Discover Wavell Room Audio Reads

Wavell Room Audio Reads

101 Episodes

Reverse

Today, the British Army trains against a potential Russian enemy. Throughout the Cold War it trained against a possible confrontation with the Soviet Army and Warsaw Pact. In this respect nothing has changed. What has changed – self-evidently – is the Russian Army after three-and-a-half years of war in Ukraine. This article is about how the Russian Army fights in the war in Ukraine. It is not possible to say how it may fight in ten or twenty years. That caveat stated, insights can still be offered from what we observe today.

No tactical radio network

A first and fundamental point to understand about the Russian Army is that it lacks a functioning tactical radio network. Pre-war, the procurement of a modern, digital radio network was one of the biggest corruption scandals in the Russian MOD. Following the invasion, commentators quickly noticed the ubiquity of (insecure) walkie-talkies, as well as the general chaos of the invasion force. The reality is that just over 100 battalion tactical groups were sent over the border fielding three generations of radio systems connected in disparate, ad hoc nets (a British equivalent would be a force fielding Larkspur, Clansman and Bowman radios; most readers will not remember the first two). The loss of the entire pre-war vehicle fleets has exacerbated the problem; with the vehicles went the radios. Russian defence electronics industry does not have the capacity to replace this disastrous loss. It seems not to have tried.

So how does the Russian Army communicate? At tactical level it communicates with walkie-talkies (Kirisun, TYT, AnyTone, and others) and smartphones (on the civilian Telegram channel, although the MOD is about to roll out a new messenger system termed 'Max'). Starlink is widely used. As expected, Ukrainian EW daily harvests intercepts. Away from the mostly static frontlines, line, fibre-optic cable and HF radios are used.

The ability to communicate across voice and data nets, securely, is fundamental to an army. It is the lack of a functioning tactical radio network that has driven the Russian Army's tactics – you can only do what your communication system allows you to do.

No combined arms capability

The principal consequence of a lack of a functioning tactical radio network is that the Russian Army is incapable of combined arms warfare. The only observed cooperation between different arms is the now rare assaults involving perhaps one 'turtle tank' (essentially a tank resembling a Leonardo da Vinci drawing, covered in layers of steel plates and logs), and two or three similarly festooned vintage BMPs). They don't survive although one 'turtle tank' recently required over 60 FPV drone hits before it was definitively destroyed (the crew long abandoned their dangerous box and fled).

Following on, the Russian Army is incapable of coordinating an action above company level. The last period when true battalion-level operations were attempted was in Avdiivka in the winter of 2023-2024. However, these involved vehicles simply lining up in single file on a track and playing 'follow the leader'. Similar tactics were seen in the re-taking of the Kurshchyna salient in Kursk this spring, which was also the last period that witnessed sustained attempts at mounting company-level armoured attacks (there was an odd exception to this rule at the end of July on the Siversk front; all the vehicles were destroyed).

The level of operations of the Russian Army is company and below.

No joint capability

From the start of the invasion it was evident the Russian Air Force was incapable of co-ordinating a dynamic air campaign, air-versus-air, or in support of ground forces. By the autumn of 2022 Russian strike aircraft stopped crossing the international border altogether due to losses. The first glide bombs were recorded in the spring of 2023 (these are launched from Russian air space). Today, a daily average of 80 strike sorties and 130 glide bombs are recorded. These mainly target frontline pos...

Introduction

The Red Sea crisis has settled into an uncomfortable new normal. While the initial shock caused by the use of anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBM) has faded, the strategic implications of the Houthi campaign remain dangerously under-analysed in the context of future British Naval Doctrine. For the Royal Navy, the conflict would appear to cast a shadow over amphibious operations in littoral waters, where both the Carrier Strike Group (CSG) and the Littoral Response Groups (LRGs) are expected to conduct their operations. The Houthi campaign has inadvertently provided an example of a scalable, repeatable model of sea denial that fundamentally challenges the operating and financial rationale of Western naval power projection.

The Houthi Model involves the integration of sensors and shooters at the state level with the expendability and mass of non-state actor operations. This model poses a significant challenge for the Royal Navy, which relies on low-density, high-value assets.

The Tyranny of the Cost-Exchange Ratio

The frightening mathematics of modern air defence are grounded in the lessons learned from the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. In the first few months of the Red Sea conflict, British destroyers, notably HMS Diamond, excelled at shooting down wave after wave of hostile tracks. However, there was an unsustainable price to pay.

The Houthis' Shahed-136 derivative costs approximately $20,000. The missile required to intercept it, an Aster-15 or Sea Viper, costs at least £1 million. While individual engagements can be justified by the value of a destroyed merchant vessel or a destroyer providing escort, the economics of sustained engagement are financially disastrous.

This creates a magazine depth problem that the CSG must confront. A Type 45 Destroyer has 48 vertical launch (VL) silos. In a saturation attack scenario, precisely the type the Houthi Model promotes, a destroyer may expend its entire primary magazine in minutes, shooting down targets costing its adversary less than a basic rigid-hulled inflatable boat (RHIB). It should be noted that at present, the Royal Navy can not replenish a surface vessel's VL silos whilst at sea.

Should the UK CSG deploy to the Indo-Pacific, it would face the People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). However, the Houthi Model demonstrates that the PLAN need not risk its own high-value hulls to mission-kill a Queen Elizabeth-class carrier. It only needs to provide a proxy or 'maritime militia' swarm with sufficient cheap, attritable effectors to force the CSG to exhaust its magazines. Once the escorts are out of ammunition, the carrier becomes operationally irrelevant, forced to withdraw without a single capital ship being sunk.

The Littoral Response Group in Crisis: The Decommissioning Dilemma

The consequences for the Littoral Response Group could be the most profound. The current construct envisions the use of Bay-class and Albion-class vessels in the littoral zone to conduct 'raids' and achieve 'strategic effects' via the force insertion of Commandos. However, the basis for such an operational construct has now fundamentally changed.

In March 2025, the Ministry of Defence undertook the decommissioning of HMS Albion and Bulwark, the Royal Navy's two Albion-class landing platform docks. This was an exercise in cost-cutting that has resulted in a major capability gap. This capability gap now exists at a time when there is a considerable change in the doctrine surrounding amphibious operations. Albion-class vessels were designed to deliver amphibious landing forces at the brigade level. Their absence means that the Royal Navy has to rely on three Bay-class Landing Ship Docks, vessels that are already under considerable pressure due to crewing deficits within the Royal Fleet Auxiliary.

The capability gap is significant, as there are now no Bay-class vessels available to conduct sustained operations. With the Albion-class now retired, the capability deficit is pronounced. The lightweight, a...

The Houthis

Necessity is a dark cloud that often gives birth to innovation in the turbulent arenas of contemporary conflicts. That 'dark cloud' – the existential threat – can act as a powerful catalyst for ingenuity, particularly in 21st-century conflicts. A very low-profile, yet dramatic form of this change is underway as terrorist and insurgent groups use commercial unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) – not just to conduct occasional attacks, but to provide a system of permanent, industrial-level resupply operations. This development makes fortified borders and patrolled roadways even more obsolete across the Sahel, to Yemen, and in South Asia.

This is not a tactical gimmick. It is a strategic development. What started as experimental applications of shelf-storey drones has evolved into a stable aerial logistics chain that can transport 300-800 kilograms of explosives, electronic parts, munitions and vital materiel each week over hundreds of kilometres of enemy-controlled land.

Terrorist groups establish their continuous logistical 'airborne' pipelines using fixed-wing UAVs, each carrying payloads of 5-20kg over distances of 100-400km per flight. These drones are now built using parts that cost less than 2500 US dollars each, with jam-resistant navigation, including SpaceX Starlink ROAM terminals, that can provide satellite-based freedom even in electronically hostile environments. These operations create long-range air bridges that evade ground interdiction and exploit vast uncontrolled airspace, unlike headline-grabbing isolated attacks.

The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara

For instance, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) has wreaked havoc across the Mali-Niger-Burkina Faso tri-border region in the Sahel. ISGS uses nocturnal relay chains of short-hop drone hops to ferry ammunition and IED precursors through deserts, where the use of ground troops becomes risky due to the ambushes of French-supported forces or local militias. A 2025 report by the Institute of Security Studies states that Sahelian terrorist cells, armed with Chinese-sourced commercial quadcopters as well as fixed-wing drones, acquired via Algeria and Libya, have adapted drones with longer battery life and thermal imaging. This has maintained offensive operations in remote outposts, regardless of Wagner Group patrols. This phenomenon has contributed to the UN estimate that terrorism based in Sahel contributed to more than 40 per cent of global terrorism fatalities in the first half of 2025.

The Houthis in Yemen

The Houthis have also developed the infrastructure of drone logistics, turning it into a geopolitical asset in Yemen. They launch payloads more than 300 km from mountain strongholds to reach the adjacent territory, bypassing both heavily monitored land and sea borders. In October 2025, the Pentagon evaluations and U.S. naval intercepts in the Red Sea verified the shipments of dismantled drone engines and guidance kits that were delivered in parts by UAVs. Every sortie is less than a thousand dollars, and interceptor assets are over a hundred thousand dollars, continuing the Houthi campaign against Bab-el-Mandeb shipping and disabling multibillion-dollar border walls.

Tehrik-i-Taliban in South Asia

This trend extends to South Asia, where Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) confronts Islamabad on the Durand line. Although Pakistan has maintained fencing and towers since 2017, TTP forces in Afghanistan's Kunar and Nangarhar provinces carry out nocturnal sustainment flights of small arms, batteries and IED components directly into Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province. A recent analysis by the Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies recorded a 30% surge in TTP attacks this year. This escalation has forced the military to divert resources to counter-drone efforts, exposing the futility of physical border barriers against overhead supply.

Why conventional methods do not work

These instances demonstrate that the traditional method of counter-ter...

'Power, violence and legitimacy are fragmenting, and modern conflict is starting to behave accordingly'1

Introduction

It's hard to shake the feeling that conflict no longer behaves the way we expect it to. Wars don't end cleanly, responsibility is always blurred, and decisions with real consequences seem to be made everywhere and nowhere at once. We sense that something has changed, but rarely have the space to stop and ask why. This isn't an attempt to predict the next war or sound the alarm. It's an effort to make sense of why power, violence and accountability no longer behave the way we assume they do, and what that could mean for states and societies that still expect to manage them.

Modern conflict is no longer defined by the Western conception of war as a discrete event led by states, fought by armies, and concluded by treaties. It has become a fluid spectrum shaped by states, private actors, technologies, algorithms, and societies that no longer share a common centre of gravity. The result is a geopolitical environment where the means of violence are distributed, authority is conditional, and conflict increasingly persists rather than resolves. That shift is hard to miss for anyone paying even casual attention to current events.

Conflict Without Resolution

In Ukraine, the fallout from Andriy Yermak's resignation in November 2025 was not just another political headline. It exposed a quieter competition over who shapes the end of the war, who decides the terms of security, and which interests gain access and influence when the war eventually winds down. It is a reminder that power has never been centralised in one place, and that competing interests are now shaping outcomes more openly than before. States still matter, but they no longer control the direction of conflict or the timing of peace alone. It shows how even in a major interstate war, control over outcomes is dispersed across political factions, private funders, foreign backers and societal forces.

Power Beyond the State

In Venezuela, tensions following the American strike has little to do with drugs, rhetoric or posturing alone. Politics matters, but so do the stakes beneath it: the largest proven oil reserves on earth, critical minerals and control of commercial advantage in a region where global competitors are increasingly active. This is the type of dispute where state power, private interests and informal networks blend into one another, and where none of these actors operate in isolation or according to national logic. It is a textbook case of a conflict shaped more by markets, resources and informal networks than by state intention.

In the Middle East, Israel's simultaneous operations across Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and the West Bank show how modern warfare behaves when too many actors hold the capacity to escalate. Fronts no longer open and close; they bleed into one another, influenced not only by governments but by proxies, foreign backers and interests that do not wear national uniforms. The result is not confusion, it is complexity. Together, these overlapping fronts reinforce a world in which the power to escalate is no longer held by states alone.

The Fracturing of Monopoly, Not the State

These conflicts should not be lumped together, but they reveal a structural reality that they now share: the state is still powerful, but it is no longer the only force that matters. Too many actors now possess the means to shape violence, stall peace or influence outcomes from outside the traditional architecture of a government. The modern battlefield has matured into something closer to a marketplace of capabilities, incentives and interests than a domain controlled solely by states.

Western strategic thinking has long struggled with this shift because its definitions of war remain narrow. Other traditions have always recognised a wider spectrum: the Russian military and strategic literature use the words borba ('struggle') to capture political, informational ...

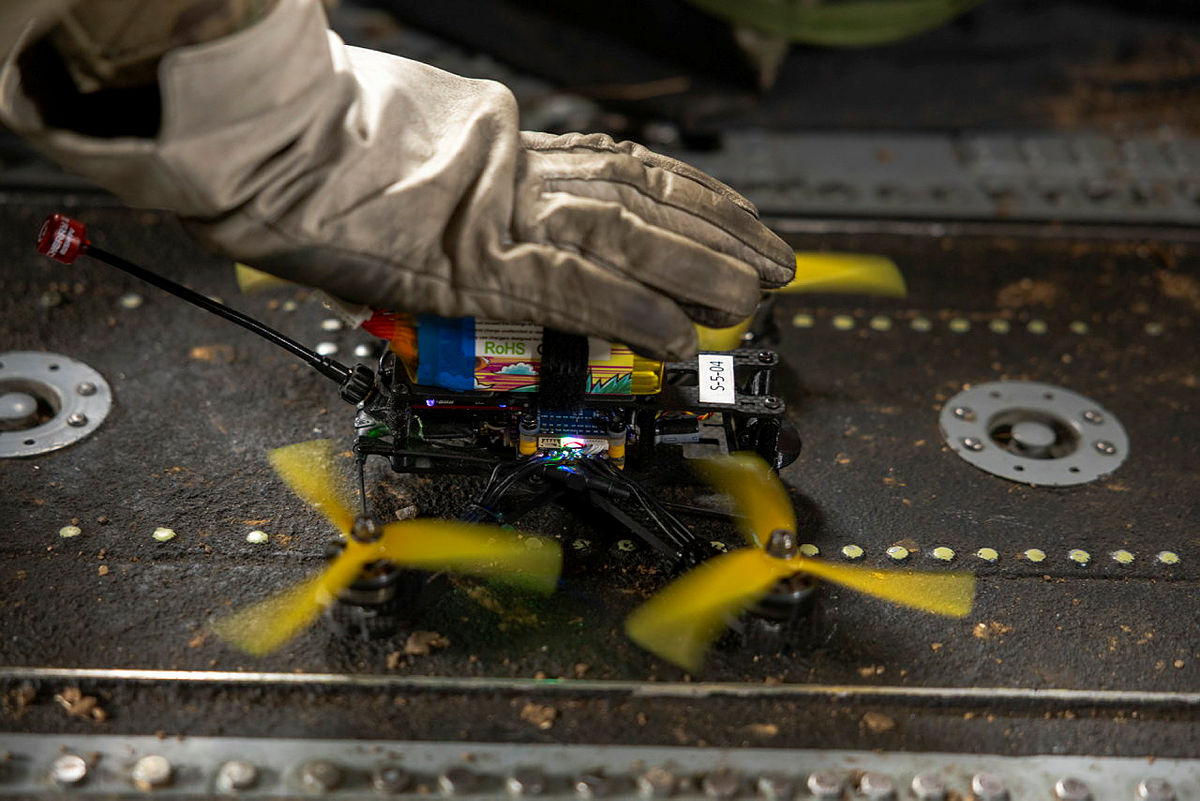

The Russo-Ukrainian War is a crucible of modern military innovation and has seen adaptation at

every echelon, which the British Army is seeking to learn lessons from. In particular, the

emergence of brigade-level commercial contracting within the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) has

captured the imagination of its commanders. However, such an approach has inherent

opportunities, risks and consequences. Ultimately, a Ukrainian brigade is not analogous to a British

one and the Army has higher echelons of capable Division and Corps headquarters. Through a

blended approach, these can serve to manage a system of 'decentralised' commerical contracting

whilst mitigating the risks of tactical and institutional fragmentation. The British Army has to be

discerning in which lessons it chooses to learn and adapt from.

Over the course of Russo-Ukrainian War, beginning with the seizure of Crimea in 2014 and

through the full-scale invasion in 2022, the AFU has "radically pivoted its approach to military

innovation" and evolved a dual-track scheme to develop and procure military technologies. On the

one hand, it operates a 'centralised' system orchestrated by the Ukrainian government and AFU

command headquarters. This principally coordinates the flow of western-supplied equipment and

seeks to manage sovereign industrial output. On the other, a 'decentralised' system has evolved

with individual AFU brigades working directly with the commercial sector. By this latter approach,

technology and equipment moves from factory to frontline at ever increasing speeds but this

comes at the detriment of force standardisation and integration.

This decentralised model of brigade-level procurement is attractive for those seeking to address

criticisms of the MOD's "sluggish procurement processes". But the question is not whether to

replicate the entire approach, which emerged from existential necessity to meet specific

operational conditions, but rather to discern which elements might be adopted. The goal being to

enhance MOD procurement without undermining the coherence that British industry and military

requires. To do so it must understand the genesis of the AFU's brigade-level procurement model,

consider the relative weight of opportunities vs risks and adapt them to Britain's own unique

context.

Origin Story

The Ukrainian state in 2014 lacked sufficient funds to address its force's equipment deficits and

regenerate units, which saw private citizens from across civil society fill the gap. This social

phenomenon accelerated in February 2022 as numbers joining the AFU increased, with many of

the new soldiers bringing significant personal wealth and business resource with them into service.

Commerical enterprise and industrial companies became intertwined at the lowest tactical levels

with frontline units. These in turn – which until recently were the largest AFU tactical formations –

developed an entrepreneurial attitude to procurement.

Thus emerged the 'decentralised' approach evident today. It grew organically to bypass traditional

bureaucratic channels to enable speed of delivery and embed battlefield feedback into industrial

procurement cycles. Critically, it also emerged in the absence of functional headquarters (for

example Division and Corps) between the brigades and the AFU central command. The system

was neither designed nor deliberate and as a result capacity varies across brigades. This is

because of three fundamental tensions: tactical agility vs force standardisation; operational

responsiveness vs industrial sustainability; and strategic mobilisation vs coherent force design.

Tactical Agility vs Force Standardisation

Brigade contracting has delivered a procurement cycle measured in days rather than months and

years. Ukrainian forces can get drones, communications equipment and logistics enablement with

unprecedented speed, allowing them to respond to Russian Forces in near-real time. CEPA noted

the AFU's "response to the logistical challenges o...

Incremental adaptation in modern warfare has astonished military observers globally. Ukraine's meticulously planned Operation Spider Web stands as a stark reminder of how bottom-up innovation combined with hi-tech solutions can prove their mettle on the battlefield. It has also exposed the recurring flaw in the strategic mindsets of the great powers: undermining small powers, their propensity for defence, and their will to resist. Having large-scale conventional militaries and legacy battle systems, great powers are generally guided by a hubris of technological preeminence and expectations of fighting large-scale industrial wars. In contrast, small powers don't fight in the same paradigm; they innovate from the bottom up, leveraging terrain advantage by repurposing dual-use tech, turning the asymmetries to their favour.

History offers notable instances of great power failures in asymmetric conflicts. From the French Peninsular War to the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, these conflicts demonstrate the great powers' failure to adapt to the opponent's asymmetric strategies. This is partly due to their infatuation with the homogeneity of military thought, overwhelming firepower and opponents' strategic circumspection to avoid symmetric confrontation with the great powers.

On the contrary, small powers possess limited means and objectives when confronting a great power. They simply avoid fighting in the opponent's favoured paradigm. Instead, they employ an indirect strategy of attrition, foster bottom-up high-tech innovation and leverage terrain knowledge to increase attritional cost and exhaust opponents' political will to fight. Similarly, small powers are often more resilient, which is manifested by their higher threshold of pain to incur losses, an aspect notably absent in great powers' war calculus.

Operation Spider Web

In the Operation Spider Web, Ukraine employed a fusion of drone technology with human intelligence (HUMINT) to attack Russia's strategic aviation mainstays. Eighteen months before the attack, Ukraine's Security Services (SBU) covertly smuggled small drones and modular launch systems compartmentalised inside cargo trucks. These drones were later transported close to Russian airbases. Utilising an open-source software called ArduPilot, these drones struck a handful of Russia's rear defences, including Olenya, Ivanovo, Dyagilevo and Belaya airbases. Among these bases, Olenya is home to the 40th Composite Aviation Regiment-a guardian of Russia's strategic bomber fleet capable of conducting long-range strikes.

The operation not only damaged Russia's second-strike capability but also caught the Russian military off guard in anticipating such a coordinated strike in its strategic depth. Russia's rugged terrain, vast geography and harsh climate realities shielded its rear defences from foreign incursions. Nonetheless, Ukraine's bottom-up innovation in hi-tech solutions, coupled with a robust HUMINT network, enabled it to hit the strategic nerve centres, which remained geographically insulated for centuries.

Since the offset of hostilities, Ukraine has adopted a whole-of-society approach to enhance its defence and technological ecosystem. By leveraging creativity, Ukraine meticulously developed, tested and repurposed the dual-use technologies to maximise its warfighting potential. From sinking Russia's flagship Moskva to hitting its aviation backbones, Ukraine abridged the loop between prototyping, testing, and fielding drones in its force structures.

Underrated aspects?

Another underrated aspect of Ukraine's success is the innovate or perish mindset. Russia's preponderant technology and overwhelming firepower prompted Ukrainians to find a rapid solution to defence production. Most of Ukraine's defence industrial base is located in Eastern Ukraine, which sustained millions of dollars' worth of damage from Russia's relentless assaults. Therefore, the Ukrainian government made incremental changes in Military Equipment ...

As Russia launches the next phase of its Campaign, Great Powers are Competing.

So why is the UK on the Bench?

With overt and covert probing across Europe, a newly undeterred Russia has entered the next phase in its War with the fracturing West. Rapidly developed on Ukraine's battlefields, Russia is deploying its newfound technological advantage over the West to penetrate the breadth and depth of our continent.

The UK needs to make a huge strategic choice today – do we want to put our Great Power pants on, match our ambitious words with the necessary resource, and compete – or do we let others write our destiny?

To be a great power is to choose.

Introduction

The liberal world order is gone; we are living in an era of great power competition. The rest of the world knows this, but despite our collective nuclear powers, huge GDP, world leading universities, manufacturing base and tech sectors, the UK and key European nations are sat on the bench. Our ambitious Ends in Ukraine unmatched by the necessary Ways and Means. As Russia probes beyond Ukraine, our words – unmatched by deeds – draw obvious parallels with 1914 where miscalculation, uncontrolled escalation and the absence of a mechanism to manage great powers resulted in world war.

Strategic Dissonance

Nowhere is this clearer than with the UK's recent alphabet soup of grand strategy documents. The SDR, the NSS, the NIS all explicitly accept the arrival of Great Power Competition, and all fail to connect the Ways and Means necessary to compete in it or propose a mechanism for managing it.

These national 'strategies' are risky. Firstly, they avoid the profound changes to our state machinery necessary for the management of Great Power Competition. Secondly, they allow political leaders to fudge, pretending they can both defend our nation and maintain unprecedented welfare spend. They can't. Thirdly, it is simultaneously bellicose whilst spiking our generals' guns. The limited increase in UK defence spend to ~3% arrives after the most likely window for great power conflict (2026-2029).

Great Powers must be both able and willing

To be a Great Power you must choose to be one. Russia, by force of will, is punching well above its weight, yet commentators overly focus on its relative GDP and Defence spend, somewhat missing the point. Russia is a Great Power precisely because it combines considerable mass and capability with the choice to deploy it – whether we like it or not. It has chosen to mobilise its populous and its industry, it has chosen to integrate rapid technological advances into its arsenal at the speed of relevance. The UK and other European nations manifestly have not.

We chose not to match our Means to our Ends. When Ukraine was invaded, Boris Johnson set the ambitious (and noble) End State: 'Russia must fail in Ukraine and be seen to fail'. However, our atrophied state machinery failed to allocate the commensurate Ways and Means to achieve this goal. Critically, the safety mechanism failed to highlight the mismatch and force our leaders to choose: Either upgrade our ways and means or downgrade our Ends. This dynamic was replicated across Western capitals, compounding this strategic failure. The US distancing itself and turning off critical capabilities at no notice saw the entire game change – ruining the West's strategic planning assumptions.

Consequently, Russia is attriting its way toward victory. With Western support fracturing and the frontline moving forward, Russia is winning, and Ukraine is losing. But this direction of travel affects far more than just Ukraine.

Whilst Russia has historically always held the advantage of mass against European armies. The grand strategy changing moment is seeing Russia develop Technological Advantage over the West in Ukraine. Simultaneously exposed daily to Western technology and trialling Chinese and Iranian prototypes on Ukraine's battlefields, Russia is learning fast and increasingly able to integrate emerging, decisive t...

"The nation that will insist on drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking by cowards."

~ Lt Gen Sir William F. Butler (1838-1910)

In the British Army we pride ourselves on our readiness. Prowess in physical fitness, tactical decision-making and speed of action lie at the forefront of our profession. But there's one form of readiness that's often overlooked. It doesn't come from kit, drills or doctrine - it comes from the mind.

Intellectual curiosity is the drive to ask questions. To explore ideas and seek deeper understanding that isn't just academic. It's a vital trait of the modern professional soldier and, if you're wearing the uniform, it belongs in your belt kit.

Whether commanding or following, whether in a platoon or a brigade HQ, curiosity sharpens your edge. It helps you adapt faster, lead better and think deeper. It's not about having all the answers - it's about having the habit of asking better questions.

Curiosity makes you Operationally Agile

Today we are constantly reminded that the modern battlefield is ever changing and unpredictable. Hybrid threats, cyber warfare, AI, drones and information operations demand more than muscle memory. They demand mental agility. Soldiers who read widely, study adversary doctrine and reflect on historical campaigns build the cognitive flexibility to pivot under pressure. You don't need a PhD to be curious and it isn't just an officer sport. All ranks need the discipline to keep learning, even when the tempo is high: the tactical battle moves faster than the operational one.

So what? Practical actions:

1. Read one article by Friday each week from a defence journal, historical case study or foreign doctrine summary. Start with RUSI, Wavell Room, CHACR or the British Army Review. Share an insight on Monday.

2. Join / start a Unit PME group - keep it informal, short, and relevant. One case, one question, 30 minutes, weekly or fortnightly, open discussion.

3. Find time in your schedule to scan open-source on military and defence topics. Ask: "What would I do if I were them?" The Institute for the Study of War is excellent for both the Russo-Ukrainian War and the Gaza conflict.

Curiosity isn't a distraction from the day job - it's preparation for operations. It's what lets you spot patterns others miss, challenge assumptions, and make decisions that stand up under scrutiny. In short, it's tactical advantage in mental form.

Curiosity strengthens Ethical Command

Contrary to popular belief (mostly how it's portrayed in films!), military leadership isn't simply about issuing orders. It's about making decisions that hold moral weight. Whether you're dealing with civilians in a conflict zone, navigating the grey areas of rules of engagement or fighting high intensity peer-on-peer war, ethical clarity matters. Soldiers who engage with philosophy, law and cultural studies are training their intellectual and moral reasoning like they train their marksmanship.

So what? Practical actions:

1. Investigate one case study per month from recent operations or historical dilemmas. Ask: "What would I do?" and consider the moral, ethical and tactical challenges.

2. Discuss moral challenges with your team - use real-world examples, not hypotheticals. Keep it grounded.

3. Explore cultural terrain before deployment - language basics, local customs, and historical context build empathy and reduce friction.

Curiosity helps you see the human terrain more clearly. It gives you the language to explain your decisions, the empathy to lead with integrity and the confidence to act when the right choice isn't the easy one. In a profession built on trust, that matters.

Curiosity builds a Better Army

The British Army isn't just a fighting force - it's a living and learning organisation. Doctrine evolves, technology changes and the enemy adapts. If we want to stay ahead we need soldiers who think critically, challeng...

Introduction: Defence as an engine for growth

The government's Defence Industrial Strategy 2025 (DIS25) is clear that "business as usual" in procurement is no longer an option. Defence has been placed at the heart of the UK's modern industrial strategy, identified as one of eight priority sectors to drive economic growth and resilience.

The strategy is frank in its diagnosis of the current system's weaknesses. Defence investment and economic strategy remain misaligned. Procurement processes have failed to adapt to an era where emerging technologies are reshaping warfare faster than at any point in living memory. Structural inefficiencies - from misaligned incentives to poor competition and weak exports - have left the UK industrial base struggling to deliver at the pace and scale required.

DIS25 calls for something different: procurement that reduces waste, accelerates innovation, empowers SMEs, and crowds in private capital. It seeks to create a vibrant defence technology ecosystem, one where delivery is faster, risk is shared more equitably, and capability can spiral forward through rapid increments. The ambition is to transform the relationship between government and industry, so that defence becomes not just a consumer of technology but a driver of economic productivity.

This context sets the stage for the idea of "mission partnership." The term is gaining currency across defence, but its meaning remains contested. At its best, it represents a practical shift in how programmes are delivered: a relationship structure where incentives, accountability and behaviours are aligned to outcomes. At its worst, it risks becoming a hollow buzzword, a softer synonym for "contractor" that re-badges old models without changing the fundamentals.

The question this paper explores is whether mission partnerships can provide the practical vehicle through which the ambitions of DIS25 are realised. It argues that they can, but only if approached seriously: as a means of reshaping delivery behaviours, not simply as a new label for old practices.

Why the system struggles today

The weaknesses identified in DIS25 are not new. They are the product of decades of choices and cultural habits that have left the system ill-suited to today's demands.

Policy pressure for pace, but institutional drag. Ministers have repeatedly signalled the need for faster delivery. The Integrated Procurement Model (IPM) commits Defence to deliver major equipment programmes within five years and digital programmes within three - targets that would have been unthinkable even a decade ago. Yet the approvals and governance cycles underpinning procurement remain rooted in Cold War-era timelines.

Churn widens the knowledge gap. High turnover across MOD, particularly in technical and engineering roles, erodes institutional memory. Programmes lose continuity, forcing new teams to relearn the same lessons and repeat the same mistakes. This constant rotation undermines trust between customer and supplier, creating a public-private knowledge gap that grows wider with every cycle.

Outsourcing legacies and switching costs. Two decades of outsourcing have left Defence dependent on a limited set of suppliers. Relationships have become brittle, with high switching costs that make even obvious changes operationally risky. Far from creating a competitive marketplace, outsourcing has often entrenched incumbents, leaving government hostage to long-term contract dependencies.

Blurry boundaries and accountability. Too many programmes begin with contract mechanics rather than mission outcomes. Assurance is treated as paperwork to be satisfied, not as a shared responsibility for safety and performance. The result is a culture where suppliers do what the contract says, not what the mission requires.

The combined effect is predictable: while policy demands agility and tempo, the system continues to generate delay.

A shifting moment in defence innovation

The environment, however, is shifting. T...

The Greco-Turkish War was one of the largest and most consequential conflicts of the interwar period, spanning the period between World War I and World War II. It was a significant factor in the overall trajectory of the modern Middle East. The Hellenic Kingdom looked to expand its territory to connect with the Greeks of Asia Minor.

In contrast, the nationalist forces under Mustafa Kemal looked to repel the Greek army and simultaneously expel foreign militaries to create a Turkish state. The war intertwined the Entente powers and revealed key lessons in logistics, the importance of a competent officer corps, and the use of key terrain to a defensive advantage, insights that can be studied for modern warfare today.

Beginnings of the Greco-Turkish

Against the backdrop of the capitulation of the Ottoman Empire, the remaining territories of the Middle East were placed under zones of influence (Sykes-Picot). In contrast, Asia Minor was put under full military occupation by several nations. The remnants of the Ottoman Empire were carved into a rump state by several nations.

Turkish nationalist forces would conduct an insurgency led by Mustafa Kemal, a skilled military commander who had defeated British forces at Gallipoli, thereby securing their own state without foreign occupation. The Entente was overstretched, and its citizens felt the economic brunt of WWI, which made it hard for countries such as the UK and France to allocate sufficient forces capable of defeating the factions of Turkish nationalists. Instead, the British would support a key ally in the Mediterranean to defeat the Turkish army - the Hellenic Kingdom of Greece.

During WWI, the Hellenic Kingdom, overseen by King Constantine I, initially decided to remain neutral despite having a pro-German government. This act caused anger among the Entente and pro-intervention Greek faction (the Venizelists), which resulted in Britain, France, and the latter exiling the then-monarch.

The new government, led by Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, adopted a core policy of irredentism regarding the historical Greek lands of Asia Minor, known as the Megali Idea. Furthermore, alongside Armenians, the remaining Greeks under the empire suffered from gruesome massacres amounting to genocide at the hands of the Ottomans in regions such as Eastern Thrace and Pontus, which also became another factor to initiate the war.

With the military backing of London and Paris, who sought to quell the Kemalist insurgency that posed a threat to their zones of influence in Asia Minor, Athens initiated the Greco-Turkish War on May 15, 1919, during the naval landing in Smyrna.

Early Hellenic Army Victories

The Hellenic expeditionary army quickly secured the Greek mandate of Smyrna, then secured the outlying cities of Aydin, Menemen, Bergama, Ayvalik, and Cesme. After consolidating tens of thousands of troops, the British and Hellenic army would move to secure cities near the Sea of Marmara during the 1920 summer offensive.

The Greek army captured the cities of Panormos, Izmit, Mudanya, Bursa, and Usak, securing much of Western Anatolia for both Athens and London. A Turkish counterattack at Gediz proved inconclusive before the winter set in.

In Greece, King Alexander died from a monkey infection, and citizens felt from WWI and now feeling exhausted from an inconclusive campaign at the time in Asia Minor. A pro-royalist faction would win the upcoming elections, which would oust Venizelos as PM, who was replaced by Dimitrios Gounaris. The November 1920 elections would play a consequential turning point in the war going forward in 1921 and 1922.

Athens Overstretched Its Logistics and Allied Support Wears Thin

Instead of continuing to secure the coastlines where the Hellenic and British navies could provide maritime and logistical support, the Greek army pushed into Central Anatolia to defeat the Turkish nationalist forces for good. Later in the war, several Turkish factions organized into a more cohesive...

Editor note: this article was first published on angrystaffofficer.com here.

Much has been written elsewhere regarding the unforgivable sin of failing to plan for known contingencies. Whatever one thinks of the current changes undergoing the United States Army, the least controversial thing to be said about them is that they certainly represent a change from what has come before. And regardless of what one thinks, or refuses to think, about their merit, one can say one other thing for certain: they will eventually yield. Sooner or later, the "idiosyncrasies" of the current administration will again be replaced by "regular order". They must, the only question is how long will that transformation take. As members of the profession of arms we must at least consider how we will collectively re-establish some of the fundamental characteristics and capabilities of our military in the period that follows.

This is essential, because any period of chaos or lack of resolve on our part has the potential to imperil national defense. Without a plan, what could be a very bumpy transition could give rise to an exploitable opportunity on the part of America's enemies to damage American interests, threaten America's overseas holdings, gain footholds in the "near-abroad", or threaten mainland America itself. The US Army's unshakable contract with the American people to fight and win the nation's wars by providing prompt, sustained land dominance across the full spectrum for conflict does not leave a lot of time for navel gazing during periods of uncertainty or of transition. In so far as that political uncertainty may unavoidably involve our Army, it is our responsibility to plan our way to the other side of it so that we may safeguard essential capabilities and be in a position to continue mission.

Retaking the moral high ground (rule of law)

The current administration's problematic relationship with the principles that inform the just use of force, such as the rule of law and the laws of land warfare, have been comprehensively documented elsewhere. Recent examples, in the form of exploding Venezuelan fishing boats accompanied by official pronouncements of indifference to the legal niceties of such action, make the direction we are moving in all too clear. What concerns us here is how best to put Humpty Dumpty back again after he has been comprehensively damaged.

Respect for the law that underpins the just use of force, and especially the various international regimes that support it, is difficult to build and easy to dismantle. This is especially the case where the offending party has heretofore held a pre-eminent role in maintaining the status quo. As America abandons her post as the guardian of international law and of the rules-based international order to seek a role as one among several regional hegemons this will, by design, create a destabilizing environment for smaller nations and could lead to the readjustment of borders through conflict.

Thinking through to a future where America may once again seek to champion a rules-based international order, how might we, as nation and as an Army, seek to incentivize participation by smaller nations who we may have earlier abandoned to their fate? I would suggest, ironically, that by maintaining our military strength and capabilities we may again be able to benignly bully the world in a multilateral rules-based order that transcends "the law of the jungle" as we did in the post WWII period. More than that, we would have to identify and maintain reservoirs of good practice and learning that survive the current period - such as the jurisprudence of the International Criminal Court, independent centers for the study of international law (in so far as our institutional ones do not avoid becoming fatally compromised), and independent expertise to whom we might have resort when we need them to rebuild our own institutional capacity.

Rebuilding academic infrastructure

Similarly, the loss of academic...

Britain's long awaited Defence Industrial Strategy 2025 (DIS 25) has been released. It commits the Government to the largest sustained uplift in defence spending since the Cold War and seeks to complement the ambition of Strategic Defence Review 2025 (SDR 25). It sets a short-term target of raising spending from 2% of GDP to 2.6% by 2027, declaring an "ambition" in the medium term for 3% by 2030 in the next Parliament. Longer term it outlines a "historic commitment" to reach a target of 5% alongside other NATO allies by 2035. The investment trajectory the strategy sets out seems intent not only to underwrite British national security but to position its defence industry as a key engine of sovereign economic growth, regional regeneration and technological capability development.

DIS 25 follows close on the heels of the recent announcement of a successful £10bn contract being signed for the UK to supply the Norwegian navy with Type 26 anti-submarine frigates. Its release also coincides with the Britain's flagship defence industry sector event Defence and Security Equipment International 2025 (DSEI 25) in London that serves as a physical totem of the Government's intention to encourage domestic and international commercial interest.

The 108-page strategy document contains suitably impressive numbers related to investment allocations. UK Defence Innovation has been tasked to "invest in [Britain's] most innovative defence companies" with a ring-fenced annual budget of £400 million, plus a mandate that 10% of its equipment procurement is spent on novel technologies. Likewise, £15 billion has been committed to the "sovereign warhead programme" and a further £6 billion to "strengthen our supply chains… in munitions this parliament". Efforts have also been made address procurement efficiency with the National Armaments Director being given authority of a "new segmented approach". Coupled with a commitment to a five-year, proactive forecasting process promises to reduce the need for emergency budget supplements and enhance market trust.

Reference is also made throughout to wider Government targets that promise to "reduce administrative costs of regulation to business… to create a regulatory environment fit for the current era of threat". Taken on face value, there is much to be optimistic about.

For the British Army there is much to be encouraged by. Faster contracting and procurement cycles promise to narrow the gap between user requirement definition and frontline delivery. Projects such as RAPSTONE and ASGARD are recent examples of how this approach can be done, alongside more deliberate (i.e. traditional) programme of record processes that continue at pace. Expanding these 'proven commercial routes' to deliver capabilities for units and formations that range from armoured platforms, ground-based sensors, communication suites and munition stocks is an exciting prospect. Equally promising is the DIS' pledge to "increase prototype warfare" as this directly relates to the Army's wholesale drive for Robotics and Autonomous Systems (RAS) integration at every echelon.

From a section operating with Uncrewed Ground Vehicles (UGVs) and Air Vehicles (UAS), to a formation headquarters that can plan and execute with AI-enabled battlefield analytics, this approach may see the transition from lab to field at unprecedented speed.

That said, whilst DIS 25 has been broadly welcomed for its ambition, there are concerns and criticisms surrounding DIS 25 it. Commentary at DSEI 25 revealed a persistent frustration among industry leaders regarding the MOD's pace of reform, particularly in contracting and capability delivery. Concerns were voiced about bureaucratic inertia and the slow translation of strategic ambition into executable contracts, with some firms publicly citing delays in the Land Mobility Programme (LMP) and uncertainty around the new medium helicopter programme as emblematic of systemic issues. In contrast, speeches by Defence Secretary...

Pride goeth before the fall

War starts with a bluster. Whether it is with sacrifices in the temples, parades or press conferences, young men are sent to battle with pomp and ceremony. Then, they storm the forts or the beaches or the hilltops. They die, usually horribly, foolishly, from mistakes historians will later describe as avoidable. Lessons are learned - often, they resemble lessoned already learned in previous conflicts. Force generation and employment adapts. War ends. Another one begins, the cycle repeats itself. Academics write about military incompetence; others wax poetically about zoology.

One could argue that this pattern was to be expected in the past. For the majority of human history, fighting was barely a profession and militaries were lean establishment. Modern staffs, the "brain of the army" were a very late invention. Beforehand, learning was personal, military scholarship (often surviving centuries, receiving a stature akin to holy scripture) was anecdotal and amateurish.

We have surely advanced since. Everywhere military "back office" has ballooned, the fighting force has been professionalized. Military academies were established and some places, education programs were even enshrined by law. The military profession has moved from mainly art to science and art.

Militaries started trying to design themselves for the next war, establishing bureaucracies and process that move vast resources for that purpose. Yet militaries seem to keep getting it wrong. For a recent example, one should look east, the Russia-Ukraine war. Prior to that conflict, the Russian military, on its face, did everything right - it had a robust and professional back office, with many educational facilities, granting advanced degrees in military art and science to officers serving many years in their positions. It undergone and extensive reform converting it from a heavy conscripted force to a lean semi-volunteer army. It modernized, introducing new kit in every service and branch. It had many experienced officers from recent conflicts from Chechnya to Georgia and Syria to Ukraine itself. It was, on the paper at least, a serious threat, a force to be reckoned with.

Yet, it too collapsed on the shores of reality and had to adapt and relearn lessons that were supposed to have already been known. This story is not unique. It repeats in many forms and languages. To the military professional observing from the ringside, this should raise serious questions about how militaries generate forces. Could it be that we are indeed incompetent? Are the tales of lions and donkeys true?

It is, of course, complicated

It is, indeed, complicated. Modern militaries like to engineer their forces. Force generation entails lengthy planning processes, involving many stakeholders and moving parts, over multiple years, meant to create the right force to win the first battle. To facilitate this design process, the military tries to holistically look at the various elements creating military power. These elements, referred to by the acronym DOTMLPF, describe everything that should go into the giant cocktail that is a military force - Doctrine, Organization, Training, Material, Leadership (and education), Personnel and Facilities. In recent years, a new ingredient was added to the recipe - Policy. With these powers combined, the right and lethel force is supposed to be created. This alphabet soup, however, only describes part of the very complicated picture and neglects the relationship between the various elements comprising military power. Depiction closer to reality would look something like this:

A military force is an organ (ideally) larger than the sum of its parts. These parts include "hard" elements (everything we can describe and measure), "soft" elements (other things we can't comfortably describe, but rather talk with more hand waving about), non-military elements and unknown variables. Analysts and pundits tend to focus on the "shiny objects" that a...

The United Kingdom's national resilience is a critical pillar of its security in an increasingly volatile global environment. As geopolitical tensions rise, particularly with adversaries such as Russia, the UK faces multifaceted threats that target its centres of gravity: key societal, economic, and infrastructural elements that underpin national stability. These centres include critical national infrastructure (CNI) such as telecommunications, water, energy, and social cohesion, which are vital to the functioning of modern society. In response to these threats, defence primes have advocated for investments in ground-based air defence (GBAD) systems, often citing Israel's Iron Dome as a model for protecting against missile and drone attacks. However, the UK's geopolitical and geographical context differs significantly from Israel, rendering direct comparisons problematic.

While GBAD systems have a role, they are not the primary solution to the UK's immediate threats, which are more likely to involve hybrid warfare, cyberattacks, and disruptions to CNI rather than conventional missile barrages. This essay examines the challenges to UK national resilience, the limitations of GBAD as a solution, recent events targeting UK vulnerabilities, and the broader strategies needed to bolster resilience within the NATO framework.

Understanding Centres of Gravity and UK Vulnerabilities

In military and strategic theory, centres of gravity are the critical capabilities or assets that, if disrupted, significantly weaken a nation's ability to function. For the UK, these include CNI (telecommunications, energy, water, and transport), economic stability, public trust, and social cohesion. Unlike traditional military targets such as bases or airfields, these centres are civilian in nature but essential to national security. Adversaries seeking to undermine the UK are increasingly likely to employ hybrid tactics - combining cyberattacks, disinformation, sabotage, and economic disruption - to destabilise these assets without resorting to direct military confrontation.

Recent events underscore the vulnerability of these centres. In 2024, reports indicated that the UK faces approximately 90,000 cyberattacks daily, many attributed to Russia and its allies, targeting government systems, financial institutions (FSI), and critical national infrastructure (CNI). These attacks aim to disrupt digital infrastructure, steal sensitive data, or sow distrust in institutions. Additionally, suspected sabotage of undersea cables in the Baltic Sea in 2024 highlighted the fragility of the UK's international communications networks, which are critical for economic and security functions. Such incidents demonstrate that adversaries prioritise non-kinetic means to degrade the UK's resilience, exploiting its reliance on interconnected systems.

The UK's population centres are also vulnerable to disruptions that do not involve missiles. Power cuts, for instance, could paralyse urban areas, disrupting healthcare, transport, and food supply chains. The 2019 UK power outages, though not attributed to hostile action, exposed how a single failure in the National Grid could affect millions, with hospitals and transport systems struggling to cope. Similarly, social media-inspired unrest, as seen in the 2011 London riots and more recently in Southport, illustrates how disinformation or orchestrated campaigns could amplify social tensions, undermining public order. These examples highlight that adversaries can achieve strategic goals by targeting civilian infrastructure and societal cohesion rather than military assets.

Defence Primes and the Push for GBAD Systems

Defence primes, such as MBDA and Northrop Grumman, have seized on the growing threat perception to advocate for enhanced air and missile defence systems, particularly GBAD. They point to Israel's Iron Dome, which has successfully intercepted short-range rockets and drones, as a case study for why the UK should invest i...

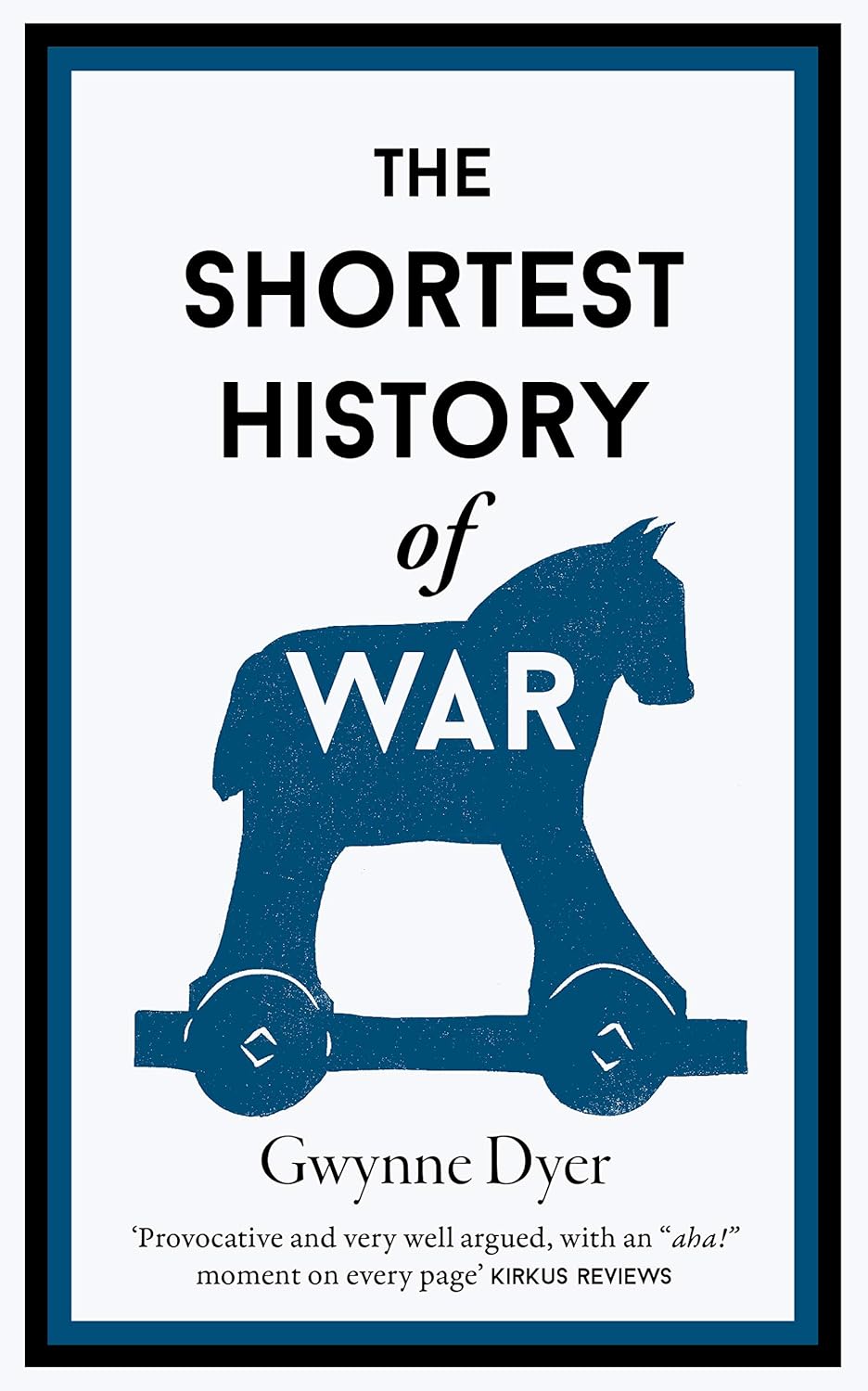

Why Short Histories Matter

War has long been the domain of soldiers and scholars: studied by the few, practised by the fewer, but suffered by the many. In the absence of lived memory, the risk is that societies forget what war really means.

This fading memory matters. The 20th century saw war reach its historical zenith through extreme industrialised conflict. It was a time of mass mobilisation, unprecedented global integration, and civilian populations on the front and rear lines like never before. But today, nearly a century later, no full generation left alive can truly compute the scale of destruction the first half of the 1900s wrought outside of study, media, or memory.

Total war is often abstract. It is reduced to historical footage, elevated by academic study, rendered across film and games, or reflected through anecdotes by those who have experienced conflict in our lifetime. That makes public understanding not just desirable, but necessary. As Great Power Competition returns, we risk confronting future war without a logical and emotional foundation needed to respect its costs.

That is the challenge Gwynne Dyer takes up in The Shortest History of War. If war must be made intelligible to the many and not just the few, then its complexity simplified is key. His message is clear: violence certainly exists in nature, and fighting is too common across the animal kingdom; but war is something distinctly human. It is an institutional practice born of hierarchy, sustained by coercion, and shaped by political purpose.

What the Book Gets Right: The Impressive Scope

Dyer's narrative unfolds in broad chronological arcs, but its power lies in rejecting determinism. War, he argues, has never been inevitable and has always been enabled. Elites choose it, institutions entrench it, and ideologies justify it.

Going as far back as historically plausible for a self-respecting scholar, Dyer systematically dismantles romantic myths of honourable violence and the noble savage. Instead, he traces how conflict has been shaped by degrees of industrialisation across millennia, various forms of nationalism before and after Westphalia was even a thing, evolving methods of bureaucracy long before Mandarins, and even game theory as a thought experiment.

These are forces, Dyer outlines, which rhyme across history, reinforcing the institutional logic of violence and escalating its lethality. War is not some immutable condition of humanity - it is a social technology. A political invention, forged in the surplus of early agriculture and sustained by organised power ever since.

One of the book's most striking passages illustrates the intense changes in just the last few centuries. Outlining the use of phalanx-style tactics, Dyer observes that a well-trained army from 1500 BCE (if rearmed with iron instead of bronze) could plausibly hold its own against one from 1500 CE. Yet within just a century of that, the military revolutions of the 17th century made such continuity impossible. The accelerating pace of change, particularly in our lifetime, has transformed war's destructiveness beyond recognition. Where war once meant hours of bloody attrition with swords or muskets, today it can mean a nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile capable of erasing cities in minutes. The gap between what war was and what it could become has never been wider.

Nowhere is this institutional absurdity clearer than in Dyer's analysis of Cold War nuclear doctrines. Mutually assured destruction (MAD), he writes, was not strategic brilliance but a global suicide pact rationalised into orthodoxy. What began as deterrence hardened into doctrine - a logic so widely accepted that he says its contradictions became invisible. But The Shortest History of War is not a book about tactics, doctrines, or battlefield dynamics. It is not concerned with how wars are fought, but why war became possible at all.

Dyer is philosophical as any other scholar of war, but he nonetheless br...

The views expressed in this Paper are the authors', and do not represent those of MOD, the Royal Navy, RNSSC, or any other institution.

The transformation of the UK's Commando Forces (CF), anchored in the Littoral Response Groups (LRGs) and the CF concept, represents an ambitious shift in British expeditionary warfare. However, its viability is undermined by structural and doctrinal disjoints that question its ability to operate effectively in contested littoral environments. Chief among these issues are: the persistent disconnect between the British Army and Royal Navy (RN); inconsistencies between UK Joint Theatre Entry Doctrine and emergent CF operational concepts; and the historical realities of military operations in littorals - especially the Baltic - which highlight the need for mass and endurance over rapid raiding.

The Army-Navy Disconnect: An Enduring Structural Weakness

CF transformation seeks to create an agile, distributed force capable of operating in complex littoral zones. However, its success is constrained by the systemic disconnect between the RN and Army. Despite their transformation into a high-readiness raiding force, the CF remains reliant on 17 Port and Maritime Regiment RLC (17P&M) for strategic lift and sustainment. Recent analysis underscores 17P&M's indispensable role in enabling amphibious operations, yet it is a relatively misunderstood, under-resourced, and neglected capability within the broader amphibious force structure, and one that remains firmly under an Army Op Order.1

The Army's focus on land-centric deterrence in Europe - particularly through the NATO Allied Rapid Reaction Corps and recently deployed Allied Reaction Force - suggests limited institutional buy-in for amphibious operations beyond logistical support. Ironically, it is the Army's reliance on 'red carpet' port-to-port transfer of forces that underpins its continental strategy, as evidenced in the seaborne deployment of 1UK Div to Romania via Greece2 and the recent signing of a 'strategic agreement' with Associated British Ports to expand staging options beyond Marchwood military port.3 This absence of a unified Army-Navy vision for expeditionary warfare leaves the UK in a precarious position: a CF designed for high-intensity littoral raiding, but dependent on an Army-enabled logistics structure that remains geared towards continental land warfare.

Similarly, the CF's raiding focus risks confusing the amphibious shipping requirement by ignoring the Army's need for logistical mass, as well as other doctrinally recognised amphibious operations such as Humanitarian Aid and Disaster Relief.[not

Doctrinal Incoherence: Joint Theatre Entry vs. Commando Force Operations

The UK's Joint Theatre Entry Doctrine emphasizes securing lodgements to facilitate force build-up and follow-on operations. Historically, this has required large-scale amphibious capabilities, pre-positioned logistics, and joint enablers. Yet, the emergent CF concept of operations prioritizes distributed, small-unit raiding without a clear pathway to sustained presence or operational endurance. This is accentuated by naval-centric command and control; the CF is a maritime force element composed of naval platforms and personnel optimised to support a maritime - rather than land - campaign plan.

Critiques of raiding highlights its fundamental limitations: it is resource-intensive, difficult to sustain, and often a tactic of operational necessity rather than strategic advantage.4 While raiding can disrupt adversary activity, it cannot replace force projection or control of key maritime terrain, both of which require relative mass and sustainment. By orienting the CF around raiding without a credible joint force integration plan, the UK risks investing in a force that is tactically innovative but strategically irrelevant.

Moreover, this raises a crucial question: if the UK's future amphibious posture is designed for raiding rather than securing and holding terrain, how d...

Incremental adaptation in modern warfare has astonished military observers globally. Ukraine's meticulously planned Operation Spider Web stands as a stark reminder of how bottom-up innovation combined with hi-tech solutions can prove their mettle on the battlefield. It has also exposed the recurring flaw in the strategic mindsets of the great powers: undermining small powers, their propensity for defence, and their will to resist. Having large-scale conventional militaries and legacy battle systems, great powers are generally guided by a hubris of technological preeminence and expectations of fighting large-scale industrial wars. In contrast, small powers don't fight in the same paradigm; they innovate from the bottom up, leveraging terrain advantage by repurposing dual-use tech, turning the asymmetries to their favour.

History offers notable instances of great power failures in asymmetric conflicts. From the French Peninsular War to the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, these conflicts demonstrate the great powers' failure to adapt to the opponent's asymmetric strategies. This is partly due to their infatuation with the homogeneity of military thought, overwhelming firepower and opponents' strategic circumspection to avoid symmetric confrontation with the great powers.

On the contrary, small powers possess limited means and objectives when confronting a great power. They simply avoid fighting in the opponent's favoured paradigm. Instead, they employ an indirect strategy of attrition, foster bottom-up high-tech innovation and leverage terrain knowledge to increase attritional cost and exhaust opponents' political will to fight. Similarly, small powers are often more resilient, which is manifested by their higher threshold of pain to incur losses, an aspect notably absent in great powers' war calculus.

In the Operation Spider Web, Ukraine employed a fusion of drone technology with human intelligence (HUMINT) to attack Russia's strategic aviation mainstays. Eighteen months before the attack, Ukraine's Security Services (SBU) covertly smuggled small drones and modular launch systems compartmentalised inside cargo trucks. These drones were later transported close to Russian airbases. Utilising an open-source software called ArduPilot, these drones struck a handful of Russia's rear defences, including Olenya, Ivanovo, Dyagilevo and Belaya airbases. Among these bases, Olenya is home to the 40th Composite Aviation Regiment - a guardian of Russia's strategic bomber fleet capable of conducting long-range strikes.

The operation not only damaged Russia's second-strike capability but also caught the Russian military off guard in anticipating such a coordinated strike in its strategic depth. Russia's rugged terrain, vast geography and harsh climate realities shielded its rear defences from foreign incursions. Nonetheless, Ukraine's bottom-up innovation in hi-tech solutions, coupled with a robust HUMINT network, enabled it to hit the strategic nerve centres, which remained geographically insulated for centuries.

Since the offset of hostilities, Ukraine has adopted a whole-of-society approach to enhance its defence and technological ecosystem. By leveraging creativity, Ukraine meticulously developed, tested and repurposed the dual-use technologies to maximise its warfighting potential. From sinking Russia's flagship Moskva to hitting its aviation backbones, Ukraine abridged the loop between prototyping, testing, and fielding drones in its force structures.

Another underrated aspect of Ukraine's success is the innovate or perish mindset. Russia's preponderant technology and overwhelming firepower prompted Ukrainians to find a rapid solution to defence production. Most of Ukraine's defence industrial base is located in Eastern Ukraine, which sustained millions of dollars' worth of damage from Russia's relentless assaults. Therefore, the Ukrainian government made incremental changes in Military Equipment and Weaponry (MEW) requirements by outs...

The United States Defence Secretary, Pete Hegseth, recently commented that the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan, which existed between 2001-2014, colloquially stood for 'I saw Americans fighting' at a recent Capitol hearing.1 Hegseth was giving evidence in front of the Senate Appropriations Committee when he made the comment, which complements the current Trump Administration's of America-First foreign policy,2 in that European countries should not rely on American military support and that Europe should be pulling its weight more in support of collective defence.

Hegseth further added that, 'what ultimately was a lot of flags, was not a lot of ground capability, you're not a real coalition unless you have real defense capabilities and real armies can bring those to bear and that's a reality Europe is waking up to quickly'.3 Senator Chris Coon, a Democrat who sat on the Committee, was quick to clarify that other military partners served and died within Afghanistan.4 In an unpredictable world this exchange provoked a key thought, what makes a good military coalition partner, seen from a Western perspective?

Brief History of Military Coalitions

Forming military coalitions based on shared strategic goals is not a new concept. Pragmatically, it makes sense to form military coalitions to share capabilities/equipment, to act as a deterrence, and to form international legitimacy against any action against a common adversary. Even the mighty Spartan Army fought alongside a military alliance with other Greek soldiers when threatened by the Persian Empire in the 5th Century BCE. According to Herodotus, there were only 300 Spartan Royal bodyguards in comparison to thousands of other Greeks who fought against the Persians.5 However, these Spartans were portrayed as warriors who were disciplined and highly trained in comparison to other Greek soldiers.6 Facing a force of a hundred thousand Persian soldiers, the odds were against the Greeks.

Were the Spartans a better coalition partner than the other Greeks as they had alleged quality over quantity, or was mass required? The eventual defeat of the Greeks at the Battle of Thermopylae and sacking of Athens, perhaps for this specific battle, meant that simply more Greeks were needed to match the Persians.

Moving forward to the 21st Century, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) was created in 1949. ISAF was formed after the events of 9/11, when Article 5 was triggered, but it was in 2003 when NATO took the lead of the UN mission in Afghanistan. At the height of the mission, 51 NATO and partner nations provided troops.7 With six different ISAF objectives and the whole of Afghanistan divided into five (later six in 2010) Regional Commands, ISAF members held various roles and responsibilities. For example, Regional Command North was commanded by Germany with troops from Sweden, Hungary, and Norway supporting the various missions.8 Troop numbers and equipment supplied varied across ISAF, with the United States contributing the most significant number of troops by some margin.

This tragically resulted in greater deaths, with the United States losing nearly 2500 military personnel in comparison to a country like Georgia, in which 29 military personnel were killed.9 When compared against the population size of Georgia (a non-NATO country), the deaths experienced in Afghanistan resulted in a death per million rating of 8.42, higher than the United States at 7.96. However, it is ethically challenging to compare the number of casualties experienced by each partner. As such, measuring casualty figures by each coalition partner is not an efficient way to determine if each country is 'pulling its weight'.

Another significant military coalition was formed in 2014. The Global Coalition against Daesh originally had 13 members, but today has 87 partners and is designed to degrade and ensure Daesh's enduring defeat.10 In September 2014, President Obama commented in a majo...

Europe's NATO members can gain an operational advantage by reframing close-combat training. However, with the current Combatives models, this change would add burden to both time-in-training and financial resources. Seizing this opportunity would require replacing the current technique/MMA-based models with a leaner model. To this end, alternative options offer increased functional expertise and substantial reductions in time and cost allocations.

To demonstrate this, we can use "time-in-training" to compare costs-and-time allotments against the achieved level of functional expertise.

The technique-based models:

For this comparison, the U.S. Army's current MMA-based Combatives training-model is a well-documented program. Here, 40-hours of training produces a "questionable" level-1 proficiency. An additional 80-hours produces a Level 2 proficiency. A combined total of 440-hours achieves the top level-4 proficiency. However, the average U.S. soldier only holds a level-1 or level-2 rating.

The statement of "questionable" proficiency is founded in the comparison of four scientific points;

1. Developing functional expertise: Functional expertise in MMA techniques require extensive repetition.

2500 to 3000 repetitions of technique are required to create the most basic mental-map (muscle-memory). This requirement increases with complexity. MMA techniques are complex. For example - Level 1 has a minimum of 8 phases, each with multiple individual techniques. Achieving basic functionality in any one phase equals 2500 times the number of techniques it contains.

1. Situational Awareness and Avoidance

2. Stress Management and Decision Making

3. Dominant Body Positions, range & range transitions, and body control, (a key principle)

4. Basic striking and defensive techniques

5. Grappling, throws, takedowns, clinch, chokes, and knee defense

6. Introductory rifle/knife based Combatives

7. Techniques for creating distance and disengaging from an opponent

8. Realistic Training and Application

2. Retention of functional expertise: Retention of functional expertise in complex techniques is low.

Retention of a complex movements (effective expertise) depends on repetitions and the time since last practiced. The factors listed below negatively affect retention.

1. How natural the movement is - Generally MMA techniques are not natural movements.

2. The complexity of the movement - Generally MMA techniques are complex.

3. The frequency between initial-training and recurrent training - MMA requires high frequencies.

3. The deterioration of fine movement under stress: MMA methods include fine-motor techniques.

High psychological/physiological stresses cause fine-motor deterioration. Deterioration begins at 145 heart-rate (BPM). The more complex a movement is, the more it deteriorates.

4. Somatic-markers: Somatic-markers determine access to mental-maps (techniques).

"Somatic-markers" store, sort, and select physical movement. Somatic-markers use rapid-sorting to determine selection. The most practised mental-maps are the quickest; lesser used maps are slower.

As counter-point, I am well versed in W.E. Fairbairn's "Gutter Fighting", so I will speak from that as an alternate option. In comparison with the MMA model, Gutter Fighting's battle-proven model achieves a higher-than-average functionality in less than 40- hours.

Completing the U.S.'s level-1 and 2 models will require 120-hours; completing the Gutter Fighting model will require 40-hours. 80-hours is a massive time/cost reduction. These savings will repeat every time the program is run. These are time/cost saving that can be reallocated to greater advantage elsewhere. Conversely, the MMA model repeats their double-rate-loss every time its program is run.

The Gutter Fighting Variant:

1. Developing functional expertise: Principle-based, Gutter Fighting is very natural.

Training installs a small toolbox of techniques that personally fit the user. This natural ease-of-execution accelerates efficiency,...

The recently published Strategic Defence Review (SDR)1 and National Security Strategy (NSS)2 both place accelerating development and adoption of automation and Artificial Intelligence (AI) at the heart of their bold new vision for Defence.

I've written elsewhere3 about the broader ethical implications,4 but want here to turn attention to the 'so what?', and particularly the 'now what?' Specifically, I'd like to explore a question SDR itself raises, of "Artificial Intelligence and autonomy reach[ing] the necessary levels of capability and trust" (emphasis added). What do we actually mean by this, what is the risk, and how might we go about addressing it?

The proliferation of AI, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), promises a revolution in efficiency and analytical capability.5 For Defence, the allure of leveraging AI to accelerate the 'OODA loop' (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) and maintain decision advantage is undeniable.

Yet, as the use of these tools becomes more widespread, a peculiar and potentially hazardous flaw is becoming increasingly and undeniably apparent: their propensity to 'hallucinate' - to generate plausible, confident, yet entirely fabricated and, importantly, false information.6 The resulting 'botshit'7 presents a novel technical, and ethical, challenge.

It also finds a powerful and troubling analogue in a problem that has long plagued hierarchical organisations, and which UK Defence has particularly wrestled with: the human tendency for subordinates to tell their superiors what they believe those superiors want to hear.8 Of particular concern in this context, this latter does not necessarily trouble itself with whether that report is true or not, merely that it is what is felt to be required; such 'bullshit'9 10 is thus subtly but importantly

different from 'lying', and seemingly more akin therefore to its digital cousin.

I argue however that while 'botshit' and 'bullshit' produce deceptively similar outputs - confidently delivered, seemingly authoritative falsehoods, that arise not from aversion to the truth, but (relative) indifference to it, and that may corrupt judgement - their underlying causes, and therefore their respective treatments, are fundamentally different. Indeed, this distinction was demonstrated with startling clarity during the research for this very paper.