Discover The NewCrits Podcast

The NewCrits Podcast

The NewCrits Podcast

The NewCrits Podcast

Author: with Ajay Kurian

Subscribed: 3Played: 14Subscribe

Share

© Ajay Kurian

Description

Interviews with Artists where we talk about their work, their life, and the world around them.

newcrits.substack.com

newcrits.substack.com

15 Episodes

Reverse

A BDSM dungeon for alchemist Bitcoin investors. A druid hideaway in the abandoned Palo Alto headquarters of the corporation Theranos. A crossover between Breaking Bad and Game of Thrones where Walter White cooks meth for White Walkers. These are some of the images that Elaine’s work conjures up for people. In this case, the writer and art historian Colby Chamberlain. I like to look at Elaine’s work thinking about the shifts in difference between visual prose and visual poetry. There are narratives, ideas, concepts, but there’s also evocations, atmospherics, and rhythms that key you in as well. spite the notable iciness from some of the work, you can still sense a beating heart. It’s the reason I return to the work and get excited for new shows of hers. There’s a feeling of the post apocalyptic, a sense of dread, there’s violence and the vestiges of religion, but from the way these works come together and how each show operates, I get the sense that this is a person wrestling with belief, not someone who’s already sworn it off. And it’s those struggles that I’m interested in. Why do any of us fight the fights we do? And what does it say about us?In this conversation, we discuss:* Early post-art school experimentation and resourcefulness* Technical training in metal, glass, and ceramics* Moving to New York and formative professional relationships* Brass, aluminum, and the scientific aura of materials* Religion, ritual, and the outsider gaze* Modularity and impermanence in installation* Military artifacts and the aesthetics of violence* Cultural archetypes and embodied identity* Writing as a parallel conceptual practice* Readymades, relics, and inherited material memory* The artist as conduit and criticTimestamps(0:00) Introduction and Framing the Conversation(5:00) Early Career and Technical Training in Alberta(14:00) Moving to New York and Early Gallery Relationships(19:00) Material Exploration: Brass, Aluminum, and Process(25:00) Ritual, Religion, and Cultural Observation(31:00) Modularity and Impermanent Installation(39:00) Military Artifacts, Violence, and Political Aesthetics(45:00) Archetypes, Identity, and Cultural Tropes(52:00) Writing, Language, and Reflection(57:00) Readymades, Relics, and Object Memory(1:00:00) Conduit vs. Critique: Final ReflectionsWatch the conversationView the full episode on YouTube.Follow Elainehttp://lissongallery.com/artists/elaine-cameron-weirElaine Cameron-Weir was born in 1985 in Red Deer, Alberta, Canada; she lives and works in New York. Past solo exhibitions at institutions include: Dressing for Windows (Exploded View), SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, USA (2022); STAR CLUB REDEMPTION BOOTH, Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, USA (2021); exhibit from a dripping personal collection, Dortmunder Kunstverein, Dortmund, Germany (2018); Outlooks, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, USA (2018) and viscera has questions about itself, New Museum, New York, USA (2017). Her work has featured in major group exhibitions including The Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani at the 59th Venice Biennale, Italy (2022); New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century, BAMPFA, Berkeley, USA (2021); Present Tense, Philadelphia Museum of Art, USA (2019), as well as the Belgrade Biennale, Serbia (2021); the Montreal Biennial, Canada (2017) and the Fellbach Triennial of Small-Scale Sculpture, Germany (2016).About The ForumThe Forum is NewCrits’ ongoing public talk series, presented in partnership with WSA/WSBS. Talks take place live every second Tuesday at WSA. Join us for our next conversation here.Explore NewCrits’ offerings, including crits, courses, and mentorship programs at www.newcrits.studio.—Full TranscriptAjay Kurian: I've always loved your work, and there was a specific moment in 2014, at Ramiken Crucible, where I was genuinely floored.It was so quiet in there. It was so beautiful and eerie. The scent in the air, everything about it felt meticulous but also carefree. It wasn't overly theatrical or overdone.And I just want to start from the beginning, because there's an arc of the visual poetry that you start making and it would be interesting for me to understand how certain things started to congeal, how certain sculptural forms started to congeal for you. This is the first show that you did at Ramekin Crucible in 2011 called “without true bazaars”. Do you even remember this show?Elaine Cameron-Weir: Yeah, it's interesting to see it. It was so long ago.Ajay Kurian: Fourteen years.Elaine Cameron-Weir: When I see these images, I immediately think about how I had no money, and was really just working with what I could get my hands on.But, you know, that wasn't an obstacle at the time. It was normal. But looking back, the simplicity of what I was doing and the type of materials…I mean, it doesn't feel like student work, but because I was just out of school, I was so young, and I wasn't fully formed, it still feels transitional. But it was a such an opportunity to learn about what I was doing in public, and it could have goneAjay Kurian: I feel like first solo shows, it's like you have nothing to lose. So it's just like, fuck it, do what you want to do.Elaine Cameron-Weir: And limited resources, so you can't just go crazy - you’re contained.Ajay Kurian: What was before this? Were you in art schoolElaine Cameron-Weir: Yes. I'm from Canada and I grew up in Alberta. It's like the Texas of Canada, if you're not familiar. Yeah. above Montana, but I went to Art School right out of high school. It's way less of a commitment there because it's so cheap. It's not like a fraught decision. Like should I spend all this money to go to art school? It's like, try it.Ajay Kurian: So that was a BFA program?Elaine Cameron-Weir: Yes, at the Alberta College of Art. They had amazing, world class facilities. So I actually learned how to do very niche metalworking. They had a glass blowing shop, ceramics; you could cast bronze there. So I got a really technical education. I was in the drawing department, and we had to go draw cadavers at the hospital. But then there were really good instructors as well where it was really their mission to teach and they were really good at making you think about what you're doing.And then I graduated from there and I didn't really know what to do. I was working at American Apparel and the rents were getting jacked up in Calgary where the school was because there was an oil boom going on. I had to leave. So I moved back in with my dad And I turned his garage into a studio.And I hated it there so much. It's the small city that I went to high school in. so I immediately applied to grad school in New York without knowing anything about any school in New York. I just did a quick search and I was like, okay, we're going to just apply to all of these and get out of here.And that's how I ended up in New York. I went to NYU. I graduated in 2010.Ajay Kurian: Okay. when did you meet Mike? Mike is the owner of Ramekin Crucible.Elaine Cameron-Weir: I don't know what year, probably 2010 or 11, at a party. At the Jane Hotel.Ajay Kurian: It's so interesting to hear about those early conversations with your first gallerist because there's so much history that happens in that moment and then looking back on it retrospectively you're like wow what was that?Elaine Cameron-Weir: I think we were both learning a lot, you know? And we took a chance on each other. It sounds crazy now, like we met at a party, but that's how you used to meet people. And we had mutual friends, like Borden, Capalino. So we met at this party, and we got to talking and then a studio visit with him and Blaize (Lehane, former director at Ramiken Crucible). The building I was living in had just caught fire right before the visit. A lot was going on for me personally, but it ended up working out really well because I didn't have to pay rent for like six months, which is one of the reasons I could stay in New York. The work I was making, was similar to what I made for that first show.I think I made this piece actually in school, that long stick thing. it's just a piece of MDF, or maybe it's actual wood. It was coated in a pouch of rolling tobacco. I think that piece was in my grad show at NYU.Ajay Kurian: I'm gonna skip to the next show. This is the first time, you start using brass in the work. It sounds like you already had a decent understanding of, how to make almost anything based on your education. These brass leaves - did you make those yourself? Was that outsourced? How did that happen?Elaine Cameron-Weir: No, I made it all. Except the piece of those, cast aluminum things at the top. You can't tell what they are, but I made those with my dad in Canada.Ajay Kurian: What are they? I remember seeing, there's been a couple of iterations of them. I remember seeing them here. I remember seeing them at an art fair where the whole booth was filled with almost like a rhythm of these, for the lack of a better word, “blanks.” Do you consider them kind of blanks or what are they made out of?Elaine Cameron-Weir: Yeah, I was kind of thinking about an ingot, which is like a cast piece of metal And a photographic plate or a blank. I used to go, I still go to the NYU library and they had amazing books from NASA there. They had this great atlas of photographs of the moon, like before they went to the moon. the photographic technique is done in scans, so it's kind of like stripes. the book is large and you can flip it.And each page - I was kind of thinking each as sort of like a page from that book - it was like plotting something in the round into a flatness.Ajay Kurian: Scale-wise, they’re almost like a oversized book.Elaine Cameron-Weir: Yeah, that's the reason for the scale, something that you could potentially hold. And then they're on this rail, because they don't actually hang on the wall. They're always meant to sit on something and lean. So they're like an object, they don't have a thing on the back that you can stick them on the wall.Aj

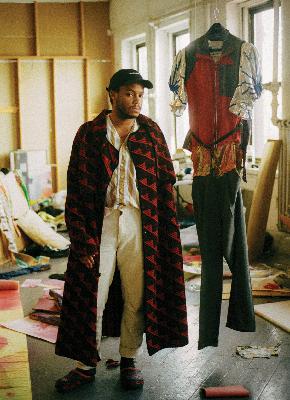

I met Steve this past summer at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, where we were both resident faculty members. I quickly fell in love with his wit (biting), his work (also biting), and his tenderness (much less biting). In our conversation here, we cover his first experience with an artwork, his relationship to portraiture, and the origins of Modernism in the auction block.He’s unabashed in his distaste for prioritizing personal hardship to make art. In his own words, “This idea that we’re going to get together and have a party for our pain, and somehow art is gonna come out of that..? No, baby, you better go to an observational drawing class.” Regardless of whether you agree with Steve’s perspectives, listening to him tell it is thoroughly enjoyable.In this conversation, we discuss:* Early encounters with art and the emotional force of seeing Van Gogh* Art as both repression and a space for self-discovery* The role of gesture and ambiguity in figurative work* Studio practice, community, and artistic solitude* Grief, loss, and the logic of the grid paintings* Public art as social intervention* Modernism, slavery, and cultural inheritance* Pain, performance, and artistic expressionTimestamps(0:00) Introduction and Background: Mass MoCA and Early Context(2:00) Early Influences: Detroit Institute of Arts and Van Gogh(6:00) Art School and the Turn to Portrait Painting(10:00) Art as Repression and Safe Space(27:00) Artistic Community: Skowhegan and Boston(30:00) Craft, Memory, and Sculptural Expansion(36:00) Grief, Communication, and the Grid Paintings(47:00) Public Art: “Three Deliberate Grays for Freddie”(50:00) “Homage to the Auction Block” and Modernism (55:00) Pain, Performance, and Shared Experience (1:04:00) Audience Q&AWatch the conversationView the full episode on YouTube.Follow Stevehttps://www.stevelocke.com/https://www.instagram.com/svlocke/?hl=enSteve Locke (b.1963, Cleveland, OH) lives and works in the Hudson Valley, NY. He received his MFA from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 2001. Spanning painting, drawing, sculpture, and installation, Locke’s practice critically engages with the Western canon to muse on the connections between desire, identity, and violence. Locke’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Moss Arts Center at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg (2022); The Gallatin Galleries, New York University, NY (2019); Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA (2018); among others. He has participated in group exhibitions at the Green Family Art Foundation, Dallas, TX (2023); MassArt Art Museum (MAAM), Boston, MA (2023); Jack Shainman Gallery, Kinderhook, NY (2021); Fitchburg Art Museum, MA (2020); Fruitlands Museum, Harvard, MA (2020); Boston Center for the Arts, MA (2018); Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (2018); among many others.About The ForumThe Forum is NewCrits’ ongoing public talk series, presented in partnership with WSA/WSBS. Talks take place live every second Tuesday at WSA. Join us for our next conversationhere.Explore NewCrits’ offerings, including crits, courses, and mentorship programs atwww.newcrits.studio.—Full TranscriptComing Soon. Get full access to NewCrits Substack at newcrits.substack.com/subscribe

Jamian Juliano-Villani was born in 1987 in Newark, New Jersey, and lives and works in New York. As the daughter of commercial silkscreen printers, she spent time as a child working in her parents’ factory, folding more than four thousand Pope John Paul II T-shirts in ninety-seven-degree heat while absorbing the influence of 1990s and 2000s mass-market print design. She attended the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, New Jersey, graduating with a BFA. While there, she was influenced by the institution’s historic ties to Fluxus, her studies with John Yau and Raphael Ortiz, and the Zimmerli Art Museum’s collection of 1970s Soviet conceptual painting.She’s in the collection of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, and the Louis Vuitton Foundation, among others.In this conversation, we discuss:* Growing up in a family rooted in advertising and printing, and how that shaped but did not determine her artistic path* Painting as a series of formal problems to solve, grounded in decision-making and restraint* Collaboration as an ongoing negotiation, including disagreement, silence, and repair* The relationship between politics and art, and the limits of political messaging in painting* Influences, including Ralph Bakshi and Christian Ludwig Attersee, and how past experiences inform her current work* The role of community and collective projects like The PatriotTimestamps(12:26) Family and Artistic Influence(19:16) Problem-Solving and Formal Challenges(25:00) Collaboration and Dialogue in Art(31:00) Political Messages in Artwork and Creative Freedoms(38:00) Collaboration and CommunityWatch the conversationView the full episode on YouTube.Follow Jamianhttps://gagosian.com/artists/jamian-juliano-villani/https://www.instagram.com/psychojonkanoo/?hl=enCombining an affection for the full breadth of contemporary visual culture with an informed awareness of representational painting’s lengthy history, Jamian Juliano-Villani draws on a vast spectrum of references to produce uncanny and evocative images.Juliano-Villani was born in 1987 in Newark, New Jersey, and lives and works in New York. As the daughter of commercial silkscreen printers, she spent time as a child working in her parents’ factory, folding more than four thousand Pope John Paul II T-shirts in ninety-seven-degree heat while absorbing the influence of 1990s and 2000s mass-market print design. She attended the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, New Jersey, graduating with a BFA. While there, she was influenced by the institution’s historic ties to Fluxus, her studies with John Yau and Raphael Ortiz, and the Zimmerli Art Museum’s collection of 1970s Soviet conceptual painting.In 2013, Juliano-Villani presented her first solo exhibition, Me, Myself and Jah, at Rawson Projects, New York, showing paintings that incorporate characters from Ralph Bakshi’s film Cool World (1992). These works explore themes of race, identity, appropriation, and—in canvases such as Heat Wave (2013)—the collapsing of painterly hierarchies, while revealing the artist’s burgeoning admiration for the democratic nature of cartoons.About The ForumThe Forum is NewCrits’ ongoing public talk series, presented in partnership with WSA/WSBS. Talks take place live every second Tuesday at WSA. Join us for our next conversationhere.Explore NewCrits’ offerings, including crits, courses, and mentorship programs atwww.newcrits.studio. Get full access to NewCrits Substack at newcrits.substack.com/subscribe

Ser Serpas was born in 1995 in Los Angeles, California and lives and works in New York. Primarily interested in death and legacy, her work is preoccupied with its own urgency in the face of fossilization. At present, she’s taken to sequestering the mundane. Serpas’ work takes the form of unstable assemblages of found objects in which painting, sculpture, drawing, and text bring together personal memories and traces of everyday life. She mashes bits of her life, both real and imagined, into anti-portraits. Some of which she deems fit to share within the context of exhibitions and performances. Precarious assemblages of disparate objects found in the street, which bear the mark of their uses, constitute her most well-known series to date. More recently, she has taken to using photos shot on her iPhone during college as source material for intimate views on unstretched canvas, wood panel, and paper. The unique way she reframes the body and tension in both her sculptural and text-based installations, which distort components of our shared architecture, carries into her atypically cropped portions of stolen archetypical intimacy.In this conversation, we discuss:* Urgency, fossilization, and building work from ruin rather than permanence* Waste as imprint and the ethics of collecting discarded objects* Horror and discomfort as formal strategies* The aesthetics of survival* Training AI to hallucinate bodies* Control, labor, autonomy, and designing your lifeTimestamps(02:22) “Monakhos” and the ghosts inside the frame(07:30) The Collector: absence, imprint, and waste(15:51) Confidence is knowing when to stop(17:46) Training AI to hallucinate bodies(30:38) Ruined objects, ruined selves(35:00) The aesthetics of survival(48:20) Horror, unreason, and the art of discomfort(55:00) Control, labor, and designing your lifeWatch the conversationView the full episode on YouTube.Follow SerWeb: https://maxwellgraham.biz/artists/ser.Instagram: @ser_seraSer Serpas (b. 1995, Los Angeles, CA, USA, lives and works in Paris) Primarily interested in death and legacy, her work is preoccupied with its own urgency in the face of fossilization. At the present, she’s taken to sequestering the mundane while freely quoting art history in its full depth, paying little heed to the latter. Ser Serpa works take the from of unstable assemblages of found objects, in which painting, sculpture, drawing, and texts bring together personal memories and traces of everyday life. She mashes bits of her life, both real and imagined, into anti portraits, some of which she deems fit to share within the contexts of exhibitions and performances. Precarious assemblages of disparate objects found in the street, which bear the mark of their uses, constitute her most well known series to date. More recently she has taken to using photos shot on her iPhone during college as source material for intimate views on unstretched canvas, wood panel and paper. The unique way she reframes the body in tension, in both her sculptural and text based installations which distort components of our shared architecture, carries into her atypically cropped portions of stolen archetypal intimacy.About The ForumThe Forum is NewCrits’ ongoing public talk series, presented in partnership with WSA/WSBS. Talks take place live every second Tuesday at WSA. Join us for our next conversation here.Explore NewCrits’ offerings, including crits, courses, and mentorship programs at www.newcrits.studio.—Full TranscriptComing Soon. Get full access to NewCrits Substack at newcrits.substack.com/subscribe

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr is an artist who uses photography to explore representation through privacy and fiction. Sometimes his images work towards the mysteries a person can hold. Other times, they might explore the tension created through juxtapositions, or wisps of narrative and context, leaning further into abstraction. Altogether, his work foregrounds the possibilities and problems of photography today. In this conversation, we discuss: * Elvis Costello's "Green Shirt" and "emotional fascism"* Negotiating Identity in Photography* Collaborations with Solange and Telfar* Going for the "difficult" image instead of the "iconic" one* Abstraction through rupturing representation* Moving past racial cliches, even the new ones!Timestamps(0:00) Introduction and Song Selection: Elvis Costello’s Song “Green Shirt”(8:00) Shift in Artistic Perspective(11:45) Religion and Photography(20:00) Titles, Photography, and Collaboration(28:00) The “Dummy Image”(31:00) Navigating Internal Resistances in Photography Assignments(37:46) Representation vs. Abstraction in Photography(42:56) Influence of Deana Lawson and Critiques of Curatorial Frameworks(55:53) Audience Questions and Further DiscussionWatch the conversationView the full episode on YouTube.Follow ElliotWeb: https://elliottjeromebrownjr.com/Instagram: @elliottjeromebrownjrElliott Jerome Brown Jr. (b. 1993) lives and works in New York. He received his BFA in Photography from the Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. He has had solo exhibitions at Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York (2022, 2019); Staple Goods, New Orleans (2019) and Baxter St. at the Camera Club of New York (2019). Recent group exhibitions include Swiss Institute, New York (2021); RISD Museum of Art, Providence (2021); The Arts Club of Chicago (2020); New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans (2020); Public Art Fund, New York (2020); The MAC, Belfast (2019); PPOW, New York (2019); Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (2018); Yossi Milo Gallery, New York (2018); Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York (2018); We Buy Gold, New York (2018), among others. Recent museum acquisitions include the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York.About The ForumThe Forum is NewCrits’ ongoing public talk series, presented in partnership with WSA/WSBS. Talks take place live every second Tuesday at WSA. Join us for our next conversation here.Explore NewCrits’ offerings, including crits, courses, and mentorship programs at www.newcrits.studio.Full TranscriptComing Soon. Get full access to NewCrits Substack at newcrits.substack.com/subscribe

When David Zwirner approached Ebony L. Haynes, the conversation didn’t begin with vision statements or prestige. It began with reality: exhaustion, uncertainty, and the question of whether staying in the art world was even possible. What followed was recalibration. If she was going to continue, it had to be on terms that reflected how she actually works—through care, risk, and sustained presence. That recalibration became 52 Walker.Drawing from her time at Martos Gallery and its project space Shoot the Lobster, Haynes speaks candidly about what it means to build exhibitions from the ground up: buying furniture on credit cards, drilling into gallery floors, maintaining impossible works by hand, and staying late because the work deserves it. For her, autonomy is not branding or independence for its own sake. It is the ability to stay present with artists, to hold risk without spectacle, and to let rigor coexist with joy.Rather than framing curatorial work as management or authorship, Haynes describes it as a practice shaped by trust, repetition, and care—one that resists burnout not by slowing ambition, but by rooting it in pleasure, responsibility, and belief.She explains:* How Foxy Production taught her to do every job herself, and why learning the whole system changed how she values labor.* Why belief in the work often comes before money, and what it costs to act on that belief anyway.* How maintenance, repetition, and care are not secondary tasks but central to exhibition-making.* What quarantine, racial reckoning, and institutional fatigue revealed about her limits—and her resolve.* How 52 Walker emerged not from a master plan, but from presence, honesty, and the willingness to say, “I have this idea.”Timestamps(0:00) First Encounter and the Permission to Care(4:00) Foxy Production and Learning by Doing(7:00) Installation as Commitment(16:00) Belief, Debt, and the Couch(18:00) Maintenance, Repetition, and Joy(21:00) Quarantine, Burnout, and Almost Leaving(25:00) Martos Gallery and the Small Fish Problem(27:00) Shoot the Lobster and Experimental Freedom(32:00) 52 Walker and Building a Program(41:00) Artists, Power, and Staying in the WorkWatch the conversationView the full episode on YouTube.Follow EbonyInstagram: @ebotronFollow 52 WalkerWeb: https://www.52walker.com/Instagram: @52walker Writer, curator, and phenom Ebony L. Haynes is on a mission to reconfigure the art world. Working her way up from her first New York City internship at contemporary gallery Foxy Production (then based in Chelsea), the Canadian-born Haynes would eventually become the director of Marts Gallery and its project space Shoot the Lobster. In early 2020, Haynes was approached by David Zwirner for a sales director position. She countered with a pitch for an exhibition model resembling a kunsthalle, wherein exhibitions would last 3 months and allow for visitors to spend more time truly considering the art before them. That idea led to the October 2021 opening of 52 Walker, David Zwirner Gallery's TriBeCa location, with Haynes at the helm as director. Unlike traditional commercial galleries, 52 Walker does not represent artists, and is instead dedicated to curating programming at a pace similar to that of a museum — giving artists more opportunity to challenge themselves and experiment freely. The recruitment of an all-Black staff at 52 Walker garnered disproportionate attention, but her two-pronged approach to catalyzing change in the art world is more far-sighted than mere identity politics. In challenging the ever-shrinking attention spans of a cultural milieu that increasingly consumes art through social media, Haynes aims to empower artists to take risks and dig deeper in their work.About The ForumThe Forum is NewCrits’ ongoing public talk series, presented in partnership with WSA/WSBS. Talks take place live every second Tuesday at WSA. Join us for our next conversation here.Explore NewCrits’ offerings, including crits, courses, and mentorship programs at www.newcrits.studio.Full TranscriptAjay Kurian: What does it feel like to watch this right now?Ebony L. Haynes: You know, I haven’t watched this in a while. It stands so clear in my mind. The first time I experienced this artwork of perfection…Ajay Kurian: This was what I read and gathered was the first art experience where you were really rocked to your core.Ebony L. Haynes: There was a small space run by this formidable woman, Ydessa Hendeles in Toronto, who at the time I knew nothing about. I stumbled into this space based on some kind of art map. I was emotional, I remember crying the first time. I went back at least a half dozen times and it made me feel like pursuing something in the art world could really mean something.It was the very first artwork I ever remember feeling like this shit hits and there are so many layers to it. The first time I walked in, I didn’t know who Shirin Neshat was, you know? And it’ll be one of my opuses. I already had one. I thought Gordon Mata Clark and Pope.L is a show I did, and I’m like, oh, I can’t top it.But working closely with this artist and something around this work would be the next major emotional insurmountable moment for me. You have to visualize this two-channel video, before I knew what two-channel really meant. You know, I don’t wanna pretend like I was encountering this work and I knew all of the ways to talk about it.I walked into the room, and there were two screens. This window was a screen and the wall facing each other. So these performers are essentially facing each other and you’re sitting in the center. It was a purple carpet, very well installed. I come from a music background, so immediately I was like, the sound design was impeccable. Somebody really thought about six channels of sound and knew how to put the subwoofers in the right place to make me feel it when it hits that note. I was like crying for this woman. And also feeling a little bit for the man and I mean, it was…Ajay Kurian: There’s layers.Ebony L. Haynes: There’s layers. It’ll be a chapter. Yeah, it was huge for me.Ajay Kurian: It’s also such a different experience. Because I was watching this on my laptop and I was like, this is crazy. Then hearing it here, the hair on the back of my neck went…Ebony L. Haynes: Yeah when you see it, it was floor to ceiling, so it was larger than life bodies belting in front of me. I almost felt like I could feel the air out of the speakers. I mean, I was also there alone every time I went.Ajay Kurian: Wow. So this clocks as one of the formative experiences a hundred percent. In your sort of art upbringing, I’m gonna fast forward a little bit to when you actually make it to New York. Is your first job in the art world interning at Foxy?Ebony L. Haynes: Intern at Foxy Production, yep. Whenever I’m about to talk about Michael and John, Michael, Gillespie, John Thompson. I make it sound like we are really good friends and I hope we are, but we don’t text and call each other.But they know how important they were and are to my story. Foxy production was one I wrote to because of their program. I felt somebody, who at the moment when I applied, had worked in music mostly and that was my only full-time experience and writing about music. They were really kind of schmutzy and unmastered is what I remember saying to John in my letter. It was like this underground basement, party of a gallery where they were doing a lot of new media before many galleries. Maybe not. You know, I don’t know, but from my perspective.Ajay Kurian: They have that reputation, yeah.Ebony L. Haynes: So I just wrote them a letter and I was like, do you want me, I’d love to come and work for you for free. And they were like, cool, come on down. I did, and it was life-changing. I really expected it to be an internship where I go back and get a job in Toronto and it turned into a job for them.Ajay Kurian: And that’s when we met.Ebony L. Haynes: That’s when we met, so many years ago. That was 2012, I think. Something like that.Ajay Kurian: With people that are in the gallery world or in the commercial art world — my gallerist for instance, Oliver, he worked for Alexander and Bonin. And he really credits them as being the ones who really gave him his grounding and his understanding of what it meant to be a gallerist. Do you feel similarly? You worked at Foxy, then you worked at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, then you worked at Martos. Of those three experiences, what has felt like the one that’s grounded you the most?Ebony L. Haynes: Grounded me, probably Martos. You know, Martos and Shoot The Lobster. I have to say both because I was tasked to program three galleries bicoastally at the same time with a staff of one.Ajay Kurian: That’s insane.Ebony L. Haynes: Sometimes an intern or assistant, eventually it grew, but it took years. Foxy though, made me really appreciate what it means to learn everything about my job. They taught me how to make an invoice, what a performer was for shipping, what the difference between national and international crates are, and how to hang an art fair booth. Registrars and production art handling are my complete IV lifeblood. If my registrar and my art handlers are not happy… I’m the queen of Donuts install morning or let’s get some pizza. When it was Martos time, I’d do some beer after hours, but not at David Zwirner. Because. I remember one story, this show at Martos, Invisible Man. Pope.L created a new work for me and it was a fountain that hung upside down. I’d hired an art handling and production company to help me build that plinth and figure out how to hang it safely and successfully from the beam. No shade, in case anybody is associated with that experience, and much love to the crew. But they bailed before it was hung. They claimed, and to their credit I think it was hard, but they just were not gonna be responsible for it.So I had to figure out how to rent scaffolding and enlist somebody, who I’m thankful is now a partner in all

He built a career on dark stages, scorched metal, and fragile narratives. Banks Violette looks back at the neo-goth label, the toll of self-destruction, and what it means to walk away from the art world and return on his own terms.Working between sculpture, installation, and sound, Violette treats subcultures, violence, and fandom as unstable stories rather than fixed identities. From Slayer panic and satanic scare headlines to burned stages and Jägermeister firepieces, his work tracks how trauma gets turned into image, how labor disappears behind polished objects, and how an artist survives a system that rewards collapse as much as rigor.He explains:* Why “neo goth” was a convenient label that flattened a generation of young artists and obscured the real story of illness, addiction, and burnout.* How murder cases, satanic panic, and The Sorrows of Young Werther reveal a long history of fiction being blamed for real-world violence.* What it means to make work about calamity and Weegee’s photographs without treating trauma as raw material or spectacle.* How class, fabrication, and hidden labor structure the work, from doing everything by hand in Brooklyn to orchestrating 14 chandeliers for Celine across the globe.* Why drugs once felt like the only rational way to survive a tiny career window, and what it took to trade that pace for a decade of near silence, family, and fishing.* How fan-level enthusiasm for Void, Smithson, and Judd can coexist with critical rigor, and why reentering the conversation matters if art is to function as a real dialogue.(0:00) Welcome and the Weight of First Impressions(3:00) The Blowtorch Narrative(7:00) Noise, Sunn O))), and the Gravity of Sound(12:00) Polke, Richter, Danto, Judd(19:10) When Stories Justify Violence(22:00) The Accomplice Problem: Art, Trauma, and Ouija(26:00) Invisible Labor, Class, and Who Really Makes the Work(34:00) Drugs as a Work Tool and the Decision to Disappear(47:00) A Decade Offstage and What It Means to Come BackFollow Banks:Web: https://ropac.net/artists/85-banks-violette/#Read: https://vonammon.bigcartel.com/product/banks-violette-no-title-gas-station-black-versionInstagram: @banks_violette_616Full TranscriptAjay Kurian: How are you feeling?Banks Violette: I feel like I’m catching up on sleep still at age 52. All the sleep that I missed in my twenties and thirties, I still feel like I’m trying to balance the books.Ajay Kurian: That’s fair. You know, there’s a camel theory of sleep that you can kind of keep it and grow it in a hump, and deposit it when you need it.Banks Violette: I have no idea what you’re talking about, but it sounds absolutely accurate.Ajay Kurian: This was the project that I really did foresee, and this was the moment that the press was largely calling a neo goth moment. There were a handful of artists at that time that were really maybe engaged in a neo-goth visual culture. But I wonder, did it feel like the right way to talk about your work at the time?Banks Violette: No. It felt like a convenient way of talking about the work because it was a way to organize a group of disparate artists and make them legible in a way that was easy for people to encounter. Ideas that were potentially easy to dismiss unless there was some kind of lens attached to it. Whether or not I ever felt like I shared a lot of commonalities with the artists that I was grouped with — not necessarily.Ajay Kurian: Of that sort of generation, were there artists that you felt like were your peers or fellow travelers?Banks Violette: It was always presented as if there was much more closeness, or similarity in our practices, when there wasn’t necessarily in actuality.So the person I can point to that I think I had the most in common with when I was working actively, was probably somebody like Gardar. He had a preoccupation with a specific period in art history, a specific kind of discursive lens that he was attaching to things, and a certain kind of political bent. I think that there were a lot of ways that we dovetailed, but then there’s a lot of ways that we were totally different.The one thing that I did have in common with a lot of the artists that I was grouped with was that we were all young and pretty engaged with self-destructive behavior. And you know, the artwork kind of reflected that. So on one hand, there was this goth thing, which is an inaccurate way of organizing that work, and then there’s what was actually taking place. Which was, here’s a bunch of people who were all probably not well, and let’s lump them together. But you can’t really be like, oh look at this group of artists who are all drug addicts. So instead, you know, there’s an easier way of doing that and say oh they’re all goth.Ajay Kurian: So they almost said that though.Banks Violette: Yeah, it was implied.Ajay Kurian: I want to go back to that era where you started in New York in order to understand where you are now. The image that I feel like was paraded around the most was probably this one where you’re lighting a cigarette with a blowtorch. When you search the name Banks Violette, this was the image that used to come up. Now I think Vanity Fair has the rights to the image and they’re not putting that on Google.Banks Violette: I had this experience, and I know a lot of other people, my friends and my peers, all had this kind of experience with people coming to the studio to take photographs of you working. And it would somehow turn into the “hey, do this, hey, do that”. And yes, I did definitely light my cigarettes with map gas, a hundred percent, hand on the Bible. I use propane to light cigarettes all the time, but that was definitely somebody trying to elicit that. So on one hand, that’s accurate. On the other hand, it is a totally theatrical presentation of what that moment in time looked like.If I had been necessarily in my right mind, would I have chosen to reveal that part of myself publicly? Probably not. I think there was a lot of that. People weren’t necessarily in the greatest position to author the way they were being perceived by people.Ajay Kurian: It was a fascinating thing to watch in the studio. Because on the one hand you were really private and there were things that I think were just for you and your world. And then on the other hand, seeing how you were able to move. For instance, I think the first time that I met you, I was an intern at the Guggenheim and they were doing this young collectors thing and came to the studio and you had this giant Jagermeister piece that you were working on. It was an incredible performance. It was all the ideas that you were thinking about, but it was the first time that I was hearing it. So you’re stringing together Smithson, Hegel, satanism and all these things that I am hearing for the first time. And I was like, this dude’s a fucking genius. Not to say that you’re not, but —Banks Violette: If I’m stringing together Hegel, satanism, and Smithson, then yeah, I’m definitely not.Ajay Kurian: What was fascinating to see after that was that you’d have other studio visits and this performance, it would be the same speech. And I was like, oh right, there’s some preparation to this. For a young artist, it dialed me in because it made me think about how none of that was untruthful and none of that was coming from a dishonest place. But you’re asked to do this thing again and again, and how do you not think about what this looks like, feels like, and appears as. How much of that was on your mind in that, like period of time?Banks Violette: The things that I refer to, gravitate to, and cite within my practice are things that I care deeply about. But they’re not necessarily things that somebody has deep and intimate knowledge of. Smithson’s practice or satanism or whatever it happens to be. These are the things that I think about a lot and I don’t wanna misrepresent them. Part of doing these things is figuring out a way to translate what is potentially this kind of esoteric language or something potentially marginal, and making it into something that other people can find themselves within.You know, the perfect example of that is a band called Sun, that I’ve worked with a number of times. Incredible musicians, incredible composers. But the last time I saw them — they just played at Lincoln Center last year. What they played at Lincoln Center was identical to what they were playing in Brooklyn in like 2000 at some lousy club. What they were doing in Lincoln Center is the same, but those things are really sophisticated. It is really easy to get caught up in the more outrageous aspect of what they’re doing or pointing a finger at something and being like, oh look how crazy this is. That’s never been something I’ve been interested in. I’m interested in these things. Deeply, sincerely, and I’m trying to communicate that. And there has to be a way of translating that. Sorry, this is all very vague.Ajay Kurian: I want to come back to sincerity ‘cause I think it holds a major role in how the work comes about and also the positioning of certain things. But maybe it’s also a good time to talk about where that deep sincerity for expressing yourself came from? What’s your background and your background with art? What made you gravitate towards art in the first place?Banks Violette: I’ve always made things. That’s kind of how I understand the world. I was always a kid in the back of the class, sitting and drawing and definitely not relating to anything outside. That’s always been how I view things or related to the world.I didn’t have any kind of background with contemporary art and certainly didn’t really know that much about art history. I had one of those sort of perfect, kind of what you hope for is the experience that people have in college. Which is not a vocational route, but you go there and you’re exposed to new information and your world expands and that’s how you discover what you want to do.So I went to undergraduate in New York City after

He builds with fabric, scaffolding, and light — Eric N. Mack on tenderness as structure and the unseen labor that makes art visible.Eric N. Mack works between painting, installation, and fashion, reimagining how material, care, and collaboration shape contemporary image-making. His large-scale assemblages drape and lean, collapsing distinctions between surface and structure, styling and architecture, autonomy and support. His practice reveals how beauty, fragility, and display coexist within shared spaces of labor and care.He explains:* How gestures of rupture, cutting, and collage become ways to think through care, not violence.* Why stylists, curators, and unseen collaborators form the hidden architectures of art.* How fabric behaves as both image and body — draped, suspended, and alive to air and time.* What scaffolding, transparency, and light teach about the precarity of presence.* How tenderness and structure coexist as the real politics of display.* Why every act of making is also an act of attention — a choreography of support between maker, viewer, and space.(0:00) Welcome + Intro(01:00) Rupture, Reflection, and the Studio as World(05:00) Grace Jones and the Clarified Aesthetic(10:00) The Unseen Hand and the Architect of the Image(15:00) Collaboration, Care, and the Space of Display(20:00) Fabric, Fragrance, and the Politics of Form(30:00) Craft, Styling, and the Education of Looking(33:00) Art School, Value, and the Work of Belief(40:00) Draping Architecture and Breathing Structures(47:00) Fragility, Care, and the Social Life of ObjectsFollow Eric:Web: https://www.artsandletters.org/exhibitions?slug=eric-n-mackInstagram: @ericnmackFull TranscriptAjay Kurian: When you’re putting together a show, I know you’ve talked about art being present for the world’s brutalities, but how do you conjugate that or stay present in the work with that? It’s not even saying that you have to, because it’s not your responsibility to do so. It’s more so, I see glimmers and I see the way that you think about how things come together and how they kind of fall apart.Eric N. Mack: Yeah. I have a lot of epiphanies that sit in the studio, that come from the studio that end up allowing me to think about the external world from the happenstances in the studio, and from coordinated or measured gestures of rupture. And those ruptures could have implications of or sit alongside what folks could regard as kind of a material violence, or violence to a material, or decomposition, or collage, or something for the work to feel chopped like the ingredients are chopped up.I love a good metaphor, like a good salad, it’s aromatic with all the ingredients. Nothing overpowers one another, but it’s transformative. It holds meaning, sustenance, and maybe a level of a counterpoint, maybe the sunflower seed gets stuck in your teeth or something like that, you know?Ajay Kurian: You gave us a lot to chew on, even in the press release. At the end of that, there’s literally seven hyperlinks to run through. We had The Clark Sisters, Nina Simone, a trailer for the Unzipped documentary about Isaac Mizrahi, the Harlem Restaurant of which the show was named after, Sinners movie tickets.Eric N. Mack: Why not?Ajay Kurian: And Grace Jones on an Italian talk show or an Italian show.Eric N. Mack: A talk show, I think. It could have been Eurovision.Ajay Kurian: But that was serious. She was really in her pocket.Eric N. Mack: Yeah, it’s intense, ‘cause she’s in drag in a way. You know, she’s wearing this wig and I was like, the wig is architecture and the wig is like a hat. She’s architecture. If you’re watching the YouTube video or seeing the performance at the end, this camera pans out and she leans back and someone catches her as she falls and snatches her wig. Then she becomes this doll, this kind of copy of herself, this quotidian, you know the things that she would process with Jean Paul. She’s always around and I always think about her. She’s an interesting marker, because she’s such a clarified aesthetic. She’s a sound, she’s a voice and she also possesses her own tension. There’s incredible softness and vulnerability, but she’s also a tank, you know? The thing is, these images are also ones that she’s used herself. I just think that she will always be relevant.Ajay Kurian: There’s an ownership over the image too. There’s a way in which she’s self representing and it feels beautiful and antagonistic, but also really generous. To be both aggressive and generous at the same time isn’t an easy thing to do.Ajay Kurian: But I feel like, for her embodiment to be a black woman who is beautifully angular and masculine and feminine at the same time, it’s a lot to have to deal with, specifically in that moment of pop culture too.Eric N. Mack: Yeah. She’s an artwork. She’s her own artwork. There was an exhibition I did in London and I kind of couldn’t stop thinking about Misa Hylton. I couldn’t stop thinking about her. She was a stylist for Lil’ Kim and Mary J. Blige. So she was a part of this kind of bad boy regime, but she was a part of their visual representation. She’s an iconic stylist. Everybody takes notes from her in New York.Ajay Kurian: Really? It’s so interesting ‘cause I think you’re the first artist that I’ve talked to that holds stylists in this regard. That the grooming of an image, the understanding of what it takes to put together a scene, an idea, a world building essentially, that it’s happening completely behind the scenes. You’re really picking out these people to be like, you’ve changed this whole scene.Eric N. Mack: I mean, it’s what we do as artists. It’s just asking questions like, okay, what’s in the byline? Who did this? Who’s the architect? She called herself the architect, and I respect that. There was an awareness and a renewed understanding of her importance as these looks became more prominent again.The nineties in general as a kind of nostalgic, bygone era, that we were there for. So it also is an interesting thing to think about, who made the thing that sits in your heart or that sits with you, that rests in your references, and that you connect with? Who made that? Obviously, I mean, that’s what we do. That’s research.Maybe people don’t look at the production of the image as much as, you know, there’s a lot of romanticism around the fashion designer and who made the garment, but you won’t see the garment without seeing how it was put together and how it was aligned. The tension.Thinking about my good friend, Haley Wollens who has been working for a long time. I think more recently she’s done Dsquared, she’s done Au Claire, she’s done all of these important brands that end up being reconstituted, recomposed by this unseen hand.Ajay Kurian: That’s the thing. It’s a level of research that is fascinating to me because I think everybody gets caught up in the director and the designer. Even when you’re a kid, you watch the movie and you like the movie.Then there’s the kid that finds out who the director is. Then there’s the kid who finds out who the producer is. That’s a different kid.Eric N. Mack: It is a different kid. But you know, sometimes it’s meant to be that way. It may be structured for folks to be completely enamored with the superstar, with the actress or the actor. It was designed that way, you know?Ajay Kurian: Now I want to see behind that.Eric N. Mack: That’s what I do. I mean, that’s what I’m interested in. Questioning wasn’t enough, and was never enough. Like thinking about Amanda Harlech, she’s an incredible stylist who was a big part of the way that we experienced the early days of John Galliano and some of the more important days of Karl Lagerfeld. I mean, she’s established, but she’s a visionary and at a certain point she kind of sought Galliano out when he was finishing his degree at CSM. So there was a premise that was going around between them. They were collaborators. There’s something about the unseen magic in between these figures and some of the social qualities of discourse between two people that end up generating meaning for so many.Ajay Kurian: So what’s the plural for you? Do you feel like there’s similar relationships that you have in your practice? Of course, I know that you actually work with stylists and designers. There’s plenty of collaborative things that you’ve done. But when I think about the kind of classic idea of a painter, for instance. You have a studio practice, you go to the studio, you work, you come home and that’s potentially a very solitary thing.Eric N. Mack: I mean, it’s up to me, and it’s up to artists to be able to question that, to reposition that. Sometimes that works, and the main collaborator at this point is the curator.Eric N. Mack: So for this exhibition, shout out to everybody at Arts and Letters, Jenny Chasky, Nick and Juan — these are really important people in actualizing the exhibition. It was through conversation and also acknowledging that everybody, they got eyes and it matters like that we are all seeing. And I’m not afraid to ask what people are seeing right in the room. Sometimes people think that just means I don’t have vision myself and that’s stupid. But I think also with time, it’s also a practice for me, to see what I get from that.Ultimately, I’ll make my own decisions about these things. But it’s really important for me to be able to reflect from people who are familiar with the space that I’m working in currently. You know, I’m scratching my head, I’ve been here all day, why is this not working? There’s people who have been up on the lift and been able to see what the space looks like from all these different vantage points. The material that the walls are made from are all significant aspects of architecture that many of us can take for granted.Ajay Kurian: I’ve been lingering on this picture, because it’s kind of the first thing that you encounter when you walk into the space. There is a piece suspended from, and kind of draping, in the wind. And it was

He builds worlds from devotion, labor, and light. Raúl de Nieves on myth, death, and the joy of transformation.Raúl de Nieves is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice spans sculpture, performance, stained glass, and music. His work merges ancestral craft with queer exuberance, creating ecstatic spaces where life, death, and rebirth coexist. Known for his intricate beaded sculptures and radiant installations, de Nieves transforms discarded materials into devotional objects that question permanence, value, and faith.He reflects on:* Why failure and fear are essential teachers* How myth, labor, and ritual shape his understanding of transformation* The link between spirituality and psychedelia in his creative process* The politics of beauty, excess, and craft* How performance and collaboration sustain his practice* The tension between art and commerce—and what it means to say yes* Why joy, respect, and self-love remain his most radical tools(0:00) Welcome + Intro (1:00) The Origin of “St. George and the Dragon”(10:00) Death, Culture, and Safety(21:00) Excess, Labor, and the Ephemeral (31:00) The Whitney Window (35:00) The Carousel and the Brand (43:00) Pact with the Devil (47:00) Celebration and Decay (53:00) Belief and Legacy (56:00) Joy, Respect, and The Smashing PumpkinsFollow Raúl: Web: https://companygallery.us/artists/raul-de-nievesInstagram: @noraulsFull TranscriptAjay Kurian: Hi everybody, thank you all for being here. Welcome to our NewCrits Talk with Raúl de Nieves! I’m gonna give you some background as to what NewCrits is, I’m gonna give you a little introduction to Raúl, and then we’re gonna get into the conversation.NewCrits is a global platform rooted in aesthetic education. We’re committed to fostering critical care, rigorous inquiry, and artist-to-artist dialogue. We offer mentorship and courses that challenge the assumptions of traditional art institutions while honoring the intensity of their best methods. We have crits, but we don’t think about crits as a way to tear you down to build you up. That’s trauma we don’t need anymore. Our offerings are designed for artists at any stage, especially those seeking meaningful critique, rooted in trust, discernment, and deep attention. These talks are an instantiation of that.The way that I think about art will be on display. This kind of conversation is the kind of conversations that we have in crits. It’s one where we’re building together.Now let’s get to the main event, which is Raúl here.Raúl de Nieves: Hello everyone.Ajay Kurian: All right, we’re gonna start with this image. I’ve known Raúl for some time now, but we really got to know each other better during the 2017 Whitney Biennial, which we were both in. We were both also part of the five artists that were asked to collaborate with Tiffany and Company.So we were spending a lot of time together and it was really nice. Raúl is one of those artists where you can’t tell if the art is an extension of him, or he’s an extension of the art. There’s a purity and transparency to who he is as a person and an artist, that feels free of shame and free of hiding.You’ll see the dark and the light. He’s joy and sparkle at times, but he can access a banshee scream and speak from unknown deaths as he does in his band Hairbone. Dark and light, life and death, are not seen as mere opposites in his work. They are a faded coupling, archetypes, and fantasma characters emerge throughout his sculptures as if enacting scenes from forgotten religious books, rituals, and beat through much of the work in ways that give them new life. There’s plenty of art that looks to religions, but few works of art inject a new spirit into that old fist to open it up.Raúl has a new exhibition at Pioneer Works that just recently opened. The space is wide and gleaming with colors pouring through the windows. He’s created new stained glass works for the windows of the entire building. They’re modestly made with tape and colored plastic, but the effect is regal. The colors almost tune a frequency that makes you smile. So when you see texts that might be darker, more bodily, even a little gross, you accept this as part of the light too. Nothing’s left out. Everything feels redeemed.After spending so much time seeing how Raúl creates, thinks and cares, I was and am convinced that this person is a star. Not a star in the sense of celebrity, although there is that, but in the sense that he radiates with an unflinching and holistic energy as if he simply is a star. I think it’s easy for us to see someone like Raúl whose light shines brightly and think that’s just who he is, that it’s not the result of enormous amounts of work and discipline of the ability to bring death to an old self in order to birth a new one and find joy again and again.A person like that right now is worth talking to and hearing their stories. So please help me welcome Raúl.Raúl de Nieves: Thank you. That was very nice.Ajay Kurian: How are you feeling?Raúl de Nieves: I feel great. Today was a lovely day and being here is so nice. To be able to talk to you and share a moment of my life and just some of the things that mattered to me. So thank you for having me.Ajay Kurian: It’s really a pleasure. It’s an honor. I have loved your work, I’ve loved seeing it and I love learning more about it. This image was one that came up when I was reading about the work. I’ve seen this story told many times in your work, but this is from 2003 to 2005. This is a story of St. George and the Dragon, and I wanted to start here ‘cause I think there’s a lot of things that are formative in this particular image, the story itself and how you saw that story.Raúl de Nieves: I moved to San Francisco in 2002 to attend the CCA college. And unfortunately, I wasn’t able to take into the school because of the financial situation that I was in. So it’s really nice to know that you are providing mentorship to students, because there wasn’t anything like that in 2002. The internet was just starting and moving to San Francisco was such a dream of mine and I made it happen even though I didn’t end up going to the school. For me, the bridge of San Francisco, which always shined so much to a forgotten soul or this idea of the hippie, the queers, gay culture. It really attracted me to this idea of knowledge. But once I couldn’t attend the school, I had to find my own mentorships, and I saw that through my friends.The image of St. George and the dragon appeared to me through a woman who was selling embroidery at the store that I was working at. I ended up buying the embroidery off her and I started to really think about how I grew up in a religious household that spoke about angels and the defeat of the self. But in a more Catholic way, where you have to repent your sins and think about what it means to not follow the status quo of a normal way of thinking because heaven is the ultimate power of our existence. St. George, to me, became this mantra. I started to really ask myself who I was in the picture, and I decided to think that I was all aspects of this fable.The fable talks about a dragon that houses itself next to a water well, and the town is in fear that this dragon is gonna drink all their water. So they must gather their beans into a sacrifice because the dragon ate all the animals. As if the dragon shouldn’t eat the animals because the humans are eating the animals. I don’t think that the saint really exists in the image because that is up to the future to decide.So in a sense, I thought about some of the people in my life that I felt had that idea of themselves. Not going to school gave me an opportunity to seek these kinds of icons or lessons through things that appeared to me and I frantically started painting this painting over and over and over again. My goal was to paint 50 of them. I still haven’t painted 50, but once I moved to New York, it’s almost like the image faded away somehow. But it’s something I constantly go back to, and when I recognize it through my journeys, it reminds me of finding things to reflect on.Ajay Kurian: The part where you say that you can be every single character in the fable is what stands out to me because there’s the dragon or the snake, there’s St. George, and then there’s the townspeople that are afraid. There’s this sense that St. George is banishing the dragon, and there’s a sense that people think it’s a dragon but really it’s just this snake and it’s not that big of a deal. They’re afraid of this thing that maybe they shouldn’t be afraid of. To be able to embody the people that are violent and fearful, to embody the saint who comes to save the day, and then to embody this dragon figure is a lot to think about, especially right now.I wonder, can you still embody all those positions or do you feel like you have a different kind of sense of self right now?Raúl de Nieves: I definitely can. I think fear is man’s best friend as they say, and sometimes we really have to get to know our fears in order to understand what they look like.It’s one of the hardest things that we can allow ourselves to communicate with. Because sometimes that comes with a tragic death, addiction, or just being alive. I thought about this and the fact that this dragon was portrayed as the entity of the end of life. A dragon is essentially a mythical creature, so this idea of the myth or the flamboyant also became what I was thinking about. I was like, oh there is a fear of the other side of the human being that maybe we aren’t allowed to or we shouldn’t exercise. Which is our inner divas, our inner goddess, or our inner demons. But I still relate to each character because not every day is so jolly. One of the things that I’ve been trying to continue to exercise within myself is how to let go and what does that mean? When letting go, is it an idea or is it part of the past?Ajay Kurian: When was the first time that you felt like you befriended your fears?Raúl de Nieves: Definitely being in San

She builds archives, conjures futures, and questions everything. Tamika Abaka-Wood on ritual, refusal, and the joy of cultural strategy.Tamika Abaka-Wood is a cultural anthropologist, conceptual strategist, and artist whose practice moves between community building, archival work, and spiritual inquiry. She's the creator of Dial-An-Ancestor, an ongoing project that collects voice notes as offerings to the past, present, and future. Her work resists categorization, merging care and critique, and often asks: what are we remembering, and who are we remembering for?She explains:* Why she’s more interested in frameworks than mediums* How Dial-An-Ancestor creates a space for grief, communion, and speculative healing* The tension between facilitation and authorship in creative work* What it means to build archives that feel alive—not extractive* How refusal and withholding can be generative tools* Why she resists the singular identity of “artist,” and what she embraces instead* The ethics of visibility, looking, and representation in public programming* How joy and mischief shape her strategies for imagining otherwise(0:00) Welcome + Intro(08:30) Refusing the artist title, reshaping the role(13:00) Strategy as creation(17:22) Dial-An-Ancestor: calling in future histories(26:08) Branding is not world-building(30:31) Building intimacy into the infrastructure(35:03) Refusal is not a pause, it’s a position(44:00) Grief, play, and spiritual maintenance(48:21) How to get involved with NewCritsFollow Tamika: Web: https://tamikaabakawood.com/ Instagram: @tamikaka Learn more about Dial-An-Ancestor: https://dial-an-ancestor.com/Full TranscriptAjay Kurian: Hi everybody. Welcome to the July NewCrits Talk and Summer Party. Thank you all for coming!I met Tamika through my partner Jasmine, who's here tonight. From day one she was electric, a mile a minute, excited about anyone's excitement, game for anyone's game, a facilitator par excellence. Whatever you supplied, she'd give back threefold with tangents, detours, serious things and fun things, codified and color coded. Tamika wants to help. She wants people to see their ideas through, and to excite them to build the worlds they're making and to believe in the possibility of a different tomorrow without blinders on. She's not deaf to misery or darkness, but somehow she manages to channel her best energies to maintain a joyful persistence.It's only recently that Tamika has felt comfortable calling herself an artist, and she probably wants to chime in right now and question the importance of the name. Anyways, she has self-identified as a cultural anthropologist and I think that's definitely true. Her ongoing project, Dial-An-Ancestor, is a beautiful testament to this where she gathers future histories into a building archive.But her work as a kind of conceptual strategist is also its own form of cultural anthropology. And I'm interested in people who are creating in multiple ways in multiple worlds. But really I insist on the term artist, not because everyone needs to be an artist, but because I think it allows her to momentarily assume the role of head creative and not facilitator.She's not alone, of course, but sometimes when you're in an ensemble, it's time for your solo. The group steps back and lets you play because what you have is special and singular, and the group knows you'll come back. But for that moment, it's about you, and this is a chance for that to happen. This is Tamika's world, and tonight we're all in it together.Please help me welcome Tamika Abaka-Wood.Tamika Abaka-Wood: That was so special, thank you. I feel so shy, I really do. That was beautiful.Ajay Kurian: Of course.Tamika Abaka-Wood: Thanks for having me here. It is still surreal.Ajay Kurian: What's surreal about it?Tamika Abaka-Wood: What is surreal about it? I think you touched on it there. I definitely feel more comfortable in a facilitator role — a question asker role. You anticipated my reaction to the word artist, and you're a fine artist. Big A.Ajay Kurian: So they say.Tamika Abaka-Wood: Who's they?Ajay Kurian: I dunno.Ajay Kurian: There are prompts over there, so I'm gonna ask you one of the prompts and then we'll get into what these prompts are. How's your head, your heart, and your body right now?Tamika Abaka-Wood: Okay, let's start with body. I came back from London yesterday last night, so in my body it's like midnight, which is way past my bedtime. But my body feels relatively relaxed. I feel like my heart's beating maybe a little bit fast and I'll ease into this weird space.My head feels really unburdened and my heart's really open. I went to London because my mom is sick and I got to be there with her, and it reminded me that life is so much more important than anything else. And doing it with people is so much more important than anything else. So I feel really grateful that I was there and I feel really grateful that I'm here.Ajay Kurian: Oh, I'm wishing your mother well.Tamika Abaka-Wood: Thank you. How's your head, heart, and body?Ajay Kurian: Let's see. I'm only gonna answer so many questions from you but I'll answer that one. My head is clear. I just got back from Bard where I was teaching for the last three weeks, so I need to clear out a little bit more. But I feel like, as I prep for these things, I try to do some breathing and get that clear.My heart is always open in these conversations because really it is a very responsive thing. I'm here to celebrate the things that you do and that makes it easy to have an open heart. And my body's okay.I want to start with Dial-An-Ancestor 'cause I think it's probably the project that has created the most iterations. Maybe it's the thing that's built a momentum in which this becomes an artistic practice and one that's of course related and implicated in cultural anthropology.But this is a very specific project and it's one that's very open and you have the ways that you want it to be. And that's interesting to me 'cause this is this is a vision — what you want it to be. So I want to hear the beginning. I want to hear how this started and kind of the bones to the flesh to where we are.Tamika Abaka-Wood: So Dial-An-Ancestor is a techno-spiritual hotline. It is gonna exist for a hundred years, which is obviously beyond my lifetime, purposefully. It asks people to do two things; to consider who is asked to listen and who is asked to speak. That is the most blunt, simple two questions that this artistic process asks. But it came around in 2021 when I was pregnant for the first time. I know it's so biographical, but I just think I wanna go straight there with you. I was pregnant for the first time and it was unexpected and it was really exciting and scary, and made me realize how precious and precarious time is.At the same time that I had this germination of life within me, I also got a call from back home in London that my dad was really sick, so I've got two parents that are sick at the moment. So it was conceptually holding life and death at the same time and being like, oh my God, I'm the link between what was before and what is to come, what do I wanna do with that?So it made me think about ancestry and links between the past and the future, but within my body for the first time. That's where it came from within my body, but also it was 2021 and I was new in America.Ajay Kurian: That's lot of new things.Tamika Abaka-Wood: It was a lot of new things at one time. But it came out of a learning experience, so twice a week I got on Zoom with seven people who are strangers that I did not know, and we had a self-directed course that was about unraveling our relationships to time. I know, it is like the weirdest thing to do.Ajay Kurian: How did that even happen?Tamika Abaka-Wood: I just know a guy that knows a guy. Honestly, that's how anything in my life happens. I have no idea. Just like through WhatsApp, there was this group.Ajay Kurian: Know a guy that knows a guy, that's like intellectual gangsterism.Tamika Abaka-Wood: No, true. Like I don't know anything. I just know people that know things and I get put on. So we were unraveling on our relationships to time, and this is where Dial-An-Ancestor really came from conceptually.Ajay Kurian: Of course it happened in a group.Tamika Abaka-Wood: It had to, there's no other way. Every good idea, if you really boil it down, comes from multiple dialogues and multiple references. Like you can't really locate it in one place or one person. There's a multitude of unraveling of references over a lifetime that leads you to one idea. An idea finds a person or a set of people at the right time.Ajay Kurian: And so this was that time. There were so many thoughts that were going through my head right then where I think that's true for all artistic creation. The funny thing is that when people take on the name artist, they do slough off the group. They’ll say that they're for the group. They’ll say that they're for the community. But there are instances, and I'm not damning all artists and I'm not saying that everybody does this — it’s not that severe. But there are instances where that dynamic falls away, and then the singular artist is raised up and we get the genius.And what I hear in what you're saying is that you're keeping all the things that make that rich and real and true. That's the time when I understand why maybe you shy away from the term artist because it does consolidate so much of that feeling of the one.Tamika Abaka-Wood: Ugh, yeah. So much of that is western ideology. It's never been real. It's never ever been a real thing. And this isn't to shun the idea of a singular artist, I think that's so important as well.Ajay Kurian: Absolutely.Tamika Abaka-Wood: I'm interested in the idea of the me within the we and vice versa. But for me, the way that I've been ignited, I definitely need external catalysts and factors to stimulate thinking and doing and practicing.I guess this is a really bastardized, quie