Discover A Dash of Coldwater Economics

A Dash of Coldwater Economics

A Dash of Coldwater Economics

Author: Michael Taylor

Subscribed: 0Played: 1Subscribe

Share

© Michael Taylor

Description

Scan Widely, Watch Closely. For years I've tracked around 500 data-sets from the world's leading economies every month to produce the most data-rich suite of shocks & surprises indexes. When something catches my eye, this daily podcasts talks about it . . . briefly.

148 Episodes

Reverse

In which I look at the rather improbable improvements in Japanese capital investment spending, and Germany's construction spending. Both would seem to run counter to the rather dark background of trends in return on capital, and profits. Nevertheless, maybe something surprisingly counter-cyclical is happening.

In which, as usual, I stand under the cataract of global economic information and try to catch whatever fish I can.

This episode I also look at the 2019 outcome for China, and argue that it was a year spent treading water - neither waving nor drowning. There were some mildly encouraging signs, but the real story, I think, is that those mild upward inflections were bought at the cost of neglecting long-standing problems, or even abandoning earlier attempts to fix them.

There's no reason to expect 2020's outcome to be much different.

Quite a start to the New Year: World War III declared and then seemingly forgotten; global data mildly positive, and the six-week signal in positive territory (glory be). A good week for Asia and Europe, but a third disappointing week for the US. Quite possibly it really is time now to get on recession-watch for early-mid 2021.

And finally, I have some questions about what it means when 'capital raising markets' become 'capital redeeming markets', as they did in both the US and Eurozone in 2019.

Any comments, reactions and queries happily received at mtaylor@coldwatereconomics.com

Until next week . . .

Thanks

The holidays bring a much reduced data-flow from US and Europe, whilst Asia continues to report much as usual. So this episode tracks developments showing up in that data for the two weeks. In particular,

I look at the way inventory-clearing is improving US trade data at the cost of depressing industrial activity;

I look at the strange broad improvement in South Korea's recent data, and question how it can be justified;

I look at the dramatic erosion of Hong Kong's fiscal position, which unless Beijing gives them a pass, will have to be dealt with;

And I look highlight the two or three piece of data to come from Europe over the holiday period which just might be significant.

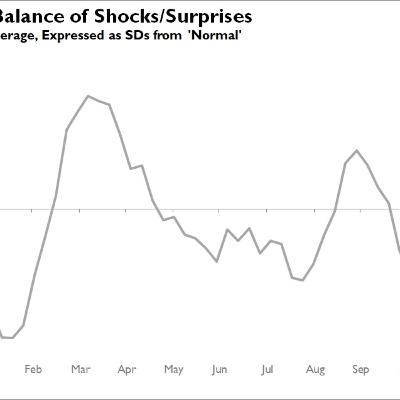

This is the Shocks & Surprises Global Weekly Summary for week ending 8th May.

It takes issue with the idea that 'scar tissue' from the current lockdown will inevitably mean we can expect only a lacklustre recovery.

An audio version of my Shocks & Surprises Global Weekly Summary for the week ending 1st May.

It's a trial endeavour - I hope it's useful.

Christmas week brings a lull in the data-gusher which I try to understand and control each week. So this week I look at what I think have been the characteristics of 2019. Without wanting to embrace Scrooge-like gloom, I have to say that 2019 was marked by Funk, Lies and Displacement Activity. Let's at least grasp that and hope that 2020 will bring something a little better, a little more honest, and a little more imaginative from policymakers.

Each month I look at approximately 500 different datapoints from the world's leading economies, and identify those which land a standard deviation above or below where they 'should' have been, according to consensus or trend. This allows me to track the health of the world economy in near-real time, as well as identifying those directions which might be telling us something about the longer-term picture.

This podcast summarises the results from the previous week.

The US July CPI result was better than expected, with headline inflation moderating to 8.5% yoy (from 9.1% in June), mainly thanks to a 4.6% mom fall in energy costs. This was on the back of a 10.4% mom fall in Brent oil prices and a 8.5% mom fall in Nymex natural gas prices. It is not obvious this is being repeated in August: so far, on average oil prices have fallen a further 7.5% mom, but gas prices have rebounded 12.6% mom, and overall the CRB index, which fell 9.5% in July, is almost unchanged.

Still, July's result is strong enough to allow us to scale back the likely inflationary trajectory in the US, with it now expected to peak at 9.1% in September, before drifting down to below 8% by end-2Q23.

But two caveats. First, I'm fashioning these trajectories from the 6m deviation in 5yr seasonalized trends - but volatilities in CPI indexes during the last six months have been consistently dramatic (both above and below trend), and in some cases (UK) positively freakish. So even a 6m trend assumption isn't looking particularly stable month-on-month.

Second, whilst inflationary pressures may be moderating in the US, they are only now beginning to show up in force in NE Asia. Overall, this means that my measure of global aggregate inflation continued to rise in July. . . .

I'm less concerned with the recession/no-recession arguments (hey, don't US politics just absolutely fascinate you? Me neither), than with the implications for profits and stockmarket valuations. Three observations:

1. Regardless of headline GDP, once you strip out extremely volatile inventory-flows, there's been essentially no growth in final sales of domestic product now for five quarter. There's just no momentum at all.

2. The massive fiscal stimulus has not yet completely been washed out of the Kalecki profits reckoning. I calculate profits were down 7.4% qoq and 19.4% yoy, mainly thanks to the fiscal deficit moderating. But there's worse - the profits/GDP ratio has fallen to its lowest level since 1Q16 - so there's cyclical as well as one-off structural pressure at work.

3. All of which means the S&P500 remains overvalued on my slow-model basis, which has been essentially on the money for the last 30 years. July's rally will extend that overvaluation. So the vulnerability continues, and rises.

The speed and severity with which data from the US has collapsed over the last month is extremely unusual. Why is the outbreak of inflation doing such damage so quickly.

One reason is the way in which the US profits model has changed over the years, until since 2000 to the present day, 77.6% of Kalecki profits are attributable to household and government dissavings, whilst only 22.4% come from net investment and net exports. Compare that to 1960-1980, when net investment and exports accounted for 65.7% of profits, with h'hold and govt dissavings generating only 34.3%.

Let's state the obvious: if your profit model depends disproportionately on h'holds and governments spending more than the earn, sooner or later, even the strongest financial balance sheet will become impaired, fragile. And it's that financial fragility which is kicking in, and kicking down, right now.

Two things today: first, a closer look at the ECB's so-called 'Transmission Protection Instrument'. Short take: it's open ended, with only decorative conditionality. The real constraint is that it mustn't inflate the ECB's balance sheet. So if it wants to do anything other than short-term fire-fighting in (say) Italy's bond market, it will have to do so by selling (say) German bonds. That'll make ECB meetings fun to watch.

Second thing: today's UK public sector deficit of £22.1bn featured an astonishing £19.9bn in interest payments. That's 23% of total spending, which is 6.2SDs above the long-term average. Cui bono? Why, chancellor Rishi Sunak of course, hoping to step up to become PM on a Treasury-determined manifesto of immediate recession-inducing tax rises. That unprecedented shock of interest payments could almost have been designed to illustrate the Treasury's - sorry, Rishi's - argument. And probably was - 6.2SDs after all.

The UK is about to enter the strange and disturbing world of sustained double digit inflation. We can tell that from the underlying trends generating June's 9.4% yoy headline CPI, but also by the way the gap between input PPI (24% yoy) and output PPI (16.5% yoy), and the gap between output PPI and CPI are continuing to widen. Not until we see some evidence that the pressure to 'pass-through' factory inflation pressures has peaked can we expect headline CPI to retreat. There's no sign of that yet.

Fiscal policy is doing the heavy lifting as China seeks to re-start its economy following zero-Covid strategy lockdowns. June's monthly data suggests they're having some success in re-opening, even if this isn't obvious in the yoy results.

But 2Q GDP growth of 0.4% yoy catches China's economy at its lowest ebb, and the closer you look at it, the uglier it gets. After all, this 0.4% yoy growth was generated really only by net exports and a surging fiscal deficit - strip those out and 2Q nominal domestic demand was in freefall. Which is what you'd expect when you close down the economy.

Full all-singing, all-dancing illustrated & detailed version available on the Coldwater Economic sustack page.

People are queuing outside some small banks in Henan, desperate to rescue their deposits. Is this the start of another near-collapse of China's banking system.

On balance, the available evidence makes that very unlikely.

We've now had more of January's foreign reserves data for Asia, and its generally shown modest falls, as you'd expect when the dollar strengthens and asset prices fall. To recap: China's reserves fell 0.9% mom, Japan's fell 1.4% S Korea's fell 0.3% (thanks to some very active switching out of bonds);and Indonesia fell 2.5% (includes some foreign debt repayment). But Singapore managed a 0.1% rise.

Today we had Hong Kong, which reported reserves down 0.9% mom - ie pretty much in line with what we've seen elsewhere. But there are a couple of problems: first Jan's loss comes after a year of near stasis, with the result that reserves are now falling in yoy terms. This is only marginal, but its very rare for HK, and shows that HK has received negligible reserves inflow from global QE this time - in stark contrast to the reserves bonanza HK enjoyed in 2009/2010. The second problem is this: the HK dollar is run as a currency board: in theory, if foreign reserves fall, then the net HK$ clearing balance of the banking system, or currency in circulation, has to shrink too. In simple terms, the impact of falling foreign reserves is sharper in HK than in most Asian economies. And so, in Nov HK M0 grew only 1.7% yoy, and in Dec HK$M3 only 1.5%.

And there is this third consequence: Hong Kong's continuing liquidity is increasingly being supplied by China. We have the net international breakdown of HK's banks net int'l position only up to October. But what is shows is consistent with the rising pressure: HK banks' total net assets fell by US$51bn yoy to US$327bn; but its position with China fell $41bn to a net liability of $28bn. My bet is that by January it was much deeper. Again, having a net liability position to China is very rare for HK - back in 2014 it had net assets in China of $335bn. The last time it had a net liability position was back in . . . 2008 - 2009.

What this adds up to is HK's increased financial vulnerability to a) a strengthened dollar; b) any tightening in China; plus, of course, any feedback in loss of confidence. That's quite a lot of vulnerability to take into the likely environment of 2022.

There are statistics raw, and there are statistics adjusted. By and large, the more statistics are adjusted to give a 'clearer view', the more careful you've got to be about them.

With that in mind, I want to share some observations on Friday's US labour survey data. On the face of it they were extremely positive: non-farm payrolls were up 467k, and Dec's payrolls were revised up to 510k from an initial 199k. Even more spectacularly, Jan's h'hold survey of employment found employment up 1.199mn, which was the sharpest monthly gain since January 2000, on the back of an extraordinary 1.393mn rise in the labour force as the labour participation rate rose 0.3pps to 62.2%, the highest since March 2020.

Not only are these really dramatic gains, but they also run absolutely counter to what ADP found in its Jan survey of private employment, where payrolls fell by 310k.

What's going on? The thing you need to is that the strength of Jan's labour survey results is largely the result of statistical adjustment of truly monstrous proportions. The seasonally adjusted establishment survey of non-farm payrolls rose 467k mom, but the unadjusted number show a fall - yes, a fall - of 2.824mn mom. Similarly, the household survey's reported a seasonally adjusted 1.199mn rise in employment: but strip out the seasonal adjustments, and the raw numbers show a fall of 114k in January.

There are at least two different things going on here, quite apart from the 'normal' seasonal adjustment. The first is simply that the Bureau of Labor Stats has revised its seasonal adjustment process, notably taking into account the massive disruptions seen during the onset of the pandemic and subsequent recovery. This is responsible for the major upward revision in Dec's data, with the massive strength in June/July last year being quietly, and for these purposes invisibly, being revised down. This is what is behind the abnormal and anomalous seasonally adjusted strength in non-farm payrolls reported in January.

The impact of this change is going to be felt throughout the year: essentially it will bias non-farm payrolls results upwards through to May, before reversing the bias downwards sharply from June through to November. You've been warned.

The second concerns a big technical change in the h'hold survey - the once which produced a rise of 1.199mn in January's employment despite a non-adjusted fall of 114k. What's happening here is that Jan's survey introduced updated population estimates, with a new estimate of population from the 2020 census & later data, rather than the 2010-based data which was what was used for the Dec 2021 survey. That, and that alone, raised the estimate of the labour force in Jan by 1.53mn, raised employment by 1.47mn, and unemployment by 59k.

And you'll have spotted it: if the change in census base raised employment by 1.47mn, and Jan's survey reported a rise of only 1.199mn, what it is telling is is that on same-survey basis regardless of seasonal adjustment issues, h'hold employment actually fell by 272k.

To summarise: we're all going to have to take the monthly labour market surveys from the US with a very large pinch of salt for the coming year: the next few months are going to be great: after that, not so much.

I'd expected that inflation was coming back for a second bite in January, but Eurozone's Jan CPI was far worse than even I had expected. Headline CPI up 5.1% yoy, with a monthly rise 3.3SDs above historic trends. Energy alone was up 6% mom and 28.6% yoy, but in addition, F&B was up 1.1% mom and 3.6% yoy. Energy and food - even if energy prices calm down, food inflation will stay with us, thanks to the longer-term impact of the jump in fertilizer prices. Strip energy and food out, and core CPI was up 2.3% yoy, but with a monthly movt 2.3SDs above historic seasonal trends.

The big problem is that January was the month when the Eurozone base of comparison turned friendly: Jan 2021's monthly rise was no less than 4.1SDs above trend, mainly because of the sharp and encouraged rise in CO2 emission prices. So Jan 2022 ought to have offered relief. That it didn't means we've got to raise likely yoy rates for the rest of the year. The revision is sharp too, pushing the likely yoy up by around 1pp for the whole of the year. That means its now reasonable to expect 1Q CPI to average 5.3%, 2Q 5.8%, 3Q 5.9% and 4Q 5.2%. Core CPI, meanwhile, will can be expected to rise above 3% for most of the year, starting in March.

Meanwhile, yesterday 10yr yields were at 0.04%.

It's very hard to see how the ECB can keep the pedal to the metal when you've got this scale of inflation.

Over in the US, I follow heavy truck sales as a good leading indicator - at least for recession. January's sales were extremely encouraging : not only were Jan's sales up 13.1% mom to the highest monthly total since Sept 2019, but in addition, sales numbers were revised up very sharply - by 27% no less from what was initially claimed. A rebound on this scale over the last two months removes what had been a worrying recession signal.

By contrast, the 301k fall in Jan's ADP's private payrolls count looks, on the face of it, grim. But for the time being, I'm suspending judgement. Why? First, remember that in Dec we had a 776k rise. That was exceptionally strong, and the pullback in Jan still leaves jobs up 475k over the last two months - and that's a very strong number indeed, comparing with 273k averaged in this period over the last five years. Second, more than half the fall came from leisure and hospitality - down 154k, which is hardly surprising given that a) holiday season is over and b) omicron is with us.

Jan's inflation has regained some momentum, reversing the slight relief we got in Dec's results. We've now had Jan CPI flashes from both Germany and France, and they confirm it. Germany's CPI was up 4.9% yoy against a very steep base of comparison (because Jan 2021 was when German CO2 charges really escalated). The monthly rise of 0.4% mom is 2.2SDs above historic seasonal trends. Not only was energy up 20-.5% yoy, but food was also up 5%.

This year, food inflation is going to feature heavily around the world, in response to the jump in fertilizer costs in 2020.

France's CPI also rose 2.9% yoy, which was worse than expected, with a 0.3% mom rise which was 1.8SDs above what was expected. Like Germany: energy was up 19.7% yoy, and fresh food was up 3.6%.

Tomorrow we get the Eurozone CPI flash: at the moment, consensus is expecting 4.3% yoy, but from what we know now, it will come in a bit higher than that.

The second thing I want to draw your attention to is an addition I've made to my data universe. I've included the Chicago Fed's Brave-Butters-Kelley (BBK) set of coincident and leading indexes for the US for the first time. Data is something I take seriously, but it has a fundamental problem. In particular, the idea that there is an unaltered canon of measurements that make up 'the economic data' is misleading - because an economy is a thing that's changing all the time, and the things that get included as 'the data' can only ever reflect an economic structure that have already been and gone. That's the 'data problem'. One way to address that is to scan as widely as possible - it's why I look at 500 data pieces every month.

The BKK indexes do pretty much the same, taking into account 500 datastreams a month just on the US. This is almost a 'big data' view on the US economy, and one I very much approve of. In Dec the BBK coincident index was 0.66 SDs above trend (good); but the leading index was 0.31 from trend (bad). Interpreting that, it suggests GDP growth was running at an annualized 4.6% in Dec. But there are warnings here too: this running growth rate was down from the 8.3% signaled in Nov and 9.1% in Oct. Worse, the leading index has been consistently negative now since April last year, and during June-August came within a whisker of minus 1 each month.

The significance? Leading index readings below minus 1 tend to signal an elevated likelihood of recession ten months out: ie, between March and May this year. I think that 'biggish data' judgement is worth taking seriously.

Germany's Deficit Blowout

Today's most important surprise - or shock - came from Germany, whicc reported a federal budget deficit of Eu48.bn for December. That compares with a surplus of Eu2.9bn in December last year, so it's a massive turnaround. It's not because revenues are down, it's because spending is truly spiraling: revenues were up 35.3% yoy, with a monthly movt 2.4SDs above historic seasonal trends. But spending jumped 153% yoy, with the monthly movt a trend-shattering 5.1SDs above historic seasonal trends.

Germany's pandemic has had a different rhythm to the rest of the world, escaping the worst in the first half of 2020, only to be ambushed towards the end of November last year. As a result, Germany's fiscal deterioration in 2020 and most of 2021 was far less dramatic than elsewhere.

But that deterioration is with us now: in 4Q, the Eu82.25bn deficit was equivalent to 8.8% of quarterly GDP, taking the deficit for calendar 2021 to 6% of GDP (vs 3.9% in 2020).

What's more, it will widen further this year, not only because Germany's pandemic continues, but also because the new government has just passed a supplementary budget allowing them to spend unused loans worth Eu60bn, to be spent on investments in climate protection and digitization. Fiscal consolidation will have to wait until 2023.

This means that Germany's fiscal policy will be expanding hard at a time when all its major trading partners are busy taking taking back the extraordinary fiscal expansion seen in 2020. For example, in the UK, the 2021 net public sector borrowing of £183bn is down 30.4% yoy, in the US, the federal deficit narrowed by 23% in 2021; and in Japan the 2021 fiscal deficit narrowed 38.9%, and even in China, the deficit probably narrowed by around 25.5%

In addition, of course, whilst the ECB is necessarily committed to maintaining its expansionary policy with near-zero interest rates, central banks in other major economies are taking the first steps towards tightening.

Frankly, I don't remember another time when Germany and by extension Europe was committed to expansionary monetary and fiscal policies whilst all other major economies were retrenching. This is the reverse of the usual dynamic. Could it be that it's enough to de-synchronize world growth patterns in 2022, with Europe actually emerging as a net source of demand for the rest of the world? If so, it's a big departure from their traditional mercantilist model. What's more, although fx movements are in my view unforecastable, this policy contradiction between Germany and the rest of the world would seem to suggest stress on the Euro. But, please bear in mind, that's not a forecast, merely an observation.