Bristol is not a melting pot, part 2

Description

Good morning and welcome to this special edition of Vittles. Normally Friday articles are paywalled, but I have dropped the paywall for today because I would like this conversation to be widely read, especially by people in Bristol.

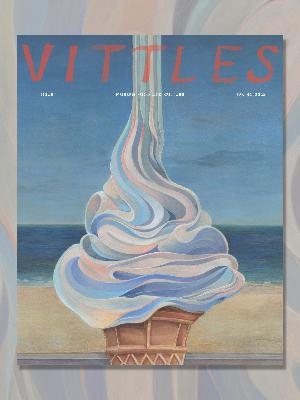

The following article is an abridged transcript of a conversation between five people involved in the Bristol food and media scene ─ Fozia Ismail, Jan Ostle, Aine Morris, Khalil Abdi and Holly Nash ─ taking off from an article published last year in Vittles. If you wish to listen to the whole thing, then the podcast is embedded in the article. All contributors are paid for their time, so if you can, please do consider subscribing through Patreon.

About a year ago, I received a pitch from the journalist Holly Nash who wanted to write an article about the Bristol Food Union (BFU), which had recently formed. I commissioned it, first of all because I was interested in how restaurants were changing to adapt to the pandemic conditions and there seemed to be a hopefulness that business models could be permanently shifted to take a wider community into account. I was also interested on a personal level, that I seemed to know more about the food ecosystem of New York or Los Angeles more than I did Bristol, so dominant is the London narrative in food writing.

A few weeks later, not too long after a Guardian article which promoted the community work of four pandemic success stories, including the BFU, Holly returned to me saying that the issue was more complex than she had initially anticipated. Although the BFU was undeniably doing good work, there were many more organisations doing community work that needed promoting, as well as a feeling of insider/outsider-ism in terms of who gets media coverage. After chatting to her about it, we agreed on a new direction, and I also put her in touch with the chef and writer Fozia Ismail, who was able to confirm these ambiguities and also put Holly in touch with more chefs and activists. All in all, the article took around four months to publish and was, at that point, the longest I’ve ever had an article in edits.

Holly’s article remains one of the things I’m most proud of publishing at Vittles. When it got published, the response from people who lived in Bristol was overwhelmingly positive ─ that it was one of the first times they had seen Bristol food culture be accurately portrayed in a non-local publication, but also that it did not shy away from the truth that there is an elitism and hierarchy in what the media usually choose to portray. Another reason I’m proud of it is because it was taken in the way it was meant to be taken ─ as a piece of constructive critique rather than a takedown. I think many people could have ignored it, or shut down any criticism, but Aine Morris, who is one of the BFU’s founders, engaged with the hard questions that the piece asked.

It is because of Aine, who proposed this talk, as well as Fozia and Holly, that we are having this conversation today. Over the past few months I have been reflecting on food community projects ─ having talked to other people in charge of community work and seeing how it plays out in my own community ─ and how complex the subject is. No one article can capture the logistics involved, as well as the trade-offs every organiser has to make: whether to get corporate sponsorship, how to marshall the media to grab attention, whether to stay small and local or to increase your reach and spread yourself thinner. Larger projects can overshadow smaller ones, but it’s also true that they can also be responsible for funding or supplying food to them ─ as Bristol Food Union does.

The aim of today’s discussion is to look as those complexities, and unpick the areas of commonality and the areas of friction, and look at how collaboration between sectors is possible, and indeed, where there have already been collaborations. In addition to Fozia ─ who will be leading today’s conversation ─ Holly and Aine, we also have Jan Ostle from the acclaimed restaurant Wilsons and Khalil Abdi from Bristol Horn Youth Concern. Over to Fozia!

Fozia: Thank you all for being here! I’m just going to kick it off with some of the themes we want to talk about. The article caused controversy at the time but we really wanted to explore what is it about the Bristol food scene that is unique compared to London. Bristol does get a lot of food media attention in some respects, but there is a lot that is also ignored by the media. So we’d love to get your opinion on what you think characterises the Bristol food scene? Aine shall we start with you?

Aine: Thank you, both. Holly for writing the original article, and Fozia and Jonathan for creating the space to be able to continue the conversation. I think I came to you after the article because it felt like there was more to be said, both around the challenges, but also the potential here in Bristol to deliver something that is genuinely unique and more inclusive than food communities in other cities.

How would we characterise the Bristol food scene? In and of itself, that’s quite a challenging question. Because what’s come out, not in the article, but instigated by the article is this period of collective thinking. It’s clear that while we have a thriving food community here, one which is genuinely committed to change and food access at every level of society, we also have quite a silo-ised food movement. Not just silos in terms of celebrity or Michelin starred chefs vs community food projects, but we have a very white, middle class, farmers market and food sustainability movement here, we have a very active food access and food waste charity sector here, which can be separate from the fine dining and food media collective. I would characterise what already exists here, and I would say it carefully, as having lots of potential, but not being particularly joined up in the way we think it is, or in the way it comes across in media articles to people who don’t live here.

Khalil: Thank you for organising this, I really appreciate it. It’s the first time we have been involved in something like this. To answer the question: Bristol has been dominated by white led food banks, which don’t want to engage in the community. We don’t have that much connection. There’s a lack of communication and lack of connection with them, because they know people, they’re well connected, and they dominate because they know each other. They have links and they have more opportunities than us. When they come into the community, they don’t give us culturally appropriate food: people wanting Halal food for instance, or people who come from Africa wanting to see African food. There’s a lack of language ─ people give tins of meat that are not Halal which people don’t understand. And that’s why people don’t accept the food, because they don’t know what’s in it. Most of the people who work in food banks are white, they have no connection to the community, they don’t speak the language.

That’s how it is in Bristol. It’s segregated when it comes to food. They often don’t want you to be involved; they never invite you to the meetings, or if they have an event. In terms of media, they only want to interview you if there’s something negative. When you’re doing something positive, they don’t want to promote it. That’s the culture in Bristol. We’ve seen many times when there’s something negative, all the media come, but not when there’s something positive.

“That’s how it is in Bristol. It’s segregated when it comes to food.”

Fozia: That’s a really interesting point Khalil. You’re talking about the wider system of accessing, I guess, funding, and also those networks about who gets to access these networks in the Bristol space. Not just funding but media attention. I’ve seen a lot of grassroots mutual aid groups being set up by BAME groups, and that’s amazing to see on the ground. It is interesting that this doesn’t get spoken about in the same way.

Khalil: Other big food banks or charities don’t want to entrust things to you, or want you to be seen as a success. They don’t want to give you a platform. They have the power, they have the connections, they have a system where they can access more information than you. They always shut you down and change the subject if you manage to get a little bit up the ladder, and the next time you won’t get an invitation, especially if you speak up about how you feel about it. Other people tell you “oh the meeting is still happening, we haven’t seen you?”. But that’s how it works.

Fozia: Holly you interviewed a few other organisations working in this space, do you think what Khalil says is reflected in the work you did last year on this article?

Holly: Yeah, what was just spoken about, definitely. I think the intention is always there in Bristol to have this really cohesive food scene but I think, there’s not an awareness of the disparity. I mean, I found out so much just f