swept through the region.An inscription carved into a large boulder at the entrance to the pass at Tangtse, once part of Tibet but now in India, has 3 crosses with some writing indicating the presence of the Christian Faith. The pass was one of the main ancient trade routes between Lhasa and Bactria. The crosses are stylistically from the Church of the East, and one of the words appears to be “Jesus.” Another inscription reads, “In the year 210 came Nosfarn from Samarkand as an emissary to the Khan of Tibet.” That might not seem like a reference to Christianity until you take a closer look at the date. 210! That only makes sense in reference to measuring time since the birth of Christ, which was already a practice in the Church.The aforementioned Timothy I became Patriarch of the Assyrian church about 780. His church was located in the ancient Mesopotamian city of Seleucia, the larger twin to the Persian capital of Ctesiphon. He was 52 & well past the average life expectancy for people of the time. Timothy lived into his 90’s, dying in 823. During his long life, he devoted himself to spiritual conquest as energetically as Alexander the Great had to the military kind. While Alexander built an earthly empire, Timothy sought to expand the Kingdom of God.At every point, Timothy’s career smashes everything we think we know about the history of Christianity at that time. He alters ideas about the geographical spread of the Faith, its relationship with political power, its cultural influence, & its interaction with other religions. In terms of his prestige & the geographical extent of his authority, Timothy was the most significant Christian leader of his day; far more influential than the pope in Rome or the patriarch in Constantin

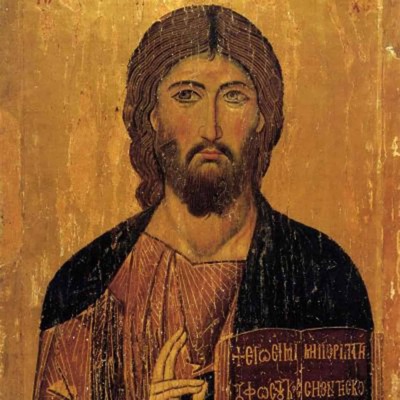

This Episode of CS is titled, “Orthodoxy, with an Eastern Flavor.”We need to begin this episode by defining the term “Orthodoxy.”It comes from Greek. Orthos means “straight” & idiomatically means that which is right or true. Doxa is from the verb dokein = to think; doxa is one’s opinion or belief.As it’s most often used, orthodoxy means adherence to accepted norms. In reference to Christianity, it means conforming to the creeds of the early Church; those statements of faith issued by the church councils we’ve looked at in recent podcasts and we have a series on in Season 2.In opposition to orthodoxy is what’s called heterodoxy; other-teaching. Heterodoxy deviates from the Faith defined by the Creeds. Specific instances of heterodoxy, that is - deviant doctrines are called heresy; with those who hold them known as heretics. When heresy causes a group of people to remove themselves from the Communion of Saints so they can form their own distinct community, it’s called a Schism.But there’s another, very different way the word Orthodox is used in Christianity. It’s the name of one of the 4 great branches of the Church; Roman Catholic, Protestant, & Eastern Orthodox. The fourth is that branch of the Faith we’ve been looking at for the last couple episodes – The Nestorian Church, AKA The Church of the East.In the West, we’re familiar with Roman Catholicism & Protestantism. We’re less aware of Eastern Orthodoxy and most people haven’t even heard of the Nestorian Church. Ignorance of Eastern Orthodoxy is tragic considering the Byzantine Empire which was home to the Orthodox Church continued to embody the values & traditions of the Roman Empire until the mid-15th C, a full millennium after the Fall of Rome in AD 476.It’ll be many episodes of CS before we get to the year 1054 when the Great Schism took place between the Eastern & Western churches. But I think it helpful to understand how Eastern Orthodoxy differs from Roman Catholicism so we can stay a little closer to the narrative timeline of how the Church developed in upcoming episodes.One of the ways we can better understand the Eastern Orthodox Church is to quickly summarize the history of Roman Catholicism in Europe during the Middle Ages as a contrast.In the West, the Church, led by the Pope with cardinals & bishops, oversaw the spiritual & religious aspects of European culture. The affiliation between church & state that began with Constantine the Great & continued for the next century & a half was at best a tense arrangement. Sometimes the Pope & Emperor were close; at other times they were at odds & competed for power. Overall, it was an uneasy marriage of the secular & religious. During the Middle Ages, the Church exerted tremendous influence in the secular sphere, & civil rulers either sought to ally themselves with the church, or to break the Church’s grip on power. Realizing how firm that grip was, some civil rulers even sought to infiltrate the ranks of the church to install their own bishops & popes. The Church played the same game & kept spies in many of Europe’s courts. These agents reported to Rome & sought to influence political decisions.The situation was dramatically different in the East where the church & state worked in harmony. Though foreign to the Western Mind, & especially the Modern Western Mind which considers a great barrier between Church & State, in the ancient Byzantine Empire, Church & State were partners in governance. They weren’t equivalent, but they worked together to shape policies & provide leadership that allowed the Eastern Empire to not only resist the forces that saw the West collapse, but to maintain the Empire until the 15th C when it was finally over-run by the Ottoman Turks.In our attempt to understand Eastern Orthodoxy, we’ll look to the description Marshall Shelly provides in his excellent book, Church History in Plain Language.The prime starting point for understanding Orthodoxy isn’t to examine its basic doctrines but rather its use of holy images called icons. Icons are highly stylized portrayals of one or more saints, set against a golden background and a halo around the head. Icons are crucial in understanding Eastern Orthodoxy. Orthodox believers enter their church and go first to a wall covered with icons called the iconostasis. This wall separates the sanctuary from the nave. The worshipper kisses the icons before taking his/her place in the congregation. A visitor to an Orthodox home will find an icon in the east corner of the main room. If the guest is him/herself Orthodox, they’ll greet the icon by crossing themselves & bowing. Only then will they greet the host.To the Orthodox, icons are much more than man-made images. They’re manifestations of a divine ideal. They’re considered a window into heaven. In the same way grace is thought to be imparted through the Roman Catholic Mass, grace is thought to flow from heaven to earth thru icons. Protestants can better understand the importance of icons to the Orthodox by considering how important The Bible is to them. As Scripture is the written revelation of God’s will & truth, so icons are considered as visual representations of truth that have as much if not more to impart by way of revelation to believers. In fact, icons aren’t painted, they are said to be “written,” conveying the idea that they fulfill the same role as Scripture. The Bible is the Scripture in words; icons are scripture in images.As I said, an icon is a highly stylized portrayal of saints or Bible scenes on panels, usually made of wood, most often cypress which has been prepped with cloth & gesso. The background is gold leaf, depicting the glory of the divine realm the image is thought to come from, with bright tempura paint making the figures & decoration. When dry, the panel is covered in varnish. Some ancient icons are amazing pieces of art. Icon artists consider the writing of icons as a spiritual act & prepare by fasting & prayer, after having completed laborious technical training.Strictly speaking, Eastern Orthodox theology says icons are not objects of devotion themselves. They’re thought to be windows into the spiritual realm by which the divine is able to infiltrate & effect the physical. Though that’s the official doctrinal position on icons, they are kissed & venerated at the beginning & at various points during a service. Icons aren’t worshipped, they’re venerated; meaning while they aren’t given the worship due God alone, they are esteemed as a medium by which grace is bestowed on worshippers. While this is the technical explanation for the use of icons, watching how worshipers use them and listening to how highly they’re regarded, I’m hard-pressed to see how in a practical sense, there’s any difference between veneration & worship. To many objective observers, the use of icons seems a clear violation of the Second Commandment prohibiting the use of images in the worship of God.Scholars debate when Eastern Christians began to use icons. Some say their use began in the late 6th or 7th C. Before icons became popular, relics played an important part of church life. Body parts of saints as well as items connected to Biblical stories were thought to possess spiritual power.Caution: I know opine à All of this was superstitious silliness, but it framed the thinking of many. Since there were only so many holy relics to go around and each church made claim to one to draw worshippers in, icons began to be used as surrogates for relics. If you can’t have a piece of the cross, maybe a golden painting of Mary holding the baby Jesus would do the trick. If you can’t have Stephen’s index finger, how about his icon? Miraculous stories hovering round relics & icons were legion, each claiming some special connection to God & saints. Relics were said to bring healing. Icons were said to weep tears or bleed. The fragrant scent of incense was said to attend many of the greatest icons. The tales go on & on.The question in all these claims is; where do we find the use of such things in Scripture? By way of reminder, Evangelical Christians determine what defines Biblical as opposed to Eastern Orthodoxy by this set of questions –1) Did Jesus teach or model in in the Gospels?

2) Did the Early Church practice it in the book of Acts?

3) Do the NT epistles comment on or regulate it as normative for faith & practice?Using this 3-fold filter, the use of relics & icons isn’t orthodox.The Eastern Orthodox church refers to itself as the Church of the 7 Councils. It claims a superior form of the Christian Faith because it draws its doctrine from what it says are the main Church Councils that defined normal Christian belief. The last Council, Nicaea II in AD 787, came about as a response to the Iconoclast Controversy which we’ll talk about later. The point here is that Nicaea II declared the veneration of icons to be good & proper. What we’re to glean from this is that claiming to be a church that adheres to the creeds of the 7 Councils doesn’t mean much if those councils were just gatherings of men. It isn’t their Creeds that are important & that define the Faith; It’s Scripture alone that has that role. Creedal statements are only so good in as much as they are proper interpretations of the Word of God. But they are not themselves, that Word.Another important distinction between the Eastern & Western Church is how they view the object of salvation.Western Christians tend to understand the relationship between God & man in legal terms. Man is obliged to meet the demands of a just God. Sin, sacrifice, & salvation are all aspects of divine justice. Salvation is cast primarily in terms of justification.In Roman Catholicism, when a believer sins, a priest determines what payment or penance he owes to God. If he’s unable to provide enough penance for some especially heinous sin, then purgatory in the afterlife provides a place where his soul can be expiated.In Protestantism, penance & purgatory are set aside for t

This week’s episode of Communion Sanctorum is titled – “Justinian Sayin’”During the 5th C, while the Western Roman Empire was falling to the Goths, the Eastern Empire centered at Constantinople looked like it would carry on for centuries. Though it identified itself as Roman, historians refer to the Eastern region as the Byzantine Empire & Era. It gets that title from Byzantium, the city’s name before Constantine made it his new capital.During the 5th C, the entire empire, both East & West went into decline. But in the 6th Century, the Emperor Justinian I lead a major revival of Roman civilization. Reigning for nearly 40 years, Justinian not only brought about a re-flowering of culture in the East, he attempted to reassert control over those lands in the West that had fallen to barbarian control.A diverse picture of Justinian the Great has emerged. For years the standard way to see him was as an intelligent, ambitious, energetic, gregarious leader plagued by an unhealthy dose of vanity. Dare I say it? Why not: He wanted to make Rome Great Again. While that’s been the traditional way of understanding Justinian, more recently, that image has been edited slightly by giving his wife and queen Theodora, a more prominent role in fueling his ambition. Whatever else we might say about this husband and wife team, they were certainly devout in their faith.Justinian's reign was bolstered by the careers of several capable generals who were able to translate his desire to retake the West into reality. The most famous of these generals was Belisarius, a military genius on par with Hannibal, Caesar, & Alexander. During Justinian's reign, portions of Italy, North Africa & Spain were reconquered & put under Byzantine rule.The Western emperors in Rome's long history tended to be more austere in the demonstrations of their authority by keeping their wardrobe simple & the customs related to their rule modest, as befitted the idea of the Augustus as Princeps = meaning 1st Citizen. Eastern emperors went the other way & eschewed humility in favor of an Oriental, or what we might call “Persian” model of majesty. It began with Constantine who broke with the long-held western tradition of Imperial modesty & arrayed himself as a glorious Eastern Monarch. Following Constantine, Eastern emperors wore elaborate robes, crowns, & festooned their courts with ostentatious symbols of wealth & power. Encouraged by Theodora, Justinian advanced this movement and made his court a grand showcase. When people appeared before the Emperor, they had to prostrate themselves, as though bowing before a god. The pomp and ceremony of Justinian’s court were quickly duplicated by the church at Constantinople because of the close tie between church & state in the East.It was this ambition for glory that moved Justinian to embark on a massive building campaign. He commissioned the construction of entire towns, roads, bridges, baths, palaces, & a host of churches & monasteries. His enduring legacy was the Church of the Holy Wisdom, or Cathedral of St. Sophia, the main church of Constantinople. The Hagia Sofia was the epitome of a new style of architecture centered on the dome, the largest to be built to that time. Visitors to the church would stand for hours in awe staring up at the dome, incredulous that such a span could be built by man. Though the rich interior façade of the church has been gutted by years of conflict, the basic structure stands to this day as one of Istanbul’s premier attractions.Justinian was no mean theologian in his own right. As Emperor he wanted to unite the Church under one creed and worked hard to resolve the major dispute of the day; the divide between the Orthodox faith as expressed in the Council of Chalcedon & the Monophysites.By way of review; the Monophysites followed the teachings of Cyril of Alexandria who'd contended with Nestorius over the nature of Christ. Nestorius emphasized the human nature of Jesus, while Cyril emphasized Jesus’ deity. The followers of both took their doctrines too far so that the Nestorians who went East into Persia tended to diminish the deity of Christ, while the Cyrillians who went south into Egypt, elevated Jesus’ deity at the expense of his humanity. They put such an emphasis on his deity they became Monophysites; meaning 1 nature-ites.Justinian tried to reconcile the Orthodox faith centered at Constantinople with the Monophysites based in Egypt by finessing the words used to describe the faith. Even though the Council of Chalcedon had officially ended the dispute, there was still a rift between the Church at Constantinople and that in Egypt.Justinian tried to clarify how to understand the natures of Jesus as God & Human. Did He have 1 nature or 2? And if 2. How did those 2 natures co-exist in the Son of God? Were they separate & distinct or merged into something new? If they were distinct, was one superior to the other? This was the crux of the debate the Council of Chalcedon had struggled with and which both Cyril & Nestorius contended over.Justinian had partial success in getting moderate Monophysites to agree with his theology. He was helped by the work of a monk named Leo of Byzantium. Leo proposed that in Christ, his 2 natures were so co-mingled & united so that they formed one nature, he identified as the Logos.In 544 Emperor Justinian issued an edict condemning some pro-Nestorian writings. Many Western bishops thought the edict a scandalous refutation of the Chalcedonian Creed. They assumed Justinian had come out as a Monophysite. Pope Vigilius condemned the edict and broke off fellowship with the Patriarch of Constantinople because he supported the Emperor’s edict. Shortly thereafter, when Pope Vigilius visited Constantinople, he did an abrupt about-face, adding his own censure to the condemned pro-Nestorian writings. Then in 550, after several bishops criticized this reversal, Vigilius did another & said the writings weren’t prohibited after all.Nothing like being a stalwart pillar of an unwavering stand. Vigilius was consistent; he consistently wavered when under pressure.All of this created so much controversy that in 553 Justinian called the 5th Ecumenical Council at Constantinople. Though it was supposed to be a counsel of the whole church, Pope Vigilius refused to attend. At Justinian's demand, the Council affirmed his original edict of 544, further condemning anyone who supported the pro-Nestorian writings. The Emperor banished Vigilius for his refusal to attend, saying he would be reinstated only on condition of his accepting the Council's decision.Guess what Vigilius did. Yep. He relented and endorsed the Council's finding. So the result was that the Chalcedonian Creed was reinterpreted along far more Monophysite lines. Jesus’ deity was elevated to the foreground while his humanity was relegated to a distant backwater. This became the official position of the Eastern Orthodox Church.But Justinian's desire to bring unity wasn't achieved. The Western bishops refused to recognize the Council of Constantinople's interpretation of the Chalcedon Creed. And while the new spin on Jesus’ nature was embraced in the East, the hard-core Monophysites of Egypt stood their ground. They’d come to hold their theology with a fierce regional loyalty. To accept Justinian's formulation was deemed a compromise they saw not only as heretical but as unpatriotic. They vehemently refused to come under the control of Constantinople.What Justinian was unable to do by theological compromise and diplomacy, he attempted, by force. After all, as they say, a War is just diplomacy by other means. And as Justinian might say, “What good is it being King if you can’t bash heads whenever you want?”The Emperor also sought to eradicate the last vestiges of paganism throughout the Empire. He commanded both civil officials & church leaders to seek out all pagan cultic practices and pre-Christian Greek philosophy and bring an immediate end to them. He closed the schools of Athens, the last institutions teaching Greek philosophy. He allowed the Jews to continue their faith but sought to regulate their practices. He decreed the death penalty for Manichaeans and other heretics like the Montanists. When his harsh policies stirred up rebellion, he was ruthless in putting it down.Toward the end of his reign, his wife Theodora’s Monophysite beliefs influenced him to move further in that direction. He sought to recast the 5th Council's findings into a new form that would gain greater Monophysite support. This new view has been given the tongue-twisting label of Aph-thar-to-docetism.According to this view, even Jesus' physical body was divine so that from conception to death, it didn’t change. This means Jesus didn’t suffer or know the desires & passions of mortals.When he tried to impose this doctrine on the Church, the vast majority of bishops refused to comply. So Justinian made plans to enforce compliance but died before the campaign could begin, much to the relief of said bishops.Justinian took an active hand in ordering the Church in more than just theology. He passed laws dealing with various aspects of church life. He appointed bishops, assigned abbots to monasteries, ordained priests, managed church lands and oversaw the conduct of the clergy. He forbade the practice of simony; the sale of church offices. Being a church official could be quite lucrative, so the practice of simony was frequently a problem.The Emperor also forbade the clergy from attending chariot races and the theater. This seems harsh if we think of these as mere sporting and cultural events. They weren't. Both events were more often than not scenes of moral debauchery where ribald behavior was common. One did not attend a race for polite or dignified company. The races were à well, racy. And the theater was a place where perversions were enacted onstage. That Justinian forbade clergy from attending these events means had been common for them to do