Contorted Worlds, Distorted Identities, and Cartoons as a Conduit: NewCrits Talk with Janiva Ellis

Description

She paints distortion, vulnerability, and the psychic residue of history — Janiva Ellis on contortion as language and survival.

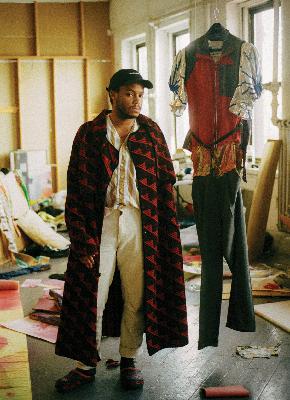

Janiva Ellis is a painter whose work stretches emotional and political registers through fluid mark-making, surreal juxtapositions, and animated dissonance. Her paintings contort and erupt, channeling humor, grief, and ancestral hauntings. She’s exhibited widely, including in the Whitney Biennial and at the Carpenter Center, and is known for refusing easy resolution.

She explains:

* Why cartoon logic and slapstick pain offer the perfect language for distortion, survival, and historical violence.

* How she embraces ambivalence by showing unfinished or uncertain work as a form of radical transparency.

* Painting not to perform virtuosity but to let discomfort, exhaustion, and doubt remain visible.

* Letting go of the “entertainer” impulse and choosing instead to rest, reflect, and resist institutional pressure.

* How working through rage, shadow, and cultural projection allows the paintings to become psychological landscapes.

Why she paints for the terrain she’s in and how Germany, Berlin, and Kollwitz shaped one of her darkest pieces.

(0:00 ) NewCrits Podcast Intro(1:34 ) Ajay Kurian introduces Janiva Ellis (08:02 ) The Cartoon’s Burden (17:00 ) From the Cruise Ship to the Studio (24:30 ) When Whiteness Becomes the Subject (32:00 ) Disillusionment and the ICA Show (41:00 ) Exuberance, Masochism, and Recognition (47:37 ) Working in the Dark: Technique and Intuition (54:10 ) Letting Go of Control and Embracing Vulnerability (1:00:44 ) White Spirals and Cultural Projections (1:07:18 ) The Value of Communal Witnessing (1:13:52 ) The Challenge of Raw Rage (1:26:59 ) Dream Recall and the Fade of Intuition (1:31:28 ) New Crits Upcoming Classes and Services

Follow Janiva:Web: https://47canal.us/artists/janiva-ellisInstagram: @janivaellis

—

Full Transcript

Ajay Kurian: Welcome to the 20th New Crits Talk. My name is Ajay Kurian and tonight for our 20th talk, we have Janiva Ellis here with us.

Janiva Ellis: Hey guys. Thank you so much for coming. There's so many people that I admire here and strangers who came because they care. So thank you so much.

Ajay Kurian: I'm gonna start with a little intro for Janiva and then we're gonna get into it.

Sometimes when a person contorts themselves for so long, their reality itself becomes a distortion. If a person forgets their contortion, then the distortion is reality. More often than not though, somewhere deep down, the score is being kept - and that's what keeps it a distortion. The figures in Janiva Ellis's paintings are living in this wonky place, where contortion and distortion meet, where internal and social realities commingle and conflict.

I think maybe that's why she favors cartoons. Because they can stretch like an accordion, get blown up by land mines, and freeze or burn without ever skipping a beat. They are projections of contortion and distortion. The cartoon, despite its flatness, here acts as an echo chamber for history's emotional and violent contradictions. Meanwhile, a richly detailed illusionistic landscape may in fact be entirely flat - a visual lie that we've accepted as reality. In the interplay, Ellis is able to conjure vivid but slippery tableaus that weigh as much on the sociopolitical as they do the privacy of one's most intimate thoughts.

She is a skillful conductor. The haze is intentional; the confusion is part of the pleasure, and the finish is meant to be a question. She's an artist who knows how to simultaneously set a trap and set you free. Please join me in welcoming Janiva.

Janiva Ellis: You tore that, you ate that the fuck up. Thank you.

Ajay Kurian: It's my pleasure.

Janiva Ellis: Thank you for seeing the work. Thank you for confidently putting words to it, engaging with it, and not shying away from your assumptions about the work because they're really right on and it’s cathartic to hear.

Ajay Kurian: Thank you, I’m honored. It’s not easy to write or talk about your work. I don't know the dynamic of how I'm supposed to play it all out because it's charged, and I think in this conversation it'll be really nice to talk about how those dynamics stay charged and how they move and change throughout the work. There's been a lot of changes and that’s the reason why I wanna start with such an early piece. We're gonna start here and then we're gonna go all over.

The development is amazing. I don't say that often and I'm not blowing steam. It's rare to see an artist where every show it gets better and better. I'm genuinely astonished because when I saw your first show, it was great but I'm curious what comes next. I remember Tyler the Creator talking about Vince Staples’ album. It came out and he was like, this is it. But then the next album was the one he was excited about.

Janiva Ellis: Totally. Oftentimes in the studio, I've processed the idea, but I still have to make the show. I'm halfway through the painting and I got the idea, but then I have to finish the painting and I have to finish the show. But I cannot wait to take what I've metabolized and bring it to the next project. I'm on the hook for this project and I do need to finish this and get it out, but there's already so much enthusiasm for what I wanna say next. Then in the next project, I don't know what I'm doing. While I'm making, I know what future me needs to do until future me is present me, and then I'm confused again.

Ajay Kurian: How do you stay in it and how do you keep that same energy?

Janiva Ellis: I don't keep that same energy. I think it's an underlying drive. Sometimes I try and let the energy of the past project evacuate by taking a lot of space or creating interventions in the work that are challenges so that the part of my mind that's stimulated by problem solving is activated again.

I try and take what I've learned and I'll keep notes. Sometimes I don't even know what that note meant, but let me interpret it in the now and run with that thread. So it's not necessarily about holding tight onto the thoughts that happened in the past, but maintaining the same enthusiasm around my curiosities and my desire to feel challenged by what I can create.

Ajay Kurian: This painting is called the The Okiest Doke from 2017.

Janiva Ellis: One of my friends said “don't get caught up in the Okeydoke”. It's either DeSe Escobar or Juliana Huxtable, and it could have just been the community. It could have just been something we all said.

But it was very much a 2014 “we're out here” vibe. As with a lot of my titles, they come from notes I had taken about things I had said, or friends of mine had said on nights out about the predicament we'd find ourselves in and the joy we'd find in feeling like we were able to put language to this spiral we were navigating.

Ajay Kurian: It always feels that way. The titles catch a vibe. I understand it sometimes and other times it washes over you. But then you click with the vibe of the image, and you can feel that vertigo of where the picture takes you to.

Part of why I wanted to start here is this cartoon hand. This communion into cartoons is an interesting place to start, and also how you continue to use the cartoon in the work. In my understanding, the history of cartoons is a pretty fraught one, especially as we get into Looney Tunes and all that. The precursors of those cartoons is essentially seeing blackface and minstrelsy turn into the cartoons that become beloved characters and then become these characters that never die. They can always be distorted, can always work harder, can always explode, freeze, do whatever, and just come to life again. For that to be the person who's giving the wafer here feels wild.

Janiva Ellis: This the cartoon’s burden. It’s like the burden of constantly having to endlessly embody a projection. When I started doing cartoons, it was literally out of the need for speed. I was taking my practice really seriously for the first time, and I felt a lot of shyness around pursuing what I wanted to pursue.

I really wanted a level of grandiosity that I didn't know how to achieve and I also had a lot of self-doubt. So I decided, let's just go back to basics. You can communicate the things you want very quickly and easily by cartooning, and you can re-access your hand and your ability to draw by using cartoons.

I think the fact that it speaks to the fraught of the way that white violence depicts blackness and the way that whiteness cartoonized black people was not the starting point. There's just so many moments where it was like, I'm gonna do this. Then the funny byproduct of that is that there's a critique to be had about whiteness. It's not the point, but oftentimes it's just there.

There's a painting I did of a woman and I made her into Pinhead. Then I did some research on Clive Barker, who made Hellraiser. But where did Pinhead come from? And it came from African sculpture and I wasn't trying to give that, but obviously it gave that, and as I was painting, it worked out that way.

There's violence woven through so much pop culture and so much of things I'm referencing from an organic place, from a place of resonance, that it doesn't take too much to connect those dots and I can just riff without trying to make a heady dialogue around blackface. It's already there. The history is there. Early on, people were asking me a lot about blackface and I'm