Discover ICRC Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog

ICRC Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog

ICRC Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog

Author: ICRC Law and Policy

Subscribed: 121Played: 2,976Subscribe

Share

© All rights reserved

Description

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Humanitarian Law & Policy blog is a unique space for timely analysis and debate on international humanitarian law (IHL) issues and the policies that shape humanitarian action.

279 Episodes

Reverse

More than seven decades after their adoption, the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 remain foundational to contemporary international humanitarian law (IHL). Efforts to update their Commentaries testify to both the resilience of the Geneva Conventions and their enduring relevance in modern armed conflicts. Yet the story of their making is inseparable from the longer history of the law of armed conflict, which developed in the late nineteenth century within a deeply hierarchical international legal order. From the perspective of colonized states and territories, that history reveals a persistent divide between European and non-European worlds, a divide that shaped not only general international law but also key features of the Geneva Conventions themselves.

In this post, part of a joint symposium on the updated Commentary on the Fourth Geneva Convention with EJIL:Talk! and Just Security, Associate Professor Srinivas Burra revisits the adoption of the 1949 Geneva Conventions against the backdrop of the Second World War, the creation of the United Nations, and the onset of decolonization. Focusing on the Fourth Convention’s regime of occupation and on Common Article 3, he examines these developments from a Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) perspective, accounting for the structural legacies of empire in international law. He argues that while these provisions marked important advances, they also carried forward earlier exclusions embedded in colonial conceptions of sovereignty. Read in this light, the Conventions represent both a decisive break in humanitarian protection and a continuation of hierarchies inherited from the nineteenth century.

Islamic legal traditions and the modern framework of international humanitarian law (IHL) emerged from different contexts and traditions, but they share many underlying values – such as restraint, humanity, and the protection of those not (or no longer) participating in hostilities. Islamic law therefore offers a distinct but complementary perspective to IHL on the sanctity of life (ḥurmat al-nafs), particularly in contexts where international legal frameworks lack traction, understanding, or perceived legitimacy.

In this post, and as part of our Emerging Voices series, legal researcher Alannah Travers explores how Islamic law, as its own coherent and longstanding legal tradition, offers a parallel framework of moral constraint during armed conflict. She argues that better understanding these Islamic legal norms can provide stronger grounds for compliance with protective norms, deepening our collective understanding of the right to life in war.

The updated ICRC Commentary on the Fourth Geneva Convention (GC IV) includes a number of important updates to its treatment of Common Article 3 (CA3). These relate primarily to three areas: the treatment of coalitions in non-international armed conflict (NIAC); the provision of support by one party to another; and questions of gender and the treatment of other marginalized groups.

In this post – part of a joint blog symposium on the updated GC IV Commentary with EJIL: Talk! and Just Security – Associate Professor Katharine Fortin examines these developments, highlighting their significance and strengths while also pointing to areas that may warrant further reflection or study.

Following five years of research and consultations, the ICRC published a new, updated Commentary on the Fourth Geneva Convention (GC IV) of 1949 in October 2025. GC IV is the cornerstone of protection for civilians in international armed conflict and occupation – protections that remain urgently relevant amid patterns of urban warfare, strikes on essential services, and persistent harm to people who are not, or are no longer, taking part in hostilities. The 2025 Commentary, following the interpretive methodology outlined in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, consolidates seven decades of practice, jurisprudence, and operational experience into a practical guide to applying GC IV’s safeguards effectively today.

Over the coming weeks, we are delighted to co-host a joint symposium with the editors of Just Security and EJIL:Talk!, sharing expert contributions on selected topics addressed in the updated ICRC Commentary on the Fourth Geneva Convention. We hope this analysis will help shed light on important aspects of the Fourth Convention that are explored in depth in the updated Commentary, outline developments in law, technology and language since 1949, and give readers an idea of what has changed since the initial ICRC Commentary on this Convention was published in 1958.

As Jean-Marie Henckaerts highlights below, a good faith interpretation and application of the Fourth Convention is indispensable: “it keeps interpretation anchored in the Conventions’ object and purpose, ensuring that their protective spirit prevails over technical evasions.” His following post, initially published on 21 October 2025, serves as an introduction both to the updated Commentary and to this symposium.

Naval warfare has undergone dramatic transformation, expanding across multiple domains and exposing civilian seafarers, infrastructure, and global supply chains to new and evolving risks. As modern maritime operations become faster, more complex, and more interconnected, long-standing legal frameworks face growing pressure to keep pace.

In this post, ICRC Legal Adviser Abby Zeith examines the changing character of naval warfare and questions whether the maritime domain should still be treated as exceptional. She explores how technological, operational, and geopolitical shifts intersect with existing international humanitarian law (IHL), and why renewed clarity from states is essential to protect civilian shipping, seafarers, and populations ashore.

Militaries are gearing up for confrontation on a new battlefield: the human brain.

While psychological operations aimed at deceiving enemies or manipulating soldiers and civilian populations have long been part of the military playbook, “cognitive warfare” marks a conceptual shift in which human cognition is framed as a “sixth domain” of military competition, alongside land, sea, air, cyber, and space.

In this post, ICRC Policy Adviser Pierrick Devidal offers an overview of the concept of “cognitive warfare” and examines the humanitarian concerns it raises. He argues that if our brains are to be treated as future battlefields, now is the time to consider how the risks can be prevented and mitigated.

The International Criminal Court recently issued its first conviction for gender persecution as a crime against humanity, alongside related convictions for rape as a war crime under international humanitarian law (IHL). These convictions signal expanding efforts to hold perpetrators accountable for violations committed during conflict, including against women and girls as well as on the basis of gender. This recognition aligns with the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda created by UN Security Resolution 1325. Yet, despite the clear intersection of IHL and WPS, these two frameworks have been largely siloed from one another. With the WPS agenda celebrating its twenty-fifth anniversary against a backdrop of global anti-rights and anti-gender backlash, it's more urgent than ever these frameworks are brought together.

In this post, Jessica Anania, a Conflict & Security Fellow at the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, outlines the strategic advantages of closer coordination between IHL and WPS when it comes to strengthening protection and accountability for women and girls. Key benefits of bridging IHL and WPS include filling in gaps within IHL’s existing protections to better reflect the realities of women and girls before, during and after conflict; expanding IHL’s impact through stronger recognition of gender crimes; countering non-compliance; and strengthening awareness of women and girls’ needs by addressing gender stereotypes inherent to IHL.

Many women and children are exposed to violence, exploitation and other risks, including death and family separation, during their migration journeys. Despite the recognition that gender and age shape migration experiences, there is limited data and analysis that systematically and directly addresses how and why migrant women and children go missing or become separated. To reduce this knowledge gap and identify steps to mitigate risks for women and children, the ICRC’s Central Tracing Agency and the Red Cross Red Crescent Global Migration Lab undertook research across the Americas, Africa, and Europe.[1]

In collaboration with 17 National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies,[2] we spoke to over 800 migrant women and children, families of missing migrants, and key informants to hear their stories, concerns, and proposed solutions. In this post, we present key insights from the recently published research reports that draw on migrants’ lived experience to identify drivers of deaths and separations, obstacles to maintaining contact and searching for their missing loved ones, and strategies to ensure the safety, dignity, and well-being of migrant women and children.

As cyber operations are increasingly taking place during armed conflicts, and this trend is likely to continue, certain specific protections afforded under IHL and identified in the physical world by the distinctive emblems of the Red Cross, Red Crescent, and Red Crystal must also be visible in an environment the drafters of the very first Geneva Convention in 1864 could never have imagined.

In this post, Samit D’Cunha, Legal Adviser at the ICRC, and Mauro Vignati, Technical Adviser at the ICRC, examine the rationale behind the Digital Emblem Project and the significant progress made in recent months. Drawing on ongoing standardization efforts and a growing list of supporters of the project, this post explores how a simple, globally recognizable marker is being developed to help distinguish specifically protected medical and humanitarian assets online.

The ICRC’s 2005 study on customary international humanitarian law – along with the free, public database launched five years later – arrived at a moment when the legal landscape of armed conflict was rapidly shifting. Mandated by the 26th International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, the study set out to map the customary rules governing contemporary warfare by systematically analyzing global state practice and opinio juris. Twenty years on, with more than 130 armed conflicts active worldwide, reassessing the study’s methodological contributions, its evidence base, and its impact on the regulation of both international and non-international armed conflicts offers a timely lens on how customary IHL continues to underpin protections for people affected by war.

In this post, ICRC Legal Adviser Claudia Maritano and members of the British Red Cross-ICRC customary IHL research team reflect on how the study’s rigorous methodology, global scope, and identification of 161 customary rules helped clarify gaps left by treaties, especially in non-international armed conflicts, and strengthen the practical application of IHL.

Large-scale armed conflicts consistently sever the systems that sustain civilian life, leaving populations without essential services or access to basic goods. International humanitarian law (IHL) sets out clear obligations for states to anticipate these foreseeable humanitarian needs and to ensure that impartial relief can reach affected communities swiftly and safely. Yet from customs hurdles to restrictive regulatory frameworks, many of the barriers to life-saving assistance are rooted not in conflict itself, but in peacetime choices.

In this post, ICRC Legal Adviser Ellen Policinski examines how states can proactively shape legal, administrative, and logistical systems that enable, rather than obstruct, humanitarian relief in moments of crisis. She underscores that meeting IHL obligations requires advance preparation – from easing import restrictions to ensuring postal and customs exemptions – so that when conflict erupts, assistance can move without avoidable delay.

The environmental toll of armed conflict is neither insignificant nor fleeting: it contaminates water, soil, and air, erodes ecosystems, undermines livelihoods, and burdens public health long after the fighting stops. The damage both mirrors and magnifies humanitarian crises, from Gaza’s mountains of debris to Ukraine’s flood-borne pollutants, to Sudan’s industrial contamination. Compounded by the impacts of the climate crisis, these environmental challenges only deepen the vulnerabilities of those affected by conflict. Understanding and addressing the interwoven impacts of conflict and the environment is essential for global climate, nature, pollution and sustainable development efforts, and to ensure that people can live and thrive in a healthy, secure and resilient environment.

In this post, part of the War, Law and the Environment series, the UNEP Disasters and Conflicts Branch reflects on its decades of work helping countries address these challenges, charting a path from emergency response to long-term recovery. Through science-based assessments, practical guidance, and strategic partnerships, UNEP is equipping states to address the toxic legacies of war, restore ecosystems, and build resilience into the reconstruction process. Recent UN resolutions, including UNEA’s 2024 consensus decision, underscore growing political recognition that protecting the environment in armed conflict is integral to peace and recovery. What emerges is a vision of environmental response not as an afterthought to war, but as a cornerstone of recovery, and an entry point to build back greener, fairer, and stronger in the shadow of destruction.

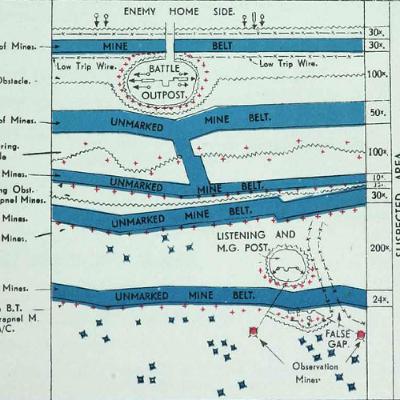

Five States Parties to the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention have recently submitted instruments of withdrawal, citing national security and military necessity, while at least one other has taken steps to “suspend” the Convention. These developments raise important questions about whether anti-personnel mines retain any meaningful military utility in contemporary conflict.

In this post, Erik Tollefsen, Head of the ICRC Weapon Contamination Unit and Pete Evans, Head of the ICRC Unit for Arms Carriers and Prevention examine this question from an operational perspective. They argue that advances in technology and the realities of modern warfare have significantly reduced the military relevance of anti-personnel mines, while their humanitarian consequences remain severe. They outline why some of the most frequently cited justifications – border security, the supposed benefits of “smart” mines, or perceived low cost – no longer withstand scrutiny, and why renewed interest in these weapons risks reversing decades of progress. The authors call on states to base decisions on rigorous, transparent assessments of current military relevance weighed against humanitarian and legal obligations. In a security environment defined by rapid innovation, they conclude that, now as at the Convention’s adoption 30 years ago, anti-personnel mines have no place on the modern battlefield – and that reaffirming the norm against their use is more urgent than ever.

More than 200 million people live today in contested territories – places where the authority of the state is challenged outright and armed groups exercise full or fluid control. This number has risen by 30 million since 2021. These are not distant statistics; each figure represents a person living in the shadow of competing powers, making difficult choices in an almost impossible environment.

How do people navigate the presence of multiple, often competing, armed actors? Is dignity found in defiance, or safety in uneasy compliance? How do families secure food, water or medical care when neither the state nor armed groups are able or willing to provide basic services? And, crucially, what can humanitarian actors do to better protect and assist those caught in these fractured landscapes?

In this post, and drawing on recently published research in Cameroon, Iraq and the Philippines, Arjun Claire, Senior Policy Adviser at the ICRC, and Matthew Bamber-Zryd, the ICRC’s Adviser on Armed Groups, offer five insights to help strengthen humanitarian responses in contested territories – insights rooted in the lived realities of the people who navigate them every day.

Restrictions on movement and access to medical supplies have become an often-unseen threat to health care in today’s armed conflicts. Even where hospitals are not attacked, the quiet tightening of supply routes can deprive them of the medicines, equipment, and basic services they need to function.

In this post, ICRC Legal Advisers Supriya Rao and Alexander Breitegger outline what the obligation to protect medical facilities means in practice, from allowing the passage of medical consignments to enabling essential services like power and water. They also describe how concerns about dual-use risks must be balanced against humanitarian needs, and highlight ongoing work under the Global IHL Initiative to identify good practices that help keep hospitals operating even in the most difficult conditions.

As artificial intelligence (AI) begins to shape decisions about who is detained in armed conflict and how detention facilities are managed, questions once reserved for science fiction are now urgent matters of law and ethics. The drive to harness data and optimize efficiency risks displacing human judgment from one of the most sensitive areas of warfare: deprivation of liberty. In doing so, AI could strip detainees of what remains of their humanity, reducing them to data points and undermining the core humanitarian guarantees that the Geneva Conventions were designed to protect.

In this post, Terry Hackett, ICRC’s Head of the Persons Deprived of Liberty Unit, and Alexis Comninos, ICRC’s Thematic Legal Adviser, explore how the use of AI in detention operations intersects with international humanitarian law (IHL), and why humane treatment must remain a human-centered endeavor. Drawing on the ICRC’s recent recommendations to the UN Secretary-General, they argue that while IHL does not oppose innovation, it sets the moral and legal boundaries that ensure technological progress does not come at the cost of human dignity.

When people go missing in war, their absence lingers far beyond the battlefield – splintering families, deepening social divides, and haunting political transitions. Yet amid this grief, the families of the missing often become unlikely peacebuilders: their search for truth draws them across old front lines, transforming pain into connection and personal loss into a collective force for reconciliation.

In this post, Jill Stockwell, Simon Robins, and Martina Zaccaro explore how families of the missing – through shared advocacy and dialogue – can reshape divided societies. Drawing on ICRC research from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cyprus, and Nepal, they show how families who once faced each other as enemies now work side by side, using their moral authority and lived experience to foster empathy, resist manipulation, and model the very reconciliation peace processes often fail to achieve.

When wars end, peace rarely begins overnight. It’s built, slowly and painstakingly, through acts that restore a sense of humanity where it was once suspended. Among these, how a society treats people it detains may seem peripheral, yet it can determine whether trust survives long enough for peace to take root. Humane detention, often overshadowed by more visible aspects of conflict recovery, is in fact one of the earliest and most concrete tests of readiness for peace. Each act of respect for law and dignity – registering a detainee, allowing a family visit, providing medical care, or releasing a prisoner when the reason for detention has ceased – helps reduce the harm that fuels revenge and instead preserves the fragile threads of trust that can bind divided societies.

In this post, Terry Hackett, ICRC’s Head of the Persons Deprived of Liberty Unit, and Audrey Purcell-O’Dwyer, ICRC’s Legal Adviser with the Global Initiative on IHL, show how compliance with international humanitarian law (IHL) in detention – while not a direct path to peace – can serve as a legal and moral bridge towards it, one rooted in dignity, accountability, and the quiet rebuilding of trust. By limiting suffering and safeguarding dignity, it helps prevent conflicts from eroding the institutions and confidence that societies need to recover.

Picture a potential future armed conflict: missiles and drones crowding the skies, uncrewed vehicles rolling across borders, and governments scrambling to coordinate their defences. Their conclusion: Every citizen is needed. Some collect and relay information about the approaching enemy into an artificial intelligence (AI) platform that supports military decision-making. Reservists join the ranks of the armed forces. Computer experts choose to contribute by conducting cyber operations aimed at disrupting military operations, sowing chaos among the civilian population, and harming the enemy’s economy. As the militaries on both sides rely heavily on digital communication, connectivity, and AI, the armed forces call on tech companies to provide cybersecurity services, computing power and digital communication networks.

In this post, Tilman Rodenhäuser, Samit D’Cunha, and Laurent Gisel from the ICRC, Anna Rosalie Greipl from the Academy, and Professor Marco Roscini from the University of Westminster (and former Swiss IHL Chair at the Geneva Academy) present five key risks for civilians, along with the obligations of both civilians and states, related to the involvement of civilians in information and communication technology (ICT) activities in armed conflict.

In line with its mandate, the ICRC engages with all parties to an armed conflict, including non-state armed groups. The ICRC has a long history of confidential humanitarian engagement with armed groups to alleviate and prevent the suffering of persons living in areas controlled by these groups. However, this engagement has become increasingly complex. Accordingly, the ICRC undertakes an annual internal exercise to evaluate the status of its relationships with armed groups and to identify developments to strengthen its future engagement worldwide.

In this post, ICRC Adviser Matthew Bamber-Zryd discusses key findings from the 2025 exercise. The ICRC estimates that 204 million people live in areas controlled or contested by armed groups. In 2025, there were more than 380 armed groups of humanitarian concern. A key development in 2025 is the ICRC's deepened engagement with non-state armed groups that are parties to armed conflict and bound by international humanitarian law (IHL), achieving significantly higher contact rates with these groups than with other armed actors. Yet engagement remains constrained by three major obstacles: deteriorating security conditions, operational constraints including limited resources and competing priorities, and state-imposed barriers, notably counter-terrorism legislation.