Discover Vittles

Vittles

Vittles

Author: Vittles

Subscribed: 7Played: 95Subscribe

Share

© Vittles

Description

Vittles is an online magazine based in the UK and India, publishing new food and culture writing.

www.vittlesmagazine.com

www.vittlesmagazine.com

10 Episodes

Reverse

This month's episode covers the volatile world of public relations in restaurants. The industry has been grappling with this uneasy relationship between restaurants, journalists and PRs for as long as PR has existed. On the one hand, pioneering PRs like Alan and Elizabeth Crompton-Batt are partially responsible for the London restaurant scene as we know it today, helping to create the template for the celebrity chef that runs from Marco Pierre-White to The Bear. On the other, both restaurant owners and journalists have talked to us about their feelings of resentment about relying on PR, with some making it a matter of pride to never use or engage with it. Whatever your opinion, PR remains a significant and integral part of London’s restaurant scene. Almost every new restaurant hoping to get press uses PR... and it seems that the more they do, the more the rest of them need to as well.So it felt like the right time to invite a titan of the restaurant PR industry on this podcast. Gemma Bell is one of the most influential restaurant PRs in the country today, heading up her own agency Gemma Bell & Company, whose clients over the last 15 years have included St. JOHN, Dishoom, Yotam Ottolenghi, The River Café, Koya, Padella, The Clove Club and many more.Adam Coghlan has known Gemma for about 15 years and in that time, the industries of public relations and restaurants have changed dramatically, particularly due to the influence of social media. In this podcast we talk about those huge changes, about what clients want from PR, what she feels her role in the industry is, the influence of her mentors (including Elizabeth Crompton-Batt and hotelier Ian Schrager), parting ways with Yotam Ottolenghi and the biggest lesson she’s learnt from the last two to three decades of working in the restaurant world.We hope you enjoy it.CreditsThe Vittles Podcast is presented by Vittles Restaurants editor Adam Coghlan.Gemma Bell is the founder of the agency Gemma Bell & Company.Lucy Dearlove is an audio producer, sound designer and writer originally from North East England, now based in St Leonards-on-Sea. Her food podcast, Lecker, is a two-time winner of the Fortnum & Mason Podcast of the Year Award.The full Vittles masthead can be found here. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.vittlesmagazine.com/subscribe

This month’s episode is an interview with someone you might already know — a restaurant owner who embodies many of the critical themes of the London restaurant industry, not just in 2025, but over the course of the last 20-plus years: community, trends, family, uncertainty, hype and more. Ferhat Dirik is the lifelong front-of-house, founder’s son, and now owner of Dalston’s Mangal 2, the family-run Turkish restaurant he’s been working in since he was 11 in the late 1990s.Mangal 2 is one of the most well-known and cult-followed ocakbaşıs in north London. Opening in 1994, it was the follow-up restaurant to the U.K.’s first ocakbaşı (Mangal 1) which Ferhat’s father Ali Dirik opened 1991, and has been at the centre of that community ever since. Catering first to the Turkish community of Stoke Newington High street, then through the hipster era of Dalston in the 2010s, to serving Action Bronson, Dua Lipa, Charli XCX and so many others over the course of the last half decade. But during the course of the last 15 years and increasingly under the stewardship of Ferhat, the restaurant has gone from the community fringes of neighbourhood restaurant territory and into the mainstream. A fully fledged member of the London restaurant industry.So it felt like the right time, as the sun sets on another challenging year for London restaurants and in light of a series of illuminating blog posts authored by Ferhat in recent months, for Adam Coghlan to talk Ferhat about his journey, about the history of his family’s restaurant, what it means to serve people in London, about change, about speaking out, and about whether the end might well be nigh for one of the city’s most well-known and beloved places to eat.We hope you enjoy it.CreditsThe Vittles Podcast is presented by Vittles Restaurants editor Adam Coghlan.Ferhat Dirik is the owner of Mangal II in Dalston.Lucy Dearlove is an audio producer, sound designer and writer originally from North East England, now based in St Leonards-on-Sea. Her food podcast, Lecker, is a two-time winner of the Fortnum & Mason Podcast of the Year Award.The full Vittles masthead can be found here. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.vittlesmagazine.com/subscribe

We are living through an age of online extremes: hype machines, queues, hidden gems, while at the same time, for some of those embedded in the London restaurant industry itself, there’s a fundamental sense of malaise, of boredom, with a creeping homogenisation of restaurants and food culture. This is ‘the mid’: a term that is now common parlance for those who feel adrift of a discourse in which everything is either ‘absolutely incredible’ or ‘totally garbage’. In this month’s hour-long episode, we go deep into some of the forces shaping what we deem to be good, bad and, critically, mid in food right now, with not one, but two heavyweight London influencers: Feroz Gajia, food Instagram chief and chef-owner of Bake Street in Clapton, and Montague Ashley-Craig, author of the Everything’s Toasted newsletter and founder of luxury-small-plate-wine-bar-friendly soap brand, Montamonta. We discuss distinctions between London and other big cities in the world, the role of influencers, a recent New York Times list of 25 essential London restaurant dishes, delivery apps, PR and the subjectivity around ideas of quality. At the end, and in a bid to animate some of our theories, we debut the Vittles Podcast show-and-tell, as our host and guests reveal, eat and discuss a food stuff they feel represents the best of the middle ground.Like our previous two podcasts, this episode is free to listen to for all subscribers. You can listen to it here in Substack, or on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. If you’re so inclined, please like, share, rate and comment wherever you get your podcasts. A massive thanks as usual to Lucy Dearlove, our producer, and to the whole team at Young Space, the beautiful location where we record. We’ll see you again next month, when Adam will be speaking with Mangal 2 owner Ferhat Dirik. CreditsThe Vittles Podcast is presented by Vittles Restaurants editor Adam Coghlan. Montague Ashley-Craig is the creator of the ‘fancy restaurant handwash’, montamonta. She is also a Glaswegian, begrudging London Fields resident, cosmetic scientist, and annoying over-sharer with strong opinions loosely held.Feroz Gajia is the founder of Bake Street in London. Sometime food writer, Instagrammer and consultant, he is always obsessed with something, mostly food. He makes what you want to eat. Lucy Dearlove is an audio producer, sound designer and writer originally from North East England, now based in St Leonards-on-Sea. Her food podcast, Lecker, is a two-time winner of the Fortnum & Mason Podcast of the Year Award.The full Vittles masthead can be found here. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.vittlesmagazine.com/subscribe

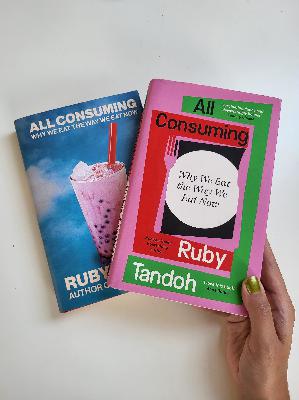

In this special episode, Adam Coghlan is joined by Ruby Tandoh, the author, journalist (and Vittles contributor) who has just published the book All Consuming: Why We Eat the Way We Eat Now. The book is an attempt to explain the growing power and absurdity of food culture via the mediums it is transmitted through, whether supermarkets, newspaper supplements or Instagram reels (Tandoh’s ‘15 Cookbooks That Changed Everything’ which was published on Vittles earlier this year was loosely based on chapter on cookbooks). As a sprint through the terrain of contemporary food culture, All Consuming covers everything from the rise of bubble tea, restaurant critics in the US and in the UK, food influencers, supermarket battles, the dominance of the queue, TikTok, wellness elixirs, trad wives, the invention of Viennetta and modern ice cream culture, Mob Kitchen, recipe development, and the impact America has had on British food (via Wimpy). We talk about the process of writing the book, the speed at which food culture is changing, and the democratisation (and regression) of food media. Later on in the podcast, Adam checks in with Vittles founder and editor Jonathan Nunn, who has some thoughts about the current state of fine dining, including reviews of Row on 5 in London, and Wilson’s and Upstairs at Landrace in the West Country. Like our previous two podcasts, this episode is free to listen to for all subscribers. You can listen to it here, or on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you normally listen to your podcasts. The Vittles Podcast will continue later this month with an episode in which we speak with two ~tastemakers~ about some of the undercurrents affecting the London restaurant industry and their own competing versions of what’s good and what’s… mid. A massive thanks as usual to Lucy Dearlove who produced it, and to the Young Space who provided the beautiful recording space.CreditsThe Vittles Podcast is presented by Vittles Restaurants editor Adam Coghlan. Ruby Tandoh is a writer and hater on food and culture whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Guardian, Vice, Taste, Eater, Vittles and more.Lucy Dearlove is an audio producer, sound designer and writer originally from North East England, now based in St Leonards-on-Sea. Her food podcast, Lecker, is a two-time winner of the Fortnum & Mason Podcast of the Year Award.The full Vittles masthead can be found here. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.vittlesmagazine.com/subscribe

In this month’s episode, we have a special guest: writer, critic and part-time Vittles reviewer Simran Hans, who joins Adam and Jonathan to talk about the summer in London restaurant news. Our main topics are two eccentric London food spaces: Singburi and Leila’s Shop. We discuss what didn’t make into Jonathan’s review of Singburi, our thoughts on the new one, and what the restaurant’s evolution says about the state of the London industry more generally. We also talk about Leila’s Shop and its current fight for survival on Calvert Avenue in the context of Simran’s March review, It’s Time to Talk About Leila’s (the alternate name for this episode was ‘I would just like to state for the record that I have signed the petition’). Plus! Stupid summer beverages, what we’ve enjoyed and not enjoyed in London restaurants this year, and a short look back at five years of Vittles.Like our previous special podcast on The Lost Food of Soho, this episode is free to listen to for all subscribers. You can listen to it here, or on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you normally listen to your podcasts. A massive thanks as usual to Lucy Dearlove who produced it, and to the Young Space who provided the beautiful recording space.CreditsThe Vittles Podcast is presented by Adam Coghlan. Simran Hans is a writer in London. Her work has been published in the New York Times, the Guardian, the Observer, the Financial Times, GQ, VICE and many others. You can read some of it at simranhans.com or find her on Instagram @simranhans.Lucy Dearlove is an audio producer, sound designer and writer originally from North East England, now based in St Leonards-on-Sea. Her food podcast, Lecker, is a two-time winner of the Fortnum & Mason Podcast of the Year Award.The full Vittles masthead can be found here. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.vittlesmagazine.com/subscribe

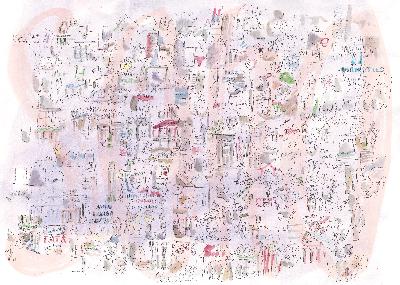

The Lost Food of Soho is a one-episode podcast by Lucy Dearlove. You can listen to it for free on Substack, on Apple Podcasts or Spotify, which are now hosting all back-issues of the Vittles podcast. You can buy prints of today’s map, created by the artists Anna Hodgson and Harry Darby exclusively for Vittles. A reminder, too, that we’ve released prints ahead of the publication of issue 1 of Vittles magazine, which you can shop here.Cast of The Lost Food of SohoHilary Armstrong – writer, worked in Andrew Edmunds Marcus Harris – DJ/promoterRussell Davies – creator of eggbaconchipsandbeansJeremy Lee – chef proprietor of Quo VadisChristine Yau – former owner of Y MingDarren Coffield – artist and author of Tales From The Colony Room: Soho’s Lost BohemiaIain Sinclair – authorPolly – sex work and organiser with SWARMMegan Macedo – writer and former Sister Ray employeeThere are many versions of Soho. ‘Italian caffs and delis Soho’. ‘Private members club Soho’. ‘Jazz bar Soho’. ‘Blitz Club Soho’. ‘Terence Conran Soho’. ‘Film industry Soho’. ‘Music industry Soho’. ‘Paul Raymond Soho’. All existing separately but simultaneously: sometimes overlapping, sometimes built on the rubble of each other.We often talk about an ‘Old Soho’ of the mind – sometimes entirely of the imagination. Usually the qualification for a person or an establishment being worthy of the description ‘Old Soho’ is for it to be no longer with us, but there are some exceptions: Trisha’s, Bruno’s, The Admiral Duncan, Ronnie Scott’s, Algerian Coffee Stores, Bar Italia, Andrew Edmunds. Then there is a ‘New Soho’, mainly made up of restaurants. These two places, taking up the same physical space, are often pitted against each other, but I have little nostalgia for Old Soho. As the historian Dan Cruickshank puts it in his book Soho: A Street Guide to Soho's History, Architecture and People: ‘from the debris of death and destruction has sprung new life, often strange and exotic.’But even allowing for nostalgia, you can’t avoid that Soho has experienced huge, irredeemable losses. Many of them restaurants. Many of them since 2000. The Stockpot, Alastair Little, Ed’s Easy Diner, Dionysus, the New Piccadilly, Y Ming. Then there are the many unheralded takeaways and late night restaurants serving the area around Tottenham Court Road, Oxford Street and the northern streets of Soho during the early 2000s before various factors, Crossrail included, physically decimated the night time economy. These are the places I want to celebrate in The Lost Food of Soho. Soho is constantly shifting and evolving, and I wanted to draw a line in the sand for the period during the 2000s in which I got to know it, which often feels overlooked. ‘My’ Soho now feels like it qualifies as Old Soho too. Millennial Soho — just like its patrons — had one foot in the past and one eye on the future, whether it liked it or not. In a strange way, it has changed the way Londoners eat. Lucy DearlovePlaces named in The Lost Food of Soho, in order of mention:Dionysus, The Astoria, The French House, Metro Cinema, The Palomar, Burger King, The Stockpot, Ed’s Easy Diner, Wimpy, Presto, Zed Cafe, Burger and Beyond, Patty and Bun, The Breakfast Club, Cheat Meals, The Admiral Duncan, Comptons, Joe and the Juice, Andrew Edmunds, Maison Berteaux, Patisserie Valerie, Quo Vadis, Bifulco, Debono, I Camisa, Cheung Dam, Y Ming, Bar Italia, Ronnie Scott’s, Garlic and Shots, Alastair Little, Koya, Hoppers, Ciccone’s Pizza Bar, Wheeler’s, The Colony Room, Duck Soup, Bar Pollo, Soho House, Zilli’s, Cafe Boheme, The Gay Hussar, Bob Bob Ricard, Pizza Express, Sister Ray, Vital Ingredient, Tossed, Soderbergh, The Blue Posts, Berwick Street Market, Pizza Pilgrims, Bone Daddy, Supreme, Bar Bruno, The Intrepid Fox, Byron, Madame Jojos, Raymond Revue Bar, The Box, Rooms by the Hour, The New Piccadilly, The Devonshire. CreditsLucy Dearlove is an audio producer, sound designer and writer originally from North East England, now based in St. Leonards-on-Sea. Her food podcast, Lecker, is a two-time winner of the Fortnum & Mason Podcast of the Year Award. The full Vittles masthead can be found here. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.vittlesmagazine.com/subscribe

This is a free preview of a paid episode. To hear more, visit www.vittlesmagazine.comVittles Quarterly: The Peasant Food RemontadaGood morning and welcome back to our series of quarterly conversations between Vittles Restaurants editors, Adam Coghlan and Jonathan Nunn. You can find the first episode here and the second episode here.On this episode, for our end of year review, we’re joined by Hester van He…

This is a free preview of a paid episode. To hear more, visit www.vittlesmagazine.comGood morning and welcome to the second in a series of quarterly conversations between Vittles Restaurants editors, Adam Coghlan and Jonathan Nunn. You can find the first episode here. This month we discuss the biggest story in food media in 2024 - the resignation of Pete Wells from the most powerful job in restaurant criticism for health reasons - and h…

This is a free preview of a paid episode. To hear more, visit www.vittlesmagazine.comGood morning and welcome to the first in a new series of quarterly conversations between Vittles Restaurants editors, Adam Coghlan and Jonathan Nunn. Every three months or so we’re going to talk about what and where we’ve been eating, the best meals we’ve enjoyed, things that are annoying us, exciting us, and what we’ve observed in the London restaurant…

Good morning and welcome to this special edition of Vittles. Normally Friday articles are paywalled, but I have dropped the paywall for today because I would like this conversation to be widely read, especially by people in Bristol.The following article is an abridged transcript of a conversation between five people involved in the Bristol food and media scene ─ Fozia Ismail, Jan Ostle, Aine Morris, Khalil Abdi and Holly Nash ─ taking off from an article published last year in Vittles. If you wish to listen to the whole thing, then the podcast is embedded in the article. All contributors are paid for their time, so if you can, please do consider subscribing through Patreon.About a year ago, I received a pitch from the journalist Holly Nash who wanted to write an article about the Bristol Food Union (BFU), which had recently formed. I commissioned it, first of all because I was interested in how restaurants were changing to adapt to the pandemic conditions and there seemed to be a hopefulness that business models could be permanently shifted to take a wider community into account. I was also interested on a personal level, that I seemed to know more about the food ecosystem of New York or Los Angeles more than I did Bristol, so dominant is the London narrative in food writing. A few weeks later, not too long after a Guardian article which promoted the community work of four pandemic success stories, including the BFU, Holly returned to me saying that the issue was more complex than she had initially anticipated. Although the BFU was undeniably doing good work, there were many more organisations doing community work that needed promoting, as well as a feeling of insider/outsider-ism in terms of who gets media coverage. After chatting to her about it, we agreed on a new direction, and I also put her in touch with the chef and writer Fozia Ismail, who was able to confirm these ambiguities and also put Holly in touch with more chefs and activists. All in all, the article took around four months to publish and was, at that point, the longest I’ve ever had an article in edits.Holly’s article remains one of the things I’m most proud of publishing at Vittles. When it got published, the response from people who lived in Bristol was overwhelmingly positive ─ that it was one of the first times they had seen Bristol food culture be accurately portrayed in a non-local publication, but also that it did not shy away from the truth that there is an elitism and hierarchy in what the media usually choose to portray. Another reason I’m proud of it is because it was taken in the way it was meant to be taken ─ as a piece of constructive critique rather than a takedown. I think many people could have ignored it, or shut down any criticism, but Aine Morris, who is one of the BFU’s founders, engaged with the hard questions that the piece asked.It is because of Aine, who proposed this talk, as well as Fozia and Holly, that we are having this conversation today. Over the past few months I have been reflecting on food community projects ─ having talked to other people in charge of community work and seeing how it plays out in my own community ─ and how complex the subject is. No one article can capture the logistics involved, as well as the trade-offs every organiser has to make: whether to get corporate sponsorship, how to marshall the media to grab attention, whether to stay small and local or to increase your reach and spread yourself thinner. Larger projects can overshadow smaller ones, but it’s also true that they can also be responsible for funding or supplying food to them ─ as Bristol Food Union does.The aim of today’s discussion is to look as those complexities, and unpick the areas of commonality and the areas of friction, and look at how collaboration between sectors is possible, and indeed, where there have already been collaborations. In addition to Fozia ─ who will be leading today’s conversation ─ Holly and Aine, we also have Jan Ostle from the acclaimed restaurant Wilsons and Khalil Abdi from Bristol Horn Youth Concern. Over to Fozia!Fozia: Thank you all for being here! I’m just going to kick it off with some of the themes we want to talk about. The article caused controversy at the time but we really wanted to explore what is it about the Bristol food scene that is unique compared to London. Bristol does get a lot of food media attention in some respects, but there is a lot that is also ignored by the media. So we’d love to get your opinion on what you think characterises the Bristol food scene? Aine shall we start with you?Aine: Thank you, both. Holly for writing the original article, and Fozia and Jonathan for creating the space to be able to continue the conversation. I think I came to you after the article because it felt like there was more to be said, both around the challenges, but also the potential here in Bristol to deliver something that is genuinely unique and more inclusive than food communities in other cities. How would we characterise the Bristol food scene? In and of itself, that’s quite a challenging question. Because what’s come out, not in the article, but instigated by the article is this period of collective thinking. It’s clear that while we have a thriving food community here, one which is genuinely committed to change and food access at every level of society, we also have quite a silo-ised food movement. Not just silos in terms of celebrity or Michelin starred chefs vs community food projects, but we have a very white, middle class, farmers market and food sustainability movement here, we have a very active food access and food waste charity sector here, which can be separate from the fine dining and food media collective. I would characterise what already exists here, and I would say it carefully, as having lots of potential, but not being particularly joined up in the way we think it is, or in the way it comes across in media articles to people who don’t live here.Khalil: Thank you for organising this, I really appreciate it. It’s the first time we have been involved in something like this. To answer the question: Bristol has been dominated by white led food banks, which don’t want to engage in the community. We don’t have that much connection. There’s a lack of communication and lack of connection with them, because they know people, they’re well connected, and they dominate because they know each other. They have links and they have more opportunities than us. When they come into the community, they don’t give us culturally appropriate food: people wanting Halal food for instance, or people who come from Africa wanting to see African food. There’s a lack of language ─ people give tins of meat that are not Halal which people don’t understand. And that’s why people don’t accept the food, because they don’t know what’s in it. Most of the people who work in food banks are white, they have no connection to the community, they don’t speak the language. That’s how it is in Bristol. It’s segregated when it comes to food. They often don’t want you to be involved; they never invite you to the meetings, or if they have an event. In terms of media, they only want to interview you if there’s something negative. When you’re doing something positive, they don’t want to promote it. That’s the culture in Bristol. We’ve seen many times when there’s something negative, all the media come, but not when there’s something positive.“That’s how it is in Bristol. It’s segregated when it comes to food.”Fozia: That’s a really interesting point Khalil. You’re talking about the wider system of accessing, I guess, funding, and also those networks about who gets to access these networks in the Bristol space. Not just funding but media attention. I’ve seen a lot of grassroots mutual aid groups being set up by BAME groups, and that’s amazing to see on the ground. It is interesting that this doesn’t get spoken about in the same way.Khalil: Other big food banks or charities don’t want to entrust things to you, or want you to be seen as a success. They don’t want to give you a platform. They have the power, they have the connections, they have a system where they can access more information than you. They always shut you down and change the subject if you manage to get a little bit up the ladder, and the next time you won’t get an invitation, especially if you speak up about how you feel about it. Other people tell you “oh the meeting is still happening, we haven’t seen you?”. But that’s how it works.Fozia: Holly you interviewed a few other organisations working in this space, do you think what Khalil says is reflected in the work you did last year on this article?Holly: Yeah, what was just spoken about, definitely. I think the intention is always there in Bristol to have this really cohesive food scene but I think, there’s not an awareness of the disparity. I mean, I found out so much just from writing that piece, and stuff I was so ignorant of, so I’m a case for the point. Fozia: Going forward, how can we think about what can be done differently in our local and national media representation? Aine: I don’t want to speak for Jan, but both of us have been quite conscious about coming to this conversation with bringing our listening. Part of what I found challenging about Holly’s article personally, was that the BFU came across as the establishment, and I don’t see us as the establishment, or that we represent only a group of white, middle-class, Michelin starred restaurants. There is a problem with Michelin-starred chefs behaving like superheroes and going into communities and saying “don’t worry everyone, we’re going to cook for you now”, but it didn’t feel like that’s what we were doing in Bristol. Because, yes, we were working with kitchens to produce food, but we were supplying those meals directly into the Community Kitchen that featured in the article, or Baraka Community café, which featured in the article. We were wo